Abstract

A variety of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) protocols for the molecular subtyping of Streptococcus pneumoniae have been reported; most are time-consuming and complex. We sought to modify reference PFGE protocols to reduce the time required while creating high-quality gels. Only protocol modifications that resulted in high-quality banding patterns were considered. The following protocol components were modified. Lysis enzymes (lysozyme, mutanolysin, and RNase A) were deleted in a stepwise fashion, and then the lysis buffer was deleted. Lysis and digestion were accomplished in a single step with EDTA and N-lauroyl sarcosine (ES; pH 8.5 to 9.3) incubation at 50°C in the absence of proteinase K. All enzymes except the restriction enzyme were omitted. A minimum incubation time of 6 h was required to achieve high-quality gels. All of the reactions were performed within 9 h, and the total protocol time from lysis to gel completion was reduced from 3 days to only 36 h. Combining lysis and digestion into a single step resulted in a substantial reduction in the time required to perform PFGE for S. pneumoniae. The ES solution may have caused cell lysis by activating N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase, the pneumococcal autolysin.

Molecular subtyping has revolutionized the field of infectious disease epidemiology. Molecular epidemiology allows the differentiation of isolates that appear identical by conventional methods, such as antimicrobial susceptibility testing or serotyping. While a variety of subtyping techniques have been developed, an ideal method would be simple to perform, be reproducible, and result in high-resolution banding patterns.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a significant public health concern, especially with the emergence of drug-resistant strains. Molecular epidemiology can be used to study the spread of drug-resistant S. pneumoniae in populations, making it an important adjunct for surveillance of this important pathogen. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), created by Schwartz, Cantor, and colleagues in 1982 (22), allows large DNA fragments to be separated on an agarose gel by virtue of their molecular weights. The electric field is sequentially changed at variable time intervals, or pulse times. The larger fragments take longer to realign in each field and thus move a shorter distance down the gel compared to the lower-molecular-weight fragments. Since the inception of PFGE, modifications have allowed the development of both field inversion gel electrophoresis (FIGE) and contour-clamped homogenous field electrophoresis (CHEF). CHEF has hexagonally arranged electrodes which cause movement of DNA fragments down a gel by alternating pulsed currents (21).

Commonly used methods for the molecular subtyping of S. pneumoniae include PFGE, BOX fingerprinting, restriction fragment end labeling, ribotyping, and PCR with primer enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence (ERIC2) (11). While the first three provide the most discrimination between strains, it has been suggested that BOX fingerprinting and restriction fragment end labeling are the best methods because of the quick turnaround time and ease of computer analysis. Restriction fragment end labeling can be completed in 48 h, while BOX fingerprinting requires 72 h to perform. Recently, amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis (AFLP) has been compared to PFGE in terms of time to completion and dendrogram analysis. While variation occurred in the dendrogram clusters, both protocols required approximately 2.5 days to complete, in addition to the 20 h required to perform PFGE (25). PFGE has been criticized for being time-consuming and labor-intensive. We sought to simplify existing S. pneumoniae PFGE protocols so as to create reproducible, high-quality gels with minimal time and effort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A Medline search was performed to identify S. pneumoniae PFGE protocols published from 1985 to 1998 (2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 13–17, 19, 23, 25, 26). Most protocols contained the following steps: bacterial cell suspension and agarose suspension, lysis, digestion, Tris-HCl–EDTA (TE) washes, enzyme restriction, and electrophoresis. We serially modified aspects of several published protocols to create a simplified method. Only changes which resulted in reproducible high-quality banding patterns were adopted. The standard protocol we used was as follows.

S. pneumoniae cultures were grown overnight on Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood (BBL) and suspended in 2 ml of cell suspension buffer (1 M NaCl–10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]) to an optical density of 1.3 to 1.5 at 450 nm. The bacterial suspension was mixed with an equal amount of 2% low-melting-point agarose (Sea Plaque; FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) and pipetted into 100-μl plug molds. After being solidified on ice for 10 min, the plugs were lysed by incubation with 2 ml of lysis buffer (1 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 6 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% Brij 58, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.5% N-lauroyl sarcosine [pH 7.6]) supplemented with 1 mg of lysozyme/ml–50 μg of RNase A/ml for 3 h at 37°C. Next, each plug was incubated with 2 ml of ES buffer (0.5 M EDTA–1% N-lauroyl sarcosine [pH 8.0 to 9.3]) and 100 μg of proteinase K/ml overnight at 50°C. The plugs were then washed three times with 10 ml of TE buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.6) at 37°C for 30 min each time. After preincubation of a 2- by 5-mm section of a plug in NE 4 buffer (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.) for 20 min, the DNA was digested with NE 4 buffer mixed with 30 U of SmaI and 200 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml at room temperature overnight. For ease of comparison, the run parameters from the modified protocol were used (5, 6, 13, 14, 16, 17, 22, 25, 26). The total time from lysis to gel completion was 3 days.

We performed PFGE on invasive penicillin-nonsusceptible S. pneumoniae (PNSP) strains from the Baltimore metropolitan area, collected as part of the Maryland Bacterial Invasive Disease Surveillance project (BIDS) (10). BIDS is a component of the multistate Emerging Infections Program that is coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Serotypes were determined by the quellung reaction with type-specific antiserum prepared at the CDC (4). Strains of serotypes 6A, 9V, 14, 19A, 19F, and 23F were chosen to provide a representative sample of PNSP isolates (12). Penicillin-susceptible isolates were also chosen from serotypes 9V, 23F, and 33F. A serotype 23F isolate, the multiresistant S. pneumoniae Spanish clone (Cleveland strain), was donated by A. Tomasz of Rockefeller University, New York, N.Y. (20).

RESULTS

Serial deletion of the lysis enzymes, including lysozyme, mutanolysin, and RNase A, caused no qualitative or quantitative changes in the banding pattern. The lysis step was deleted, and the digestion step was successfully performed in the absence of proteinase K. Lysis and digestion were completed in a single step with ES buffer (pH 8.0 to 9.3) at 50°C for 6 h. After the plug was washed three times in TE buffer, the DNA was digested by a 2-h incubation with 250 U of SmaI/ml mixed in NE 4 restriction buffer supplemented with 200 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml. The total protocol time from lysis to the end of electrophoresis was reduced to 36 h. While melting the agarose containing the DNA fragments at 62°C for 10 to 15 min is technically easier (13, 25), this resulted in sporadic loss of high-molecular-weight bands, increased lane background, and decreased overall intensity of the remaining bands.

Incubation with ES buffer with or without proteinase K (1 mg/ml) for less than 6 h did result in an identical banding pattern compared to that with the standard protocol. However, the bands were faint due to increased lane background, making interpretation more difficult. The addition of a second block of time to the gel run parameters allowed the improved resolution of bands between 50 and 100 kb and facilitated analysis of the gel. We did note that a small percentage of the organisms did not lyse during the first 6-h incubation; however, when these isolates were incubated a second time in the ES buffer overnight, adequate lysis did occur. The likelihood of complete lysis increased if we incubated only one plug in each tube of ES buffer.

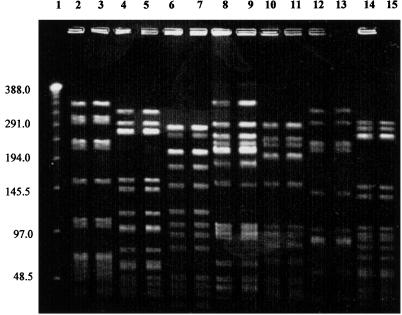

We were able to reproduce this simplified protocol in two laboratories. The plugs containing pneumococcal DNA still create reproducible banding patterns after 6 months of storage in TE buffer at 4°C. The final simplified protocol is as follows. S. pneumoniae cultures were grown overnight on Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood (BBL) and suspended in 2 ml of cell suspension buffer (1 M NaCl–10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]). The cell suspension was adjusted to an optical density of 1.3 to 1.5 at 450 nm. Equal amounts of bacterial suspension and 2% low-melting-point agarose (Sea Plaque) were mixed and pipetted into 100-μl plug molds. After the plugs were solidified on ice for 10 min, they were lysed and digested in one step. Each plug was incubated in 2 ml of ES buffer (pH 8 to 9.3) for 6 h at 50°C. The plugs were then washed three times with 10 ml of TE buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.6) at 37°C for 15 min each time. After preincubation of a 2- by 5-mm section of a plug in NE 4 restriction buffer for 15 min, the DNA was digested with NE 4 buffer mixed with 250 U of SmaI/ml and 200 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml at room temperature for 2 h. Each 1- by 5-mm section of plug was loaded into a 1% agarose gel, and PFGE was performed with CHEF DRIII at the following parameters: pulse times, 1 to 30 s for 19 h and 5 to 9 s for 8 h; 198 V; 1 liter/min; 14°C. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide for 20 min and captured on the Bio-Rad Gel Doc 2000 system. The PFGE banding patterns of PNSP isolates prepared by the standard protocol compared to the patterns of the same strains prepared by the simplified protocol are shown in Fig. 1. The simplified protocol reliably reproduces the banding pattern created with the standard protocol. Lane 9 (standard protocol) does have a faint band above 388 kbp which is not seen in lane 8 (simplified protocol). This band most likely represents unrestricted DNA. The PFGE patterns for the penicillin-susceptible isolates prepared with the simplified protocol and those with the standard protocol were also identical (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

PFGE of invasive S. pneumoniae isolates. Even-numbered lanes, simplified protocol; odd-numbered lanes, standard protocol. Lane 1, lambda ladder; lanes 2 and 3, serotype 6A; lanes 4 and 5, serotype 9V; lanes 6 and 7, serotype 19F; lanes 8 and 9, serotype 23F (Spanish clone); lanes 10 and 11, serotype 19A; lanes 12 and 13, serotype 14; lanes 14 and 15, serotype 9V.

DISCUSSION

A wide variety of methods are available for the molecular subtyping of infectious agents. In order to be useful, a technique must provide adequate discrimination of epidemiologically unrelated strains, result in gels with high-resolution, reproducible banding patterns within a short time; and be amenable to computer genetic relatedness analysis. Unfortunately, most of the methods available are labor-intensive and time-consuming.

PFGE has recently become an important method for determining microbial genetic relatedness. While it provides excellent intraspecies discrimination among a broad array of bacterial and fungal pathogens, it is time-consuming.

Our simplified protocol offers substantial advantages over published PFGE protocols for S. pneumoniae. By our method, any S. pneumoniae isolate can be optimally and efficiently subtyped on a high-quality gel within 36 h, thereby eliminating a key disadvantage of PFGE compared to BOX fingerprinting and restriction fragment end labeling.

The elimination of the lysis step and deletion of all enzymes except SmaI provides a simple, easy-to-use method for lysing S. pneumoniae. The lysis and digestion steps are accomplished with a two-reagent alkaline buffer. We did note that a small percentage of the organisms did not lyse during the first 6-h incubation; however, when these isolates were incubated a second time in the ES buffer overnight, adequate lysis did occur. The likelihood of complete lysis increased if we incubated only one plug in each tube of ES buffer. The need for endonuclease-free, filtered water is critical. Nonfiltered water can contain significant concentrations of bacteria and their accompanying RNA- and DNA-digesting enzymes. Without proteinase K, these enzymes could cause degradation of the S. pneumoniae isolate's DNA. Moreover, residual proteinase K affects the ability of the restriction enzyme to cut the DNA. The lack of proteinase K may have improved our ability to restrict more of the pneumococcal DNA, as the simplified protocol was not associated with the faint high-molecular-weight band seen with the standard protocol (Fig. 1, lane 9). The addition of a second block time on the CHEF DRIII and the avoidance of heating of the DNA-containing fragments reproducibly creates high-resolution banding patterns without any background lane intensity. The lysis and digestion steps are accomplished with a two-reagent alkaline buffer. S. pneumoniae undergoes autolysis by detergent activation of N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase (24). Perhaps N-lauroyl sarcosine, a detergent, causes autolysis by activation of pneumolysin (18).

There are other rapid PFGE protocols for gram-positive (8, 15, 17) and gram-negative (7) bacteria. Staphylococcus can be subtyped without proteinase K but requires lysostaphin (8). Many gram-negative rods can be subtyped without the lysis step but require digestion with proteinase K (1). To the best of our knowledge, no other protocol has been able to delete the lysis step and perform digestion without proteinase K. Future studies could address whether additional organisms could be subtyped with our simplified protocol. Moreover, this protocol restricted the pneumococcal DNA with SmaI. Restriction of pneumococcal DNA with additional enzymes, including ApaI, could be performed in future investigations. While the time to gel completion was diminished, the gels produced are often not of adequate quality (15) and may not have the same banding pattern as gels produced with standard protocols (17). In addition, the other protocols require multiple buffers and/or enzymes due to the lack of autolysins in most other bacteria (7, 15, 17). The unique ability of S. pneumoniae to undergo autolysis allows complete lysis and digestion without the addition of complex buffers or enzymes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participating hospital infection control practitioners and microbiology laboratory personnel of the Maryland Emerging Infections Program for identifying the pneumococcal cases and providing the bacterial isolates; Yvonne Dean-Hibbert and Lillian Billmann for assistance in conducting surveillance; Kim Holmes for assistance with data collection; and Althea Glenn for processing the isolates. We gratefully acknowledge Alexander Tomasz for the capsular type 23F Spanish-U.S. clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae. We also thank Jan Patterson, Victor Yu, and Judy Johnson for their assistance and guidance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D J, Kuhns J S, Vasil M L, Gerding D N, Janoff E N. DNA fingerprinting by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and ribotyping to distinguish Pseudomonas cepacia isolates from a nosocomial outbreak. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:648–649. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.648-649.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho C, Geslin P, Vaz Pato P V. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in France and Portugal. Pathol Biol. 1996;44:430–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doit C, Denamur E, Picard B, Geslin P, Elion J, Bingen E. Mechanisms of the spread of penicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae strains causing meningitis in children in France. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:520–528. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Facklam R R, Washington J A., II . Streptococcus and related catalase-negative gram-positive cocci. In: Balows A, Hausler W J Jr, Herrmann K L, Isenberg H D, Shadomy H J, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. pp. 238–257. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferroni A, Nguyen L, Gehanno P, Boucot I, Berche P. Clonal distribution of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae 23F in France. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2707–2712. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2707-2712.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasc A, Geslin P, Sicard A M. Relatedness of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroup 9 strains from France and Spain. Microbiology. 1995;141:623–627. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-3-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gautom R K. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other gram-negative organisms in 1 day. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2977–2980. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2977-2980.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goering R V, Winters M A. Rapid method for epidemiological evaluation of gram-positive cocci by field inversion gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:577–580. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.3.577-580.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall L M C, Whiley R A, Duke B, George R C, Efstratiou A. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of S. pneumoniae from the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:853–859. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.853-859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison L H, Ali A, Dwyer D M, Libonati J P, Reeves M W, Elliott J A, Billmann L, Lashkerwala T, Johnson J A. Relapsing group B streptococcal bacteremia in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:421–427. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-6-199509150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermans P W M, Sluijter M, Hoogenboezem T, Heersma H, van Belkum A, de Groot R. Comparative study of five different DNA fingerprint techniques for molecular typing of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1606–1612. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1606-1612.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann J, Cetron M S, Farley M M, Baughman W S, Facklam R R, Elliott J A, Deaver K A, Breiman R. The prevalence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Atlanta. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:471–476. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508243330803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefevre J C, Faucon G, Sicard A M, Gasc A M. DNA fingerprinting of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2724–2728. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2724-2728.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefevre J C, Gasc A M, Lemozy J, Sicard A M, Faucon G. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis for molecular epidemiology of penicillin resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. Pathol Biol. 1994;42:547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonard R, Carrol K. Rapid lysis of gram-positive cocci for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis using Achromopeptidase. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1997;6:288–291. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199710000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louie M, Louie L, Papia G, Talbot J, Lovgren M, Simor A E. Molecular analysis of the genetic variation among penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in Canada. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:892–900. doi: 10.1086/314664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matushek M G, Bonten M J M, Hayden M K. Rapid preparation of bacterial DNA for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2598–2600. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2598-2600.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merck and CoThe Merck index. An encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs, and biologicals, 12th ed. 1996. Monographs 8519 and 8782. Merck and Co., Inc. Whitehouse Station, N.J.

- 19.Moreno F, Crisp C, Jorgensen J, Patterson J. The clinical and molecular epidemiology of bacteremias at a university hospital caused by pneumococci not susceptible to penicillin. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:427–432. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz R, Coffey T J, Daniels M, Dowson C G, Laible G, Casal J, Hakenbeck R, Jacobs M, Musser J M, Spratt B G, Tomasz A. Intercontinental spread of a multiresistant clone of serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:302–306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 6.50–6.62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz D C, Saffran W, Welsh J, Haas R, Goldenberg M, Cantor C R. New techniques for purifying large DNAs and studying their properties and packaging. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1983;47:189–195. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1983.047.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soares S, Kristinsson K G, Musser J M, Tomasz A. Evidence for the introduction of a multiresistant clone of serotype 6B Streptococcus pneumoniae from Spain to Iceland in the late 1980s. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:158–163. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomasz A. The role of autolysins in cell death. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;235:439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb43282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Eldere J, Janssen P, Hoefnagels-Schuermans A, van Lierde S, Peetermans W E. Amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis for molecular typing of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2053–2057. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.2053-2057.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida R, Hirakata Y, Kaku M, Takemura H, Tanaka H, Tomono K, Koga H, Kohno S, Kamihira S. Trends of genetic relationship of serotype 23F penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Japan. Microbiology. 1997;43:232–238. doi: 10.1159/000239572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]