Abstract

Oligo-fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) facilitates precise chromosome identification and comparative cytogenetic analysis. Detection of autosomal chromosomes of Hippophaë rhamnoides has not been achieved using oligonucleotide sequences. Here, the chromosomes of five H. rhamnoides taxa in the mitotic metaphase and mitotic metaphase to anaphase were detected using the oligo-FISH probes (AG3T3)3, 5S rDNA, and (TTG)6. In total, 24 small chromosomes were clearly observed in the mitotic metaphase (0.89–3.03 μm), whereas 24–48 small chromosomes were observed in the mitotic metaphase to anaphase (0.94–3.10 μm). The signal number and intensity of (AG3T3)3, 5S rDNA, and (TTG)6 in the mitotic metaphase to anaphase chromosomes were nearly consistent with those in the mitotic metaphase chromosomes when the two split chromosomes were integrated as one unit. Of note, 14 chromosomes (there is a high chance that sex chromosomes are included) were exclusively identified by (AG3T3)3, 5S rDNA, and (TTG)6. The other 10 also showed a terminal signal with (AG3T3)3. Moreover, these oligo-probes were able to distinguish one wild H. rhamnoides taxon from four H. rhamnoides taxa. These chromosome identification and taxa differentiation data will help in elucidating visual and elaborate physical mapping and guide breeders’ utilization of wild resources of H. rhamnoides.

Keywords: Hippophaë rhamnoides L., oligo-FISH system, cytogenetic analysis, chromosomes, (TTG)6

1. Introduction

Hippophaë rhamnoides L. (Elaeagnaceae), also known as sea buckthorn, is a spiny deciduous shrub or small tree [1]. This species originated and migrated from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and adjacent regions [2]. Its natural habitats include severe environments with excessive salinity, drought, cold, and heat [3]. H. rhamnoides is known for its nutritional, medicinal, and ecological values [4]; it has been shown to improve the health of consumers. Moreover, its berries, which are edible, are used as a general body-toning agent [3]. H. rhamnoides, and its processed products, are potentially nontoxic when consumed by humans as a food or as a dietary supplement [5]. Thus, the ecological and commercial values of H. rhamnoides have drawn the attention of researchers for centuries [6]. Furthermore, an increase in its demand has prompted the fine breeding of various cultivars with genetic improvements to achieve high productivity and quality.

The systematic treatment of H. rhamnoides has been controversial. Studies have reported inconsistent findings with respect to the number of H. rhamnoides subspecies, for example, two subspecies [7], three subspecies [8], six subspecies [9], eight subspecies [10], and nine subspecies [11]. The treatment of Hippophaë rhamnoides ssp. sinensis Rousi has been supported by the findings of Rousi [10] and Bartish et al. [12]. To date, the WFO [13] has shown that H. rhamnoides comprises three accepted subspecies, four unresolved subspecies, and one accepted variety. H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis is an unresolved subspecies with one of the largest distribution ranges. Moreover, considering that abundant morphological variations have been described within the subspecies [12,14], it is critical to identify the genetic basis of these variations to facilitate the selection of superior cultivars from wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis.

Hippophaë rhamnoides taxa are often misidentified owing to similarities in their vegetative morphology. Furthermore, the fruits of different species are labeled with the same name and are primarily sold or used in dried form or as powders. Therefore, different taxa cannot be identified based on only morphological characteristics, and accurate identification methods are needed to avoid misidentification and misuse. All Hippophaë species have been successfully identified by DNA barcoding, and four H. rhamnoides subspecies have also been differentiated using ITS2 and psbA-trnH [15]. The male/female plants of H. rhamnoides have been identified using inter-simple sequence repeat [16] and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [17]. However, none of the other molecular cytogenetic technologies can be used to identify H. rhamnoides, thus limiting investigations on its identification and characterization.

Oligos designed from conserved DNA sequences from one species, particularly from part/whole/multiple chromosomes, can be precisely identified from genetically related species, thereby allowing comparative cytogenetic mapping of these species. These oligonucleotide sequences can then be readily produced and tagged with fluorescent markers for use as oligo-probes in FISH [18]. Species identification based on such oligo-probes has been reported in an increasing number of plant species, such as Avena L. species [19], Arachis hypogaea L. [20], Saccharum spontaneum L. [21], Citrus L. species [22], Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck × Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf., CC [23], Populus L. species [24], Strobus Opiz species [25], and Pinus L. species [26]. However, information regarding H. rhamnoides is limited. Chromosome identification remains a major challenge in H. rhamnoides with small chromosomes. In the present study, we aimed to use three oligo-probes––(AG3T3)3, 5S rDNA, and (TTG)6—to identify H. rhamnoides chromosomes simultaneously in a single round of FISH.

2. Materials and Methods

The seeds of five H. rhamnoides taxa were used in this study; three H. rhamnoides cultivars (‘Shenqiuhong’, ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, and ‘Wucifeng’) were collected from Hebei Province in China, one cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis was collected from Liaoning Province in China, and one wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis was collected from Sichuan Province in China.

2.1. Oligo-Probe Preparation

The probe of the telomere (AG3T3)3 repeat sequence 5′-AGGGTTTAGGGTTTAGGGTTT-3′ originated from Zea mays L. [27] and was developed in Berberis diaphana Maxim. and Berberis soulieana Schneid. [28], Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marsh., Syringa oblata Ait., Ligustrum lucidum Lindl., Ligustrum × vicaryi Rehder [29], Chimonanthus campanulatus R.H. Chang & C.S. Din [30], Juglan regia L. and Juglans sigillata Dode [31], and Hibiscus mutabilis L. [32]. The probe of the 5S rDNA fragment 5′-TCAGAACTCCGAAGTTAAGCGTGCTTGGGCGAGGTAGTAC-3′ was designed and developed in Piptanthus concolor Harrow ex Craib [33], Zanthoxylum armatum Candelle [34], B. diaphana and B. soulieana [28], F. pennsylvanica, S. oblata, L. lucidum, L. × vicaryi [29], Ch. campanulatus [30], J. regia and J. sigillata [31], and H. mutabilis [32]. The probe of the (TTG)6 trinucleotide repeat sequence 5′-TTGTTGTTGTTGTTGTTG-3′ was designed and developed in Avena L. species [35], F. pennsylvanica, S. oblata, L. lucidum, and L. × vicaryi [29]. All three oligo-probes were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and first tested in H. rhamnoides simultaneously in a single round of FISH. The oligo-probes were 5′-labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein or 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine.

2.2. FISH and Karyotype Analysis

Root tips were cut from H. rhamnoides seedlings and treated with nitrous oxide gas for 3 h, fixed in acetic acid for approximately 10 min, and finally preserved in 75% ethanol for further chromosome preparation. The root tip slides were prepared according to the method described by Luo et al. [33]. The meristematic zone (~1 mm) of the root tip was digested with pectinase and cellulase (Yakult Pharmaceutical Industry Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and then suspended; this suspension was used for slide preparation using the drop method. Chromosomes were denatured for 2 min at 80 °C and hybridized with oligo-probes for 2 h at 37 °C using the method described by Luo et al. [33]. After counterstaining with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) containing VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and covering with a coverslip, the slides were observed under an Olympus BX-63 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). FISH photomicrographs were obtained using a DP-70 CCD camera connected to the BX-63 microscope. Chromosome spreads in raw images were processed with DP Manager (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Photoshop CC 2015 (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA, USA). Approximately 90 mitotic metaphases or mitotic metaphase to anaphases from 30 slides of 15 H. rhamnoides root tips were observed. More than 10 cells in the mitotic metaphase or mitotic metaphase to anaphase with good chromosome spread were used to count the chromosomes. Three high-quality spreads were used for karyotype analysis. All chromosomes were aligned by length, from the longest to shortest. The chromosome ratio was determined as the length of the longest chromosome to that of the shortest chromosome.

3. Results

3.1. FISH-Enabled Visualization of H. rhamnoides Chromosomes

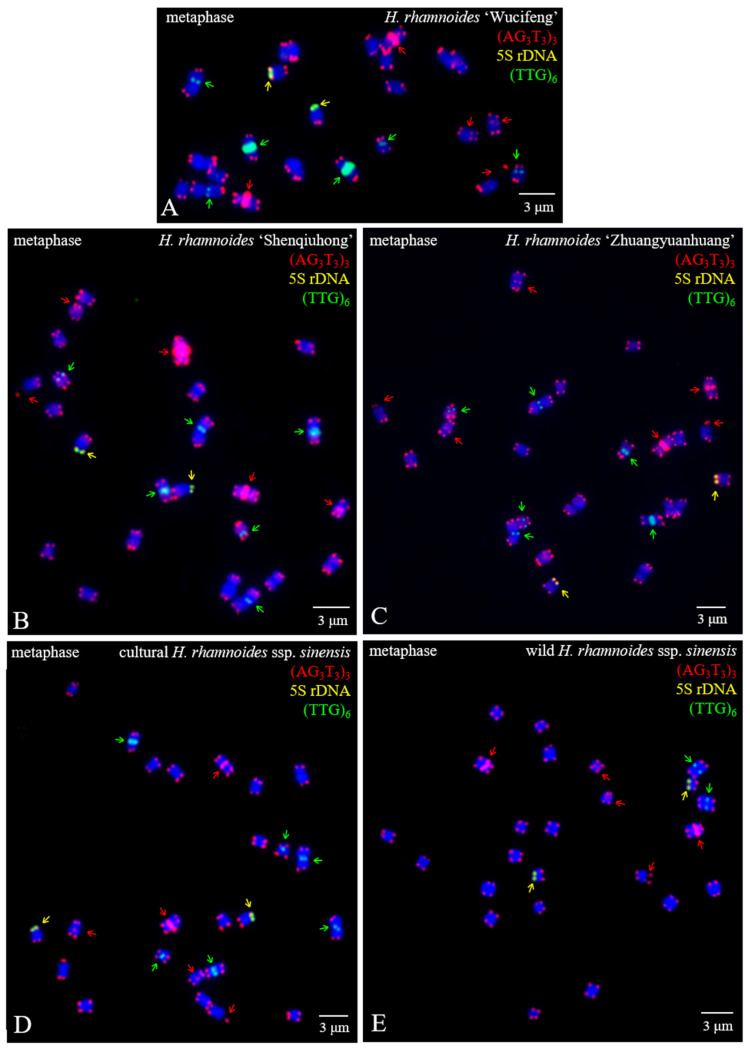

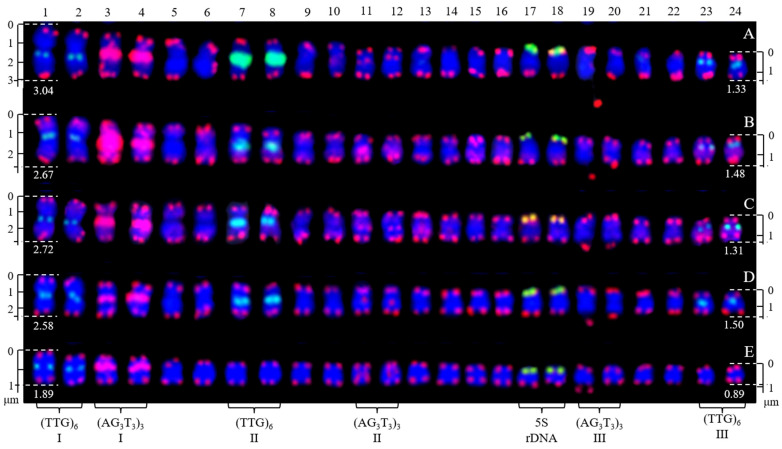

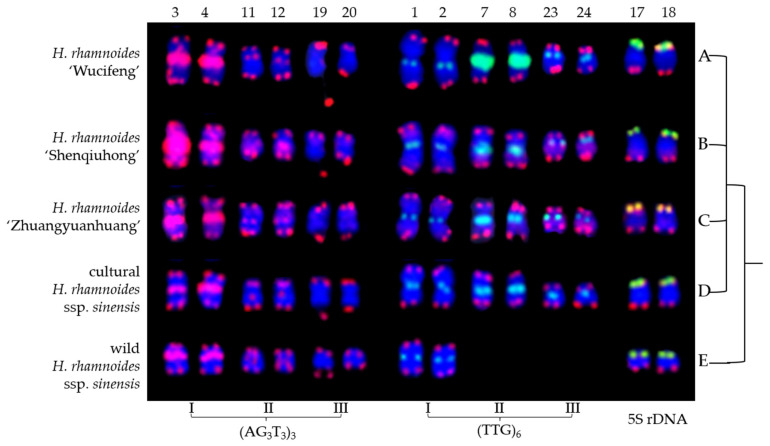

The mitotic metaphase of five H. rhamnoides taxa detected using (AG3T3)3, 5S rDNA, and (TTG)6 is illustrated in Figure 1. To visualize FISH signal distribution, each chromosome was cut from Figure 1 and aligned in Figure 2 based on its length and signal pattern. A total of 24 chromosomes were observed in each taxon of H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’ (Figure 1A and Figure 2A), H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’ (Figure 1B and Figure 2B), H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’ (Figure 1C and Figure 2C), cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis (Figure 1D and Figure 2D), and wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis (Figure 1E and Figure 2E). The chromosome size of each H. rhamnoides taxon was 1.33–3.04 μm for H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, 1.48–2.67 μm for H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, 1.31–2.72 μm for H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, 1.50–2.58 μm for cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, and 0.89–1.89 μm for wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. The size ranged from 0.89 to 3.03 μm, which is similar to that of small chromosomes. The ratio of the longest to shortest chromosomes in the mitotic metaphase was 3.40, indicating karyotype asymmetry in H. rhamnoides. Owing to the unclear centromeres of most chromosomes and their small size, the short and long arms of the chromosomes were not well characterized for further karyotype analysis.

Figure 1.

Mitotic metaphase chromosomes of Hippophaë rhamnoides detected using (AG3T3)3 (red), 5S rDNA (yellow), and (TTG)6 (green). (A) Hippophaë rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, (B) H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, (C) H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, (D) cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, and (E) wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. Red arrows show (AG3T3)3 located at the interstitial region of a chromosome or at the telomere region far away from the chromosome end, whereas yellow arrows show 5S rDNA and green show (TTG)6. (AG3T3)3 located at the chromosome end is not indicated with an arrow. The blue chromosomes were counterstained by DAPI. Scale bar = 3 μm.

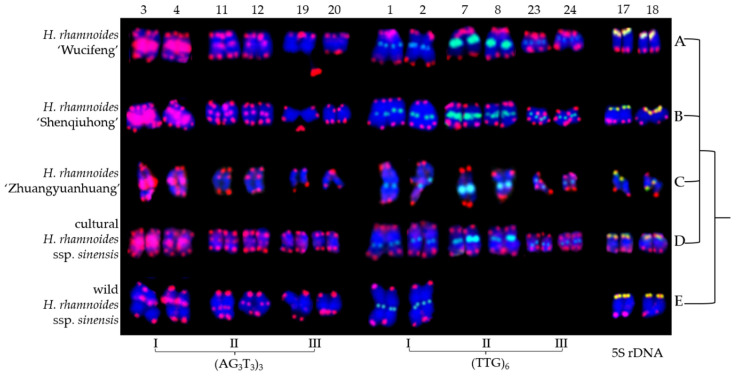

Figure 2.

Chromosomes from Figure 1 presented individually. The chromosomes were aligned by a combination of length from the longest to shortest and signal pattern. The left/right number represents the chromosome length: (A) H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, 3.04–1.33 μm; (B) H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, 2.67–1.48 μm; (C) H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, 2.72–1.31 μm; (D) cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, 2.58–1.50 μm; and (E) wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, 1.89–0.89 μm. The numbers on the top represent the chromosome numbers, whereas the bottom probes labeled some chromosomes: chromosomes 1/2, 7/8, 23/24 were labeled by (TTG)6 I (A–E), (TTG)6 II (A–D), and (TTG)6 III (A–D), whereas chromosomes 3/4, 11/12, and 19/20 were labeled by (AG3T3)3 I (A–E), (AG3T3)3 II (A–E), and (AG3T3)3 III (A–E); chromosomes 17/18 (A–E) were labeled by 5S rDNA.

(AG3T3)3 was located not only at the end of each chromosome but also at four chromosomally proximal regions (chromosomes 3/4/11/12); it was even dissociated from one end of chromosome 19 (satellite bodies) in five H. rhamnoides taxa (Figure 1). Two strong signals of (AG3T3)3 were observed in the proximal region of chromosome 3/4, whereas the other chromosomes showed minor differences in (AG3T3)3 signal intensity in five H. rhamnoides taxa (Figure 2). (TTG)6 was observed at six chromosomally proximal regions (chromosome 1/2/7/8/23/24) in three cultivars H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’ (Figure 1A and Figure 2A), H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’ (Figure 1B and Figure 2B), and H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’ (Figure 1C and Figure 2C) and one cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis (Figure 1D and Figure 2D), but only at two chromosomally proximal regions (chromosome 1/2) in wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis (Figure 1E and Figure 2E). Two strong signals of (TTG)6 were observed in the chromosomally proximal region of two chromosomes (chromosome 7/8) in three cultivars of H. rhamnoides (Figure 1A–C and Figure 2A–C) and one cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis (Figure 1D and Figure 2D), whereas the other chromosomes showed minor differences in (TTG)6 signal intensity in five H. rhamnoides taxa (Figure 1A–E and Figure 2A–E). The 5S rDNA nearly overlapped with (AG3T3)3 in two chromosome ends (chromosome 17/18) in five H. rhamnoides taxa (Figure 1A–E and Figure 2A–E), and the signal intensity showed minor differences.

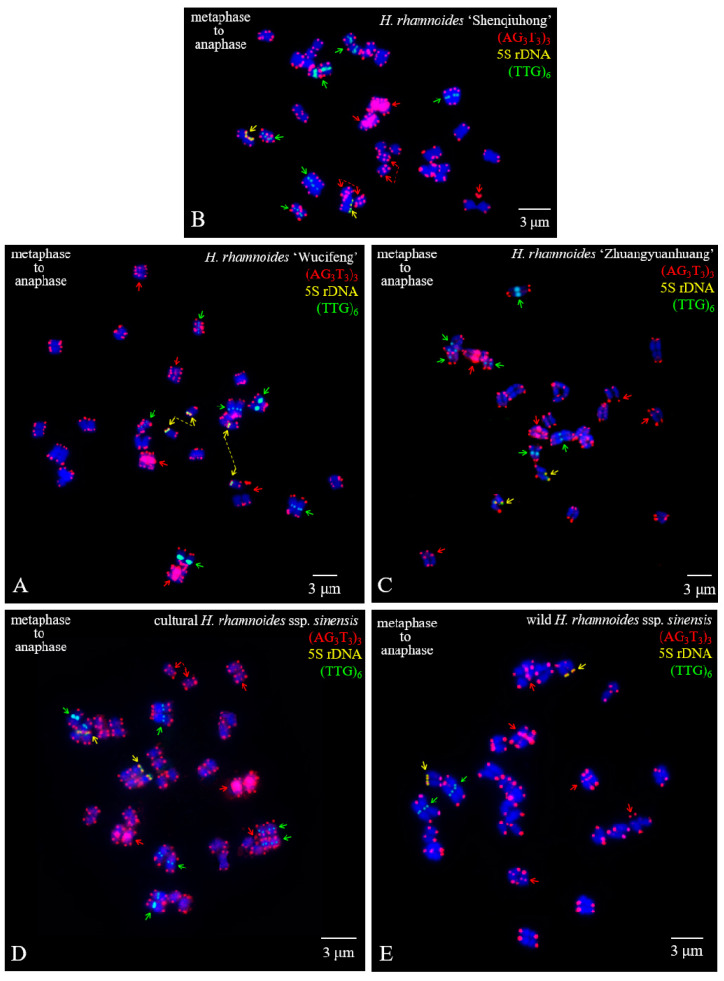

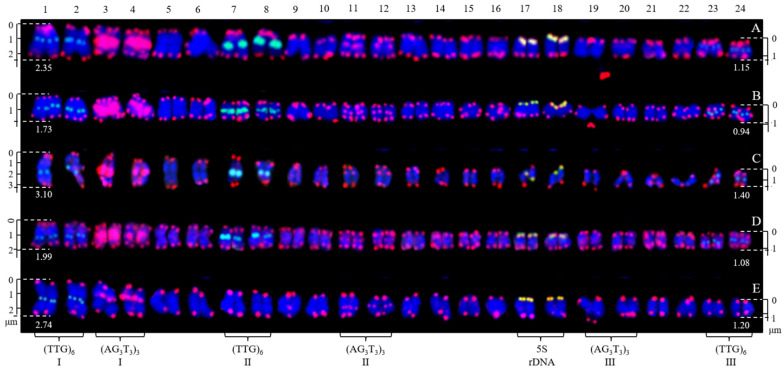

The mitotic metaphase to anaphase chromosomes of five H. rhamnoides taxa detected using (AG3T3)3, 5S rDNA, and (TTG)6 are illustrated in Figure 3. To clearly display FISH signal distribution, each chromosome was cut from Figure 3 and aligned in Figure 4 based on its length, signal pattern, and chromosome segregation. The chromosome size of each H. rhamnoides taxon was 1.15–2.35 μm for H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’ (Figure 3A and Figure 4A), 0.94–1.73 μm for H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’ (Figure 3B and Figure 4B), 1.40–3.10 μm for H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’ (Figure 3C and Figure 4C), 1.08–1.99 μm for cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis (Figure 3D and Figure 4D), and 1.20–2.74 μm for wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis (Figure 3E and Figure 4E). The size ranged from 0.94 to 3.10 μm, which is similar to that of small chromosomes. The ratio of the longest to shortest chromosomes in the mitotic metaphase to anaphase was 3.30, indicating karyotype asymmetry in H. rhamnoides. Due to chromosome segregation in the mitotic metaphase to anaphase, chromosome numbers in each taxon in Figure 3 ranged from 24 to 48. Several of them have been split into two separate chromosomes and far away at a certain distance (to make them easy to count, e.g., in Figure 3A,B,D, shown by the dotted line), whereas most of them were closely matched to each other (which makes it difficult to determine whether there is one or two chromosomes) in Figure 3. The signal number and intensity of (AG3T3)3, 5S rDNA, and (TTG)6 mitotic metaphase to anaphase chromosomes were nearly consistent with those of mitotic metaphase chromosomes if the two split chromosomes were integrated as one unit (Figure 4). Owing to the cryptic centromeres of several chromosomes and their small size, the short and long arms of the chromosomes were not well characterized for further karyotype analysis.

Figure 3.

Mitotic metaphase to anaphase chromosomes of Hippophaë rhamnoides detected using (AG3T3)3 (red), 5S rDNA (yellow), and (TTG)6 (green). (A) Hippophaë rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, (B) H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, (C) H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, (D) cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, and (E) wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. Red arrows show (AG3T3)3 located at the interstitial region of chromosomes or telomere region far away from the chromosome end, whereas yellow arrows show 5S rDNA and green arrows show (TTG)6. (AG3T3)3 located at the chromosome end has not been indicated with an arrow. Dotted lines connecting arrows represent two chromosomes split from one chromosome. We did not annotate all split chromosomes; we only annotated 4 chromosomes in Figure 3A (yellow dotted line), 4 chromosomes in Figure 3B (red dotted line), and 2 chromosomes in Figure 3D (red dotted line). The blue chromosomes were counterstained by DAPI. Scale bar = 3 μm.

Figure 4.

Chromosomes from Figure 2 presented individually. The chromosomes were aligned by a combination of length from the longest to shortest and signal pattern. The left/right number represents the chromosome length: (A) H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, 2.35–1.15 μm; (B) H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, 1.73–0.94 μm; (C) H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, 3.10–1.40 μm; (D) cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, 1.99–1.08 μm; and (E) wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, 2.74–1.20 μm. The numbers on the top represent the chromosome number, whereas the bottom probes labeled some chromosomes: chromosomes 1/2, 7/8, 23/24 were labeled by (TTG)6 I (A–E), (TTG)6 II (A–D), and (TTG)6 III (A–D); chromosomes 3/4, 11/12, 19/20 were labeled by (AG3T3)3 I (A–E), (AG3T3)3 II (A–E), and (AG3T3)3 III (A–E); and chromosomes 17/18 (A–E) were labeled by 5S rDNA.

3.2. Physical Map Distinguished Chromosomes

Next, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, the chromosomes were further eliminated with a common signal. As a result, the chromosomes of H. rhamnoides identified by (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA were aligned into a simplified version of Figure 3 and Figure 4. To better exhibit the centromere location, each chromosome was visualized in a black–white version (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The signal pattern ideograms were constructed based on the above black–white visualization of the chromosomes and their signal patterns in Figure 5 and Figure 6. A clear centromere location was observed in chromosomes 1/2, 3/4 in all five H. rhamnoides taxa. Generally, chromosome 3 of H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’ was seen as a dicentric chromosome (Figure 7). The chromosome 1/2, 3/4 arm ratio ranged from 1 to 1.7; hence, the two chromosomes have been designated as median region (m, 1 < r < 1.7). The symmetry of chromosome 1/2 was higher than that of chromosome 3/4. The centromere location was also observed for a few other chromosomes, such as chromosome 7/8, 19/20 of H. rhamnoides ’Zhuangyuanhuang’, albeit not as clearly as that of chromosomes 1/2, 3/4. It was difficult to determine the centromere location of other chromosomes as they were small in size and had lightly stained centromeres, which also made it difficult to count their arm ratios and construct a karyotype formula.

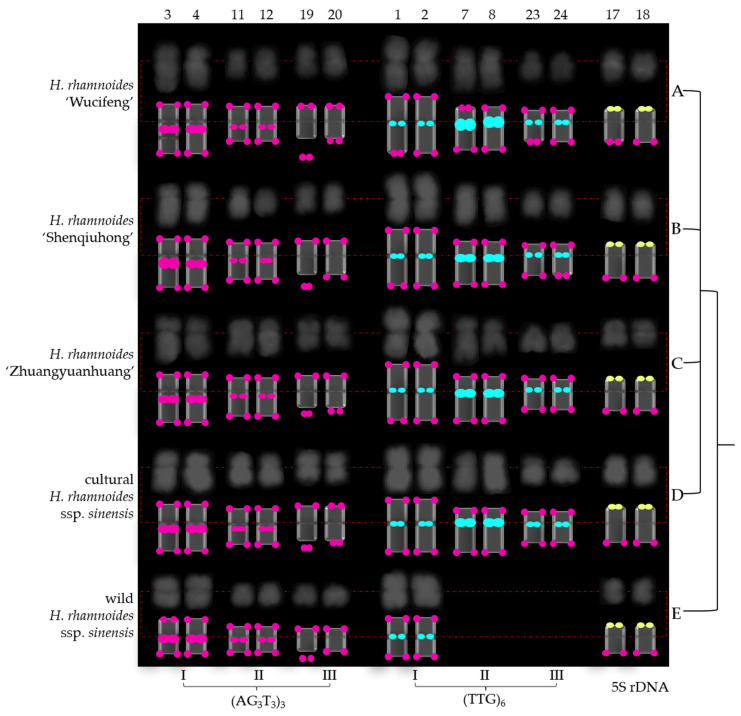

Figure 5.

Chromosomes of Hippophaë rhamnoides identified using (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA cut from Figure 3. (A) Hippophaë rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, (B) H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, (C) H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, (D) cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, and (E) wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. The numbers on the upper side represent the chromosome number consistent with H. rhamnoides in Figure 3. All chromosomes exhibited (AG3T3)3 end signals (red), whereas chromosome 3/4, 11/12 exhibited interstitial telomere repeat (AG3T3)3 I, (AG3T3)3 II signals in (A–E) (red), and chromosome 19 exhibited (AG3T3)3 III end signals far away from the chromosome ends in (A–E) (red). Chromosome 1/2 exhibited (TTG)6 I signal in (A–E) (green), whereas chromosome 7/8, 23/24 exhibited (TTG)6 II, (TTG)6 III signals in (A–D) (green). Chromosome 17/18 exhibited 5S rDNA signals in (A–E) (yellow). Figure 5 only exhibits chromosomes with (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA signals, exclusively identified chromosomes, whereas Figure 5 does not present chromosomes with no diagnostic chromosome signals, such as chromosomes only with (AG3T3)3 end signal. Therefore, Figure 5 is a simplified version of Figure 3.

Figure 6.

Chromosomes of Hippophaë rhamnoides identified using (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA cut from Figure 4. (A) Hippophaë rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, (B) H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, (C) H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, (D) cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, and (E) wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. The numbers on the upper side represent chromosome number consistent with H. rhamnoides in Figure 4. All chromosomes exhibited (AG3T3)3 end signals (red), whereas chromosome 3/4 and 11/12 exhibited interstitial telomere repeat (AG3T3)3 I, (AG3T3)3 II signals in (A–E) (red), and chromosome 19 exhibited (AG3T3)3 III end signals far away from the chromosome ends in (A–E) (red). Chromosome 1/2 exhibited (TTG)6 I signal in (A–E) (green), whereas chromosome 7/8, 23/24 exhibited (TTG)6 II, (TTG)6 III signals in (A–D) (green). Chromosome 17/18 exhibited 5S rDNA signals in (yellow). Figure 5 only exhibits chromosomes with (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA signals, exclusively identified chromosomes, whereas Figure 6 does not present chromosomes with no diagnostic chromosome signals, such as chromosomes only with (AG3T3)3 end signal. Therefore, Figure 6 is a simplified version of Figure 4.

Figure 7.

Physical map of Hippophaë rhamnoides. (A) Hippophaë rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, (B) H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, (C) H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, (D) cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, and (E) wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. In order to better exhibit the centromere location, each chromosome in black–white was another version of the chromosome in blue in Figure 5. The red dotted line indicates centromere location. Small chromosomes with dim centromere location were aligned by the subtle clues and traces of chromosome white/black contrast. Therefore, determination of their centromere location is difficult. The signal pattern ideograms were constructed based on the above black–white chromosome and signal patterns of chromosomes in Figure 5. The numbers on the upper side represent chromosome number, and the (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA signal types at the bottom are consistent with H. rhamnoides in Figure 5.

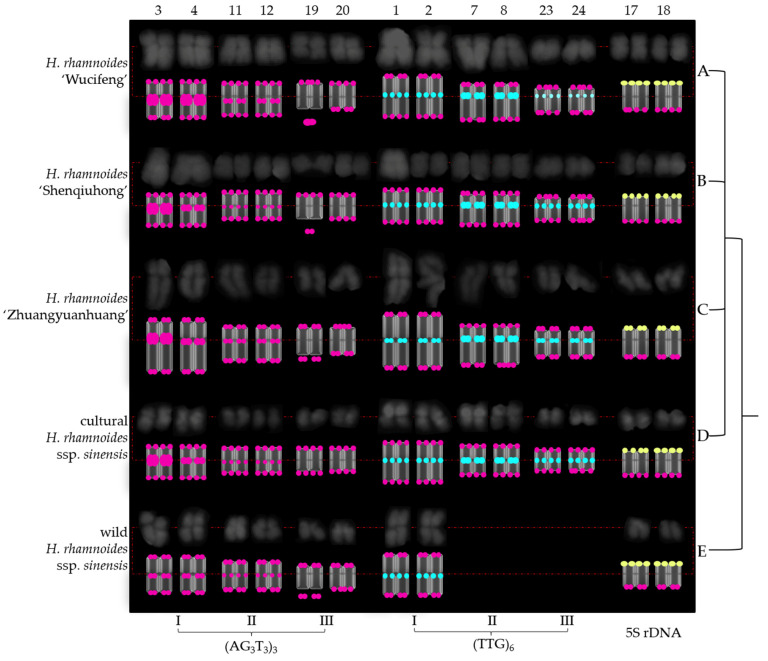

Figure 8.

Physical map of Hippophaë rhamnoides. (A) Hippophaë rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, (B) H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, (C) H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, (D) cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, and (E) wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. In order to better exhibit the centromere location, each chromosome in black–white was another version of the chromosome in blue in Figure 6. The red dotted line indicates centromere location. Small chromosomes with dim centromere location were aligned by the subtle clues and traces of chromosome white/black contrast. Therefore, determination of their centromere location is difficult. The signal pattern ideograms were constructed based on the above black–white chromosome and signal patterns of chromosomes in Figure 6. The numbers on the upper side represent chromosome number and the (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA signal types at the bottom are consistent with H. rhamnoides in Figure 6.

Owing to the lack of effective discernment, (AG3T3)3 located at the end of each chromosome was ignored here. Three (AG3T3)3 signal types identified six chromosomes of H. rhamnoides (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). Type I (AG3T3)3 discerned chromosome 3/4 by two strong signals in the proximal region. Type II (AG3T3)3 discerned chromosome 11/12 by two small signals in the proximal region. Type III (AG3T3)3 discerned chromosome 19 by a signal-dissociated chromosome end (satellite body). Chromosome 20 could not be discerned well based on its match with chromosome 19 (chromosome length, arm, centromere, and common signal).

(TTG)6 also showed three types of signal patterns (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). Type I (TTG)6 discerned chromosome 1/2 by two small signals in the proximal region in five H. rhamnoides taxa (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). Type II (TTG)6 discerned chromosome 7/8 by two strong signals in the proximal region in three cultivars H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’ (Figure 5A, Figure 6A, Figure 7A and Figure 8A), H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’ (Figure 5B, Figure 6B, Figure 7B and Figure 8B), and H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’ (Figure 5C, Figure 6C, Figure 7C and Figure 8C), and cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis (Figure 5D, Figure 6D, Figure 7D and Figure 8D). Type III (TTG)6 discerned chromosome 17/18 by two small signals in the proximal region (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). Consequently, (TTG)6 may distinguish wildtype H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis from three cultivars: H. rhamnoides ‘Wucifeng’, H. rhamnoides ‘Shenqiuhong’, and H. rhamnoides ‘Zhuangyuanhuang’, and cultural H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. Therefore, (AG3T3)3 and (TTG)6 are diverse and effective for chromosome recognition and taxon identification in H. rhamnoides. 5S rDNA discerned chromosome 17/18 by two small overlapping signals of (AG3T3)3 and 5S rDNA in one chromosome end (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). 5S rDNA only discerned two chromosomes that were conserved in five H. rhamnoides taxa.

Overall, (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA may discern 14 chromosomes in five H. rhamnoides taxa. More importantly, the combination of the three oligo-probes may identify one wild H. rhamnoides taxon from four H. rhamnoides cultivars.

4. Discussion

4.1. Karyotype Analysis

Chromosome number and morphological characteristics are important components of karyotypes. H. rhamnoides chromosomes in the mitotic metaphase are small (3.04–0.89 μm), and most of them showed a similar morphology in the current study. Owing to the small size of the chromosome and equivocal centromere of half chromosomes, we only measured total chromosome size here. The length of the long/short arm, karyotype, and cytotype, which are conventionally assessed in karyotype analysis, could not be determined in this study. Studies have reported the chromosome size of four Hippophaë taxa: 1.67–4.44 μm [36], 2.6–5.2 μm [37], and 0.97–2.77 μm [38] in H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis; 1.00–2.85 μm in H. rhamnoides L. ssp. turkestanica Rousi [38]; 0.77–2.84 μm in H. thibetana Schlechtend [38]; and 0.57–2.81 μm in H. neurocarpa S.W. Liu et T.N [38]. The chromosome size that we reported (0.89–3.03 μm) is within the range specified by previous studies on Hippophaë taxa (0.77–5.2 μm). Several chromosome sizes of other woody plants have been published: 1.05–1.81 μm in L. lucidum, 1.12–2.06 μm in F. pennsylvanica, 1.50–2.32 μm in S. oblata [29], 0.97–2.16 μm in J. regia [31], 1.23–2.34 μm in Z. armatum [34], 1.07–2.41 μm in Ch. campanulatus [30], 1.82–2.85 μm in B. diaphana [28], 1.18–3.0 μm in H. mutabilis [32], 1–4 μm in Citrus species [39], and 4.03–7.21 μm in P. concolor [33]. The chromosome size in our study (0.89–3.03 μm) is close to that of H. mutabilis (1.18–3.0 μm). Chromosome size is controlled by the chromosome phase when slide preparation is disturbed by measurements. As a result, chromosome size may be a guide for not only qualitative analysis (such as small chromosomes), but also quantitative analysis in chromosome research.

As observed in the present study, 24 chromosomes were counted in five H. rhamnoides taxa, which is in accordance with the known number (2n = 24) represented in older cytogenetic analyses [17,36,37,38,40,41,42,43], but different from the results (2n = 12) of Borodina [44] and Darmer [45]. This result (x = 12) is also in accordance with the known basic number ranging from 11 to 14 [46].

Satellite bodies, as hereditary features, may be used to identify chromosomes and distinguish species [47,48]. One pair of H. rhamnoides taxon satellite chromosomes was observed in previous studies [36,37,38], whereas Liang et al. [40] observed three pairs of H. rhamnoides subsp. sinensis satellite chromosomes. However, Li et al. [41] did not observe satellite chromosomes in H. rhamnoides taxon. Interestingly, only one satellite body was clearly observed in the present study. The possible reasons are as follows: (1) the other satellite body was too close to the chromosome arm to be well discovered; (2) the other satellite body was lost during slide preparation; (3) the H. rhamnoides chromosome was small in size, causing the satellite body to be smaller; (4) the satellite body is a fickle structure; hence, translocation and transfer of the satellite body occurs readily; and (5) the inconsistent evolution of two satellite bodies caused the other one to lack the portion that is visualized by oligo-probes. These possibilities may cause a change in the number of satellite bodies.

4.2. Role of (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA

(AG3T3)3, a classic chromosome end marker, is typically located in the distal region of the chromosome in H. mutabilis [32], J. regia, J. sigillata [31], F. pennsylvanica, S. oblata, L. lucidum, L. × vicaryi [28], B. diaphana, and B. soulieana [28]. Other similar types of (TxAyGz)n [49] have also been identified at each chromosome end in the woody plants C. sinensis × P. trifoliata [23], Citrus clementina Hort. Ex Tan. [50], Dendropanax morbiferus H. Lév., Eleutherococcus sessiliflorus (Rupr. Et Maxim.) Seem., Kalopanax septemlobus (Thunb. ex A.Murr.) Koidz [51], Ginkgo biloba L., Hordeum vulgare L., Phaseolus vulgaris sensu Blanco, non L. and Trigonella foenum-graecum L. [52], Rosa wichurana Cr‚p. [53], Cestrum elegans (Brongn. ex Neumann) Schltdl. [54], Pinus L. species [26], and Podocarpus L’Hér. ex Pers. species [55]. The (AG3T3)3 distal signal is generally ineffective in distinguishing chromosomes; however, it ensures chromosome integrity via a two-end signal, thereby guaranteeing accurate counts of chromosome number in previous studies. Similarly, in this study, (AG3T3)3 detected all chromosomes by FISH signal location at the chromosome termini and ensured the accuracy of chromosome counts of H. rhamnoides.

Occasionally, (AG3T3)3 or other similar types deviated from the end and were observed in the proximal and interstitial regions of chromosomes in the woody plant Ci. sinensis × P. trifoliata [23], Ch. campanulatus [30], Aralia elata (Miq.) Seem. [51], Pinus densiflora Siebold & Zucc. [52], R. wichurana [53], Cestrum parqui Benth. and Vestia foetida (Ruiz & Pav.) Hoffmanns. [56,57], and Podocarpus L. Her. ex Persoon species [55]. Furthermore, (AG3T3)3 dissociated from the chromosome (location satellite bodies) and was observed in Ch. campanulatus [30]. The distal, proximal, and dissociated signals of (AG3T3)3 have confirmed that it was easily distinguished in previous studies. Similarly, in this study, (AG3T3)3 detected six chromosomes by different FISH signal locations at the distal, proximal, and dissociated (location satellite bodies) chromosomes of H. rhamnoides.

(TTG)6, as a useful non-chromosome end marker, has demonstrated abundant variation in 16 Avena species [35], F. pennsylvanica, S. oblata, L. lucidum, and L. × vicaryi [29]. The signal location moved from the subterminal region to the proximal region, whereas the signal intensity ranged from weak and small to strong and large. The signal band on one chromosome ranged from one to more. Research on (TTG)n as an oligo-FISH marker is scarce. However, (TTG)10 has also emerged as an important microsatellite for genetic marker characterization in Capsicum annuum L. [58], Triticum aestivum L. [59], and Nicotiana tabacum L. [60]. In the present study, (TTG)6 sites in H. rhamnoides were relatively stable and were only located in the proximal region; nevertheless, the signal strength changed from weak to strong, similar to that in Avena species and Oleaceae species. Moreover, our results revealed variability in the number of (TTG)6 among H. rhamnoides taxa that showed divergence (two sites in wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis, but six sites in the other four H. rhamnoides cultivars), which also agreed with the varied (TTG)6 distribution among Avena species and Oleaceae species. Therefore, (TTG)6 is an effective oligo-FISH marker for detecting species or subspecies.

5S rDNA has been used extensively as a chromosome marker and exhibits substantial conservation and stability in woody plants Annona cherimola L. [61], C. sinensis × P. trifoliata [23], A. elata, D. morbiferus, E. sessiliflorus, K. septemlobus [51], Ch. campanulatus [30], G. biloba and P. densiflora [52], H. rhamnoides [17], R. wichurana [53], Passiflora species [62], Cestrum species [56], and V. foetida [57]. However, 5S rDNA has also showed high diversity in other plants, including A. hypogaea [20], Fragaria L. species [63], Crocus sativus L., Crocus vernus (L.) Hill [64,65], and P. concolor [33].

In the current study, 5S rDNA nearly colocalized with (AG3T3)3 at the two chromosome ends. Similar colocalization has been found in B. diaphana [28] and Chrysanthemum zawadskii (Herb.) Tzvel. [66]. Puterova et al. [17] also found two 5S rDNA terminal signals in H. rhamnoides chromosome, which supports the results of the present study. The 5S rDNA distribution in the termini has also been reported in F. pennsylvanica, S. oblata, L. lucidum, L. × vicaryi [29], and P. foetida [62]. The FISH results presented herein confirm a substantial conservation in the number and location of 5S rDNA among H. rhamnoides taxa. As a consequence, the present study results indicate that 5S rDNA cannot clearly distinguish H. rhamnoides taxa.

4.3. Detection of the X/Y-Chromosome in H. rhamnoides

The large X and small Y chromosomes in H. rhamnoides were revealed by Shchapov [43]. Another cytogenetic study on H. rhamnoides female karyotype without determination of sex chromosomes was conducted by Rousi and Arohonka [42]. However, Puterova et al. [17] successfully identified the X/Y-chromosome in H. rhamnoides using FISH from repetitive genomic DNA sequences. Unfortunately, we were unable to differentiate sex chromosomes and autosomes in the present study. Nevertheless, according to the previous analysis of chromosome spreads [17,38,43], the X-chromosome is one of the three longest pairs (chromosome 1–6), and the Y-chromosome is one of the five shortest pairs (chromosome 15–24). Considering the similar lengths of chromosomes 5/6 and 7/8 in the present study, the X-chromosome is one of the four longest pairs (chromosome 1–8) here. In addition, 5S rDNA is located in the autosome [17]. In the current FISH mapping, chromosomes 1/2, 7/8, and 23/24 showed (TTG)6 I, (TTG)6 II, and (TTG)6 III signals; chromosome 3/4 and 19/20 showed (AG3T3)3 I and (AG3T3)3 III signals; and chromosome 17/18 showed 5S rDNA signals. In other words, the X-chromosome was labeled by (TTG)6 I, (TTG)6 II, or (AG3T3)3 I, whereas the Y-chromosome was labeled by (TTG)6 III or (AG3T3)3 III. Previous work has also identified sex chromosomes using 5S rDNA and telomeric (CCCTAA)3 in Humulus japonicus Siebold & Zucc. [67], 5S rDNA, 45S rDNA, and the sex chromosome repetitive DNA sequences in Spinacia oleracea L. [68].

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess (AG3T3)3, (TTG)6, and 5S rDNA in H. rhamnoides. This study was conducted to identify the chromosomes of H. rhamnoides and compare cultural/wild H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis with three varieties of H. rhamnoides. Information on chromosome identification, as well as the identification of taxa, will not only help elucidate visual and elaborate physical mapping but will also guide breeders’ utilization of wild resources of H. rhamnoides. The use of the oligo-FISH system will enable, for the first time in the genomics era, a comprehensive cytogenetic analysis in H. rhamnoides. The results of this study will help identify chromosomes and establish physical maps of other Hippophaë taxa and close genera. We are committed to developing additional oligos (such as detection centromeres) to generate a high-resolution and informative cytogenetic map of the genome regions of H. rhamnoides.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yonghong Zhou for laboratory equipment.

Author Contributions

J.L. collected the materials and conducted the experiments. X.L. designed the oligo-probes, wrote the manuscript, provided funding, and supervised the study. Z.H. performed chromosome image analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 31500993).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are included in the form of graphs in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sharma B., Arora S., Sahoo D., Deswal R. Comparative fatty acid profiling of Indian sea buckthorn showed altitudinal gradient dependent species-specific variations. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2020;26:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s12298-019-00720-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia D.R., Abbott R.J., Liu T.L., Mao K.S., Bartish I.V., Liu J.Q. Out of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Evidence for the origin and dispersal of Eurasian temperate plants from a phylogeographic study of Hippophaë rhamnoides (Elaeagnaceae) New Phytol. 2012;194:1123–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonciu E., Olaru A.L., Rosculete E., Rosculete C.A. Cytogenetic study on the biostimulation potential of the aqueous fruit extract of Hippophaë rhamnoides for a sustainable agricultural ecosystem. Plants. 2020;9:843. doi: 10.3390/plants9070843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee Y.H., Jang H.J., Park K.H., Kim S.H., Kim J.K., Kim J.C., Jang T.S., Kim K.H. Phytochemical analysis of the fruits of sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides): Identification of organic acid derivatives. Plants. 2021;10:860. doi: 10.3390/plants10050860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang K., Xu Z., Liao X. Bioactive compounds, health benefits and functional food products of sea buckthorn: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021;3:2–12. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1905605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gâtlan A.M., Gutt G. Sea Buckthorn in plant based diets. An analytical approach of sea buckthorn fruits composition: Nutritional value, applications, and health Benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2021;18:8986. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18178986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avdeyev V.I. Novaya taxonomiya roda oblepikha: Hippophaë L. Izv. Akad. Nauk. Tadzhikskoy SSR Otd. Biol. Nauk. 1983;93:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Servettaz C. Monographie der Elaeagnaceae. Beih. Zum Bot. Cent. 1908;25:18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lian T.S., Chen X.L. Taxonomy of Genus Hippophaë L. [(accessed on 21 December 2021)];Hippophaë. 1996 9:15–24. Available online: http://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=2121204. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rousi A. The genus Hippophaë L. A taxonomic study. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 1971;8:177–227. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyvönen J. On phylogeny of Hippophaë (Eleagnaceae) Nordic. J. Bot. 1996;16:51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.1996.tb00214.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartish I.V., Jeppsson N., Nybom H., Swenson U. Phylogeny of Hippophaë (Elaeagnaceae) inferred from parsimony analysis of chloroplast DNA and morphology. Syst. Bot. 2002;27:41–54. doi: 10.1043/0363-6445-27.1.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WFO World Flora Online. 2021. [(accessed on 24 October 2021)]. Published on the Internet. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org.

- 14.Li H., Ruan C., Ding J., Li J., Wang L., Tian X. Diversity in sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides L.) accessions with different origins based on morphological characteristics, oil traits, and microsatellite markers. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0230356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y., Sun W., Liu C., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Song M., Fan G., Liu X., Xiang L., Zhang Y. Identification of Hippophaë species (Shaji) through DNA barcodes. Chin. Med. 2015;10:28–38. doi: 10.1186/s13020-015-0062-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das K., Ganie S.H., Mangla Y., Dar T.U., Chaudhary M., Thakur R.K., Tandon R., Raina S.N., Goel S. ISSR markers for gender identification and genetic diagnosis of Hippophaë rhamnoides ssp. turkestanica growing at high altitudes in Ladakh region (Jammu and Kashmir) Protoplasma. 2017;254:1063–1077. doi: 10.1007/s00709-016-1013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puterova J., Razumova O., Martinek T., Alexandrov O., Divashuk M., Kubat Z., Hobza R., Karlov G., Kejnovsky E. Satellite DNA and transposable elements in seabuckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides), a dioecious plant with small Y and large X chromosomes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017;9:197–212. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han Y., Zhang T., Thammapichai P., Weng Y., Jiang J. Chromosome-specific painting in Cucumis species using bulked oligonucleotides. Genetics. 2015;200:771–779. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.177642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang W., Jiang C., Yuan W., Zhang M., Fang Z., Li Y., Li G., Jia J., Yang Z. A universal karyotypic system for hexaploid and diploid Avena species brings oat cytogenetics into the genomics era. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21:213–227. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-02999-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu L., Wang Q., Li L., Lang T., Guo J., Wang S., Sun Z., Han S., Huang B., Dong W., et al. Physical mapping of repetitive oligonucleotides facilitates the establishment of a genome map-based karyotype to identify chromosomal variations in peanut. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21:107–118. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-02875-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng Z., Han J., Lin Y., Zhao Y., Lin Q., Ma X., Wang J., Zhang M., Zhang L., Yang Q., et al. Characterization of a Saccharum spontaneum with a basic chromosome number of x = 10 provides new insights on genome evolution in genus Saccharum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020;133:187–199. doi: 10.1007/s00122-019-03450-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He L., Zhao H., He J., Yang Z., Guan B., Chen K., Hong Q., Wang J., Liu J., Jiang J. Extraordinarily conserved chromosomal synteny of Citrus species revealed by chromosome-specific painting. Plant J. 2020;103:2225–2235. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng H., Tang G., Xu N., Gao Z., Lin L., Liang D., Xia H., Deng Q., Wang J., Cai Z., et al. Integrate and d karyotypes of diploid and tetraploid carrizo citrange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck x Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) as determined by sequential multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization with tandemly repeated DNA sequences. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:569–578. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xin H., Zhang T., Wu Y., Zhang W., Zhang P., Xi M., Jiang J. An extraordinarily stable karyotype of the woody Populus species revealed by chromosome painting. Plant J. 2020;101:253–264. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai Q., Zhang D., Liu Z.L., Wang X.R. Chromosomal localization of 5S and 18S rDNA in five species of subgenus Strobus and their implications for genome evolution of Pinus. Ann. Bot. 2006;97:715–722. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hizume M., Shibata F., Matsusaki Y., Garajova Z. Chromosome identification and comparative karyotypic analyses of four Pinus species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002;105:491–497. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-0975-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi Z.X., Zeng H., Li X.L., Chen C.B., Song W.Q., Chen R.Y. The molecular characterization of maize B chromosome specific AFLPs. Cell Res. 2002;12:63–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J., Luo X. First report of bicolour FISH of Berberis diaphana and B. soulieana reveals interspecific differences and co-localization of (AGGGTTT)3 and rDNA 5S in B. diaphana. Hereditas. 2019;156:13–20. doi: 10.1186/s41065-019-0088-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo X., Liu J. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of the locations of the oligonucleotides 5S rDNA, (AGGGTTT)3, and (TTG)6 in three genera of Oleaceae and their phylogenetic framework. Genes. 2019;10:375. doi: 10.3390/genes10050375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo X., Chen J. Physical Map of FISH 5S rDNA and (AG3T3)3 Signals displays Chimonanthus campanulatus R.H. Chang & C.S. Ding chromosomes, reproduces its metaphase dynamics and distinguishes its chromosomes. Genes. 2019;10:904. doi: 10.3390/genes10110904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo X., Chen J. Distinguishing Sichuan walnut cultivars and examining their relationships with Juglans regia and J. sigillata by FISH, early-fruiting gene analysis, and SSR analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:27–41. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo X., He Z. Distribution of FISH oligo-5S rDNA and oligo-(AGGGTTT)3 in Hibiscus mutabilis L. Genome. 2021;64:655–664. doi: 10.1139/gen-2019-0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo X., Liu J., Zhao A.J., Chen X.H., Wan W.L., Chen L. Karyotype analysis of Piptanthus concolor based on FISH with a oligonucleotides for rDNA 5S. Sci. Hortic. 2017;226:361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo X., Liu J., Wang J., Gong W., Chen L., Wan W. FISH analysis of Zanthoxylum armatum based on oligonucleotides for 5S rDNA and (GAA)6. Genome. 2018;61:699–702. doi: 10.1139/gen-2018-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo X., Tinker N.A., Zhou Y., Liu J., Wan W., Chen L. Chromosomal distributions of oligo-Am1 and (TTG)6 trinucleotide and their utilization in genome association analysis of sixteen Avena species. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018;65:1625–1635. doi: 10.1007/s10722-018-0639-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H.Z., Sheng L.X. Studies on karyotype of three sea buckthorn. J. Jilin Agr. Univ. 2011;33:628–631, 636. doi: 10.13327/jjjlau.2011.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y., Xu B.S. Karyotype Analysis of Hippophaë rhamnoides ssp. sinensis. [(accessed on 21 December 2021)];J. Wuhan Bot. Res. 1988 6:195–197. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=cjfd1988&filename=wzxy198802016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing M.S., Xue C.J., Li R.P. Karyotype analysis of sea buckthorn. J. Shanxi Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.). 1989;12:323–330. doi: 10.13451/j.cnki.shanxi.univ(nat.sci). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guerra M. Cytogenetics of Rutaceae. V. high chromosomal variability in Citrus species revealed by CMA/DAPI staining. Heredity. 1993;71:234–241. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1993.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang W.F., Li C.B., Lian Y.S. Karyotype Analysis of Four Sea Buckthorn in Qinghai. [(accessed on 21 December 2021)];Hippophaë. 1997 10:5–11. Available online: http://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=2814051. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X.L., Song W.Q., Chen R.Y. Studies on Karyotype of Some Berry Plants in North China. [(accessed on 21 December 2021)];J. Wuhan Bot. Res. 1983 11:289–293. Available online: http://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=1196583. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rousi A., Arohonka T. C-Band and Ploidy Level of Hippophaë rhamnoides. [(accessed on 21 December 2021)];Hereditas. 1980 92:327–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1980.tb01716.x. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19821606781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shchapov N.S. On the karyology of Hippophaë¨ rhamnoides L. Tsitol. Genet. 1979;13:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borodina N.A. Polutshenie isskustvennykh poliploidov oblepikhi. Bjull. Glavn. Bot. Sada. 1976;102:62–67. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darmer G. Rassenbildung bei Hippophaë rhamnoides (Sanddorn) Biol. Zentralbl. 1947;66:166–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arohonka A.T., Rousi A. Karyotypes and C-bands of Shepherdia and Elaeagnus. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 1980;17:258–263. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ris H., Kubai D.F. Chromosome structure. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1970;4:263–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.04.120170.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nebel B.R. Chromosome Structure. Bot. Rev. 1939;5:563–626. doi: 10.1007/BF02870166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peska V., Garcia S. Origin, diversity, and evolution of telomere sequences in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:117–125. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng H., Xiang S., Guo Q., Jin W., Cai Z., Liang G. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of genome-specific repetitive elements in Citrus clementina Hort. Ex Tan. and its taxonomic implications. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:77–87. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1676-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou H.C., Pellerin R.J., Waminal N.E., Yang T.J., Kim H.H. Pre-labelled oligo probe-FISH karyotype analyses of four Araliaceae species using rDNA and telomeric repeat. Genes Genom. 2019;41:839–847. doi: 10.1007/s13258-019-00786-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waminal N.E., Pellerin R.J., Kim N.S., Jayakodi M., Park J.Y., Yang T.J., Kim H.H. Rapid and efficient FISH using pre-labeled oligomer probes. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:8224–8233. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26667-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirov I.V., Van Laere K., Van Roy N., Khrustaleva L.I. Towards a FISH-based karyotype of Rosa L. (Rosaceae) Comp. Cytogenet. 2016;10:543–554. doi: 10.3897/compcytogen.v10i4.9536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peska V., Fajkus P., Fojtova M., Dvorackova M., Hapala J., Dvoracek V., Polanska P., Leitch A.R., Sykorova E., Fajkus J. Characterisation of an unusual telomere motif (TTTTTTAGGG)(n) in the plant Cestrum elegans (Solanaceae), a species with a large genome. Plant J. 2015;82:644–654. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray B.G., Friesen N., Heslop-Harrison J.S. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of Podocarpus and comparison with other gymnosperm species. Ann. Bot. 2002;89:483–489. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sykorova E., Lim K.Y., Fajkus J., Leitch A.R. The signature of the Cestrum genome suggests an evolutionary response to the loss of (TTTAGGG)n telomeres. Chromosoma. 2003;112:164–172. doi: 10.1007/s00412-003-0256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sykorova E., Lim K.Y., Chase M.W., Knapp S., Leitch I.J., Leitch A.R., Fajkus J. The absence of Arabidopsis-type telomeres in Cestrum and closely related genera Vestia and Sessea (Solanaceae): First evidence from eudicots. Plant J. 2003;34:283–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee J.M., Nahm S.H., Kim Y.M., Kim B.D. Characterization and molecular genetic mapping of microsatellite loci in pepper. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004;108:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1467-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma Z.Q., Röder M., Sorrells M.E. Frequencies and sequence characteristics of di-, tri-, and tetra-nucleotide microsatellites in wheat. Genome. 1996;39:123–130. doi: 10.1139/g96-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshioka Y., Matsumoto S., Kojima S., Ohshima K., Okada N., Machida Y. Molecular characterization of a short interspersed repetitive element from tobacco that exhibits sequence homology to specific tRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6562–6566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Falistocco E., Ferradini N. Advances in the cytogenetics of Annonaceae, the case of Annona cherimola L. Genome. 2020;63:357–364. doi: 10.1139/gen-2019-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Melo N.F., Guerra M. Variability of the 5S and 45S rDNA sites in Passiflora L. species with distinct base chromosome numbers. Ann. Bot. 2003;92:309–316. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcg138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qu M., Zhang L., Li K., Sun J., Li Z., Han Y. Karyotypic stability of Fragaria (strawberry) species revealed by cross-species chromosome painting. Chromosome Res. 2021;29:285–300. doi: 10.1007/s10577-021-09666-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmidt T., Heitkam T., Liedtke S., Schubert V., Menzel G. Adding color to a century-old enigma: Multi-color chromosome identification unravels the autotriploid nature of saffron (Crocus sativus) as a hybrid of wild Crocus cartwrightianus cytotypes. New Phytol. 2019;222:1965–1980. doi: 10.1111/nph.15715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frello S., Heslop-Harrison J.S. Repetitive DNA sequences in Crocus vernus Hill (Iridaceae): The genomic organization and distribution of dispersed elements in the genus Crocus and its allies. Genome. 2000;43:902–909. doi: 10.1139/g00-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abd El-Twab M.H., Kondo K. FISH physical mapping of 5S, 45S and Arabidopsis-type telomere sequence repeats in Chrysanthemum zawadskii showing intra-chromosomal variation and complexity in nature. Chromosome Bot. 2006;1:1–5. doi: 10.3199/iscb.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grabowska-Joachimiak A., Mosiolek M., Lech A., Góralski G. C-Banding/DAPI and in situ hybridization reflect karyotype structure and sex chromosome differentiation in Humulus japonicus Siebold & Zucc. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2011;132:203–211. doi: 10.1159/000321584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou J., Wang S., Yu L., Li N., Li S., Zhang Y., Qin R., Gao W., Deng C. Cloning and physical localization of male-biased repetitive DNA sequences in Spinacia oleracea (Amaranthaceae) Comp. Cytogenet. 2021;15:101–118. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v15i2.63061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are included in the form of graphs in this article.