Abstract

VACUTAINER PPT plasma preparation tubes were evaluated to determine the effects of various handling and shipping conditions on plasma human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) load determinations. Plasmas obtained from PPT tubes stored and shipped under nine different conditions were compared to conventional EDTA tube plasmas stored at −70°C within 2 h after phlebotomy. Compared to viral loads in frozen EDTA plasma, those in PPT tube plasma that was frozen immediately and either separated or shipped in situ were not significantly different. Viral loads in PPT tube plasma after storage for 6 h at either room temperature or 4°C, followed by shipment at ambient temperature or on wet or dry ice, were not significantly different from baseline viral loads in EDTA or PPT plasma. The results of this study indicate that the HIV load in PPT tube plasma is equivalent to that in standard EDTA plasma. Plasma viral load is not affected by storage or shipment temperature when plasma is collected in PPT tubes. Furthermore, plasmas can be shipped in spun PPT tubes, and the tubes provide a safer and more convenient method for sample collection and transport than regular EDTA tubes.

The level of virion-associated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RNA has been shown to be a prognostic marker of clinical disease (2, 11–14) and is used to predict clinical outcome early in infection, initiate antiviral therapy, and monitor response to treatment (2, 5, 6, 8, 10, 17). Thus, accurate and reliable quantitation of the virus is an essential part of the management of patients who become infected with HIV.

HIV loads, while highly predictive of a patient's clinical outcome, vary significantly between individuals irrespective of disease status and CD4 count (16). Furthermore, it is the increase or decline in the viral load in serially obtained samples, rather than the absolute copy number, which is most indicative of disease progression and response to therapy (3, 6, 8, 9, 15, 18). It is therefore highly important to minimize preanalytical variables caused by differences in sample handling and treatment.

Previous studies (7) (B. Yen-Lieberman, R. Carroll, C. Starkey, T. G. Spahlinger, and J. B. Jackson, Abstr. 34th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. I194, 1994) have shown that HIV-1 RNA levels are initially higher and more stable in plasma than in serum, that the viral load is unstable in whole blood (4), and that EDTA is preferred over heparin and ACD as an anticoagulant for samples used in PCR-based viral load assays (4).

These initial studies compared the stability of the HIV load collected in several kinds of blood collection tubes, and the sample handling protocol assessed the short-term, ambient-temperature stability of plasma viral loads in tubes processed within 2 h of collection and in tubes processed 8 and 30 h after collection. The present study expands on this earlier work by testing EDTA only as the anticoagulant of choice and determining the effect on viral load of shipping under three separate temperature conditions.

Becton Dickinson Vacutainer Systems (Franklin Lakes, N.J.) has developed a plastic evacuated tube for the collection of venous blood which, upon centrifugation, separates undiluted plasma for use in molecular diagnostic test methods. The tube has been modified from previously tested, prototype devices (7) to contain 9 mg of dried K2EDTA rather than sodium citrate. This modification yields a ratio of 1.8 mg of K2EDTA per ml of blood when the evacuated tube is filled correctly to its 5-ml draw volume. The tube also contains a material that, upon correct centrifugation (1,100 × g for 10 min), forms a barrier between the plasma and most of the cellular elements, allowing for transportation of the sample without first removing the plasma into secondary tubes. This study was conducted to determine optimal handling and shipping conditions for HIV plasma samples for viral load determinations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population.

Subjects of this study were consenting adults determined to be HIV positive by immunoassay or PCR. Study monitors were blinded with regard to patient status, CD4 count, drug therapy, sex, and date of diagnosis of infection.

Study protocol.

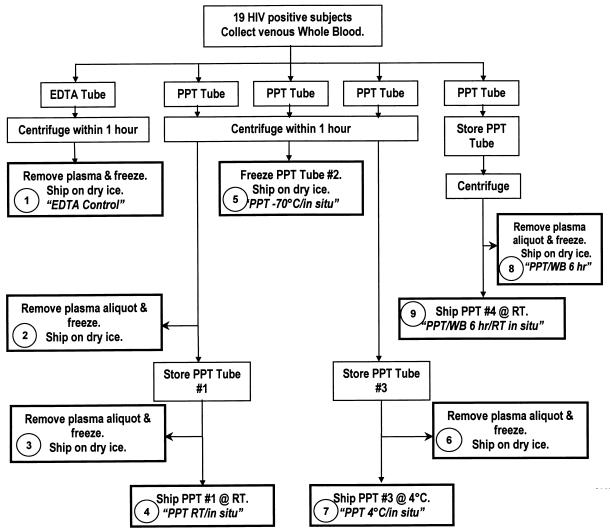

A schematic of the study protocol is depicted in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of study protocol. WB, whole blood.

Sample collection devices.

All sample collection tubes were obtained from Becton Dickinson and Company. VACUTAINER brand EDTA tubes were plastic, 6-ml-draw-volume, whole-blood tubes containing spray-dried K2EDTA with a Hemogard closure. VACUTAINER brand PPT plasma preparation tubes were plastic, 5-ml-draw-volume, whole-blood tubes with a Hemogard closure containing spray-dried K2 EDTA and a separator gel. PPT tubes are cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for use in molecular diagnostic tests.

Sample processing.

A summary of the sample processing, storage, and shipping conditions is given in Table 1. Briefly, venous whole blood was obtained from 19 consenting HIV-seropositive subjects who had viral loads of ≥5,000 RNA copies/ml. For each subject, blood was collected in one EDTA tube and four PPT tubes.

TABLE 1.

Summary and handling codes of processing, storage, and shipping conditions

| Code | Handling condition designation | Time as whole blood (h) | Plasma storage condition preshipping | Plasma shipping condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EDTA controla | 1 | −70°C | Dry ice |

| 2 | PPT control | 1 | −70°C | Dry ice |

| 3 | PPT RT/6 h | 1 | In situ,b 6 h, RT | Dry ice |

| 4 | PPT RT/in situ | 1 | In situ, 6 h, RT | In situ, RT |

| 5 | PPT −70°C/in situ | 1 | In situ, −70°C | In situ, dry ice |

| 6 | PPT 4°C/6 h | 1 | In situ, 6 h, 4°C | Dry ice |

| 7 | PPT 4°C/in situ | 1 | In situ, 6 h, 4°C | In situ, wet ice |

| 8 | PPT WB/6 h | 6 | −70°C | Dry ice |

| 9 | PPT WB/6 h/RT/in situ | 6 | In situ, 6 h, RT | In situ, RT |

A K2 EDTA tube was used. PPT tubes were used for all other handling conditions.

In situ, in the tube in which the blood was originally collected.

The EDTA tube and three PPT tubes were centrifuged at 1,100 × g for 10 min within 1 h of collection. Separated EDTA tube plasma, one full PPT tube (containing plasma), and separated PPT tube plasma were frozen at −70°C within 1 h of processing. Two PPT tubes containing plasma were held, one at room temperature (RT) and one at 4°C, for 6 h. One PPT tube containing whole blood was held on the bench at RT for 6 h and then centrifuged. Samples were then shipped overnight at ambient temperature or on wet or dry ice. Temperature monitors recorded internal shipping box temperatures overnight. Samples were then further processed the next day, when all samples were frozen at −70°C until they were assayed. The plasma viral load was determined by using the Roche Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor assay. The EDTA control was tested in duplicate.

Statistical analysis.

The logarithm transformation of the data was applied in order to stabilize the variances of responses to different handling conditions. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted by constructing clusters of group means in order to determine which ones were not statistically different. Correlation plots comparing viral loads obtained with each PPT tube handling condition to that obtained with the paired EDTA control (average of two measurements taken from the EDTA control tube) were constructed. The results for samples were excluded if they were above the linear range of the assay (750,000 RNA copies/ml). A regression analysis was performed, and the correlation coefficient (r) and equation of the line for each correlation plot was calculated. The coefficient of variation (CV) of the duplicate measurements from EDTA control tubes was obtained in order to validate the quality of the control data. The CV estimate for the two EDTA control tube measurements was calculated to be equal to 2.2%, which speaks in favor of the quality of the control data.

RESULTS

Correlation of PPT test results to results for EDTA tube controls.

Eight correlation plots comparing viral load measurements obtained in PPT tubes handled under various conditions to those obtained with EDTA control plasma were constructed. A summary of correlation data obtained from all eight correlation plots is given in the second and third columns of Table 2. Linear regression analysis of the data yielded Pearson's r2 values of 0.898 to 0.965, demonstrating that the log transformed viral load data fall on a straight line. The slope and intercept ranges were 0.9075 to 1.0366 and −0.011 to 0.389, respectively, indicating that the viral loads obtained with the PPT tubes were highly correlated and equivalent to those obtained with the EDTA tubes. These results indicate that viral loads obtained from plasma shipped in PPT tubes under all conditions studied are not statistically different from viral loads in EDTA plasma stored at −70°C within 2 h after phlebotomy and prior to analysis.

TABLE 2.

Correlation summary of regression analyses of EDTA control tube viral loads versus PPT tube viral loads and statistical analysis of viral load variability obtained with various handling conditions

| Handling condition designation (code) | Correlation plot summary, EDTA vs PPT tube

|

Statistical analysis of VL variability with each handling conditiona

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r2 | Regression line slope | Log10 avg VL | 95% CI | Lower limit of:

|

Upper limit of:

|

|||

| 95% CI | Clin. Indif. | 95% CI | Clin. Indif. | |||||

| PPT control (2) | 0.965 | 1.0099 | 4.868 | 0.379 | 4.489 | 4.368 | 5.246 | 5.368 |

| PPT RT/6 h (3) | 0.893 | 1.0128 | 4.913 | 0.401 | 4.512 | 4.413 | 5.314 | 5.413 |

| PPT RT/in situ (4) | 0.940 | 0.9075 | 4.831 | 0.386 | 4.445 | 4.331 | 5.216 | 5.331 |

| PPT −70°C/in situ (5) | 0.937 | 0.9427 | 4.898 | 0.373 | 4.525 | 4.398 | 5.272 | 5.398 |

| PPT 4°C/6 h (6) | 0.936 | 0.9226 | 4.923 | 0.349 | 4.573 | 4.423 | 5.272 | 5.423 |

| PPT 4°C/in situ (7) | 0.902 | 0.9683 | 4.960 | 0.355 | 4.606 | 4.460 | 5.315 | 5.460 |

| PPT WB/6 h (8) | 0.898 | 1.0366 | 4.995 | 0.389 | 4.606 | 4.495 | 5.385 | 5.495 |

| PPT WB/6 h/RT/in situ (9) | 0.918 | 0.9611 | 5.021 | 0.399 | 4.622 | 4.521 | 5.421 | 5.521 |

| EDTA control 1 (1) | 4.970 | 0.376 | 4.595 | 4.470 | 5.346 | 5.470 | ||

| EDTA control 2 (1) | 4.888 | 0.362 | 4.525 | 4.388 | 5.250 | 5.388 | ||

VL, viral load; CI, confidence interval; Clin. Indif., clinical indifference. 95% CI = log10 average viral load ± t(0.025, df) × standard error, where standard error = standard deviation/√n. The upper and lower limits of clinical indifference were determined by adding or subtracting 0.5 log unit from the log10 average viral load.

The 95% confidence intervals for the means for each handling condition, including the duplicate EDTA control measurements, are listed in the fifth column of Table 2. Lower and upper limits for this confidence interval were calculated by subtracting or adding the interval to the average viral load obtained for all samples subjected to each handling condition. The lower and upper confidence interval limits were then compared to the lower and upper limits of clinical indifference, respectively. Limits of clinical indifference were calculated by subtracting or adding 0.5 log unit to average viral loads obtained for all samples subjected to each handling condition. In each case, the confidence interval limits are well within the limits of clinical indifference, indicating that sample handling and shipping conditions in this study did not affect the clinical interpretation of viral load results.

Difference plots.

The correlation between viral loads in PPT tubes and EDTA controls was calculated by the method of Bland and Altman (1) by plotting the difference between PPT test values and the average of two EDTA control measurements against the average of PPT and EDTA control results. Eight difference plots, one for each handling condition, were constructed. In order to determine whether EDTA control and PPT tube viral load differences were related to viral load magnitude, regression analysis was performed on each difference plot. The slope was calculated for each regression line, and P values were calculated for the hypothesis of equality of the slope to zero. A summary of the data analysis for all difference plots is given in Table 3. All slopes for difference plot regression lines were indistinguishable from zero, as indicated by the P values, which were all <0.05. This indicates that there is no dependence of differences on viral copy number.

TABLE 3.

Results of difference plots comparing EDTA controls to PPT tubes handled under various conditions

| Code | Handling condition designation | Observations | Slope | P | Log10 Diffavga |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EDTA control | 17 | −0.0636 | 0.2881 | −0.0876 |

| 2 | PPT control | 17 | 0.0281 | 0.5746 | −0.0655 |

| 3 | PPT RT/6 h | 16 | 0.0711 | 0.4413 | −0.0379 |

| 4 | PPT RT/in situ | 15 | −0.0669 | 0.3503 | −0.0592 |

| 5 | PPT −70°C/in situ | 16 | −0.0266 | 0.7027 | −0.0467 |

| 6 | PPT 4°C/6 h | 16 | −0.7071 | 0.4932 | 0.0030 |

| 7 | PPT 4°C/in situ | 17 | 0.1934 | 0.8120 | 0.0564 |

| 8 | PPT WB/6 h | 16 | 0.0921 | 0.3102 | −0.1089 |

| 9 | PPT WB/6 h/RT/in situ | 14 | 0.0031 | 0.9710 | 0.0160 |

Diffavg, average difference.

DISCUSSION

The effects of eight handling conditions for samples in PPT tubes on viral loads in HIV-positive patients with viral loads greater than 5,000 copies/ml were assessed. In particular, the viral loads for each of the evaluation conditions were compared to results obtained with EDTA control tubes, and the effect of each handling condition on viral load stability was determined.

ANOVAs and multiple comparisons showed that the differences in viral load results between each of the handling conditions in PPT tubes and the EDTA control were not greater than the differences expected between two replicate EDTA tube samples. Confidence intervals for differences from control results were well within the ±0.5 log unit range of clinical indifference. Furthermore, statistical correlation analysis indicated that with respect to HIV viral load, plasma collected, processed, stored, and shipped in PPT tubes is indistinguishable from EDTA plasma frozen immediately after separation from whole blood.

In conclusion, the HIV viral load obtained from PPT tube plasma is equivalent to that in standard EDTA plasma. Whole blood can be collected in PPT tubes, held at room temperature for as long as 6 h after collection, and shipped as plasma overnight at ambient temperature or on wet or dry ice without affecting the HIV viral load. Furthermore, because whole blood can be collected in PPT tubes and processed into plasma that is shipped in situ, the PPT tube offers a closed sample collection system which is safer and more convenient than conventional EDTA tubes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vladimir Mats (Corporate Statistics Department, Becton Dickinson and Company) for providing the statistical analysis and interpretation of study data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bland J M, Altman D G. Comparing methods of measurement: why plotting against standard method is misleading. Lancet. 1995;346:1085–1087. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91748-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services and Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1998;47:45–47. . (Erratum, 47:619.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report of the NIH Panel to Define Principles of Therapy of HIV Infection. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1998;47:1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickover R, Herman S A, Saddiq K, Wafer D, Dillon M, Bryson Y J. Optimization of specimen-handling procedures for accurate quantitation of levels of human immunodeficiency virus RNA in plasma by reverse transcriptase PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1070–1073. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1070-1073.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrigan R. Measuring viral load in the clinical setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;10(Suppl. 1):S34–S40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holodniy M, Katzenstein D A, Israelski D M, Merigan T C. Reduction in plasma human immunodeficiency virus ribonucleic acid after dideoxynucleoside therapy as determined by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:1755–1759. doi: 10.1172/JCI115494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holodniy M, Mole L, Yen-Lieberman B, Margolis D, Starkey C, Carrol R, Spahlinger T, Todd J, Brooks Jackson J. Comparative stabilities of quantitative human immunodeficiency virus RNA in plasma from samples collected in VACUTAINER CPT, VACUTAINER PPT, and standard VACUTAINER tubes. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1562–1565. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1562-1566.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holodniy M, Mole L, Winters M, Merigan T C. Diurnal and short-term stability of HIV virus load as measured by gene amplification. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:363–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzenstein D A, Hammer S M, Hughes M D, Gundacker H, Jackson J B, Fiscus S, Rasheed S, Elbeik T, Reichman R, Japour A, Merigan T C, Hirsch M S. The relation of virologic and immunologic markers to clinical outcomes after nucleoside therapy in HIV-infected adults with 200 to 500 CD4 cells per cubic millimeter. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 175 Virology Study Team [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1091–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351502. . (Erratum, 337:1097, 1997.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katzenstein T L, Pederson C, Nielson C, Lundgren J D, Jakobsen P H, Gerstoft J. Longitudinal serum HIV RNA quantification: correlation to viral phenotype at seroconversion and clinical outcome. AIDS. 1996;10:167–173. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199602000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellors J W, Rinaldo C R, Jr, Gupta P, White R M, Todd J A, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1966;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellors J W, Munoz A, Giorgi J V, Margolick J B, Tassoni C J, Gupta P, Kingsley L A, Todd J A, Saah A J, Detels R, Phair J P, Rinaldo C R., Jr Plasma viral load and CD4+ lymphocytes as prognostic markers of HIV-1 infection [see comments] Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:946–954. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-12-199706150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellors J W, Rinaldo C R, Jr, Gupta P, White R M, Todd J A, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infections predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma [see comments] Science. 1996;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. . (Erratum, 275:14.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Brien W A, Hartigan P M, Martin D, Esinhart J, Hill A, Benoit S, Rubin M, Simberkoff M S, Hamilton J D. Changes in plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4+ lymphocyte counts and the risk of progression to AIDS. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on AIDS [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1996;334:426–431. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Brien W A, Hartigan P M, Daar E S, Simberkoff M S, Hamilton J D. Changes in plasma HIV RNA levels and CD4+ lymphocyte counts predict both response to antiretroviral therapy and therapeutic failure. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on AIDS [see comments] Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:939–945. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-12-199706150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Revets H, Marissens D, De Wit S, Lacor P, Clumeck N, Lauwers S, Zissis G. Comparative evaluation of NASBA HIV-1 RNA QT, AMPLICOR-HIV Monitor, and QUANTIPLEX HIV RNA assay, three methods for quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1058–1064. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1058-1064.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semple M, Loveday C, Weller I, Tedder R. Direct measurement of viraemia in patients infected with HIV-1 and its relationship to disease progression and zidovudine therapy. J Med Virol. 1991;35:38–45. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890350109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winters M A, Tan L B, Katzenstein D A, Merigan T C. Biological variation and quality control of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA quantitation by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2960–2966. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2960-2966.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]