Summary

Adipose tissue dysfunction is typically seen in metabolic diseases, particularly obesity and diabetes. White adipocytes store fat while brown adipocyte dissipates it via thermogenesis. In addition, beige adipocytes develop in white fat depots in response to stimulation of β-adrenergic pathways. It appears that the three types of adipocytes – white, brown and beige – can be formed de novo from stem/precursor cells or via transdifferentiation. Identifying the presumptive progenitors that harbor capacity to differentiate to these distinct adipocyte cell types will enable their functional characterization. Moreover the presence or absence of white/brown/beige adipocytes is correlated with metabolic dysfunction making their study of medical relevance. Robust, reliable and reproducible methods of identification and isolation of adipocyte progenitors will stimulate further detailed understanding of white, brown and beige adipogenesis.

Keywords: Obesity, adipose tissue, WAT, BAT, beige adipose, stem cells, progenitor cells, ADSCs, flow cytometry

1. Introduction

Adipose tissue dysfunction, along with insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell failure, are at the core of the obesity and diabetes epidemic (1-3). White adipose tissue (WAT) depots are dispersed in distinct locations and serve the prime function of fat storage. In contrast, brown adipose tissue (BAT), typically localized to the supraclavicular and neck regions and along the spine, dissipates fat via a process termed as thermogenesis (4), driven primarily by the inner mitochondrial membrane protein Ucp1. Recent findings that metabolically active brown adipose tissue (BAT) exists in adult humans (5,6), has renewed widespread interest in its therapeutic potential to combat metabolic diseases (7,8). In addition to the classical BAT, adipocytes expressing variable levels of Ucp1 - termed beige or brite adipocytes - appear in white fat depots in response to cold exposure or upon stimulation by β–adrenergic pathways (9,10).

A summarization of several excellent studies suggests that brown and beige adipocytes may have a distinct developmental origin (11,12) with evidence favoring the existence of specialized progenitors that drive their genesis (13-15). In addition to de novo adipogenesis, a role for trans-differentiation has been proposed as a mechanism underlying beige/brite adipogenesis (16). Further, a bi-potential progenitor that differentiates towards white or brown adipocytes has been identified (17). Notably, Sca-1+/CD45−/Mac1− cells (14) and PDGFRα+/CD34+/Sca-1+ cells (17) have been suggested to have brown adipogenic potential, although it is unclear if these presumptive progenitors also promote beige adipocyte differentiation. Wang et al showed that the rate of white adipogenesis in both epididymal and subcutaneous adipose tissue varies with diet. Early exposure to HFD leads to adipose tissue expansion because of hypertrophy of adipocytes whereas more chronic exposure to HFD results in extensive adipogenesis of gonadal fat tissue, but not subcutaneous adipose tissue (15). With lineage tracking experimentation, Wang et al demonstrated that most of the newly emerging beige adipocytes in subcutaneous depots were not derived from preexisting white adipocytes, thus suggestive of a potential precursor cell that undergoes differentiation (15). Wu et al demonstrated that a subset of precursor cells within subcutaneous adipose tissue can give rise to beige cells, which are capable of expressing abundant UCP1 and a broad gene expression program that is distinct from either white or classical brown adipocytes. These inducible beige progenitor cells were sorted by flow cytometry based on expression of beige-selective cell surface proteins CD137 or TMEM26 (13).

Taken together, these data define a population of tissue resident, inducible beige/brown-adipocyte progenitors in mice. Understanding beige/brown adipogenesis, given that the appearance of these cells is associated with improved metabolism in mice (3,18,19), is thus of potential clinical relevance for metabolic diseases. Particularly, reliable and reproducible methods to identify, isolate and characterize presumptive progenitors that retain capacity to differentiate to the three adipocyte lineages – white, brown and beige – are important to further our understanding of their biology and functionality.

2. Materials

2.1. Tissue

Adipose tissue from several depots can be used to isolate ADSCs. We used epididymal/gonadal adipose tissue depot.

2.2. Supplies

Beakers

Mincing scissors

Scalpel

CO2

50 ml conical tubes

15 ml conical tubes

1 ml microfuge tubes

100 um mesh filter

5 ml round-bottom tubes for FACS

2.5 cm cell culture dishes

Hemocytometer

CO2 gas chamber

Water bath with shaker

Benchtop Centrifuge

Biosafety/Cell Culture hood

Vacuum filtration assembly

Microscope

CO2 incubator

2.3. Buffers and Culturing Media

-

Adipose tissue digestion buffer(a)

NaCl (123 mM)

KCl (5mM)

CaCl2 (1.3mM)

Glucose (5mM)

Hepes (100mM)

BSA (4%)

Collagenase I (1mg/ml)

Water to 50 ml

Collagenase solution: Weigh out 0.1 g of type I collagenase and dissolve it in 1 ml adipocyte isolation buffer. This solution can be stored for longer period at −20°C.

-

FACS Buffer

PBS with Mg++ and Ca++ (1X)

EDTA (1mM)

Hepes (25 mM)

Fatty Acid Free BSA (1%)

Dissolve bovine serum albumin (fraction V), EDTA and HEPES in 500 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After sterile filtration, warm the solution to 37 °C. This solution should be used within 1 h of its preparation.

Culture media: To 500 mL of DMEM media, add 110 mL of fetal bovine serum (20%) and 5.6 mL of antibiotic (penicillin/streptomycin)/antimycotic 100 × stock solutions. All the media solutions are filtered through a 0.2-μm filter unit.

2.4. Antibodies

CD31, 1:100, (Fluroschrome BV421)

CD34, 1:100, (Fluroschrome Pe-Cy5)

CD45, 1:100, (Fluroschrome APC-Cy7)

CD146, 1:100, (Fluroschrome PerCP-Cy5.5)

CD90, 1:100, (Flurochrome PE)

CD105, 1:100, (Flurochrome AF 647)

Live/Dead Aqua Antibody, 1:500

3. Methods

3.1. Adipose tissue depot excision and preparation

Euthanize mice with CO2 exposure at the rate of 3 L/min. Continue CO2 until one minute after breathing stops. Confirm euthanasia by performing cervical dislocation.

Immerse the whole mouse in 70% ethanol for 2-3 minutes followed by wash in PBS.

Pin the mouse to the dissecting surface. Open the mouse and remove the epididymal/gonadal adipose tissue depot. Make sure not to mix the adipose tissue from different depots if investigating depot specific differences.

Collect adipose tissue in 50 ml conical tube containing adipose tissue digestion buffer. If you are extracting adipose tissues from multiple mice then keep tube on ice until you are ready to mince the tissue.

Start with 5 ml per fat pad digestion buffer for lean mice and 10 mL per fat pad for obese mice.

Mince tissue into small pieces in up to 9 ml (1ml/0.1g tissue) supplemented digestion buffer

Use scissor to mince the tissue in fine pieces. It usually takes 2-3 min to mince adipose tissue to < 1mm pieces.

3.2. Digestion and incubation

Vortex tube containing buffer with finely minced pieces of adipose tissue and incubate at 37°C in water bath with shaker speed @220-250 RPM for 45-60 min

Vortex the tube every 10 min and make sure tissue pieces do not stick to wall of tube

Separation of adipocyte and stromal vascular fractions

After complete digestion, samples are poured onto a 100 μm nylon mesh into a new 50 ml tube to remove non-cellular fibrous material and undigested tissue. Rinse the filter with ~5 ml of supplemented digestion buffer

Spin the filtrate at 250 g for 5 min.

Remove the floating adipocyte layer (put on dry ice ASAP if using for RNA/protein) and most of supernatant with a (transfer) pipet into a new 15 ml tube and spin again. Collect the 1st pellet as the stromal vascular cell fraction (SVF).

3.3. Purification and preparation of SVF for FACS

SVF portion from the last step consist of several types of cells such as monocytes, lymphocytes, RBCs and others. To eliminate red blood cells use ACK lysis buffer.

Incubate the SVF with 0.5 or 1.0 ml of ACK lysis buffer for 1 min at room temperature.

Wash the pellet with 5 ml of FACS buffer and spin at 500 g for 10 min.

Centrifuge at 500xg for 5 min and re-suspend pellet in chilled sorting buffer to a concentration of 106 cells/100μl.

Freeze extra SVCs for RNA/protein extraction according to your experimental needs @ −80°C.

3.4. Staining and sorting

Get 2 Ice buckets and foil to keep cells from light exposure.

Re-suspend cells @ 1 million/100 uL in cold sorting buffer.

Refer to the for antibody dilutions info above. Add the antibodies one by one to the FACS buffer containing pellet. Mix well by pipetting. Incubate on ice for 30-45 min. Stained samples are washed twice and later sorted on FACSAria sorter (BD Biosciences, USA) equipped with 407, 488, 532, and 633 LASER lines using DIVA v6.1.3 software.

3.5. Gating and selection strategy for sorting

Populations are identified and sorted as per the gating strategy desired. This can be modified to what is needed per the experimental need. Briefly, after excluding cellular debris using a forward light scatter/side scatter plot, viable CD45 negative gate was determined based upon CD45 antigen staining properties. Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) can be sorted as CD45− CD31− CD105+ viable cells, whereas adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) sorted as CD45-CD31− CD105− CD34+ CD90.2+ cells. Furthermore, CD45− CD31+ CD34+ CD146+ cells are sorted as endothelial progenitors.

3.6. Collection and processing of ADSCs

Sorted cells are collected in DMEM media with 20% FBS. Cells are spun at 100 G for 5 min and washed once with the same media.

Cells are either plated on small diameter cell culture plate or collected for RNA or protein isolation.

ADSCs can subsequently be differentiated to either white or brown adipocytes using established protocols described elsewhere.

4. Notes

To maintain the sterile conditions during cell culture, frequent spraying of surface area and hands with ethanol is suggested. After euthanasia, mice carcass should be immersed completely in 70% ethanol for few minutes before opening up to collect adipose tissue.

Adipose tissue harvesting should be completed in a quick timeframe and SVC isolation should be initiated within 20-30 min of sacrifice while tissue sitting on ice during waiting period.

Because of their proximity to one another care needs to be taken to prevent mixing different adipose tissue depots during excision and isolation of cells.

Stock solutions can be prepared ahead of time, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C or −20°C for longer duration. Filter at the time of media preparation. Some filter materials may be sensitive to specific solvents (e.g., DMSO, methanol) and may disintegrate upon exposure; therefore it is safer to filter stock solutions after they are diluted in the medium.

After digestion, adipose tissue can be filtered to remove any remaining undigested pieces. Use a 100-μm filter (BD–Falcon) for filtering small volumes. However, to collect mature adipocytes at a later step, use a nylon filter (sterile) screen with a pore size of 250 μm.

In case pieces of undigested tissue in the sample remain after the 1 hour digestion, verify that the collagenase solution used is fresh and has not been maintained at room temperature for an extended period of time. This is important to maximize the enzyme efficiency. The collagenase solution can also be stored at −20°C for a few days, with a minor loss of enzyme activity. Prior to use, the frozen solution can be slowly thawed at room temperature and warmed to 37°C.

To accelerate cell adhesion, the culture dishes can be precoated with extracellular matrix components, such as gelatin or Matrigel.

High FBS containing media is recommended during initial stages of cell culture.

All animal procedures must conform to the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act and be approved before implementation by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

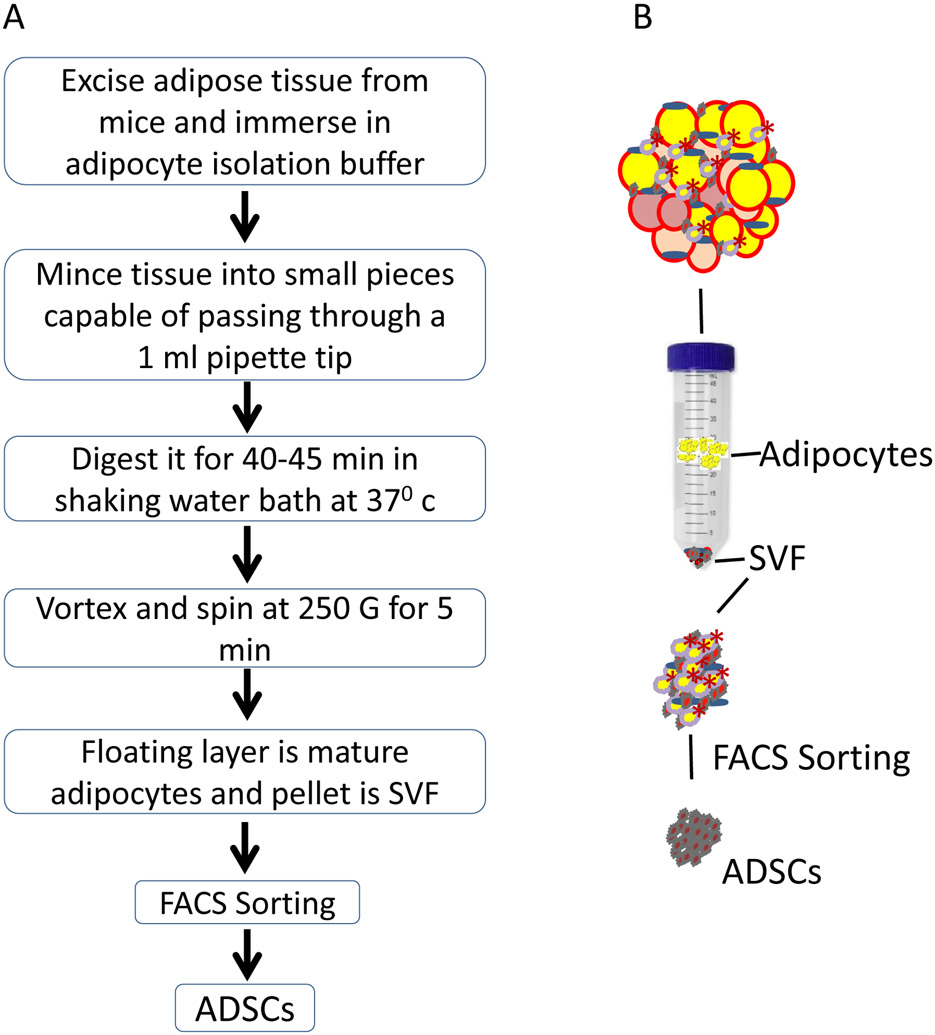

Fig. 1.

(a) Step by step flow chart of protocol, (b) Schematic representation of protocol

Table 1-.

Antibodies used for FACS sorting

| Markers | Adipose Derived Stem Cells |

Endothelial Progenitors |

Vascular Smooth Muscle cells /Pericytes |

Dilution | Fluorochrome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD31 | − | + | − | 1:100 | BV421 (BD) |

| CD34 | + | + | + | 1:100 | Pe-Cy5 (BioLegend) |

| CD45 | − | − | − | 1:100 | APC-Cy7 (BD) |

| CD146 | − | + | + | 1:100 | PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD) |

| CD90 | + | + | + | 1:100 | PE (BD) |

| CD105 | − | − | + | 1:100 | AF 647 (BD) |

| − | − | − | − | 1:500 | Live/Dead Aqua (Invitrogen) |

5. References

- 1.Sun K, Kusminski CM, and Scherer PE (2011) The Journal of clinical investigation 121, 2094–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gesta S, Tseng YH, and Kahn CR (2007) Cell 131, 242–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen ED, and Spiegelman BM (2014) Cell 156, 20–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon B, and Nedergaard J (2004) Physiological reviews 84, 277–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, and Cannon B (2007) American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism 293, E444–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, Kolodny GM, and Kahn CR (2009) The New England journal of medicine 360, 1509–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nedergaard J, and Cannon B (2010) Cell metabolism 11, 268–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enerback S (2010) Cell metabolism 11, 248–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cousin B, Cinti S, Morroni M, Raimbault S, Ricquier D, Penicaud L, and Casteilla L (1992) Journal of cell science 103 ( Pt 4), 931–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerra C, Koza RA, Yamashita H, Walsh K, and Kozak LP (1998) The Journal of clinical investigation 102, 412–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xue B, Rim JS, Hogan JC, Coulter AA, Koza RA, and Kozak LP (2007) Journal of lipid research 48, 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, and Nedergaard J (2010) The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 7153–7164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Bostrom P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, Virtanen KA, Nuutila P, Schaart G, Huang K, Tu H, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Hoeks J, Enerback S, Schrauwen P, and Spiegelman BM (2012) Cell 150, 366–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz TJ, Huang TL, Tran TT, Zhang H, Townsend KL, Shadrach JL, Cerletti M, McDougall LE, Giorgadze N, Tchkonia T, Schrier D, Falb D, Kirkland JL, Wagers AJ, and Tseng YH (2011) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 143–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang QA, Tao C, Gupta RK, and Scherer PE (2013) Nature medicine 19, 1338–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Himms-Hagen J, Melnyk A, Zingaretti MC, Ceresi E, Barbatelli G, and Cinti S (2000) American journal of physiology 279, C670–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YH, Petkova AP, Mottillo EP, and Granneman JG (2012) Cell Metab 15, 480–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartelt A, and Heeren J (2014) Nature reviews. Endocrinology 10, 24–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harms M, and Seale P (2013) Nature medicine 19, 1252–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]