We wish to report the detection of vanA and vanC genes in Enterococcus gallinarum, because the detection of vanA genes in a motile enterococcus has potentially important implications for infection control practice in hospitals.

Since 1986, vancomycin-resistant E. faecium and E. faecalis have become major nosocomial pathogens in the United States and in several European countries (1, 7). Two principal phenotypes of acquired vancomycin resistance have been described, VanA and VanB, encoded by two distinct gene clusters, the vanA and vanB clusters (5). Both genes are mobile on either plasmids or transposons. The vanA genes typically confer high-level resistance to vancomycin (MIC ≥ 128 mg/liter) and teicoplanin (MIC ≥ 16 mg/liter), while vanB genes typically result in moderate to high-level resistance to vancomycin (MIC = 16 to 64 mg/liter). However, vanA and vanB genotypes associated with different resistance phenotypes have been reported. The motile enterococci, E. gallinarum, E. casseliflavus, and E. flavescens, have low-level intrinsic vancomycin resistance (MIC = 4 to 16 mg/liter) due to the vanC-1, vanC-2, and vanC-3 genes, respectively. VanA- and VanB-type resistance in the motile enterococci has been reported on only a few occasions, and as far as we are aware not in Australia (2, 8).

Recently, an E. gallinarum strain (WBG 9213) isolated from a chicken-processing plant was found to have both vanA and vanC genes. This isolate was identified by the Facklam and Collins identification scheme (3). Differentiation between E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus was based on the lack of pigment production on 5% sheep blood agar after 24 h of incubation. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion and E test (AB Biodisk, Sweden) methods by using Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% horse blood, and by using the Vitek GPS-TB card (bioMérieux-Vitek). The interpretative criteria of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) were used for determining susceptibility of the isolates (6). WBG 9213 grew on the NCCLS vancomycin resistance screening test plate, brain heart infusion agar supplemented with 6 mg of vancomycin per liter.

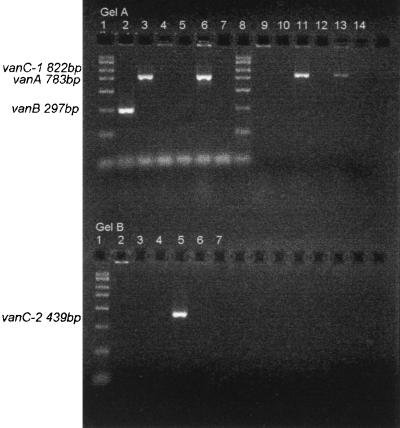

The van genes were detected by PCR using the oligonucleotide primers for vanA, vanB, vanC-1, and vanC-2 genes as reported by Free and Sahm (4). The target gene and product size for each of the control strains are described in Fig. 1. vanA and vanB amplifications were performed as a multiplex reaction. vanC-1 and vanC-2 amplifications were performed separately.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of vanA, vanB, vanC-1, and vanC-2 PCR products. (A) Multiplex vanA and vanB gene PCR (lanes 2 to 7) and vanC-1 gene PCR (lanes 9 to 14). Lanes: 1 and 8, Amresco PCR DNA marker; 2, E. faecalis ATCC 51299 vanB, 297 bp (product size, 297 bp); 3, E. faecium wild strain vanA, 783 bp (product size, 783 bp); 4, E. gallinarum NCTC 11428 vanC-1, 822 bp (no product detected); 5, E. casseliflavus ATCC 25788 vanC-2, 439 bp (no product detected); 6, WBG 9213 (product size, 783 bp); 7, water control; 9, E. faecalis ATCC 51299 vanB, 297 bp (no product detected); 10, E. faecium wild strain vanA, 783 bp (no product detected); 11, E. gallinarum NCTC 11428 vanC-1, 822 bp (product size, 822 bp); 12, E. casseliflavus ATCC 25788 vanC-2, 439 bp (no product detected); 13, WBG 9213 (product size, 822 bp); 14, water control. (B) vanC-2 gene PCR. Lanes: 1, Amresco PCR DNA marker; 2, E. faecalis ATCC 51299 vanB, 297 bp (no product detected); 3, E. faecium wild strain vanA, 783 bp (no product detected); 4, E. gallinarum NCTC 11428 vanC-1, 822 bp (no product detected); 5, E. casseliflavus ATCC 25788 vanC-2, 439 bp (product size, 439 bp); 6, WBG 9213 (no product detected); 7, water control.

Both the 822-bp (vanC-1) and 783-bp (vanA) PCR products were detected in WBG 9213 (Fig. 1). This isolate had a VanA phenotype. MICs of vancomycin and teicoplanin as determined by the E test were ≥256 and 32 mg/liter, respectively. Vancomycin resistance was confirmed by Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion (no zone detected) and the Vitek GPS-TB card (≥32 mg/liter).

The emergence of acquired and transferable high-level vancomycin resistance in the motile enterococci is of great potential clinical and infection control significance. Enterococci with VanA- or VanB-type vancomycin resistance encoded by vanA and vanB gene clusters, respectively, are a major cause of nosocomial infections in some hospitals in the United States and Europe. Whenever such a strain is detected in a hospital, strict infection control procedures are applied to prevent transmission to other patients. However, motile enterococci with their intrinsic VanC-type low-level vancomycin resistance have not required special infection control measures. This policy may no longer be adequate. When vancomycin resistance is detected by phenotypic methods in enterococci other than E. faecium and E. faecalis, it can no longer be assumed that such isolates are not carrying mobile plasmids or transposons encoding high-level vancomycin resistance. PCR assays need to be done to ensure that these enterococci are not carrying vanA or vanB genes in addition to vanC genes. We now recommend that genotypic testing be routinely performed on all clinical isolates of vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

VanA phenotype resistance is often mediated by self-transferable plasmids that have acquired Tn516-related transposons that carry the vanA gene cluster. Plasmid DNA studies are being performed on the isolate described here and will be the subject of a further report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nosocomial enterococci resistant to vancomycin—United States, 1989–1993. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rev. 1993;42:597–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutka-Malen S, Blaimont B, Wauters G, Courvalin P. Emergence of high-level resistance to glycopeptides in Enterococcus gallinarum and Enterococcus casseliflavus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1675–1677. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.7.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facklam R R, Collins M D. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:731–734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.731-734.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Free L, Sahm D. Detection of enterococcal vancomycin resistance by multiplex PCR. In: Persing D H, editor. PCR protocols for emerging infectious diseases. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Resistance to glycopeptides in enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:545–556. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 8th informational supplement. M100-S8. 18, no. 1. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uttley A H, Collins C H, Naidoo J, George R C. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Lancet. 1988;i:57–58. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshikazu I, Ohno A, Kashitani S, Iwata M, Yamaguchi K. Identification of vanB-type vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus gallinarum from Japan. J Infect Chemother. 1996;2:102–105. doi: 10.1007/BF02350850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]