Introduction

Pseudallescheria boydii is increasingly recognized as a source of infection in the immunocompromised. It has rarely been reported as a pathogen in immunocompetent patients, especially as a single cutaneous abscess. We present the case of a solitary P boydii abscess presenting in an immunocompetent man.

Case report

A 51-year–old man presented to the Columbia University Irving Medical Center in January 2021 for evaluation of an abscess on his right forearm. One year before presentation, he had cut his forearm while cleaning a broken fluorescent light bulb. The lacerated area initially healed without cause for concern, but over the following 6 months, the patient noticed that the affected area beneath the involved area began to swell, elicit pain when palpated, and express purulent discharge. In January 2021, he visited a local dermatologist, who cultured the abscess, revealing P boydii species complex. He was then referred to the Columbia University Irving Medical Center for further evaluation.

On presentation 3 weeks later, the patient reported that the nodule on his right forearm had continued to increase in size and express pus. The patient was a healthy male without a significant past medical history, including immunosuppressive conditions, and was not taking any immunosuppressive medications. He also denied a history of unusual environmental exposures, intravenous drug use, or recurrent infections. He denied fever, chills, night sweats, or recent weight loss; a complete metabolic panel and a complete blood cell count with differential were within normal limits. HIV qualitative polymerase chain reaction testing was negative.

Palpation of the right forearm revealed a 3.5 cm × 3.5 cm indurated nodule with central ulceration and purulent discharge (Fig 1, A and B). No other lesions were observed, and no lymphadenopathy was detected on examination. Wound cultures of the lesion grew P boydii species complex.

Fig 1.

A, Clinical photograph of the indurated pustular nodule with a central, crusted ulcer. B, Closer view of the same image.

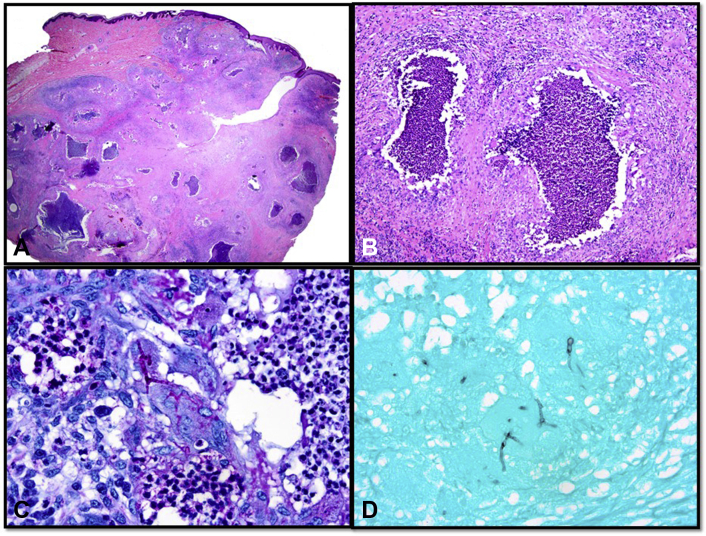

Excisional biopsy of the lesion on hematoxylin-eosin–stained histologic sections revealed a predominantly dermal-based nodule (Fig 2, A) composed of multifocal collections of neutrophils (Fig 2, B) surrounded by epithelioid and multinucleated histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Periodic acid–Schiff (Fig 2, C) and Gomori methenamine silver (Fig 2, D) stains showed several septate fungal hyphae with acute angle branching, resembling Aspergillus spp. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was negative for acid-fast bacilli.

Fig 2.

Histologic section of the biopsy specimen showing (A) a mostly dermal-based nodule (hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: ×10.25) composed of (B) multifocal neutrophilic aggregates and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate (hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: ×100). (C) Periodic acid–Schiff and (D) Gomori methenamine silver stains show septate fungal hyphae with acute angle branching (original magnification: ×400).

The patient was treated with wide local excision of the abscess and prescribed voriconazole 300 mg twice a day. The patient delayed initiation of voriconazole for 2 months, during which time small papules developed along the scar that were concerning for recurrent infection. He subsequently completed 3 months of voriconazole therapy. At the time of last follow-up, the area had healed well and showed no signs of recurrent infection (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Clinical photograph of the affected area after 3 months of voriconazole therapy with only residual scarring at the site of the prior excision.

Discussion

P boydii is a ubiquitous saprobic fungus known to grow in saltwater, sewage, soil, swamps, coastal tidelands, poultry manure, cattle manure, and bat feces.1 P boydii thrives in environments high in agricultural and industrial pollution, as the species is able to use nitrogen-containing compounds, such as fertilizers, and aromatic hydrocarbons found in oil and gas as nutrient sources.2 P boydii is the name of the teleomorph, or sexual state, of the fungal species, and Scedosporium apiospermum describes its anamorph, or asexual state.1,2 Although the names are interchangeable, P boydii commonly takes precedence in clinical descriptions.

P boydii is an opportunistic pathogen, responsible for a wide variety of clinical presentations. P boydii has become an increasingly recognized source of life-threatening infections in immunocompromised hosts with a high risk of progressing to disseminated disease.1 Cases of septic arthritis, endocarditis, and meningoencephalitis, among many other infectious complications, have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.1 Infection in immunocompetent patients is rare. The classic pathology attributed to P boydii in immunocompetent patients is mycetoma, a chronic, granulomatous infection of subcutaneous tissues and contiguous bone characterized by suppurative sinus tracts and expression of fungal “grains” representing organized mycelial aggregates.3,4 Pneumonia, bone and joint infections, otitis media, otitis externa, keratitis, endophthalmitis, and brain abscesses have also been reported in immunocompetent patients.1,5 Primary cutaneous infections in immunocompetent patients have been infrequently reported in the literature. A literature review of existing cases is presented in Table I.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In the currently reported case, the infection was isolated to a single abscess on the forearm of an immunocompetent host, which lacked the typical grains seen in P boydii mycetoma.

Table I.

Primary Cutaneous Presentations of Pboydii in Immunocompetent Patients

| Age/Sex | Clinical Diagnosis | Immune Status | Clinical Features | Microbiologic Diagnosis | Therapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 M | Pboydii mycetoma with co-occurring Madurella grisea mycetoma | No significant past medical history Normal CBC with differential Normal immunoglobulin levels Normal CD4, CD8 cell counts HIV negative |

8 cm × 5 cm firm, nonfluctuant, nontender nodule on right anterolateral ankle for months (exact number unknown) 6 cm × 5 cm nontender nodule on dorsal aspect of right hand for 8-10 mo |

Ankle lesion: Pboydii/Scedosporium apiospermum complex (S. apiospermum sensu stricto) Hand lesion: Madurella grisea |

Voriconazole (dosing not provided) for 6 mo | Complete resolution of the Scedosporium ankle lesion; minimal improvement of Madurella hand lesion |

| 25 F | Scedosporium apiospermum lymphadenitis | No significant past medical history Normal CBC with differential Normal lymphocyte subsets (T cells, B cells, and NK cells) Normal immunoglobulin and complement levels Normal phagocytic activity and burst activity of neutrophils and monocytes |

Mobile and nontender lymph nodes (0.5-2 cm) in the anterior and posterior cervical chains for 10 y; posttraumatic scar on right hemiface secondary to laceration 12 y prior | Scedosporium apiospermum | Itraconazole, 200 mg 3 times daily for 1 y | Complete resolution after 1 y |

| 73 F | Pangusta soft tissue infection | No significant past medical history Additional labs not reported |

Multiple painful 1- to 3-mm erythematous papulopustules on the dorsum of the left hand for 4 mo | Pangusta | Oral itraconazole 200 mg/day for 4 wk with transition to oral voriconazole 400 mg/day for 3 mo | Slight improvement after oral itraconazole Complete resolution after 3 mo of oral voriconazole |

| 16 M | Multiple subcutaneous mycetomas | No significant past medical history CBC with mild anemia, mild leukocytosis (WBC 13), and mild eosinophilia Normal bone marrow aspirate |

Numerous subcutaneous nodules involving the neck, trunk, arms, and thighs ranging from 2 to 15 cm for 8 y | Pboydii/Scedosporium apiospermum complex (no speciation reported) | Initially treated with oral itraconazole with periodic needle aspirations for 4 wk Switched to potassium iodide saturated solution 1 mL 3 times a day, subsequently increased to 6 mL each dose due to financial difficulties |

Complete resolution of lesions after 2 y |

| 58 M | Pboydii/Scedosporium apiospermum species complex and Neisseria spp. soft tissue infection of the forearm | No significant past medical history Normal CBC |

Numerous pustules and woody induration of left forearm for 5 y following dog bite |

Pboydii/Scedosporium apiospermum complex Neisseria spp. |

Oral voriconazole 200 mg twice daily for 6 mo Amoxicillin/clavulanate for 6 wk |

Significant improvement after 6 mo |

CBC, Complete blood cell count; NK, natural killer; WBC, white blood cell.

P boydii infection requires extended treatment, with some patients requiring years of antifungal therapy due to frequent recurrence. Recent DNA studies have shown that P boydii is likely not a single species but rather a “species complex” including at least 6 known species (P boydii, P angusta, P ellipsoidea, P fusoidea, P minutispora, and Scedosporium aurantiacum) and 2 recently reported species (P minutispora and S aurantiacum).11,12 This phylogenetic diversity may explain the difficulty in treating these infections. Gilgado et al11 tested 84 isolates belonging to 8 species that constitute the P boydii species complex against 11 antifungal agents. Among the antifungal agents tested, voriconazole had a fungicidal effect in the most species.11 A long course (at least 3 months) is usually required due to the recalcitrant nature of the infection.

This report highlights a rare case in which P boydii presented as a solitary abscess on the right forearm of an immunocompetent man. This underscores the need to maintain a broad differential diagnosis and to include deep fungal infections in the assessment of nodules associated with transcutaneous trauma. In addition to a routine workup, including biopsy and bacterial cultures, fungal cultures should always be considered. Sensitivity testing is important, as P boydii may be resistant to numerous antifungal agents due to the organismal diversity of the P species complex. Treatment requires aggressive management with debridement and long-term antifungal therapy.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Cortez K.J., Roilides E., Quiroz-Telles F., et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(1):157–197. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guarro J., Kantarcioglu A.S., Horré R., et al. Scedosporium apiospermum: changing clinical spectrum of a therapy-refractory opportunist. Med Mycol. 2006;44(4):295–327. doi: 10.1080/13693780600752507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichon V., Khachemoune A. Mycetoma : a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(5):315–321. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horré R., Schumacher G., Marklein G., et al. Mycetoma due to Pseudallescheria boydii and co-isolation of Nocardia abscessus in a patient injured in road accident. Med Mycol. 2002;40(5):525–527. doi: 10.1080/mmy.40.5.525.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhally H.S., Shields C., Lin S.Y., Merz W.G. Otitis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in an immunocompetent child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68(7):975–978. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulati V., Bakare S., Tibrewal S., Ismail N., Sayani J., Baghla D.P.S. A rare presentation of concurrent Scedosporium apiospermum and Madurella grisea eumycetoma in an immunocompetent host. Case Rep Pathol. 2012;2012:154201. doi: 10.1155/2012/154201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiraz N., Gülbas Z., Akgün Y., Ö Uzun. Lymphadenitis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(3):e59–e61. doi: 10.1086/318484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi H., Kim Y.I., Na C.H., Kim M.S., Shin B.S. Primary cutaneous Pseudallescheria angusta infection successfully treated with voriconazole in an immunocompetent patient. J Dermatol. 2019;46(11):e420–e421. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan F.A., Hashmi S., Sarwari A.R. Multiple subcutaneous mycetomas caused by Pseudallescheria boydii: response to therapy with oral potassium iodide solution. J Infect. 2010;60(2):178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kollu V.S., Auerbach J., Ritter A.S. Soft tissue infection of the forearm with Scedosporium apiospermum complex and Neisseria spp. following a dog bite. Cureus. 2021;13(3) doi: 10.7759/cureus.14140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilgado F., Serena C., Cano J., Gené J., Guarro J. Antifungal susceptibilities of the species of the Pseudallescheria boydii complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(12):4211–4213. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00981-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilgado F., Cano J., Gené J., Guarro J. Molecular phylogeny of the Pseudallescheria. boydii species complex: proposal of two new species. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(10):4930–4942. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.4930-4942.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]