Abstract

Objective:

To create a novel screening tool that identified patients who were most likely to benefit from pharmacist in-home medication reviews.

Design:

Single-center, retrospective study.

Setting and participants:

A total of 25 homebound patients in Forsyth County, NC, aged 60 years or older with physical or cognitive impairments and enrolled in home-based primary care or transitional and supportive care programs participated in the study. Pharmacy resident-provider pairs conducted home visits for all patients in the study. Pharmacy residents assessed the subjective risk (high, medium, low) of medication nonadherence using information obtained from home visits (health literacy, support network, medications, and detection of something unexpected related to medications). An electronic medical recorde based risk score was simultaneously calculated using screening tool components (i.e., electronic frailty index score, LACE+ index [length of stay in the hospital, acuity of admission, comorbidity, emergency department utilization in the 6 months before admission], and 2015 American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria).

Outcome measures:

The electronic medical record–based screening tool numerical risk scores were compared with pharmacy resident subjective risk assessments using tree-based classification models to determine screening tool components that best predicted pharmacy residents’ subjective assessment of patients’ likelihood of benefit from in-home pharmacist medication review. Following the study, satisfaction surveys were given to providers and pharmacy residents.

Results:

The best predictor of high-risk patients was an electronic frailty index score greater than 0.32 (indicating very frail) or LACE+ index greater than or equal to 59 (at high risk for hospital readmission). Pharmacy residents and providers agreed that homebound patients at high-risk for medication noncompliance benefited from pharmacist time and attention in home visits.

Conclusion:

In homebound older persons, this screening tool allowed for the identification of patients at high-risk for medication nonadherence through targeted in-home pharmacist medication reviews. Further studies are needed to validate the accuracy of this tool internally and externally.

Background

In 2011, nearly 2 million (5.6%) individuals aged 65 years and older living in the United States were identified as completely or mostly homebound.1 Of this population, 70% reported fair or poor health and had twice as many chronic conditions as those who were not homebound. Medical services offered in an office setting can be problematic when caring for medically complex, functionally impaired adults. Home-based primary care (HBPC) is a team-based model of care that provides longitudinal medical services to functionally impaired individuals within their homes. Transitional and supportive care (TSC) is a delivery model that provides an integrated clinical delivery across various health care locations from hospital to home-based care, with home visits usually performed following hospitalizations or emergency department visits. HBPC and TSC are both valuable and unique programs as they allow providers to accurately assess patients’ living environments and adjust care based on their individual needs.2,3

Within the Veterans Affairs (VA) system, HBPC model of care, composed of a physician, pharmacist, and other ancillary health professionals, was associated with a 59% reduction in hospital bed days, 89% reduction in nursing home bed days, and a combined reduction of 78% total inpatient days for functionally impaired, medically complex patients in 2007.4 Literature suggests that HBPC programs outside the VA also positively affected homebound patients; however, pharmacists were not represented on private sector HBPC teams.5 Furthermore, frail, medically complex, homebound patients outside the VA may also benefit from supplemental medical assistance, such as pharmacists, inside the home.

Poor medication adherence and high-risk readmissions are both linked to frailty and polypharmacy, which represent opportunities for pharmacist intervention.6,7 In 1 study, frail patients suffering from polypharmacy had more health problems, 13 times longer hospital stays, were more often discharged to nursing homes, and had a 5 times greater risk of readmission than patients without frailty and polypharmacy.7 Frailty has also been associated with chronic disease states such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, depressive symptoms, hearing impairment, visual impairment, chronic airflow obstruction, chronic kidney failure, and low hemoglobin.8 Given the correlation between medication complexities and poor outcomes among older patients, pharmacists may be considered a valuable addition to HBPC and TSC medical teams.

At the time of this study, patients at Wake Forest Baptist Health who qualified for HBPC were identified by social work, nurses, pharmacists, and providers and were enrolled via referral by both inpatient and outpatient providers to HBPC program. Patients were visited by physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, social workers, or pharmacists depending on the patient’s specific needs. On average, patients were seen at home by their primary care provider once per month; however, depending on their health status and comorbidities, visitation frequencies varied. Each pharmacy resident was paired up with a specific medical provider and followed that provider’s patients longitudinally.

The utilization of pharmacists on HBPC teams is paramount to achieving optimal health outcomes in high-risk patients. Benefits of primary care based, pharmacist-provider collaborative medication therapy management are evident in the literature and have been shown to reduce cost and improve quality of life in addition to reducing emergency department visits and hospitalizations.9–11 The roles and subsequent interventions of a pharmacist in this setting include, but are not limited to, assessing for adherence, medication appropriateness, accessibility, medication administration, and storage.12 Pharmacists are highly skilled clinicians who do not have the ability to bill for home-based medication reviews; thus, patients who are most likely to benefit from in-home pharmacy care and their respective health outcomes need to be well-defined.

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to create a screening tool that identified patients who were at high-risk for medication noncompliance and in need of a pharmacist’s in-home medication review. Secondary objectives were to compare individual components of the electronic medical record-based screening tool with pharmacy residents’ subjective global patient risk assessments.

Methods

Eligible patients were enrolled in HBPC or TSC programs from July to December 2018. The screening tool included information from the electronic medical record (EMR) calculated before pharmacy residents’ in-home visits: electronic frailty index (eFI) scores (a deficit accumulation index that consists of 59 items including diagnoses, laboratory values, and Medicare Annual Wellness functional data),13 LACE+ (length of stay in the hospital, acuity of admission, comorbidity, emergency department utilization in the 6 months before admission) index scores,14 and number of high-risk medications as defined by the 2015 American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria.2 The 2019 Beers Criteria was not available at the time of the study and therefore may not be inclusive of changes made in the updated criteria. The eFI is a model that assesses frailty based on EMR.13 The eFI was developed at Wake Forest Baptist Health and shown to identify vulnerable adult patients in the context of a managed care population by independently predicting all-cause mortality, inpatient hospitalization, emergency department visits, and injurious falls. The eFI categorizes patients as fit (< 0.1), prefrail (0.1 < eFI < 0.21), and frail (> 0.21). The LACE+ index score is commonly used to assess the risk of hospital readmission or death within 30 days of discharge composed of length of stay, acuity of admission, comorbidities identified in the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and emergency department visits within 6 months. LACE+ categorizes patients as low-risk (0–28), moderate-risk (29–58), and high-risk (59+). The Beers Criteria3 is an explicit list of medications created by the American Geriatrics Society to use with caution in geriatric patients. The EMR-based screening tool scores were calculated using patient data from June 2018, before pharmacy resident and provider in-home co-visits. Each score was computed in a different manner given the functionality limitations of the current EMR system. The LACE+ score was calculated directly in the EMR; however, because the eFI was still being researched, its scoring was outsourced to the Wake Forest developer and for manual calculation. However, at the time of this publication, eFI scores are automatically calculated by the Wake Forest EMR. Similarly, because the Beers Criteria requires a level of clinical judgment to assess, each pharmacy resident manually counted the number of potentially inappropriate Beers Criteria medications for their assigned homebound patient before the home visit. Five pharmacy resident and provider pairs visited 25 homebound patients throughout the course of the residency year. Provider credentials included 1 medical doctor (MD), 1 MD in geriatric fellowship training,1 doctor of nursing practice (DNP), and 2 nurse practitioners. As part of their normal job function, HBPC and TSC providers regularly visited a scheduled panel of homebound patients. Pharmacy residents individually aligned their schedules with those of the providers to ensure that home visits were completed together. Each of the 5 residents saw approximately the same patients (4–6 patients) for the purposes of this study. They followed patients longitudinally; however, only the first visit was used in the analysis for this study. Providers completed medical visits and pharmacy residents performed medication reviews, identified medication concerns, and recommended medication changes. Pharmacy residents determined subjective global patient risk assessments (low, medium, or high-risk for medication noncompliance) for each homebound patient after considering health literacy, support network, medications, and detection of something unexpected. For example, a patient with poor health literacy and an unexpected stockpile of expired medications may have required additional support from a pharmacist in the form of a medication chart or visual aid and additional education on medication disposal. However, if that same patient had a caregiver (e.g. nurse practitioner) who appropriately set up the patient’s pillbox weekly and understood the purpose of each medication, the pharmacist may not be an impactful addition to that visit. The listed considerations were used solely as a guide to determine whether the pharmacist was a valuable asset to the home visit. Health literacy, medications, and support network were not formally measured but taken into a holistic assessment by the pharmacy residents. Following the home visits, residents were asked to document whether they uncovered something unexpected during the visit, time spent inside the patient’s home, time spent reviewing medications, number of high-risk medications (assessed using the Beers Criteria), and their subjective risk assessment (low, medium, or high-risk) within the EMR as part of their visit notes. Low-risk patients were defined as those who were unlikely to benefit from pharmacist intervention. Medium-risk patients were defined as those likely to benefit from a pharmacist phone call. High-risk patients were defined as those likely to benefit from a pharmacist in-home medication review. Pharmacy residents were specifically asked to identify high-risk patients if they have found something surprising on the home visit that could not have been identified upon chart review or telephone call. Examples of unexpected findings included expired medications, incorrectly sorted pillboxes, additional over-the-counter and herbal medication stockpiles not represented in the EMR, and improper usage or storage of nebulizer vials. In relation to the examples described, upon revealing something unexpected, pharmacists would intervene by educating patients and caregivers, removing expired medications, correctly organizing pillboxes, ensuring the proper usage and storage of medications, updating the EMR, and scheduling pharmacist follow-up visits as needed. Numerical risk scores calculated by the EMR-based screening tool were then compared to the pharmacy residents’ subjective risk assessments using tree-based classification models. Screening tool scores were compared both individually using scores from single components of the tool (i.e., LACE+, eFI, number of Beers Criteria medications) and comprehensively as 1 composite risk score to determine which combination of screening tool components best predicted a high-risk patient as defined by pharmacy residents’ overall in-home medication review subjective risk assessments. Following the research study, providers and pharmacy residents were provided with satisfaction surveys to determine the need and benefit of a pharmacist on the HBPC and TSC teams. Based on a 5-point Likert Scale, survey responses ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study protocol.

Data analysis

Tree-based classification models were built to find patient demographics and screening tool components that might be predictive of in-home pharmacist consideration of high-risk. We combined the low-risk and medium-risk patients for this method as we were most interested in identifying those patients who would most likely benefit from pharmacists’ in-home medication reconciliation. Factors considered for the tree were age, gender, eFI score, LACE+ index score, and number of Beers Criteria medications, which were then correlated with high-risk patients as defined by pharmacy residents’ subjective assessments. The entropy criterion was used for tree growth, and the cost complexity criterion was used for tree pruning.

Results

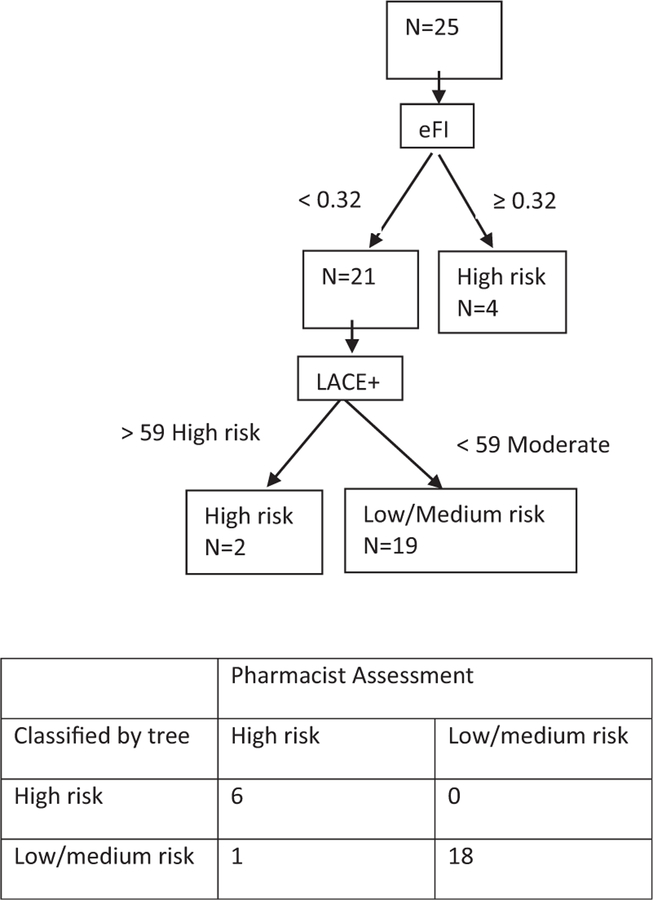

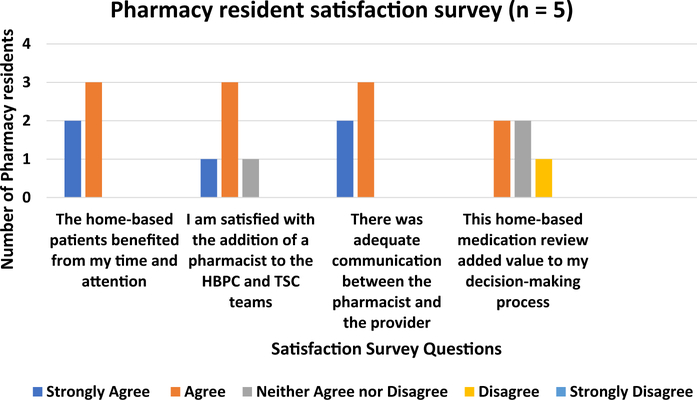

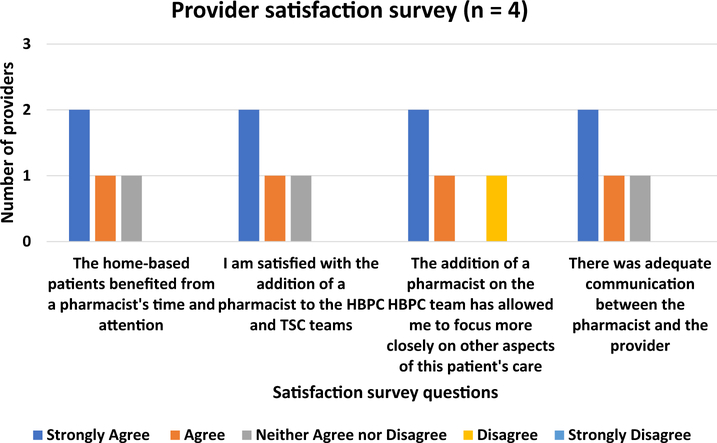

Twenty-five patients received in-home medication reviews by a pharmacist. Seven (28%) patients were subjectively considered high-risk (would benefit from an in-home pharmacist medication review owing to high-risk for medication noncompliance), 5 (20%) patients were subjectively considered medium-risk by the pharmacist (would benefit from pharmacist phone call), and 13 (52%) of the patients were considered low-risk (would not benefit from a pharmacist) as displayed in Table 1. The median number of Beers list medications was 2 (interquartile range (IQR) 1–3), median LACE index score was 53 or moderate-risk of readmission (IQR 48–57), and median eFI score was 0.27 or very frail (IQR 0.15–0.31) as shown in Table 1. The classification tree found that the best predictors of a high-risk patient (i.e. most likely to benefit from a pharmacist in-home medication review) was an eFI greater than 0.32 or LACE+ index greater than or equal to 59 as displayed in Figure 1. Otherwise, the patient was moderate or low-risk and less likely to benefit from a pharmacist in-home medication review. Overall, pharmacy residents (n = 5) thought that home-based patients benefited from their time and attention in the home visits, were satisfied with the addition of a pharmacist to HBPC and TSC teams, and felt that there was adequate communication between the pharmacist and the provider. Pharmacy residents on average “neither agreed nor disagreed” that the home-based medication review added value to their decision-making process (Figure 2). All 5 participating residents completed the provided survey. HBPC providers (n = 4) overall thought that home-based patients benefited from a pharmacist’s time and attention, were satisfied with the addition of a pharmacist to HBPC and TSC teams, believed that a pharmacist on HBPC team allowed them to focus more closely on other aspects of the patient’s care, and felt there was adequate communication between the pharmacist and the provider (Figure 3). Although all 5 providers were given the survey, only 4 providers completed the survey because of the time constraints of this project. One of the 5 providers completed 3 separate surveys for each resident involved in her covisit. This provider’s 3 surveys were averaged and denoted in Figure 3 as 1 survey. The average time pharmacy residents spent in each patient’s home with the provider averaged 58.7 ± 21.9 minutes per visit, and the average time pharmacy residents spent performing in-home medication reviews was 30.2 ± 20.9 minutes per visit.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics stratified by subjective risk assessment

| Characteristics | Low-risk patient (n = 13) | Medium-risk patient (n = 5) | High-risk patient (n = 7) | Overall (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean Age - y ± SD | 84.9 ± 10.3 | 78.0 ± 8.3 | 77.3 ± 8.8 | 81.4 ± 9.9 |

| Female – no. (%) | 11 (84.6%) | 4 (80.0%) | 5 (71.4%) | 20 (80.0%) |

| Mean eFI ± SD | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| eFI score | ||||

| Fit (eFI<0.1) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (8.0%) |

| Prefrail (0.1<eFI<0.21) | 3 (23.1%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 6 (24.0%) |

| Frail (eFI>0.21) | 8 (61.5%) | 3 (60.0%) | 6 (85.7%) | 17 (68.0%) |

| 2015 AGS beers criteria (No of medications) | ||||

| 0 | 4 (30.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (16.0%) |

| 1 | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (20.0%) | 2 (28.6%) | 6 (24.0%) |

| 2 | 4 (30.8%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 7 (28.0%) |

| ≥ 3 | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (40.0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 8 (32.0%) |

| LACE+ index score | ||||

| Moderate-risk 29–58 | 13 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 3 (42.9%) | 21 (84.0%) |

| High-risk ≥ 59 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 4 (16.0%) |

Abbreviations used: eFI, electronic frailty index score; LACE, length of stay in the hospital, acuity of admission, comorbidity, emergency department utilization in the 6 months before admission; AGS, American Geriatric Society.

Figure 1.

Tree-based classification model. Abbreviations used: eFI, electronic frailty index; LACE, length of stay in the hospital, acuity of admission, comorbidity, emergency department utilization in the 6 months before admission.

Figure 2.

Pharmacy resident satisfaction survey results. Abbreviations used: HBPC, home-based primary care; TSC, traditional and supportive care.

Figure 3.

Provider satisfaction survey results. Abbreviations used: HBPC, home-based primary care; TSC, transitional and supportive care.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop an EMR-based screening tool to best align with pharmacy residents’ identification of a patient at high-risk for medication noncompliance and in need of a pharmacist in-home medication review. The combination of an eFI greater than 0.32 or LACE+ greater than or equal to 59 successfully identified all “high-risk” patients who were subjectively identified by pharmacy residents’ global categorization as in need of in-home pharmacist intervention after conducting a home visit. The electronic screening tool is valuable because it allows for targeted in-home medication reconciliation for those patients at highest risk for medication noncompliance.

Pharmacy residents visited a total of 25 patients, but only 7 were identified as high-risk after unveiling something unexpected that required a pharmacist intervention that could not have been identified by EMR chart review or a patient phone call. The panel of 25 patients were picked solely based on provider and resident schedule availability, so risk factors and need-based considerations were not used to allocate pharmacy residents preemptively. Therefore, most (18 of 25, 72%) of the patients who were seen by a pharmacist did not, in fact, require a pharmacist’s in-home medication review based on the residents’ perceptions of the patient and home. Those who were subjectively characterized as high-risk for medication noncompliance had an eFI score greater than 0.32 and LACE+ score greater than or equal to 59. Although Wake Forest created and validated their own version of eFI,13 other studies have validated similar eFI scoring systems that predict the risk of nursing home admission, hospitalization, and mortality.15 The eFI categorization (fit, prefrail, frail) differed slightly in this study from those used in other studies (fit, mild frailty, moderate frailty, severe frailty); however, the correlation between eFI score and outcomes were consistent. In this study, a higher eFI score greater than 0.32 (frail) was associated with the need for an in-home pharmacist visit. This suggests that there is a positive correlation between frailty and actionable pharmacy-related problems and aligns with previous studies regarding frailty and polypharmacy.7 Similar to the eFI, an elevated LACE+ score (high-risk of readmission) is indicative of pharmacy-related concerns and warrants a pharmacist in-home medication review. An elevated LACE+ score implies frequent hospital admissions and thus frequent medication changes, which may lead to confusion and medication complications. Interestingly, the number of potentially inappropriate Beers Criteria medications did not considerably affect the need for in-home pharmacist medication review. This lack of correlation was likely because of the current state of patients who were enrolled in the HBPC program. Most house-call patients have been under the care of geriatric providers for an extended period of time and may have already had high-risk medications tapered off. In addition, Beers Criteria is a list of potentially inappropriate medications, implying that medications on this list may be clinically warranted in certain circumstances. Owing to the controversy around Beers Criteria medications and the vast amount of clinical judgment required to access appropriateness, the correlation between the number of Beers Criteria medications and the need for a pharmacist was not seen in this study. Therefore, either an elevated eFI or LACE+ score was appropriately correlated with the need for pharmacist medication review and intervention.

Pharmacy residents and providers were provided surveys to determine satisfaction rates following the inclusion of a pharmacist on the HBPC team. Residents overall agreed that patients benefited from their time and attention in the home visits; however, opinions about the benefit of home visits in regard to clinical decision making was inconsistent among residents. As mentioned previously, only 7 of the 25 patients seen by pharmacy residents truly required a pharmacist’s time and attention in the home visits. Therefore, the survey results aligned with subjective risk assessments as most home visits did not reveal something unexpected that required a pharmacist medication intervention. In contrast, providers agreed that home-based patients benefited from a pharmacist’s time and attention. They were overall satisfied with the addition of a pharmacist to HBPC and TSC teams, which allowed providers to focus more closely on other aspects of the patient’s care. The time needed to complete medication reviews was also assessed during the study. Pharmacists spent an average of 30 minutes on in-home medication reviews and spent approximately 1 hour in the home per visit. The discrepancy between the time needed to complete the medication review and length of the visit was largely because of the visit being a covisit with the provider. The pharmacy resident stayed in the home until the provider had also completed their visit. This is not currently a feasible task of nonresident pharmacists at Wake Forest Baptist as many of the patients seen did not in fact require a pharmacy-specific intervention. Future steps include utilizing this tool to identify high-risk patients in an effort to streamline home visits so that all pharmacist home visits are beneficial.

There were several limitations to this study that offer opportunities to improve future studies. The small sample size may have masked correlation between subjectively defined high-risk patients and the number of Beers Criteria medications and the composite eFI, LACE+, and number of Beers Criteria medications score. The small sample size was largely owing to the inability of pharmacy residents to visit all HBPC and TSC patients over the course of several months. Furthermore, the addition of a pharmacy resident to the HBPC program was new and dynamic as several changes occurred throughout the year to accommodate resident schedules as this was a longitudinal experience. Because this experience was new to both providers and residents alike, expectations of the resident were not yet defined at the beginning of the study. As noted in the methods, 1 provider completed 3 surveys for each of the 3 residents with which she performed co-visits. Inconsistency in resident performance not only represented a learning curve for providers and residents but it also mimicked the variability among pharmacist clinical judgment, which is likely to occur in settings beyond this study. Finally, the outcome, identification of a high-risk patient that is being modeled is a subjective global measure by a pharmacy resident. In future studies, perhaps characterizing patients based on pharmacist recommendations and implementations made at the time of the home visit may be a more tangible measure of medication-related risk.

Next steps include broadening this electronic-based screening tool in EMR to the entire Wake Forest House Call Program (current census of approximately 100 longitudinal patients and 50 transitional patients per month) to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from an in-home pharmacist medication review and assessing the accuracy of the tool. After the conclusion of this study, the EMR-based screening tool was used to identify a list of high-risk patients currently enrolled in HBPC or TSC programs. Future pharmacy residents will use this list to screen, target, and therapeutically intervene on the most vulnerable patients for home-based pharmacist review. Analysis of the screening tool’s accuracy in a larger sample of patients is needed in future studies to validate the applicability of the tool to the entire health care system and other health care systems interested in population management.

Conclusion

Although pharmacists are highly skilled clinicians, they are not well represented among private sector home-based primary care teams. Given the inability to bill for pharmacist home-based medication reviews, a screening tool was created to identify patients most likely to benefit from in-home pharmacy care. This screening tool allowed for the identification of high-risk homebound older patients subjectively determined by pharmacy residents through targeted in-home pharmacist medication reviews. Surveys distributed to providers and pharmacy residents demonstrated that the addition of a pharmacist to home-based primary care and transitional and supportive care teams was beneficial to both patients and providers alike. Further studies are needed to internally and externally validate the novel screening tool.

Key Points.

Background:

In 2011, nearly 2 million (5.6%) individuals aged 65 years and older living in the United States were identified as completely or mostly homebound.

Home-based primary care programs outside the Veteran’s Affairs system positively affect homebound patients; however, pharmacists are not well represented on private sector home-based primary care teams.

Pharmacists are highly skilled clinicians who do not have the ability to bill for home-based medication reviews; thus, patients most likely to benefit from in-home pharmacy care need to be well defined.

Findings:

The best predictor of high-risk patients using an electronic medical recordebased screening tool was an electronic frailty index greater than 0.32 or LACE+ index (length of stay in the hospital, acuity of admission, comorbidity, emergency department utilization in the 6 months before admission) greater than or equal to 59.

The screening tool allowed for the identification of homebound older patients at high risk for medication nonadherence.

Further studies are needed to validate the accuracy of this tool.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Biostatistics Core of the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute for the analysis and interpretation of data.

Funding: Rachel Zimmer is funded by Health Resources and Services Administration’s Geriatric Academic Career Award (HRSA; K01KP33462).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest or financial relationships.

Contributor Information

Amy E. Stewart, Clinical Pharmacist, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC.

James F. Lovato, Senior Biostatistician, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC

Rachel Zimmer, Assistant Professor, Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC.

Alyssa P. Stewart, Clinical Pharmacist, Specialty Pharmacy Services, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC

Molly T. Hinely, Pharmacy Clinical Coordinator, Population Health, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC

Mia Yang, Assistant Professor, Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC.

References

- 1.Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7): 1180–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American geriatrics society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Totten AM, White-Chu EF, Wasson N, et al. Home-based Primary Care Interventions. Rockville (MD): Agency for Research and Quality (US); 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beales JL, Edes T. Veteran’s affairs home based primary care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25(1):149–154. viii-ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stall N, Nowaczynski M, Sinha SK. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2243–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jankowska-Polańska B,Zamȩta K,Uchmanowicz I,Szymańska-Chabowska A, Morisky D, Mazur G Adherence to pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of frail hypertensive patients. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018;15(2):153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosted E, Schultz M, Sanders S. Frailty and polypharmacy in elderly patients are associated with a high readmission risk. Dan Med J. 2016;63(9): A5274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng TP, Feng L, Nyunt MSZ, Larbi A, Yap KB. Frailty in older persons: multisystem risk factors and the Frailty Risk Index (FRI). J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(9):635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch JD, Bounthavong M, Arjmand A, et al. Estimated cost-effectiveness, cost benefit, and risk reduction associated with an endocrinologist-pharmacist diabetes intense medical management “tune-up” clinic. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(3):318–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polgreen LA, Han J, Carter BL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a physician-pharmacist collaboration intervention to improve blood pressure control. Hypertension. 2015;66(6):1145–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matzke GR, Moczygemba LR, Williams KJ, Czar MJ, Lee WT. Impact of a pharmacist–physician collaborative care model on patient outcomes and health services utilization. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(14): 1039–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amruso NA, O’Neal ML. Pharmacist and physician collaboration in the patient’s home. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(6):1048–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pajewski NM, Lenoir K, Wells BJ, Williamson JD, Callahan KE. Frailty screening using the electronic health record within a Medicare accountable care organization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(11): 1171–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damery S, Combes G. Evaluating the predictive strength of the LACE index in identifying patients at high risk of hospital readmission following an inpatient episode: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ (Open) 2017;7(7):–016921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]