Abstract

Introduction

Telehealth (TH) services rapidly expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic. This rapid deployment precluded the opportunity for initial planning of implementation strategies. The purpose of the quality improvement project was to understand the needs of nurse practitioners and examine TH procedures and interventions designed to promote high-quality, equitable health care for pediatric patients with gastrointestinal concerns.

Method

The Plan-Do-Study-Act model was used. Survey data from providers and families were collected and analyzed. They were further illuminated through iterative dialog across the research team to determine the quality and efficiency of TH.

Results

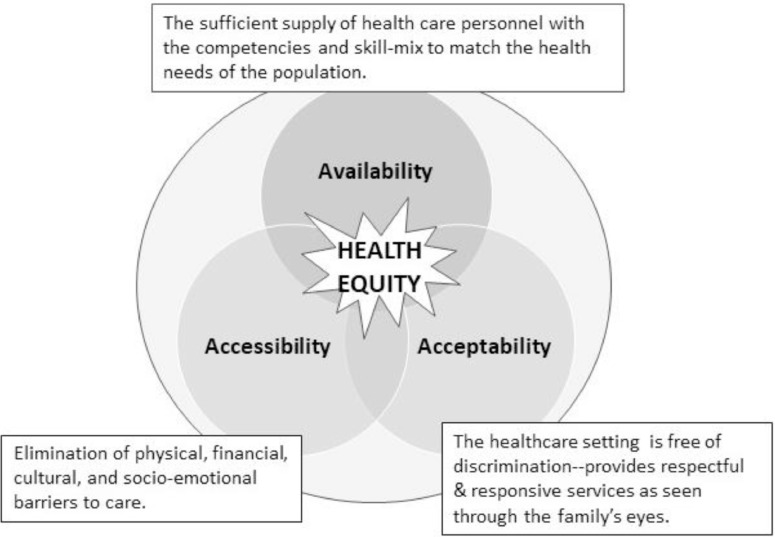

A toolkit of strategies for promoting the quality and efficiency of TH was created according to the three domains of health equity: availability, accessibility, and acceptability.

Discussion

TH will be used in the postpandemic era. Institutions need to implement evidence-based strategies that ensure health equity across TH platforms to ensure excellent patient care.

KEY WORDS: Telehealth, health equity, nurse practitioner, quality improvement, pediatrics

Although telehealth (TH) began in the late 1800s, these practices have grown exponentially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bestsennyy, Gilbert, Harris, & Rost, 2020; Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine, 2012). TH platforms and other digital health innovations present a viable option to efficiently and safely provide some forms of patient care (Crawford & Serhal, 2020), but widespread usage by many health care organizations was previously uncommon. Such was the case for one quaternary freestanding children's hospital in the northeast United States. The capacity of their pediatric clinics to see patients in-person was sharply curtailed during the COVID-19 pandemic when state-wide guidance and organizational decisions required that all nonemergent care be delivered electronically. The gastroenterology (GI) nurse practitioner (NP) team immediately shifted their clinical practices to TH, but its rapid deployment precluded the opportunity for initial planning and design of virtual clinic visits (Health IT.gov, 2017). Initially, parental anxieties surrounding their child's health and provider concerns on providing quality patient care were paramount. As a part of implementing robust TH practices, promoting health equity for all patients and families was of primary importance. It could not be assumed that every family had access to the necessary digital technologies or the wherewithal to meaningfully engage in TH. In addition, it could not be assumed that the GI NPs and larger health care systems were positioned to deliver care in this manner. Of particular concern to the team was how to provide high-quality care to their patients whose families were under-resourced or had low health literacy.

This quality improvement project (QIP) was designed to determine the feasibility and efficiency of TH visits for patients, parents, and providers. Emphasis was on assessing whether care was equitable for all families and, where barriers were identified, to determine how best to address them. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement's (n.d.) Plan-Do-Study-Act model for conducting quality initiatives provided the structure for designing and operationalizing this project. The revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0; SQUIRE, 2020) guidelines provide the systematic framework for reporting this project's findings (Ogrinc et al., 2016).

AVAILABLE KNOWLEDGE

Telehealth

TH takes many forms; for this, QIP TH refers to NP-patient/parent communication using live (synchronous) audio-video conferencing, or in the absence of video capability, audioconferencing. TH uses the electronic transmission of health care data to consult new patients, provide diagnoses, conduct follow-up visits, and recommend treatment plans (Crawford & Serhal, 2020; Olson, 2018). It was originally designed to increase access for basic acute care to select populations, including the military, prisons, and rural locations. As the digital divide has narrowed, varied clinical applications are now widely used across diverse populations and settings (Dorsey & Topol, 2016; Park, Erikson, Han, & Iyer, 2018). Patient enthusiasm for TH is much higher in younger populations, making it a popular care platform with unlimited potential for pediatric patients and their families (Park et al., 2018).

TH has distinct advantages. Health care providers can be more available to geographically diverse populations and allocate their time more efficiently to care for patients needing the most attention. TH also allows for greater multidisciplinary team involvement, creating a more patient-centric approach that is associated with improved patient outcomes (Kvedar, Coye, & Everett, 2014). Patients have generally reported high satisfaction with TH; it is convenient, reduces travel time and costs, and limits time away from their jobs (Kruse et al., 2017). During the pandemic, TH proved to enhance infection control by eliminating patients’ and families’ potential exposure to COVID-19 associated with onsite visits and conserve limited resources such as reducing the usage of personal protective equipment by hospital personal (Berg et al., 2020).

TH's major disadvantages for both the providers and the patients are a potentially less robust therapeutic relationship, inability to conduct a thorough physical examination, and incompatibility of available digital technologies (Dorsey & Topol, 2016). When a physical examination is needed, TH is not a preferred option as basic examination techniques—auscultation, palpation, and percussion—are not possible, and inspection is limited (Chaet, Clearfield, Sabin, Skimming, & Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs American Medical Association, 2017). Health care providers must convey precise instructions and rely on the patients to follow their directions for some examination techniques and interpret findings despite not knowing what is normal; when important information is not captured, it imposes risks that can lead to further problems such as missed or incorrect diagnoses. Incompatibility between institutional software and patient digital devices, difficulty establishing or maintaining an electronic connection, and breaches in privacy are also common issues (Alverson et al., 2008).

Many organizations, such as the American Medical Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and adult gastroenterology societies, have provided pediatric gastroenterology provider guidelines on implementing TH into their practice (Berg et al., 2020). However, across these guidelines was the failure to address specific considerations in conducting TH with under-resourced patients and families or those that have low levels of health or technological literacy.

Health Equity

Providing high-quality care requires that principles for achieving health equity are used in its planning and delivery. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020) defines health equity as “achieved when every person has the opportunity to attain his or her full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or other socially determined circumstances.” The three central domains of health equity are accessibility, availability, and acceptability (see Figure ). Health inequities are reflected in differences in length and quality of life, rates and severity of the disease, disability and death, and access to treatment. These will result in poor patient outcomes (Crawford & Serhal, 2020).

FIGURE.

Health equity framework

TH is generally viewed as an equalizer to providing care to diverse pediatric populations (Brophy, 2017; Utidjian & Abramson, 2016). However, TH creates specific health equity concerns for patients from families with fewer technological resources or poorer health literacy. Underserved populations have not historically used synchronous video communication as widely as other socioeconomic groups (Park et al., 2018). Providers must be prepared to address all aspects of the cultural, social, and economic barriers that come with TH.

Specific Site Information

The gastroenterology department schedules approximately 56,000 patients annually and has 11 clinic sites across eastern Massachusetts. The NPs are experts in managing GI issues, with an average of 15 years of experience working as advanced practitioners (range: 5–30). Their caseloads include patients from birth through young adulthood and span a wide array of acute and chronic conditions of varying levels of complexity. Most of these conditions are chronic; many are exacerbated by stress and require expensive treatments. Carefully tracking their clinical course and proactive management of emerging issues is critically important.

The pandemic created an environment that allowed the symptomology of many GI disorders to flourish, hindering patients’ health-related quality of life. Most patients seen in the GI Department are followed on a regular basis and have a long-term relationship with their NP. TH visits with their GI NP provided a lifeline for patients and families; without these visits and early intervention, patients would need to resort to seeking care in the emergency department with the potential for the hospital admission. The result would be a worsening clinical course, more expensive care, and, unfortunately, an increased risk of community or hospital exposure to COVID-19.

PROJECT RATIONALE AND SPECIFIC AIMS

Shortly after the rapid deployment of TH, NP anecdotal impressions supported that quality care for selected visit types could be rendered through TH, and these encounters are generally well-received by families. However, with a lack of objective data, it was not possible to clearly delineate strengths and weaknesses and thus limited the development of best practices for the use of TH across diverse populations. Specific aims of this QIP were as follows:

-

1.

determine variables important to quality telehealth interactions (NP experience, “known” patient, the reason for visit, the sophistication of telehealth platform, NP's comfort with technology, working relationship with the supervising attending);

-

2.

codify specific elements identified by NPs that impact the efficiency and effectiveness of TH interactions with families from diverse backgrounds;

-

3.

identify potential issues of health disparity when using TH as a primary method of health care delivery with children and their parents; and

-

4.

design a patient/family-centric toolkit for NP TH visits, with individual strategies appropriate for further testing.

METHODS

Context

A modified participatory action research (PAR) approach was adopted for this QIP. The PAR methodology addresses complex phenomena by intentionally engaging participants in sharing local knowledge while engaging them in obtaining relevant solutions for the community of interest (Fardi, Grunbaum, Gray, Franks, & Simoes, 2007; Jones, 2009). A specific goal of PAR is to improve health and reduce health inequities (Baum, MacDougall, & Smith, 2006). The team was composed of GI NPs (n = 4), a nurse scientist, nursing leadership (n = 2), and registered research nurses (n = 2). The team met weekly via Zoom (Zoom, 2020) to design, conduct, and evaluate this project. Every week, team members reflected on components of the TH rollout, adjusting their practices when possible. Each step is described later.

Plan

Joint Commission regulations and published evidence describing the use of TH with children with chronic/complex conditions were reviewed. Using this information and expert opinion, two data collection tools were designed for this project—the Provider GI TH Data form and the Parent/Patient GI TH Data form. Both instruments were adapted, incorporating new items specific to TH and GI care, from approved quality improvement forms already used by the hospital.

The Provider form contains six separate domains: (1) encounter characteristics (including International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, and current procedural terminology codes), (2) consultations, (3) electronic communication strategies employed, (4) visit complexity level, (5) call disposition, and (6) time involvement. Operational definitions for variables in each domain helped standardize data collection (Vessey, McCrave, Curro-Harrington, & DiFazio, 2015). The Parent/Patient form consisted of 10 Likert-style items specific to the patient experience and another three items comparing TH and onsite visit family-incurred costs; these items were adapted on the basis of published recommendations (Dávalos, French, Burdick, & Simmons, 2009; Henderson, Davis, Smith, & King, 2014). Iterative drafts of both instruments were trialed, evaluated, and modified; final drafts were formatted into REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), a secure web application for data management.

Do

Before data collection and in consultation with a statistician, it was determined a priori sample of 100 visits would provide sufficient descriptive data collected on the Provider GI TH Data form regarding the overall TH visit, and a sample size of 80 (two-sided 95% confidence interval with a width equal to 0.186 when the sample proportion was 0.800) would be adequate for the parent/patient survey. Before the initiation of data collection, the GI NPs trialed the Provider GI TH Data form to help ensure interrater reliability. Data were then collected on consecutive TH visits. The NP's recorded time spent on (1) preparing for the visit, (2) seeing the patient, (3) developing the management plan, (4) ordering medications and diagnostic tests, and (5) recording key information in the patient's electronic medical record. Finally, they recorded the TH platform used (e.g., Zoom [Zoom, 2020], SBR Health [SBR Health, 2020], Doximity [Doximity, 2020]) and the quality of the video and sound.

Parents/patients were asked at the visit's conclusion if they would be willing to be contacted regarding their TH experience by a research nurse. Families who agreed completed the Parent/Patient form over the phone within several days of the visit; data were later transcribed into REDCap. The GI NPs’ then forwarded their completed tool to the research nurses. The GI NPs engaged in regular, unstructured discussions with the full QIP team about the challenges or barriers they faced while providing care with TH over the prior week. Key information from these discussions was captured for later analysis.

Study

Data garnered from the Provider (n = 169) and Parent/Patient (n = 80) GI TH Data forms were downloaded from REDCap into SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated and are presented in Tables 1 and 2 . To better understand the socioeconomic composition of this sample and look for differences in TH patterns, median household income was estimated using zip code status (University of Michigan, Population Studies Center, Institute for Social Research, & Morenoff, 2011). In the sample captured in the Parent/Patient follow-up interviews, 38.8% had an estimated median household income below the 50th percentile for this New England catchment area. Finally, the weekly information collected from the GI NPs illuminated these findings. The data from these three sources were triangulated to help create relevant solutions for the community of interest.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of calls received

| Initial visit, n | Follow-up visit, n | Combined, n, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit information and management | |||

| Total visits | 75 | 94 | 169, 100 |

| Clinical management | 75 | 91 | 166, 98.22 |

| Patient education/anticipatory guidance | 74 | 86 | 160, 94.67 |

| Medication management/prescriptions | 46 | 39 | 85, 50.30 |

| Formula management/prescriptions | 8 | 6 | 14, 8.28 |

| Laboratory orders (in-house) | 23 | 14 | 37, 21.89 |

| Laboratory orders (external laboratory) | 4 | 2 | 6, 3.55 |

| Infusion orders | 0 | 1 | 1, 0.59 |

| Imaging orders and other procedures | 15 | 8 | 23, 13.61 |

| Scheduling follow-up appointments | 68 | 65 | 133, 78.70 |

| Getting outside medical records | 12 | 2 | 14, 8.28 |

| Ordering supplies/services | 0 | 1 | 1, 0.59 |

| Other | 2 | 3 | 5, 2.96 |

| Referrals | |||

| Nutritionist | 9 | 13 | 22, 13.02 |

| Feeding team | 3 | 5 | 8, 4.73 |

| Social services | 1 | 3 | 4, 2.37 |

| Mental health | 4 | 4 | 8, 4.73 |

| Other specialists | 5 | 4 | 9, 5.33 |

| Insurance coverage/payment | 0 | 1 | 1, 0.59 |

| Communicated with: | |||

| Administrative staff | 27 | 54 | 81, 47.93 |

| Gastroenterology nurse | 1 | 2 | 3, 1.78 |

| Gastroenterologist/other specialist | 24 | 30 | 54, 31.95 |

| Laboratory personnel | 1 | 1 | 2, 1.18 |

| Radiology personnel | 0 | 0 | 0, 0 |

| Social worker/psychologist | 5 | 8 | 13, 7.69 |

| Pharmacist | 2 | 4 | 6, 3.55 |

| Primary care provider | 9 | 4 | 13, 7.69 |

| Other | 2 | 6 | 8, 4.73 |

| Modes of communication used | |||

| SBR | 71 | 83 | 154, 91.12 |

| Zoom | 6 | 8 | 14, 8.28 |

| Telephone | 28 | 20 | 48, 28.4 |

| 63 | 52 | 115, 68.05 | |

| Patient portal | 0 | 2 | 2, 1.18 |

| Electronic medical record message center | 0 | 0 | 0, 0 |

| Text message | 0 | 0 | 0, 0 |

| Interpreter | 1 | 4 | 5, 2.96 |

| Disposition | |||

| Patients needs were met at the time of visit | 55 | 74 | 129, 76.33 |

| Outcome pending | 20 | 16 | 36, 21.3 |

| Onsite visit—emergent | 0 | 1 | 1, 0.59 |

| Complexity issues of encounter | |||

| Literacy—English was not the primary language | 1 | 3 | 4, 2.37 |

| Poor health literacy | 0 | 2 | 2, 1.18 |

| Parental anxiety | 0 | 0 | 0, 0 |

| Socioeconomic limitations | 1 | 0 | 1, 0.59 |

| Parent developmentally limited | 0 | 0 | 0, 0 |

| Audio problem/failure | 10 | 6 | 16, 9.47 |

| Visualization problem/failure | 5 | 7 | 12, 7.10 |

| Time spent, min | |||

| Preparation time (chart review, etc.) | 10.73 | 6.74 | 8.46 |

| Online | 52.76 | 26.86 | 38.27 |

| Follow-up (orders, documentation, etc.) | 14.85 | 10.27 | 12.37 |

| Total visit time |

TABLE 2.

Parents’ perceptions of their child's telehealth visit

| Item | Agree, n, % | Neutral, n, % | Disagree, n, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| I feel that this visit was beneficial in meeting my/my child's needs | 78, 97.5 | 2, 2.5 | 0, 0 |

| The nurse practitioner gave me her full attention during the visit | 79, 98.75 | 1, 1.25 | 0, 0 |

| There was enough time in the visit for me to process the information shared | 78, 97.5 | 1, 1.25 | 1, 1.25 |

| I had enough time to ask questions | 78, 97.5 | 0, 0 | 2, 2.5 |

| The process of connecting to the telehealth visit was easy to do | 66, 82.5 | 5, 6.25 | 9, 11.25 |

| I thought the quality of video was good | 67, 83.75 | 8, 10 | 5, 6.25 |

| I thought the quality of the (video and) sound were good | 63, 78.75 | 10, 12.5 | 7, 8.75 |

| I did not have any concerns regarding privacy | 79, 98.75 | 0, 0 | 1, 1.25 |

| I feel that my experience with telehealth was as good as if I were in an office visit | 43, 53.75 | 20, 25 | 17, 21.25 |

| I would participate in a telehealth visit again | 78, 97.5 | 1, 1.25 | 1, 1.25 |

Act

Using the results from the Provider and Parent/Patient Data forms and information from the weekly QIP team debriefing sessions, specific health equity issues were identified and categorized according to the domain: availability, accessibility, and acceptability. A toolkit was then developed (see Table 3 ). Strategies for some issues were deemed ready for immediate deployment, such as the flashcards to use with technological difficulties or working with schedulers to improve care coordination. Other concerns were outside of the GI NPs’ immediate scope of practice, such as connectivity issues with the TH platforms. Meetings were held with the respective personnel from other divisions in the hospital to share QIP data while suggesting potential solutions. Finally, other strategies will be further tested in future QIP or formal research studies on the basis of urgency, complexity, and feasibility. For example, anecdotal information suggested that some families encountered extra expenses when trialing different formulas or copays associated with obtaining laboratory work or unanticipated patient emergency department visits and/or hospital admissions; additional data are needed to better understand the scope of the problem before positing solutions.

TABLE 3.

Telehealth toolkit components to address health equity concerns

| Availability: The sufficient supply and appropriate stock of health workers, with the competencies and skill‐mix to match the health needs of the population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concern | Examples | Proposed solutions and resources |

| NP competencies | No specific TH training |

|

Useful materials:

|

||

| Current NP students not receiving training in conducting TH visits |

|

|

Useful materials:

|

||

| Interpreter services and availability | Limited English proficiency |

|

| Deaf or hard of hearing |

|

|

| Adequate visit time | More time needed for physically and socially complex patients |

|

| Need to maximize revenue to reflect the complexity of care provided |

|

|

Useful materials:

|

||

| Accessibility: Requires eliminating physical, financial, cultural, and socioemotional barriers to care | ||

| Physical barriers | Equipment: Underpowered or older hardware/outdated operating systems |

|

| Connectivity (patients): Difficulty downloading the application, compatibility issues, limited patient Wi-Fi ability | For patients and families:

|

|

| Connectivity (providers): Audio failure during the call | For organizations and providers:

|

|

Useful materials:

|

||

| Financial barriers | Economic well-being: Loss of employment affecting insurance coverage, ability to pay prescription copays, purchase formula, etc. |

|

| Copays: Extra copays associated with obtaining laboratory work, unanticipated patient emergency department visits, and/or hospital admissions |

|

|

| Technology costs: Data costs for families with limited. Families report needing to buy extra equipment, data costs |

|

|

| Obtaining weights: Families needing to buy the scale |

|

|

Useful materials:

|

||

| Formula trials: Unable to give samples for families to try, necessitated more Rx and associated costs |

|

|

| Cultural, socioemotional barriers | Embarrassed by the living situation; do not want to show inside of the house |

|

| Poor health literacy |

|

|

Useful information:

|

||

| The reading level of introductory TH e-mails are too high | Check all reading levels for all patient/parent materials before dissemination; keep reading level ≤ grade 5; format appropriately reading levels can be calculated in numerous ways. One easy way is to use the function in Microsoft Word | |

| Useful information: | ||

| Standardized agency TH e-mails only written in English, precluding all patients from accessing information |

|

|

| Care coordination: Travel concerns when initial TH visit scheduled with NP who sees patients at a distant site |

|

|

| Clinical care barriers | Standardized templates |

|

| Physical examination |

|

|

| Specimen collection Supplies not readily available |

|

|

| Acceptability: Entails creating a health care setting free of discrimination. It is based on providing respectful and responsive services as seen through the child's and family's eyes | ||

| Privacy and professionalism |

|

|

| Creating trust virtually |

|

|

| Patient concerns |

|

|

Note. NP, nurse practioner; TH, telehealth; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; COPPA, Children's Online Privacy Protection Act. Selected items were also reported byArmbruster et al. (2020), Berg et al. (2020), Dorsey & Topol (2016), Orlando, Beard, & Kumar (2019), and Kemery and Goldschmidt (2020).

RESULTS

Interpretation

Every indication was that TH would become fully integrated into health organizations’ care delivery. In a recent survey, McKinsey & Company reported that 76% of consumers want to use TH services moving forward, 57% of providers view TH more favorably, and 67% were comfortable with TH, and regulatory requirements have been widely expanded (Bestsennyy et al., 2020). For TH to reach its potential in providing equitable, high-quality care to patients and families, prioritization must be given to addressing the impact of social determinants of health on implementation strategies (Park et al., 2018).

In this QIP, connectivity and communication were the major issues encountered. Our hospital uses a variety of technological interfaces. Synchronous video-based conferencing programs such as Zoom (Zoom, 2020), Doximity (Doximity, 2020), and SBR (SBR Health, 2020) were used for actual clinic visits. SBR (SBR Health, 2020) is designed specifically for TH and is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant. Unfortunately, in this project, it was associated with connectivity issues, primarily lower socioeconomic families who had technology with minimal capacity (i.e., chrome books). It also did not allow more than two parties (patient and provider) to participate at a time, limiting real-time care coordination. Doximity (Doximity, 2020) is a network for health care professionals used for calling patients using their office phone number, video conferencing, and faxing HIPAA compliant patient documents such as instructions, prescriptions, and clinic notes to sharing providers. These can occur while not disrupting personal cell phone information to conduct TH practices. Zoom (Zoom, 2020) is a video communication program that allows for HIPAA compliant video conferencing across all professional domains. For nonurgent issues, asynchronous platforms such as the patient portal, secure e-mail, and telephone calls were used to communicate with patients.

Patient/family failure to successfully download apps, insufficient bandwidth, and interrupted transmission were all encountered, although the immediate five-state geographic area has some of the best broadband connectivity in the country (Cooper, 2018). Difficulty accessing an interpreter and maintaining interpreter services if technological difficulties occurred was also a concern. Although a technology helpdesk was available to all patients, families, and providers, delayed response times and the complexity of the issue often required that the visit be rescheduled.

Diverse platform options are recommended to meet the needs of different patient subgroups to improve TH adoption and use (Armbruster et al., 2020). Although multiple technologies can enhance communication, they also require that families are capable of using and monitoring multiple electronic information sources. When families failed to see electronic visit planning messages or successfully download connectivity software, visits were interrupted, canceled, or missed altogether. Ensuring that families were fully prepared for the TH visit was a challenge if all the visit preparation e-mails were not read or followed. For example, a common problem was that the child was not weighed before the visit. Another surprising issue was parents who did not include their child in the TH visit.

An organizational-wide plan is essential for TH to be both efficient and efficacious (Alverson et al., 2008); ideally, it should be designed for multiple family members (i.e., both parents, adolescent patients) to synchronously receive the same messages and participate in the calls when prudent. Examples include divorced families with shared custody or when the patient was at college, but their parent was at home. Prompts for families in which English is not the preferred language, standardized symbols, quick response codes, and other prompts on all materials will alert families regarding translation services.

Limited Internet and mobile band access and data fees sustain the digital divide across socioeconomic groups (Anderson & Kumar, 2019; Steele, 2016). As new, more sophisticated modalities are adopted by an organization, attention must be paid to their compatibility with basic technological devices and the amount of data time they use so as not to shut out lower socioeconomic populations. Formalized backup plans for poor Internet-based connectivity are essential (Brophy, 2017).

During the data collection for this QIP, TH visits were the only option for nonemergent visits for either new or continuing patients. Generally, the GI NPs thought that TH was an excellent platform for most follow-up visits but establishing therapeutic relationships with some new patients was more difficult than when initial visits were conducted in-person. Social capital factors such as trust and engagement with the provider and organization are known to significantly positively affect patients’ perceived ease of use of, the usefulness of, and intention to use TH (Tsai, 2014). Incorporating these into TH protocols, using in-clinic visits for new patients, and maintaining the same provider are strategies that should be considered (Dorsey & Topol, 2016; Orlando, Beard, & Kumar, 2019). This QIP was not designed to capture routine follow-up visits that went unscheduled or those that were missed despite being scheduled. However, the GI NPs’ anecdotal impressions were that the patients and families might have lacked knowledge on how to use the technology or had health literacy concerns. Auditing missed visits and determining associated factors would help illuminate this issue and lead to better care coordination.

The inability to conduct a physical examination for some patients was problematic. Even with inspection, assessment capabilities were limited by the quality of the patient's and provider's cameras. When a physical examination was essential, TH alone was insufficient and may have contributed to health inequalities.

TH also prevented seamless transitions in care. When laboratory tests or other simple diagnostic procedures were ordered, they could not be completed at the time of the visit. The GI NPs reported that patients and families had to schedule separate appointments for diagnostic examinations, laboratory studies, or x-rays. Access to free formula samples and timely consultation with the attending were also not always available. These follow-up visits required families to assume the cost and time burdens associated with travel, parental leave time, extra copays, and others. Delayed care could also be an issue. All contribute to excess health care use (Dorsey & Topol, 2016).

The literature supports that additional training in TH procedures is needed by experienced clinicians (Brophy, 2017; Clay-Williams et al., 2017). For example, in this QIP, the GI NPs had to modify their practices to match available technology. Preplanning and record review was essential. Having only a small laptop screen to use when conducting the visit, visual contact with parents and patients was interrupted when the GI NPs had to switch among screens to review information in the electronic medical record, consult formularies, order laboratory tests, and others. Including audio cues were necessary so that patients remain engaged. Interruptions in visual engagement interfere with the therapeutic relationship, critically important in advancing health equity for all families (Kemery & Goldschmidt, 2020). The GI NPs also needed to provide additional instruction not needed in in-clinic settings. For example, parents needed to be reminded that their child needed to be present for the TH visit. Documentation and coding strategies needed to be modified to capture total visit time, not just time “on camera.” Training specific to Children's Online Privacy Protection Act regulations that place parents in control of providing personal information from children under the age of 13 years and the need for providers to share with parents/guardians about how such information will be used needed to be provided (Federal Trade Commission, 2017).

Finally, health care organizations must heed human factors and ergonomics principles when implementing TH (Carayon, 2017). For NPs conducting TH from their homes, computers configured with high-quality visual and audio capabilities, embedded decision support systems, and dual screens will maximize patient assessment and communication while meeting patient privacy concerns. Ergonomically correct workstations will help prevent provider injury.

Limitations

Albeit the information gleaned from this QIP is enlightening and useful, this project included only a small number of NPs from a single pediatric subspecialty outpatient clinic where customarily the visits are conducted in-person. The model of care is highly interdisciplinary, typically including not only NPs but clinical nurses, physicians and physician trainees, social workers, dieticians, and professional personnel such as pharmacists. Administrative staff also are part of the care delivery model. Although all these individuals contribute to the work of the GI ambulatory clinic, they were not included in this exploratory project. The parent/family sample size (n = 80) was adequate but modest. In addition, the data collection tools used for the project were not validated instruments. Securing financial information such as comparing family expenses when conducting TH visits with in-person visits, rates of reimbursement for NP TH with in-person visits would all have added value to this project. Finally, families were not part of the team that planned this initiative, given the project emerged in the setting of a pandemic.

Conclusions

All indications are that TH will remain fully integrated into care delivery in the postpandemic era. Strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation were required to ensure that delivery strategies are designed to be “value added” by enhancing health equity for the children and families for whom we care.

Biographies

Jessica Serino-Cipoletta, RN Project Manager, Clinical Research Operations Center, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Catherine Dempsey, Research Nurse, Clinical Research Operations Center, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Nancy Goldberg, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Division of Gastroneterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Barbara Marinaccio, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Division of Gastroneterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Kimberli O'Malley, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Division of Gastroneterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Caitlin Dolan, GI NP Clinical Coordinator, Division of Gastroneterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Lori Parker-Hartigan, Clinical Coordinator, Division of Gastroneterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Lucinda Williams, Nursing Director, Experimental Therapeutics Unit, and Co-Director, Clinical Research Operations Center, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA.

Judith A. Vessey, Nurse Scientist, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA; and Lelia Holden Carroll Professor in Nursing, Boston College, William F. Connell School of Nursing, Chestnut Hill, MA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors, who have no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The design and conduct of this quality improvement project was in keeping with the institution's guidelines specific to the conduct of quality initiatives; it was determined that this quality improvement project was exempt from institutional review board review.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.01.007.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- Alverson D.C., Holtz B., D'Iorio J., DeVany M., Simmons S., Poropatich R.K. One size doesn't fit all: Bringing telehealth services to special populations. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health. 2008;14:957–963. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M., Kumar M. 2019. Digital divide persists even as lower-income Americans make gains in tech adoption.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/07/digital-divide-persists-even-as-lower-income-americans-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster M., Fields E.L., Campbell N., Griffith D.C., Kouoh A.M., Knott-Grasso M.A.…Agwu A.L. Addressing health Inequities exacerbated by COVID-19 among youth with HIV: Expanding our toolkit. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum F., MacDougall C., Smith D. Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60:854–857. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg E.A., Picoraro J.A., Miller S.D., Srinath A., Franciosi J.P., Hayes C.E.…LeLeiko N.S. COVID-19-A guide to rapid implementation of telehealth services: A playbook for the pediatric gastroenterologist. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2020;70:734–740. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestsennyy O., Gilbert G., Harris A., Rost J. 2020. Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality?https://www.the-digital-insurer.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/1658-McKinsey-Telehealth-A-quarter-trilliondollar-post-COVID-19-reality.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. The role of telehealth in an evolving health care environment: Workshop summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy P.D. Overview on the challenges and benefits of using telehealth tools in a pediatric population. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 2017;24:17–21. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P., editor. Handbook of human factors and ergonomics in health care and patient safety. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Health equity.https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity/index.htm Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Chaet D., Clearfield R., Sabin J.E., Skimming K., Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs American Medical Association Ethical practice in telehealth and telemedicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2017;32:1136–1140. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay-Williams R., Baysari M., Taylor N., Zalitis D., Georgiou A., Robinson M.…Westbrook J. Service provider perceptions of transitioning from audio to video capability in a telehealth system: A qualitative evaluation. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17:558. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2514-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T. 2018. US states with the worst and best internet coverage 2018.https://broadbandnow.com/report/us-states-internet-coverage-speed-2018/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A., Serhal E. Digital health equity and COVID-19: The innovation curve cannot reinforce the social gradient of health. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22:e19361. doi: 10.2196/19361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dávalos M.E., French M.T., Burdick A.E., Simmons S.C. Economic evaluation of telemedicine: Review of the literature and research guidelines for benefit-cost analysis. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health. 2009;15:933–948. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey E.R., Topol E.J. State of telehealth. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375:154–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1601705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doximity . 2020. Doximity.https://www.doximity.com/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Fardi Z., Grunbaum J.A., Gray B.S., Franks A., Simoes E. Community-based participatory research: Necessary next steps. Prevention in Chronic Disease. 2007;4:A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission . 2017. Children's online privacy protection rule (“COPPA”)https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/rules/rulemaking-regulatory-reform-proceedings/childrens-online-privacy-protection-rule Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- HealthIT.gov . 2017. September 28.Telehealth and telemedicine.https://www.healthit.gov/topic/health-it-initiatives/telemedicine-and-telehealth Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson K., Davis T.C., Smith M., King M. Nurse practitioners in telehealth: Bridging the gaps in healthcare delivery. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2014;10:845–850. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (n.d.). How to improve. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

- Jones C.P., Jones C.Y., Perry G.S., Barclay G., Jones C.A. Addressing the social determinants of children's health: A cliff analogy. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20:1–12. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemery D.C., Goldschmidt K. Can you see me? Can you hear me? Best practices for videoconference-enhanced telemedicine visits for children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2020;55:261–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse C.S., Krowski N., Rodriguez B., Tran L., Vela J., Brooks M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvedar J., Coye M.J., Everett W. Connected health: A review of technologies and strategies to improve patient care with telemedicine and telehealth. Health Affairs. 2014;33:194–199. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrinc G., Davies L., Goodman D., Batalden P.B., Davidoff F., Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2016;25:986–992. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando J.F., Beard M., Kumar S. Systematic review of patient and caregivers' satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients' health. PloS one. 2019;14:e0221848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Erikson C., Han X., Iyer P. Are state telehealth policies associated with the use of telehealth services among underserved populations? Health Affairs. 2018;37:2060–2068. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SBR Health . 2020. About SBR.https://www.sbrhealth.com/about-sbr Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- SQUIRE . 2020. Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence.http://squire-statement.org Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Steele B. 2016. Poor cell phone coverage creates a ‘mobile divide’.https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2016/05/poor-cell-phone-coverage-creates-mobile-divide Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C.H. Integrating social capital theory, social cognitive theory, and the technology acceptance model to explore a behavioral model of telehealth systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11:4905–4925. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110504905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Michigan, Population Studies Center, Institute for Social Research. Morenoff J. 2011. Zip code characteristics: Mean and median household income.http://www.psc.isr.umich.edu/dis/census/Features/tract2zip Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Utidjian L., Abramson E. Pediatric telehealth: Opportunities and challenges. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2016;63:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey J.A., McCrave J., Curro-Harrington C., DiFazio R.L. Enhancing care coordination through patient- and family-initiated telephone encounters: A quality improvement project. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2015;30:915–923. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoom . 2020. Zoom Video Communications.https://zoom.us/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.