Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae has emerged as the leading liver abscess pathogen in Taiwan, with the percentage rising from 30% in the 1980s to over 80% in the 1990s. Most of the patients with K. pneumoniae liver abscess are diabetic and without biliary tract disease. Some patients develop serious extrahepatic complications such as endophthalmitis, meningitis, lung abscess, and necrotizing fasciitis. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was used for cluster analysis of 96 isolates from patients with liver abscess and 60 isolates from patients with other diseases. A total of 136 PFGE types were identified. Among the 96 liver abscess-associated isolates, 60 (62.5%) were classified in major cluster A. Cluster A included 41 PFGE types (types 1 to 41) which had a genetic similarity of at least 72.4% ± 9.4%. The PFGE patterns of cluster A strains are so similar that they could have originated from the same ancestor. This study demonstrates that cluster A plays an important role in the high incidence of K. pneumoniae liver abscess in Taiwan.

Bacterial liver abscess is usually a complication of biliary tract disease (30 to 35%), contiguous infections such as subphrenic abscess or empyema of the gallbladder (15%), and intestinal diseases (15%) (3). Escherichia coli is the most common liver abscess pathogen, with a percentage of about 35 to 45% worldwide (3, 6). However, these trends have changed in Taiwan. Klebsiella pneumoniae has emerged as the leading liver abscess pathogen in Taiwan, with the percentage rising from 30% in the 1980s to over 80% in the 1990s (10, 11). Most of the patients with K. pneumoniae liver abscess are diabetic and without biliary tract disease (10). Some patients develop serious extrahepatic complications such as endophthalmitis, meningitis, lung abscess, and necrotizing fasciitis (1, 4, 10). Although K. pneumoniae liver abscess has become an endemic disease in Taiwan in the past 2 decades (1, 10), there is still no national surveillance of this disease and the annual incidence is not exactly known. About 40 patients with K. pneumoniae liver abscess are admitted annually to Taichung Veterans General Hospital, which is a 1,000-bed medical center located in central Taiwan. Estimates suggest that the annual incidence will be over 200 cases islandwide. All of the K. pneumoniae strains from liver abscesses remain susceptible to quinolones, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, aminoglycosides, and all β-lactam antibiotics except ampicillin and ticarcillin by the disk diffusion tests (1, 10). Because these K. pneumoniae isolates just have emerged within 2 decades and have many similar clinical characteristics, they could be clonal in the population structure. In this study, we found a major cluster of genetically related K. pneumoniae isolates from liver abscess patients by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

A total of 156 K. pneumoniae isolates (96 isolates from liver abscess patients, 60 isolates from patients with other diseases) were analyzed. Of the 96 liver abscess-associated isolates, 79 (isolates 1 to 79) were collected from Taichung Veterans General Hospital (TCVGH) between February 1994 and December 1997 and 17 isolates (isolates 80 to 96) were provided by Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital (CGMH), located in northern Taiwan, between December 1987 and October 1989. Sixty isolates (isolates 97 to 156) from patients with other diseases were collected from six hospitals around Taiwan. The sources included blood (26.7%), sputum (30%), urine (28.3%), and wounds (15%). All of the isolates were collected from different patients, except isolates 30 and 31, which were recovered from the same patient during different liver abscess episodes. The date and source of isolation, underlying diseases, and associated complications were obtained from the chart records.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared as described previously (8). The DNA blocks were digested with 30 U of XbaI at 37°C for 2 h. Restriction fragments of DNA were separated by PFGE with a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) through 1.2% SeaKem GTG agarose gel (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine). The fragmented DNA was run at a field strength of 6 V/cm for 24 h at 14°C, and the pulse time was increased from 5 to 40 s. A lambda ladder (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used as the molecular size marker. The genetic relatedness between any two isolates was estimated by calculation of the Dice coefficient of similarity as follows: 2 × number of matching bands/total number of bands in both strains. Isolates were considered to be within a cluster if the range of relatedness was >0.80. The PFGE patterns were analyzed by Windows version 3.1b of Gelcompar (Applied Math, Kortrijk, Belgium). A dendrogram was constructed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages using the Dice coefficient in accordance with the instructions of the Gelcompar manufacturer. A 1.5% band position tolerance was applied for comparison of PFGE fingerprinting patterns.

PFGE is usually a good method for analysis of potential outbreaks spanning relatively short periods (1 to 3 months) (9). However, PFGE usually resolves a limited number of fragments (about 10 to 20), so only relatively major genetic events (such as recombination, insertion, or deletion of a relatively large DNA fragment) can result in changes in fingerprinting patterns. PFGE patterns will remain unchanged if the genetic events are relatively minor, such as a point mutation or insertion or deletion of a relatively small DNA fragment not involved in the restriction site. Errors of calculation of genetic relatedness will appear when several genetic events have occurred over a relatively long period of time. Hence, calculation of genetic relatedness by comparison of restriction patterns cannot be totally reduced to algorithms (9). PFGE can be ambiguous, especially when a large number of strains are analyzed. The artificial band differences due to comparison of strains in distant lanes of the same gel or in different gels and poor resolution of smaller fragments will influence the reading of genetic relatedness. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST), based on the proven concepts of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, analyzes the clonal lineages by identifying alleles from the nucleotide sequences of internal fragments of housekeeping genes. MLST can overcome the ambiguity and has been validated for the identification of clusters of related isolates (clones) among a large number of strains over a long period of time (2, 5, 7). Considering the relatively longer time required to develop MLST results for K. pneumoniae, PFGE provides a simple overview of the population structure of K. pneumoniae to alert the medical community of a potential new threat to public health.

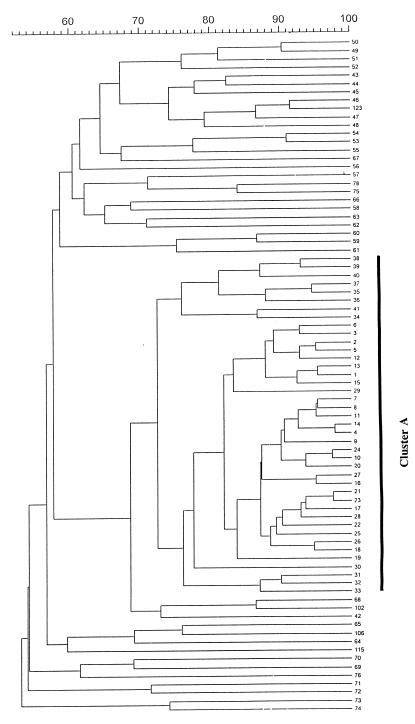

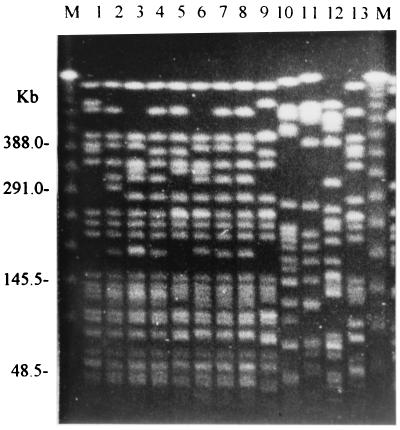

A total of 136 PFGE types were identified among 156 isolates. Types 1 to 76 were assigned to 96 liver abscess isolates, and types 77 to 136 were assigned to 60 isolates from patients with other diseases. The dendrogram of 76 PFGE types from liver abscess-associated isolates and 5 PFGE types (types 78, 102, 106, 115, and 123) from non-liver abscess isolates is shown in Fig. 1. Sixty isolates (62.5% of all liver abscess isolates) were classified as belonging to a major cluster (cluster A). Cluster A included 41 types (types 1 to 41) with a genetic similarity of at least 72.4% ± 9.4%. The PFGE patterns of the cluster A isolates were so similar that they could have originated from the same ancestor. Ten isolates, which were recovered from TCVGH over a period of 3 years, had the same PFGE pattern, type 1. The other 36 liver abscess isolates had less than 68.5% ± 7.0% similarity to cluster A, so they are genetically unrelated to cluster A. Six minor non-A clusters (types 49 to 51, 43 and 44, 46 and 47, 53 and 54, 59 and 60, and 67, respectively) were identified among liver abscess-associated isolates. There was only one isolate for each type of the above minor clusters, but two isolates were identified as type 67. Although the isolates of these clusters are possibly related genetically, no epidemiological link was found. Among the isolates from diseases other than liver abscess, type 102 isolates were most similar to those in cluster A (a similarity of 68.5% ± 7.0%) (data not shown). Hence, cluster A isolates were unrelated to the non-liver abscess isolates. This indicates that cluster A isolates are not the most abundant in the normal population of K. pneumoniae. Most of the non-liver abscess isolates were unrelated to liver abscess-associated isolates, but 3 of 60 non-liver abscess isolates (types 78, 102, and 123) had a similarity of >80% to non-cluster A liver abscess isolates (types 75, 68, and 46, respectively). Ten isolates from CGMH has a similarity of >75.9% ± 8.7% and were classified as belonging to types 35 to 41 in cluster A. The other seven isolates from CGMH were assigned to the non-cluster A group. PFGE fingerprinting of 13 isolates is shown in Fig. 2 to emphasize the similarity of cluster A to non-cluster A strains. A summary of PFGE clusters and clinical data is shown in Table 1. Fifty-four (56.8%) of 95 patients had diabetes mellitus. Nine (9.5%) patients developed extrahepatic infections. All of the isolates that cause metastatic infections (including endophthalmitis, lung abscess, pleural empyema, renal abscess, pancreatic abscess, and necrotizing fasciitis) belonged to cluster A, except isolates 16 and 51 (types 53 and 52, respectively).

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram illustrating the relatedness of 81 PFGE types. The numbers on the right are the PFGE types. The scale measures similarity values. Cluster A included 41 PFGE types (types 1 to 41) which had a genetic similarity of at least 72.4% ± 9.4%. Types 78, 102, 106, 115, and 123 are shown to emphasize that non-liver abscess isolates were unrelated to cluster A.

FIG. 2.

PFGE fingerprinting of 13 K. pneumoniae isolates digested with XbaI. The lane numbers indicate the isolate numbers. Lane M contained a lambda ladder (Bio-Rad) that served as a molecular size marker.

TABLE 1.

PFGE clusters and clinical data of K. pneumoniae isolates from patients with liver abscess and other diseases

| Cluster | Isolation dates | No. of isolates | PFGE types | % of patients with:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMa | Metastatic focus | ||||

| Liver abscess | |||||

| A | 1989–1997 | 60 | 1–41 | 50.8 | 11.9 |

| Non-A | 1989–1997 | 36 | 42–76 | 66.7 | 5.6 |

| Subtotal | 96 | 1–76 | 56.8 | 9.5 | |

| Other diseases | 1993–1998 | 60 | 77–136 | Unknown | Unknown |

DM, diabetes mellitus.

Isolates 30 and 31 (type 2) were recovered from the same patient during two different liver abscess episodes 2 years and 4 months apart. Type 67 included isolates 21 (from TCVGH) and 87 (from CGMH), which were collected 5 years apart. Type 1 included 10 isolates that were collected between March 1994 and July 1997. There is no data showing how fast K. pneumoniae evolves to change the PFGE patterns. The PFGE patterns seem to be relatively conserved within a short period of 2 to 5 years, so the genetic diversity among strains of cluster A could have evolved over the past 2 decades. Due to the limited regions of isolation and number of isolates, sampling bias was possible. However, Taiwan is a relatively small island, with an area of only 35,574 km2, and convenient transportation of foods and the human population could facilitate the spread of pathogens and reduce the problem of sampling bias. Therefore, we could still see isolates from different geographic areas that were classified as a cluster, for example, minor clusters, including types 49 (from TCVGH) and 50 (from CGMH), 53 (from TCVGH) and 54 (from CGMH), and 67 (from TCVGH and CGMH), and major cluster A, including types 1 to 34 (from TCVGH) and 35 to 41 (from CGMH).

Thirty-six isolates (types 42 to 76) were distinctively different from cluster A. Why was such a high level of genetic diversity observed among these strains? There are a few possibilities. First, cluster A strains may somehow be the most abundant in the normal population of K. pneumoniae, rather than the specific pathogenic clone for liver abscess. However, this is not compatible with the fact that cluster A isolates were not found in diseases other than liver abscess. Hence, the high incidence of cluster A in liver abscess is not coincidental. Second, any genetically unrelated K. pneumoniae strains could have the same ability to cause liver abscess. However, the clinical observations refute this possibility. K. pneumoniae is also a common nosocomial pathogen of biliary tract infection and bacteremia, but these nosocomial strains rarely cause liver abscess. Furthermore, such a high incidence of liver abscess caused by K. pneumoniae has never been reported in other countries. Third, it is possible that cluster A isolates originated from the same ancestor and have the same virulence factors that cause liver abscess. These genetically unrelated strains could acquire the virulence factors from cluster A strains via horizontal genetic transfer, such as chromosomal recombination or plasmid transfer. Further studies are necessary to establish the pathogenesis of liver abscess. Fourth, PFGE usually resolves the genetic variation that is evolving very rapidly and may be too discriminatory to identify the lineages for long-term epidemiology (5). Therefore, these non-cluster A strains with unrelated PFGE patterns could have originated from the same ancestor and changed their ancestral PFGE patterns after several genetic events over the last 2 decades but still maintained the virulence factors. MLST identifies the genetic variation, which is selectively neutral and is evolving slowly, so further study by MLST could be more appropriate for identification of the clonal lineage of K. pneumoniae.

This study demonstrates that cluster A plays an important role in the high incidence of liver abscess in Taiwan. However, the route of transmission of the pathogenic clones of K. pneumoniae is still unknown. Cross infection of liver abscess within families and hospitals is very rare. This does not mean that K. pneumoniae will not spread through close contact. It is possible that people carry the pathogenic K. pneumoniae strains and spread the strains to others rather than develop liver abscesses. Our concern is that this endemic clone may spread to other countries. Further studies on the pathogenesis and mode of transmission are required to control the spread of these pathogenic K. pneumoniae strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank the microbiology laboratory staff for the collection of strains and Su-Feng Lee for the storage of strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheng D L, Liu Y-C, Yen M-Y, Liu C-Y, Wang R-S. Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess. Their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1557–1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enright M, Spratt B G. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology. 1998;144:3049–3060. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frey C F, Zhu Y, Suzuki M, Isaji S. Liver abscesses. Surg Clin N Am. 1989;69:259–271. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y-C, Cheng D-L, Lin C-L. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess associated with septic endophthalmitis. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:1913–1916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maiden M C J, Bygraves J A, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell J E, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant D A, Feavers I M, Achtman M, Spratt B G. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seeto R K, Rockey D C. Pyogenic liver abscess: change in etiology, management, and outcome. Medicine. 1996;75:99–113. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Z-Y, Enright M, Wilkinson P, Griffiths D, Spratt B G. Identification of three major clones of multiply antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Taiwanese hospitals by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3514–3519. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3514-3519.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Z-Y, Liu P Y-F, Lau Y-J, Lin Y-H, Hu B-S. Epidemiological typing of isolates from an outbreak of infection with multidrug-resistant Enterobacter cloacae by repetitive extragenic palindromic unit b1-primed PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2784–2790. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2784-2790.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J-S, Liu Y-C, Lee S S-J, Yen M Y, Chen Y-S, Wang J-H, Wann S-R, Lin Hsi-Hsun. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1434–1438. doi: 10.1086/516369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang C-C, Chen C-Y, Lin X-Z, Chang T-T, Shin J-S, Lin C-Y. Pyogenic liver abscess in Taiwan: emphasis on gas-forming liver abscess in diabetics. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1911–1915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]