Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI)–synthesized text, audio, image, and video are being weaponized for the purposes of nonconsensual intimate imagery, financial fraud, and disinformation campaigns. Our evaluation of the photorealism of AI-synthesized faces indicates that synthesis engines have passed through the uncanny valley and are capable of creating faces that are indistinguishable—and more trustworthy—than real faces.

Keywords: deep fakes, face perception

Artificial intelligence (AI)–powered audio, image, and video synthesis—so-called deep fakes—has democratized access to previously exclusive Hollywood-grade, special effects technology. From synthesizing speech in anyone’s voice (1) to synthesizing an image of a fictional person (2) and swapping one person’s identity with another or altering what they are saying in a video (3), AI-synthesized content holds the power to entertain but also deceive.

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) are popular mechanisms for synthesizing content. A GAN pits two neural networks—a generator and discriminator—against each other. To synthesize an image of a fictional person, the generator starts with a random array of pixels and iteratively learns to synthesize a realistic face. On each iteration, the discriminator learns to distinguish the synthesized face from a corpus of real faces; if the synthesized face is distinguishable from the real faces, then the discriminator penalizes the generator. Over multiple iterations, the generator learns to synthesize increasingly more realistic faces until the discriminator is unable to distinguish it from real faces (see Fig. 1 for example real and synthetic faces).

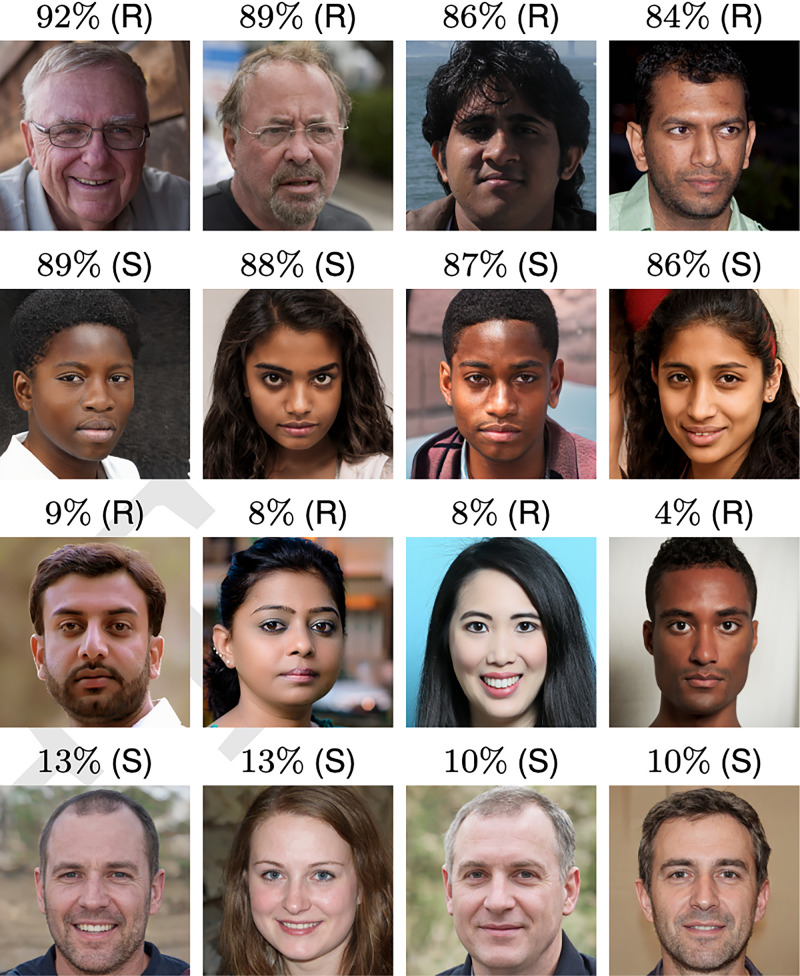

Fig. 1.

The most (Top and Upper Middle) and least (Bottom and Lower Middle) accurately classified real (R) and synthetic (S) faces.

Much has been written in the popular press about the potential threats of deep fakes, including the creation of nonconsensual intimate imagery (more commonly referred to by the misnomer “revenge porn”), small- to large-scale fraud, and adding jet fuel to already dangerous disinformation campaigns. Perhaps most pernicious is the consequence that, in a digital world in which any image or video can be faked, the authenticity of any inconvenient or unwelcome recording can be called into question.

Although progress has been made in developing automatic techniques to detect deep-fake content (e.g., refs. 4–6), current techniques are not efficient or accurate enough to contend with the torrent of daily uploads (7). The average consumer of online content, therefore, must contend with sorting out the real from the fake. We performed a series of perceptual studies to determine whether human participants can distinguish state-of-the-art GAN-synthesized faces from real faces and what level of trust the faces evoked.

Results

Experiment 1.

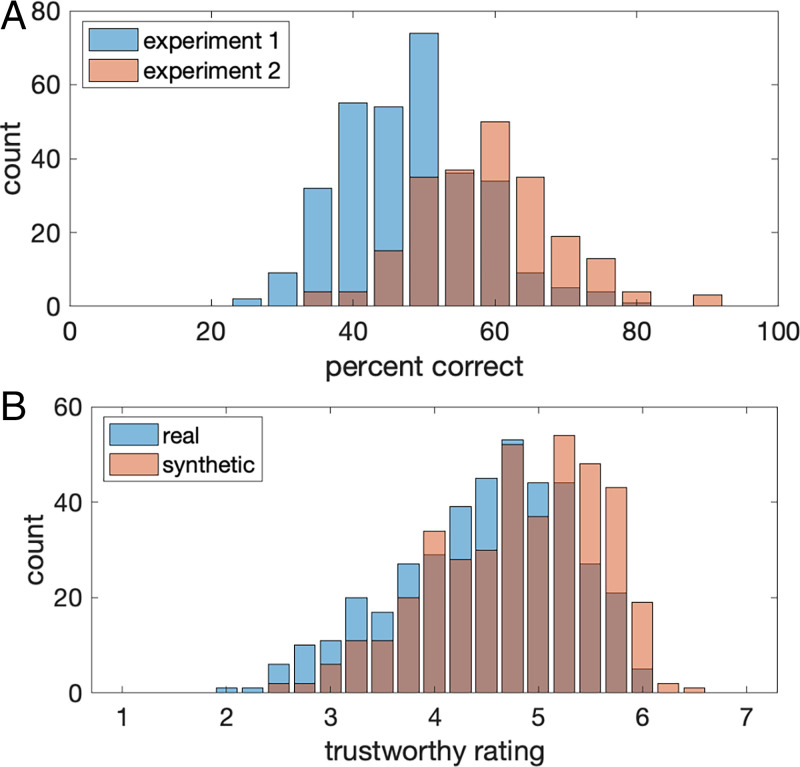

In this study, 315 participants classified, one at a time, 128 of the 800 faces as real or synthesized. Shown in Fig. 2A is the distribution of participant accuracy (blue bars). The average accuracy is 48.2% (95% CI [47.1%, 49.2%]), close to chance performance of 50%, with no response bias: ; . Two repeated-measures binary logistic regression analyses were conducted—one for real and one for synthetic faces—to examine the effect of stimuli gender and race on accuracy. For real faces, there was a significant gender × race interaction, . Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected comparisons revealed that mean accuracy was higher for male East Asian faces than female East Asian faces and higher for male White faces than female White faces. For synthetic faces, there was also a significant gender × race interaction, . For both male and female synthetic faces, White faces were the least accurately classified, and male White faces were less accurately classified than female White faces. We hypothesize that White faces are more difficult to classify because they are overrepresented in the StyleGAN2 training dataset and are therefore more realistic.

Fig. 2.

The distribution of participant accuracy for (A) experiment 1 and experiment 2 (chance performance is 50%), and (B) trustworthy ratings for experiment 3 (a rating of 1 corresponds to the lowest trust).

Experiment 2.

In this study, 219 new participants, with training and trial-by-trial feedback, classified 128 faces taken from the same 800 set of faces as in experiment 1. Shown in Fig. 2A is the distribution of participant accuracy (orange bars). The average accuracy improved slightly to 59.0% (95% CI [57.7%, 60.4%]), with no response bias: ; . Despite providing trial-by-trial feedback, there was no improvement in accuracy over time, with an average accuracy of 59.3% (95% CI [57.8%, 60.7%]) for the first set of 64 faces and 58.8% (95% CI [57.4%, 60.3%]) for the second set of 64 faces. Further analyses to examine the effect of gender and race on accuracy replicated the primary findings of experiment 1. This analysis again revealed that, for both male and female synthetic faces, White faces were the most difficult to classify.

When made aware of rendering artifacts and given feedback, there was a reliable improvement in accuracy; however, overall performance remained only slightly above chance. The lack of improvement over time suggests that the impact of feedback is limited, presumably because some synthetic faces simply do not contain perceptually detectable artifacts.

Experiment 3.

Faces provide a rich source of information, with exposure of just milliseconds sufficient to make implicit inferences about individual traits such as trustworthiness (8). We wondered whether synthetic faces activate the same judgements of trustworthiness. If not, then a perception of trustworthiness could help distinguish real from synthetic faces.

In this study, 223 participants rated the trustworthiness of 128 faces taken from the same set of 800 faces on a scale of 1 (very untrustworthy) to 7 (very trustworthy) (9). Shown in Fig. 2B is the distribution of average ratings (by averaging the ordinal ratings, we are assuming a linear rating scale). The average rating for real faces (blue bars) of 4.48 is less than the rating of 4.82 for synthetic faces (orange bars). Although only 7.7% more trustworthy, this difference is significant []. Although a small effect, Black faces were rated more trustworthy than South Asian faces, but, otherwise, there was no effect across race. Women were rated as significantly more trustworthy than men, 4.94 as compared to 4.36 [].

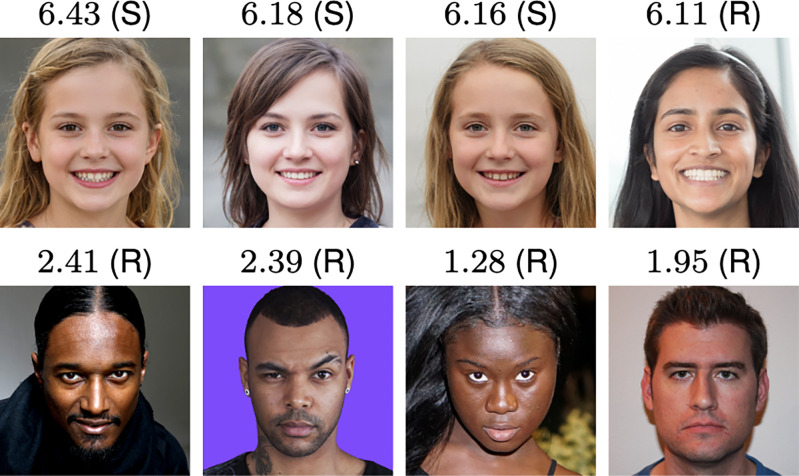

Shown in Fig. 3 are the four most (Fig. 3, Top) and four least (Fig. 3, Bottom) trustworthy faces. The top three most trustworthy faces are synthetic (S), while the bottom four least trustworthy faces are real (R). A smiling face is more likely to be rated as trustworthy, but 65.5% of our real faces and 58.8% of synthetic faces are smiling, so facial expression alone cannot explain why synthetic faces are rated as more trustworthy.

Fig. 3.

The four most (Top) and four least (Bottom) trustworthy faces and their trustworthy rating on a scale of 1 (very untrustworthy) to 7 (very trustworthy). Synthetic faces (S) are, on average, more trustworthy than real faces (R).

Discussion

Synthetically generated faces are not just highly photorealistic, they are nearly indistinguishable from real faces and are judged more trustworthy. This hyperphotorealism is consistent with recent findings (10, 11). These two studies did not contain the same diversity of race and gender as ours, nor did they match the real and synthetic faces as we did to minimize the chance of inadvertent cues. While it is less surprising that White male faces are highly realistic—because these faces dominate the neural network training—we find that the realism of synthetic faces extends across race and gender. Perhaps most interestingly, we find that synthetically generated faces are more trustworthy than real faces. This may be because synthesized faces tend to look more like average faces which themselves are deemed more trustworthy (12). Regardless of the underlying reason, synthetically generated faces have emerged on the other side of the uncanny valley. This should be considered a success for the fields of computer graphics and vision. At the same time, easy access (https://thispersondoesnotexist.com) to such high-quality fake imagery has led and will continue to lead to various problems, including more convincing online fake profiles and—as synthetic audio and video generation continues to improve—problems of nonconsensual intimate imagery (13), fraud, and disinformation campaigns, with serious implications for individuals, societies, and democracies.

We, therefore, encourage those developing these technologies to consider whether the associated risks are greater than their benefits. If so, then we discourage the development of technology simply because it is possible. If not, then we encourage the parallel development of reasonable safeguards to help mitigate the inevitable harms from the resulting synthetic media. Safeguards could include, for example, incorporating robust watermarks into the image and video synthesis networks that would provide a downstream mechanism for reliable identification (14). Because it is the democratization of access to this powerful technology that poses the most significant threat, we also encourage reconsideration of the often laissez-faire approach to the public and unrestricted releasing of code for anyone to incorporate into any application.

At this pivotal moment, and as other scientific and engineering fields have done, we encourage the graphics and vision community to develop guidelines for the creation and distribution of synthetic media technologies that incorporate ethical guidelines for researchers, publishers, and media distributors.

Materials and Methods

Synthetic Faces.

We selected 400 faces synthesized using the state-of-the-art StyleGAN2 (2), ensuring diversity across gender (200 women; 200 men), estimated age (ensuring a range of ages from children to older adults), and race (100 African American or Black, 100 Caucasian, 100 East Asian, and 100 South Asian). To reduce extraneous cues, we only included images with a mostly uniform background, and devoid of any obvious rendering artifacts. This culling of obvious artifacts makes the perceptual task harder. Because the synthesis process is so easy, however, it is reasonable to assume that any intentionally deceptive use of a synthetic face will not contain obvious visual artifacts.

Real Faces.

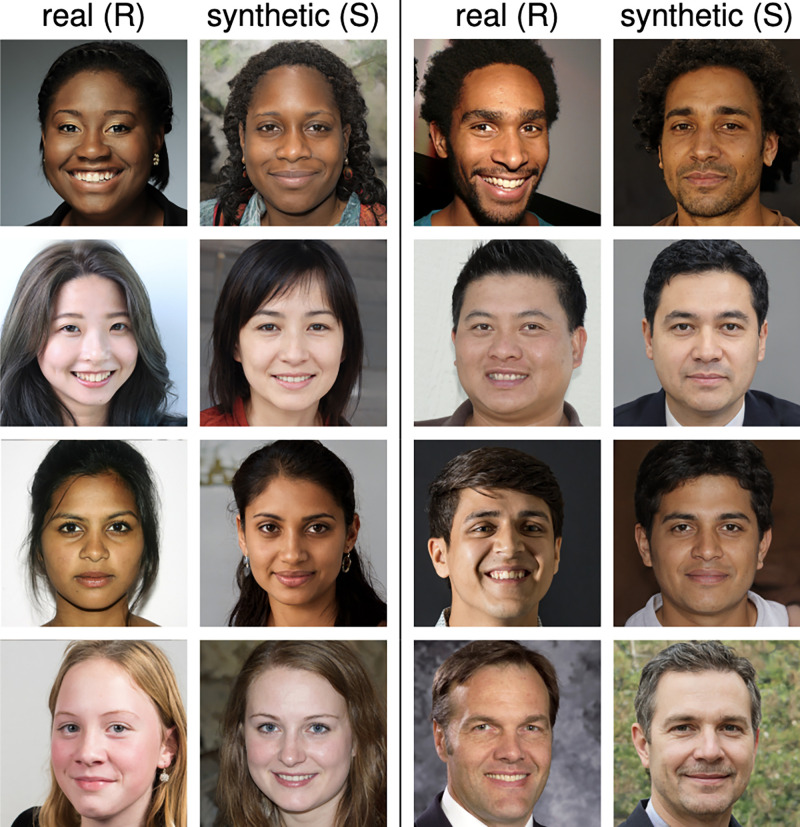

For each synthesized face, we collected a matching real face (in terms of gender, age, race, and overall appearance) from the underlying face database used in the StyleGAN2 learning stage. A standard convolutional neural network descriptor (15) was used to extract a low-dimensional, perceptually meaningful (16) representation of each synthetic face. The extracted representation for each synthetic face—a 4,096-D real-valued vector —was compared with all other facial representations in the data set of 70,000 real faces to find the most similar face. The real face with representation with minimal Euclidean distance to , and satisfying our qualitative selection criteria, is selected as the matching face. As with the synthetic faces, to reduce extraneous cues, we only included images 1) with a mostly uniform background, 2) with unobstructed faces (e.g., no hats or hands in front of face), 3) in focus and high resolution, and 4) with no obvious writing or logos on clothing. We visually inspected up to 50 of the best matched faces and selected the one that met the above criteria and was also matched in terms of overall face position, posture, and expression, and presence of glasses and jewelry. Shown in Fig. 4 are representative examples of these matched real and synthetic faces.

Fig. 4.

A representative set of matched real and synthetic faces.

Perceptual Ratings.

For experiment 1 (baseline), we recruited 315 participants from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk Master Workers. Each participant first read a brief introduction explaining the purpose of the study and a brief explanation of what a synthetic face is. Before beginning, each participant was informed they would be paid $5 for their time, and an extra $5 if their overall accuracy was in the top 20% of response accuracies. Participants were also informed they would see 10 catch trials of obviously synthetic faces with glaring rendering errors. A failure to respond correctly to at least nine of these trials led to the participants not being paid and their data being excluded from our study. Each participant then saw 128 images, one at a time, and specified whether the image was real or synthetic. Participants had an unlimited amount of time to respond and were not provided with feedback after each response.

For experiment 2 (training and feedback), we recruited another 219 Mechanical Turk Master Workers (we had fewer participants in this study because we excluded any participants who completed the first study). Each participant first read a brief introduction explaining the purpose of the study and a brief explanation of what a synthetic face is. Participants were then shown a short tutorial describing examples of specific rendering artifacts that can be used to identify synthetic faces. All other experimental conditions were the same as in experiment 1, except that participants received feedback after each response.

For experiment 3 (trustworthiness), we recruited 223 Mechanical Turk Master Workers. Each participant first read a brief introduction explaining that the purpose of the study was to assess the trustworthiness of a face on a scale of 1 (very untrustworthy) to 7 (very trustworthy). Because there was no correct answer here, no trial-by-trial feedback was provided. Participants were also informed they would see 10 catch trials of faces in which the numeric trustworthy rating was directly overlaid atop the face. A failure to correctly report the specified rating on at least nine of these trials led to the participants not being paid and their data being excluded from our study. Each participant then saw 128 images, one at a time, and was asked to rate the trustworthiness. Participants had an unlimited amount of time to respond.

All experiments were carried out with the approval of the University of California, Berkeley’s Office for Protection of Human Subjects (Protocol ID 2019-07-12422) and Lancaster University’s Faculty of Science and Technology Research Ethics Committee (Protocol ID FST20076). Participants gave fully informed consent prior to taking part in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erik Härkönen, Jaakko Lehtinen, and David Luebke for their masterful synthesis of faces.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data Availability

Images have been deposited in GitHub (https://github.com/NVlabs/stylegan2 and https://github.com/NVlabs/ffhq-dataset). Anonymized experimental stimuli and data have been deposited in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ru36d/).

References

- 1.Oord A., et al., WaveNet: A generative model for raw audio. arXiv [Preprint] (2016). https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.03499 (Accessed 17 January 2022).

- 2.Karras T., et al., “Analyzing and improving the image quality of StyleGAN” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2020), pp. 8110–8119. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suwajanakorn S., Seitz S. M., Kemelmacher-Shlizerman I., Synthesizing Obama: Learning lip sync from audio. ACM Trans. Graph. 36, 95 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L., et al., Face X-ray for more general face forgery detection. arXiv [Preprint] (2019). https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.13458 (Accessed 17 January 2022).

- 5.Agarwal S., et al., “Protecting world leaders against deep fakes” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2019), pp. 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S. Y., Wang O., Zhang R., Owens A., Efros A. A., “CNN-generated images are surprisingly easy to spot… for now” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2020), pp. 8695–8704. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farid H., Commentary: Digital forensics in a post-truth age. Forensic Sci. Int. 289, 268–269 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis J., Todorov A., First impressions: Making up your mind after a 100-ms exposure to a face. Psychol. Sci. 17, 592–598 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stolier R. M., Hehman E., Keller M. D., Walker M., Freeman J. B., The conceptual structure of face impressions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9210–9215 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lago F., et al., More real than real: A study on human visual perception of synthetic faces. arXiv [Preprint] (2021). https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.07226 (Accessed 17 January 2022).

- 11.Hulzebosch N., Ibrahimi S., Worring M., “Detecting CNN-generated facial images in real-world scenarios” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2020), pp. 642–643. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sofer C., Dotsch R., Wigboldus D. H., Todorov A., What is typical is good: The influence of face typicality on perceived trustworthiness. Psychol. Sci. 26, 39–47 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Citron D. K., Franks M. A., Criminalizing revenge porn. Wake For. Law Rev. 49, 345 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu N., Skripniuk V., Abdelnabi S., Fritz M., “Artificial fingerprinting for generative models: Rooting deepfake attribution in training data” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2021), pp. 14448–14457. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkhi O. M., Vedaldi A., Zisserman A., Deep Face Recognition (British Machine Vision Association, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tariq T., Tursun O. T., Kim M., Didyk P., “Why are deep representations good perceptual quality features?” in European Conference on Computer Vision (Springer, 2020), pp. 445–461. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Images have been deposited in GitHub (https://github.com/NVlabs/stylegan2 and https://github.com/NVlabs/ffhq-dataset). Anonymized experimental stimuli and data have been deposited in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ru36d/).