Abstract

Sixty-seven Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor isolates (36 domestic and 31 imported) were classified into 19 subtypes by NotI- and SfiI-digested pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Twenty-five of 36 domestic and 4 imported isolates were assigned to a NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 subtype, suggesting that this pulse type is widely distributed in Asia and Japan.

The cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor that originated in Indonesia in 1961 has spread to Southeast Asia, the Indian Subcontinent, the Near East, Africa, and South America (the seventh pandemic) (2–4, 10, 12). Although cholera cases in Japan were restricted mainly to returnees from areas where cholera is endemic (referred as imported cases), those among people with no recent experience of travel abroad (referred to as domestic case) have been noticeably increasing in recent years. In 1997, sporadic cholera cases involved 101 people in Japan, 36 of whom had no history of overseas travel, and were found in 17 separate prefectures of Japan (9).

In order to investigate the origin of strains in domestic cases, a total of 67 strains of V. cholerae O1 biotype El Tor isolated in 1997 in Japan were analyzed by phage typing, drug susceptibility, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) after digestion with NotI and SfiI. Thirty-six strains were isolated from patients who had not gone abroad, and 31 strains were isolated from patients who had just returned from Thailand, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, China, and Korea. Fourteen V. cholerae O1 biotype El Tor isolates derived from outbreaks in Japan and other countries before 1997 were used as references.

Phage typing was done by the method of Mukerjee (7). Susceptibility of V. cholerae O1 strains to a variety of antimicrobial agents was determined by the disc diffusion method (8) using discs containing ampicillin (AMP), chloramphenicol (CHL), kanamycin (KAN), tetracycline (TET), streptomycin (STR), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) (BBL Sensi-Disc; Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) and the vibriostatic agent O/129 (Oxoid). The zones of inhibition around the discs were measured and compared with established zones for sensitivity described by the manufacturers for individual antimicrobial agents.

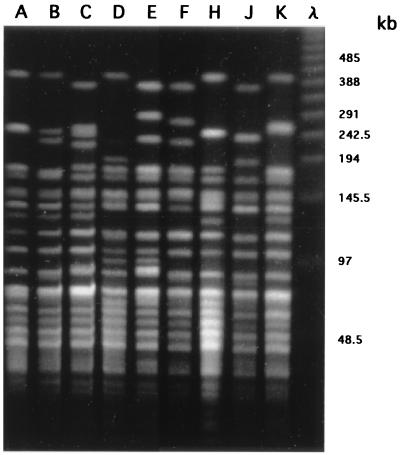

Extraction of genomic DNAs and PFGE analysis were done as previously described (6). In brief, bacterial cells were embedded in low-melting-point agarose (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) and lysed with lysis buffer (1% Sarkosyl in 0.5 M EDTA [pH 8.0]) containing lysozyme and proteinase K. The DNAs were digested with 20 U of restriction endonuclease NotI or SfiI (New England Biolabs, Boston, Mass.) at 37 or 50°C, respectively. PFGE was performed with a 1% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 10°C by using a CHEF DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 6 V/cm with a linearly ramped switching time of 4 to 8 s for 9 h and further at 8 to 50 s for 11 h. PFGE patterns were classified basically as proposed by Tenover et al. (11); when four or more bands in the PFGE patterns were different from each other, we designated them as distinct types, A to K (Fig. 1). When one or more fragments were different among strains with the same type, we assigned them to distinct subtypes designated by Arabic numerals.

FIG. 1.

Representative PFGE patterns of V. cholerae O1 strains cleaved with restriction enzyme NotI. Lanes A to K show the representative PFGE patterns of the types and subtypes (A1, B1, C1, D, E2, F1, J, and K, respectively) shown in Table 1 (D, F1, and J were derived from isolates of domestic outbreaks during the past 2 decades). λ is a 48.5-kb ladder size marker. The values on the right are sizes in kilobases.

Sixty-six of 67 V. cholerae O1 El Tor strains belonged to serotype Ogawa, and only 1 belonged to serotype Inaba. Their phage types were 4 and NS (not sensitive to all phages), and all of the NS strains were isolated from patients who visited Asia (Table 1). Sixty-seven strains, all of which were sensitive to AMP, CHL, KAN, and TET, were separated into six groups with respect to susceptibility to STR, SXT, and O/129 and phage types (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of V. cholerae O1 isolates from domestic and imported cases of cholera in 1997

| Phage type | Drug susceptibilitya

|

PFGE type

|

No. of cases | Patient residence or travel location (no. of patients) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STR | SXT | O/129 | NotI | SfiI | |||

| Domestic casesb | |||||||

| 4 | − | + | + | A1 | A1 | 24 | Tokyo (6), Kanagawa (5), Chiba (3), Osaka (2), Saitama (1), Kyoto (1), Kagoshima (1), Fukushima (1), Aichi (1), Shiga (1), Niigata (1), Oita (1) |

| 4 | ± | + | + | A1 | A1 | 1 | Tochigi (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A1 | A8 | 1 | Tokyo (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A1 | A11 | 1 | Osaka (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A2 | A2 | 3 | Tokyo (2), Akita (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A2 | A3 | 1 | Tokyo (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | K | M2 | 2 | Miyagi (1), Chiba (1) |

| 4 | + | + | + | B7 | L2 | 1 | Gifu (1) |

| 4 | + | + | + | E2 | M1 | 2 | Hyogo (2) |

| Imported casesc | |||||||

| 4 | − | + | + | A1 | A1 | 4 | Indonesia (1), China (1), Thailand (1), Korea (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A1 | A6 | 1 | Philippines (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A1 | A9 | 1 | Philippines (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A2 | A3 | 1 | Philippines (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A3 | A4 | 1 | Philippines (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | A6 | A1 | 1 | China (1) |

| 4 | − | − | − | B1 | B1 | 1 | China (1) |

| NSd | − | − | − | B1 | B1 | 10 | Thailand (10) |

| NS | − | + | + | B1 | B1 | 1 | Singapore (1) |

| NS | − | + | + | B2 | B2 | 1 | Thailand (1) |

| NS | − | + | + | B2 | B6 | 1 | Thailand (1) |

| 4 | − | − | − | B3 | B3 | 1 | India (1) |

| 4 | + | + | + | B6 | L1 | 3 | Indonesia (2), Singapore (1) |

| 4 | − | − | − | B6 | L1 | 1 | Indonesia (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | C1 | C | 1 | Indonesia (1) |

| 4 | − | + | + | C2 | A5 | 2 | Indonesia (2) |

Symbols: +, sensitive; −, resistant; ±, intermediate. All strains were sensitive to AMP, CHL, KAN, and TET.

The total number of domestic cases was 36.

The total number of imported cases was 31.

NS, not sensitive to any of the phages used.

Figure 1 shows the representative NotI-digested PFGE patterns of V. cholerae O1 isolate types A to K. The NotI- and SfiI-digested PFGE patterns of the 67 strains are summarized in Table 1. Of the domestic cases, 86.1% (31 of 36) belonged to the NotI-A–SfiI-A PFGE type. Twenty-five of the 31 strains were subtyped to NotI-A1–SfiI-A1, and these were isolated independently from patients in separate parts of Japan, as shown in Table 1. On the other hand, imported cases were separated into 13 subtypes, 1 of which was the NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 subtype, which is indistinguishable from the dominant PFGE subtype of the domestic cases. Strains of the NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 subtype were isolated from four patients who visited Indonesia, China, Thailand, and Korea in 1997 (Table 1). Isolates with the same PFGE pattern were also obtained from patients who visited Korea and Indonesia in 1994 and 1995, respectively (data not shown). We did not find any subtype NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 strains among the isolates from domestic outbreaks that occurred during the past 2 decades (data not shown).

The rates of occurrence of domestic cholera cases among persons with no history of overseas travel were 5.8, 2.9, 21.0, 8.3, and 21.0% from 1992 to 1996 in Japan, respectively. In 1997, the rate of occurrence of such cases increased to 35.6%, all of which were found in separate areas of Japan as sporadic cases (9). Individual investigations were done by the prefectural governments where the sporadic cases were found, and no apparent link between these cases and food and drink ingestion and contact with overseas travelers was found. However, the finding that 25 of 36 domestic cases were caused by isolates with identical phenotypes and genotypes, that is, phage type 4, resistance to STR (only 1 case was intermediate), and the NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 PFGE subtype suggested that the clonal V. cholerae O1 strains have spread to various parts of Japan and sporadically caused cholera.

Four strains isolated from patients who had visited Indonesia, China, Thailand, and Korea (imported cases) were indistinguishable from those isolated from the domestic cases in terms of their phenotypes and genotypes (NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 PFGE subtype). We found a further two strains of the NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 PFGE subtype which were isolated in 1994 and 1995 from patients who had been to Korea and Indonesia, respectively. These results suggested that the NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 PFGE clone of V. cholerae O1 has recently spread among Asian countries and that the clone associated with the sporadic domestic cases in Japan must be linked to the clone prevailing in Asia (5, 13).

The exact reason why diarrheal disease caused by the clonal V. cholerae O1 strains has occurred sporadically in Japan is not known. Several hypotheses may be plausible. First, the rivers, seas, and other parts of Japan have been contaminated by V. cholerae O1, which seems to be unlikely because V. cholerae O1 strains have seldom been isolated from the environment in Japan, irrespective of routine intensive investigations by local governments. However, we do not rule out the possibility that V. cholerae O1 strains exist in the environment of Japan under a viable but nonculturable state. Second, domestic cholera patients might have had contact with patients returning from countries whose cholera is prevalent. This is also not likely because such contact could not be found in any of the cases and also the number of domestic cases caused by isolates with the NotI-A1–SfiI-A1 PFGE subtype was much higher than that of imported cases caused by isolates with the same PFGE subtype (Table 1). Third, it is most probable that foods which had been contaminated by the clonal V. cholerae O1 isolate were imported, delivered to various parts of Japan, and eaten. In order to elucidate this hypothesis, further epidemiological and bacteriological investigations are required. Moreover, this study clearly shows that PFGE analysis is a powerful tool for evaluation of relationships among strains isolated in separate areas (1).

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the prefectural and municipal public health institutes and quarantines in Japan that kindly provided V. cholerae O1 strains.

This work was supported by a grant (H10-Sinkou-16) from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cameron K N, Khambaty F M, Wachsmuth I K, Tauxe R V, Barrett T J. Molecular characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;30:1685–1690. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1685-1690.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coelho A, Andrade J R, Vicente A C, Salles C A. New variant of Vibrio cholerae O1 from clinical isolates in Amazonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:114–118. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.114-118.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalsgaard A, Skov M N, Serichantalergs O, Echeverria P, Meza R, Taylor D N. Molecular evolution of Vibrio cholerae O1 strains isolated in Lima, Peru, from 1991 to 1995. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1151–1156. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1151-1156.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De S N, Mukerjee B, Dutta A R. Is it El Tor Vibrio in Culcutta? J Infect Dis. 1965;115:337–381. doi: 10.1093/infdis/115.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyobu T, Hosorogi S, Shimada T. Analysis of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolated in Japan by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Kans ensho gaku Zasshi. 1998;72:575–584. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.72.575. . (In Japanese.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izumiya H, Terajima J, Wada A, Inagaki Y, Itoh K-I, Tamura K, Watanabe H. Molecular typing of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolated in Japan by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1675–1680. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1675-1680.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukerjee S. Principles and practice of typing Vibrio cholerae. Methods Microbiol. 1978;12:52–115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. 5th ed. Vol. 13. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute of Infectious Diseases and Infectious Diseases Control Division, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Cholera in Japan, 1985–1997. Infect Agents Surveillance Rep. 1998;19:97–98. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma C, Ghosh A, Dalsgaard A, Forslund A, Ghosh R K, Bhattacharya S K, Nair G B. Molecular evidence that a distinct Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor strain in Calcutta may have spread to the African continent. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:843–844. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.843-844.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wachsmuth I K, Evins G M, Fields P I, Olsvic O, Popovic T, Bopp C A, Wells J G, Carillo C, Blake P A. The molecular epidemiology of cholera in Latin America. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:621–626. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittlinger F, Steffen R, Watanabe H, Handszuh H. Risk of cholera among Western and Japanese travelers. J Travel Med. 1995;2:154–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.1995.tb00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]