Significance

Humoral immunity relies on the mutation and selection of B cells to better recognize pathogens. This affinity maturation process produces cells with diverse recognition capabilities. Examining optimal immune strategies that maximize the long-term immune coverage at a minimal metabolic cost, we show when the immune system should mount a de novo response rather than rely on existing memory cells. Our theory recapitulates known modes of the B cell response, predicts the empirical form of the distribution of clone sizes, and rationalizes as a trade-off between metabolic and immune costs the antigenic imprinting effects that limit the efficacy of vaccines (original antigenic sin). Our predictions provide a framework to interpret experimental results that could be used to inform vaccination strategies.

Keywords: B cell repertoire, affinity maturation, optimal decision theory, population dynamics

Abstract

In order to target threatening pathogens, the adaptive immune system performs a continuous reorganization of its lymphocyte repertoire. Following an immune challenge, the B cell repertoire can evolve cells of increased specificity for the encountered strain. This process of affinity maturation generates a memory pool whose diversity and size remain difficult to predict. We assume that the immune system follows a strategy that maximizes the long-term immune coverage and minimizes the short-term metabolic costs associated with affinity maturation. This strategy is defined as an optimal decision process on a finite dimensional phenotypic space, where a preexisting population of cells is sequentially challenged with a neutrally evolving strain. We show that the low specificity and high diversity of memory B cells—a key experimental result—can be explained as a strategy to protect against pathogens that evolve fast enough to escape highly potent but narrow memory. This plasticity of the repertoire drives the emergence of distinct regimes for the size and diversity of the memory pool, depending on the density of de novo responding cells and on the mutation rate of the strain. The model predicts power-law distributions of clonotype sizes observed in data and rationalizes antigenic imprinting as a strategy to minimize metabolic costs while keeping good immune protection against future strains.

Adaptive immunity relies on populations of lymphocytes expressing diverse antigen-binding receptors on their surface to defend the organism against a wide variety of pathogens. B lymphocytes rely on a two-step process to produce diversity: First, a diverse naive pool of cells is generated; upon recognition of a pathogen the process of affinity maturation allows B cells to adapt their B cell receptor (BCR) to epitopes of the pathogen through somatic hypermutation (1). This process, which takes place in germinal centers (2), can increase the affinity of naive BCR for the target antigen by up to a thousandfold factor (3). Through affinity maturation, the immune system generates high-affinity, long-lived plasma cells, providing the organism with humoral immunity to pathogens through the secretion of antibodies—the soluble version of the matured BCR—as well as a pool of memory cells with varying affinity to the antigens (4). However, the diversity and coverage of the memory pool, as well as the biological constraints that control its generation, have not yet been fully explored.

Analysis of high-throughput BCR sequencing data has revealed long tails in the distribution of clonotype abundances, identifying some very abundant clonotypes as well as many very rare ones (5, 6). Additionally, many receptors have similar sequences and cluster into phylogenetically related lineages (7–11). These lineages have been used to locally trace the evolution of antibodies in HIV patients (12, 13) and in influenza vaccinees (14, 15). Memory B cell clones are more diverse and less specific to the infecting antigen than antibody-producing plasma cells (16, 17). This suggests that the immune system is trying to anticipate infections by related pathogens or future escape mutants (18).

Theoretical approaches have attempted to qualitatively describe affinity maturation as a Darwinian coevolutionary process and studied optimal affinity maturation schemes (19–21), as well as optimal immunization schedules to stimulate antibodies with large neutralizing capabilities (22–24). Most of these approaches have been limited to short time scales, often with the goal of understanding the evolution of broadly neutralizing antibodies. Here we propose a mathematical framework to explore the trade-offs that control how the large diversity of memory cells evolves over a lifetime.

Despite long-lasting efforts to describe the coevolution of pathogens and host immune systems (25–29) and recent theoretical work on optimal schemes for using and storing memory in the presence of evolving pathogens (30), few theoretical works have described how the B cell memory repertoire is modified by successive immunization challenges. Early observations in humans (31) have shown that sequential exposure to antigenically drifted influenza strains was more likely to induce an immune response strongly directed toward the first strain the patients were exposed to (32). This immune imprinting with viral strains encountered early in life was initially called “original antigenic sin” as it can limit the efficiency of vaccination (33). This phenomenon has been observed in a variety of animal models and viral strains (34). Secondary infections with an antigenically diverged influenza strain can reactivate or “backboost” memory cells specific to the primary infecting strain (35). This response is characterized by lower binding affinity but can still have in vivo efficiency thanks to cross-reactive antibodies (36, 37). There is a long-standing debate about how detrimental original antigenic sin is (38, 39). Under what conditions should the immune system invest in keeping an antibody memory of past infections, as opposed to responding de novo to each new infection? When developing memory is preferred to responding de novo, how diverse should that memory be?

We build a theoretical framework of joint virus and repertoire evolution in antigenic space and investigate how acute infections by evolving pathogens have shaped, over evolutionary time scales, the B cell repertoire response and reorganization. Pathogens causing acute infections may be encountered multiple times over time scales of years, especially when they show a seasonal periodicity, while the maturation processes in the B cell repertoire take place over a few weeks. This observation allows us to consider that affinity maturation happens in a negligible time with respect to the reinfection period. Within this approximation, we investigate the optimal immune maturation strategies using a framework of discrete time decision process. We show the emergence of three regimes—monoclonal memory response, polyclonal memory response, and a de novo response—as trade-offs between immune coverage and resource constraint. Additionally, we demonstrate that reactivation of already existing memory clonotypes can lead to self-trapping of the immune repertoire to low reactivity clones, opening the way for original antigenic sin.

Results

Affinity Maturation Strategies for Recurring Infections.

B cells recognize pathogens through the binding of their BCR to parts of the pathogen’s proteins, called epitopes, which we refer to as “antigens” for simplicity. To model this complex protein–protein interaction problem, we assume that both receptors and antigens may be projected into an effective, d-dimensional antigenic space (Fig. 1), following the generalized shape space idea pioneered by Perelson and Oster (40). Receptor–antigen pairs at close distance in that space bind well, while those that are far away bind poorly. Specifically, we define a cross-reactivity function quantifying the binding affinity between antigen a and receptor x, which we model by a stretched exponential, . This choice of function is the simplest that allows for introducing a cross-reactivity radius, r0, while controlling how sharply recognition is abrogated as the distance between antigen and receptor oversteps that radius, through the stretching exponent q.

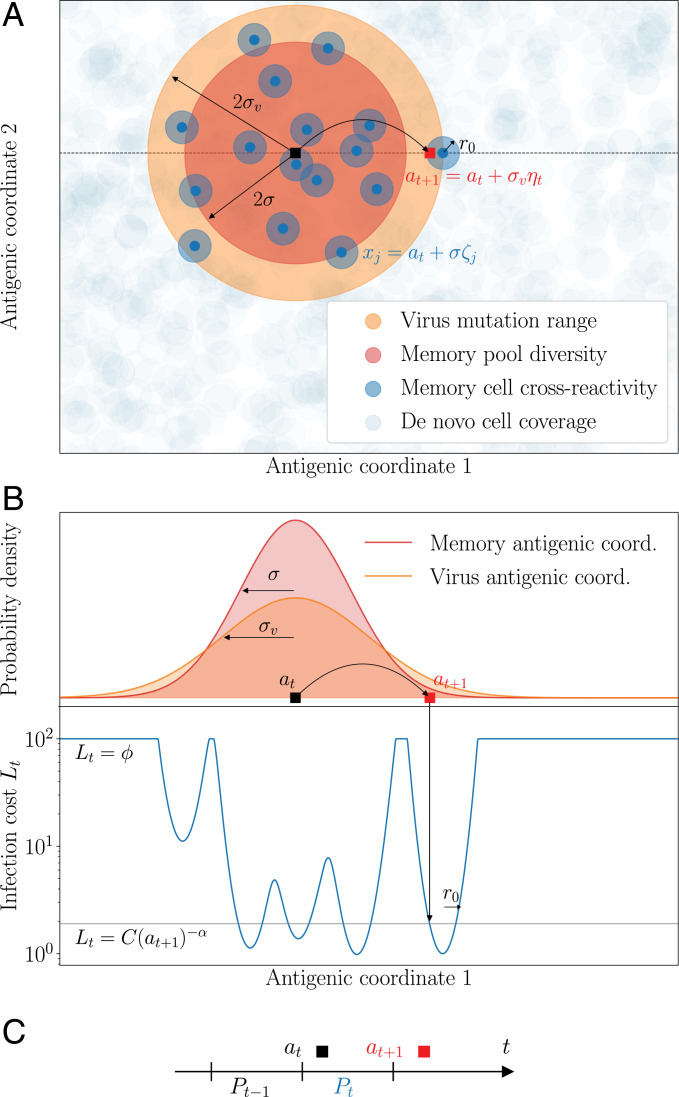

Fig. 1.

Model of sequential affinity maturation. (A) An infecting strain is defined by its position an in antigenic space (dark square). In response, the immune system creates m new memory clonotypes xj (blue points) from a Gaussian distribution of width σ centered in at (red area). These new clonotypes create a cost landscape (blue areas) for the next infection, complemented by a uniform background of naive, innate, and T cells (basal coverage, light blue). The next infecting strain (red square) is drawn from a Gaussian distribution of width σv centered in at (orange area). The position of this strain on the infection landscape is shown with the arrow. Antigenic space is shown in two dimensions for illustration purposes but can have more dimensions in the model. (B) Cross-section of the distributions of memories and of the next strain, along with the infection cost landscape Lt (in blue). Memories create valleys in the landscape, on a background of baseline protection . (C) Sequential immunization. Strain at modifies the memory repertoire into Pt, which is used to fight the next infection . Pt is made of all newly created clonotypes (blue points in A) as well as some previously existing ones (not shown). Clonotype abundances are boosted following each infection as a function of the cross-reactivity, and each individual cell survives from one challenge to the other with a probability γ.

For simplicity, we focus on a single pathogen represented by its immunodominant antigen, so that each viral strain is represented by a single point at in antigenic space (black square), where is a discrete time counting the number of reinfections. It is difficult to estimate the rate of reinfections or exposures to the same pathogen. It can be fairly high in humans, where individuals are exposed to the most common viruses from less than once to several times a year (41). The numbers of lifetime exposures would then range from a few to a few hundred.

The B cell repertoire, on the other hand, is represented by a collection of antigenic coordinates corresponding to each receptor clonotype. We distinguish memory cells (dark blue circles in Fig. 1A), denoted by Pt, which have emerged in response to the presence of the virus, and a dense background of naive and innate cells N (light blue circles), which together provide a uniform but weakly protective coverage of any viral strain (subsumed into the parameter defined later in this section).

The viral strain evolves randomly in antigenic space, sequentially challenging the existing immune repertoire. This assumption is justified by the fact that for acute infections with a drifting viral strain, such as influenza, the immune pressure exerted on the strain does not happen in hosts but rather at the population level (25). Viral evolution is not neutral, but it is unpredictable from the point of view of individual immune systems. Specifically, we assume that upon reinfection, the virus is represented by a new strain, which has moved from the previous antigenic position at to the new one according to a Gaussian distribution with typical jump size σv, called “divergence” (Materials and Methods).

Upon infection by a viral strain at at, available cross-reactive memory or naive cells will produce antibodies whose affinities determine the severity of the disease. We quantify the efficiency of this early response to the strain at with an infection cost It:

| [1] |

where is a maximal cost corresponding to using a de novo response and where denotes the size of clonotype x at time t. This infection cost is a decreasing function of the coverage of the virus by the preexisting memory repertoire, , with a power α governing how sharp that dependence is. Intuitively, the lower the coverage, the longer it will take for memory cells to mount an efficient immune response and clear the virus, incurring larger harm on the organism (42, 43).

When memory coverage is too low, the response of the naive B cell repertoire and the rest of the immune system, including its innate branch as well as T cell cytotoxic activity, offer protection through a de novo response, incurring a maximal cost fixed to . Memory cells respond more rapidly than naive cells, which is indirectly encoded in our model by the de novo cost being larger than the cost when specific memory cells are present (of order 1 or less). In SI Appendix, we show how this de novo cutoff may be derived in a model where the immune system activates its memory and de novo compartments in response to a new infection, when, for example, naive clonotypes are very numerous but offer weak protection. In that interpretation, scales like the inverse density of naive cells. We will refer to as “de novo density,” keeping in mind that this basal protection levels also includes other arms of the immune system. In Fig. 1B, we plot an example of the infection cost along a cross-section of the antigenic space.

After this early response, activated memory cells proliferate and undergo affinity maturation to create new plasma and memory cells targeting the infecting strain. To model this immune repertoire reorganization in response to a new infection at, we postulate that its strategy has been adapted over evolutionary time scales to maximize the speed of immune response to subsequent challenges, given the resource constraints imposed by affinity maturation (42). This strategy dictates the stochastic rules according to which the BCR repertoire evolves from to Pt as a result of affinity maturation (Fig. 1C).

We consider the following rules inspired by known mechanisms available to the immune system (2). After the infection by at has been tackled by existing receptors and the infection cost has been paid, new receptors are matured to target future versions of the virus. Their number mt is distributed according to a Poisson law, whose mean is controlled by the cost of infection, . This dependence accounts for the feedback of the early immune response on the outcome of affinity maturation, consistent with extensive experimental evidence of the history dependence of the immune response (44). Each new receptor is roughly located around at in antigenic space with some added noise and starts with clonotype size by convention. The diversification parameter σ can be tuned by the immune system through the permissiveness of selection in germinal centers, through specific regulation factors induced at the early stage of affinity-based selection (45): σ = 0 means that affinity maturation only keeps the best binders to the antigens, while means that selection is weaker.

At the same time, each clonotype from the previous repertoire may be reactivated and be subsequently duplicated through cell divisions (18), with probability (Materials and Methods), proportional to the cross-reactivity, where is a proliferation parameter. These previously existing cells and their offspring may then die before the next infection. We denote by γ their survival probability, so that the average lifetime of each cell is . The proliferation and death parameters μ and γ are assumed to be constrained and fixed. The net mean growth is thus given by . is defined as the maximum growth factor. At the end of the process, the updated repertoire Pt combines the result of this proliferation and death process applied to with the new receptors obtained from affinity maturation.

To assess the performance of a given strategy, we define an overall cost function at each time step:

| [2] |

The second term corresponds to a plasticity cost encoding the resources necessary to generate and maintain new memory clonotypes with affinity maturation. This cost enforces a minimal homeostatic constraint on the memory repertoire. We neglect any dependence of the cost on the diversification σ, which is secondary and would require adding additional parameters without affecting the qualitative picture. We assume that over evolutionary time scales, the immune system has minimized the average cumulative cost over a large number of infections (Materials and Methods). This optimization yields the optimal parameters of the strategy, namely, the best functions and describing the extent and diversity of affinity maturation and how they should depend on the strength of the infection I. For the sake of simplicity, in Phase Diagram of Optimal Affinity Maturation Strategies, Population Dynamics of Optimized Immune Systems, and Comparison to Experimental Clone Size Distributions, we specialize to the case of constant functions and . We come back to the general case in Inhibition of Affinity Maturation and Antigenic Imprinting.

Phase Diagram of Optimal Affinity Maturation Strategies.

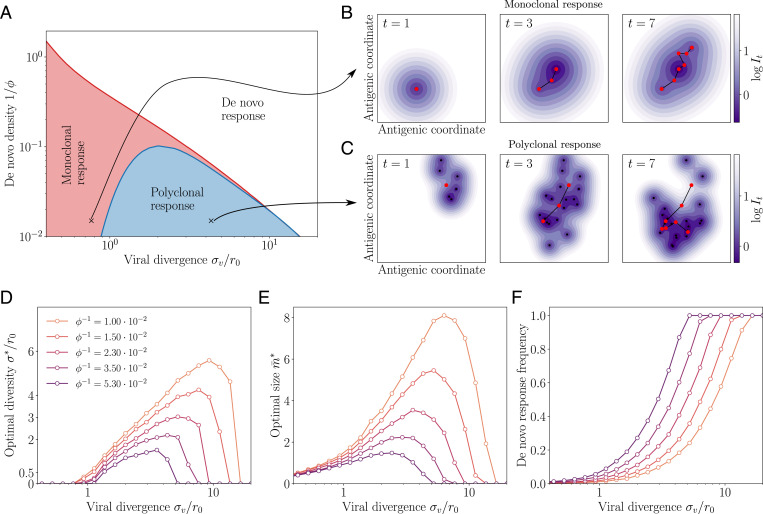

We obtain optimal constant strategies , by minimizing the simulated long-term cost (Eq. 6) in a two-dimensional antigenic space (see Materials and Methods for details of the simulation, optimization procedures, and phase determination). By varying two key parameters, the cost associated to the use of the de novo response, and the virus divergence σv, we see a phase diagram emerge with three distinct phases: the de novo response, monoclonal response, and polyclonal response phases (Fig. 2A). In Fig. 2 B and C, we show examples of the stochastic evolution of memory repertoires with optimal rules in the two phases (monoclonal and polyclonal responses). Fig. 2 D–F show the behavior of the optimal parameters, as well as the fraction of infections for which the de novo response is used (when the maximal infection cost is paid). The general shape and behavior of this phase diagram depends only weakly on the parameter choices (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Regimes of affinity maturation. (A) Phase diagram of the model as a function of the de novo density and viral divergence σv, in a two-dimensional antigenic map. Three phases emerge: monoclonal memory (red), polyclonal memory (blue), and de novo response (white). Snapshots in antigenic space of the sequential immunization by a viral strain in the (B) monoclonal and (C) polyclonal phases. We show the viral position (red dots), memory clonotypes (black dots), and viral trajectory (black line). The color map shows the log infection cost. Parameters σv and correspond to the crosses on the phase diagram in A, with their respective optimal (see arrows). (D) Diversity , (E) optimal size , and (F) frequency of de novo response usage to an immunization challenge for different de novo densities . Parameters values: , α = 1, q = 2, d = 2, , and .

When the de novo response is sufficiently protective (small ) or when the virus mutates too much between infections (large σv), the optimal strategy is to produce no memory cells at all () and rely entirely on the de novo response, always paying a fixed cost (de novo phase).

When the virus divergence σv is small relative to the cross-reactivity range r0, it is beneficial to create memory clonotypes () but with no diversity, (monoclonal response). In this case, all newly created clonotypes are invested into a single antigenic position at that perfectly recognizes the virus. This strategy is optimal because subsequent infections, typically caused by similar viral strains of the virus, are well recognized by these memory clonotypes.

For larger but still moderate virus divergences σv, this perfectly adapted memory is not sufficient to protect from mutated strains: the optimal strategy is rather to generate a polyclonal memory response, with . In this strategy, the immune system hedges its bet against future infections by creating a large diversity of clonotypes that cover the vicinity of the encountered strain. The created memories are thus less efficient against the current infection, which they never will have to deal with. The advantage of this strategy is to anticipate future antigenic mutations of the virus. This diversified pool of cells with moderate affinity is in agreement with recent experimental observations (2, 18, 46, 47). The diversity of the memory pool is supported by a large number of clonotypes (Fig. 2D). As the virus divergence σv is increased, the optimal strategy is to scatter memory cells farther away from the encountered strain (increasing ; Fig. 2E). However, when σv is too large, both drop to zero as the de novo response takes over (Fig. 2F). Increasing the de novo density also favors the de novo phase. When there is no proliferation on average, i.e., , there even exists a threshold above which the de novo response strategy is always best (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Appendix B: Transition from Monoclonal to De Novo Phase at σv = 0 for estimates of that threshold).

We derived analytical results and scaling laws in a simplified version of the model, where cross-reactivity is ideally sharp and where memory cells survive only until the next infection. The results are derived in SI Appendix and illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S2. In this simplified setting, the monoclonal to polycolonal transition occurs at , consistent with the intuition that diversification occurs when the virus is expected to escape out of the cross-reactivity radius. The polyclonal to de novo response transition occurs at , when basal coverage by the naive repertoire and the rest of the immune system outcompetes the protection afforded by memory cells relative to their cost κ.

In summary, the model predicts the two expected regimes of de novo response and memory use depending on the parameters that set the costs of infections and memory formation. However, in addition, it shows a third phase of polyclonal response, where affinity maturation acts as an anticipation mechanism whose role is to generate a large diversity of cells able to respond to future challenges. The prediction of a less focused and thus weaker memory pool observed experimentally is thus rationalized as a result of a bet-hedging strategy.

Population Dynamics of Optimized Immune Systems.

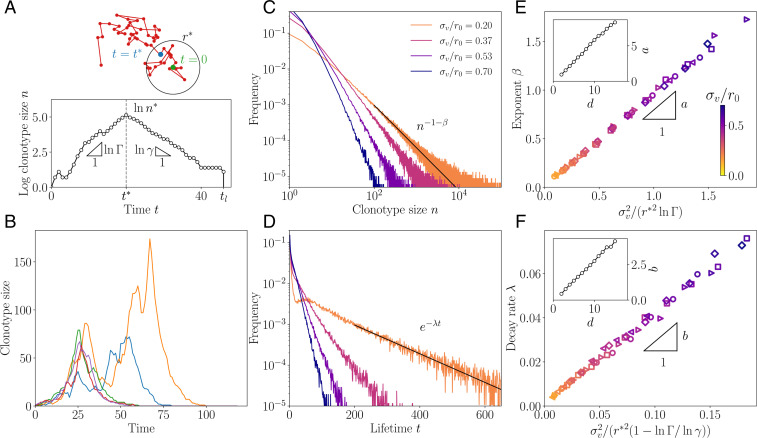

We now turn to the population dynamics of the memory repertoire. When the virus drifts slowly in antigenic space (small σv), the same clonotypes get reactivated multiple times, causing their proliferation, provided that . This reactivation continues until the virus leaves the cross-reactivity range of the original clonotype, at which point the memory clone decays and eventually goes extinct (Fig. 3A). Typical clonotype size trajectories from the model are shown in Fig. 3B. They show large variations in both their maximal size and lifetime. The distribution of clonotype abundances, obtained from a large number of simulations, is indeed very broad, with a power law tail (Fig. 3C). The lifetime of clonotypes, defined as the time from emergence to extinction, is distributed according to an exponential distribution (Fig. 3D). The exponents governing the tails of these distributions, β and γ, depend on the model parameters, in particular the divergence σv.

Fig. 3.

Clonotype dynamics and distribution. (A) Sketch of a recall response generated by sequential immunization with a drifting strain. Clonotypes first grow with multiplicative rate , until they reach the effective cross-reactivity radius , culminating at , after which they decay with rate γ until extinction at time tl. (B) Sample trajectories of clonotypes generated by sequential immunization with a strain of mutability . (C) Distribution of clonotype size for varying virus mutability . (D) Distribution of the lifetime of a clonotype for varying virus mutability . In B–D, the proliferation parameters are set to , i.e., . (E) Scaling relation of the power law exponent for varying values of the parameters. (Inset) Dependence of the proportionality factor a on dimension. (F) Scaling relation of the decay rate λ for varying , with scaling of the proportionality factor b. In both E and F, the different parameters used are , i.e., (diamonds); , i.e., (squares); , i.e., (circles); , i.e., (triangles pointing to the right); and , i.e., (triangles pointing to the left). In B–F, the strategy was optimized for and . The color code for is consistent across C–F. In B–F, the other parameters used are α = 1, q = 2, and d = 2.

We can understand the emergence of these distributions using a simple scaling argument, detailed in SI Appendix. The peak size of a clonotype depends on the number of successive infections by viral strains remaining within a distance from the clonotype, under which it continues expanding. This number has a long exponential tail with characteristic time . One can show that this translates into a power law tail for the distribution of clonotype sizes,

| [3] |

and an exponential tail for the lifetime of clonotypes,

| [4] |

This simple scaling argument predicts the exponents β and λ fairly well: Fig. 3 E and F confirm the validity of the scaling relations Eqs. 3 and 4 against direct evaluation from simulations, for d = 2 and q = 2. These scalings still hold for different parameter choices (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

These scaling relations are valid up to a geometry-dependent prefactor, which is governed by dimensionality and the shape of the cross-reactivity kernel. In SI Appendix, we calculate this prefactor in the special case of an all-or-nothing cross-reactivity function, . Generally, β increases with d, as shown in Fig. 3 E and F, Insets, for q = 2. In higher dimensions, there are more routes to escape the cross-reactivity range and thus a faster decaying tail of large clonotypes. This effect cannot be explained by having more dimensions in which to mutate, since the antigenic variance is distributed across each dimension, according to . Rather, it results from the absence of antigenic back-mutations: in high dimensions, each mutation drifts away from the original strain with a low probability of return, making it easier for the virus to escape and rarer for memory clonotypes to be recalled upon infections by mutant strains.

Comparison to Experimental Clone Size Distributions.

The power law behavior of the clone size distribution predicted from the model (Fig. 3E) can be directly compared to existing data on bulk repertoires. While the model makes a prediction for subsets of the repertoire specific to a particular family of pathogens, the same power law prediction is still valid for the entire repertoire, which is a mixture of such subrepertoires. Power laws have been widely observed in immune repertoires: from early studies of repertoire sequencing data of BCR in zebrafish (5, 48), to the distribution of sizes of clonal families of human immunoglobulin G (IgG) BCR (number of unique sequences in a lineage stemming from a common naive ancestor) (14, 49), as well as in T cell receptor repertoires (6). However, these power laws have not yet been reported in the clonotype abundance distribution of human BCR (number of copies of unique BCR sequences).

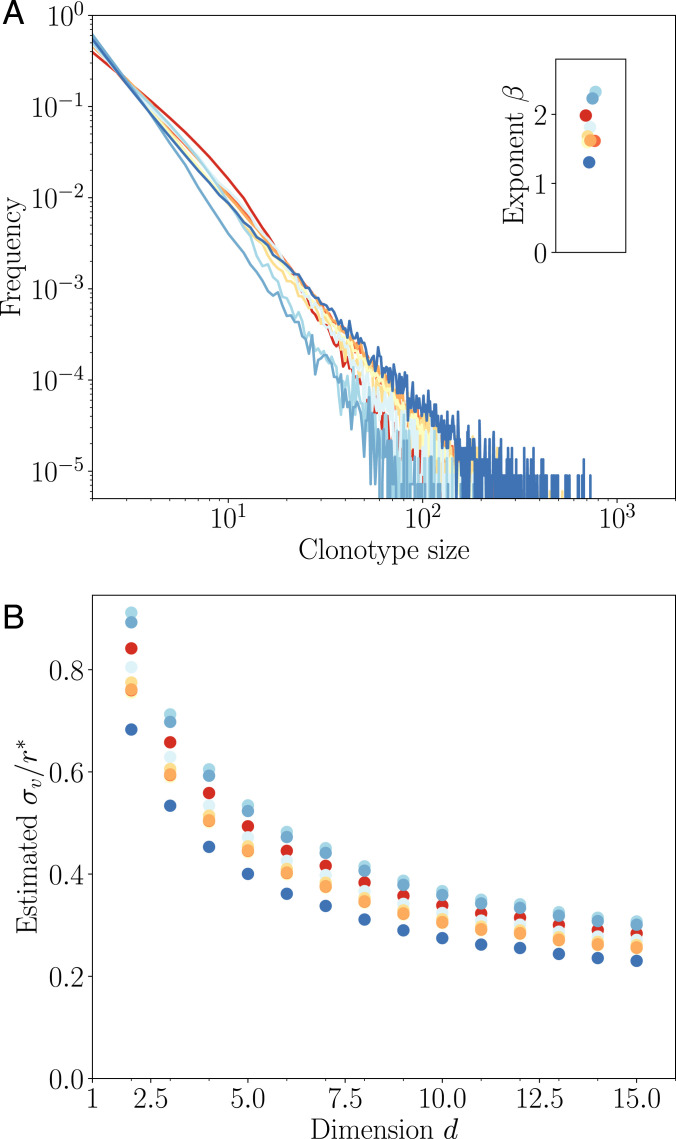

To fill this gap, we used publicly available IgG repertoire data of nine human donors from a recent ultradeep repertoire profiling study of immunoglobulin heavy chains (IGH) (50). The data were downloaded from Sequence Read Archive and processed as in ref. 49. Repertoires were obtained from the sequencing of IGH messenger RNA molecules to which unique molecular identifiers (UMI) were appended. For each IGH nucleotide clonotype found in the dataset, we counted the number of distinct UMI attached to it, as a proxy for the overall abundance of that clonotype in the expressed repertoire. The distributions of these abundances are shown for all nine donors in Fig. 4A. In agreement with the theory, they display a clear power law decay , with to 2.4.

Fig. 4.

Comparison to repertoire data. (A) Clonotype abundance distribution of IgG repertoires of healthy donors from ref. 50. (B) Estimated mutatibility σv in units of the rescaled cross-reactivity , defined as the antigenic distance at which clonotypes stop growing. σv is obtained as a function of d by inverting the linear relationship estimated in Fig. 3E, Inset, assuming q = 2 and (estimated from ref. 18).

Since the experimental distribution is derived from small subsamples of the blood repertoire, the absolute abundances cannot be directly compared to those of the model. In particular, subsampling means that the experimental distribution focuses on the very largest clonotypes. Thus, comparisons between model and data should be restricted to the tail behavior of the distribution, namely, on its power law exponent β. The bulk repertoire is a mixture of antigen-specific subrepertoires, each predicted to be a power law with a potentially different exponent. The resulting distribution is still a power law dominated by the largest exponent.

We used this comparison to predict from the exponent β the virus divergence between infections. To do so, we fit a linear relationship to Fig. 3E, Inset, and invert it for various values of the dimension d to obtain . We fixed , which corresponds to a 40% boost of memory B cells upon secondary infection, inferred from a fourfold boost following four sequential immunizations reported in mice (18). The result is robust to the choice of donor but decreases substantially with dimension because higher dimensions mean faster escape and thus a lower divergence for a given measured exponent (Fig. 4B). The inferred divergence σv is always lower than, but of the same order as, the effective cross-reactivity range , suggesting that the operating point of the immune system falls in the transition region between the monoclonal and polyclonal response phases (Fig. 2A).

Inhibition of Affinity Maturation and Antigenic Imprinting.

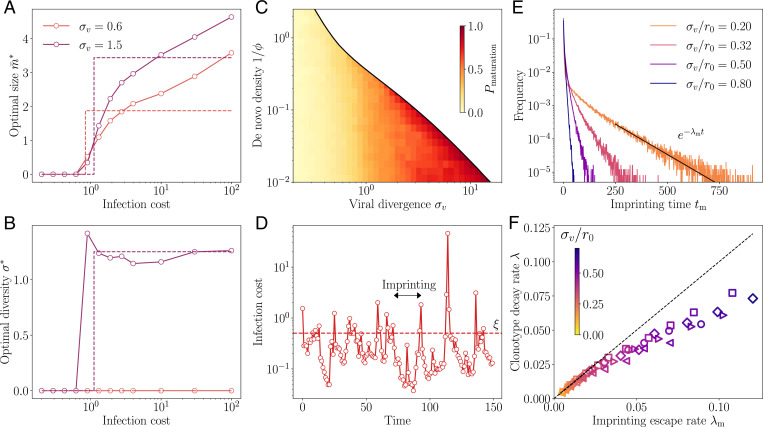

In this section we come back to general strategies where the process of affinity maturation depends on the immune history through the infection cost I experienced by the system during the early immune response, which controls the number and diversity of newly created memories following that response: and . The optimization of the loss function in Eq. 2 is now carried out with respect to two functions of I. To achieve this task, we optimize with respect to discretized functions and taken at n values of the infection cost I between 0 and . From this optimization, a clear transition emerges between a regime of complete inhibition of affinity maturation () at small infection costs and a regime of affinity maturation () at larger infection costs (Fig. 5A). In the phase where affinity maturation occurs, the optimal diversity is roughly constant (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Imprinting and backboosting. Optimal regulatory functions for (A) the number and (B) the diversity of new memories as a function of the infection cost I, for two values for the viral divergence. These functions show a sharp transition from no memory formation to some memory formation, suggesting that they be replaced by simpler step functions (dashed lines). This step function approximation is used in C–F. (C) Frequency of infections leading to affinity maturation in the optimal strategy. The frequency increases with the virus divergence σv, up to the point of the transitions to the de novo phase where memory is not used at all. (D) Typical trajectory of infection cost in sequential infections at . When the cost goes beyond the threshold ξ, affinity maturation is activated, leading to a drop in infection cost. These periods of suboptimal memory describe an original antigenic sin, whereby the immune system is frozen in the state imprinted by the last maturation event. (E) Distribution of imprinting times, i.e., the number of infections between affinity maturation events, decays exponentially with rate λm. The proliferation parameters in A–E are set to and . (F) Predicted scaling of λm with the clonotype decay rate λ from Fig. 3 D and F. In F, the different parameters used are , i.e., (diamonds); , i.e., (squares); , i.e., (circles); , i.e., (triangles pointing to the right); and , i.e., (triangles pointing to the left). The color code for is consistent across E and F. In A–F, the strategy was optimized for and . In D–F, the other parameters used are α = 1, q = 2, and d = 2.

This transition means that when preexisting protection is good enough, the optimal strategy is not to initiate affinity maturation at all, to save the metabolic cost . This inhibition of affinity maturation is called antigenic imprinting and is linked to the notion of original antigenic sin, whereby the history of past infections determines the process of memory formation, usually by suppressing it. This phenomenon leads to the paradoxical prediction that a better experienced immune system is less likely to form efficient memory upon new infections. Importantly, in our model this behavior does not stem from a mechanistic explanation, such as competition for antigen or T cell help between the early memory response and germinal centers, but rather as a long-term optimal strategy maximizing immune coverage while minimizing the costs of repertoire rearrangement.

To simplify the investigation of antigenic imprinting, we approximate the optimal strategies in Fig. 5 A and B by step functions, with a suppressed phase, , for and an active phase, and , for . The threshold ξ is left as an optimization parameter, in addition to σ and . Optimizing with respect to these three parameters, we observe that the frequency of affinity maturation events mostly depends on σv (Fig. 5C). While this threshold remains approximately constant, the frequency of affinity maturation events increases as σv increases. At small σv, the optimal strategy is to extensively backboost existing memory cells; for large σv, the growing unpredictability of the next viral move makes it more likely to have recourse to affinity maturation. In other words, when the virus is stable (low σv), the immune system is more likely to capitalize on existing clonotypes and not implement affinity maturation because savings made on the plasticity cost outweigh the higher infection cost. As the virus drifts away with time, this infection cost also increases, until it reaches the point where affinity maturation becomes worthwhile again.

Trajectories of the infection cost show the typical dynamics induced by backboosting, with long episodes where existing memory remains sufficient to keep the cost below ξ (Fig. 5D), interrupted by infections that fall too far away from existing memory, triggering a new episode of affinity maturation and concomitant drop in the infection cost.

We call the time between affinity maturation events . Its mean is equal to the inverse of the frequency of maturation events and thus decreases with σv. Its distribution, shown Fig. 5E, has an exponential tail with exponent . The exponential tail of the distribution of is dominated by episodes where the viral strain drifted less than expected. In that case, the originally matured clonotype grows to a large size, offering protection for a long time, even after it has stopped growing and only decays. We therefore expect that in the case of a slowly evolving virus , the escape rate from the suppressed phase is given by the clonotype decay rate: . We verify this prediction in Fig. 5F. Interestingly, for slowly evolving viruses, the typical clonotype lifetime diverges, leading to a lifelong imprinting by the primary immune challenge. Conversely, as the viral divergence σv grows, the imprinting time decays faster than the typical clonotype lifetime, and the extent of the imprinting phenomenon is limited.

Discussion

Adaptive immunity coordinates multiple components and cell types across entire organisms over many space and time scales. Because it is difficult to empirically characterize the immune system at the system scale, normative theories have been useful to generate hypotheses and fill the gap between observations at the molecular, cellular, and organismal scales (51, 52). Such approaches include clonal selection theory (53), or early arguments about the optimal size and organization of immune repertoires (40, 54, 55) and of affinity maturation (20, 21). While these theories do not rely on describing particular mechanisms of immune function, they may still offer quantitative insights and help predict new mechanisms or global rules of operation.

Previous work developed models of repertoire organization as a constrained optimization problem where the expected future harm of infection, or an ad hoc utility function, is minimized (30, 42, 43, 56). In ref. 43, it was assumed clonotypes specific to all antigens are present at all times in the repertoire; the mechanism of immune memory then merely consists of expanding specific clonotypes at the expense of others. This assumption describes T cell repertoires well, where there are naive cells with good affinity to essentially any antigen (57). For B cells the situation is more complex because of affinity maturation. In addition, reorganizing the repertoire through mutation and selection has a cost and is subject to metabolic and physical constraints.

Our work addresses these challenges by proposing a framework of discrete time decision process to describe the optimal remodeling of the B cell repertoire following immunization, through a combination of affinity maturation and backboosting. While similar to ref. 30, our approach retains the minimal amount of mechanistic details and focuses on questions of repertoire remodeling, dynamics, and structure. The specific choices of the cost functions were driven by simplicity, while still retaining the ability to display emergent behavior. Generalizing the metabolic cost function to include, e.g., costs of diversification (through a dependence on σ) or of cell proliferation is not expected to affect our results qualitatively, although it may shift the exact positions of the transition boundaries.

We investigated strategies that maximize long-term protection against subsequent challenges and minimize short-term resource costs due to the affinity maturation processes. Using this model, we observed that optimal strategies may be organized into three main phases as the pathogen divergence and de novo coverage are varied. We expect these distinct phases to coexist in the same immune system as there exists a wide range of pathogen divergences, depending on their evolutionary speed and typical frequency of recurrence.

For fast recurring or slowly evolving pathogens, the monoclonal response ensures a very specific and targeted memory. This role could be played by long-lived plasma cells. These cells are selected through the last rounds of affinity maturation, meaning that they are very specific to the infecting strain (58). Yet, despite not being called memory cells, they survive for long times in the bone marrow, providing long-term immunity.

For slow recurring or fast evolving pathogens, the polyclonal response provides a diverse memory to preempt possible antigenic drift of the pathogen. The function could be fulfilled by memory B cells, which are released earlier in the affinity maturation process, implying that they are less specific to the infecting strain, but collectively can cover more immune escape mutations. While affinity maturation may start from both memory and naive B cells during sequential challenges, the relative importance of each is still debated (59–61). Our model does not commit on this question since we assume that the main benefit of memory is on the infection cost, rather than its reuse in subsequent rounds of affinity maturation.

For simplicity our model assumed random evolution of the virus. However, there is evidence, backed by theoretical arguments, that successive viral strains move in a predominant direction in antigenic space, as a result of immune pressure by the host population (29, 62, 63). While it is unlikely that the immune system has evolved to learn how to exploit this persistence of antigenic motion in a specific manner, such a bias in the random walk is expected to affect the optimal strategy, as we checked in simulations (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The bias of the motion effectively increases the effective divergence of the virus, favoring the need for more numerous and more diverse memory cells. However, it does not seem to affect the location of the polyclonal to de novo response transition.

The model is focused on acute infections, motivated by the assumption that recurring infections and antigenic drift are the main drivers of affinity maturation evolution. However, much of the model and its results can be reinterpreted for chronic infections. In that context, the sequential challenges of our model would correspond to selective sweeps in the viral population giving rise to new dominant variants. While the separation of time scales between the immune response and the rate of reinfections would no longer hold, we expect some predictions, such as the distribution of clonotype sizes and the emergence of imprinting, to hold true. Chronic infections also imply that the virus evolves as a function of how the immune system responds. Including this feedback would require a game-theoretic treatment. We speculate that it would drive antigenic motion in a persistent direction, as argued earlier and evaluated in SI Appendix, Fig. S4.

We investigated strategies where the outcome of affinity maturation is impacted by the efficiency of the early immune response. It is known that the extrafollicular response can drastically limit antigen availability and T cell help, decreasing the extent of affinity maturation and the production of new plasma and memory cells (64). Our general framework allows for but does not presume the existence of such negative feedbacks. Instead, they naturally emerge from our optimization principle. We further predict a sharp transition from no affinity maturation to some affinity maturation as a function of the infection cost. This prediction can be interpreted as the phenomenon of antigenic imprinting widely described in sequential immunization assays (35), or original antigenic sin (34). It implies that having been exposed to previous strains of the virus is detrimental to mounting the best possible immune response. Importantly, while antigenic imprinting has been widely described in the literature, no evolutionary justification was ever provided for its existence. Our model explains it as a long-term optimal strategy for the immune system, maximizing immune coverage while minimizing repertoire rearrangements (encoded in the cost κm).

We believe this framework can be generalized to investigate interactions between slow and fast varying epitopes, which are known to be at the core of the low effectiveness of influenza vaccines (32). When during sequential challenges only one of multiple epitopes changes at a time, it may be optimal for the immune system to rely on its protections against the invariant epitopes. Only after all epitopes have escaped immunity does affinity maturation get reactivated concomitantly to a spike of infection harm, similar to our result for a single antigen.

Our model can explain previously reported power laws in the distributions of abundances of BCR clonotypes. However, there exist alternative explanations to such power laws (65, 66) that do not require antigenically drifting antigens. Our model predictions could be further tested in a mouse model, by measuring the B cell recall response to successive challenges (35), but with epitopes carefully designed to drift in a controlled manner, to check the transition predicted in Fig. 5A. While not directly included in our model, our results also suggest that the size of the inoculum, which would affect the infection cost, should also affect backboosting. This effect could also be tested in mouse experiments. The predicted relationships between viral divergence and the exponents of the power law and clonotype lifetimes (Fig. 3 E and F) could be tested in longitudinal human samples, by sequencing subrepertoires specific to pathogens with different rates of antigenic evolution. This would require computational prediction of what BCRs are specific to what pathogen, which in general is difficult.

We only considered a single pathogenic species at a time, with the assumption that pathogens are antigenically independent, so that the costs relative to different pathogens are additive. Possible generalizations could include secondary infections, as well as antigenically related pathogens showing patterns of cross-immunity (such as cowpox and smallpox or different groups of influenza), which could help us shed light on complex immune interactions between diseases and serotypes, such as negative interference between different serotypes of the Dengue fever leading to hemorrhagic fever or of the human Bocavirus affecting different body sites (34).

Materials and Methods

Mathematical Model.

The viral strain is modeled by its antigenic position, which follows a discrete random walk:

| [5] |

where ηt is a normally distributed d-dimensional variable with and .

The positions of newly created memory receptors are drawn at random according to , where ξj is normally distributed with and . Their initial sizes are set to .

Upon further stimulation, the new size of a preexisting clonotype right after proliferation is given by , where is the cross-reactivity kernel. After proliferation, each memory may die with probability γ, so that the final clonotype size after an infection cycle is given by .

The objective to be minimized is formally defined as a long-term average:

| [6] |

The optimal strategy is defined as

| [7] |

where and are, in the general case, full functions of the infection cost I, and . In all results except in Inhibition of Affinity Maturation and Antigenic Imprinting, we use the Ansatz of constant functions, . In Inhibition of Affinity Maturation and Antigenic Imprinting, we first perform optimization over discretized functions , defined over n chosen values of . Then, we parametrize the functions as step functions, and m(I) = 0 for and and m(I) = m for , and optimize over the three parameters .

Monte Carlo Estimation of the Optimal Strategies.

The average cumulative cost in Eq. 6 is approximated by a Monte Carlo method. To ensure the simulated repertoire reaches stationarity, we start from a naive repertoire and discard an arbitrary number of initial viral encounters. Because the process is ergodic, simulating a viral-immune trajectory over a long time horizon is equivalent to simulating M independent trajectories of smaller length T. To ensure the independence of our random realizations across our M parallel streams we use the random number generators method split provided in Tina’s Random Number Generator library (67). The cumulative cost function is convex for the range of parameters tested. To optimize under positivity constraints for the objective variables σ, , and ξ, we use Py-BOBYQA (68), a coordinate descent algorithm supporting noisy objective functions.

The polyclonal to monoclonal (red curve) and memory to de novo response (blue curve) boundaries of the phase diagrams in SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3, are obtained by solving in the monoclonal phase and in the de novo phase. Both these derivatives can be approximated by finite differences with arbitrary tolerances on σ and . We fix the tolerance on σ to 0.2 and the tolerance on to 0.01. To obtain the root of these difference functions, we use a bisection algorithm. In order to further decrease the noise level, we compute the difference functions across pairs of simulations, each pair using an independent sequence of pathogens of length L = 400. The number of independent pairs of simulations used for each value of σv and is .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the European Research Council Consolidator grant COG 724208, Agence Nationale de la Recherche grant ANR-19-CE45-0018 “RESP-REP,” and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) grant CRC 1310 “Predictability in Evolution.” We thank Natanael Spisak for preprocessing the raw data from ref. 50 and for useful discussions and suggestions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. A.P. is a Guest Editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2113512119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The data and codes used to generate the figures are available in GitHub (https://github.com/statbiophys/seqam). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Nieuwenhuis P., Opstelten D., Functional anatomy of germinal centers. Am. J. Anat. 170, 421–435 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victora G. D., Nussenzweig M. C., Germinal centers. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 429–457 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisen H. N., Siskind G. W., Variations in affinities of antibodies during the immune response. Biochemistry 3, 996–1008 (1964). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisel F., Shlomchik M., Memory B cells of mice and humans. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 35, 255–284 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein J. A., Jiang N., R. A. White, 3rd, Fisher D. S., Quake S. R., High-throughput sequencing of the zebrafish antibody repertoire. Science 324, 807–810 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mora T., Walczak A. M., Quantifying Lymphocyte Receptor Diversity in Systems Immunology (CRC Press, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kocks C., Rajewsky K., Stepwise intraclonal maturation of antibody affinity through somatic hypermutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 8206–8210 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinstein S. H., Louzoun Y., Shlomchik M. J., Estimating hypermutation rates from clonal tree data. J. Immunol. 171, 4639–4649 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kepler T. B., Reconstructing a B-cell clonal lineage. I. Statistical inference of unobserved ancestors. F1000 Res. 2, 103 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yaari G., Kleinstein S. H., Practical guidelines for B-cell receptor repertoire sequencing analysis. Genome Med. 7, 121 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ralph D. K., F. A. Matsen, 4th, Likelihood-based inference of B cell clonal families. PLOS Comput. Biol. 12, e1005086 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao H. X., et al.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature 496, 469–476 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nourmohammad A., Otwinowski J., Łuksza M., Mora T., Walczak A. M., Fierce selection and interference in B-cell repertoire response to Chronic HIV-1. Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 2184–2194 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang N., et al., Lineage structure of the human antibody repertoire in response to influenza vaccination. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 171ra19 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horns F., Vollmers C., Dekker C. L., Quake S. R., Signatures of selection in the human antibody repertoire: Selective sweeps, competing subclones, and neutral drift. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 1261–1266 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith K. G. C., Light A., Nossal G. J. V., Tarlinton D. M., The extent of affinity maturation differs between the memory and antibody-forming cell compartments in the primary immune response. EMBO J. 16, 2996–3006 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisel F. J., Zuccarino-Catania G. V., Chikina M., Shlomchik M. J., A temporal switch in the germinal center determines differential output of memory B and plasma cells. Immunity 44, 116–130 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viant C., et al., Antibody affinity shapes the choice between memory and germinal center B cell fates. Cell 183, 1298–1311.e11 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oprea M., Perelson A. S., Somatic mutation leads to efficient affinity maturation when centrocytes recycle back to centroblasts. J. Immunol. 158, 5155–5162 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oprea M., van Nimwegen E., Perelson A. S., Dynamics of one-pass germinal center models: Implications for affinity maturation. Bull. Math. Biol. 62, 121–153 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kepler T. B., Perelson A. S., Somatic hypermutation in B cells: An optimal control treatment. J. Theor. Biol. 164, 37–64 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S., et al., Manipulating the selection forces during affinity maturation to generate cross-reactive HIV antibodies. Cell 160, 785–797 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sachdeva V., Husain K., Sheng J., Wang S., Murugan A., Tuning environmental timescales to evolve and maintain generalists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 12693–12699 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molari M., Eyer K., Baudry J., Cocco S., Monasson R., Quantitative modeling of the effect of antigen dosage on B-cell affinity distributions in maturating germinal centers. eLife 9, e55678 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grenfell B. T., et al., Unifying the epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of pathogens. Science 303, 327–332 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanquart F., Gandon S., Time-shift experiments and patterns of adaptation across time and space. Ecol. Lett. 16, 31–38 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cobey S., Wilson P., F. A. Matsen, 4th, The evolution within us. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20140235 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koelle K., Cobey S., Grenfell B., Pascual M., Epochal evolution shapes the phylodynamics of interpandemic influenza A (H3N2) in humans. Science 314, 1898–1903 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchi J., Lässig M., Walczak A. M., Mora T., Antigenic waves of virus-immune coevolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2103398118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnaack O. H., Nourmohammad A., Optimal evolutionary decision-making to store immune memory. eLife 10, e61346 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Francis T., On the doctrine of original antigenic sin. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 104, 572–578 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cobey S., Hensley S. E., Immune history and influenza virus susceptibility. Curr. Opin. Virol. 22, 105–111 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoskins T. W., Davies J. R., Smith A. J., Miller C. L., Allchin A., Assessment of inactivated influenza-A vaccine after three outbreaks of influenza A at Christ’s Hospital. Lancet 1, 33–35 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vatti A., et al., Original antigenic sin: A comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 83, 12–21 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J. H., Skountzou I., Compans R., Jacob J., Original antigenic sin responses to influenza viruses. J. Immunol. 183, 3294–3301 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith D. J., Forrest S., Ackley D. H., Perelson A. S., Variable efficacy of repeated annual influenza vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14001–14006 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linderman S. L., Hensley S. E., Antibodies with ‘original antigenic sin’ properties are valuable components of secondary immune responses to influenza viruses. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005806 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yewdell J. W., Santos J. J. S., Original antigenic sin: How original? How sinful? Cold Spring Harb . Perspect. Med. 11, 038786 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worobey M., Plotkin S., Hensley S. E., Influenza vaccines delivered in early childhood could turn antigenic sin into antigenic blessings. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 10, 038471 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perelson A. S., Oster G. F., Theoretical studies of clonal selection: Minimal antibody repertoire size and reliability of self-non-self discrimination. J. Theor. Biol. 81, 645–670 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen C., et al.; PHIRST group, Asymptomatic transmission and high community burden of seasonal influenza in an urban and a rural community in South Africa, 2017-18 (PHIRST): A population cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health 9, e863–e874 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayer A., Balasubramanian V., Mora T., Walczak A. M., How a well-adapted immune system is organized. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 5950–5955 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayer A., Balasubramanian V., Walczak A. M., Mora T., How a well-adapting immune system remembers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 8815–8823 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oidtman R. J., et al., Influenza immune escape under heterogeneous host immune histories. Trends Microbiol. 29, 1072–1082 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakagawa R., et al., Permissive selection followed by affinity-based proliferation of GC light zone B cells dictates cell fate and ensures clonal breadth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2016425118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tas J. M. J., et al., Visualizing antibody affinity maturation in germinal centers. Science 351, 1048–1054 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuraoka M., et al., Complex antigens drive permissive clonal selection in germinal centers. Immunity 44, 542–552 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mora T., Walczak A. M., Bialek W., C. G. Callan, Jr., Maximum entropy models for antibody diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5405–5410 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spisak N., Walczak A. M., Mora T., Learning the heterogeneous hypermutation landscape of immunoglobulins from high-throughput repertoire data. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 10702–10712 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Briney B., Inderbitzin A., Joyce C., Burton D. R., Commonality despite exceptional diversity in the baseline human antibody repertoire. Nature 566, 393–397 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chakraborty A. K., A perspective on the role of computational models in immunology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 35, 403–439 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Altan-Bonnet G., Mora T., Walczak A. M., Quantitative immunology for physicists. Phys. Rep. 849, 1–83 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burnet F. M., A modification of Jerne’s theory of antibody production using the concept of clonal selection. Aust. J. Sci. 20, 67–69 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perelson A. S., Mirmirani M., Oster G. F., Optimal strategies in immunology. I. B-cell differentiation and proliferation. J. Math. Biol. 3, 325–367 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perelson A. S., Mirmirani M., Oster G. F., Optimal strategies in immunology. II. B memory cell production. J. Math. Biol. 5, 213–256 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.R. Marsland, 3rd, Howell O., Mayer A., Mehta P., Tregs self-organize into a computing ecosystem and implement a sophisticated optimization algorithm for mediating immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2011709118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moon J. J., et al., Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity 27, 203–213 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Akkaya M., Kwak K., Pierce S. K., B cell memory: Building two walls of protection against pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 229–238 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turner J. S., et al., Human germinal centres engage memory and naive B cells after influenza vaccination. Nature 586, 127–132 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mesin L., et al., Restricted clonality and limited germinal center reentry characterize memory B cell reactivation by boosting. Cell 180, 92–106.e11 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong R., et al., Affinity-restricted memory B cells dominate recall responses to heterologous flaviviruses. Immunity 53, 1078–1094.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bedford T., Rambaut A., Pascual M., Canalization of the evolutionary trajectory of the human influenza virus. BMC Biol. 10, 38 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bedford T., et al., Integrating influenza antigenic dynamics with molecular evolution. eLife 3, e01914 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arulraj T., Binder S. C., Robert P. A., Meyer-Hermann M., Germinal centre shutdown. Front. Immunol. 12, 2730 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Desponds J., Mora T., Walczak A. M., Fluctuating fitness shapes the clone-size distribution of immune repertoires. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 274–279 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gaimann M. U., Nguyen M., Desponds J., Mayer A., Early life imprints the hierarchy of T cell clone sizes. eLife 9, e61639 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bauke H., Mertens S., Random numbers for large-scale distributed Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 75, 066701 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cartis C., Fiala J., Marteau B., Roberts L., Improving the flexibility and robustness of model-based derivative-free optimization solvers. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 45, 32:1–32:41 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and codes used to generate the figures are available in GitHub (https://github.com/statbiophys/seqam). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.