Abstract

Despite demonstrating high levels of academic and professional competence, Asians are underrepresented in leadership roles in North America. The limited research on this topic has found that Asian Americans are perceived by others as poorer leaders than White Americans due to perceptions that Asians lack the ideal traits of a Western leader (i.e., agentic) relative to White Americans. However, we contend that, in addition to poorly activating ideal leader traits, Asian Americans may strongly activate ideal follower traits (e.g., industrious and reliable), and being seen as a good follower may pigeonhole Asian Americans in non-managerial roles. Across 4 studies, our findings generally supported our arguments regarding the activation of ideal follower traits and lack of activation of ideal leader traits for Asian American workers. However, compared to their majority group counterparts, we found some unexpected evidence for a more favorable view of Asian Americans as leaders, which was primarily driven by the greater activation of ideal follower traits (i.e., industry and good citizen) among Asian American workers. Yet, we uncover an important boundary condition in that these “good follower” advantages did not accrue when observers experienced threat—revealing how the benefits of so-called positive stereotypes of Asian American workers are context dependent.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10869-022-09794-3.

Keywords: Asian Americans, Leadership, Stereotypes, Implicit leadership theories, Implicit followership theories

As the modern North American workforce becomes more diverse (Catalyst, 2019; Wilson, 2016), there is a growing call for correspondingly greater racial diversity at the upper echelons of organizations (Alliance for Board Diversity & Deloitte, 2019). In fact, organizations whose leadership team’s ethnic composition mirrors that of its employees tend to perform better and report less interpersonal mistreatment (e.g., Erhardt et al., 2003; Lindsey et al., 2017; Miller & Triana, 2009). However, in trying to improve racial representation in these critical leadership roles, one racial minority group remains underexamined relative to others: Asian Americans. Both in research and practice, important advances have been made toward understanding the leadership challenges faced by other racial minority groups, such as Black or African Americans (e.g., Carton & Rosette, 2011; Linshi, 2014), but relatively little is known regarding the barriers faced by Asian Americans in their advancement to organizational leadership roles.

The emerging, but limited, research on this topic has found that Asian Americans are often perceived by others as poorer leaders than White Americans (e.g., Festekjian et al., 2014; Lai & Babcock, 2013; Landau, 1995; Lu, 2021; Rosette et al., 2008; Sy et al., 2010). Sy et al. (2010) found that poorer perceptions of Asian Americans as leaders may be due to stereotypes that, despite appearing highly competent, Asian Americans lack the assertiveness and extraversion valued for leadership in the West (e.g., Eagly & Karau, 2002; Kono et al., 2012). In addition to perceptions of Asian Americans’ poorer fit with the traits of an ideal leader, we argue that stereotypes of Asian Americans’ hardworking nature and dutifulness (e.g., Berdahl & Min, 2012; Ho & Jackson, 2001) may also activate traits associated with ideal followers. As leadership and followership are traditionally, albeit perhaps inaccurately (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014), viewed as mutually exclusive roles (e.g., Kelley, 1988; Shamir, 2007), Asian Americans being perceived as possessing the traits of an ideal follower relative to other racial groups may lead them to be categorized or viewed as followers to the exclusion of being seen as leaders.

Therefore, in the present paper, we conducted four studies to ascertain whether Asian Americans are unlikely to activate the traits of an ideal Western leader (e.g., agentic and dynamic) as well as are more likely to activate the traits of an ideal Western follower (e.g., hardworking and team oriented) compared to White Americans and whether each pathway uniquely explains the Asian-White leadership gap. First, we examined whether Asian Americans are perceived as lacking (possessing) the traits of an ideal leader (follower) compared to White Americans (Study 1). We then investigated whether failure to activate the traits of an ideal leader as well as activation of the traits of an ideal follower each contributed to the poorer leadership perceptions of Asian Americans relative to their majority group (i.e., White) counterparts (Study 2 and 3). We also analyzed whether Asian Americans who may appear native to North America or have “American” first names and Asian Americans who may appear foreign-born or have Asian first names were perceived differently in these two studies. Finally, we examined threat as a potential moderator or boundary condition of the differential effects we uncovered for Asian versus White employees in the prior studies (Study 4).

The current research makes several important contributions to the literature. First, this research helps advance our understanding of the barriers Asian Americans may face in their advancement to leadership roles, an underexamined issue in the research literature. Specifically, in recent years, scholars have highlighted the need to better understand the leadership experiences of Asian Americans as they face a paradox in their career advancement, where despite being highly qualified, they have low managerial success (e.g., Hewlett et al., 2011). In fact, the term “bamboo ceiling” was coined to highlight the uniqueness of the invisible barriers that Asian Americans face in moving upward in organizations (Hyun, 2005). Indeed, compared to leaders of other racial/ethnic backgrounds, Asian American leaders were the most likely to say that their ethnicity was a weakness in their exercise of leadership (Chin, 2013).

Second, we contribute to the literature by investigating the impact of being perceived as possessing ideal follower-related traits, in addition to ideal leader-related traits, on leadership processes. There have been increasing calls to examine the role of followership in leadership outcomes, especially given the inherent need for leaders to have followers in order to lead (Carsten et al., 2010; Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). However, little is currently empirically known about how followership and leadership concepts work together to influence leadership perceptions (Kim et al., 2021). Therefore, we help to shed much-needed light on the interconnectedness of leadership and followership perceptions.

Finally, we add to the literature by examining potential differences in others’ leadership perceptions of Asian Americans who have “American” versus Asian first names, which may be used to infer whether these individuals were born in North America or were foreign-born. This comparison warrants greater attention given the increasing number of Asians immigrating to North America (López et al., 2017). In fact, the majority of Asians residing in the USA are foreign-born (Pew Research Center, 2015). Prior experimental research often cued that a worker was Asian by interchangeably using either traditionally Asian or American first names (e.g., Ming versus Alex) alongside common East Asian last names (e.g., Chen). However, research suggests that these different kinds of names may generate different reactions and biases, as the “whitened” first name may signal greater acculturation to American culture than the Asian first name (e.g., Kang et al., 2016). Thus, we clarify whether observers view these two groups similarly or differently in this context.

The Asian-White Leadership Gap

Asian Americans’ standing as the most educated racial group in North America (even eclipsing White Americans; Pew Research Center, 2013) may signal that they should face no challenges in attaining career success. Indeed, Asian Americans have a longstanding reputation as a “model minority” (Chao et al., 2013), a group who, despite their racial minority status, has shown impressive levels of competence and success in academic and professional settings (Ho & Jackson, 2001). As a result, Asian Americans are generally assumed to be well equipped to achieve successful careers in lucrative, prestigious occupations (Chao et al., 2013; Yu, 2020).

In recent years, this “model minority” label has been increasingly challenged, with many calling it a myth and arguing that it has been used to maintain and sustain systems of oppression (Chen & Buell, 2018). This is because the Asian American community is highly diverse (López et al., 2017), reflecting over 20 different national origin groups and a range of languages, practices, and different histories of immigration (Zhou & Xiong, 2005). In turn, socioeconomic disparities within this community can be very large, as some groups are highly educated and earn high incomes relative to the population at large (e.g., Japanese, Chinese), whereas other groups have among the lowest levels of educational attainment and incomes within the USA (e.g., Hmong, Cambodian, Vietnamese; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010–2014).

Moreover, when examining Asian Americans’ career advancement to leadership roles, there is reason to believe they may be facing substantial barriers, in line with other racial minority groups. For instance, although constituting approximately 13% of the U.S. professional workforce, Asian Americans only represent 3% of Fortune 500 corporate officers (McGirt, 2019). Additionally, Asian Americans only account for 3.7% of board members for major U.S. corporations, which reflects the lowest representation among racial/ethnic groups (Alliance for Board Diversity & Deloitte, 2019). Even in industries where Asian Americans are overrepresented (e.g., technology), their representation declines from 23 to 16% from the professional to the managerial level (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019). In other words, Asian Americans are underrepresented in leadership roles. Indeed, some research indicates that East Asians reflect the group that is the least likely to be promoted into leadership roles across sectors in North America (Gee & Peck, 2018). As Asians are among the fastest growing racial groups in the U.S. (López et al., 2017), due in part to recent waves of immigration, a better understanding of the leadership obstacles they may face is increasingly crucial.

In fact, the limited, existing research investigating the lack of Asian American representation in organizational leadership roles demonstrates an Asian-White leadership gap. Namely, Asian Americans are often less likely to be selected for leadership roles, rated as having less leadership potential, and perceived to be less effective leaders compared to White Americans (e.g., Festekjian et al., 2014; Galinsky et al., 2013; Lai & Babcock, 2013; Landau, 1995; Sy et al., 2010). Additionally, circumstances where Asian Americans are preferred as leaders (i.e., conditions of poor organizational performance) tend to be short-lived and perceivers do not actually appear to expect Asian American leaders to be successful at leading or changing the negative trajectory the organization is on during these times (Gündemir et al., 2019). Rather, Asian Americans are preferred as leaders when organizations perform poorly because they are assumed to be more self-sacrificing, which may be needed during organizational declines. We note that White Americans are typically the comparison group used in U.S.-based studies as they are generally viewed as the leadership “standard” or default (Gündemir et al., 2019; Rosette et al., 2008). Therefore, we employ them also as the main comparison group in the current study. Specifically, we make the following prediction:

Hypothesis 1: Asian Americans will be perceived as poorer leaders than White Americans.

Race and Activation of Ideal Leader Traits

Individuals have cognitive representations of the traits and behaviors they associate with leaders (Lord et al., 1982). Although individuals vary in the extent to which they endorse various traits as leader-like, the traits most consistently associated with leaders are sensitivity, intelligence, dedication, dynamism, tyranny, and masculinity, i.e., implicit leadership theories (ILTs; Epitropaki & Martin, 2004; Offermann & Coats, 2018). According to leadership categorization theory, the more closely an individual matches the traits viewed as prototypical of a leader in an observer’s mind, the more likely they will be categorized as a leader and be perceived as an effective leader (e.g., Lord & Maher, 1991; Lord et al., 1982, 1984). However, more recent advances based on connectionist principles argue that rather than having a finite number of prototypes that are stored and must be retrieved from memory in this matching process, our cognitive structures representing leadership are also dynamic and responsive to contextual inputs (e.g., Foti et al., 2008; Lord et al., 2001; Shen, 2019). Thus, we argue target race will serve as an important contextual cue that will shape the activation of leadership prototypes and subsequent leadership perceptions.

Within a given context, certain leader traits tend to be perceived as more ideal than others. In North America, agency is seen as especially central to leadership (e.g., Eagly & Karau, 2002; Kono et al., 2012; Vial & Napier, 2018). As a result, individuals who demonstrate the agentic traits or behaviors of a prototypical Western leader (i.e., dynamic, dominant, and masculine) are generally perceived as more leader-like than individuals who do not or who do so to a lesser extent (e.g., Eagly & Karau, 2002; Festekjian et al., 2014; Sy et al., 2010). In other words, there tends to be a relatively stable agentic leadership prototype in the West.

However, connectionist models specify that environmental stimuli, such as target attributes, also serve as inputs into this process and can constrain or activate certain units or concepts (i.e., leadership prototypes), which then shapes leadership perceptions (Braun et al., 2017; Sy et al., 2010). Said otherwise, stereotypes about Asian Americans affect leadership evaluations by suppressing or failing to activate characteristics associated with ideal leaders. Specifically, Asian Americans are typically stereotyped as low on agency (e.g., “non-assertive” and “passive”; Berdahl & Min, 2012; Chin & Kameoka, 2019; Sue et al., 1983). Some authors have argued that perceptions of Asians as passive may be inaccurate and the result of overly narrow, Western views regarding how people exert and enact control within their environment (Spector et al., 2004). Regardless, given the preference for dominant and take-charge leaders in North America, these stereotypes of Asian Americans as lacking agentic traits have been shown to influence perceptions that Asian Americans are less effective leaders than White Americans (e.g., Festekjian et al., 2014; Sy et al., 2010). This is despite the fact that Asian Americans were also stereotyped as highly intelligent and competent (e.g., Festekjian et al., 2014; Sy et al., 2010), as competence was ultimately perceived as less central to leadership effectiveness than agency in a North American context.

Moreover, research indicates that this descriptive view of Asian Americans as lacking in agency is also associated with a prescriptive stereotype, such that Asian Americans who are dominant tend to suffer social sanctions as a consequence (i.e., harassment at work, Berdahl & Min, 2012). This creates a double bind for Asian American workers; low levels of agency may lead others to view them as a poor fit and unsuitable for leadership roles, but high levels of agency tend to be seen as violating norms of how Asians Americans “should” act and engenders backlash. Such backlash may then create additional pressures for Asian American workers to fulfill these stereotypes about their group (Rudman et al., 2012), further reinforcing beliefs that Asian Americans lack agency or are passive. In alignment with these arguments, Asian Canadian university students tend to perceive themselves as more conforming than their White Canadian counterparts (Kim et al., 2021). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2: Asian Americans will be perceived as lacking the traits of an ideal Western leader (i.e., dynamism, tyranny, and masculinity) relative to White Americans.

Hypothesis 3: Perceptions that one possesses the traits of an ideal Western leader (i.e., dynamism, tyranny, and masculinity) will positively predict leadership perceptions.

Race and Activation of Ideal Follower Traits

In addition to failing to activate the traits associated with ideal Western leaders, we theorize that activation of the traits of an ideal Western follower will exert independent effects on the Asian-White leadership gap. Prior research on implicit followership theories (IFTs) has identified the following traits as those most commonly associated with followers: industry, good citizen, enthusiasm, conformity, insubordination, and incompetence (Sy, 2010). Industry, good citizen, and enthusiasm are viewed as prototypical of followers whereas conformity, insubordination, and incompetence are viewed as anti-prototypical of followers (i.e., characteristic of “bad” followers). It is posited that the more an individual possesses traits that correspond with those seen as prototypical of a follower to an observer, the more likely this focal individual will be classified as a follower or be perceived as a good follower (Goswami et al., 2020). Thus, matching perceivers’ views of what constitutes a “good follower” should have important downstream implications for interpersonal relationships at work (Yang et al., 2020). However, based on connectionist principles, individuals’ prototypes of followers are also dynamic and malleable and should be influenced by target attributes, such as race.

Prior research indicates that certain prototypical follower traits are also considered more ideal for followership than others. In the West, ideal followers are most commonly described as loyal team players who proficiently and diligently follow through on tasks (i.e., good citizen, industry, and low in incompetence; e.g., Agho, 2009; Carsten et al., 2010; Junker et al., 2016). Although research reveals that matching the traits one’s leader sees as characteristic of good followers generally results in better leader–follower relations (e.g., leader-member exchange; Kong et al., 2019; Whiteley et al., 2012), it is currently less clear whether being perceived as possessing ideal follower traits will be desirable to attaining leadership roles. Given the tendency for perceivers to view leadership and followership as mutually exclusive roles (e.g., Kelley, 1988; Shamir, 2007), with followership often eliciting negative connotations in the West (e.g., Hoption et al., 2012), we predict that being perceived as an ideal follower may actually harm one’s likelihood of becoming and succeeding as a leader. In other words, stereotypes about Asian Americans may affect leadership evaluations by activating characteristics associated with ideal followers, which may then constrain the activation of leadership concepts in people’s minds.

In a similar vein, Braun and colleagues (2017) argued that being perceived as an ideal follower may inadvertently pigeonhole women in subordinate or non-managerial roles, contributing to women’s underrepresentation in leadership roles. In two studies, these authors demonstrate that women are more strongly associated with ideal followers compared to men. Specifically, women were viewed as being both more relationally oriented (e.g., communicative, team-minded) and task oriented (e.g., responsible, engaged) than men. Thus, in addition to being “pushed” from leadership roles, they argue that women may be being “pulled” toward follower roles. However, it should be acknowledged that these authors did not empirically assess whether and how being perceived as an ideal follower affects leadership evaluations.

We argue that Asian American workers may be subject to a similar process, whereby others may perceive little need to consider higher-level roles for Asian American employees who appear to be “ideal followers” if they are viewed as thriving or a good fit in the lower-level roles they currently occupy. This is because Asian Americans are often stereotyped similarly to women, with both groups being seen as feminine (e.g., Galinsky et al., 2013; Hall et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2012). Consequently, both groups can face similar challenges. For example, both female and Asian American leaders have been found to be subject to the glass cliff phenomenon, preferred as leaders during times of crisis to manage problems but not turn things around (Gündemir et al., 2019; Morgenroth et al., 2020). Additionally, prior research demonstrates that observers tend to assume that Asian Americans will be communal and self-sacrificing to promote cooperation and harmony within the groups that they belong to, including at work, due to presumed collectivistic values characteristic of East Asian cultures (Gündemir et al., 2019). Finally, as a “model minority,” Asian Americans are often stereotyped as competent and hardworking (e.g., Berdahl & Min, 2012; Chao et al., 2013; Sy et al., 2010)—indicating that they will also be seen as possessing the task orientation that generally characterizes ideal followers.

As a result, we hypothesize that relative to White Americans, Asian Americans will be more likely to activate the ideal follower traits of industry, good citizenship, and competence. However, as articulated above, being perceived to possess ideal follower traits may be detrimental to leadership perceptions. Indeed, this coincides with common complaints by Asian Americans that others see them as “great workers, but not leaders” (Sy et al., 2017, p. 150). Therefore, we make the following predictions:

Hypothesis 4: Asian Americans will be perceived as better embodying the traits of an ideal Western follower (i.e., industry, good citizen, and low in incompetence) relative to White Americans.

Hypothesis 5: Perceptions that one possesses the traits of an ideal Western follower (i.e., industry, good citizen, and low in incompetence) will negatively predict leadership perceptions.

Putting the above arguments together and drawing upon connectionist models of leadership perceptions (Braun et al., 2018; Foti et al., 2008; Lord et al., 2001; Sy et al., 2010), we theorize that target race serves as a key contextual input shaping the activation of leadership and followership prototypes, which then affects leadership evaluations. Said otherwise, compared to White Americans, Asian Americans may be perceived as less promising or effective leaders due to two distinct pathways: (1) Asian Americans’ lower likelihood of activating the traits associated with ideal leaders in the West (i.e., dynamism, tyranny, and masculinity) and (2) Asian Americans’ greater likelihood of activating the traits of an ideal follower (i.e., industry, good citizen, and lower on incompetence). In turn, possessing the traits associated with ideal leaders should be positively associated with leadership evaluations. By contrast, possessing the traits associated with ideal followers should be negatively associated with leadership evaluations. In summary, we predict that the activation of ideal leader and follower traits, respectively, will mediate the relationship between race (i.e., Asian American vs. White American) and leadership perceptions. Specifically, we test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6: The relationship between race and leadership perceptions will be mediated by (a) the activation of ideal leader traits (i.e., dynamism, tyranny, and masculinity) and (b) the activation of ideal follower traits (i.e., industry, good citizen, and competence), respectively, such that Asian Americans will be less likely to activate ideal leader traits and more likely to activate ideal follower traits than White Americans, and both paths will explain lower leadership-related ratings and outcomes of Asian Americans.

Asian Americans with “American” Versus Asian First Names

As the Asian population in North America continues to grow (López et al., 2017), it is important to examine whether views of Asians with an “American” name compared to an Asian name may differ, especially given the common practice of Asians using an “American” first name over their Asian one (Heffernan, 2010). In fact, a study by Kang et al. (2016) suggests that Asian Americans with “whitened” first names, such as “Luke Zhang,” may be judged differently from Asian Americans with Asian first names, such as “Lei Zhang.” Specifically, “Luke” was more likely to receive call-backs for a job interview than “Lei.” This is presumably due to “whitened” names signaling a greater assimilation to the mainstream majority group than more “foreign” sounding names, thereby reducing the activation of outgroup stereotypes associated with Asian Americans. As such, if a “whitened” first name, as opposed to an Asian first name, generates views of greater assimilation with Western culture, viewers may expect an Asian individual with an “American” first name to be potentially more agentic, thereby making this Asian individual seem better suited for leadership roles. We therefore predict the following:

Hypothesis 7: Compared to Asian Americans with an Asian first name, Asian Americans with an “American” first name may be more likely to activate the traits of an ideal leader and less likely to activate the traits of an ideal follower, thereby making them seem better suited as leaders.

Study 1: Racial Groups and the Activation of Ideal Leader and Ideal Follower Traits

As a first step, we aimed to find initial support regarding the activation of ideal leader traits (Hypothesis 2) and ideal follower traits (Hypothesis 4) about Asian Americans. Additionally, given that stereotypes of Asian Americans differ from those of other racial minority groups in the U.S. (e.g., Black Americans and Hispanic Americans), as well as the racial majority group (i.e., White Americans), we sought to examine whether this pattern of leader and follower trait activation is unique to Asian Americans.

Method

Participants

Participants living in the USA were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk; Buhrmester et al., 2011) and were remunerated 1.00 USD for their participation. Given that we used an online panel, we sought to ensure high-quality data by identifying and removing potentially problematic respondents. Based on best practice recommendations indicating that removing valid responses may be more problematic than including potentially careless responses (Curran, 2016), we only excluded participants who were identified as problematic based on multiple indicators (n = 9). Specifically, participants were excluded if they responded to the survey in an extremely short amount of time (i.e., an average of less than 2 s per item) and demonstrated poor individual consistency on psychometrically similar items (Curran, 2016; DeSimone et al., 2015; Maniaci & Rogge, 2014).1 Thus, we used this combination of indicators as they would help detect the type of responder that would be particularly problematic to this study (i.e., random responders). Our final sample therefore consisted of 213 participants, with 100 (47%) females, 112 (52%) males, and 1 unspecified (1%). Among participants, 158 (74%) self-identified as White, 20 (9%) as Black, 16 (8%) as Hispanic or Latino, 15 (7%) as Asian, and 4 (2%) as another or more than one ethnicity. The mean age of participants was 38 years (SD = 11). On average, participants had 17.5 years (SD = 11) of work experience.

Procedure

A between-participants design was used where each participant was randomly assigned to rate one of four target racial groups: White American (n = 48), Asian American (n = 53), Black American (n = 56), or Hispanic American (n = 56). After consenting to the study, participants rated members of their assigned target racial group on measures of traits associated with leaders and followers, then completed demographic questions. The order of the leader and follower trait measures was randomized to reduce potential order effects.

Measures

Leader Traits

Epitropaki and Martin’s (2004) Implicit Leadership Theories (ILT) scale was used to assess traits associated with leaders. Participants rated how characteristic each trait was of members of their randomly assigned racial group on a nine-point Likert scale (1 = not at all characteristic; 9 = extremely characteristic). We focused on traits that were relevant to our hypotheses, i.e., dynamism (ɑ = .91; energetic, strong, dynamic), tyranny (ɑ = .91; domineering, pushy, manipulative, loud, selfish, conceited), and masculinity (ɑ = .88; masculine, male).

Follower Traits

Sy’s (2010) Implicit Followership Theories (IFT) scale was used to assess traits associated with followers. Participants rated how characteristic each trait was of members of their randomly assigned racial group on a nine-point Likert scale (1 = not at all characteristic; 9 = extremely characteristic). Specifically, we assessed industry (ɑ = .95; hardworking, productive, goes above and beyond), good citizen (ɑ = .91; loyal, reliable, team player), and incompetence (ɑ = .90; uneducated, slow, inexperienced).

Covariates

All analyses controlled for participant race to account for potential differences between racial groups in their perceptions of Asians. Participant race was dummy coded (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic, and Other), with Asian as the reference group.

Results

Before testing our hypotheses, we first tested for the presence of common method variance (CMV) in Study 1. If the presence of CMV is found to affect substantive relationships, CMV needs to be accounted for when testing hypotheses (Williams & McGonagle, 2016). Although there was some evidence of CMV in Study 1, it did not affect substantive relationships among study variables. Thus, based on the recommendations and guidelines outlined by Williams and McGonagle (2016), there was no need to model CMV in our subsequent analyses (additional details can be found in our Supplementary Online Materials).

Descriptive statistics and correlations for Study 1 variables are presented in Table 1. ANCOVA omnibus F-tests were significant for all leader traits except dynamism, F(3, 205) = 1.26, p = .288 (see Table 2). Hypothesis 2 predicted that Asian Americans would be viewed as less dynamic, tyrannical, and masculine than White Americans. Results from Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc analyses provided partial support for this hypothesis. Specifically, compared to White Americans, Asian Americans were rated lower on tyranny (Asian: M = 2.82, SE = 0.69; White: M = 4.08, SE = 0.67), t(205) = 3.89, p < .001, and masculinity (Asian: M = 3.81, SE = 0.67; White: M = 5.09, SE = 0.65), t(205) = 4.06, p < .001, but similarly on dynamism (Asian: M = 6.71, SE = 0.69; White: M = 6.14, SE = 0.67), t(205) = − 1.76, p = .476.

Table 1.

Study 1: Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for leader and follower traits

| Variable | Descriptives | Bivariate correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| Leader | 1 | Dynamism | 6.45 | 1.61 | (.91) | |||||

| 2 | Tyranny | 4.66 | 1.75 | − .17* | (.91) | |||||

| 3 | Masculinity | 5.18 | 1.67 | − .07 | .45*** | (.88) | ||||

| Follower | 4 | Industry | 6.44 | 1.77 | .68*** | − .39*** | − .22** | (.95) | ||

| 5 | Good citizen | 6.30 | 1.74 | .67*** | − .42*** | − .18** | .80*** | (.91) | ||

| 6 | Incompetence | 3.87 | 1.80 | − .41*** | .53*** | .34*** | − .60*** | − .58*** | (.90) | |

Note. n = 213. Means are on a scale of 1 to 9. Values in the diagonal are Cronbach alpha reliabilities

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Table 2.

Study 1: Estimated means and racial group comparisons for leader and follower traits

| Trait | F | p | White American | Asian American | Black American | Hispanic American | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||||

| Leader | Dynamism | 1.26 | .288 | 6.14a | 0.67 | 6.71a | 0.69 | 6.66a | 0.66 | 6.54a | 0.69 |

| Tyranny | 10.56 | < .001 | 4.08b,d | 0.67 | 2.82a | 0.69 | 4.35c,d | 0.67 | 3.17a | 0.69 | |

| Masculinity | 10.16 | < .001 | 5.09a | 0.65 | 3.81b | 0.67 | 5.39a | 0.65 | 4.97a | 0.67 | |

| Follower | Industry | 12.47 | < .001 | 6.83b,d | 0.68 | 7.90a | 0.70 | 6.00c,d | 0.67 | 7.22a,b | 0.70 |

| Good citizen | 8.26 | < .001 | 6.64a,c | 0.69 | 7.47a,b | 0.71 | 5.87c | 0.68 | 6.60c | 0.71 | |

| Incompetence | 14.55 | < .001 | 2.63a | 0.68 | 1.49b | 0.70 | 3.54c | 0.67 | 2.93a,c | 0.70 | |

Note. All F-tests have dfrace = 3 and dferror = 205. Means are on a scale of 1 to 9. For each row, means with different superscripts are significantly different from each other by at least p < .05. Means estimated at 0.50 for each dummy variable (i.e., Black = 0.50, Hispanic = 0.50, White = 0.50, and Other = 0.50). nWhite = 48, nAsian = 53, nBlack = 56, nHispanic = 56

ANCOVA omnibus F-tests were significant for all three ideal follower traits (see Table 2). Hypothesis 4 predicted that Asian Americans would be viewed as more industrious, better citizens, and less incompetent than White Americans. Results from Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc analyses provided support for this hypothesis, except for good citizen. Namely, compared to White Americans, Asian Americans were rated higher on industry (Asian: M = 7.90, SE = 0.70; White: M = 6.83, SE = 0.68), t(205) = − 3.23, p = .009, and lower on incompetence (Asian: M = 1.49, SE = 0.70; White: M = 2.63, SE = 0.68), t(205) = 3.46, p = .004, but similarly on good citizen (Asian: M = 7.47, SE = 0.71; White: M = 6.64, SE = 0.69), t(205) = − 2.48, p = .083, compared to White Americans.

Supplementary Analyses

Two other racial minority groups, Black Americans and Hispanic Americans, were included in this study to examine whether patterns observed among Asian Americans on ideal leader and follower traits may be unique to this group or characteristic of other racial minorities as well. Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparisons revealed that, for ideal leader traits, Asian Americans, Black Americans, Hispanic Americans, and White Americans were rated similarly on dynamism; however, Asian Americans were rated as less tyrannical than White Americans and Black Americans, but similarly on tyranny as Hispanic Americans. Asian Americans were also rated as the least masculine compared to other groups. For ideal follower traits, Asian Americans were rated as more industrious than White Americans and Black Americans, but similarly industrious as Hispanic Americans. Asian Americans were also rated significantly higher on good citizen than Black Americans and Hispanic Americans, but rated similarly on good citizen as White Americans. Finally, Asian Americans were rated as the least incompetent among all groups (see Table 2). Asian Americans therefore generally activated ideal leader and follower traits—less agentic and more loyal and competent, respectively—in ways that differ from other racial minority, and racial majority, groups in the USA.

Discussion

Study 1 reveals some evidence that Asian Americans activated ideal leader and ideal follower traits as theorized. Specifically, for ideal leader traits, Asian Americans were perceived as less tyrannical and masculine relative to White Americans, suggesting they failed to activate key ideal leader characteristics. Additionally, for ideal follower traits, Asian Americans were perceived as highly industrious and less incompetent than White Americans, suggesting they activated ideal follower traits. Moreover, the pattern of leader and follower traits that were activated for Asian Americans appeared to be unique to this group, which supports findings that Asian Americans are perceived differently from other racial minority groups (Butz & Yogeeswaran, 2011; Chao et al., 2013). Therefore, we found further justification for the need to examine the potentially unique leadership challenges of Asian Americans on their own rather than as a part of the broader grouping of racial minorities.

Study 2: Activation of Ideal Leader and Ideal Follower Traits on Leadership Effectiveness

In Study 2, we examined the impact of Asian-White differences in the activation of traits associated with ideal leaders and ideal followers on leadership effectiveness. We first aimed to replicate Sy et al.’s (2010) findings that Asian Americans are perceived as less effective leaders than White Americans due to views that Asian Americans are less likely to activate the agentic traits of an ideal leader. Second, we sought to test our predictions that Asian Americans’ greater activation of the traits of an ideal follower than White Americans would also exert distinct effects on the Asian-White leadership gap. Third, as described previously, we also examined participants’ perceptions of Asian Americans with “American” vs. Asian first names, which may be used by evaluators as a signal of nativity versus foreign-born status or degree of acculturation to the dominant culture, given ambiguity regarding whether this factor will affect evaluations.

Method

Participants

Participants living in the USA were recruited from MTurk and were remunerated 1.00 USD for their participation. Note that participants in each study are non-overlapping. Participants were first removed from analyses if they failed manipulation checks regarding the sex and race of the individual described in the vignette (n = 165), indicating they did not experience the manipulation as intended. We also sought to identify additional problematic or careless respondents. In this study, we also incorporated attention checks. Therefore, we removed participants who responded to the survey in an amount of time that suggests they may not have read our vignette or responded to items carefully, demonstrated poor individual consistency on conceptually similar items, and failed more than half of the attention checks (e.g., “Please select 40%”; Curran, 2016; DeSimone et al., 2015; n = 4).2 As a result, the final sample size was 319, with 130 (41%) females, 183 (57%) males, and 6 (2%) unspecified. The majority of participations self-identified as White (251; 79%), 25 (8%) as Black, 15 (5%) as Hispanic or Latino, 20 (6%) as East/Southeast Asian, and 5 (2%) as other or more than one ethnicity. The mean age of participants was 37 years (SD = 12). On average, participants had 18 years (SD = 12) of work experience.

Procedure

A between-participants vignette design was used whereby each participant was randomly assigned to one of three conditions: White American (n = 122), Asian American with “American” first name (n = 87), or Asian American with Asian first name (n = 110). Vignette designs are appropriate to examine our research questions as they provide mundane realism by describing a real-world scenario, but also allow researchers to manipulate the variables of interest (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014).

Our study procedures drew on Sy et al.’s (2010) as we aimed to replicate their findings regarding ideal leader traits. In each condition, upon consenting to the study, participants read a vignette about a fictional manager from a U.S.-based organization. The manager was described in general terms. The manager's race was manipulated both by the manager’s name (i.e., John Davis, David Wong, or Tung-Sheng Wong) and the description of his race (i.e., White American or Asian American). All managers depicted were male to hold constant any gender effects. Participants then rated the manager on leadership effectiveness as well as perceived standing on ideal leader and ideal follower traits. Measures of ideal leader and ideal follower traits were randomized to reduce potential order effects.

The vignette consisted of the following description:

David Wong (Tung-Sheng Wong/John Davis), a 31-year-old Asian (Asian/White) American male, graduated in 2008 from University of Arizona. He has been employed as a manager in the same U.S.-based organization for five years. His responsibilities include managing customer complaints, providing consultation regarding the company’s services, and troubleshooting problems. Although he sometimes has problems with certain co-workers, he is generally good tempered.

Measures

To ensure our measures accurately captured judgements of different groups, we used a “common rule” framing, as recommended by Biernat and Manis (1994). When making judgements about members of a group using subjective response scales, such as Likert scales, evaluators may shift their standards. For example, when asked how masculine David Wong is, evaluators may compare him to other Asian Americans rather than the average American, masking the impact of stereotypes (e.g., he’s masculine for an Asian American). However, this shift in standards is less likely when using objective response formats, such as percentiles, which inherently involve judging a target relative to the population. Thus, in the current study, participants were specifically instructed to compare the target manager to a specific population (i.e., all U.S.-based managers) on a percentile scale (0–100%).

Leadership Effectiveness

Following Sy et al. (2010), we used the Global Leadership Impression (GLI) scale (5 items; ɑ = .94; Cronshaw & Lord, 1987) to assess leadership effectiveness. A sample item is: “How well does David Wong (Tung-Sheng Wong/John Davis) engage in leader behavior?” Participants responded using percentiles from 0–100%.

Leader and Follower Traits

The ILT scale (Epitropaki & Martin, 2004) was used to assess activation of ideal leader traits: dynamism (ɑ = .93), tyranny (ɑ = .94), and masculinity (ɑ = .60). The IFT scale (Sy, 2010) was used to assess activation of ideal follower traits: industry (ɑ = .92), good citizen (ɑ = .92), and incompetence (ɑ = .91). Participants responded on a percentile scale from 0–100%.

Covariates

All analyses controlled for participant race which was dummy coded (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic, and Other), with Asian as the reference group.

Results

Before testing our hypotheses, we first tested for the presence of CMV, as all variables were assessed at the same time. Although there was some evidence of CMV, using the methods outlined by Williams and McGonagle (2016), it was found not to affect substantive relationships between study variables. Thus, it was not necessary to account for CMV in testing hypotheses (additional details can be found in the Supplementary Online Materials).

Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables for Study 2 are presented in Table 3. We predicted that Asian Americans would be perceived as less effective leaders than White Americans (Hypothesis 1). However, the ANCOVA omnibus F-test for GLI was not significant, F(2, 309) = 0.55, p = .578 (see Table 4). Thus, leadership effectiveness ratings did not significantly differ across the three groups, and Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

Table 3.

Study 2: Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for leadership effectiveness and leader and follower traits

| Variable | Descriptives | Bivariate correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| 1 | Leadership effectiveness | 64.70 | 16.99 | (.94) | |||||||

| Leader | 2 | Dynamism | 64.35 | 17.80 | .66*** | (.93) | |||||

| 3 | Tyranny | 38.10 | 20.63 | − .20*** | − .08 | (.94) | |||||

| 4 | Masculinity | 74.94 | 18.49 | .32*** | .43*** | .09 | (.60) | ||||

| Follower | 5 | Industry | 71.25 | 16.39 | .67*** | .76*** | − .19*** | .40*** | (.92) | ||

| 6 | Good citizen | 70.79 | 17.41 | .69*** | .75*** | − .28*** | .36*** | .82*** | (.92) | ||

| 7 | Incompetence | 18.18 | 18.37 | − .30*** | − .34*** | .42*** | − .32*** | − .45*** | − .42*** | (.91) | |

Note. n = 319. Means are on a percentile scale of 0–100%. Values in the diagonal are Cronbach alpha reliabilities

***p < .001

Table 4.

Study 2: Estimated means and racial group comparisons for leadership effectiveness and leader and follower traits

| Trait | F | p | Asian American with “American” name | White American | Asian American with Asian name | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||||

| Leadership effectiveness | 0.55 | .578 | 71.27a | 6.29 | 71.12a | 6.23 | 69.05a | 6.35 | |

| Leader | Dynamism | 0.21 | .809 | 69.03a | 6.54 | 70.61a | 6.49 | 70.39a | 6.60 |

| Tyranny | 2.11 | .124 | 24.19a | 7.44 | 28.91a | 7.37 | 23.97a | 7.50 | |

| Masculinity | 2.78 | .063 | 86.97a | 6.67 | 91.87a | 6.61 | 86.79a | 6.72 | |

| Follower | Industry | 2.27 | .105 | 83.34a | 6.26 | 80.91a | 6.19 | 85.50a | 6.30 |

| Good citizen | 0.74 | .478 | 85.73a | 6.67 | 83.76a | 6.59 | 86.47a | 6.71 | |

| Incompetence | 3.58 | .029 | 1.71a | 6.79 | 8.50b | 6.70 | 5.43a,b | 6.82 | |

Note. F-test for leadership effectiveness has dfrace = 2 and dferror = 309, F-tests for leader traits have dfrace = 2 and dferror = 308, and F-tests for follower traits have dfrace = 2 and dferror = 306. Means are on a percentile scale of 0–100%. For each row, means with different superscripts are significantly different from each other by at least p < .05. Means estimated at 0.50 for each dummy variable (i.e., Black = 0.50, Hispanic = 0.50, White = 0.50, and Other = 0.50). nAsian American with “American” name = 87, nWhite American = 122, nAsian American with Asian name = 110

All ANCOVA omnibus F-tests for ideal leader and follower traits were non-significant, except for the follower trait of incompetence, F(2, 306) = 3.58, p = .029 (see Table 4). Therefore, our hypothesis on the effect of race on ideal leader traits (Hypothesis 2) was not supported. Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparisons showed that the Asian American manager with the “American” first name (M = 1.71, SE = 6.79) was perceived as less incompetent than the White American manager (M = 8.50, SE = 6.70), t(306) = 2.67, p = .024. The Asian American manager with the Asian first name (M = 5.43, SE = 6.82) was rated similarly to both the White American manager, t(306) = − 1.31, p = .573, and the Asian American manager with the “American” first name, t(306) = 1.44, p = .453. Therefore, our hypothesis on the effect of race on ideal follower traits (Hypothesis 4) was partially supported.

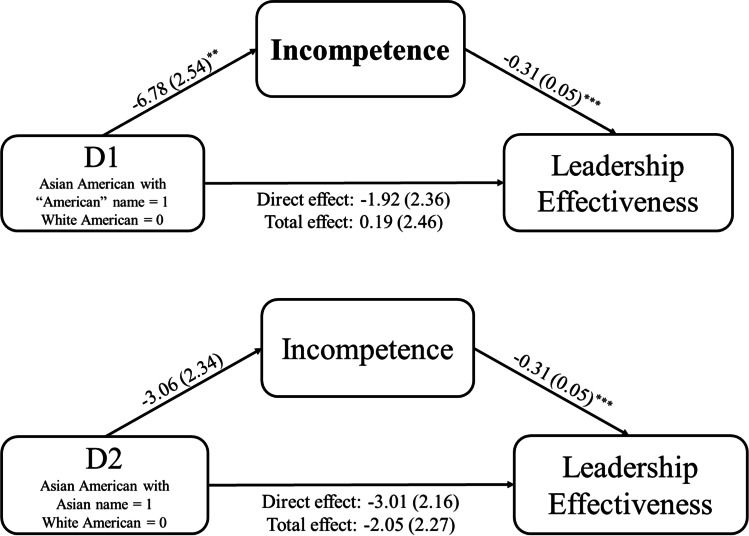

Contrary to Hypothesis 5 that predicted that the traits of an ideal Western follower (e.g., low in incompetence) will negatively predict leadership perceptions, we found that being high in incompetence negatively predicted leadership effectiveness, b = − 0.31, SE = 0.05, p < .001 (see Fig. 1). Hypothesis 6 predicted that Asian Americans would be perceived as poorer leaders than White Americans due to differences in the activation of ideal leader and follower traits. As our results showed that the two Asian American managers and the White American manager were rated similarly on leadership effectiveness, Hypothesis 6 was not supported. However, we continued to examine whether incompetence may still mediate the effect of race on leadership perceptions. We used bias-corrected confidence intervals derived from bootstrapping 5000 samples (Hayes, 2018; Rosseel, 2012) and dummy-coded race with the White American employee as the reference group.

Fig. 1.

Indirect effects between race and leadership effectiveness via follower trait in Study 2. Note. Race was dummy coded as D1 and D2 with White American as the reference group. Indirect effects were tested in the same model but are presented separately here for readability. Significant mediators are in boldface. Numbers before parentheses are B weights derived from bootstrap procedures. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. All analyses control for participant race (dummy coded as Black, Hispanic, White, and Other, with Asian as the reference group). *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

As shown in Table 5, when comparing the Asian American manager with the “American” first name and the White American manager, the effect of race on leadership effectiveness was significantly mediated by incompetence, indirect effect = 2.11, 95% CI [0.72, 3.85]. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 1, the Asian American manager with the “American” first name was seen as less incompetent than the White American manager, and incompetence was negatively related to leadership effectiveness. When comparing the Asian American manager with the Asian first name and the White American manager, incompetence did not significantly mediate the effect of race on leadership effectiveness, indirect effect = 0.95, 95% CI [− 0.48, 2.64].

Table 5.

Study 2: Mediation: incompetence mediating the effect of race on leadership effectiveness

| Trait | D1: Asian American with “American” name vs. White American | D2: Asian American with Asian name vs. White American | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | 95% CI | Indirect effect | 95% CI | ||||||

| Coefficient | SE | Lower | Upper | Coefficient | SE | Lower | Upper | ||

| Follower | Incompetence | 2.11 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 3.85 | 0.95 | 0.79 | − 0.48 | 2.64 |

Note. Race was dummy coded with White Americans as the reference group, i.e., D1: Asian American with “American” first name = 1, White American = 0; D2: Asian American with Asian first name = 1, White American = 0. Bootstrap sample size = 5000. Coefficients in boldface indicate significant mediation

Note Hypothesis 7 predicted that, compared to the Asian American manager with the Asian first name, the Asian American manager with the “American” first name will be viewed as a better fit with the ideal leader traits and a poorer fit with the ideal follower traits, thereby making him seem better suited for a leadership role. Our results do not support this hypothesis as both Asian American managers were rated similarly across all leader and follower traits, and they were perceived similarly on leadership effectiveness.

Discussion

The first purpose of this study was to replicate Sy et al.’s (2010) findings. Despite using a similar paradigm, we did not replicate their results regarding group differences on leadership perceptions and activation of ideal agentic leader traits. A potential reason may be that, unlike Sy and colleagues, we modified our measures to employ a common-rule framing. However, conceptually, this should have enhanced our ability to detect stereotype-based judgements. We therefore speculate that context may have driven the differing findings between our study and Sy et al.’s (2010) study. Specifically, their participants were recruited from the Los Angeles area of California, which has a higher concentration of Asians (15%) compared to the national prevalence (6%; U.S. Census Bureau, 2018). In contrast, our sample was unlikely to have been localized to one region in the USA. Thus, perhaps stereotypes about Asians were more salient among the Californian sample given the greater number of Asians in that area.

The second purpose of this study was to examine whether differential activation of ideal follower traits across groups contributes to the poorer perceptions of Asian Americans relative to White Americans as leaders. However, in the current study, Asian American and White American managers were only rated differently on incompetence. This may have occurred because the target being evaluated was already in a managerial or leadership position, thereby generally making traits associated with followers less salient. We further examine this possibility in Study 3.

Study 3: Activation of Ideal Leader and Ideal Follower Traits on Leadership Potential

In Study 3, we aimed to ascertain whether we did not observe the predicted Asian-White leadership gap in the prior study because the individual described in the vignette already held a managerial role. In other words, participants may have assumed that the Asian American manager possessed the leader characteristics necessary for this position, leading to similar perceptions of the Asian American and White American managers. Additionally, we may not have observed group differences on ideal follower traits because followership may not have been especially salient in a situation where the individual being observed is already a leader. To test these possibilities, in Study 3, we moved to a scenario where the individual being evaluated is in a subordinate or non-managerial role and is being considered for a promotion to a managerial or leadership role. We again differentiated between Asian American applicants who had an “American” versus Asian first name to investigate whether the two Asian American applicants are evaluated similarly or differently.

Method

Participants

U.S.-based participants were recruited from MTurk and were remunerated 1.00 USD for their participation. Participants were removed for failing manipulations checks (n = 101) as well as based on multiple indicators suggesting their responses are likely careless or problematic using the same criteria as Study 2 (n = 1).3 Therefore, the final sample consisted of 310 participants, with 151 (49%) females, 155 (50%) males, and 4 (1%) unspecified. Among participants, 212 (68%) self-identified as White, 39 (13%) as Black, 21 (7%) as Hispanic or Latino, 25 (8%) as East/Southeast Asian, and 11 (4%) as another or more than one ethnicity. The mean age of participants was 35 years (SD = 11 years). On average, participants had 16 years (SD = 13 years) of work experience.

Procedure

A between-participants experimental design was used whereby participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: White American (n = 109), Asian American with “American” first name (n = 99), or Asian American with Asian first name (n = 102). After consenting to the study, participants read a vignette about a fictional male employee and rated the employee on leadership potential and standing on ideal leader and ideal follower traits, the latter of which were randomized to reduce potential order effects. The vignette was adapted from Study 2 such that the employee’s responsibilities described a non-managerial role:

David Wong (Tung-Sheng Wong/John Davis), a 31-year-old Asian (Asian/White) American male, graduated in 2010 from University of Arizona. He has been employed as an analyst in the same U.S.-based organization for four years. His responsibilities include preparing proposals and reports, providing consultation regarding the company's services, and responding to client complaints. Although he sometimes has problems with certain co-workers, he is generally good tempered.

Measures

All measures used a common-rule framing (Biernat & Manis, 1994), and participants were asked to respond using a percentile scale (0–100%). In this study, we changed the referent group to U.S.-based employees with the same level of work experience.

Leadership Potential

We used Mueller et al.’s (2011) measure (4 items; ɑ = .96). Sample items include “has the potential to become an effective leader” and “has the potential to advance to a leadership position.” Participants responded on a percentile scale from 0–100%.

Leader and Follower Traits

The ILT (Epitropaki & Martin, 2004) and IFT (Sy, 2010) scales were used to assess standing on leader and follower traits, respectively. ILT dimensions assessed were dynamism (ɑ = .91), tyranny (ɑ = .94), and masculinity (ɑ = .51).4 IFT dimensions assessed were industry (ɑ = .94), good citizen (ɑ = .89), and incompetence (ɑ = .94). Participants responded on a percentile scale from 0–100%.

Covariates

All analyses controlled for participant race which was dummy coded (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic, and Other), with Asian as the reference group.

Results

Before testing our hypotheses, we first examined whether there was evidence of CMV. Although there was some evidence that CMV was present in this dataset, subsequent analyses as recommended by Williams and McGonagle (2016) indicated that it did not affect substantive relationships between study variables. Therefore, we did not need to account for CMV as it would not bias our ability to detect relationships of interest when testing study hypotheses (additional details can be found in Supplementary Online Materials).

Descriptive statistics and correlations between Study 3 variables are presented in Table 6. Hypothesis 1 predicted that Asian Americans will be perceived as poorer leaders than White Americans. ANCOVA omnibus F-tests showed that target employee race had a significant effect on leadership potential, F(2, 301) = 7.22, p < .001 (see Table 7). However, Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparisons showed that the Asian American employee with the “American” first name (M = 87.65, SE = 5.45) was perceived as having stronger leadership potential than the White American employee (M = 78.36, SE = 5.36), t(301) = 3.70, p < .001, failing to support Hypothesis 1. The Asian American employee with the Asian first name (M = 84.66, SE = 5.32) was also rated as having greater leadership potential than the White American employee, t(301) = 2.51, p = .038 and was rated similarly to the Asian American employee with the “American” first name, t(301) = 1.17, p = .734.

Table 6.

Study 3: Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for leadership potential and leader and follower traits

| Variable | Descriptives | Bivariate correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| 1 | Leadership potential | 66.65 | 18.72 | (.96) | |||||||

| Leader | 2 | Dynamism | 65.36 | 17.24 | .62*** | (.91) | |||||

| 3 | Tyranny | 40.44 | 23.35 | − .16** | − .03 | (.94) | |||||

| 4 | Masculinity | 74.65 | 17.11 | .27*** | .36*** | .13* | (.51) | ||||

| Follower | 5 | Industry | 72.46 | 16.63 | .71*** | .67*** | − .24*** | .28*** | (.94) | ||

| 6 | Good citizen | 70.38 | 17.26 | .72*** | .65*** | − .38*** | .23*** | .79*** | (.89) | ||

| 7 | Incompetence | 19.80 | 22.48 | − .16** | − .08 | .56*** | − .13* | − .28*** | − .22*** | (.94) | |

Note. n = 310. Means are on a percentile scale of 0–100%. Values in the diagonal are Cronbach alpha reliabilities

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Table 7.

Study 3: Estimated means and racial group comparisons for leadership potential and leader and follower traits

| Trait | F | p | Asian American with “American” name | White American | Asian American with Asian name | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||||

| Leadership potential | 7.22 | < .001 | 87.65a | 5.45 | 78.36b | 5.36 | 84.66a | 5.32 | |

| Leader | Dynamism | 1.41 | .246 | 73.06a | 5.21 | 69.47a | 5.10 | 72.71a | 5.08 |

| Tyranny | 16.65 | < .001 | 43.94a | 6.75 | 61.69b | 6.61 | 54.09c | 6.58 | |

| Masculinity | 2.91 | .056 | 80.60a | 5.14 | 86.23a | 5.03 | 83.12a | 5.01 | |

| Follower | Industry | 5.86 | .003 | 82.60a | 4.92 | 74.98b | 4.83 | 79.79a,b | 4.80 |

| Good citizen | 5.49 | .005 | 83.05a | 5.10 | 75.31b | 5.01 | 79.60a,b | 4.98 | |

| Incompetence | 6.78 | .001 | 26.88a | 6.54 | 37.90b | 6.43 | 31.59a,b | 6.39 | |

Note. F-tests for leadership potential and industry have dfrace = 2 and dferror = 301 and F-tests for all other traits have dfrace = 2 and dferror = 300. Means are on a percentile scale of 0–100%. For each row, means with different superscripts are significantly different from each other by at least p < .05. Means estimated at 0.50 for each dummy variable (i.e., Black = 0.50, Hispanic = 0.50, White = 0.50, and Other = 0.50). nAsian American with “American” name = 99, nWhite American = 109, nAsian American with Asian name = 102

For ideal leader traits, race had a significant effect on tyranny, F(2, 300) = 16.65, p < .001, but not dynamism and masculinity (see Table 7). Partially supporting Hypothesis 2, that Asian Americans will be perceived as less ideal agentic leaders than White Americans, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc results showed that the Asian American employee with the “American” first name (Asian: M = 43.94, SE = 6.75; White: M = 61.69, SE = 6.61), t(300) = − 5.76, p < .001, and the Asian American employee with the Asian first name (Asian: M = 54.09, SE = 6.58; White: M = 61.69, SE = 6.61), t(300) = − 2.47, p = .042, were rated as less tyrannical than the White American employee. For ideal follower traits, race had a significant effect on all three traits (see Table 7). In full support of Hypothesis 4 that Asian Americans will activate traits associated with ideal followers, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc results showed that the Asian American employee with the “American” first name was rated as more industrious (Asian: M = 82.60, SE = 4.92; White: M = 74.98, SE = 4.83), t(301) = 3.37, p = .003, a better citizen (Asian: M = 83.05, SE = 5.10; White: M = 75.31, SE = 5.01), t(300) = 3.30, p = .003, and less incompetent (Asian: M = 26.88, SE = 6.54; White: M = 37.90, SE = 6.43), t(300) = − 3.66, p < .001, than the White American employee. Interestingly, our findings on ideal follower traits indicated that ratings of the Asian American employee with the Asian first name did not significantly differ from ratings of the Asian American employee with the “American” first name or the White American employee, as their ratings generally fell between the two groups.

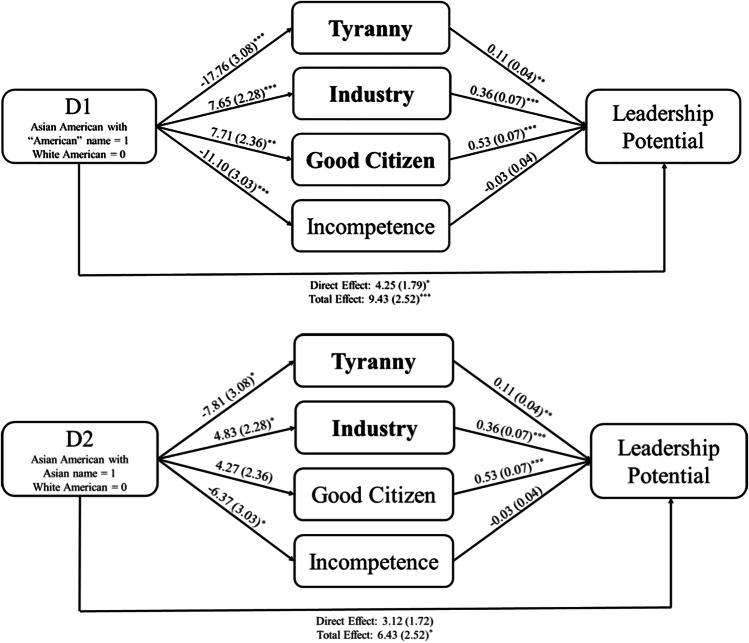

As predicted in Hypothesis 3 that traits associated with ideal leaders in the West will positively predict leadership perceptions, tyranny was positively related to perceptions of leadership potential, b = 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = .006 (see Fig. 2). However, contrary to Hypothesis 5 that activating ideal follower traits would pigeonhole Asian American workers, industry, b = 0.36, SE = 0.07, p < .001, and good citizen, b = 0.53, SE = 0.07, p < .001, were also positively related to perceptions of leadership potential.

Fig. 2.

Indirect effects between race and leadership potential via leader and follower traits in Study 3. Note. Race was dummy coded as D1 and D2 with White American as the reference group. Indirect effects were tested in the same model but are presented separately here for readability. Significant mediators are in boldface. Numbers before parentheses are B weights derived from bootstrap procedures. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. All analyses control for participant race (dummy coded as Black, Hispanic, White, and Other, with Asian as the reference group). *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Hypothesis 6 predicted that Asian Americans would be perceived as poorer leaders than White Americans due to differences in the activation of ideal leader and follower traits. As our results showed that the Asian American employee was rated higher on leadership potential than the White American employee, Hypothesis 6 is not supported. We therefore examined whether Asian-White differences in the activation of ideal leader and follower traits may have increased, rather than decreased, Asian Americans’ perceived suitability for leadership. Specifically, we tested the indirect effect of target race on leadership potential via ideal leader and follower traits (in parallel) that showed significant group differences. We used bias-corrected confidence intervals derived from bootstrapping 5000 samples (Hayes, 2018; Rosseel, 2012) and dummy-coded race with the White American employee as the reference group.

As shown in Table 8, when comparing the Asian American employee with the “American” first name and the White American employee, we found that the effect of race on leadership potential was significantly mediated by the ideal leader trait of tyranny, indirect effect = − 1.97, 95% CI [− 3.93, − 0.43], and two ideal follower traits, i.e., industry, indirect effect = 2.76, 95% CI [0.78, 5.17], and good citizen, indirect effect = 4.07, 95% CI [1.52, 7.29]. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 2, the Asian American employee with the “American” first name was seen as more industrious and a better citizen than the White American employee, and each of these characteristics was positively related to leadership potential. However, it should be noted that the Asian American employee with the “American” first name was also rated as less tyrannical than the White American employee, and tyranny was positively related to leadership potential. Thus, although the Asian American employee was ultimately rated higher in leadership potential due to his higher perceived standing as an ideal hardworking follower, a lower perceived standing on being an ideal take-charge leader was harmful to his leadership outcomes. Finally, when comparing the Asian American employee with the Asian first name with the White American employee, we found significant indirect effects in the same directions for tyranny and industry as when comparing the Asian American employee with the “American” first name with the White American employee (see Fig. 2).

Table 8.

Study 3: Parallel mediation: leader and follower traits mediating the effect of race on leadership potential

| Trait | D1: Asian American with “American” name vs. White American | D2: Asian American with Asian name vs. White American | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | 95% CI | Indirect effect | 95% CI | ||||||

| Coefficient | SE | Lower | Upper | Coefficient | SE | Lower | Upper | ||

| Leader | Tyranny | − 1.97 | 0.90 | − 3.93 | -0.43 | − 0.87 | 0.52 | − 2.06 | − 0.08 |

| Follower | Industry | 2.76 | 1.14 | 0.78 | 5.17 | 1.74 | 0.93 | 0.12 | 3.70 |

| Good citizen | 4.07 | 1.48 | 1.52 | 7.29 | 2.25 | 1.36 | − 0.22 | 5.03 | |

| Incompetence | 0.32 | 0.49 | − 0.55 | 1.44 | 0.19 | 0.32 | − 0.31 | 0.98 | |

Note. Race was dummy coded with White Americans as the reference group, i.e., D1: Asian American with “American” first name = 1, White American = 0; D2: Asian American with Asian first name = 1, White American = 0. Bootstrap sample size = 5000. Coefficients in boldface indicate significant mediation

In Hypothesis 7, we predicted that, compared to the Asian American employee with the Asian first name, the Asian American employee with the “American” first name will be rated higher on ideal leader traits and lower on ideal follower traits, thereby leading to higher ratings on leadership potential. Our results do not support this hypothesis as both Asian American employees were rated similarly across most leader and follower traits as well as on leadership potential.

Discussion

In Study 3, we found some evidence of differences in perceptions of Asian American and White American non-managerial employees. However, surprisingly, the differences uncovered generally indicated a potential Asian leadership advantage relative to majority group employees. In other words, the Asian American employee was perceived as more promotable to a leadership role than the White American employee, in contrast to prior research that has generally found evidence that Asian Americans are disadvantaged when it comes to leadership.

Furthermore, the favorable perceptions of the Asian American employee were due to higher activation of ideal follower traits; specifically, industry and good citizen. This lends additional credence to our arguments that follower characteristics are likely to have important implications for leadership outcomes. However, we originally predicted that perceptions of fit with ideal follower traits would harm Asian Americans by pigeonholing them in subordinate roles. Our results point to the opposite effect; these characteristics may help Asian American workers to be viewed as employees who are likely to succeed in more senior roles with greater responsibility (Dries et al., 2012).

Finally, we note that tyranny was also a significant mediator, and perceptions that the Asian American employee was a poorer fit with this agentic leader trait compared to the White American employee decreased perceptions of the Asian American employee’s leadership potential. However, this negative effect, which is in line with prior findings and explanations regarding the Asian-White leadership gap (e.g., Sy et al., 2010), was not strong enough to overshadow the other followership-based mechanisms contributing to an Asian leadership advantage.5

We also note that our results around tyranny suggest the presence of suppression. Whereas tyranny was negatively associated with leadership potential in the zero-order correlations (r = − .16), it was positively related to leadership potential in the mediation model (b = 0.11) where it served as a mediator alongside the follower traits of industry and good citizen. As these follower traits include conceptions of effort and persistence, they may have been controlling for the aspects of tyranny that also require these characteristics, such as trying to manipulate and change others’ views. As a result, what remained in the dimension of tyranny may have been the dominance-related aspects of the construct. Because agency is viewed as critical for effective leadership (e.g., Eagly & Karau, 2002; Festekjian et al., 2014; Sy et al., 2010), the agentic aspects of tyranny may have created the positive relationship between tyranny and leadership potential.

Study 4: Exploring the Moderating Role of Threat

Study 2 uncovered little evidence of differences in observers’ perceptions of Asian American and White American managers, whereas Study 3 generated some evidence that Asian American workers may be advantaged over White American workers as they are seen as having greater leadership potential. Although Study 3 found evidence that Asian Americans may be advantaged for leadership positions primarily due to perceptions that they are diligent and loyal followers, the broader context whereby Asian Americans continue to be underrepresented in these roles suggests that these effects may be constrained to particular circumstances.

Thus, in this study, we sought to provide more insight and nuance regarding when these effects are more versus less likely to occur. Specifically, drawing upon social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), we argue that an important contextual factor is threat, as past studies have found that bias against Asian Americans occurs when observers feel threatened by the high-achieving qualities of the Asian minority group (e.g., Butz & Yogeeswaran, 2011; Ho & Jackson, 2001; Lin et al., 2005). In other words, although others may admire the high achievements and strong work ethic of this “model minority,” they can also feel envious and threatened by Asian Americans (Ho & Jackson, 2001). This is because Asian Americans may pose a threat for finite resources, such as limited leadership positions in the workplace. As a result, feelings of threat may motivate evaluators to be biased against this minority group (e.g., say they are unworthy of leadership positions) by invoking negative stereotypes about Asian Americans (e.g., Asian Americans are cold and antisocial; Lin et al., 2005) or by suppressing positive stereotypes about Asian Americans (e.g., Asian Americans are not hardworking and team players).

Said otherwise, because the paradigms we employed in our prior studies did not “cost” participants anything in their selection ratings or decisions (i.e., in Study 2 and 3, they were asked to rate a worker in a fictional organization), we may not have elicited the feelings of threat that are likely to occur when a highly qualified minority group member may attain a position higher than one’s own. Accordingly, participants may not have been motivated to derogate Asian American workers’ fitness for these roles or deny them these leadership opportunities. To address this possibility, in this study we conduct a 2 × 2 experiment to examine whether participants evaluate Asian American versus White American co-workers differently under conditions of threat or competition for a desired leadership role versus no threat.

Method

Participants

Participants from the U.S. were recruited from Prolific, a platform that connects potential participants with researchers (Palan & Schitter, 2018; Peer et al., 2017). We removed potentially problematic or careless respondents using the same criteria as Study 2 and 3 (n = 47).6 Additionally, after excluding participants who did not complete both phases of the study (n = 63), the final sample size was 390. Participants were compensated 1.25 GBP for each phase of the study. The majority (n = 231) of participants were male (59%), 158 (41%) were female, and 1 (0.3%) was undisclosed. Among participants, 309 (79%) self-identified as White, 14 (4%) as Black, 19 (5%) as Hispanic or Latino, 28 (7%) as East/Southeast Asian, and 20 (5%) as other or more than one ethnicity. The mean age of participants was 35 years (SD = 9 years). On average, participants had 14 years (SD = 10 years) of work experience.

Procedure

This study consisted of two phases. The first phase utilized a between-participants experimental design. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: White American co-worker and threat (n = 100), White American co-worker and no threat (n = 96), Asian American co-worker and threat (n = 96), Asian American co-worker and no threat (n = 98). After consenting to the study, participants read a vignette and were asked to imagine that they had a male co-worker (i.e., John Davis or David Wong) who was either being considered for a leadership role the participant was or was not interested in (i.e., threat versus no threat; see Supplementary Online Materials for full vignettes). Participants then rated this co-worker on leadership potential and standing on ideal leader and ideal follower traits. Approximately one week later, participants were invited to complete the second phase of the study that included exploratory measures and demographic information (e.g., participant race).7

The vignette was adapted from Study 3 materials, and we pilot-tested the threat manipulation in a separate sample of 101 U.S. participants who were recruited from Prolific. These participants were compensated 0.65 GBP. After excluding participants who failed attention checks (n = 5), the final sample size was 96. Participants were randomly assigned to either the threat (n = 48) or no threat (n = 48) condition. The vignette used in the pilot study differed from that in the main study in that it describes the co-worker in question generically (i.e., without reference to race or gender). Participants then rated how threatening they felt this co-worker to be using a 5-point Likert scale (3 items; “How threatened do you feel by your colleague?”, “To what extent do you feel that your colleague is your rival?”, and “To what extent do you feel that your colleague is hoarding valuable resources?”; α = .84), as well as their feelings of anxiety using a 7-point Likert scale (6 items; e.g., “tense”; α = .94; Butz & Yogeeswaran, 2011). Supporting the efficacy of the manipulation, participants in the threat condition reported perceiving their co-worker as significantly more threatening (M = 2.79, SD = 0.85) than participants in the no threat condition (M = 1.61, SD = 0.84), t(94) = − 6.85, p < .001. Furthermore, participants in the threat condition reported significantly greater anxiety (M = 4.07, SD = 1.47) than participants in the no threat condition (M = 2.56, SD = 1.38), t(94) = − 5.17, p < .001.

Measures

For Phase 1, we used the same measures, response scales, and instructions as in Study 3. Measures were generally highly reliable: leadership potential (α = .95), ILT traits (dynamism α = .93; tyranny α = .93; masculinity α = .548), and IFT traits (industry α = .97; good citizen α = .95; incompetent α = .93).

Covariates

All analyses controlled for participant race which was dummy coded (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic, and Other), with Asian as the reference group.

Results

Before testing our hypotheses, we again first tested for the presence of CMV. Although there was some evidence of CMV, follow-up analyses following the processes specified by Williams and McGonagle (2016) indicated that it did not affect or bias substantive relationships among study variables. Therefore, we moved forward to test study hypotheses (additional details can be found in the Supplementary Online Materials).

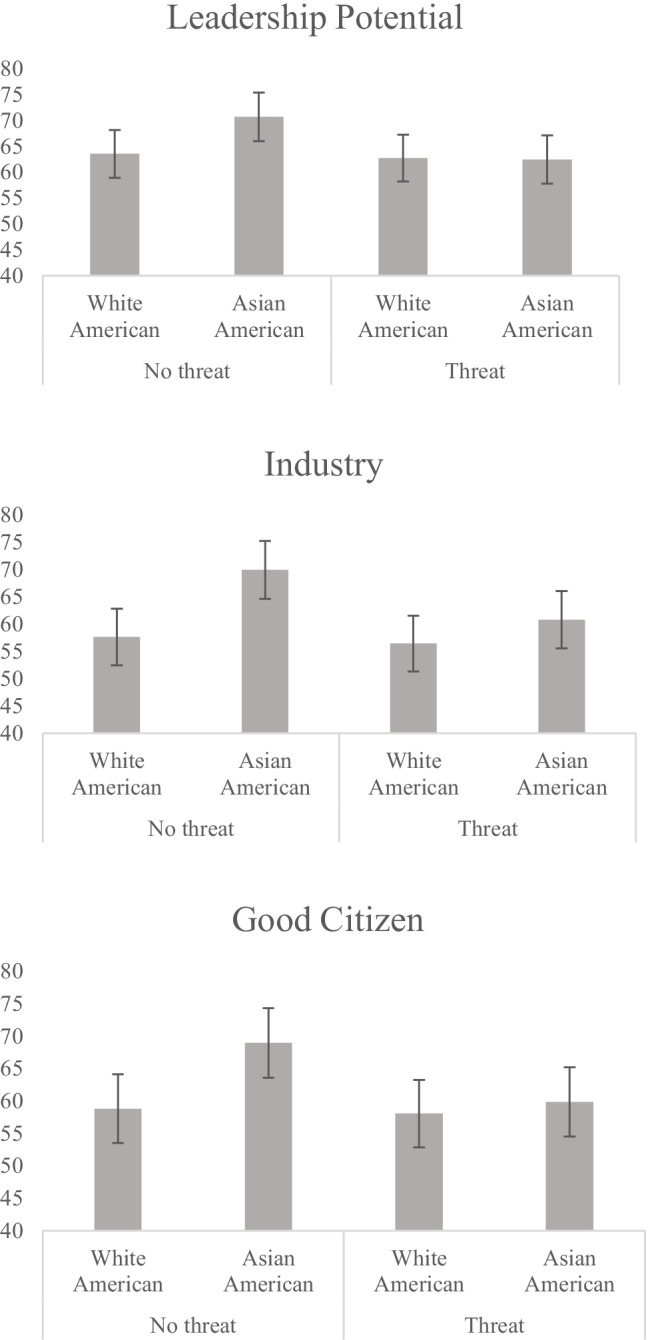

We examined whether the relationship between co-worker race and evaluations of leadership potential would vary by threat condition. Multiple regression analyses revealed a significant effect of co-worker race (b = 7.16, SE = 2.23, p = .001; see Table 9), such that the Asian American co-worker was generally rated as higher in leadership potential compared to the White American co-worker, similar to Study 3. Although there was no main effect of threat condition (b = − 0.79, SE = 2.23, p = .722), there was a significant race × threat interaction (b = − 7.47, SE = 3.17, p = .019) on ratings of leadership potential. Specifically, follow-up simple slope analyses revealed that the Asian American co-worker was rated as higher in leadership potential compared to the White American co-worker only when one was not in competition for the leadership role (b = 7.16, t = 3.21, p = .001), whereas this difference became non-significant when one was in competition with the co-worker for a leadership role (b = − 0.31, t = − 0.14, p = .892; see Fig. 3).

Table 9.

Study 4: Leadership potential, leader traits, and follower traits regressed onto race, threat, and race × threat interaction term

| Variable | Leadership potential | Leader | Follower | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamism | Tyranny | Masculinity | Industry | Good citizen | Incompetence | ||

| Black | − 1.50 (5.14) | − 1.49 (5.81) | − 5.92 (6.38) | 3.49 (5.70) | − 8.39 (5.81) | − 5.91 (5.90) | − 4.34 (6.47) |

| Hispanic | − 3.54 (4.63) | − 9.05 (5.22) | 0.49 (5.74) | − 1.44 (5.12) | − 6.28 (5.23) | − 7.38 (5.30) | 3.08 (5.82) |

| White | − 1.39 (3.07) | − 3.96 (3.46) | − 0.30 (3.81) | − 5.76 (3.40) | − 3.79 (3.47) | − 3.73 (3.52) | 2.54 (3.86) |

| Other | − 2.40 (4.56) | − 4.61 (5.15) | 7.24 (5.66) | − 3.69 (5.05) | − 3.68 (5.15) | − 5.06 (5.23) | 2.19 (5.74) |

| Race | 7.16 (2.23)** | 4.43 (2.52) | − 11.86 (2.77)*** | − 1.51 (2.47) | 12.31 (2.52)*** | 10.15 (2.56)*** | − 4.88 (2.81) |