Abstract

Background:

Successful delivery of gene-editing tools using nano-carriers is dependent on the ability of nanoparticles to pass through the cellular membrane, move through the cytoplasm, and cross the nuclear envelope to enter the nucleus. It is critical that intracellular nanoparticles interact with the cytoskeletal network to move toward the nucleus, and must escape degradation pathways including lysosomal digestion. Without efficient intracellular transportation and nuclear entry, nanoparticles-based gene-editing cannot be effectively used for targeted genomic modification.

Objective:

We have developed nanoparticles with a low molecular weight branched polyethyleneimine lipid shell and a PLGA core that can effectively deliver plasmid DNA to macrophages for gene editing while limiting toxicity.

Methods:

Core-shell nanoparticles were synthesized by a modified solvent evaporation method and were loaded with plasmid DNA. Confocal microscopy was used to visualize the internalization, intracellular distribution and cytoplasmic transportation of plasmid DNA loaded nanoparticles (pDNA-NPs) in bone marrow-derived macrophages.

Results:

Core-shell nanoparticles had a high surface charge of +56 mV and narrow size distribution. When loaded with plasmid DNA for transfection, the nanoparticles increased in size from 150 nm to 200 nm, and the zeta potential decreased to +36 mV, indicating successful encapsulation. Further, fluorescence microscopy revealed that pDNA-NPs crossed the cell membrane and interacted with actin filaments. Intracellular tracking of pDNA-NPs showed successful separation of pDNA-NPs from lysosomes, allowing entry into the nucleus at 2 hours, with further nuclear ingress up to 5 hours. Bone marrow-derived macrophages treated with pDNA/GFP-NPs exhibited high GFP expression with low cytotoxicity.

Conclusion:

Together, this data suggests pDNA-NPs are an effective delivery system for macrophage gene-editing.

Keywords: Cytoplasmic trafficking, nuclear ingress, branched PEI lipid, core-shell NPs, plasmid DNA transfection, macrophages

1. INTRODUCTION

Plasmid-based gene editing has provided great potential as the next generation of therapeutic applications in many areas of research. The most common method of non-viral gene delivery is high molecular weight polyethylenimine (PEI) [1–4]. One of the unique advantages of lipid-based cationic vectors is that the cationic polar head group can bind DNA through electrostatic interactions, while the hydrophobic chain can self-assemble into micelles that permeabilize the cell membrane. High molecular weight PEIs (MW25000) have been reported to exhibit high gene expression in dividing cells by binding to the surface of cells and releasing plasmid DNA (pDNA) from endosomes [5–8]. However, due to the presence of long alkyl chains required for stabilization, high MW PEI lipids can damage cell membranes and cause severe cytotoxicity. Moreover, they can cause undesirable gene expression and blood aggregation [9–13]. Other limitations include endolysosomal degradation and poor nuclear entry [14–18]. To address these challenges, it is necessary to develop a gene delivery system that can capture and transport large molecules such as exogenous genes into the nucleus with no cytotoxicity.

The development of gene-editing delivery systems, including nanoparticles (NPs), has mainly focused on “best” carriers. However, intracellular trafficking is fundamental for efficient pDNA transfection and gene editing. Successful gene delivery is dependent on the uptake, trafficking, and nuclear ingress of pDNA loaded NPs (pDNA-NPs). It is also critical that the intracellular pDNA-NPs escape from lysosomes and interact with the cytoskeletal network to move toward the nucleus. We have developed core-shell NPs with biochemical properties that can circumvent these challenges and provide high delivery efficiency of pDNA for gene editing. NPs are synthesized from low MW branched PEI (MW800) lipids. The most unique feature of our PEI lipid is the ring-opening reaction of glycidyl hexadecyl ether (EpoxyC16; tail group) by primary and secondary amines from low MW branched PEI (head group) [19]. Interestingly, by adding poly (D,L-lactide-co-glycolide; PLGA) as the core to the PEI lipid, we were able to create a core-shell NP-based gene delivery system that transported pDNA to the nucleus without endolysosomal degradation. This yields high transfection efficiency and gene expression. In our previous work, core-shell NPs were successfully utilized for various gene and drug therapies [19–21].

Gene-editing for immune manipulation and regulation has attracted great attention as a promising immunotherapy [22–27] for anti-cancer, anti-inflammation, severe combined immune deficiency, chronic disorders, and aging. Macrophages are often targeted for immunotherapy because they are involved in cancer growth, infection, inflammation and repair [28–30]. However, the significant challenge of macrophage gene-editing is nuclear delivery. Despite the number of carriers available [31–36], several biological barriers appear to limit the effectiveness of gene editing in macrophages. First, negatively charged pDNA cannot cross cellular membranes, escape from lysosomes, or enter the nucleus. Second, the phagocytic and non-dividing features of macrophages are major factors hindering the bioavailability of pDNA and sustained therapeutic effects. Understanding the fundamental basis of these biological barriers has aided in establishing methods to improve the efficiency of PEI-NP gene delivery systems. It is critical to formulate a carrier that can facilitate cellular uptake and maintain stability for intracellular trafficking and nuclear translocation. This can be achieved by encapsulating pDNA in NPs with physicochemical properties that allow it to cross the cell membrane, escape lysosomes and reach the nucleus with better pDNA stability for gene-editing.

Increasing evidence has suggested that intracellular transportation of NPs largely affects gene delivery and pDNA transfection [37, 38]. Optimal intracellular trafficking can, therefore, significantly improve NP-based gene delivery and biological outcomes. Because of the unique characteristics aforementioned, we used macrophages as a platform to specifically study intracellular trafficking and nuclear delivery of our NPs loaded with IL-4pDNA. The efficacy was determined by examining M2 macrophage polarization due to induced upregulation of IL-4. We labeled pDNA, NPs, and the cell membrane and cellular structures of macrophages with different dyes. These multiple labeling experiments of intracellular events allow better visualization and evaluation of intracellular trafficking. Our study suggested that NPs with a PLGA core and PEI lipid shell enhanced pDNA encapsulation, and promoted cellular uptake, endolysosomal escape, and nuclear entry for efficient transfection with lowered toxicity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Synthesis of PEI Lipid

To obtain PEI lipids, glycidyl hexadecyl ether (GHE) (MW = 298 g/mol; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and low molecular weight branched PEI (MW = 800 g/mol; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) were mixed in a glass vial at a molar ratio of 8:1. The vial was sealed and the samples were stirred at 300rpm for 24 hours at 40°C. Afterward, the sample was cooled to room temperature and the obtained white solid was broken down into a fine powder and stored at 4°C.

2.2. PLGA/PEI NPs Formulation and Characterization

NPs were prepared by a modified solvent extraction/evaporation method [19, 39]. Briefly, 25 mg of PEI lipid, 15 mg of Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (50/50) (PLGA; LACTEL Absorbable Polymers, Birmingham, AL) and 2 mg of 1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycerol, Methoxypolyethylene Glycol (DMG-PEG; NOF America, White Plains, NY) were dissolved in 0.5 mL dichloromethane (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). 0.3 mg Rhodamine 6G (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was added to label NPs. The solution was mixed with 2.5 mL DD water then sonicated to obtain a fine emulsion. The emulsion was further stirred overnight at room temperature then filtered with an Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter (molecular weight cutoff of 100kDa; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). The suspension was adjusted to 2.5 mL with DD water and stored at 4°C.

Scanning electron microscopy (JEOL, Model: JSM-6010LA, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) and atomic force microscopy (Park Systems, Model: XE-100, Santa Clara, CA) were used to observe NP morphology. A zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, Model: Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern, United Kingdom) was used to measure the size distribution, zeta potential, and heterogeneity of the obtained NPs.

2.3. IL-4pDNA Encapsulation

NPs were loaded with human IL-4pDNA or human IL-4/GFPpDNA (Sino Biological, Wayne, PA) at a concentration of 2.5ug PEI (based on the total PEI used to make the NP) to 1ug of DNA. This ratio was experimentally determined to produce the highest transfection efficiency while reducing cytotoxic effects [19]. The NP:DNA complex was prepared in PBS and was allowed to incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature before transfection.

2.4. Gel Electrophoresis

DNA encapsulation by NPs was investigated by agarose gel electrophoresis. NPs were loaded with pDNA at different N/P ratios and run on a 1% agarose gel for 30 minutes. pDNA was visualized with an Amersham Imager 680 blot and gel imager (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL).

2.5. Macrophage Cultures

To obtain macrophage cultures, mouse (Balb/C, male 4–6 weeks) bone marrow was extracted from the femur and separated into single-cell suspensions. Bone marrow cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and 500 U/ml macrophage-colony stimulating factor (MCSF). The cultures were allowed to differentiate into bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) for 10–12 days. Cells were then scraped, counted, and seeded into appropriate culture plates and allowed to recover for 24 hours before transfection.

All experiments in Balb/C mice were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council. The protocols were approved by the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso (TTUHSC – El Paso) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) at 4 weeks and were raised and maintained by the Laboratory Animal Resource Center at TTUHSC – El Paso.

2.6. IL-4pDNA/GFP-NP Transfection

For transfection of BMM, human IL-4pDNA-NPs or IL-4pDNA/GFP-NPs were added to cells at a 1:20 NPs/media ratio. The media was changed after 4 hours, and the cells were further cultured for 5 days. Cells were imaged with a Nikon Ti Eclipse fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) and analyzed for GFP expression with Image Pro Plus software.

2.7. Labeling of IL-4pDNA and NPs

To visualize NP uptake by BMM, rhodamine was used to label pDNA-NPs (pDNA-rNPs, red; see section 2.2 “PLGA/PEI NPs Formulation and Characterization”). IL-4pD-NA was labeled with BOBO-3 iodide (BOBO-pDNA, red) or YOYO-1 iodide (YOYO-pDNA, green) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 1 dye molecule to 50 pDNA base pairs for 24 hours [19, 40]. NPs were loaded with IL-4-YOYO pDNA (IL-4-YOYO-pDNA-NPs) and added to cultures for intracellular trafficking evaluation.

2.8. Labeling of Lysosomes, Membranes and Cytoskeleton

LysoTracker Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), SlowFade Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI, (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and CellBrite Fix555 (Biotium, Fremont, CA) were used to label the lysosomes, nucleus, and cell membranes, respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Each stain was added prior to transfection for live imaging studies. For cytoskeleton structures, the cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with rabbit F-actin (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), followed by secondary antibody staining with rabbit GFP (green; 1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

2.9. Live Cell Imaging

Fluorescence microscopy was used to image the uptake, intracellular trafficking and transfection of IL-4pDNA-NPs in cultures prepared in an 8-well Lab-Tek ll Chamber Slide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Live cell imaging was performed and scanned every 30 minutes by a Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 and humidity for the duration of the imaging session. For fixed cell imaging, cells were imaged with a confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY).

2.10. Cell Viability LDH Release Assay

BMM cells were seeded in a 96 well plate and transfected 24 hours later as described in “IL-4pDNA/GFP-NP Transfection”. Non-treated cultures served as the control. LDH release was assayed using the Pierce LDH cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol at 1, 3 and 5 days post-transfection. Samples were analyzed with the FlexStation 3 Multi--Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) at 490nm and 680nm, and the % cytotoxicity was calculated. The experiment was repeated in triplicate.

2.11. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

BMM cells were seeded in a 96 well plate and transfected with either human IL-4 or mouse IL-4 pDNA-NPs. ELISA Kits purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) were used to determine IL-4 secretion at 5 days post-transfection. Non-transfected cells served as the control. The supernatant was processed and analyzed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses, including one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis, were carried out in SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY). The variance between groups was similar, and the data were normally distributed. All error bars are expressed as s.e.m. All experiments were repeated in triplicate.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Synthesis of PEI Shell - PLGA Core NPs and pDNA Loading

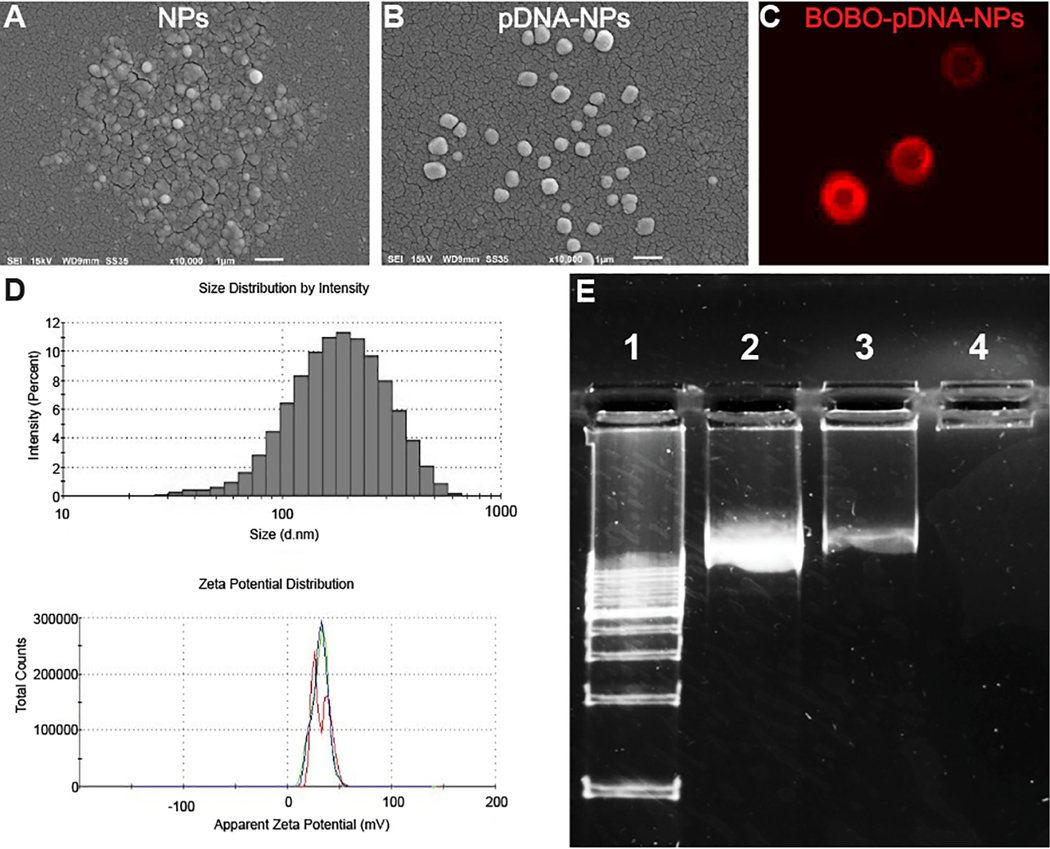

The lipid was synthesized by reacting the hexadecyl chain of GHE (the tail group) with the primary and secondary amines of low MW branched PEI (the head group) at a molar ratio at 8:1. The obtained PEI lipid was used to encapsulate a PLGA core with C16 chains that created a cationic PEI shell. These PLGA core and PEI lipid shell NPs were characterized by SEM, fluorescence microscopy and a zetasizer. SEM images revealed NPs (Fig. 1A) and pDNA-NPs (Fig. 1B) were spherical in shape, had a smooth surface and were monodispersed. The size of NPs was enlarged after loading with pDNA. For visualization of pDNA encapsulation, red dye BOBO was used to label pDNA (BOBO-pDNA). Fluorescence microscopy scanning showed that BOBO-pDNA-NPs (Fig. 1C, red) were captured on the PEI lipid shell of the NPs, displaying a “ring” morphology. The size and zeta potential (Fig. 1D) of NPs and pDNA-NPs were 150 ± 10 nm and 200 ± 6 nm in size, and +56 ± 6 mV and +36 ± 7mV, respectively. The polydispersity index (PDI) of NPs and pDNA-NPs was below 0.3. Together, these data indicate that our newly synthesized NPs are cationic and stable in a colloidal suspension, and are homogeneous in size and shape.

Fig. (1). Characterization of the obtained nanoparticles.

SEM images show NPs (A) and pDNA-NPs (B) are spherically shaped, smooth and are monodispersed. Red dye labeled BOBO-pDNA were encapsulated on the shell of NPs (C), leading to a “ring” morphology under fluorescence microscopy. The size distribution and zeta potential of pDNA-NPs are illustrated in (D). Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of pDNA encapsulation efficiency (E). Lanes 1 and 2 represent the DNA ladder and free DNA used as positive controls, respectively. A light band detected in Lane 3 is due to pDNA overloading. After filtering the pDNA-NPs suspension, the absence of a band in Lane 4 indicates full encapsulation of pDNA-NPs without free pDNA. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

The capacity of NPs to encapsulate pDNA was detected by gel electrophoresis. For better transfection efficacy, pDNA was overloaded to exceed the encapsulation capacity at a NP:pDNA ratio of 1:20. Therefore, free pDNA was detected (Fig. 1E, lane 3). However, after syringe filtering with a 100 um pore filter, unbound pDNA was not detected on the gel array (Fig. 1E, Lane 4), indicating no free pDNA in the nanosuspension.

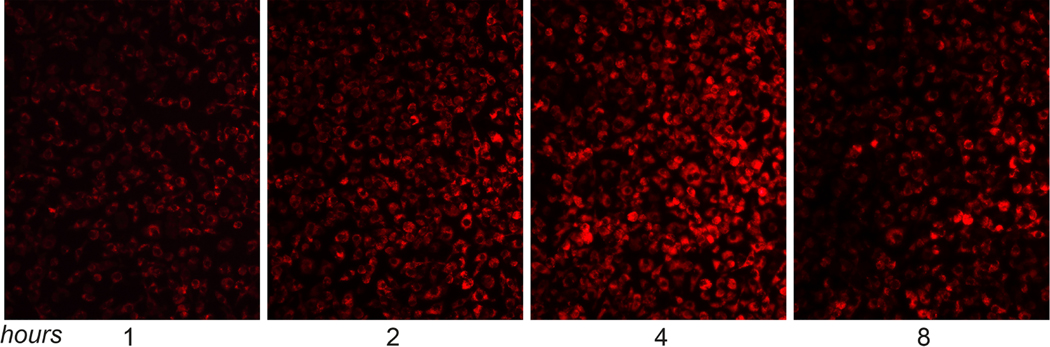

3.2. Uptake

In order to visualize pDNA-NP uptake by BMM, “red fluorescence” Rhodamine 6G was used to label NPs (rNPs). BMM were treated with pDNA-rNPs at a NPs/media ratio of 1:50 and incubated for 1, 2, 4 and 8 hours. The internalization of “red” pDNA-rNPs was determined by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2). At 1 hour, ~ 75% of BMM exhibited red fluorescence, indicating quick uptake of pDNA-rNPs by BMM. The internalization of pDNA-rNPs increased over time, with greater than 95% of cells exhibiting red fluorescence at 4 hours. Red fluorescence intensity decreased by 8 hours (Fig. 2). These results strongly indicate that BMM were capable of internalizing pDNA-NPs.

Fig. (2). Effective uptake of pDNA-NPs by BMM.

Fluorescent microscopy images of BMM treated with rhodamine-labeled pDNA-rNPs for 1, 2, 4 and 8 hours. Images showed that internalized pDNA-rNPs in BMM had an increase of “red” signals from 1 to 4 hours and were maintained up to 8 hours. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

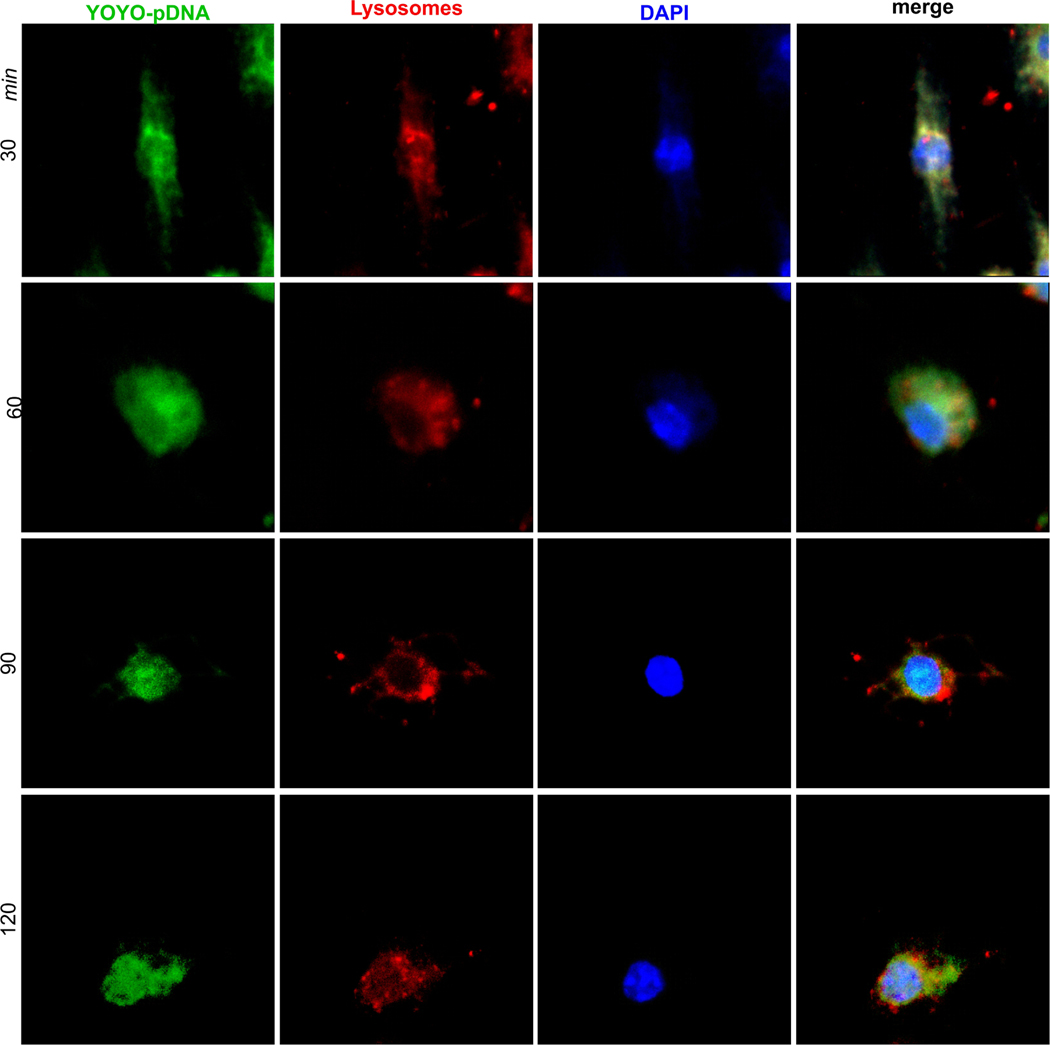

3.3. Cytoplasmic Transportation of pDNA-NPs

Dual labeling of pDNA with YOYO (YOYO-pDNA, green) and lysosomes with LysoTracker (red) allowed the visualization of time-dependent cytoplasmic transportation in BMM by fluorescence microscopy. The cultures were treated with YOYO-pDNA-NPs for 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes (Fig. 3, green). Lysosomes and nuclei were labeled with LysoTracker (Fig. 3, red) and DAPI (Fig. 3, blue), respectively. The images revealed “green” YOYO-pDNA-NPs were internalized by BMM at 30 minutes, and were immediately captured within “red” lysosomes, as indicated by “yellow” co-localization. Uptake of YOYO-pDNA-NPs by BMM continued, leading to an increase of “green” signals within the cytoplasm at 60 minutes. Separation of “green” YOYO-pDNA from “red” lysosomes occurred at 90 minutes and continued up to 120 minutes, showing the successful escape of YOYO-pDNA-NPs from lysosomes. YOYO-pDNA-NPs traversed into the “blue” nucleus at 90 minutes and were maintained up to 120 minutes.

Fig. (3). Internalization of IL-4pDNA-NPs and escape from lysosomes.

YOYO labeled pDNA (YOYO-pDNA, green) was loaded into NPs (YOYO-pDNA-NPs). BMM were treated with YOYO-pDNA-NPs for 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes, then the cultures were stained with LysoTracker and DAPI to label lysosomes (red) and the nucleus (blue). Confocal microscopy revealed the internalization of YOYO-pDNA-NPs, lysosomal escape and nuclear delivery. Images showed that “green” YOYO-pDNA-NPs were integrated with “red” lysosomes, exhibiting “yellow” co-localization at 30 minutes. YOYO-pDNA-NPs escaped from lysosomes resulting in the separation of “red” and “green” signals at 60 minutes. The escaped YOYO-pDNA-NPs (green) were transported into the nucleus (blue) at 90 and 120 minutes. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

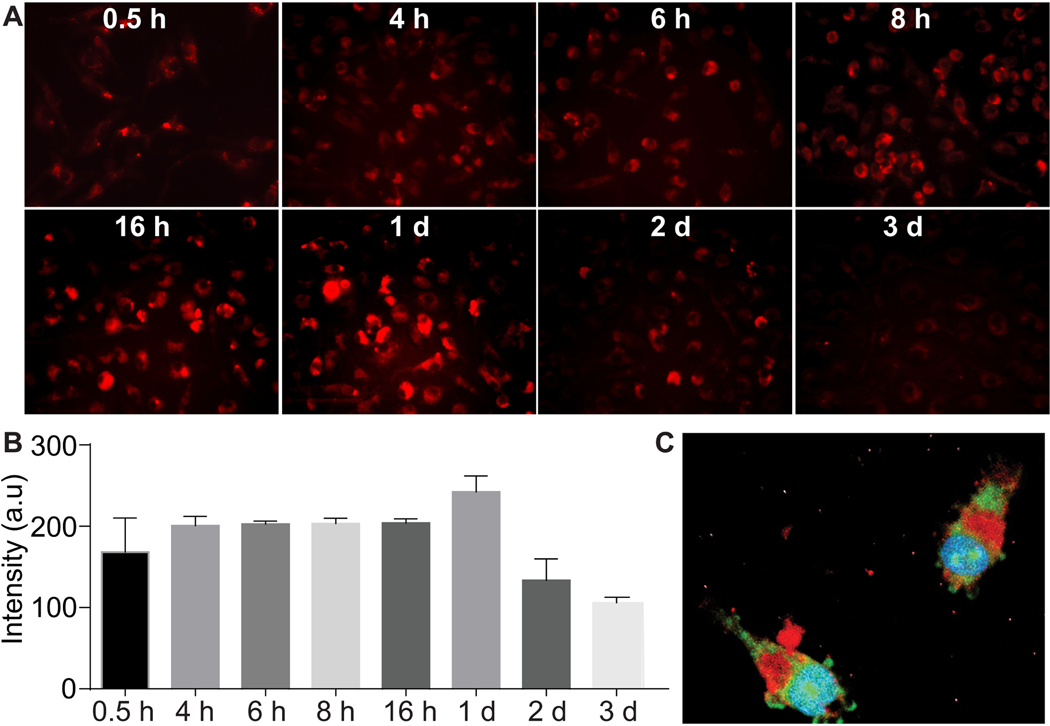

As a professional phagocyte, lysosomes in macrophages are largely activated during the uptake of “foreign” pDNA-NPs. We detected lysosomes responding to intracellular pDNA-NPs in BMM with time-dependent behavior (Fig. 4A). Quantification of images showed that lysosome activity increased in BMM up to 1 day after treating with pDNA-NPs (Fig. 4B), then gradually decreased over days 2 and 3. The representative image reveals the escape of YOYO-pDNA-NPs (Fig. 4C, green), leaving lysosomes (Fig. 4C, red) to enter the nucleus at 2 hours post-transfection. Nuclear translocation of YOYO-pDNA within 2 hours indicated that YOYO-pDNA-NPs can effectively cross the cytoplasmic membrane and the nuclear envelope to deliver pDNA by avoiding macrophage digestion and removal.

Fig. (4). Lysosome responses to pDNA-NPs.

BMM were treated with pDNA-NPs for 0.5, 4, 6, 8, and 16 hours, and 1, 2 and 3 days. Lysosomes were labeled with LysoTracker (A, red). The density of lysosomes increased after pDNA-NPs internalization. Quantitative analyses showed a gradual increase of lysosomal intensity up to 1 day, and then a reduction was seen at days 2 and 3 (B). Triple labeling of green YOYO-pDNA, red lysosomes and blue nucleus was performed in BMM treated with YOYO-pDNA-NPs for 4 hours (C). The image revealed the separation of YOYO-pDNA-NPs from lysosomes and the nuclear accumulation of YOYO-pDNA. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

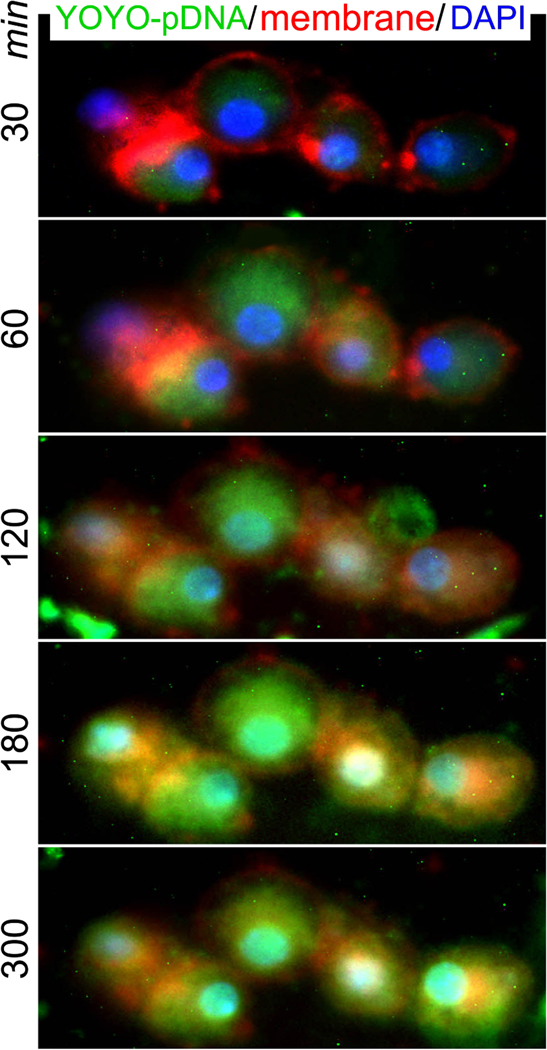

3.4. Real-time Live Cell Intracellular Trafficking and Nuclear Entry

Real-time live cell intracellular trafficking of pDNA-NPs was performed by fluorescence microscopy. Triple labeling of YOYO-pDNA loaded NPs (YOYO-pDNA-NPs; green), the cell membrane with dye CellBrite Fix555 (red) and the nucleus with DAPI (blue) was performed. The cultures were initially imaged 5 minutes after transfection followed by automatic scanning every 30 minutes. The representative images show that YOYO-pDNA-NPs (Fig. 5, green) crossed the cell membrane (Fig. 5, red) to remain within the cytoplasm at 30 minutes. The levels of YOYO-pDNA-NPs were consistently maintained inside of cells up to 300 minutes. The “green” YOYO-pDNA entered the “blue” nucleus at 120 minutes (Fig. 5, green-blue), while the nuclear accumulation of YOYO-pDNA was maintained up to 300 minutes. This finding suggests that the synthesized pDNA-NPs successfully crossed the cellular and nuclear membranes, and rapidly entered the nucleus without degradation.

Fig. (5). Nuclear delivery of YOYO-IL-4pDNA-NPs.

Live cell imaging was used to assess cytoplasmic transportation and the nuclear entrance of YOYO-pDNA-NPs. The cultures were treated with YOYO-pDNA-NPs (green) and the cell membrane and nucleus were labeled with CellBrite Fix 555 (red) and DAPI (blue), respectively. BMMs were automatically scanned every 30 minutes and continuously cultured under live cell fluorescence microscopy. The internalization of YOYO-pDNA (green) occurred at 30 minutes. At 120 minutes, “green” YOYO-pDNA were overlapped with “blue” nuclei. Consistent nuclear accumulation of YOYO-pDNA was seen at 180 and 300 minutes, exhibiting “cyan” nuclei. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

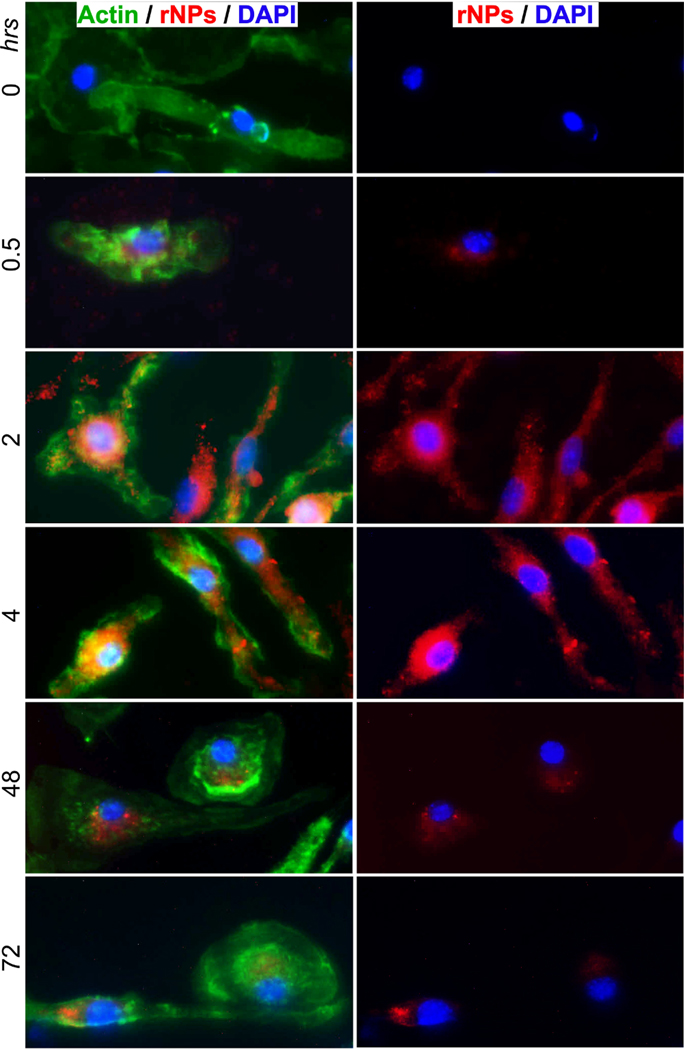

3.5. Intracellular Trafficking Mechanism of pDNA-NPs

To study cytoplasmic trafficking of pDNA-NPs, actin filaments were examined during the uptake of pDNA-rNPs by BMM. Changes in actin filaments were characterized at 0.5, 2, 4, 48 and 72 hours after treatment. Untreated BMM cells (0 hrs) served as the control. Control BMM displayed thin actin filaments throughout the cell with few small fragments (Fig. 6, green, 0 hrs). During active uptake of pDNA-rNPs, the increases of intracellular pDNA-rNPs (red) in BMM were co-localized with enlarged actin bundles at 0.5, 2 and 4 hours (Fig. 6, green) that is not seen in the control cells. Variable sizes and intensities of actin bundles were detected up to 48 hours. After 72 hours, intracellular levels of pDNA-rNPs decreased and actin bundles were also reduced concomitantly. The structure of actin observed at 72 hours was similar to the control. This suggests pDNA-rNPs interacted with the cytoskeletal network, inducing actin filament rearrangements to assist intracellular trafficking. The observed intracellular accumulation and nuclear entry of pDNA-NPs are most likely due to actin filament-mediated cytoplasmic trafficking.

Fig. (6). Actin filaments and pDNA-NPs intracellular trafficking.

BMM were treated with pDNA-rNPs (red) at 0.5, 2, 4, 48 and 72 hrs, and then the cultures were fixed and stained with an antibody to F-actin (green) and DAPI (blue). Untreated cells (0 hrs) served as the control. Triple labeling imaging was used to determine the responses of actin filaments to pDNA-rNPs internalization. Images showed the appearance of actin filaments (green) changing after uptake of pDNA-rNPs. BMM treated with pDNA-rNPs for 30 minutes induced actin filament bundles. Thick actin bundles were obtained at 24 hours after uptake. At 72 hours after BMM uptake, the actin filaments network resumed the appearance and distribution pattern observed at time point 0. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

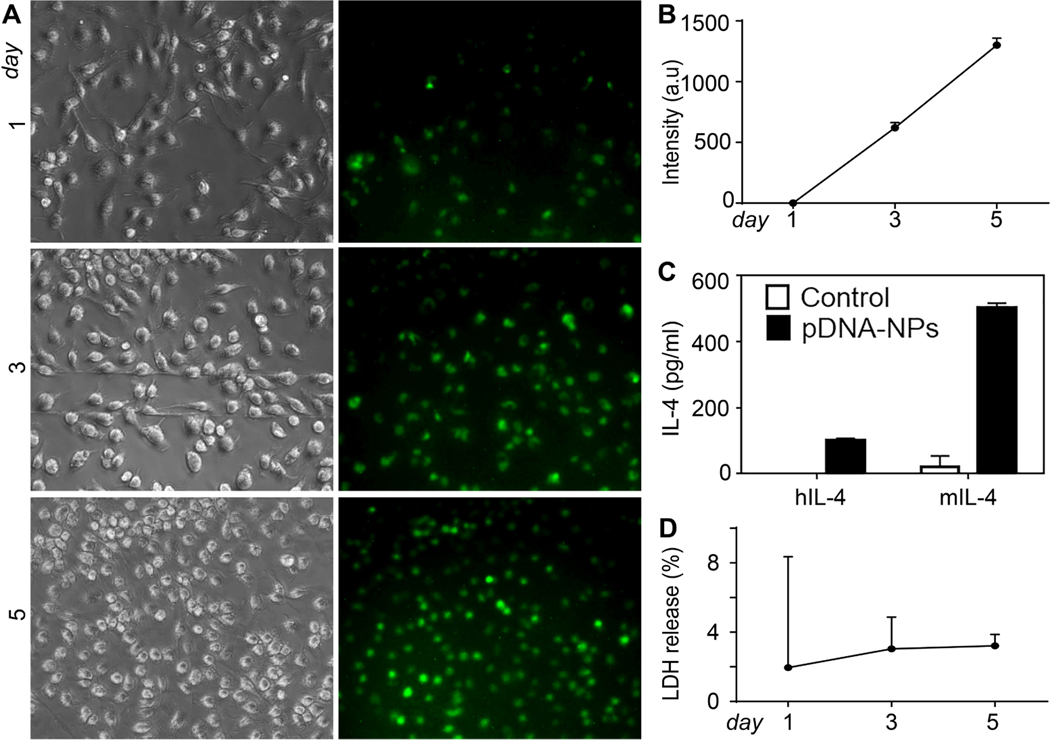

3.6. Transfection Efficacy of pDNA-NPs

Macrophages produce IL-4, a cytokine important for regulating macrophage polarization. Full-length human and mouse IL-4 pDNA tagged with GFP (IL-4pDNA/GFP) were loaded into NPs (IL-4pDNA/GFP-NPs) and transfected in BMM. The transfection efficiency was evaluated by measuring IL-4/GFP expression at days 1, 3 and 5. Notably, GFP expression was readily observed at 1 day. GFP expression increased at day 3 and peaked on day 5. (Fig. 7A). Quantification of green fluorescence confirms there is a significant increase in GFP expression in BMM from day 1 to day 5 (Fig. 7B). ELISA was used to determine the secretion of IL-4 in transfected mouse BMM (Fig. 7C). It is noteworthy that human IL-4 was detected from transfected mouse BMM, indicating the successful gene induction in BMM using IL-4pDNA/GFP-NPs. Cytotoxicity in BMM was analyzed by an LDH release assay (Fig. 7D). No toxicity was observed in BMM treated with IL-4pDNA/GFP-NPs compared to control. In summary, BMM treated with IL-4pDNA/GFP-NPs successfully expressed the IL-4 protein, suggesting that NPs could be used as an efficient gene delivery therapy in primary cells without toxicity.

Fig. (7). Exogenous IL-4 expression in IL-4pDNA/GFP-NPs treated BMM.

BMM were treated with IL-4pDNA/GFP-rNPs for 1, 3, and 5 days to evaluate GFP expression. GFP expression was observed at day 1 and increased at days 3 and 5 (A, green). Quantification of GFP+ intensity (B) confirmed the continual expression of IL-4/GFP in transfected BMM. BMM were treated with human IL-4pDNA/GFP and mouse IL-4pDNA/GFP loaded NPs for 5 days and an ELISA assay was used to determine human IL-4 and mouse IL-4 secretion from transfected BMM (C). Human specific IL-4 antibodies confirmed pDNA-NPs-mediated exogenous IL-4 expression. The secretion of human IL-4 from transfected mouse BMM strongly supports the successful gene delivery of pDNA-NPs in BMM. Cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release assay in BMM transfected with pDNA-NPs (D). (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

4. DISCUSSION

In a highly efficient gene delivery system, internalization, cytoplasmic transportation and nuclear delivery of pDNA are the most important factors [37, 41–43]. In phagocytes such as macrophages, it is much more challenging to protect the stability of both the carriers and genetic materials from endolysosomal digestion for the production of the desired gene outcome in these non-dividing cells. Our NPs synthesized from low MW branched PEI lipids have demonstrated effective transfection efficacy of pDNA in macrophages for gene-editing. In our previous work, we have found optimal conditions for the synthesis of the lipid from GHE and low MW branched PEI at a molar ratio of 8:1. Under this condition, PEI was fully modified by reacting with epoxy C16 of GHE. Since the PEI head group could react with the hexadecyl tail groups via a ring-opening reaction, it was facile to obtain high purity of the lipid.

Highly positive charged NPs are crucial for effective gene delivery [44–46]. The cationic PEI shell of NPs creates a positive zeta potential (56 mV) that can interact with negatively charged pDNA. Thus, when loaded with pDNA, the zeta potential of pDNA-NPs is lowered (~36 mV), reflecting the encapsulation of negatively charged materials. The overall positive charge of pDNA-NPs allows it to get proximal to the cell membrane and then internalized inside the cells.

The size of NPs was also found to play a major role in determining the efficiency of NP uptake by cells. In fact, our previous work showed a positive correlation between NP size (73 nm – 222 nm) and cellular uptake [19, 20]. NPs utilize multiple endocytic pathways to enter the cell. For example, NPs measuring a few hundred nanometers in diameter can enter the cell via pino- or micropinocytosis [47]. NPs with a size range of 120 – 150 nms are internalized via clathrin- or caveolin-mediated endocytosis, and the maximum size of NPs employing this pathway has been reported to be 200 nm [47, 93]. In the caveolae-mediated pathway, the size of caveolae hinders the uptake of larger NPs [16, 17]. Sizes over 250 nm to 3 μm are internalized by phagocytosis. Size-dependent uptake is also influenced by different types of cells [48–50]. Previous research showed that increasing NP size increased the uptake efficiency in human liver cancer cells. However, the increased NP size limited the uptake by normal human liver cells [48]. Finally, it is also important to consider the size of the nucleus (~1 μm to 10 μm) [51, 52] for optimal nuclear entry. We have determined in this study that NPs ~ 150 nm in size and pDNA-NPs approximately 200 nm would yield effective delivery in BMM cells.

In order to understand the mechanisms of uptake and cytoplasmic trafficking, we performed triple labeling assays for NPs, pDNA, and cell organelles to visualize their internalization and transportation. We found that pDNA-NPs were internalized within 30 minutes. The YOYO-pDNA entered the nucleus within 1 hour and the delivery of pDNA resulted in the desired gene expression in BMM. While NP internalization can integrate with lysosomes for the breakdown of trapped NPs [53–56], our pDNA-NPs were able to escape this pathway and translocate into the cytoplasm and subsequently into the nucleus [19]. This is noteworthy as the commercially available carrier lipofectamine cannot transfect BMM, and PEI25K [57] cannot achieve high transfection efficiency in BMM [19]. In addition to bypassing lysosomal degradation, our findings suggest that pDNA-NPs trafficking in BMM cells was mediated by actin filaments. Image analysis of actin filaments shows pDNA-NPs stimulated rearrangement of actin filaments into bundles after internalization. These bundles then depolymerized back into filaments at 72 hours, consistent with the breakdown of NPs after nuclear delivery of pDNA. Importantly, our data show that the uptake of pDNA-NPs by BMM and the subsequent structural changes in the actin network did not trigger degradation or apoptotic pathways [58, 59]. In fact, images (Fig. 6) reveal active changes in actin filaments during pDNA-rNPs uptake by BMM (0 to 4 hours), intracellular transportation (2 to 48 hours) and degradation (72 hours). Once pDNA-NPs were degraded, actin filaments resumed a thin filamentous phenotype as observed in the control. This suggests a dynamic movement of intracellular NPs closely associated with the actin filament network.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our findings have shown that in phagocytic cells, our pDNA-NPs system can escape lysosomal digestion, maintain stability, and can successfully deliver human IL-4 pDNA into the mouse BMM genome to produce functional human IL-4 protein. The internalization of our pDNA-NPs system into BMM cells led to dynamic changes in actin filaments, mediating effective intracellular trafficking for nuclear delivery. Importantly, our pDNA-NP carrier did not trigger intracellular degradation responses, and did not cause cytotoxicity as seen with traditional PEI carriers. Hence, core-shell NPs loaded with target pDNA can be a potential alternative for effective gene delivery in many cell types, especially non-dividing cells such as macrophages. Further studies should explore its potential in in vitro and in vivo assays for translation into clinical applications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully thank the staff of the Core Facility at TTUHSC El Paso for their help in using the Confocal and Electron Microscopes, and the staff of the Laboratory Animal Resource Center for their help in animal maintenance and care.

FUNDING

This study was supported by NIH 1R01GM114851 and NIH 5R01DK117383, and the Seed Grant of Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso.

Footnotes

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This research was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles. All experiments in Balb/C mice were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

DISCLAIMER: The above article has been published in Epub (ahead of print) on the basis of the materials provided by the author. The Editorial Department reserves the right to make minor modifications for further improvement of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Some of the authors have pending patent applications related to the present study: “High Efficient Delivery of Plasmid DNA into Human and Vertebrate Primary Cells in vitro and in vivo by Nanocomplexes” filed by Texas Tech University. EFS ID: 39781879 with application #:16956627, International Application No. PCT/US2018/063546 and Application number WO2019/133190.

REFERENCES

- [1].Koppu S, Oh YJ, Edrada-Ebel R, et al. Tumor regression after systemic administration of a novel tumor-targeted gene delivery system carrying a therapeutic plasmid DNA. J Control Release 2010; 143(2): 215–21. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.11.015 PMID: 19944722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lu Y, Jiang W, Wu X, et al. Peptide T7-modified polypeptide with disulfide bonds for targeted delivery of plasmid DNA for gene therapy of prostate cancer. Int J Nanomedicine 2018; 13: 6913–27. 10.2147/IJN.S180957 PMID: 30464450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Scholz C, Wagner E. Therapeutic plasmid DNA versus siRNA delivery: common and different tasks for synthetic carriers. J Control Release 2012; 161(2): 554–65. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.11.014 PMID: 22123560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang Y, Li X, Liu L, Liu B, Wang F, Chen C. Tissue Targeting and Ultrasound-Targeted Microbubble Destruction Delivery of Plasmid DNA and Transfection In Vitro. Cell Mol Bioeng 2019; 13(1): 99–112. 10.1007/s12195-019-00597-w PMID: 32030111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Siu YS, Li L, Leung MF, Lee KL, Li P. Polyethylenimine-based amphiphilic core-shell nanoparticles: study of gene delivery and intracellular trafficking. Biointerphases 2012; 7(1–4): 16. 10.1007/s13758-011-0016-4 PMID: 22589059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Aissaoui A, Chami M, Hussein M, Miller AD. Efficient topical delivery of plasmid DNA to lung in vivo mediated by putative triggered, PEGylated pDNA nanoparticles. J Control Release 2011; 154(3): 275–84. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.017 PMID: 21699935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Park YM, Shin BA, Oh IJ. Poly(L-lactic acid)/polyethylenimine nanoparticles as plasmid DNA carriers. Arch Pharm Res 2008; 31(1): 96–102. 10.1007/s12272-008-1126-5 PMID: 18277614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sato A, Kawakami S, Yamada M, Yamashita F, Hashida M. Enhanced gene transfection in macrophages using mannosylated cationic liposome-polyethylenimine-plasmid DNA complexes. J Drug Target 2001; 9(3): 201–7. 10.3109/10611860108997928 PMID: 11697205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Farrell LL, Pepin J, Kucharski C, Lin X, Xu Z, Uludag H. A comparison of the effectiveness of cationic polymers poly-L-lysine (PLL) and polyethylenimine (PEI) for non-viral delivery of plasmid DNA to bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC). Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2007; 65(3): 388–97. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.11.026 PMID: 17240127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Liu XY, Ho WY, Hung WJ, Shau MD. The characteristics and transfection efficiency of cationic poly (ester-co-urethane) - short chain PEI conjugates self-assembled with DNA. Biomaterials 2009; 30(34): 6665–73. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.052 PMID: 19775745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Díaz-Moscoso A, Le Gourriérec L, Gómez-García M, et al. Polycationic amphiphilic cyclodextrins for gene delivery: synthesis and effect of structural modifications on plasmid DNA complex stability, cytotoxicity, and gene expression. Chemistry 2009; 15(46): 12871–88. 10.1002/chem.200901149 PMID: 19834934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kodama Y, Noda R, Sato K, et al. Methotrexate-Coated Complexes of Plasmid DNA and Polyethylenimine for Gene Delivery. Biol Pharm Bull 2018; 41(10): 1537–42. 10.1248/bpb.b18-00144 PMID: 30270323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liu H, Yang Z, Xun Z, et al. Nuclear delivery of plasmid DNA determines the efficiency of gene expression. Cell Biol Int 2019; 43(7): 789–98. 10.1002/cbin.11155 PMID: 31042002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Briane D, Lesage D, Cao A, et al. Cellular pathway of plasmids vectorized by cholesterol-based cationic liposomes. J Histochem Cytochem 2002; 50(7): 983–91. 10.1177/002215540205000712 PMID: 12070277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cohen RN, van der Aa MA, Macaraeg N, Lee AP, Szoka FC Jr. Quantification of plasmid DNA copies in the nucleus after lipoplex and polyplex transfection. J Control Release 2009; 135(2): 166–74. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.12.016 PMID: 19211029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kwak SY, Han HD, Ahn HJA. A T7 autogene-based hybrid mRNA/DNA system for long-term shRNA expression in cytoplasm without inefficient nuclear entry. Sci Rep 2019; 9(1): 2993. 10.1038/s41598-019-39407-8 PMID: 30816180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Davies LA, Hyde SC, Nunez-Alonso G, et al. The use of CpGfree plasmids to mediate persistent gene expression following repeated aerosol delivery of pDNA/PEI complexes. Biomaterials 2012; 33(22): 5618–27. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.019 PMID:22575838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Deng W, Xiao H, Zeng X, Hu Y. MC8 peptide-mediated Her-2 receptor targeting based on PEI-β-CyD as gene delivery vector. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2013; 169(2): 450–61. 10.1007/s12010-012-9959-2 PMID: 23225019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zou L, Lee SY, Wu Q, et al. Facile Gene Delivery Derived from Branched Low Molecular Weight Polyethylenimine by High Efficient Chemistry. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2018; 14(10): 1785–95. 10.1166/jbn.2018.2620 PMID: 30041724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zou L Macias sustaita A; Thomas Tima; Do L; Rodriguez J; Dou H. Size Effects of Nanocomplex on Tumor Associated Macrophages Targeted Delivery for Glioma. J Nanomed Nanotechnol 2015; 6(6): 3–10. 10.4172/2157-7439.1000339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zou L, Tao Y, Payne G, et al. Targeted delivery of nano-PTX to the brain tumor-associated macrophages. Oncotarget 2017; 8(4): 6564–78. 10.18632/oncotarget.14169 PMID: 28036254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Burke B, Sumner S, Maitland N, Lewis CE. Macrophages in gene therapy: cellular delivery vehicles and in vivo targets. J Leukoc Biol 2002; 72(3): 417–28. PMID: 12223508 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Broeders M, Herrero-Hernandez P, Ernst MPT, van der Ploeg AT, Pijnappel W. Sharpening the Molecular Scissors: Advances in Gene-Editing Technology. iScience 2020; 23(1): 100789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tu K, Deng H, Kong L, et al. Reshaping Tumor Immune Microenvironment through Acidity-Responsive Nanoparticles Featured with CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Attenuation and Chemotherapeutics-Induced Immunogenic Cell Death. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020; 12(14): 16018–30. 10.1021/acsami.9b23084 PMID: 32192326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tan B, Shi X, Zhang J, et al. Inhibition of Rspo-Lgr4 Facilitates Checkpoint Blockade Therapy by Switching Macrophage Polarization. Cancer Res 2018; 78(17): 4929–42. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0152 PMID:29967265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Alam MM, O’Neill LA. MicroRNAs and the resolution phase of inflammation in macrophages. Eur J Immunol 2011; 41(9):2482–5. 10.1002/eji.201141740 PMID: 21952801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jackaman C, Radley-Crabb HG, Soffe Z, Shavlakadze T, Grounds MD, Nelson DJ. Targeting macrophages rescues age-related immune deficiencies in C57BL/6J geriatric mice. Aging Cell 2013; 12(3): 345–57. 10.1111/acel.12062 PMID: 23442123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Xia W, Zou C, Chen H, Xie C, Hou M. Immune checkpoint inhibitor induces cardiac injury through polarizing macrophages via modulating microRNA-34a/Kruppel-like factor 4 signaling. Cell Death Dis 2020; 11(7): 575. 10.1038/s41419-020-02778-2 PMID: 32709878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tuohy JL, Somarelli JA, Borst LB, Eward WC, Lascelles BDX, Fogle JE. Immune dysregulation and osteosarcoma: Staphylococcus aureus downregulates TGF-β and heightens the inflammatory signature in human and canine macrophages suppressed by osteosarcoma. Vet Comp Oncol 2020; 18(1): 64–75. 10.1111/vco.12529 PMID: 31420936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Parayath NN, Parikh A, Amiji MM. Repolarization of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in a Genetically Engineered Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer Model by Intraperitoneal Administration of Hyaluronic Acid-Based Nanoparticles Encapsulating MicroRNA-125b. Nano Lett 2018; 18(6): 3571–9. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b00689 PMID: 29722542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chen Q, Qi R, Chen X, et al. Polymeric Nanostructure Compiled with Multifunctional Components To Exert Tumor-Targeted Delivery of Antiangiogenic Gene for Tumor Growth Suppression. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016; 8(37): 24404–14. 10.1021/acsami.6b06782 PMID: 27576084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jain N, Arntz Y, Goldschmidt V, Duportail G, Mély Y, Klymchenko AS. New unsymmetrical bolaamphiphiles: synthesis, assembly with DNA, and application for gene delivery. Bioconjug Chem 2010; 21(11): 2110–8. 10.1021/bc100334t PMID: 20945885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Patil S, Gao YG, Lin X, et al. The Development of Functional Non-Viral Vectors for Gene Delivery. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20(21): E5491. 10.3390/ijms20215491 PMID: 31690044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Panão Costa J, Carvalho S, Jesus S, Soares E, Marques AP, Borges O. Optimization of Chitosan-α-casein Nanoparticles for Improved Gene Delivery: Characterization, Stability, and Transfection Efficiency. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019; 20(3): 132. 10.1208/s12249-019-1342-y PMID: 30820699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Nazari M, Zamani Koukhaloo S, Mousavi S, Minai-Tehrani A, Emamzadeh R, Cheraghi R. Development of a ZHER3-Affibody--Targeted Nano-Vector for Gene Delivery to HER3-Overexpressed Breast Cancer Cells. Macromol Biosci 2019; 19(11): e1900159. 10.1002/mabi.201900159 PMID: 31531954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liufu C, Li Y, Tu J, et al. Echogenic PEGylated PEI-Loaded Microbubble As Efficient Gene Delivery System. Int J Nanomedicine 2019; 14: 8923–41. 10.2147/IJN.S217338 PMID: 31814720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pozzi D, Marchini C, Cardarelli F, et al. Mechanistic evaluation of the transfection barriers involved in lipid-mediated gene delivery: interplay between nanostructure and composition. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1838(3): 957–67. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.11.014 PMID:24296066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Trigueros S, Domènech EB, Toulis V, Marfany G. In Vitro Gene Delivery in Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cells by Plasmid DNA-Wrapped Gold Nanoparticles. Genes (Basel) 2019; 10(4): E289. 10.3390/genes10040289 PMID: 30970664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Freitas S, Merkle HP, Gander B. Microencapsulation by solvent extraction/evaporation: reviewing the state of the art of microsphere preparation process technology. J Control Release 2005;102(2): 313–32. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.015 PMID: 15653154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wong M, Kong S, Dragowska WH, Bally MB. Oxazole yellow homodimer YOYO-1-labeled DNA: a fluorescent complex that can be used to assess structural changes in DNA following formation and cellular delivery of cationic lipid DNA complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2001; 1527(1–2): 61–72. 10.1016/S0304-4165(01)00149-0 PMID: 11420144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zheng Y, Song X, He G, et al. Receptor-mediated gene delivery by folate-poly(ethylene glycol)-grafted-trimethyl chitosan in vitro. J Drug Target 2011; 19(8): 647–56. 10.3109/1061186X.2010.525650 PMID:20964597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].He Y, Zhou J, Ma S, et al. Multi-Responsive “Turn-On” Nanocarriers for Efficient Site-Specific Gene Delivery In Vitro and In Vivo. Adv Healthc Mater 2016; 5(21): 2799–812. 10.1002/adhm.201600710 PMID: 27717282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li LM, Ruan GX, HuangFu MY, et al. ScreenFect A: an efficient and low toxic liposome for gene delivery to mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Pharm 2015; 488(1–2): 1–11. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.04.050 PMID: 25895721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Khalil IA, Kimura S, Sato Y, Harashima H. Synergism between a cell penetrating peptide and a pH-sensitive cationic lipid in efficient gene delivery based on double-coated nanoparticles. J Control Release 2018; 275: 107–16. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.02.016 PMID: 29452131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Liu Z, Niu D, Zhang J, et al. Amphiphilic core-shell nanoparticles containing dense polyethyleneimine shells for efficient delivery of microRNA to Kupffer cells. Int J Nanomedicine 2016; 11: 2785–97. PMID: 27366061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Yi SW, Park JS, Kim HJ, Lee JS, Woo DG, Park KH. Multiply clustered gold-based nanoparticles complexed with exogenous pDNA achieve prolonged gene expression in stem cells. Theranostics 2019; 9(17): 5009–19. 10.7150/thno.34487 PMID: 31410198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Behzadi S, Serpooshan V, Tao W, et al. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: journey inside the cell. Chem Soc Rev 2017; 46(14): 4218–44. 10.1039/C6CS00636A PMID: 28585944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Xia Q, Huang J, Feng Q, et al. Size- and cell type-dependent cellular uptake, cytotoxicity and in vivo distribution of gold nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine 2019; 14: 6957–70. 10.2147/IJN.S214008 PMID: 32021157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cheng X, Tian X, Wu A, et al. Protein Corona Influences Cellular Uptake of Gold Nanoparticles by Phagocytic and Nonphagocytic Cells in a Size-Dependent Manner. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015; 7(37): 20568–75. 10.1021/acsami.5b04290 PMID: 26364560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kim IY, Joachim E, Choi H, Kim K. Toxicity of silica nanoparticles depends on size, dose, and cell type. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2015; 11(6): 1407–16. 10.1016/j.nano.2015.03.004 PMID: 25819884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mourant JR, Johnson TM, Carpenter S, Guerra A, Aida T, Freyer JP. Polarized angular dependent spectroscopy of epithelial cells and epithelial cell nuclei to determine the size scale of scattering structures. J Biomed Opt 2002; 7(3): 378–87. 10.1117/1.1483317 PMID: 12175287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Parsons DF, Cole RW, Kimelberg HK. Shape, size, and distribution of cell structures by 3-D graphics reconstruction and stereology. I. The regulatory volume decrease of astroglial cells. Cell Biophys 1989; 14(1): 27–42. 10.1007/BF02797389 PMID: 2465084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cui Y, Shan W, Zhou R, et al. The combination of endolysosomal escape and basolateral stimulation to overcome the difficulties of “easy uptake hard transcytosis” of ligand-modified nanoparticles in oral drug delivery. Nanoscale 2018; 10(3): 1494–507. 10.1039/C7NR06063G PMID: 29303184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Deville S, Penjweini R, Smisdom N, et al. Intracellular dynamics and fate of polystyrene nanoparticles in A549 Lung epithelial cells monitored by image (cross-) correlation spectroscopy and single particle tracking. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015; 1853 (10 Pt A): 2411–9. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.07.004 PMID: 26164626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jimeno-Romero A, Izagirre U, Gilliland D, et al. Lysosomal responses to different gold forms (nanoparticles, aqueous, bulk) in mussel digestive cells: a trade-off between the toxicity of the capping agent and form, size and exposure concentration. Nanotoxicology 2017; 11(5): 658–70. 10.1080/17435390.2017.1342012 PMID:28758565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sun X, Cheng C, Zhang J, et al. Intracellular Trafficking Network and Autophagy of PHBHHx Nanoparticles and their Implications for Drug Delivery. Sci Rep 2019; 9(1): 9585. 10.1038/s41598-019-45632-y PMID: 31270337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Boussif O, Lezoualc’h F, Zanta MA, et al. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92(16):7297–301. 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297 PMID: 7638184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Liu P, Sun Y, Wang Q, Sun Y, Li H, Duan Y. Intracellular trafficking and cellular uptake mechanism of mPEG-PLGA-PLL and mPEG-PLGA-PLL-Gal nanoparticles for targeted delivery to hepatomas. Biomaterials 2014; 35(2): 760–70. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.020 PMID:24148242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Peñaloza JP, Márquez-Miranda V, Cabaña-Brunod M, et al. Intracellular trafficking and cellular uptake mechanism of PHBV nanoparticles for targeted delivery in epithelial cell lines. J Nanobiotechnology 2017; 15(1): 1. 10.1186/s12951-016-0241-6 PMID: 28049488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]