Abstract

Adenosine (Ado) receptors have been instrumental in the detection of heteromers and other higher-order receptor structures, mainly via interactions with other cell surface G-protein-coupled receptors. Apart from the first report of the A1 Ado receptor interacting with the A2A Ado receptor, there has been more recent data on the possibility that every Ado receptor type, A1, A2A, A2B, and A3, may interact with each other. The aim of this paper was to look for the expression and function of the A2A/A3 receptor heteromer (A2AA3Het) in neurons and microglia. In situ proximity ligation assays (PLA), performed in primary cells, showed that A2AA3Het expression was markedly higher in striatal than in cortical and hippocampal neurons, whereas it was similar in resting and activated microglia. Signaling assays demonstrated that the effect of the A2AR agonist, PSB 777, was reduced in the presence of the A3R agonist, 2-Cl-IB-MECA, whereas the effect of the A3R agonist was potentiated by the A2AR antagonist, SCH 58261. Interestingly, the expression of the heteromer was markedly enhanced in microglia from the APPSw,Ind model of Alzheimer’s disease. The functionality of the heteromer in primary microglia from APPSw,Ind mice was more similar to that found in resting microglia from control mice.

Keywords: neuroinflammation, neurodegenerative disease, dementia, G protein-coupled receptor, activated microglia, purinergic signaling, striatum, hippocampus, cerebral cortex

1. Introduction

Adenosine (Ado) is a nucleoside that participates in the metabolism of nucleic acids, of enzyme cofactors/substrates (nicotinamide adenine nucleotides, flavin-adenine dinucleotides etc.), and of energy-related relevant molecules, such as ATP. One of the functions of the nucleoside is to be a warning for excess energy expenditure or for hypoxia; in such conditions, ATP is converted to Ado, whose presence activates Ado receptors on the cell surface. There are four Ado receptors whose affinity for Ado varies and that belong to the rhodopsin-like class A G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs): A1, A2A, A2B, and A3. The canonical heteromeric G proteins to which they couple are Gs (A2A and A2B) and Gi (A1 and A3). Accordingly, activation of the A2AR or the A2BR leads to increases of [cAMP] and engagement of the protein kinase A-mediated signaling pathway whereas activation of A1R or A3R leads to decreases in intracellular cAMP levels [1].

GPCRs may form heterodimers and higher-order structures that arise as distinct functional units. Research on Ado receptors has been instrumental to identify a variety of heteromers starting with those established in the striatum with dopamine receptors [2,3]. It was also found that the A1 and A2A receptors are sensors of the Ado concentration via the formation of tetrameric structures complexed with two heterotrimeric G proteins, one Gi and one Gs. At low Ado concentrations, Gi-mediated signaling is predominant whereas at higher concentrations, Gs-mediated signaling predominates [4,5,6]. More recently, heteromers formed by A2A and A2B and by A2A and A3 receptors have been reported, although their physiological function has not yet been fully elucidated [7,8,9].

The A2A receptor (A2AR) is enriched in striatal neurons and was largely considered a target for combating Parkinson’s disease. Noteworthy, a first-in-class selective A2AR antagonist, istradefylline, has been approved as an adjuvant therapy in Parkinson’s disease [10,11,12,13,14,15]. The receptor is a target for neuroprotection in other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s, and in brain injury [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. In addition, altered expression of (individual) adenosine receptors was found in the brain of AD patients [26]. Importantly, the expression of the receptor in microglia from control samples was fairly low whereas the A2AR was markedly upregulated in glial cells in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of AD patients [26]. A first aim of this paper was to look for the differential expression and functionality of complexes formed by the A2AR and the A3R (A2AA3Hets) in different regions of the mice brain.

Age is the main risk factor in AD and, unfortunately, the efforts made to obtain anti-AD drugs have so far failed. Intriguing is the lack of success of therapies based on the benefits provided by a variety of drugs tested in transgenic AD models ([27,28,29] and references therein). A further relevant issue is the lack of appropriate protocols to assess the neuroprotective potential of potential therapeutic drugs in humans [30]. It should, also, be noted that it is doubtful that neurons that progressively die in AD patients can prolong survival by targeting them directly. Alternatively, targeting the glia may be a better option to allow for neuroprotection, especially in those neurological diseases, including AD, in which the microglia are activated [31,32,33].

Acutely, activated proinflammatory and cytotoxic microglial cells are also known as M1. Either by alternative activation pathways or upon phenotypic changes can microglia contribute to repair and regenerate by expressing anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory molecules (M2a cells) or acquire the M2b/c deactivating phenotype, also expressing anti-inflammatory markers [34]. Activation of the A2AR in activated microglia may yet lead to another phenotype, M2d [35,36,37,38]. In this sense, in 2005, we reported iNOS production by primary microglia upon A2AR activation [39].

On the one hand, GPCR-mediated signaling is relevant in the activation of microglia occurring in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [40]; in fact, GPCRs expressed in microglia could be important for regulating the M1 (proinflammatory)/M2 (neuroprotective) balance in these cells [31,35]. On the other hand, adenosine regulates microglial activation via, at least, A2A and A3 receptors [32,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. A second aim of this paper was to look for the differential expression and functionality of the A2AA3Het in primary microglia from control mice and from the APPSw,ind AD mouse model, which carries the transgene for the human amyloid precursor protein (APP) with Swedish and Indiana mutations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

PSB 777 ammonium salt, 2-Cl-IB-MECA, SCH 58261, and PSB 10 hydrochloride were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Concentrated (10 mM) stock solutions prepared in DMSO were stored at −20 °C. In each experimental session, aliquots of concentrated solutions of compounds were thawed and conveniently diluted in the appropriate experimental solution. Lipopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli O111:B4 (LPS) and Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were purchased from SigmaAldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. APP Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

APPSw,Ind transgenic mice (line J9; C57BL/6 background) expressing human APP695 harboring the FAD-linked Swedish (K670N/M671L) and Indiana (V717F) mutations under the PDGF promoter were obtained by crossing APPSw,Ind to non-transgenic (WT) mice [58]. APPSw,Ind-derived embryos or pups, individually genotyped and divided into “APPSw,Ind” and “control”, were used for preparing primary cultures (12 embryos or pups in a typical experiment). Animal care and experimental procedures were in accordance with European and Spanish regulations (86/609/CEE; RD1201/2005). Mice were handled, as per law, by personnel with the ad hoc certificate (issued by the Generalitat de Catalunya) that allows animal handling for research purposes.

2.3. Neuronal and Microglial Primary Cultures

To prepare primary striatal neurons, brains from the fetuses of pregnant C57/BL6J mice were removed (gestational age: 17 days). Neurons were isolated as described in [59] and plated at a confluence of 40,000 cells/0.32 cm2. Briefly, the samples were dissected, carefully stripped of their meninges, and digested with 0.25% trypsin for 20 min at 37 °C. Trypsinization was stopped by adding an equal volume of culture medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium-F-12 nutrient mixture, Invitrogen). Cells were brought to a single cell suspension by repeated pipetting followed by passage through a 100 μm-pore mesh. Pelleted (7 min, 200 g) cells were resuspended in supplemented DMEM and seeded at a density of 3.5 × 105 cells/mL in 6-well plates for functional assays and 12-well plates for PLA assays. For neuronal cultures, the day after, medium was replaced by neurobasal medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, and 2% (v/v) B27 (GIBCO). Primary microglia were obtained from 2–3-day-old pups and processed as described above for neurons but instead of neurobasal/B27, using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, MEM Non-Essential Amino Acid Solution (1/100), and 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS). All supplements were from Invitrogen (Paisley, Scotland, United Kingdom). Cells were maintained in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C and were used for assays after 15 days of culture. For LPS-activated microglia, 48 h before initiating the experiment, 0.01% (v/v) LPS and 0.002% (v/v) IFN-γ were added to Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium where microglial cells were kept.

2.4. cAMP Determination

Microglial and neuronal primary cultures were plated in 6-well plates. Two hours before initiating the experiment, cell-culture medium was replaced by non-supplemented DMEM medium. Then, cells were detached, resuspended in non-supplemented DMEM medium containing 50 μM zardaverine, and plated in 384-well microplates (2500 cells/well). Cells were pretreated (15 min) with the corresponding antagonists (1 µM SCH 58261 for A2AR and 1 µM PSB 10 for A3R) or vehicle and stimulated with agonists (100 nM PSB 777 for A2AR and 100 nM 2-Cl-IB-MECA for A3R) (15 min) before the addition of 0.5 μM FK or vehicle. Finally, reaction was stopped by addition of the Eu-cAMP tracer and the ULight-cAMP monoclonal antibody prepared in the “cAMP detection buffer” (PerkinElmer). All steps were performed at 25°. Homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer (HTRF) measures were performed after 60 min of incubation at RT using the Lance Ultra cAMP kit (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Fluorescence at 665 nm was analyzed on a PHERAstar Flagship microplate reader equipped with an HTRF optical module (BMG Lab Technologies, Offenburg, Germany).

2.5. MAPK Phosphorylation Assays

To determine MAP kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation, primary striatal neurons and microglia were plated (50,000 cells/well) in transparent Deltalab 96-well plates and kept in the incubator for 15 days. Then, 2 h before the experiment, the medium was replaced by non-supplemented DMEM medium. Next, the cells were pre-treated at RT for 10 min with antagonists (1 µM SCH 58261 for A2AR and 1 µM PSB 10 for A3R) or vehicle and stimulated for an additional 7 min with selective agonists (100 nM PSB 777 for A2AR and 100 nM 2-Cl-IB-MECA for A3R). Then, cells were washed twice with cold PBS before the addition of 30 µL/well “Ultra lysis buffer” -PerkinElmer- (15 min treatment). Afterwards, 10 μL of each supernatant were placed in white ProxiPlate 384-well microplates and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was determined using an AlphaScreen® SureFire® kit (PerkinElmer) following the instructions of the supplier, and using an EnSpire® Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.6. Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA)

Physical interaction between A2AR and A3R were detected using the Duolink in situ PLA detection Kit (OLink; Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden) following the instructions of the supplier. Primary neurons and microglia were grown on glass coverslips, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed with PBS containing 20 mM glycine to quench the aldehyde groups, and permeabilized with the same buffer containing 0.05% Triton X-100 (20 min). Then, samples were successively washed with PBS. After 1 h of incubation at 37 °C with the blocking solution in a pre-heated humidity chamber, cells were incubated overnight in the antibody diluent medium with a mixture of equal amounts of mouse anti-A2AR (1/100; 05-717, Millipore Corp, Billerica, MA, USA) and rabbit anti-A3R (1/100; ab197350, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) to detect A2AR-A3R complexes. Neurons and microglia were processed using the PLA probes detecting primary antibodies (Duolink II PLA probe plus and Duolink II PLA probe minus) diluted in the antibody diluent solution (1:5). Ligation and amplification were conducted as indicated by the supplier. Samples were mounted using the mounting medium with Hoechst (1/100; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to stain nuclei. Samples were observed in a Zeiss 880 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an apochromatic 63× oil immersion objective (N.A. 1.4) and 405 nm and 561 nm laser lines. For each field of view, a stack of two channels (one per staining) and four Z stacks with a step size of 1 μm were acquired. The number of neurons containing one or more red spots versus total cells (blue nucleus) was determined, and the unpaired t-test was used to compare the values (red dots/cell) obtained.

2.7. Data Handling and Statistical Analysis

Data from immunofluorescence and functional assays were analyzed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The data are the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 18.0 software. Significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post hoc test. Significant differences were considered when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Differential Expression of A2AA3Hets in Primary Neurons from the Cortex, Striatum, and Hippocampus

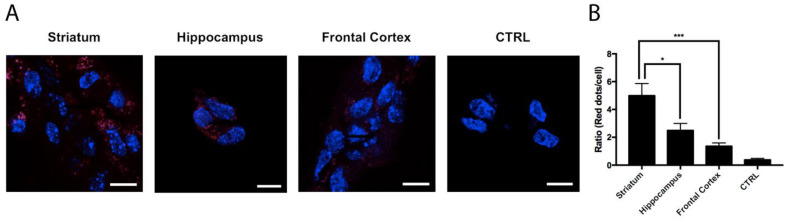

Using the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA), which is instrumental to the detection of complexes formed by two proteins in natural cells and in tissue sections, the expression of A2AA3Hets was assessed in primary neurons from mice’s frontal cortex, striatum, and hippocampus. As observed in Figure 1, the expression of A2AA3Hets in the striatum was significantly higher than that in the cortex or hippocampus; these results correlate with higher expression of the heteromer in the brain region with the highest expression of A2AR.

Figure 1.

Expression of A2AA3Hets in primary cultures of neurons isolated from the fetuses of pregnant C57BL/6J female mice. (A) A2AA3Hets were detected by the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) in primary cultures of striatal, hippocampal, and cortical neurons isolated from mouse fetuses. The negative control was obtained by omitting the primary antibody anti-A3R. Experiments were performed in samples from 6 different animals. (B) The number of red dots/cell was quantified using the Andy’s algorithm Fiji’s plug-in and represented versus the number of Hoechst-stained cell nuclei (blue). The number of red dots/cell was compared to those in neurons from different brain regions. The unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. Scale bar: 10 μm.

3.2. Characterization of the Functionality of A2AA3Hets in Primary Neurons from Three Brain Regions

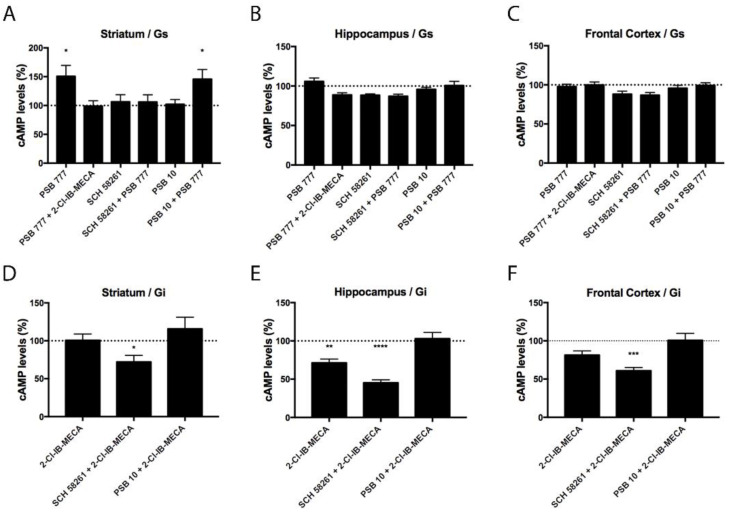

After demonstrating the differential expression of A2AA3Hets between the hippocampus, frontal cortex, and striatum, we were interested in checking whether the differential expression of the heteromer leads to differences in functionality. We have previously shown that the heteromeric context led to a marked decrease of the signaling originating at the A3R and that A2AR antagonists may overrode the blockade [9]. As the A2AR couples to Gs and the A3R couples to Gi, measurement of both increases in cAMP levels and decreases of forskolin-induced cAMP levels were undertaken. In primary neurons from the striatum, where there is a higher expression of A2AA3Hets, the A2AR agonist, PSB 777, increased the concentration of cytosolic cAMP. The increase was only blocked by the selective A2AR antagonist, SCH 58261. In the striatum, the selective A3R agonist, 2-Cl-IB-MECA, reduced the cytosolic cAMP levels induced by PSB 777 treatment. Neither in cortical nor in hippocampal neurons did agonists lead to significant increases in cAMP levels (Figure 2A–C).

Figure 2.

A2AA3Het-mediated Gs/Gi signaling in primary striatal, hippocampal, and cortical neurons from C57BL/6J mice. (A–F) Primary neurons were pre-treated with selective antagonists, 1 μM SCH 58261 -A2AR- or 1 μM PSB 10 -A3R-, and subsequently treated with the selective agonists, 100 nM PSB 777 -A2AR- or 100 nM 2-Cl-IB-MECA -A3R-. cAMP levels after 500 nM forskolin (FK) stimulation or vehicle treatment were detected by the Lance Ultra cAMP kit and results were expressed in % respect to basal levels (A–C) or in % respect to levels obtained upon FK stimulation (D–F). The values are the mean ± S.E.M. of 6 different experiments performed in triplicates. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-hoc test were used for statistical analysis. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001; versus basal levels (A–C) or versus FK treatment (D–F).

In primary striatal neurons treated with 0.5 μM forskolin (FK), the A3R agonist, 2-Cl-IB-MECA, was able to reduce cAMP levels only in the presence of the selective A2AR antagonist. This finding is consistent with previous results obtained in a heterologous expression system, namely, A3R activation does not lead to Gi engagement when the receptor is forming heteromers with A2AR. In contrast, the A3R agonist had an effect in hippocampal neurons, probably due to the expression of A3Rs not forming heteromers with A2AR. Still, the A2AR antagonist increased the effect of the A3R agonist. The results in neurons from the frontal cortex were similar, although the decrease induced by 2-Cl-IB-MECA was significant only in the presence of the A2AR antagonist (Figure 2D–F).

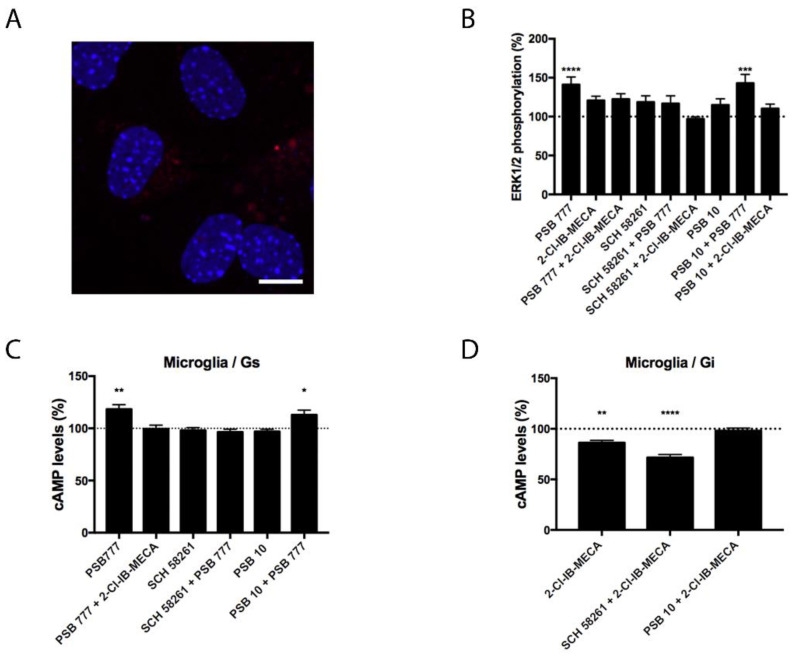

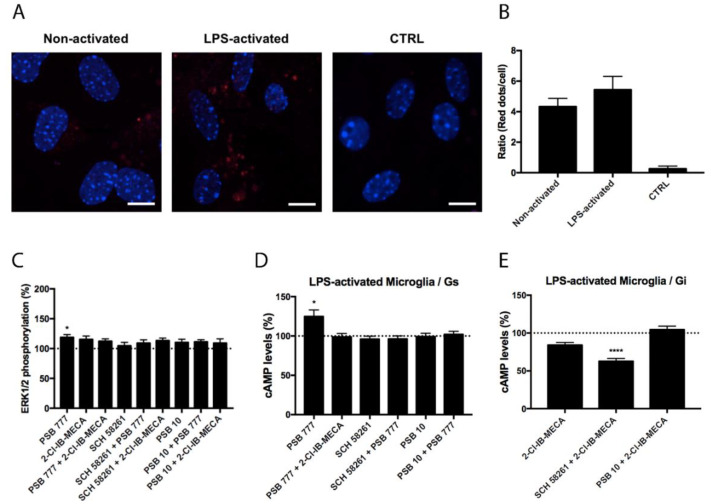

3.3. Characterization of the Functionality of A2AA3Hets in Primary Microglia

Experiments similar to those described in the previous section were performed in primary microglia from the total brain, resting or activated using LPS and IFN-γ. Although the expression of A2AA3Hets was similar in resting versus activated cells (Figure 3 and Figure 4), the functionality of Ado receptors differed. In resting cells, the A2AR agonist PSB 777, was able to increase the levels of the cyclic nucleotide. This effect was completely blocked by the presence of the A3R agonist, showing a negative cross-talk similar to that observed in primary striatal neurons. In cells treated with FK, the effect of 2-Cl-IB-MECA was noticeable and further increased by the A2AR antagonist (Figure 3). Similar results were obtained in experiments performed in activated microglia; the main difference was that the significance of 2-Cl-IB-MECA on decreasing the FK-induced cAMP levels (in activated cells) required the presence of the A2AR antagonist (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Expression and function of A2AA3Hets in primary cultures of microglia from C57BL/6J mice. (A) A2AA3Hets were detected in primary cultures of microglia by the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) using specific antibodies. Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Samples from 5 different animals were processed and analyzed. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B–D) Primary cultures of microglia from C57BL/6J mice were pre-treated with antagonists, 1 μM SCH 58261 -for A2AR- or 1 μM PSB 10 -for A3R-, subsequently stimulated with selective agonists, 100 nM PSB 777 -for A2AR- or 100 nM 2-Cl-IB-MECA -for A3R-, individually or in combination and treated with 500 nM forskolin (FK) or vehicle. (B) ERK1/2 phosphorylation was analyzed using an AlphaScreen® SureFire® kit (PerkinElmer) while cAMP levels were collected by the Lance Ultra cAMP kit and results were expressed in % respect to basal levels (B,C) or in % respect levels obtained upon 0.5 μM FK stimulation (D). Values are the mean ± S.E.M. of 10 different experiments performed in triplicates. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-hoc tests were used for statistical analysis. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001; versus basal (B,C) or versus FK treatment (D).

Figure 4.

Expression and function of A2AA3Hets in primary cultures of LPS-activated microglia from C57BL/6J mice. (A) A2AA3Hets were detected in primary cultures of non-activated and LPS-activated microglia by the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) using specific antibodies. The negative control was obtained by omitting the primary anti-A3R antibody. Experiments were performed in samples from 5 different animals. (B) The number of red dots/cell was quantified using the Andy’s algorithm Fiji’s plug-in and represented versus the number of Hoechst-stained cell nuclei (blue). The number of red dots/cell was compared between non-activated and LPS-activated microglia. The unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C–E) Primary cultures of LPS-activated microglia from C57BL/6J mice were pre-treated with antagonists, 1 μM SCH 58261 -for A2AR- or 1 μM PSB 10 -for A3R-, subsequently stimulated with selective agonists, 100 nM PSB 777 -for A2AR- or 100 nM 2-Cl-IB-MECA -for A3R-, individually or in combination and treated with 500 nM forskolin (FK) or vehicle. (C) ERK1/2 phosphorylation was analyzed using an AlphaScreen® SureFire® kit (PerkinElmer) while cAMP levels were collected by the Lance Ultra cAMP kit and results were expressed in % respect to basal levels (C,D) or in % respect to levels obtained upon 0.5 μM FK stimulation (E). Values are the mean ± S.E.M. of 6 different experiments performed in triplicates. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-hoc tests were used for statistical analysis. * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001; versus basal (C,D) or versus FK treatment (E).

Besides Gi or Gs coupling, the activation of Ado receptors leads to subsequent activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. To test the properties of the heteromer in the link to the MAPK signaling cascade, we measured ERK1/2 phosphorylation in resting and activated microglia. In activated cells, significant ERK1/2 phosphorylation was detected with the A2AR agonist; the effect did not increase when A3R agonist was also present (Figure 4). In resting cells, the A2AR agonist led to more robust ERK1/2 phosphorylation that was significantly blocked by the presence of the A3R agonist without any significant change in the presence of the A3R antagonist (Figure 3). Interestingly, the A3R agonist induced no effect in MAPK phosphorylation. Contrary to the data observed in the cAMP assays, the pretreatment with A2AR antagonists never potentiated this effect.

3.4. Expression and Functionality of the Heteromer in the APPSw,Ind Transgenic Mice Model of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

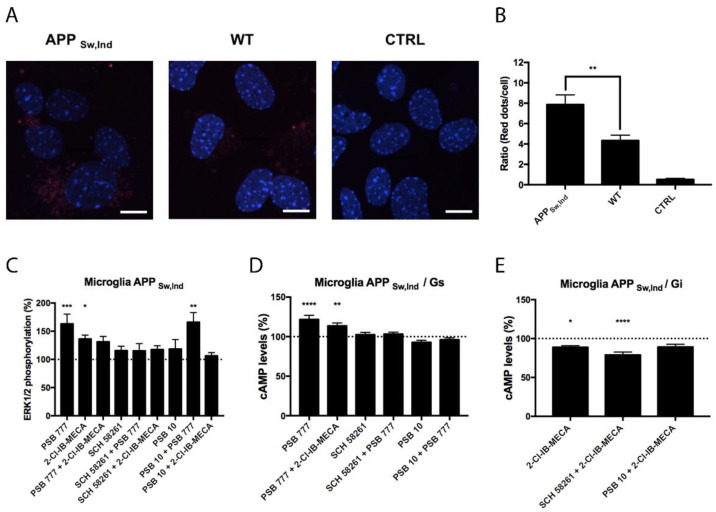

Microglial cells are important in neurodegenerative diseases coursing with neuroinflammation. For this reason, we compared the expression of A2AA3Hets in primary microglia from the brain of the APPSw,Ind transgenic AD model and of age-matched control mice. Figure 5A,B shows that the expression of the heteromer was increased by about two-fold in cells from the transgenic animal. Functionality was assessed in cells from the APPSw,Ind mice by measuring cAMP and pERK1/2 levels upon stimulation with agonists. The Gs coupling was confirmed when the A2AR agonist, PSB 777, was used. This effect was counteracted when cells were coactivated with the A3R agonist and PSB 777, showing a negative cross-talk, and also when preactivated with the A3R antagonist, showing cross-antagonism (Figure 5D), which was also found in activated cells from control mice (Figure 4D). Regarding Gi coupling, we found a significant effect of the A3R agonist, 2-Cl-IB-MECA, that was further enhanced by the A2AR antagonist, SCH 58261 (Figure 5E). The level of ERK1/2 phosphorylation was much higher when cells were treated with the A2AR agonist than when cells were treated with the A3R agonist. Costimulation led to a negative cross-talk, i.e., to a reduced signal when compared to the effect exerted by the A2AR agonist. Importantly, PSB 10 did not reduce the effect of the A2AR agonist, i.e., no cross-antagonism from A3R to A2AR was detected in these cells.

Figure 5.

Expression and function of A2AA3Hets in primary cultures of microglia from the APPSw,Ind mice model of Alzheimer’s disease. (A) A2AA3Hets were detected in primary cultures of APPSw,Ind microglia by the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) using specific antibodies. The negative control was obtained by omitting the primary anti-A3R antibody. Experiments were performed in samples from 12 different animals. (B) The number of red dots/cell was quantified using the Andy’s algorithm Fiji’s plug-in and represented versus the number of Hoechst-stained cell nuclei (blue). The number of red dots/cell was compared to those in microglia from wild type (WT) mice. The unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. ** p < 0.01, versus WT. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C–E) Primary cultures of microglia from APPSw,Ind mice were pre-treated with antagonists, 1 μM SCH 58261 -for A2AR- or 1 μM PSB 10 -for A3R-, and subsequently stimulated with selective agonists, 100 nM PSB 777 -for A2AR- or 100 nM 2-Cl-IB-MECA -for A3R-, individually or in combination. (C) ERK1/2 phosphorylation was analyzed using an AlphaScreen® SureFire® kit (PerkinElmer) while cAMP levels were collected by the Lance Ultra cAMP kit and results were expressed in % respect to basal levels (C,D) or in % respect levels obtained upon 0.5 μM FK stimulation (E). Values are the mean ± S.E.M. of 6 different experiments performed in triplicates. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-hoc tests were used for statistical analysis. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001; versus basal (C,D) or versus FK treatment (E).

4. Discussion

The results in this paper confirm a previous report showing that A2AR and A3R interact to form heteromeric complexes [9]. These complexes occur naturally and their expression in primary neurons correlates with the expression of A2AR in different brain regions. In fact, the expression of A2AA3Hets was much higher in neurons from the striatum than from the cortex or hippocampus (Figure 1).

There is interest in the potential of targeting A2ARs for combating a variety of diseases, especially after the success in launching istradefylline, a selective A2AR antagonist for adjuvant therapy of Parkinson’s disease. A2AR antagonists are also promising candidates to combat AD. In fact, work in transgenic animal models has shown neuroprotective activity and/or reversal of cognitive impairment [22,25,60,61,62,63,64]. Research on AD has focused mainly on neurons and this has revealed that extracellular deposits of amyloid and intraneuronal deposits of aberrantly phosphorylated tau protein are the two main pathological hallmarks of the disease. Antagonists of A2AR may afford neuroprotection by preventing the noxious actions of ß-amyloid peptide, as shown in cultured neurons and isolated nerve terminals [62,65]. Although A3R in the CNS has received less attention than other types of ARs, Stone suggested in 2002 that chronic administration of A3R agonists may provide neurons with protection against damage [66]. In summary, blocking A2AR or activating A3R in neurons seem to be neuroprotective in pathological scenarios. The discovery of A2AA3Hets and of the negative functional cross-talk [9] enables neuroprotection by A2AR antagonists targeting neurons expressing these heteromers. Indeed, within the heteromer, A2AR antagonists would block A2AR while making A3R respond to endogenous adenosine, i.e., exogenous A3R agonists would not be necessary to provide neuroprotection.

Neuroprotection—that is, addressing disease progression—may likely be achieved by targeting the glia that surround neurons whose survival is already significantly compromised. Microglia are attracting attention in the field of AD because microglial cells are involved in the inflammation that occurs in the brain of patients and because microglia could acquire a neuroprotective phenotype, generally known as M2 as opposed to M1 or pro-inflammatory; among the several GPCRs expressed in these cells, A2AR is an attractive target to regulate microglial activation and polarization [30,33,40,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77].

A2AR seems to have a residual role in resting microglia, but it becomes a main player in AD-related activated microglia, pointing to the A2AR expressed in these cells as an attractive target. Adenosine regulates microglial fate and activation [42,47,78,79,80], by unknown mechanisms and without details on the role of each AR type on cell polarization. The microglial A2AR regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation [45] and further data on the potential of these glial cells in the context of neurodegeneration and neuronal dysfunction was provided in 2016 by Cunha [75]. Despite the few reports on A3R and microglia, the receptor is expressed [44,81] in primary cultures and immortalized microglial cells; apart from its contribution to the MAPK signaling pathway [44], it mediates the inhibition of cell migration [54,82,83] and the production of TNFα [50].

In previous reports, we have shown that A2AR regulates nitric oxide production in cells activated with LPS and IFN-γ [39]. Moreover, A2AR is markedly upregulated in the cortical and hippocampal microglia of AD patients [26]. Therefore, it is relevant to consider how the interaction of A2AR with other cell surface proteins can affect its functionality in both healthy and pathological conditions. Previous reports have demonstrated in microglia that A2AR interacts with the cannabinoid CB2 receptor to form functional units in which cannabinoid signaling is compromised; however, the presence of A2AR antagonists leads to potentiation of cannabinoid signaling. These functional complexes are up-regulated in the APPSw,Ind AD transgenic mice model [33], thus reinforcing the view that A2AR antagonists may be useful in the therapy of AD. Additionally favoring the potential of A2AR antagonist in AD therapy is the reduced activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs), resulting from cross-antagonisms within macromolecular complexes formed by NMDA and A2A receptors in both neurons and microglia [32]. It should be noted that one of the current anti-AD treatments consists of reducing NMDAR function by using an allosteric negative modulator (memantine) [84].

Functional data in neurons and microglia are partly similar to those found in a heterologous system in which the two receptors are expressed and form A2AA3Hets. Hence, A3R-mediated signaling seems to be reduced/absent except in the presence of A2AR antagonists. Regarding A2AR-mediated signaling, we found that the use of the more selective agonist, PSB 777, leads to a reduced signal if compared to that reported using CGS 21680. At first sight, this is puzzling as PSB 777 is a very selective and full agonist of A2AR [85]; however, differential selectivity depending on the context may be the answer. The more robust signaling using CGS 21680 is not likely due to binding to A3R as the use of the selective A3R agonist, 2-Cl-IB-MECA, does not lead to significant responses either. This fact also suggests that PSB 777, in the experimental conditions and models used here, is not specially biased. In conclusion, it seems that PSB 777 is less potent than CGS 21680 in activating Gs-mediated signaling or in the link to the MAPK pathway cascade in microglia [9,33]. Functional selectivity in the form of biased agonism or else is dependent on the context of GPCR, especially if the receptor is part of a heteromer. Our results confirm that signaling via A2AR or A3R varies depending on the context, that is, on the structure of the heteromer and/or allosteric interactions with G and scaffold proteins [86,87]. Otherwise, it would be difficult to interpret why the signal is more robust in resting than in activated microglia although the expression of the heteromer is similar. Even assuming that part of the signaling is independent of A2AA3Het, the effect of PSB 777 should, theoretically, be higher in activated microglia where A2AR is upregulated.

In conclusion, it is important to note that A2AA3Het is upregulated in the APPSw,Ind AD model and that signaling through A2AR may depend on its interaction with other cell surface proteins and/or with proteins of the signaling machinery. In the primary microglia of the APPSw,Ind AD model, the functional selectivity is such that A2AR would increase Gi-mediated signaling of A3R. These findings reinforce the idea that A2AR antagonists deserve consideration to combat AD.

Acknowledgments

In memoriam, María Teresa Miras-Portugal a great scientist and a beloved friend of R.F.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.N. and R.F.; Data curation, R.F.; Formal analysis, A.L., J.L. and G.N.; Investigation, A.L., J.L., I.R. and C.P.-O.; Methodology, A.L., I.R. and G.N.; Resources, G.N. and R.F.; Supervision, G.N. and R.F.; Validation, G.N.; Writing—original draft, G.N. and R.F.; Writing—review & editing, A.L., J.L., I.R., C.P.-O., G.N. and R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the AARFD-17-503612 grant from the US Alzheimer’s Association, and by grants SAF2017-84117-R, RTI2018-094204-B-I00 and PID2020-113430RB-I00 funded by Spanish MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and, as appropriate, by “ERDF A way of making Europe”, by the “European Union” or by the “European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR”. The research group of the University of Barcelona is considered as a group of excellence (grup consolidat #2017 SGR 1497) by the Regional Catalonian Government, which does not provide any specific funding for reagents or for payment of services or Open Access fees).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Animal care and experimental procedures were in accordance with European and Spanish regulations (86/609/CEE; RD1201/2005).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alexander S.P., Christopoulos A., Davenport A.P., Kelly E., Mathie A., Peters J.A., Veale E.L., Armstrong J.F., Faccenda E., Harding S.D., et al. The Concise Guide To Pharmacology 2021/22: G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021;178:S27–S156. doi: 10.1111/bph.15538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gines S., Hillion J., Torvinen M., Le Crom S., Casado V., Canela E.I., Rondin S., Lew J.Y., Watson S., Zoli M., et al. Dopamine D1 and Adenosine A1 Receptors form Functionally Interacting Heteromeric Complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8606–8611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150241097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillion J., Canals M., Torvinen M., Casado V., Scott R., Terasmaa A., Hansson A., Watson S., Olah M.E., Mallol J., et al. Coaggregation, Cointernalization, and Codesensitization of Adenosine A2A Receptors and Dopamine D2 Receptors. [(accessed on 21 March 2015)];J. Biol. Chem. 2002 277:18091–18097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107731200. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11872740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciruela F., Casadó V., Rodrigues R., Luján R., Burgueño J., Canals M., Borycz J., Rebola N., Goldberg S., Mallol J., et al. Presynaptic Control of Striatal Glutamatergic Neurotransmission by Adenosine A1-A2A Receptor Heteromers. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2080–2087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3574-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarro G., Cordomí A., Brugarolas M., Moreno E., Aguinaga D., Pérez-Benito L., Ferre S., Cortés A., Casadó V., Mallol J., et al. Cross-Communication between Gi and Gs in a G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Heterotetramer Guided by a Receptor C-Terminal Domain. BMC Biol. 2018;16:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12915-018-0491-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarro G., Cordomí A., Zelman-Femiak M., Brugarolas M., Moreno E., Aguinaga D., Perez-Benito L., Cortés A., Casadó V., Mallol J., et al. Quaternary Structure of a G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Heterotetramer in Complex with Gi and Gs. BMC Biol. 2016;14:26. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gnad T., Navarro G., Lahesmaa M., Reverte-Salisa L., Copperi F., Cordomi A., Naumann J., Hochhäuser A., Haufs-Brusberg S., Wenzel D., et al. Adenosine/A2B Receptor Signaling Ameliorates the Effects of Aging and Counteracts Obesity. [(accessed on 9 July 2020)];Cell Metab. 2020 32:56–70.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.006. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32589947/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinz S., Navarro G., Borroto-Escuela D., Seibt B.F., Ammon C., De Filippo E., Danish A., Lacher S.K., Červinková B., Rafehi M., et al. Adenosine A2A Receptor Ligand Recognition and Signaling Is Blocked by A2B Receptors. [(accessed on 5 April 2018)];Oncotarget. 2018 9:13593–13611. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24423. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29568380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lillo A., Martínez-Pinilla E., Reyes-Resina I., Navarro G., Franco R. Adenosine A2a and A3 Receptors Are Able to Interact with Each Other. A Further Piece in the Puzzle of Adenosine Receptor-Mediated Signaling. [(accessed on 29 July 2020)];Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020 21:5070. doi: 10.3390/ijms21145070. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/14/5070?utm_source=researcher_app&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=RESR_MRKT_Researcher_inbound. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenner P. An Overview of Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonists in Parkinson’s Disease. [(accessed on 23 October 2017)];Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2014 119:71–86. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801022-8.00003-9. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25175961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenner P., Mori A., Hauser R., Morelli M., Fredholm B.B., Chen J.F. Adenosine, Adenosine A 2A Antagonists, and Parkinson’s Disease. [(accessed on 25 June 2015)];Park. Relat. Disord. 2009 15:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.12.006. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19446490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saki M., Yamada K., Koshimura E., Sasaki K., Kanda T. In Vitro Pharmacological Profile of the A2A Receptor Antagonist Istradefylline. [(accessed on 27 December 2017)];Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2013 386:963–972. doi: 10.1007/s00210-013-0897-5. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23812646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo T., Mizuno Y., Japanese Istradefylline Study Group A Long-Term Study of Istradefylline Safety and Efficacy in Patients with Parkinson Disease. [(accessed on 17 March 2015)];Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2015 38:41–46. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000073. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25768849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno Y., Kondo T. Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonist Istradefylline Reduces Daily OFF Time in Parkinson’s Disease. [(accessed on 23 October 2017)];Mov. Disord. 2013 28:1138–1141. doi: 10.1002/mds.25418. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23483627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger A.A., Winnick A., Welschmeyer A., Kaneb A., Berardino K., Cornett E.M., Kaye A.D., Viswanath O., Urits I. Istradefylline to Treat Patients with Parkinson’s Disease Experiencing “Off” Episodes: A Comprehensive Review. [(accessed on 14 October 2021)];Neurol. Int. 2020 12:109–129. doi: 10.3390/neurolint12030017. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33302331/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatfield S.M., Sitkovsky M. A2A Adenosine Receptor Antagonists to Weaken the Hypoxia-HIF-1α Driven Immunosuppression and Improve Immunotherapies of Cancer. [(accessed on 24 October 2017)];Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016 29:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2016.06.009. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27429212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popoli P., Blum D., Domenici M.R., Burnouf S., Chern Y. A Critical Evaluation of Adenosine A2A Receptors as Potentially “Druggable” Targets in Huntington’s Disease. [(accessed on 19 December 2017)];Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008 14:1500–1511. doi: 10.2174/138161208784480117. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18537673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J.-F., Sonsalla P.K., Pedata F., Melani A., Domenici M.R., Popoli P., Geiger J., Lopes L.V., de Mendonça A. Adenosine A2A Receptors and Brain Injury: Broad Spectrum of Neuroprotection, Multifaceted Actions and “Fine Tuning” Modulation. [(accessed on 23 October 2017)];Prog. Neurobiol. 2007 83:310–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.09.002. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18023959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orru M., Bakešová J., Brugarolas M., Quiroz C., Beaumont V., Goldberg S.R., Lluís C., Cortés A., Franco R., Casadó V., et al. Striatal Pre- and Postsynaptic Profile of Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonists. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee C., Chern Y. Adenosine Receptors and Huntington’s Disease. [(accessed on 19 December 2017)];Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2014 119:195–232. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801022-8.00010-6. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128010228000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W., Silva H.B., Real J., Wang Y.-M., Rial D., Li P., Payen M.-P., Zhou Y., Muller C.E., Tomé A.R., et al. Inactivation of Adenosine A2A Receptors Reverses Working Memory Deficits at Early Stages of Huntington’s Disease Models. [(accessed on 19 December 2017)];Neurobiol. Dis. 2015 79:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.03.030. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25892655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li P., Rial D., Canas P.M., Yoo J.H., Li W., Zhou X., Wang Y., Van Westen G.J.P., Payen M.P., Augusto E., et al. Optogenetic Activation of Intracellular Adenosine A2A Receptor Signaling in the Hippocampus is Sufficient to Trigger CREB Phosphorylation and Impair Memory. [(accessed on 9 March 2018)];Mol. Psychiatry. 2015 20:1339–1349. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.182. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25687775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyebji S., Saavedra A., Canas P.M., Pliassova A., Delgado-García J.M., Alberch J., Cunha R.A., Gruart A., Pérez-Navarro E. Hyperactivation of D1 and A2A Receptors Contributes to Cognitive Dysfunction in Huntington’s Disease. [(accessed on 19 December 2017)];Neurobiol. Dis. 2015 74:41–57. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.11.004. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0969996114003428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu F.-L.L., Lin J.-T.T., Chuang C.-Y.Y., Chien T., Chen C.-M.M., Chen K.-H.H., Hsiao H.-Y.Y., Lin Y.-S.S., Chern Y., Kuo H.-C.C. Elucidating the Role of the A2A Adenosine Receptor in Neurodegeneration Using Neurons Derived from Huntington’s Disease iPSCs. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:6066–6079. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J.-F. Adenosine Receptor Control of Cognition in Normal and Disease. [(accessed on 18 February 2016)];Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2014 119:257–307. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801022-8.00012-X. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25175970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angulo E., Casadó V., Mallol J., Canela E.I., Viñals F., Ferrer I., Lluis C., Franco R. A1 Adenosine Receptors Accumulate in Neurodegenerative Structures in Alzheimer Disease and Mediate both Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing and Tau Phosphorylation and Translocation. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:440–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banik A., Brown R.E., Bamburg J., Lahiri D.K., Khurana D., Friedland R.P., Chen W., Ding Y., Mudher A., Padjen A.L., et al. Translation of Pre-Clinical Studies into Successful Clinical Trials for Alzheimer’s Disease: What Are the Roadblocks and How Can They Be Overcome? J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:815–843. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nisticò R., Pignatelli M., Piccinin S., Mercuri N.B., Collingridge G. Targeting Synaptic Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. [(accessed on 20 December 2017)];Mol. Neurobiol. 2012 46:572–587. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8324-3. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22914888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franco R., Cedazo-Minguez A. Successful Therapies for Alzheimer’s Disease: Why so Many in Animal Models and None in Humans? [(accessed on 15 January 2022)];Front. Pharmacol. 2014 5:146. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00146. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25009496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franco R., Navarro G. Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonists in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Huge Potential and Huge Challenges. [(accessed on 13 September 2020)];Front. Psychiatry. 2018 9:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00068. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29593579/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navarro G., Morales P., Rodríguez-Cueto C., Fernández-Ruiz J., Jagerovic N., Franco R. Targeting Cannabinoid CB2 Receptors in the Central Nervous System. Medicinal Chemistry Approaches with Focus on Neurodegenerative Disorders. [(accessed on 7 December 2016)];Front. Neurosci. 2016 10:406. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00406. Available online: www.uniprot.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franco R., Rivas-Santisteban R., Casanovas M., Lillo A., Saura C.A., Navarro G. Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonists Affects NMDA Glutamate Receptor Function. Potential to Address Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease. [(accessed on 31 March 2021)];Cells. 2020 9:1075. doi: 10.3390/cells9051075. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32357548/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franco R., Reyes-Resina I., Aguinaga D., Lillo A., Jiménez J., Raïch I., Borroto-Escuela D.O., Ferreiro-Vera C., Canela E.I., Sánchez de Medina V., et al. Potentiation of Cannabinoid Signaling in Microglia by Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonists. Glia. 2019;67:2410–2423. doi: 10.1002/glia.23694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chhor V., Le Charpentier T., Lebon S., Oré M.-V., Celador I.L., Josserand J., Degos V., Jacotot E., Hagberg H., Sävman K., et al. Characterization of Phenotype Markers and Neuronotoxic Potential of Polarised Primary Microglia In Vitro. [(accessed on 17 November 2014)];Brain. Behav. Immun. 2013 32:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.02.005. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S088915911300127X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franco R., Fernández-Suárez D. Alternatively Activated Microglia and Macrophages in the Central Nervous System. [(accessed on 14 June 2015)];Prog. Neurobiol. 2015 131:65–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.05.003. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26067058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinhal-Enfield G., Ramanathan M., Hasko G., Vogel S.N., Salzman A.L., Boons G.-J., Leibovich S.J. An Angiogenic Switch in Macrophages Involving Synergy between Toll-Like Receptors 2, 4, 7, and 9 and Adenosine A(2A) Receptors. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;163:711–721. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63698-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrante C.J., Pinhal-Enfield G., Elson G., Cronstein B.N., Hasko G., Outram S., Leibovich S.J. The Adenosine-Dependent Angiogenic Switch of Macrophages to an M2-Like Phenotype Is Independent of Interleukin-4 Receptor Alpha (IL-4Rα) Signaling. [(accessed on 1 October 2014)];Inflammation. 2013 36:921–931. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9621-3. Available online: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3710311&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrante C.J., Leibovich S.J. Regulation of Macrophage Polarization and Wound Healing. [(accessed on 9 October 2014)];Adv. Wound Care. 2012 1:10–16. doi: 10.1089/wound.2011.0307. Available online: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3623587&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saura J., Angulo E., Ejarque A., Casado V., Tusell J.M., Moratalla R., Chen J.-F.F., Schwarzschild M.A., Lluis C., Franco R., et al. Adenosine A2A Receptor Stimulation Potentiates Nitric Oxide Release by Activated Microglia. [(accessed on 20 March 2015)];J. Neurochem. 2005 95:919–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03395.x. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16092928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haque M.E., Kim I.S., Jakaria M., Akther M., Choi D.K. Importance of GPCR-Mediated Microglial Activation in Alzheimer’s Disease. [(accessed on 14 October 2021)];Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018 12:258. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00258. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30186116/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferreira-Silva J., Aires I.D., Boia R., Ambrósio A.F., Santiago A.R. Activation of Adenosine A3 Receptor Inhibits Microglia Reactivity Elicited by Elevated Pressure. [(accessed on 14 October 2021)];Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020 21:7218. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197218. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33007835/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogata T., Schubert P. Programmed Cell Death in Rat Microglia Is Controlled by Extracellular Adenosine. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];Neurosci. Lett. 1996 218:91–94. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(96)13118-9. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8945735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Putten C., Zuiderwijk-Sick E.A., van Straalen L., de Geus E.D., Boven L.A., Kondova I., IJzerman A.P., Bajramovic J.J. Differential Expression of Adenosine A3 Receptors Controls Adenosine A2A Receptor-Mediated Inhibition of TLR Responses in Microglia. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];J. Immunol. 2009 182:7603–7612. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803383. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19494284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammarberg C., Schulte G., Fredholm B.B. Evidence for Functional Adenosine A3 Receptors in Microglia Cells. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];J. Neurochem. 2003 86:1051–1054. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01919.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12887702/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gyoneva S., Davalos D., Biswas D., Swanger S.A., Garnier-Amblard E., Loth F., Akassoglou K., Traynelis S.F. Systemic Inflammation Regulates Microglial Responses to Tissue Damage In Vivo. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];Glia. 2014 62:1345–1360. doi: 10.1002/glia.22686. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24807189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merighi S., Borea P.A., Stefanelli A., Bencivenni S., Castillo C.A., Varani K., Gessi S. A2a and A2b Adenosine Receptors Affect HIF-1α Signaling in Activated Primary Microglial Cells. [(accessed on 25 March 2019)];Glia. 2015 63:1933–1952. doi: 10.1002/glia.22861. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gyoneva S., Orr A.G., Traynelis S.F. Differential Regulation of Microglial Motility by ATP/ADP and Adenosine. [(accessed on 21 March 2015)];Park. Relat. Disord. 2009 15((Suppl. S3)):S195–S199. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70813-2. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20082989/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rebola N., Simões A.P., Canas P.M., Tomé A.R., Andrade G.M., Barry C.E., Agostinho P.M., Lynch M.A., Cunha R.A. Adenosine A2A Receptors Control Neuroinflammation and Consequent Hippocampal Neuronal Dysfunction. [(accessed on 20 March 2020)];J. Neurochem. 2011 117:100–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07178.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21235574/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aires I.D., Boia R., Rodrigues-Neves A.C., Madeira M.H., Marques C., Ambrósio A.F., Santiago A.R. Blockade of Microglial Adenosine A2A Receptor Suppresses Elevated Pressure-Induced Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Cell Death in Retinal Cells. Glia. 2019;67:896–914. doi: 10.1002/glia.23579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee J.Y., Jhun B.S., Oh Y.T., Lee J.H., Choe W., Baik H.H., Ha J., Yoon K.-S., Kim S.S., Kang I. Activation of Adenosine A3 Receptor Suppresses Lipopolysaccharide-Induced TNF-α Production through Inhibition of PI 3-Kinase/Akt and NF-κB Activation in Murine BV2 Microglial Cells. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];Neurosci. Lett. 2006 396:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.11.004. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16324785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santiago A.R., Baptista F.I., Santos P.F., Cristóvão G., Ambrósio A.F., Cunha R.A., Gomes C.A., Pintor J. Role of Microglia Adenosine A2A Receptors in Retinal and Brain Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014;2014:465694. doi: 10.1155/2014/465694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boia R., Elvas F., Madeira M.H., Aires I.D., Rodrigues-Neves A.C., Tralhão P., Szabó E.C., Baqi Y., Müller C.E., Tomé Â.R., et al. Treatment with A2A Receptor Antagonist KW6002 and Caffeine Intake Regulate Microglia Reactivity and Protect Retina against Transient Ischemic Damage. [(accessed on 30 December 2017)];Cell Death Dis. 2017 8:e3065. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.451. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28981089/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gyoneva S., Shapiro L., Lazo C., Garnier-Amblard E., Smith Y., Miller G.W., Traynelis S.F. Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonism Reverses Inflammation-Induced Impairment of Microglial Process Extension in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. [(accessed on 12 March 2015)];Neurobiol. Dis. 2014 67:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.03.004. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24632419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi I.-Y., Lee J.-C., Ju C., Hwang S., Cho G.-S., Lee H.W., Choi W.J., Jeong L.S., Kim W.-K. A3 Adenosine Receptor Agonist Reduces Brain Ischemic Injury and Inhibits Inflammatory Cell Migration in Rats. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;179:2042–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Illes P., Rubini P., Ulrich H., Zhao Y., Tang Y. Regulation of Microglial Functions by Purinergic Mechanisms in the Healthy and Diseased CNS. [(accessed on 11 March 2021)];Cells. 2020 9:1108. doi: 10.3390/cells9051108. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/9/5/1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohsawa K., Sanagi T., Nakamura Y., Suzuki E., Inoue K., Kohsaka S. Adenosine A3 Receptor Is Involved in ADP-Induced Microglial Process Extension and Migration. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];J. Neurochem. 2012 121:217–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07693.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22335470/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terayama R., Tabata M., Maruhama K., Iida S. A 3 Adenosine Receptor Agonist Attenuates Neuropathic Pain by Suppressing Activation of Microglia and Convergence of Nociceptive Inputs in the Spinal Dorsal Horn. [(accessed on 14 October 2021)];Exp. Brain Res. 2018 236:3203–3213. doi: 10.1007/s00221-018-5377-1. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30206669/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mucke L., Masliah E., Yu G.Q., Mallory M., Rockenstein E.M., Tatsuno G., Hu K., Kholodenko D., Johnson-Wood K., McConlogue L. High-Level Neuronal Expression of Abeta 1-42 in Wild-Type Human Amyloid Protein Precursor Transgenic Mice: Synaptotoxicity without Plaque Formation. [(accessed on 31 July 2017)];J. Neurosci. 2000 20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10818140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hradsky J., Raghuram V., Reddy P.P., Navarro G., Hupe M., Casado V., McCormick P.J., Sharma Y., Kreutz M.R., Mikhaylova M. Post-Translational Membrane Insertion of Tail-Anchored Transmembrane EF-Hand Ca2+Sensor Calneurons Requires the TRC40/Asna1 Protein Chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:36762–36776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silva A.C., Lemos C., Gonçalves F.Q., Pliássova A.V., Machado N.J., Silva H.B., Canas P.M., Cunha R.A., Lopes J.P., Agostinho P. Blockade of Adenosine A2A Receptors Recovers Early Deficits of Memory and Plasticity in the Triple Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. [(accessed on 9 March 2020)];Neurobiol. Dis. 2018 117:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.05.024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29859867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gonçalves F.Q., Lopes J.P., Silva H.B., Lemos C., Silva A.C., Gonçalves N., Tomé Â.R., Ferreira S.G., Canas P.M., Rial D., et al. Synaptic and Memory Dysfunction in a β-Amyloid Model of Early Alzheimer’s Disease Depends on Increased Formation of ATP-Derived Extracellular Adenosine. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019;132:104570. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Canas P.M., Porciuncula L.O., Cunha G.M.A., Silva C.G., Machado N.J., Oliveira J.M.A., Oliveira C.R., Cunha R.A. Adenosine A2A Receptor Blockade Prevents Synaptotoxicity and Memory Dysfunction Caused by -Amyloid Peptides via p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14741–14751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3728-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Da Silva S.V., Haberl M.G., Zhang P., Bethge P., Lemos C., Gonçalves N., Gorlewicz A., Malezieux M., Gonçalves F.Q., Grosjean N., et al. Early Synaptic Deficits in the APP/PS1 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Involve Neuronal Adenosine A2A Receptors. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11915. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Temido-Ferreira M., Ferreira D.G., Batalha V.L., Marques-Morgado I., Coelho J.E., Pereira P., Gomes R., Pinto A., Carvalho S., Canas P.M., et al. Age-Related Shift in LTD Is Dependent on Neuronal Adenosine A2A Receptors Interplay with mGluR5 and NMDA Receptors. Mol. Psychiatry. 2020;25:1876–1900. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0110-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dall’lgna O.P., Porciúncula L.O., Souza D.O., Cunha R.A., Lara D.R. Neuroprotection by Caffeine and Adenosine A2A Receptor Blockade of Beta-Amyloid Neurotoxicity. [(accessed on 3 January 2022)];Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003 138:1207–1209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705185. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12711619/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stone T.W. Purines and Neuroprotection. [(accessed on 3 January 2022)];Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2002 513:249–280. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0123-7_9. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12575824/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ashton J.C., Glass M. The Cannabinoid CB2 Receptor as a Target for Inflammation-Dependent Neurodegeneration. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2007;5:73–80. doi: 10.2174/157015907780866884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colton C.A., Mott R.T., Sharpe H., Xu Q., Van Nostrand W.E., Vitek M.P. Expression Profiles for Macrophage Alternative Activation Genes in AD and in Mouse Models of AD. [(accessed on 16 October 2014)];J. Neuroinflamm. 2006 3:27. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-27. Available online: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1609108&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gyoneva S., Swanger S.A., Zhang J., Weinshenker D., Traynelis S.F. Altered Motility of Plaque-Associated Microglia in a Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. [(accessed on 4 March 2019)];Neuroscience. 2016 330:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.05.061. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0306452216302202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fiebich B.L., Biber K., Lieb K., van Calker D., Berger M., Bauer J., Gebicke-Haerter P.J. Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression in Rat Microglia Is Induced by Adenosine A2a-Receptors. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];Glia. 1996 18:152–180. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199610)18:2<152::AID-GLIA7>3.0.CO;2-2. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8913778/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cassano T., Calcagnini S., Pace L., De Marco F., Romano A., Gaetani S. Cannabinoid Receptor 2 Signaling in Neurodegenerative Disorders: From Pathogenesis to a Promising Therapeutic Target. Front. Neurosci. 2017;11:30. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Michelucci A., Heurtaux T., Grandbarbe L., Morga E., Heuschling P. Characterization of the Microglial Phenotype under Specific Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Conditions: Effects of Oligomeric and Fibrillar Amyloid-Beta. [(accessed on 18 October 2014)];J. Neuroimmunol. 2009 210:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.02.003. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19269040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ni R., Mu L., Ametamey S. Positron Emission Tomography of Type 2 Cannabinoid Receptors for Detecting Inflammation in the Central Nervous System. [(accessed on 26 June 2018)];Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2019 40:351–357. doi: 10.1038/s41401-018-0035-5. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41401-018-0035-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhat S.A., Goel R., Shukla S., Shukla R., Hanif K. Angiotensin Receptor Blockade by Inhibiting Glial Activation Promotes Hippocampal Neurogenesis Via Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Hypertension. [(accessed on 4 October 2019)];Mol. Neurobiol. 2018 55:5282–5298. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0754-5. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28884281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cunha R.A. How Does Adenosine Control Neuronal Dysfunction and Neurodegeneration? [(accessed on 11 September 2018)];J. Neurochem. 2016 139:1019–1055. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13724. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27365148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bronzuoli M.R., Iacomino A., Steardo L., Scuderi C. Targeting Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Inflamm. Res. 2016;9:199–208. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S86958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Muzio L., Viotti A., Martino G. Microglia in Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration: From Understanding to Therapy. [(accessed on 15 October 2021)];Front. Neurosci. 2021 15:742065. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.742065. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34630027/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rodrigues-Neves A.C., Aires I.D., Vindeirinho J., Boia R., Madeira M.H., Gonçalves F.Q., Cunha R.A., Santos P.F., Ambrósio A.F., Santiago A.R. Elevated Pressure Changes the Purinergic System of Microglial Cells. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];Front. Pharmacol. 2018 9:16. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00016. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29416510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koizumi S., Ohsawa K., Inoue K., Kohsaka S. Purinergic Receptors in Microglia: Functional Modal Shifts of Microglia Mediated by P2 and P1 Receptors. Glia. 2013;61:47–54. doi: 10.1002/glia.22358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rathbone M.P., Middlemiss P.J., Gysbers J.W., Andrew C., Herman M.A.R., Reed J.K., Ciccarelli R., Di Iorio P., Caciagli F. Trophic Effects of Purines in Neurons and Glial Cells. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];Prog. Neurobiol. 1999 59:663–690. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00017-9. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10845757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Von Lubitz D.K., Simpson K.L., Lin R.C. Right Thing at a Wrong Time? Adenosine A3 Receptors and Cerebroprotection in Stroke. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001 939:85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03615.x. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11462807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hwang S., Cho G.-S., Ryu S., Kim H.J., Song H.Y., Yune T.Y., Ju C., Kim W.-K. Post-Ischemic Treatment of WIB801C, Standardized Cordyceps Extract, Reduces Cerebral Ischemic Injury via Inhibition of Inflammatory Cell Migration. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016 186:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.03.052. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27036628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ryu S., Kwon J., Park H., Choi I.-Y., Hwang S., Gajulapati V., Lee J.Y., Choi Y., Varani K., Borea P.A., et al. Amelioration of Cerebral Ischemic Injury by a Synthetic Seco-nucleoside LMT497. [(accessed on 3 September 2018)];Exp. Neurobiol. 2015 24:31. doi: 10.5607/en.2015.24.1.31. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25792868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lipton S. Pathologically-Activated Therapeutics for Neuroprotection: Mechanism of NMDA Receptor Block by Memantine and S-Nitrosylation. Curr. Drug Targets. 2007;8:621–632. doi: 10.2174/138945007780618472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.El-Tayeb A., Michael S., Abdelrahman A., Behrenswerth A., Gollos S., Nieber K., Müller C.E. Development of Polar Adenosine A 2A Receptor Agonists for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Synergism with A 2B Antagonists. [(accessed on 17 October 2021)];ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011 2:890–895. doi: 10.1021/ml200189u. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24900277/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Franco R., Rivas-Santisteban R., Reyes-Resina I., Navarro G. The Old and New Visions of Biased Agonism through the Prism of Adenosine Receptor Signaling and Receptor/Receptor and Receptor/Protein Interactions. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;11:628601. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.628601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Franco R., Aguinaga D., Jiménez J., Lillo J., Martínez-Pinilla E., Navarro G. Biased Receptor Functionality versus Biased Agonism in G-Protein-Coupled Receptors. [(accessed on 26 July 2019)];Biomol. Concepts. 2018 9:143–154. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2018-0013. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30864350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to corresponding authors.