Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate if the use of an indirect braces bonding protocol for localized enamel etching and adhesive application could help reduce plaque accumulation and demineralization around the brackets compared with a conventional direct-bonding technique.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty patients were bonded with a split-mouth approach: two randomly selected opposite quadrants were used as the test sides and the other two as control sides. During the first 6 months, the plaque presence around the braces was recorded monthly according to a plaque accumulation index (PAI), as was the presence of demineralization. PAI values were measured at each of the four bracket sides for every bonded tooth. Analysis of variance was used to identify significant differences between different bracket margins and between test and control sides.

Results:

Test and control sides differed significantly for PAI measurements from t1 (1 month after bonding) to t4 (4 months after bonding), with the highest value of significance (P < .001) at t1 but with no significant differences from t5 to t7 (treatment end). Considering whole-mouth results, different bracket margin PAI scores did not differ significantly. PAI scores were higher at t1 and progressively decreased during the treatment. At debonding, the onset of 21 new white spots was recorded overall for the control sides and eight new white spots for the test sides.

Conclusion:

Especially during the first 4 months after brackets placement, this indirect bonding protocol allowed for significant reduction in plaque accumulation around the braces and reduced onset of white spots during the orthodontic treatment.

Keywords: Plaque accumulation, Indirect bonding, Orthodontics, Oral hygiene, Braces, Brackets

INTRODUCTION

Compared to direct manual positioning, indirect braces bonding with transfer masks is a technique that, when standardized, allows reduction in patient chair time, a more accurate braces placement, and a reduced composite excess around the braces. The reduction in chair time concerns not only initial bracket positioning but also persists throughout the therapy because the positioning of the braces is more accurate; thus, fewer compensatory bends must be introduced into the arch wire during the occlusal seating phase or there is less need for repositioning of poorly placed brackets.1–3 This technique is also less operator sensitive and allows even relatively inexperienced orthodontists to obtain results that otherwise might be difficult to achieve.4–6

Different techniques of indirect bonding have been proposed, employing changes to the transfer mask type (eg, single jigs or full arch), the material used (eg, acrylic resin, silicone, thermo-printed material, or a combination of two or more of these materials), and the type of preparation of the bracket base (eg, personalized or not through a self- or light-cured resin).7,8

Braces are usually placed in the middle of the clinic crown, so that the center of the slot coincides with the center of the crown itself, with the mesial and distal margins of the base aligned to the long axis of the clinic crown. As an alternative, some straight wire techniques include consideration of the bracket placement at a variable distance, depending on the tooth to be bonded, from the incisal margin, but always keeping the alignment with the long axis of the clinic crown.9

Indirect transfer systems are used especially when the braces are placed on the lingual surface of the teeth, but they are also useful in the classic vestibular placement of the orthodontic brackets. This choice is particularly the case when the clinician considers it necessary for some teeth to move away from the average heights and inclinations recommended in the placement chart for the chosen braces. This situation can arise, for instance, when teeth are especially overcrowded, making it impossible to fix the braces in the ideal position the first time, or when the orthodontist wants to facilitate hypercorrection of an extremely rotated tooth.10

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the use of an indirect braces bonding technique could help reduce plaque accumulation around the brackets and the formation of demineralization of the surrounding enamel at the end of the orthodontic treatment.11–14

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study involved 30 patients between the ages of 11.2 and 12.8 years (13 boys and 17 girls) consecutively attending an orthodontics department of a university and undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment (Victory braces, Low Profile series, MBT prescription, 0.022-inch slot, power arm on canines, 3M Unitek). We determined the sample size according to previously published data to obtain a power of 0.8 and an alpha level of at least .05.15 Exclusion criteria were presence of systemic or local (caries, periodontal pockets, mucosal alterations) pathologies, need for surgical or extended restorative adjunctive procedures, enamel development alterations, and dietary restrictions or intolerances. The study protocol was approved by our institutional review board.

The first step was one or more sessions of oral hygiene, instruction, and motivation, essential for the patient to reach a hygienic maintenance level and capacity compatible with the application of a fixed multibracket orthodontic appliance16–20 and to evaluate and record the possible presence of white spots on the buccal surfaces of the teeth. Then, we took each patient's dental impressions with an addition of silicone at two viscosities, putty and flow, and in two phases, applying the more fluid material on the first impression after the setting of the more viscous material (the putty).

The space for the flow silicone can be created by either removal with a scalpel of some silicone from the impression taken with the putty or during the making of the first impression by interposing a sheet of polypropylene between the dental arch and the putty itself to act as a space maker for the flow silicone.

The working models were cast using a type IV white extra-strong orthodontic stone and coated with two thin layers of insulating fluid for plaster (Separating Fluid, Ivoclar Vivadent AG). Braces were placed on the working models and fixed with an easily removable adhesive (Vinavil, Vinavil SpA). After hardening of the adhesive, the perimeter of the base of each bracket was marked on the model with a thin-tip marker pen. At this stage, a first bracket transfer matrix in a soft material (Copyplast 0.5 mm, Scheu Dental GmbH) was prepared with a pressure molding machine (Biostar VI, Scheu Dental Technology). After the excess was removed by cutting with scissors, we embedded the model in pellets reaching the gingival half of the braces and developed a second transfer matrix with a 1-mm thick Duran (Scheu Dental GmbH) foil. The model was soaked in water for 1 hour, after which the two masks, with the fixed braces inside and the residual adhesive on the base of the braces, were removed. The excess from the second sheet was removed by cutting with scissors, and some incisions perpendicular to the slot were made in the sheet of Copyplast 0.5 mm. A mask in Duran 1 mm was prepared on the working model, now without braces, that then was cut out at 2 mm apical to the gingival margins. Holes were made in these on the buccal surfaces of the teeth, following the perimeters of the braces drawn before with the marker pen.

The braces bonding was achieved, starting from the upper arch, using a split-mouth technique, with bonding randomly to one half-arch with a classic direct technique and the other half-arch with the indirect bonding protocol. In the lower arch, the two tests and control sides were crossed so that on both the right and the left sides, there was one half treated with the direct technique and the other with the indirect technique. This design was intended to avoid any bias resulting from right-handedness or left-handedness in patients. Randomization was performed by alphabetically listing patients and progressively assigning them a number between 1 and 30, then using a randomization table to rearrange the numbers into two columns, representing the two possible bonding procedures: upper right half-arch directly bonded or upper right half-arch indirectly bonded. The Duran and the transfer masks were used only on the test sides.

At the time of braces bonding, the masks were first fitted on the dental arches to check the correct and complete possibility of insertion, then all buccal dental surfaces were cleaned with a rotating brush and a fluoride-free silicate-based polishing paste (Zircate, Dentsply) and gently air dried. The isolation kit Nola Dry Field System (Great Lakes Orthodontics, Tonawanda, NY) was applied, formed by a double cheek retractor and a tongue basket linked by thin saliva ejector silicone tubes to the aspiration system of the chair. The two Duran masks were inserted, and orthophosphoric acid at 37% was applied for 30 seconds into the buccal holes (Figure 1). Then the acid was aspirated and the masks were removed and separately washed and dried.

Figure 1.

Enamel etching using the Duran masks with holes in two opposite half-arches.

Successively, both full arches were washed and air dried; the two control half-arches were acid etched with the same product, washed, and dried. Then the Duran mask was inserted and the orthodontic adhesive applied into the buccal holes on the test sides and light cured. Finally, this mask was carefully removed, and the double transfer mask with the braces was applied; the bases were cleaned with a cotton ball bathed in acetone, followed by application of a small amount of light-curing orthodontic adhesive.

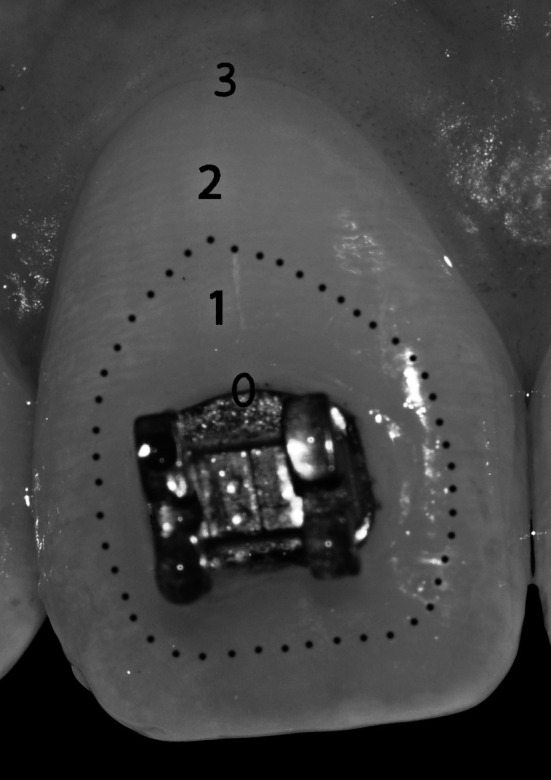

Once the two transfer masks were completely fitted, the light-curing lamp was used for 20 seconds on each tooth: 10 seconds on the mesial and 10 seconds on the distal edge of every single bracket. Afterward, the first external stiff mask was removed, followed by the internal soft mask, proceeding from distal to mesial and from lingual to vestibular (Figure 2). The control sides were directly bonded with the same light-curing protocol and adhesive product. Possible composite excess was removed with a sharp-pointed dental scaler and followed by application of the rotating brush with the polishing paste. Finally, we took pictures of any white spots present at the beginning of the treatment (t0), and the patients were trained again in hygienic home procedures.

Figure 2.

The two transfer masks completely fitted on the test sides (on the upper arch the Duran mask is already removed).

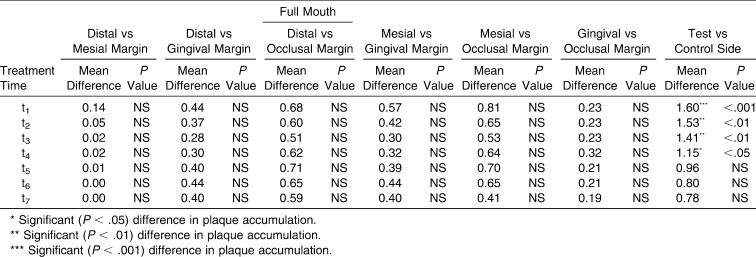

Afterward, the patients were treated by an orthodontist who was blinded to the study aims. For the first 6 treatment months, monthly recordings (from t1 to t6) were made of plaque presence around the braces according to a plaque accumulation index (PAI), using a numerical scale from 0 to 3 to evaluate the amount of plaque accumulated between the occlusal, mesial, apical, and distal margins of the bracket and the corresponding dental margin. Scores were assigned as follows: 0 if plaque was absent, 1 if there was plaque accumulation on the bracket margin that did not cover half of the distance between the bracket and tooth margins, 2 if the accumulated plaque covered at least half of the distance between the bracket and tooth margins, and 3 if the plaque reached the dental margin (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Plaque accumulation index (PAI). The dotted line marks half of the distance between the bracket and the dental margins, and PAI score numbers are placed in their corresponding positions.

During the orthodontic treatment, the patients underwent sessions of professional oral hygiene every 6 months. The onset of possible decay during the treatment was reported in the same chart where the PAI was recorded, specifying the site, extension, and depth of the decay.

At the end of the treatment (t7), which lasted on average 2 years and 6 months ± 4 months, braces were debonded, final intraoral pictures were analyzed, and the presence of white spots was noted.

A third operator used analysis of variance to statistically evaluate the data and was blinded regarding the origins of the measurements provenience. Significance level was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

From time t0 to time t6, the decay incidence in the group of studied patients was equal to 0. At time t7, the analysis of the medical records showed that in one patient, two D2 dental caries were detected and treated, corresponding to the 2.5 mesial sites and 4.4 distal sites on the test sides, as was one D3 caries in the distal zone of 1.5 on the control side. In another patient, a single D2 caries was diagnosed and treated in the distal zone of 4.5 on the control side. In the 28 remaining patients, there was no decay onset detected.

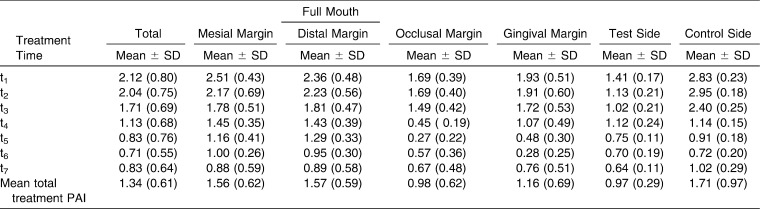

Table 1 summarizes the mean PAI values for each single tooth, considering the global number of teeth on which braces were placed, separating control from test sides, and separating every bracket margin from the others. Table 2 shows mean differences and P values for different margins and for the test vs control sides. Test side PAI measurements were significantly lower than control side measurements from t1 to t4, with the highest significance (P < .001) at t1 but with no significant differences (P >.05) from t5 to t7.

Table 1.

Mean Plaque Accumulation Index (PAI) and Standard Deviation (SD)

Table 2.

Mean Differences Between Different Bracket Edges and Between the Direct and Indirect Bonding Techniques

At time t0, nine white spots were found on the buccal surfaces of the teeth that were successively bonded. At time t7, there were 21 new white spots of different sizes on the control sides and eight new white spots on the test sides; thus, the test sides had fewer new white spots emerge.

DISCUSSION

The results do not indicate a significant difference in the onset of decay in patients treated with a fixed multibracket orthodontic appliance relative to the use of a direct rather than indirect bonding technique. With regard to the plaque accumulation on the bracket margins, it was generally greater during the first months of treatment and tended to decrease gradually during the treatment, perhaps because of improved patient ability to maintain correct oral hygiene, overcoming the initial difficulties linked to braces application.

We hypothesized that plaque could tend to accumulate mainly on the mesial and distal tooth margins, under the arch and on the apical margin, which is often very close to the free gingival margin. Furthermore, it could be present in small amounts on the occlusal margin, which is more easily cleaned with daily oral hygiene; however, we found no statistically significant differences in these values.

Finally, concerning the differences between direct and indirect bonding, there was a significantly greater presence of white spots at the end of the treatment and a greater plaque accumulation around the braces where the direct bonding technique was used, even if only during the first 4 months of treatment.

Considering that enamel demineralization around bracket margins is often due to plaque accumulation and that composite excess around braces facilitates plaque retention, a possible explanation for the results of this study is that the use of an individualized mask for focused adhesive application allowed for a significant reduction in composite excess.

Furthermore, considering that etched enamel roughness increases plaque adhesion, the use of the same individualized mask for focused enamel etching allowed for a significant reduction in the etched enamel area around bracket bases, thus reducing the availability of plaque-retentive rough surfaces.

From the clinical point of view, our results suggest that using this technique could help to reduce the enamel demineralization, which is an unpleasant side effect at the end of orthodontic treatment.

The potential bias of this study was reduced by the use of a blind design that prevented operators from unconsciously collecting and interpreting data based on preconceptions or previous assumptions. Potential bias was further reduced by employing a randomized split-mouth design that precluded any bias resulting from right-handedness or left-handedness in patients.

CONCLUSIONS

This indirect bonding protocol allowed for a significant reduction in plaque accumulation around the braces during the first 4 months after brackets placement and for a reduced onset of white spots during the orthodontic treatment.

Considering whole-mouth results, plaque accumulation around different bracket margins did not differ significantly.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joiner M. In-house precision bracket placement with the indirect bonding technique. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:850–854. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koo B. C, Chung C. H, Vanarsdall R. L. Comparison of the accuracy of bracket placement between direct and indirect bonding techniques. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116:346–351. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shpack N, Geron S, Floris I, Davidovitch M, Brosh T, Vardimon A. D. Bracket placement in lingual vs labial systems and direct vs indirect bonding. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:509–517. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0509:BPILVL]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas R. G. Indirect bonding: simplicity in action. J Clin Orthod. 1979;13:93–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholz R. P. Indirect bonding revisited. J Clin Orthod. 1983;17:529–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodge T. M, Dhopatkar A. A, Rock W. P, Spary D. J. The Burton approach to indirect bonding. J Orthod. 2001;28:267–270. doi: 10.1093/ortho/28.4.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zachrisson B, Brobakkeen B. Clinical comparison of direct versus indirect bonding, with different bracket types adhesives. Am J Orthod. 1978;74:62. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(78)90046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguirre M. J, King G. J, Waldrom M. J. Assessment of bracket placement and bond strength when comparing direct bonding technique. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:269. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong D, Shen G, Petocz P, Darendeliler M. A. A comparison of accuracy in bracket positioning between two techniques—localizing the centre of the clinical crown and measuring the distance from the incisal edge. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:430–436. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bracco P, Vercellino V. Basic classification of 150 dysgnathic subjects according to Ricketts, Steiner and Cervera. Minerva Stomatol. 1980;29:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson P. E, Pender N, Higham S. M. Quantifying enamel demineralization from teeth with orthodontic brackets—a comparison of two methods. Part 1: repeatability and agreement. Eur J Orthod. 2003;25:149–158. doi: 10.1093/ejo/25.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson P. E, Pender N, Higham S. M. Quantifying enamel demineralization from teeth with orthodontic brackets—a comparison of two methods. Part 2: validity. Eur J Orthod. 2003;25:159–165. doi: 10.1093/ejo/25.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livas C, Kuijpers-Jagtman A. M, Bronkhorst E, Derks A, Katsaros C. Quantification of white spot lesions around orthodontic brackets with image analysis. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:585–590. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2008)078[0585:QOWSLA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tufekci E, Dixon J. S, Gunsolley J. C, Lindauer S. J. Prevalence of white spot lesions during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:206–210. doi: 10.2319/051710-262.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodge T. M, Dhopatkar A. A, Rock W. P. A randomized clinical trial comparing the accuracy of direct versus indirect bracket placement. J Orthod. 2004;31:132–137. doi: 10.1179/146531204225020427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ay Z. Y, Sayin M. O, Ozat Y, Goster T, Atilla A. O, Bozkurt F. Y. Appropriate oral hygiene motivation method for patients with fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:1085–1089. doi: 10.2319/101806-428.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arici S, Alkan A, Arici N. Comparison of different toothbrushing protocols in poor-toothbrushing orthodontic patients. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:488–492. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bock N. C, von Bremen J, Kraft M, Ruf S. Plaque control effectiveness and handling of interdental brushes during multibracket treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:408–413. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin M. Y, Busscher H. J, Evans R, Noar J, Pratten J. Early biofilm formation and the effects of antimicrobial agents on orthodontic bonding materials in a parallel plate flow chamber. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28:1–7. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cji094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Øgaard B, Alm A. A, Larsson E, Adolfsson U. A prospective, randomized clinical study on the effects of an amine fluoride/stannous fluoride toothpaste/mouth rinse on plaque, gingivitis and initial caries lesion development in orthodontic patients. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28:8–12. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cji075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]