Abstract

Between January and April 1998, a meningitis outbreak due to serogroup A meningococcus took place in Senegal. The outbreak began in Gandiaye, 165 km to the east of Dakar, and progressed towards the towns of Gossas, Niakkhar, Guinguineo, Fatik, Foundiougne, Dioffior, Sokone, Kaolack, and Nioro. At the same time, the outbreak reached regions of Kaffrine, Koungheul, and Tambacounda in the east of Senegal. A total of 1,350 cases and 200 deaths were reported. The WHO Collaborating Center in Marseilles received 24 strains for analysis. All were serogroup A Neisseria meningitidis, type 4 and subtype P1.9. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, performed by Institut Pasteur Paris, showed that the strains belonged to clone III-1. DNA restriction fragments generated by endonuclease BglII and analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis showed 24 indistinguishable fingerprint patterns similar to those of meningococcus strains isolated from African outbreaks since 1988. Three strains were studied by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) with seven loci. The comparison between sequences and existing alleles on the MLST website (http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk) allowed us to assign these strains to sequence type 5 (ST5), as their sequences were identical to the consensus at seven loci. All 24 strains were susceptible to penicillin, amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, and rifampin. Subgroup III is finishing its spread towards west of the meningitis belt of Africa. To our knowledge, this is the first time subgroup III, and more precisely ST5, strains are reported as being responsible for a meningitis outbreak in Senegal.

In the meningitis belt of Africa, epidemics of meningococcal meningitis occur periodically and are mainly caused by serogroup A Neisseria meningitidis (5, 6, 21, 25). Through the application of molecular methods and especially multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE), it has been possible to identify and monitor the spread of hypervirulent clones all over the world (3, 20). Using this method and the electrophoretic variation of 15 cytoplasmic allozymes and four outer membrane proteins, Wang et al. classified 290 serogroup A N. meningitidis strains into 84 electrophoretic types and 9 subgroups (23). Serogroup A strains of subgroup III were associated with a pandemic that started in China in the mid-1960s and spread to Russia, Scandinavia, and Brazil (15, 23). In the early 1980s, a second wave of meningococcal disease caused by subgroup III started in China. That pandemic reached Nepal, probably India, and then Saudi Arabia in 1987 (11). In 1988, epidemics caused by subgroup III started in Africa (Chad and Sudan) (11, 19) and reached most African countries by 1998 (3). Rather than comparing the electrophoretic mobilities of enzymes, in 1998, Maiden et al. described multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (7), a new method involving the sequencing of seven housekeeping genes. The comparison between sequences and alleles on the MLST website allows the determination of the allele for each locus. The allele combination at seven loci characterizes the sequence type (ST) of the strain. Like MLEE, MLST identifies the major meningococcal lineages associated with invasive diseases (7). Since the results of MLST are unambiguous, reliable, and easily transferable between laboratories, for epidemiological purposes, MLST will probably be the reference method for N. meningitidis typing in the future.

A meningitis outbreak due to serogroup A meningococcus started in January 1998 in Senegal. The first cases were noted in Gandiaye, 165 km to the east of Dakar, and meningitis progressed towards the towns of Gossas, Niakkhar, Guinguineo, Fatik, Foundiougne, Dioffior, Sokone, Kaolack, and Nioro. At the same time, the outbreak reached regions of Kaffrine, Koungheul, and Tambacounda in the east of Senegal. The outbreak ended in April. Between January and April, 1,350 cases and 200 deaths were noted (2).

In this work, we report the results of the characterization of 24 N. meningitidis strains, isolated during a 1998 Senegal outbreak, to determine if they belong to subgroup III. We also used MLST to determine the ST of these strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Epidemiological data.

The epidemiological data of the 1998 Senegal outbreak have been described in reference 2.

Bacterial strains.

During this outbreak, 24 strains were isolated from cerebrospinal fluids of 24 patients living in different towns affected by the outbreak. All these strains were sent to the Unité du Méningocoque, WHO Collaborating Center in Marseilles (France), for analysis and stored at −80°C in brain heart broth with 15% glycerol. Each strain was given an identification number, Mrs 98029 to Mrs 98052. Bacterial identification was carried out by Gram staining, oxidase tests, and tests for biochemical characteristics by using a ready-for-use kit (Neisseria 4H; Sanofi Pasteur, Paris, France). N. meningitidis strains were serogrouped by agglutination with sera manufactured at the Institut de Médecine Tropicale du Service de Santé des Armées (Marseilles). Serotypes and subtypes were determined by using the monoclonal kit from the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (Bilthoven, The Netherlands) and the whole-cell enzyme immunoassay technique described elsewhere (1, 4, 16).

MLEE.

MLEE was performed at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. Methods of protein extract preparation, starch gel electrophoresis, and selective enzyme staining were similar to those described by Selander et al. (20). The 13 enzymes assayed were malic enzyme, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, peptidase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, aconitase, NADP-linked glutamate dehydrogenase, NAD-linked glutamate dehydrogenase, fumarase, alkaline phosphatase, two indophenol oxidases, and adenylate kinase. Each isolate was characterized by its allele combination at 13 enzyme loci, and multilocus genotypes were compared with those of a reference serogroup A strain (see Table 2) (17).

TABLE 2.

MLST allele profile at seven loci of three strains isolated from a 1998 Senegal outbreak (Mrs strains) and two reference strains representative of ST5

| Strains | Allele at indicated locus

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abcZ | adk | aroE | fumC | gdh | pdhC | pgm | |

| Mrs 98029, Mrs 98040, Mrs 98046 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Chad 1988 (F6124), Saudi Arabia 1987 (F4698) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

PFGE.

Comparison of whole chromosomal DNA was performed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of macrorestriction fragments generated by endonuclease BglII (13). Agar plugs containing bacteria were treated with lysozyme, proteinase K, and then Pefabloc (Roche, Meylan, France). Plugs were incubated with 25 U of the endonuclease BglII (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) overnight at 37°C. Electrophoresis was performed with a CHEF Mapper (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA at 14°C, and a voltage of 4.5 V/cm was applied with pulse-time ramping from 30 s to 1 s over 22 h. Then a pulse of 0.1 to 1 s was applied for 2 h 30 min with a voltage of 6 V/cm.

MLST.

The primers of the housekeeping genes abcZ (putative ABC transporter), adk (adenylate kinase), aroE (shikimate dehydrogenase), gdh (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase), pdhC (pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit), and pgm (phosphoglucomutase) were synthesized by our institute according to the sequences published by Maiden et al. (7). A seventh locus, fumC (fumarase), was added. Primers for amplification and for sequencing of fumC fragment were synthesized from the sequences given on the MLST website (http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk). After DNA preparation and amplification by PCR, analysis of each locus sequence was carried out on an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems). The sequence alignment was performed on the Sequence Navigator software (PE Applied Biosystems). The sequences were then compared to the different existing alleles registered on the MLST website.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing of the N. meningitidis strains.

MICs were determined by using E-test strips carrying rifampin, penicillin, chloramphenicol, or amoxicillin (bmd, Solna, Sweden). Mueller-Hinton agar plates (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) were inoculated by swabbing the surface in three directions with standardized inocula (0.5 McFarland). Agar plates were then incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. After 24 h, MICs were read from the scale at the intersection of the growth inhibition zone with the strip (14).

RESULTS

Strain characterization.

All 24 strains were gram-negative diplococci, oxidase positive and catalase positive. They were identified as N. meningitidis on the basis of growth characteristics on selective medium, acidification of glucose and maltose, and gamma-glutamyltransferase activity (18). All the strains were serogroup A, type 4 and subtype P1.9, the same formula as strains belonging to subgroup III.

MLEE.

As the multilocus genotypes of these strains were identical to that of the reference strain LNP 6505 (Laboratoire des Neisseria, Institut Pasteur, Paris [LNP]), they were assigned to clone III-1 or subgroup III (Table 1) (17).

TABLE 1.

MLEE allele profile at 13 enzyme loci of 21 strains isolated from a 1998 Senegal outbreak and strain LNP 6505

| Strain(s) | Allele at indicated enzyme locusa

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | G6P | PEP | IDH | ACO | GD1 | GD2 | ADH | FUM | ALK | IP1 | IP2 | ADK | |

| LNP 6505 (A:4:P1.9, clone III-1) | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Outbreak strains | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

ME, malic enzyme; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; PEP, peptidase; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; ACO, aconitase; GD1, NADP-linked glutamate dehydrogenase; GD2, NAD-linked glutamate dehydrogenase; FUM, fumarase; ALK, alkaline phosphatase; IP1 and IP2, indophenol oxidases; ADK, adenylate kinase.

PFGE.

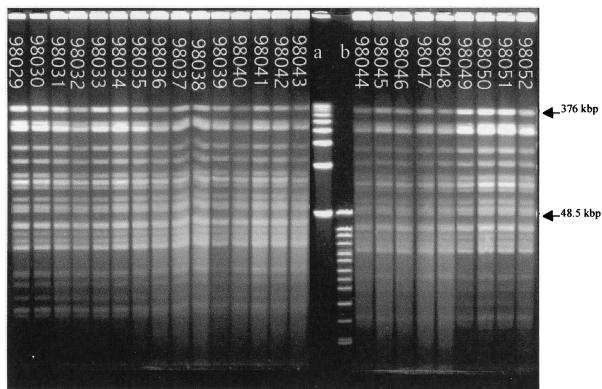

DNA macrorestriction fragments generated with BglII and analyzed by PFGE showed 24 indistinguishable fingerprint patterns (Fig. 1) similar to those of meningococcus strains isolated from African outbreaks since 1988 (13).

FIG. 1.

PFGE analysis of chromosomal DNA (ethidium bromide staining) of 24 strains isolated from a 1998 Senegal outbreak. DNA macrorestriction fragments were generated with BglII. All the patterns were identical. Lane a, PFGE marker I (Boehringer Mannheim); lane b, size standard (8 to 48 kb) (Bio-Rad).

MLST.

Since all PFGE fingerprint patterns were identical, we studied three randomly chosen strains by MLST. The comparison between sequences and existing alleles allowed us to assign to our sequences the allele numbers shown in Table 2. On the MLST website, the allele combination assigned these strains to ST5, as they were identical to the consensus at seven loci.

Antibiotic susceptibility.

All 24 strains were susceptible to penicillin, amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, and rifampin.

DISCUSSION

N. meningitidis A strains of subgroup III were responsible for an important outbreak in August 1987 in Mecca, Saudi Arabia (9, 22). As it was shown that 11% of American hajjis returning from the 1987 pilgrimage were carriers of group A meningococcus (10), we hypothesize that the proportion was the same among African pilgrims who brought this hypervirulent strain back to their countries. And as far back as 1988, outbreaks due to this clone began in Africa (Chad and Sudan). Year by year, this clone reached all the countries of the meningitis belt, and it was responsible for most epidemics in Africa by 1998 (3). In 1996, this clone was responsible for the biggest African outbreak ever known, with 150,000 cases reported (3, 24). Subgroup III is finishing its spread west of the meningitis belt of Africa, and this is the first time that this subgroup has been reported in connection with a meningitis outbreak in Senegal. As all the strains were identical by PFGE and MLEE, three randomly selected Senegalese strains were characterized by MLST and classified as ST5. According to the MLST website data, strains belonging to ST5 were also isolated in 1987 in Saudi Arabia and in Chad in 1988. ST5 was also detected in Gambia in 1997 and in Ghana in 1998. Preliminary investigations carried out in our laboratory on strains isolated in francophone African countries since 1988, and the few data available on the Internet, show that this ST was probably the most frequent in Africa between 1988 and 1998. Further investigations will be necessary to assess this idea.

As far as epidemiological data are concerned, epidemics occur periodically in the meningitis belt, and in Senegal, the last outbreak happened in 1986, with 825 cases reported; only a few cases have been reported since. Areas with annual rates exceeding 100 cases/100,000 persons in a given year are considered to have experienced an epidemic (12). In Senegal in 1998, annual rates were 267 cases/100,000 persons in the Fatick district, 122 cases/100,000 persons in Koungheul, and 97 cases/100,000 persons in Kaolack. A case fatality rate of 14.8% (2) seems more realistic than the 10% always reported by African countries, since in these countries, the first cases are usually not diagnosed and many cases in villages far from health facilities are unreported. This case fatality rate is comparable to the one observed in the Central African Republic in 1992 (15%) (8). In countries of the meningitis belt, outbreaks last 2 or 3 years. In 1999, a more severe outbreak reached the same regions in Senegal, with 3,138 cases and 418 deaths reported to the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland, on 14 March.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Part of this work was supported by funds from Ministère de la Défense (France) (DGA/PEA 98 08 14, contract 98 100 60).

We thank Jean-Michel Alonso, Unité des Neisseria, Institut Pasteur Paris, for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdillahi H. Monoclonal antibodies and Neisseria meningitidis. 1988. Typing and subtyping for epidemiological surveillance and vaccine development. Thesis. Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Méningite à méningocoque, le point sur cette endémie au Sénégal. Bulletin Epidemiologique du Ministère de la Santé Publique et de l'Action Sociale du Sénégal. 1998;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caugant D A. Population genetics and molecular epidemiology of Neisseria meningitidis. APMIS. 1998;106:505–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frasch C E, Zollinger W D, Poolman J T. Serotype antigens of Neisseria meningitidis and a proposed scheme for designation of serotypes. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7:504–510. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenwood B M. The epidemiology of acute bacterial meningitis in tropical Africa. In: William J D, Burnie J, editors. Bacterial meningitis. London, England: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 61–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lapeyssonie L. La méningite cérébrospinale en Afrique. Bull W H O. 1963;28(Suppl.):1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maiden M C J, Bygraves J A, Feil E, Morelli G, Russel J E, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant D A, Feavers I M, Achtman M, Spratt B. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merlin M, Martet G, Debonne J-M, Nicolas P, Bailly C, Yazipo D, Bougère J, Todesco A, Laroche R. Contrôle d'une épidémie de méningite à méningocoque en Afrique Centrale. Cahiers Santé. 1996;6:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health. Annual health report. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Ministry of Health; 1987. p. 279. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore P S, Harrison L H, Telzak E E, Ajello G W, Broome C V. Group A meningococcal carriage in travelers returning from Saudi Arabia. JAMA. 1988;260:2686–2689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore P S, Reeves M W, Schwarz B, Gellin B G, Broome C V. Intercontinental spread of an epidemic group A Neisseria meningitidis strain. Lancet. 1989;ii:260–263. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore P S, Plikaytis B D, Bolan G A, Oxtoby M J, Yada A, Zoubga A, Reingold A L, Broome C V. Detection of meningitis epidemics in Africa: a population-based analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:155–162. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicolas P, Parzy D, Martet G. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis of clonal relationships among Neisseria meningitidis strains from different outbreaks. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:541–544. doi: 10.1007/BF01708241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicolas P, Cavallo J-D, Fabre R, Martet G. Standardisation de l'antibiogramme de Neisseria meningitidis. Détection des souches relativement résistantes à la pénicilline. Bull W H O. 1998;76:393–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olyhoeck T, Crowe B A, Achtman M. Clonal population structure of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A isolates from epidemics and pandemics between 1915 and 1983. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:665–692. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poolman J T, Abdillahi H. Outer membrane protein serosubtyping of Neisseria meningitidis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988;7:291–293. doi: 10.1007/BF01963104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riou J-Y, Caugant D A, Selander R K, Poolman J T, Guibourdenche M, Collatz E. Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A strains from an outbreak in France by serotype, serosubtype, multilocus enzyme genotype and outer membrane protein pattern. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:405–409. doi: 10.1007/BF01968019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riou J-Y, Guibourdenche M. Neisseria and Branhamella: laboratory methods. Paris, France: Institut Pasteur; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salih M A M, Danielsson D, Bäckman A, Caugant D A, Achtman M, Olćen P. Characterization of epidemic and nonepidemic Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A strains from Sudan and Sweden. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1711–1719. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.8.1711-1719.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selander R K, Caugant D A, Ochman H, Musser J M, Gilmour M N, Whittman T S. Methods of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for bacterial population genetics and systematics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:873–884. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.5.873-884.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tikhomirov E. Meningococcal meningitis: global situation and control measures. World Health Stat Q. 1987;40:98–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahdan M H. Intercountry Meeting on Preparedness and Response to Meningococcal Meningitis Outbreaks. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1989. Epidemiology of meningococcal meningitis: an overview of the situation in the eastern Mediterranean region. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J-F, Caugant D A, Li X, Hu X, Poolman J T, Crowe B A, Achtman M. Clonal and antigenic analysis of serogroup A Neisseria meningitidis with particular reference to epidemiological features of epidemic meningitis in the People's Republic of China. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5267–5282. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5267-5282.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weekly Epidemiological Record. Cerebrospinal meningitis in Africa. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1996;42:318–319. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. WHO practical guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1995. Control of epidemic meningococcal disease. [Google Scholar]