Abstract

This protocol describes the culture of Leishmania parasites from skin biopsy samples of patients with cutaneous lesions. The use of antibiotics to prevent bacterial contamination of these cultures increases the ability of researchers to collect isolates for various research purposes including genetic analysis, in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Basic Protocol 1:

Culture of Leishmania from skin biopsy specimens

Introduction

The culture of Leishmania parasites from clinical samples can be used for both diagnostic and research purposes. As parasite loads between and within lesions can be variable, culture samples can provide larger amounts of parasite material for diagnostics. These clinical isolates can also provide valuable material for research, including genetic analyses as well as the in vitro and in vivo study of different strains of the parasite to further understanding of host-pathogen interactions and immune responses. Many cutaneous lesions are ulcerated, meaning a culture can rapidly be overtaken by skin bacteria, particularly in cases where lesions contain few parasites and may require longer periods of culture before parasites become established. This article describes the addition of a new combination of antibiotics and serial dilution to the culture protocol to help increase the likelihood of a contaminant-free culture being obtained. Previously utilized methods include culturing of biopsy homogenate or lesion aspirate in biphasic culture medium which does not include antibiotics in the growth media (Boggild et al., 2007; Boggild et al., 2010; Weigle et al., 1987). Culturing specimens to obtain parasites has been performed on both Old and New World strains of leishmania, as well as visceral strains where the sample is a bone marrow aspirate, liver or spleen biopsy or blood sample from an infected patient. Many clinical laboratories directly extract DNA from part of the patient sample in order to diagnose Leishmania infection as well as to type the strain in order to inform treatment options. This can be particularly vital for the Viannia strains as L. braziliensis can cause mucocutaneous disease, however PCR-based sequencing can have trouble differentiating between these closely related parasite strains, particularly when low amounts of parasite DNA are present in the sample. The ability to reliably provide outgrows in this setting helps to provide an accurate diagnosis. Clinical isolates also provide sufficient material to perform sophisticated genetic analyses that allow researchers to examine parasite evolution, parentage, hybridization and genes linked to drug resistance. Expanding the collection of isolated strains will provide a valuable resource for Leishmania research (Domagalska et al., 2019; Espada et al., 2021; Franssen et al., 2020; Van den Broeck et al., 2020).

Biosafety Considerations

CAUTION: Leishmania are a potential biohazard. The appropriate Institution Biosafety Review Board should be consulted before beginning these protocols. In our institution, research with Leishmania is conducted under Biosafety Level 2 (BSL2). This includes lab coats, nitrile gloves and steps to minimize the risk of injury involving sharps. Material should be placed in a biohazard bag and autoclaved or incinerated. Liquids should be decontaminated with 10% bleach. Surfaces and equipment should be decontaminated with 70% ethanol

Human-derived materials

CAUTION: Human tissue must be obtained with the approval of the appropriate Institutional Review Board. All human tissue should be treated as potentially infectious. Follow all appropriate guidelines and regulations for the use and handling of human-derived materials.

Basic Protocol 1: CULTURE OF LEISHMANIA FROM PATIENT SKIN BIOPSY SAMPLES

This method provides an alternative to tube- or plate-based culture assay using NNN media and blood agar slopes (Boggild et al., 2010; Sacks & Melby, 2015) through the use of a plated culture system and a new combination of antibiotics to prevent the growth of bacteria present on the skin and lesion. For murine experiments the use of gentamicin has generally been sufficient, however, patient samples often contain bacteria that are not susceptible to gentamicin, necessitating the use of a new combination of broad spectrum antibiotics that will stop bacterial growth. The use of serial dilution during the plating stage increases the likelihood of obtaining a successful, uncontaminated culture.

Materials

Full thickness punch biopsy sample

Complete M199 medium (see Reagents and Solutions)

Piperacillin stock 50mg/mL (Sigma P8396)

Cefotaxime stock 100mg/mL (Sigma C7039)

Phosphate buffered saline (Life Technologies 10010023 or equivalent)

Laminar flow hood (Nuaire Class II Type A2 or equivalent)

Sterile 35mm petri dish (Corning 351008 or equivalent)

15 mL screw cap tube (Greiner Bio-One 188261 or equivalent)

70 micron cell strainer (Corning 352350 or equivalent)

3mL syringe (sterile)

Sterile forceps

Serological pipettes (sterile)

96 well flat bottom tissue culture plate (Corning 353072 or equivalent)

20–200 μL pipette

Parafilm or tape

26°C Incubator without CO2 (Thermo Scientific or equivalent)

Inverted light microscope with 4x and 20x objectives (Olympus or equivalent)

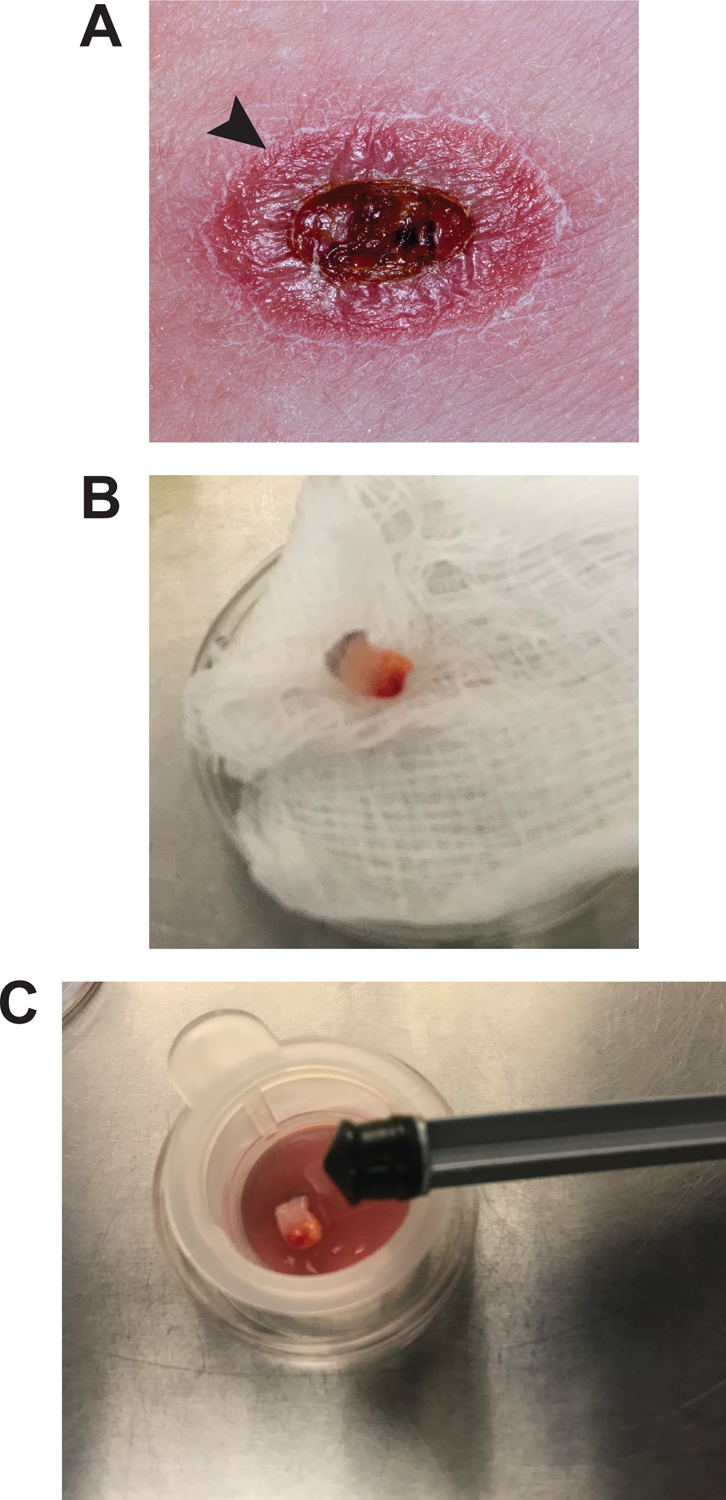

- The full thickness 4mm skin punch biopsy specimen is typically collected by trained clinic personnel from the raised edge of the lesion (Fig. 1A) and is provided in a screw top (or other) container on gauze moistened with sterile saline or in sterile media. Multiple samples can be processed in one session but should be handled sequentially up to step 6 in order to avoid contamination, mixing or mislabeling of samples.If biopsy tissue is being processed immediately, allow the tissue piece to sit on sterile gauze for several minutes to allow blood to drain. At this stage the tissue sample can be divided if using some for DNA/RNA extraction, histology or frozen storage. It is not recommended to divide the sample into more than three pieces, this should be done extraction can be stored in the extraction buffer for the protocol being used (for example through the full thickness of the sample so that all layers of the skin are included in each sample. The full thickness biopsy sample is shown in Figure 1B. Samples for DNA/RNA Trizol, Qiagen extraction buffers or 100% ethanol) at −80°C. Samples for histology can be fixed in 10% formalin before embedding and sectioning per the general protocol found in (Canene-Adams, 2013).If not processing immediately, samples can be left at room temperature or refrigerated for up to 4 hours. In these circumstances the biopsy sample(s) should be lightly sprayed with 70% ethanol and thoroughly blotted dry to remove surface bacteria and fungi. Do not soak the sample in ethanol. Longer term storage recommendations from the CDC indicate storage in sufficient sterile media to cover the sample for a period of 24–48 hours or refrigerated if overgrowth with bacterial or fungal contaminants is likely. Please refer to the CDC Leishmania diagnosis guide in the reference list for details.

- For homogenization, in the laminar flow hood using aseptic technique, prepare the deeper half of a 35mm petri dish by placing the 70 micron cell strainer unit inside the dish and adding 1–2 mL of sterile PBS as shown in Fig. 1C.Larger volumes of PBS will make it more difficult to maneuver the tissue during homogenization so smaller volumes are recommended.

- Place the surface sterilized tissue sample inside the cell strainer unit with sterile forceps and use the rubber end of a 3 mL syringe plunger as a pestle to homogenize the tissue through the filter (Fig. 1C).To surface sterilize biopsy samples, lightly spray with 70% ethanol and thoroughly blotted dry immediately.Not all of the tissue will become suspended as the adipose layer is more difficult to dissociate mechanically. As the parasite is present mostly in the epidermis and dermis, this will not impact the suspension of infected cells.If cell strainers are not available to you, the tissue can also be homogenized between two sterile pieces of fine mesh or minced finely with a sterile scalpel blade.

Wash filter with additional 3 mL of sterile PBS.

Transfer PBS containing the cell suspension to a 15 mL screw cap conical tube using a sterile serological pipette.

- Centrifuge at 1500x g for 10–15 minutes.This centrifugation step can be performed at room temperature or 4°C. Centrifuging at 4000 rpm will pellet the cells as well as any parasite that may have been released by cells ruptured during homogenization.

- Prepare C-M199 for use by adding piperacillin and cefotaxime. The listed stocks of these antibiotics are 1000x concentration so add 1 μL per mL of media to be used. Estimate 1 mL per sample.If a large number of samples are being processed in a short time frame (1 week) then a large bottle of media containing antibiotics can be made, otherwise make as needed.C-M199 media is not critical to this protocol and other media that support the growth of Leishmania parasites (Schneider’s, RPMI 1640) can also be used (Boggild et al., 2010).

Aspirate liquid from the tissue pellet.

Resuspend cells in 0.2 mL C-M199 media containing the antibiotic cocktail at working concentrations.

- Prepare a 96 well plate by adding 0.1 mL of C-M199 containing added antibiotics (from Step 7) to the first well and then 0.15 mL to at least 3 subsequent wells for serial dilution. This can be done in duplicate if desired. If handling more than one sample steps 10–12 can be completed with a multichannel pipette or samples can be pipetted individually with care taken to avoid transfer to incorrect wells on the plate.Make sure to label sample identification, processing date and dilutions on plate lid.

Add 0.1 mL of cell suspension to the first well and mix by pipetting up and down gently to make 1:1 (2-fold) dilution.

- With a new pipette tip, transfer 0.05 mL of the first well into the next well. Repeat until all dilutions have been mixed, using a new pipette tip for each dilution. These will be 4-fold dilutions for each step (so 1:8, 1:32 etc).Serial dilution serves two purposes in this protocol; firstly, it dilutes the tissue component of the sample allowing for easier visualization of any parasite that may grow out. Secondly, it helps to dilute any potential contaminating bacteria that may be resistant to the antibiotics used and increases the chances of an uncontaminated isolate. Fungal contamination can also occur and samples from patients with obvious fungal infection should not be cultured. Further discussion can be found in Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting.

When all samples have been plated out, close the lid of the plate and seal well with either parafilm or tape to cover the seam in order to prevent evaporation.

Incubate the plate at 26°C.

- Wells can be screened by light microscopy starting the next day. Examples of negative and positive wells by light microscopy using a 20x lens are shown in Figure 2A and 2B respectively).Samples with high parasite loads can begin outgrowth rapidly (2–3 days). Samples containing fewer parasites may take several days (7–10 days) to have noticeable parasites in the wells. If no parasites are observed at this stage and you wish to continue the culture then the addition of an extra 0.1 mL of media containing antibiotics per well can be performed and the plate resealed and incubated for a longer period of time. Please note that this method will generally not yield parasite cultures when samples are from patients already undergoing drug treatment for Leishmaniasis.

- Positive wells can be harvested by transferring the well contents using a sterile pipette to a 12.5cm2 tissue culture flask containing 3–5 mL C-M199 or other growth media or 6 well plate containing 2–3 mL media for further growth. The addition of piperacillin and cefotaxime are no longer required at this stage if there is no visible bacterial contamination. Further diagnostic or experimental usage can then be undertaken, or stabilates can be cryopreserved for future work as described in Support Protocol 4 of (Sacks & Melby, 2015).If the outgrow sample will be used for further culture and preparation of stabilates then only samples with no bacterial or fungal contamination should be selected. If the outgrow is for confirming molecular diagnostics or other molecular analysis then this is less critical. For qPCR diagnostics the extraction of DNA from 0.05 mL of the actively growing well contents will yield sufficient DNA. Scaling to a larger volume will yield sufficient material for any molecular application including whole genome sequencing.Passage history should be recorded for all samples, this will be particularly helpful for genetic studies.

Figure 1.

Sterile mechanical homogenization of bunch biopsy specimen.

A. The biopsy specimen is obtained from the raised margin of the lesion (arrow).

B. The full thickness punch biopsy specimen after collection and prior to homogenization.

C. In a laminar flow hood the sterile 35mm culture dish contains a sterile filter, 1–2mL of sterile PBS and the specimen. The rubber end of a sterile 3mL syringe plunger will be used to homogenize the specimen through the filter.

Figure 2.

Examples of cultures obtained from skin biopsy specimens.

A. Negative culture. No promastigote forms of leishmania are observed in the culture.

B. Positive culture. Large clumps of parasites can be seen attached to a cluster of cells as well as numerous free-swimming promastigotes in culture (examples marked with arrows). All samples are light microscopy images taken at 20x magnification.

Reagents and solutions

C-M119 media (500mL)

100 mL heat inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Gemini Bioscience or similar).

If FBS is not available already heat inactivated then this can be performed by incubating serum at 56°C for 60 minutes.

5 mL 10mM adenine (Sigma A8751) in 50mM HEPES acid

1 mL 0.25% (w/v) hemin (Sigma 51280) in 50% (v/v) triethanolamine (Sigma 90278)

5 mL 100x penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies 15140–122)

5 mL 100x L-glutamine (Life Technologies 35030–061)

2 mL 0.05% biopterin (Sigma B2517) in 0.01 N NaOH

0.5 mL biotin (Sigma B4639) in 95% ethanol

13.2mL 10x M199 with Earle’s salts (Life Technologies 11825–015)

368.3 mL 1x M199 with Hank’s salts and 25mM HEPES acid (Life Technologies 12350–039)

Media should be filter sterilized and can be stored for up to 4 weeks at 4°C

Commentary

Background information

There are many methods in use for the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis, including impression smears, histology and various molecular techniques with a range of degrees of sensitivity (Aronson et al., 2016; Berman, 1997; Boggild et al., 2010; Reed, 1996; Saab, El Hage, Charafeddine, Habib, & Khalifeh, 2015; Weigle et al., 1987). Contamination of culture specimens with bacteria and fungi has historically been an issue, with cultures becoming overrun before promastigotes have a chance to become established, resulting in the loss of these samples. While exact data are not frequently provided, with samples often simply reported as negative for the culture method, one study reports a 15% rate of contamination for their outgrow cultures (Weigle et al., 1987). Given that cutaneous lesions are frequently ulcerated, the presence of bacteria and fungi is to be expected and some culture media, such as the C-M199 used in this protocol, contain penicillin and streptomycin to prevent bacterial growth. However, this can often be insufficient to control the variety of bacteria present on the skin and in the lesion. The antibiotics piperacillin and cefotaxime were selected as both are broad spectrum (targeting gram-positive and both gram-positive and-negative bacteria respectively), inexpensive and do not affect Leishmania, allowing for the culture growth of a larger proportion of samples from both Old and New World strains. While molecular diagnostic techniques negate this issue (Aronson et al., 2016; Stevenson, Fedorko, & Zelazny, 2010; Weirather et al., 2011; Zelazny, Fedorko, Li, Neva, & Fischer, 2005), genome-level genetic studies of clinical isolates require larger amounts of DNA than is often available from the extraction of a punch biopsy or skin scrape specimen and thus typically necessitate a culture outgrow, although recent advances such as capture enrichment sequencing have largely overcome this requirement (Domagalska et al., 2019). While this advance in sequencing technology helps to address issues such as culture acquired genetic artifacts and even the inability to obtain a culture isolate, there are still caveats and it is currently still not possible to reliably capture 100% of the parasite genome. This is due to a proportion of the probes in this method having sequence homology to human DNA and thus needing to be removed from the probe pool. Additionally, if parasite DNA is present in low abundance then there is a reduced chance of acquiring a whole genome using this method. Successfully obtaining a culture isolate and sequencing is currently still the most reliable way to obtain the whole genome of Leishmania isolates acquired from patients with currently available technology.

Culture isolation can also be advantageous in the instance of molecular diagnostic techniques where the sample contains too little parasite material to allow for reliable typing, providing for a confirmation of diagnosis and helping to inform treatment choices. This can be particularly relevant for patients infected with L. braziliensis, which can cause disfiguring, debilitating and potentially fatal mucocutaneous disease if left untreated. Direct inoculation of susceptible animals such as mice or hamsters are an additional method by which clinical isolates can be obtained (Boggild et al., 2010; Weigle et al., 1987). However, such work, as well as work utilizing clinical outgrow specimens, requires access to research animals and the approval of your Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee or the equivalent regulatory body. The use of animal models of all forms of leishmaniasis as well as other associated methods such as parasite purification and cryopreservation are discussed in detail in Current Protocols in Immunology (Sacks & Melby, 2015). For overviews of the spectrum of disease caused by Leishmania spp., treatment options and updated global epidemiology data please visit the World Health Organization or the Center for Disease Control and Prevention websites that are listed in the Literature Cited Section.

Critical Parameters

The most critical factor influencing the success this protocol is the ability to control the introduction and growth of contaminants in the sample. When the punch biopsy is initially collected by trained personnel, the site of collection is disinfected (please see the CDC Diagnosis Guide in the Internet Resources section for details) and the biopsy sample is then kept in sterile sealed container, with or without media. These samples can be kept refrigerated if not being processed rapidly to prevent bacterial or fungal overgrowth. A gentle surface sterilization prior to processing in a laminar flow hood helps to remove any remaining or subsequently acquired contaminants on the sample surface and the use of sterile equipment and aseptic technique prevents the introduction of contamination from the surroundings. Changing the tips between serial dilution wells also minimizes the risk of contaminant transfer.

While the presence of bacteria in the clinical sample is the focus of this protocol, fungal contamination is another potential factor impacting success in obtaining isolates. As leishmania and fungal ergosterol are very similar (Roberts et al., 2003), many antifungals can kill or inhibit the growth of leishmania and thus should not be used in the culture media for this protocol. While fungal contamination has not been observed in the samples received for these studies, we have found a 1:2500 dilution of proprionic acid (Sigma, 402907) to be helpful in reducing, fungal contamination of sandfly midgut cultures without any deleterious effects on the parasite so this may be of use in sample sets where fungal contamination is considered a high risk (Paun and Sacks, unpublished data) and should be included in the media in Step 7 of the main protocol.

The final factor affecting success is the placement collection site of the punch biopsy sample. This is a variable that to a large extent is out of the control of the researcher as parasite distribution within the lesion is not uniform, leading to variations in the number of amastigotes potentially present in biopsy specimens taken from two different locations on the raised edge of the lesion. It should be noted that culture methods are compatible with other assay types such as lesion smears, histology and PCR testing and can be performed in conjunction with these for comparative studies (Boggild et al., 2007; Boggild et al., 2010; Weigle et al., 1987). It should also be noted that while this protocol refers specifically to skin punch biopsy samples and has not been empirically tested for other dermal samples, it could easily be applied to skin scraping and skin brush samples from the wash in Step 4 onwards. These samples have been demonstrated to be high in parasite DNA and collection of these may be more amenable to patients and researchers, particularly in field settings (Suarez et al., 2015). Careful, aseptic handing of the specimen in conjunction with Basic Protocol 1 will optimize the possibility of obtaining a successful culture outgrow from the specimen.

Troubleshooting

See table 1 for troubleshooting considerations and suggestions.

Table 1:

Troubleshooting guide.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No parasite growth | Differential diagnosis | Additional diagnostics from medical providers may have determined a differential diagnosis such as bacterial infection or skin cancer. If a portion of the biopsy specimen was saved, DNA can be extracted and tested by PCR or qPCR to confirm absence of leishmania. If negative for Leishmania the sample can be excluded from the study if appropriate and the culture discarded. |

| Patient undergoing treatment | No live leishmania is likely to be recoverable from this patient sample and samples should only be considered for molecular analyses if early in the course of treatment. | |

| Media evaporation | Plate not sealed correctly | If evaporation has occurred then 0.1mL antibiotic containing media to each well and reseal the plate thoroughly. If you notice loss of integrity of the seal during your daily visual screen of the plate, replace the seal of the plate. If sample wells have dried out then the plate should be discarded as no live cultures will be obtained. |

| Bacterial contamination | Poor aseptic technique Bacteria not susceptible to antibiotics used |

In both instances the addition of 50μg/mL gentamicin (Sigma G1397 50mg/mL stock) may be tried to kill bacteria, however it is most likely that the culture samples will need to be discarded and noted as such for study purposes. |

| Fungal contamination | Poor aseptic technique Specimen contained fungal spores |

The addition of a 1:2500 dilution of proprionic acid (Sigma 402907) may be helpful in samples with a low level of contamination. Alternatively, if the risk of fungal contamination is considered high this can be added in the initial media made up in Step 7 of Basic Protocol 1 and portion of the sample kept for molecular analysis if applicable. If samples are heavily contaminated then they will need to be discarded and noted as such for study purposes. |

Understanding Results

Both of the examples given utilize patient punch biopsies provided by the Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases (LPD) clinical staff at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as well as initial qPCR diagnostic results from the Department of Laboratory Medicine at the NIH. Samples were processed using their standard approved protocols. Leishmania diagnostics and species identification using 7SL as the target gene (Stevenson et al., 2010; Zelazny et al., 2005) were performed on DNA extracted from one of two punch biopsy samples, the other was used to obtain culture isolates as described in Basic Protocol 1.

Patient #1:

Skin biopsy DNA tested positive for Leishmania with (Ct=28), however sequencing could not definitively differentiate between Viannia strains. The second biopsy was cultured, and positive wells were observed in 4 days. DNA was extracted from the culture isolate and typed by multi locus sequencing together with the original DNA sample to confirm a diagnosis of L. braziliensis.

Patient #2:

Skin biopsy DNA tested positive for Leishmania (Ct=41), the PCR product was not able to be sequenced due to low concentration. The second biopsy was cultured, and positive wells were observed in 3 days. DNA was extracted from the culture isolate and the standard 7SL qPCR and sequencing was able to diagnose L. panamensis.

For both patients the culture sample was able to provide a confirmed diagnosis that informed their treatment. The culture isolates were expanded and cryopreserved for future research. In these examples two different punch biopsies were used, perhaps accounting for the discrepancy between qPCR Ct values and the incubation time in which parasites were observed in culture. When both assays are performed on a single, divided biopsy specimen there is likely to be good correlation between these two variables.

Time considerations

Once a sample is obtained, the initial processing time for Steps 1–14 of Basic Protocol 1 is approximately 30 minutes for a single sample. 10–15 minutes should be added for each additional sample as the centrifugation step can be performed on multiple samples at a time.

The time to obtaining a culture outgrow is variable and can take 1–14 days in a positive sample, depending on the parasite load of the initial biopsy sample. Cultures should be checked daily for the presence of parasites and to ensure that there is no evaporation of media. Approximately 10–30 minutes would be needed to screen a plate by microscopy, depending on the number of wells. 30 minutes should be allocated for making and adding fresh media to wells and resealing the plate in the case that evaporation is observed or for continuation of the culture for additional time.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Samples and photographs of lesions were obtained from patients who provided written consent to be included in Clinical Protocol 01-I-0238. I would like to thank Dr. Theodore Nash (retired) and Dr. Elise O’Connell of the Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases (LPD), NIAID for their helpful discussions regarding antibiotic selection and provision of samples. I would also like to thank the LPD clinical staff for their collection of patient samples, the NIH Clinical Center Department of Laboratory Medicine for the provision of biopsy DNA samples and the patients who agree to participate in the clinical protocol. I thank Drs. Michael Grigg and David Sacks for critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement.

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

Data sharing

The data, tools and material (or their source) that support the protocol are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Internet Resources

World Health Organization

https://www.who.int/health-topics/leishmaniasis#tab=tab_1

Center for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/index.html

Literature cited

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, Pearson R, Lopez-Velez R, Weina P, . . . Magill A (2016). Diagnosis and Treatment of Leishmaniasis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis, 63(12), e202–e264. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JD (1997). Human leishmaniasis: clinical, diagnostic, and chemotherapeutic developments in the last 10 years. Clin Infect Dis, 24(4), 684–703. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggild AK, Miranda-Verastegui C, Espinosa D, Arevalo J, Adaui V, Tulliano G, . . . Low DE (2007). Evaluation of a microculture method for isolation of Leishmania parasites from cutaneous lesions of patients in Peru. J Clin Microbiol, 45(11), 3680–3684. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01286-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggild AK, Ramos AP, Espinosa D, Valencia BM, Veland N, Miranda-Verastegui C, . . . Llanos-Cuentas A (2010). Clinical and demographic stratification of test performance: a pooled analysis of five laboratory diagnostic methods for American cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 83(2), 345–350. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canene-Adams K (2013). Preparation of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue for immunohistochemistry. Methods Enzymol, 533, 225–233. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420067-8.00015-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domagalska MA, Imamura H, Sanders M, Van den Broeck F, Bhattarai NR, Vanaerschot M, . . . Dujardin JC (2019). Genomes of Leishmania parasites directly sequenced from patients with visceral leishmaniasis in the Indian subcontinent. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 13(12), e0007900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espada CR, Albuquerque-Wendt A, Hornillos V, Gluenz E, Coelho AC, & Uliana SRB (2021). Ros3 (Lem3p/CDC50) Gene Dosage Is Implicated in Miltefosine Susceptibility in Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis Clinical Isolates and in Leishmania (Leishmania) major. ACS Infect Dis, 7(4), 849–858. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franssen SU, Durrant C, Stark O, Moser B, Downing T, Imamura H, . . . Cotton JA (2020). Global genome diversity of the Leishmania donovani complex. Elife, 9. doi: 10.7554/eLife.51243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SG (1996). Diagnosis of leishmaniasis. Clin Dermatol, 14(5), 471–478. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(96)00038-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CW, McLeod R, Rice DW, Ginger M, Chance ML, & Goad LJ (2003). Fatty acid and sterol metabolism: potential antimicrobial targets in apicomplexan and trypanosomatid parasitic protozoa. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 126(2), 129–142. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00280-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab M, El Hage H, Charafeddine K, Habib RH, & Khalifeh I (2015). Diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis: why punch when you can scrape? Am J Trop Med Hyg, 92(3), 518–522. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks DL, & Melby PC (2015). Animal models for the analysis of immune responses to leishmaniasis. Curr Protoc Immunol, 108, 19 12 11–19 12 24. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1902s108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson LG, Fedorko DP, & Zelazny AM (2010). An enhanced method for the identification of Leishmania spp. using real-time polymerase chain reaction and sequence analysis of the 7SL RNA gene region. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 66(4), 432–435. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez M, Valencia BM, Jara M, Alba M, Boggild AK, Dujardin JC, . . . Adaui V (2015). Quantification of Leishmania (Viannia) Kinetoplast DNA in Ulcers of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Reveals Inter-site and Inter-sampling Variability in Parasite Load. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 9(7), e0003936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broeck F, Savill NJ, Imamura H, Sanders M, Maes I, Cooper S, . . . Dujardin JC (2020). Ecological divergence and hybridization of Neotropical Leishmania parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 117(40), 25159–25168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1920136117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigle KA, de Davalos M, Heredia P, Molineros R, Saravia NG, & D’Alessandro A (1987). Diagnosis of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia: a comparison of seven methods. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 36(3), 489–496. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirather JL, Jeronimo SM, Gautam S, Sundar S, Kang M, Kurtz MA, . . . Wilson ME (2011). Serial quantitative PCR assay for detection, species discrimination, and quantification of Leishmania spp. in human samples. J Clin Microbiol, 49(11), 3892–3904. doi: 10.1128/JCM.r00764-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazny AM, Fedorko DP, Li L, Neva FA, & Fischer SH (2005). Evaluation of 7SL RNA gene sequences for the identification of Leishmania spp. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 72(4), 415–420. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15827278 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]