Abstract

The nucleotide sequences of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of rRNA genes of 24 isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum were examined. The results indicate that the sequences of ITS regions in different isolates are not identical. Sequence variations were found at 20 positions in the 496 bp that were sequenced. Ten different sequence patterns, designated types A through H, were observed when the sequences from the 24 isolates were aligned. Twelve isolates from Indianapolis were classified into four different types. Two isolates from New York belonged to type G. Three isolates from different cities were type F. The remaining six isolates were of different types.

Histoplasma capsulatum causes histoplasmosis, a mycosis with an array of manifestations (19, 26). Some individuals may have no symptoms of infection. Some patients may experience mild flu-like symptoms or pneumonia, while others, especially those who are immunosuppressed, may develop lesions in the skin, brain, intestine, adrenal glands, and bone marrow (1, 2, 3, 7, 9, 13, 18, 22, 26). H. capsulatum is prevalent in humid river basins, such as the Mississippi Valley and the Ohio River Valley regions in the United States. H. capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus. It grows as mold and produces aerial hyphae at 25 to 30°C but forms yeast colonies when grown in the laboratory on blood agar at 37°C. The mycelial form of the organism is usually found in soil with high nitrogen and phosphate content. When conidia or hyphal fragments of the organism are inhaled by humans or animals, the organism converts to the yeast form.

Multiple strains of H. capsulatum have been found. Distinctions of various strains may be based on colony morphology (4) or polymorphism of the genome (6, 11, 21, 23). Three classes of H. capsulatum isolates were discovered by Vincent et al. (23) based on restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). The temperature-sensitive Downs strain was designated class 1, most isolates from North America were designated class 2, and most isolates from Central and South America were grouped as class 3. An isolate from a soil sample from Florida was found to have a different mtDNA RFLP type, and this was designated class 4 (21). With combinations of mtDNA and ribosomal DNA (rDNA) RFLP patterns, at least five additional types were identified within the eight mtDNA class 2 isolates (21).

An RFLP was also found in a nuclear gene, yps-3 (11). Six yps-3 RFLP types, designated classes 1 to 6, have been discovered. The first four classes were equivalent to the mtDNA classes 1 to 4. Classes 5 and 6 were new types; however, five novel mtDNA RFLP types were found among the nine class 5 isolates (11). In a different study, each of 29 class 2 isolates was found to have different RAPD (random amplification of polymorphic DNA) patterns when evaluated with at least three random primers (12). Another typing method was reported by Carter et al. (6). They examined 30 isolates from Indianapolis and 8 from Colombia with 11 biallelic and 3 multiallelic markers. These markers were amplified from the H. capsulatum genome by PCR with specific sets of primers, and the amplified products were analyzed for the presence or absence of certain restriction sites. Each of the 30 isolates from Indianapolis was shown to be different as to these markers, whereas the 8 isolates from Colombia were found to have patterns identical to the 11 biallelic markers but different patterns with the three multiallelic markers. Kasuga et al. examined nucleotide sequence variations in four different genes encoding ADP-ribosylation factor, H antigen precursor, delta-9 fatty acid desaturase, and alpha-tubulin, and classified H. capsulatum isolates into six different clades (10).

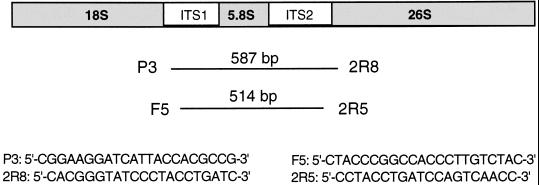

In this study, we have examined the nucleotide sequences of a region which includes ITS1, the 5.8S rRNA gene, and ITS2 of 24 H. capsulatum isolates. ITS1 is the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region 1 located between the 18S and the 5.8S rRNA genes, and ITS2 is located between the 5.8S rRNA gene and 26S rRNA gene (Fig. 1). Sequence variations were found in both ITS regions. This sequence variation allowed us to classify the 24 isolates into 10 different types.

FIG. 1.

Nested PCR for H. capsulatum ITS regions. The first PCR is performed with primers P3 and 2R8, and the second PCR is done with primers F5 and 2R5. The regions amplified and the sizes of PCR products are as indicated. Primer sequences are shown in the lower portion of the diagram.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

Twenty-four H. capsulatum isolates, designated isolates 1 to 24, were used for this study (Table 1). One isolate (number 6) is a lab strain originally obtained from a patient in Indianapolis. Isolates 11 and 19 were obtained from the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, Indiana University Hospital. The remaining 21 isolates, including the class 1 Downs strain (8, 20), were acquired from the Histoplasmosis Reference Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine.

TABLE 1.

Specimens used in this study

| Specimen no. | Location | Yr | Underlying disease | Type (GenBank accession no.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1992 | AIDS | A-1 (AF129538) |

| 2 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1992 | AIDS | A-1 (AF129538) |

| 3 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1992 | AIDS | A-1 (AF129538) |

| 4 | St. Louis, Mo. | 1992 | AIDS | A-1 (AF129538) |

| 5 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1992 | AIDS | A-1 (AF129538) |

| 6 | Indianapolis, Ind. | Unka | Unk | A-1 (AF129538) |

| 7 | Birmingham, Ala. | 1992 | AIDS | A-2 (AF129539) |

| 8 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1990 | AIDS | A-2 (AF129539) |

| 9 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1989 | AIDS | A-2 (AF129539) |

| 10 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1988 | AIDS | A-2 (AF129539) |

| 11 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1997 | AIDS | A-2 (AF129539) |

| 12 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1989 | AIDS | A-3 (AF129540) |

| 13 | New York, N.Y. | 1990 | AIDS | A-3 (AF129540) |

| 14 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1989 | Non-AIDS | A-3 (AF129540) |

| 15 | Houston, Tex. | 1992 | AIDS | B (AF129541) |

| 16 | Ft. Wayne, Ind. | 1979 | Cancer | C (AF129542) |

| 17 | Los Angeles, Calif. | 1991 | AIDS | D (AF129543) |

| 18 | Houston, Tex. | 1992 | AIDS | E (AF129544) |

| 19 | Indianapolis, Ind. | 1996 | Non-AIDS | F (AF129545) |

| 20 | Houston, Tex. | 1992 | AIDS | F (AF129545) |

| 21b | Southern Illinois | 1969 | None | F (AF129545) |

| 22 | New York, N.Y. | 1991 | AIDS | G (AF129546) |

| 23 | New York, N.Y. | 1992 | AIDS | G (AF129546) |

| 24 | Los Angeles, Calif. | 1990 | AIDS | H (AF129547) |

Unk, unknown.

Class 1 Downs strain.

DNA isolation.

DNA isolated from H. capsulatum isolates was used as the template for the PCR. The yeast form of the organism was used. The organisms obtained from culture were pelleted by centrifugation in an Eppendorf centrifuge for 5 min and then resuspended in 500 μl of proteinase K buffer (50 mM KCl, 15 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], and 0.5% NP-40) containing 500 μg of proteinase K per ml. After incubation at 37°C overnight, the mixture was extracted with phenol and chloroform. The DNA in the aqueous phase was precipitated with ethanol, the ethanol was removed by vacuum drying, and the DNA was dissolved in 50 μl of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA).

Design of PCR primers.

Two pairs of PCR primers were first designed to develop a nested PCR to amplify the ITS regions of H. capsulatum. These primers were based on the ITS sequence of Ajellomyces capsulatus, the ascomycetous teleomorph form of H. capsulatum, deposited in the GenBank (accession number U18363). The sequence 5′-CGGAAGGATCATTACCACGCCG-3′, located at nucleotide positions 39 to 60, was chosen as the 5′ primer (designated P3), and the other sequence, 5′-CAGCGGGTATCCCTACCTGATC-3′, complementary to nucleotides 604 to 625, was selected as the 3′ primer (designated 2R8) of the first PCR. This PCR is expected to amplify a fragment of 587 bp (Fig. 1). The sequences 5′-CTACCCGGCCACCCTTGTCTAC-3′, located at nucleotide positions 101 to 122, and 5′-CCTACCTGATCCAGTCAACC-3′, complementary to nucleotides 597 to 614, were used for second PCR primers and designated F5 and 2R5, respectively. The expected size of the second PCR product is 514 bp (Fig. 1).

PCR conditions.

Nested PCR was performed to amplify the entire ITS regions of H. capsulatum. The reaction mixture contained 100 ng of template DNA, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3; 50 mM KCl; 3 mM MgCl2; 0.001% gelatin), 60 pmol each of PCR primers P3 and 2R8, 0.2 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase in a total volume of 100 μl. The PCR mixture was overlaid with 100 μl of mineral oil to prevent evaporation during thermal cycling. The PCR was performed in three stages. The initial stage was a 10-min denaturation at 94°C. The second stage was 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 47°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min. The final stage was a 10-min extension at 72°C.

Then, 5 μl of the first PCR product was used for the second PCR, which was performed with primers F5 and 2R5. The PCR conditions were the same as those of the first PCR, except that the MgCl2 concentration was reduced to 2 mM and the primer annealing temperature was raised to 55°C. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 6% polyacrylamide gel to determine their sizes.

Cloning and sequencing of PCR products.

PCR products were cloned into the TA cloning vector pCRII as described previously (14). Nucleotide sequencing was performed by using the Sequenase kit (version 2; Amersham Corp., Cleveland, Ohio). Primers (M13-40, 5′-GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′; reverse, 5′-AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGA-3′) that anneal to regions on the vector flanking the inserts were used for sequencing.

RESULTS

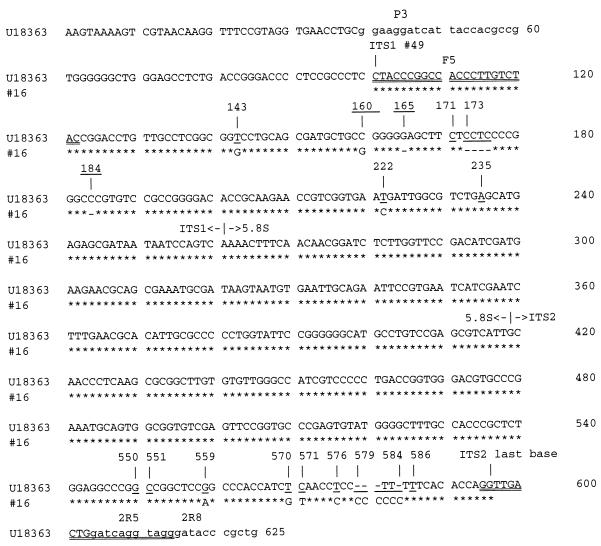

A fragment of approximately 510 bp was produced when the nested PCR was performed on a DNA sample from specimen 16. Since this was the expected size, the PCR product was cloned and sequenced. The sequence thus obtained was compared with the U18363 sequence (Fig. 2). The new sequence (sequence 16) was found to differ from U18363 at several positions. Position 143 is a G instead of a T, and position 160 is a G instead of a C. Bases are missing at positions 165, 173 to 176, and 184. The following changes are also present: T to C at position 222, G to A at position 559, T to G at position 570, C to G at position 571, and T to C at position 576. An insertion of three C residues is found between positions 579 and 581, and an extra C is present at position 584.

FIG. 2.

Sequences of ITS1, 5.8S rRNA gene, and ITS2 of H. capsulatum. U18363 is the A. capsulatus sequence deposited in the GenBank database. Sequence #16 (positions 101 to 596) is the first H. capsulatum sequence obtained in this study. Sequences written in lowercase letters are the first PCR primers (P3 and 2R8). Double-underlined sequences are the second PCR primers. Bases that are underlined are the ones found to be variable among the 24 isolates; the position numbers of most of these bases are indicated. Underlined position numbers denote bases that are not variable among the 24 isolates but are different between the two sequences compared. Bases in sequence #16 that are the same as for U18363 are represented with asterisks. Missing bases in either sequences are marked by hyphens.

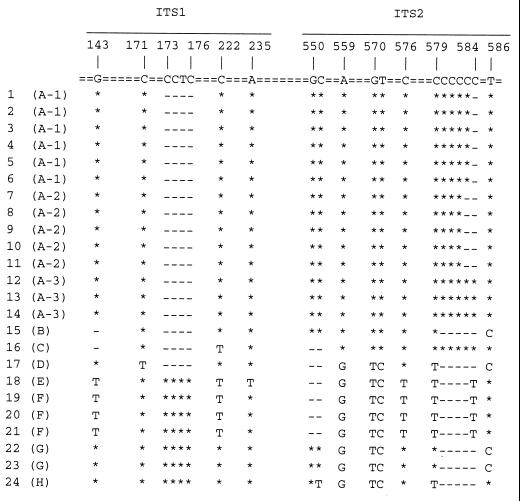

This result suggests that sequence variations exist in the ITS regions of H. capsulatum. To determine whether this sequence variation can be used for typing, the sequences of the ITS regions and the 5.8S rRNA gene of 23 additional isolates were determined. Among the 496 bp that were completely sequenced, 20 positions were found to be variable, including 8 (positions 143, 171, 173 to 176, 222, and 235) in the ITS1 and 12 (positions 550, 551, 559, 570, 571, 576, and 579 to 584) in the ITS2 region. These positions in various isolates have bases missing or nucleotides different from each other. Based on these sequence variations, 10 different types of ITS sequences were found (Fig. 3). These types are designated A through H (Table 1 and Fig. 3). The GenBank accession numbers of these types are shown in Table 1. Of these 10 types, 3 differ from each other only by the number of a run of C residues located between positions 574 and 584 (Fig. 2). The first one has 11 C residues, the second has 10, and the third has 9. Since this variation in the number of C residues could be due to sequencing errors, these three types are designated A-1, A-2, and A-3, respectively. Among the 24 isolates, 6 belong to type A-1, 5 belong to type A-2, 3 belong to type A-3; 3 (including the class 1 Downs strain) belong to type F, 2 belong to type G, and 1 each belongs to types B, C, D, E, and H (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Alignments of ITS sequences from 24 isolates. The consensus sequences of nucleotides found to be variable among the 24 isolates are shown with position numbers indicated. Bases of each isolate that are the same as for the consensus sequence are represented with asterisks, and the missing bases are denoted by hyphens. Isolate numbers are shown on the left. The type of each isolate is shown in parentheses next to the specimen numbers.

DISCUSSION

We have examined the ITS and the 5.8S rRNA gene sequences of 24 clinical isolates of H. capsulatum. The availability of the ITS and the 5.8S rRNA gene sequences of A. capsulatus made it possible for us to design primers to amplify this area. The amplified region includes the last 160 bp of ITS1, the entire 5.8S rRNA gene (159 bp), and the entire ITS2 (177 bp). The sequence of the 5.8S rRNA gene from the 24 isolates are identical, whereas ITS sequences are found to be variable at certain positions. When the sequences from different isolates are aligned, specific patterns are observed (Fig. 3). This is the basis for the typing method developed in this study.

ITS sequence variation has been used as a typing tool for several organisms, including Neisseria meningitidis (17), Acanthamoeba (24), Pseudomonas cepacia (14), Leptosphaeria maculans (27), and Pneumocystis carinii (15, 16). The results of this study indicate that ITS sequence variation can also be used to type H. capsulatum isolates. Although several typing methods have been described, none of them appears to be adequate for typing H. capsulatum isolates. The mtDNA RFLP technique classifies H. capsulatum into only four classes (23), and the yps-3 RFLP method types them into six classes (11). However, there have been five rDNA RFLP patterns identified within mtDNA class 2 isolates (21). The RAPD method types every isolate as a different type (12), suggesting that it is a method for fingerprinting, not for typing. The biallelic and multiallelic typing methods have similar problems. Every isolate from North America was found to have a different allelic pattern (5, 6). Furthermore, this method is very laborious, as 14 PCR runs have to be performed on each specimen in order to obtain a type (6). ITS typing requires only one nested PCR and one sequencing reaction. It types isolates by reading nucleotide sequences, not DNA banding patterns, on the gel, so there is much less ambiguity than with the RFLP typing.

In this study, four different types (A-1, A-2, A-3, and F) were found among the 12 isolates from Indianapolis. Isolates 21 and 22 from New York belonged to the same type (type G). All other isolates from any one city were different. The three isolates (numbers 15, 18, and 20) from Houston belonged to types B, E, and F, respectively. The two isolates (numbers 17 and 23) from Los Angeles were also different (types D and H). If types A-1, A-2, and A-3 are considered as the same (type A), type A is the predominant type in Indianapolis. Three isolates (isolates 4, 7, and 13) from three different cities (St. Louis, Birmingham, and New York) also belonged to type A. Since very few isolates from each of the other cities were examined in this study, it is not certain whether type A is prevalent in other cities.

The development of ITS typing may add a new tool for studying H. capsulatum isolates. This study is the first to classify Indianapolis isolates into four types. Although 10 types of H. capsulatum isolates were found, it is conceivable that additional types exist since the sample size of this study was quite small. Studies are in progress to correlate the results of ITS typing with those of other typing systems. The observation that the class 1 Downs strain is the same type as one Indianapolis and one Houston isolate, which presumably are class 2 isolates, suggests that ITS typing classifies H. capsulatum isolates differently from other typing systems. Since H. capsulatum undergoes sexual recombination in nature, we are also investigating whether ITS typing alone is sufficient to classify H. capsulatum isolates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armbruster C, Griess J, Setinek-Liska U. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis with liver and lung involvement outside the endemic area--differential diagnosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1996;108:210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellman B, Berman B, Sasken H, Kirsner R S. Cutaneous disseminated histoplasmosis in AIDS patients in south Florida. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:599–603. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodily K, Perfect J R, Procop G, Washington M K, Affronti J. Small intestinal histoplasmosis: successful treatment with itraconazole in an immunocompetent host. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:518–521. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell C C, Berliner M D. Virulence difference in mice of type A and B Histoplasma capsulatum yeasts grown in continuous light and total darkness. Infect Immun. 1973;8:677–678. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.4.677-678.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter D A, Burt A, Taylor J W, Koenig G L, White T J. Clinical isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum from Indianapolis, Indiana, have a recombining population structure. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2577–2584. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2577-2584.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter D A, Burt A, Taylor J W, Koenig G L, Dechairo B M, White T J. A set of electrophoretic molecular markers for strain typing and population genetic studies of Histoplasma capsulatum. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:1047–1053. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deodhare S, Sapp M. Adrenal histoplasmosis: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Source Diagnostic Cytopathol. 1997;17:42–44. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199707)17:1<42::aid-dc8>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gass M, Kobayashi G S. Histoplasmosis: an illustrative case with unusual vaginal and joint involvement. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:724–727. doi: 10.1001/archderm.100.6.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hajjeh R A. Disseminated histoplasmosis in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:S108–S110. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.supplement_1.s108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasuga T, Taylor J W, White T J. Phylogenetic relationship of varieties and geographical groups of the human pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum Darling. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:653–663. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.653-663.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keath E J, Kobayashi G S, Medoff G. Typing of Histoplasma capsulatum by restriction fragment length polymorphism in a nuclear gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2104–2107. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2104-2107.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kersulyte D, Woods J P, Keath E J, Goldman W E, Berg D E. Diversity among clinical isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum detected by polymerase chain reaction with arbitrary primers. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7075–7079. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7075-7079.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilby J M, Marques M B, Jaye D L, Tabereaux P B, Reddy V B, Waites K B. The yield of bone marrow biopsy and culture compared with blood culture in the evaluation of HIV-infected patients for mycobacterial and fungal infections. Am J Med. 1998;104:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostman J R, Edlind T D, LiPuma J J, Stull T L. Molecular epidemiology of Pseudomonas cepacia determined by polymerase chain reaction ribotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2084–2087. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2084-2087.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C H, Tang X, Jin S, Li B, Bartlett M S, Lundgren B, Helweg-Larsen J, Olsson M, Lucas S B, Roux P, Cargnel A, Atzori C, Matos O, Smith J W. Update on Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis typing based on nucleotide sequence variations in the internal transcribed spacer regions of rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:734–741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.734-741.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu J J, Bartlett M S, Shaw M M, Smith J W, Ortiz-Rivera M, Leibowitz M J, Lee C H. Typing of Pneumocystis carinii strains that infect humans based on nucleotide sequence variations of internal transcribed spacers of rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2904–2912. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2904-2912.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaughlin G L, Howe D K, Biggs D R, Smith A R, Ludwinski P, Fox B C, Tripathy D N, Frasch C E, Wenger J D, Carey R B, Hassan-King M, Vodkin M H. Amplification of rRNA loci to detect and type Neisseria meningitidis and other eubacteria. Mol Cell Probes. 1993;7:7–17. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1993.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raza J, Harris M T, Bauer J J. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Mt Sinai J Med. 1996;63:136–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin H, Furcolow M L, Yates J L, Brasher C A. The course and prognosis of histoplasmosis. Am J Med. 1959;27:278–288. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(59)90347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitzer E D, Keath E J, Travis S J, Painter A A, Kobayashi G S, Medoff G. Temperature-sensitive variants of Histoplasma capsulatum isolated from patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:258–261. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer E D, Lasker B A, Travis S J, Kobayashi G S, Medoff G. Use of mitochondrial and ribosomal DNA polymorphisms to classify clinical and soil isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1409–1412. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1409-1412.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan A A, Benson S M, Ewart A H, Hogan P G, Whitby R M, Boyle R S. Cerebral histoplasmosis in an Australian patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Med J Australia. 1998;169:201–202. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb140222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vincent R D, Goewert R, Goldman W E, Kobayashi G S, Lambowitz A M, Medoff G. Classification of Histoplasma capsulatum isolates by restriction fragment polymorphism. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:813–818. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.813-818.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vodkin M H, Howell D K, Visvesvara G S, McLaughlin G L. Identification of Acanthamoeba at the generic and specific levels using the polymerase chain reaction. J Protozool. 1992;39:378–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1992.tb01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vullo V, Mastroianni C M, Ferone U, Trinchieri V, Folgori F, Lichtner M, D'Agostino C. Central nervous system involvement as a relapse of disseminated histoplasmosis in an Italian AIDS patient. J Infect. 1997;35:83–84. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)91169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheat L J. Histoplasmosis: recognition and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:S19–S27. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.supplement_1.s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue B, Goodman P H, Annis S L. Pathotype identification of Leptosphaeria maculans with PCR and oligonucleotide primers from ribosomal internal transcribed spacers sequences. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1992;41:179–188. [Google Scholar]