Abstract

BACKGROUND

The impact of utilization of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) at the time of isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) on clinical decision making and associated outcomes is not well understood.

OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this study was to determine the association of TEE with post-CABG mortality and changes to the operative plan.

METHODS

A retrospective cohort study of planned isolated CABG patients from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database between January 1, 2011, and June 30, 2019, was performed. The exposure variable of interest was use of intraoperative TEE during CABG compared with no TEE. The primary outcome was operative mortality. The association of TEE with unplanned valve surgery was also assessed.

RESULTS

Of 1,255,860 planned isolated CABG procedures across 1218 centers, 676,803 (53.9%) had intraoperative TEE. The proportion of patients receiving intraoperative TEE increased over time from 39.9% in 2011 to 62.1% in 2019 (p trend <0.0001). CABG patients undergoing intraoperative TEE had lower odds of mortality (adjusted odds ratio: 0.95; 95% confidence interval: 0.91 to 0.99; p = 0.025), with heterogeneity across STS risk groups (p interaction = 0.015). TEE was associated with increased odds of unplanned valve procedure in lieu of planned isolated CABG (adjusted odds ratio: 4.98; 95% confidence interval: 3.98 to 6.22; p < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

Intraoperative TEE usage during planned isolated CABG is associated with lower operative mortality, particularly in higher-risk patients, as well as greater odds of unplanned valve procedure. These findings support usage of TEE to improve outcomes for isolated CABG for high-risk patients.

Keywords: cardiac surgery, coronary artery bypass grafting, echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography

Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is an important diagnostic modality in cardiac surgical care (1-5). TEE provides real-time assessment of cardiac structure and function—including regional wall motion analysis, systolic and diastolic function, and native and prosthetic valve function (3). Intraoperative TEE has the potential to reinforce or improve upon pre-operative diagnosis (6), guide the conduct of the operation and cardiopulmonary bypass management (7), and confirm optimal cardiac function prior to transfer of care to the intensive care unit (ICU) (8,9). Intraoperative TEE is also safe with a low complication rate (10,11).

Guidelines recommend that intraoperative TEE be utilized “in all open heart (e.g., valvular procedures) and thoracic aortic surgical procedures and should be considered in coronary artery bypass graft surgeries” (2). Although endorsed by guidelines (2-4) with a Class IIa, Level of Evidence B recommendation, the evidence base for intraoperative TEE is sparse. Prior studies have largely focused solely on whether TEE changed the operative plan (12-17) rather than whether TEE improved clinical outcomes. Studies that have assessed outcomes have been small and underpowered (18), or solely relied on claims data with varied conclusions (19-21).

There are several knowledge gaps regarding use of intraoperative TEE for isolated CABG. First, the proportion of CABG procedures nationwide that incorporate TEE is unknown. This knowledge is important to identify practice patterns, forecast training needs, and identify potential disparities in intraoperative imaging. Second, patient- and institution-specific factors associated with use of intraoperative TEE are not known. This knowledge could identify targets for expanded use of intraoperative imaging. Finally, and most impactfully, it remains unclear whether intraoperative TEE in CABG is indeed associated with improved clinical outcomes (22).

We therefore performed a retrospective cohort study of TEE use in planned isolated CABG patients using data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery Database (ACSD). We hypothesized that TEE use would be variable across the United States and associated with improved clinical outcomes.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION.

The initial study population from the STS ACSD included 1,280,538 isolated CABG patients across 1,222 centers. Missing information on use or nonuse of TEE occurred in 24,678 cases who were excluded. The final study cohort included 1,255,860 isolated CABG procedures across 1,218 centers (Supplemental Figure 1). To determine whether TEE was associated with unplanned valve procedure, the population was restricted to those patients with refined procedural data elements in STS ACSD versions 2.81 and 2.9. For this analysis, we modified the STS ACSD’s definition of isolated CABG to allow unplanned valves into the cohort, resulting in 840,253 isolated CABG allowing unplanned valve procedures. Of these, 7,631 were missing TEE information and 1,156 missing unplanned valve operation, leaving 831,528 cases between July 1, 2014, and September 30, 2019 (Supplemental Figure 1). The Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board (Pro00014556) deemed individual STS analyses exempt from institutional review board review.

EXPOSURE.

The exposure variable of interest was use of intraoperative TEE during CABG, which is defined as any intraoperative TEE usage.

OUTCOMES.

The primary outcome was operative mortality. Operative mortality is defined in all STS databases as: 1) all deaths, regardless of cause, occurring during the hospitalization in which the operation was performed, even if after 30 days, including patients transferred to other acute care facilities; and 2) all deaths, regardless of cause, occurring after discharge from the hospital, but before the end of the 30th postoperative day (23). The secondary outcome was the association of TEE usage with an outcome of unplanned valve surgery due to unsuspected patient disease or anatomy. Other secondary outcomes included post-operative renal failure, post-operative prolonged mechanical ventilation >24 h, post-operative prolonged ICU stay >2 days, reoperation, and hospital readmission within 30 days.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

We compared patient characteristics across TEE usage with counts and percentage for categorical variables and median and interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles) for continuous variables. Comparisons were made using chi-square and Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate. Changes in TEE usage over time were assessed by the Cochran-Armitage trend test. We used logistic regression to determine clinical, demographic, and center factors associated with TEE usage. Models were adjusted for factors defined a priori based on their previously known or suspected associations with TEE usage and clinical outcomes. These factors include patient demographics and comorbidities as well as center factors, including region, teaching hospital status, and hospital volume, and are listed in the Supplemental Table 1. We accounted for center-level variation using generalized estimating equations with an independent working correlation.

To determine the association of TEE usage with outcomes, we performed a propensity-matched analysis to account for baseline differences. Propensity scores representing the probability of having intraoperative TEE were estimated by logistic regression using the variables in Supplemental Table 1 from the CABG risk model. TEE and non-TEE cases with similar propensity scores were then matched 1:1 by a greedy matching algorithm. Covariate balance was assessed by plotting standardized differences before and after matching; after matching, covariate balance was acceptable with all standardized differences <10% (Supplemental Figure 2). We proceeded to perform logistic regression models to examine the association of TEE versus no TEE usage with outcomes. Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated in the propensity matched cohort and doubly robust adjustment was performed using covariates in Supplemental Table 1 to account for minor residual covariate imbalances after propensity matching. To determine if patient risk was an effect measure modifier of the relationship between TEE usage and outcome, we stratified by STS predicted risk into 3 risk groups: low (<4%), moderate (4% to 8%), or high (>8%) risk of operative mortality.

To address the potential confounder that valvular disease could be discovered pre-operatively differentially on the basis of TEE use, we performed a sensitivity analysis, recalculating propensity scores excluding all valvular heart disease (MR, TR, AS, AI) for the primary outcome of mortality and outcome of unplanned valve procedure and removing valve disease as a covariate.

Analyses were performed at the STS Data Coordinating Center at the Duke Clinical Research Institute. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

UTILIZATION OF TEE DURING CABG.

Of 1,255,860 isolated CABG procedures across 1,218 centers, 676,803 (53.9%) had intraoperative TEE as part of their CABG procedure. The proportion of isolated CABG patients receiving intraoperative TEE varied across centers (Central Illustration). The percentage of isolated CABG patients receiving TEE increased over time from 39.9% in 2011 to 62.1% in 2019 (p < 0.0001 for trend) (Central Illustration). There was no association between a site’s CABG volume and TEE use (p = 0.48) (Supplemental Figure 3).

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Utilization and Outcomes of Intraoperative Transesophageal Echocardiography at the Time of Isolated Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting.

(A) The proportion of isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) patients receiving intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) at each of 1,218 centers across the United States, rank ordered by proportion per center. (B) Proportion of isolated CABG procedures per year receiving intraoperative TEE. p < 0.0001 for increasing trend over time. (C) Using data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database, intraoperative TEE as time of isolated CABG was associated with lower operative mortality, particularly among patients at greatest operative risk as well as increased likelihood of unplanned valve procedure in lieu of planned isolated CABG.

Demographic, clinical, and site characteristics of TEE and non-TEE patients are shown in Table 1. Patients receiving TEE had a greater risk profile with higher rates of chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart failure, myocardial infarction, shock, arrhythmia, and valvular heart disease (p < 0.0001 for all). Operative characteristics are shown in Table 1. TEE use was more common in patients with ACS on presentation, in emergent and urgent cases, and associated with a higher rate of intraoperative mechanical circulatory support (p < 0.0001 for all). Factors associated with intra-operative TEE usage are shown in Supplemental Table 2. After multivariable adjustment, Medicare insurance, urgent and emergent clinical status, lower left ventricular ejection fraction, and known valve disease of moderate or greater severity were associated with greater odds of TEE usage. Hospitals in the South and Midwest were less likely to use intraoperative TEE compared with Northeastern hospitals. Teaching hospitals had nearly 2-fold odds of TEE usage compared with nonteaching hospitals (OR: 1.97; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.38 to 2.81; p = 0.0002).

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of CABG Patients Who Received Intraoperative TEE Versus Non-TEE Patients

| Overall (N = 1,255,860) | No TEE (n = 579,057) | TEE (n = 676,803) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 66.0 (58.0-73.0) | 66.0 (58.0-73.0) | 66.0 (59.0-73.0) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 24,298 (1.97) | 9,628 (1.69) | 14,670 (2.21) |

| Black | 6,430 (0.52) | 3,129 (0.55) | 3,301 (0.5) |

| Hispanic | 40,020 (3.25) | 14,784 (2.6) | 25,236 (3.81) |

| Native American | 86,760 (7.04) | 34,976 (6.14) | 51,784 (7.82) |

| Other | 93,192 (7.57) | 42,379 (7.45) | 50,813 (7.67) |

| White | 980,966 (79.65) | 464,316 (81.57) | 516,650 (77.99) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.2 (25.9-33.2) | 29.3 (25.9-33.3) | 29.1 (25.9-33.2) |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 603,707 (48.14) | 272,881 (47.18) | 330,826 (48.96) |

| History of hypertension | 1,116,851 (89.05) | 512,862 (88.66) | 603,989 (89.38) |

| Current renal failure requiring dialysis | 37,834 (3.02) | 15,625 (2.7) | 22,209 (3.29) |

| History of dyslipidemia | 1,111,848 (88.73) | 509,214 (88.12) | 602,634 (89.26) |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 37,795 (3.02) | 16,086 (2.78) | 21,709 (3.22) |

| History of peripheral vascular disease | 176,049 (14.07) | 79,366 (13.74) | 96,683 (14.35) |

| Home oxygen | 21,042 (1.69) | 9,291 (1.61) | 11,751 (1.75) |

| Liver disease | 35,596 (2.86) | 15,179 (2.64) | 20,417 (3.04) |

| ADP inhibitors within 5 days | 134,871 (10.78) | 62,208 (10.77) | 72,663 (10.79) |

| Beta blockers | 1,122,606 (89.43) | 514,460 (88.87) | 608,146 (89.91) |

| Inotropic agents | 17,216 (1.37) | 7,345 (1.27) | 9,871 (1.46) |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs within 48 h | 531,262 (42.56) | 251,121 (43.56) | 280,141 (41.69) |

| Anticoagulants | 535,605 (42.75) | 234,756 (40.57) | 300,849 (44.61) |

| Aspirin | 1,051,161 (84.15) | 479,365 (83.1) | 571,796 (85.05) |

| Lipid lowering | 984,265 (78.84) | 445,997 (77.37) | 538,268 (80.1) |

| Congestive heart failure | 219,707 (17.66) | 92,698 (16.15) | 127,009 (18.96) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 20,611 (1.64) | 8,576 (1.48) | 12,035 (1.78) |

| Arrhythmia | 106,291 (8.49) | 45,047 (7.8) | 61,244 (9.08) |

| Hospital teaching status | 159,111 (12.67) | 51,601 (8.91) | 107,510 (15.88) |

| History of chronic lung disease | |||

| Lung disease, unknown severity | 51,184 (4.15) | 21,663 (3.81) | 29,521 (4.45) |

| Severe | 53,477 (4.34) | 23,305 (4.1) | 30,172 (4.55) |

| Moderate | 65,305 (5.3) | 29,977 (5.27) | 35,328 (5.32) |

| Mild | 142,363 (11.55) | 65,328 (11.48) | 77,035 (11.61) |

| No | 920,257 (74.66) | 428,746 (75.35) | 491,511 (74.07) |

| Pre-operative creatinine | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

| Smoking history | |||

| Current smoker | 282,118 (22.55) | 132,627 (22.98) | 149,491 (22.18) |

| Past smoker | 367,302 (29.36) | 157,416 (27.27) | 209,886 (31.14) |

| Never smoker | 601,813 (48.1) | 287,125 (49.75) | 314,688 (46.69) |

| Pre-operative left ventricular ejection fraction | 55.0 (45.0-60.0) | 55.0 (45.0-60.0) | 55.0 (45.0-60.0) |

| ≥50% | 838,610 (68.69) | 397,431 (70.89) | 441,179 (66.81) |

| ≥30% and <50% | 306,190 (23.81) | 133,500 (23.81) | 172,690 (26.15) |

| <30% | 76,135 (6.24) | 29,679 (5.29) | 46,456 (7.04) |

| Myocardial infarction | |||

| ≤6 h | 16,717 (1.34) | 7,807 (1.35) | 8,910 (1.32) |

| 6-24 h | 29,778 (2.38) | 13,703 (2.38) | 16,075 (2.39) |

| 1-7 days | 320,531 (25.67) | 142,275 (24.69) | 178,256 (26.51) |

| 8-21 days | 63,766 (5.11) | 26,074 (4.52) | 37,692 (5.6) |

| >21 days | 230,650 (18.47) | 103,874 (18.03) | 126,776 (18.85) |

| No prior MI | 587,291 (47.03) | 282,501 (49.03) | 304,790 (45.32) |

| Prior PCI | |||

| Timing missing | 886 (0.07) | 316 (0.05) | 570 (0.08) |

| PCI ≤6 h | 12,572 (1) | 6,036 (1.04) | 6,536 (0.97) |

| PCI >6 h | 362,521 (28.9) | 166,041 (28.7) | 196,480 (29.07) |

| No prior PCI | 878,339 (70.03) | 406,068 (70.2) | 472,271 (69.88) |

| Mitral regurgitation | |||

| Severe | 5,312 (0.46) | 1,834 (0.35) | 3,478 (0.55) |

| Moderate | 75,447 (6.54) | 29,095 (5.58) | 46,352 (7.33) |

| Mild | 278,523 (24.15) | 113,827 (21.84) | 164,696 (26.05) |

| Trivial | 295,749 (25.64) | 114,860 (22.04) | 180,889 (28.61) |

| None | 498,361 (43.21) | 261,597 (50.19) | 236,764 (37.45) |

| Aortic regurgitation | |||

| Severe | 603 (0.05) | 272 (0.05) | 331 (0.05) |

| Moderate | 17,880 (1.58) | 7,249 (1.42) | 10,631 (1.72) |

| Mild | 91,606 (8.1) | 37,009 (7.25) | 54,597 (8.81) |

| Trivial | 115,170 (10.19) | 42,226 (8.27) | 72,944 (11.77) |

| None | 905,147 (80.07) | 423,954 (83.01) | 481,193 (77.65) |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | |||

| Severe | 2,664 (0.24) | 1,044 (0.2) | 1,620 (0.26) |

| Moderate | 35,078 (3.1) | 14,046 (2.75) | 21,032 (3.39) |

| Mild | 221,415 (19.58) | 93,182 (18.25) | 128,233 (20.67) |

| Trivial | 343,400 (30.36) | 133,983 (26.24) | 209,417 (33.75) |

| None | 528,512 (46.73) | 268,401 (52.56) | 260,111 (41.93) |

| Pre-operative laboratory values | |||

| Hematocrit, % | 39.8 (36.0-43.0) | 39.8 (36.0-43.0) | 39.7 (35.9-43.0) |

| White blood cell count, cells × 109 l | 7.7 (6.3-9.4) | 7.7 (6.3-9.3) | 7.7 (6.3-9.4) |

| Platelet count, cells × 109 l | 208 (172-251) | 208 (172-250) | 208 (172-251) |

| Hemoglobin A1C, % | 6.1 (5.6-7.3) | 6.1 (5.6-7.3) | 6.1 (5.6-7.4) |

| Median annual CABG volume per center, cases/yr | 200.8 (122.2-308.1) | 204.1 (126.5-322.4) | 193.9 (117.9-293.6) |

| Region | |||

| Other | 14,343 (1.14) | 7,667 (1.32) | 6,676 (0.99) |

| Midwest | 290,974 (23.17) | 146,515 (25.3) | 144,459 (21.34) |

| West | 199,647 (15.9) | 67,121 (11.59) | 132,526 (19.58) |

| South | 549,750 (43.77) | 278,823 (48.15) | 270,927 (40.03) |

| Northeast | 201,146 (16.02) | 78,931 (13.63) | 122,215 (18.06) |

| 11: West South Central | 157,219 (12.52) | 90,229 (15.58) | 66,990 (9.9) |

| 10: South Atlantic | 274,055 (21.82) | 116,278 (20.08) | 157,777 (23.31) |

| 9: West North Central | 85,076 (6.77) | 49,905 (8.62) | 35,171 (5.2) |

| 8: Pacific | 137,083 (10.92) | 48,570 (8.39) | 88,513 (13.08) |

| 7: Not North America | 5,645 (0.45) | 4,116 (0.71) | 1,529 (0.23) |

| 6: New England | 50,868 (4.05) | 13,898 (2.4) | 36,970 (5.46) |

| 5: Mountain | 62,564 (4.98) | 18,551 (3.2) | 44,013 (6.5) |

| 4: Middle Atlantic | 150,278 (11.97) | 65,033 (11.23) | 85,245 (12.6) |

| 3: East North Central | 205,898 (16.39) | 96,610 (16.68) | 109,288 (16.15) |

| 2: East South Central | 118,476 (9.43) | 72,316 (12.49) | 46,160 (6.82) |

| 1: Canada | 8,698 (0.69) | 3,551 (0.61) | 5,147 (0.76) |

| Cardiac presentation at time of surgery | |||

| Other | 38,202 (4.61) | 14,020 (4.05) | 24,182 (5.01) |

| STEMI | 29,253 (3.53) | 12,076 (3.49) | 17,177 (3.56) |

| Non-STEMI | 36,297 (4.38) | 14,171 (4.09) | 22,126 (4.58) |

| Unstable angina | 180,944 (21.83) | 70,661 (20.42) | 110,283 (22.84) |

| Stable angina | 303,085 (36.56) | 125,577 (36.28) | 177,508 (36.76) |

| Symptoms unlikely to be ischemia | 135,971 (16.4) | 60,161 (17.38) | 75,810 (15.7) |

| No symptoms | 105,187 (12.69) | 49,422 (14.28) | 55,765 (11.55) |

| Status | |||

| Emergent salvage | 2,212 (0.18) | 1,030 (0.18) | 1,182 (0.17) |

| Emergent | 52,867 (4.21) | 23,921 (4.13) | 28,946 (4.28) |

| Urgent | 724,874 (57.74) | 325,090 (56.16) | 399,784 (59.09) |

| Elective | 475,535 (37.88) | 228,845 (39.53) | 246,690 (36.46) |

| Full | 1,064,410 (84.77) | 482,580 (83.35) | 581,830 (85.98) |

| Combination | 13,616 (1.08) | 6,101 (1.05) | 7,515 (1.11) |

| None | 177,674 (14.15) | 90,304 (15.6) | 87,370 (12.91) |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%).

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ADP = adenosine diphosphate; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; MI = myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

OUTCOMES ASSOCIATED WITH TEE AT TIME OF CABG.

Unadjusted operative complications and outcomes are shown in Table 2. TEE use was associated with lower median total ventilation time (5.8 h vs. 6.1 h; p < 0.0001) and slightly longer duration of ICU stay (2 days vs. 1.9 days; p < 0.0001). Patients with intraoperative TEE were more likely to have a post-operative echocardiogram performed (15.2% vs. 11.6%), and median post-operative EF was lower for those with TEE than without (50% vs. 53%; p < 0.0001). Unadjusted post-operative complications and mortality rates were higher in the TEE group, including higher rates of renal failure, cardiac arrest, operative mortality, hospital readmission, and major morbidity (Table 2). CABG patients who received intraoperative TEE had a 12.5% rate of major morbidity or mortality compared with 11.6% for those who did not receive intraoperative TEE (p < 0.0001).

TABLE 2.

Outcomes for CABG Patients Who Received Intraoperative TEE Versus Non-TEE Patients

| Overall (N = 1,255,860) |

No TEE (n = 579,057) |

TEE (n = 676,803) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-operative creatinine level, mg/dl | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 1.1 (0.9-1.5) |

| Total ventilation time, h | 5.93 (3.97-11.17) | 6.05 (4.05-11.15) | 5.83 (3.92-11.20) |

| Duration of ICU stay, days | 1.96 (1.06-3.15) | 1.92 (1.04-3.04) | 2.00 (1.08-3.28) |

| Post-operative echo performed | 168,196 (13.52) | 66,442 (11.57) | 101,754 (15.19) |

| Post-operative ejection fraction | 52.0 (38.0-60.0) | 53.0 (40.0-60.0) | 50.0 (38.0-60.0) |

| Readmission to the ICU | 35,116 (2.8) | 16,222 (2.81) | 18,894 (2.8) |

| Deep sternal wound infection | 4,109 (0.33) | 1,795 (0.31) | 2,314 (0.34) |

| Reoperation for bleeding/tamponade | 22,050 (1.76) | 10,085 (1.74) | 11,965 (1.77) |

| Reoperation for bleeding, valve, graft, other cardiac, MI, aortic | 29,591 (2.36) | 13,315 (2.31) | 16,276 (2.41) |

| Sepsis | 11,149 (0.89) | 4,742 (0.82) | 6,407 (0.95) |

| Stroke/TIA | 19,001 (1.52) | 8,421 (1.46) | 10,580 (1.57) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 9,565 (0.76) | 4,055 (0.7) | 5,510 (0.82) |

| Prolonged ventilation | 104,348 (8.32) | 45,667 (7.9) | 58,681 (8.68) |

| Pleural effusion requiring drainage | 44,336 (3.66) | 19,252 (3.49) | 25,084 (3.81) |

| Renal failure | 26,415 (2.18) | 11,068 (1.97) | 15,347 (2.35) |

| Cardiac arrest | 22,668 (1.81) | 9,782 (1.69) | 12,886 (1.91) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 303,494 (24.2) | 135,721 (23.47) | 167,773 (24.82) |

| Operative mortality | 27,117 (2.29) | 12,117 (2.24) | 15,000 (2.33) |

| Major morbidity | 142,787 (11.42) | 63,094 (10.94) | 79,693 (11.83) |

| Major morbidity or mortality, operative mortality | 151,566 (12.08) | 67,327 (11.63) | 84,239 (12.46) |

| Readmission within 30 days | 123,448 (10.35) | 56,492 (10.23) | 66,956 (10.45) |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%).

ICU = intensive care unit; TIA = transient ischemic attack; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

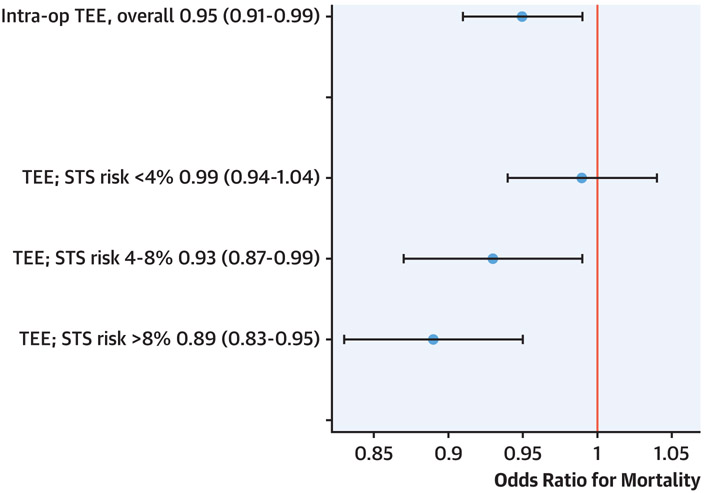

Prior to matching and with multivariable adjustment, patients undergoing intraoperative TEE had greater odds of longer ICU stay (OR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.25; p = 0.0033) and renal failure (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.15; p = 0.0004), and a lower risk of operative mortality (OR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.91 to 0.99; p = 0.020. The propensity matching resulted in 560,639 CABG patients undergoing intraoperative TEE matched with 560,639 CABG patients who did not. The clinical characteristics and outcomes of the matched groups are displayed in Supplemental Table 3. After propensity matching and multivariable adjustment, results were similar. Patients undergoing intraoperative TEE had greater odds of longer ICU stay (OR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.15; p25 = 0.0034) and renal failure (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.15; p = 0.0006), and a lower risk of operative mortality (OR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.91 to 0.99; p = 0.025) (Figure 1). In a sensitivity analysis excluding pre-operative valve disease from the propensity score and adjustment, the point estimate was similar but no longer statistically significant (OR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.96 to 1.01; p = 0.089). There was heterogeneity in the association of TEE use with outcome across STS risk groups (Table 3, Figure 1). After adjustment, TEE was associated with lower odds of death in the high-risk group (OR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.83 to 0.95) and intermediate-risk group (OR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.87 to 0.99), but not in the low-risk group (OR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.94 to 1.04; p for interaction = 0.0147) (Figure 1). In a sensitivity analysis excluding pre-operative valve disease from the propensity score and adjustment, these results were overall similar: after adjustment, TEE was associated with lower odds of death in the high-risk group (OR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.84 to 0.96) with progressively less impact in the intermediate-risk (OR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.89 to 1.01) and low-risk groups (OR: 1.0; 95% CI: 0.94 to 1.04; p for interaction = 0.022).

FIGURE 1. Association of Intraoperative TEE Usage With Mortality in 1.3 Million Isolated CABG Procedures.

Displayed are odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) with operative mortality overall and stratified by Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk. Models are fully adjusted for clinical characteristics and use propensity-matched data. CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting.

TABLE 3.

Odds Ratios for the Association of Intraoperative TEE With Outcome Using the Propensity-Matched Model Adjustment Was Performed Using Covariates in Supplemental Table 1

| Outcome | Odds Ratio (TEE Versus No TEE) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Operative mortality | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | 0.0251 |

| Hospital readmission | 0.99 (0.96-1.01) | 0.2907 |

| Prolonged mechanical ventilation | 1.00 (0.95-1.04) | 0.8717 |

| ICU stay longer than 2 days | 1.14 (1.05-1.25) | 0.0034 |

| Re-operation | 1.00 (0.95-1.04) | 0.8639 |

| Renal failure | 1.09 (1.04-1.15) | 0.0006 |

| Outcome | Odds Ratio (TEE Versus No TEE) Stratified by STS Risk |

p Value for Interaction |

| Operative mortality | ||

| Low risk | 0.99 (0.94-1.04) | 0.0147 |

| Medium risk | 0.93 (0.87-0.99) | |

| High risk | 0.89 (0.83-0.95) | |

| Hospital readmission | ||

| Low risk | 0.98 (0.96-1.01) | 0.4928 |

| Medium risk | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) | |

| High risk | 1.00 (0.94-1.06) | |

| Prolonged mechanical ventilation | ||

| Low risk | 0.99 (0.94-1.04) | 0.2941 |

| Medium risk | 1.00 (0.94-1.06) | |

| High risk | 1.04 (0.97-1.11) | |

| ICU stay longer than 2 days | ||

| Low risk | 1.15 (1.05-1.26) | 0.0488 |

| Medium risk | 1.10 (1.00-1.22) | |

| High risk | 1.19 (1.06-1.33) | |

| Re-operation | ||

| Low risk | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.0165 |

| Medium risk | 1.10 (1.01-1.20) | |

| High risk | 1.04 (0.94-1.14) | |

| Renal failure | ||

| Low risk | 1.10 (1.04-1.17) | 0.6375 |

| Medium risk | 1.06 (0.99-1.15) | |

| High risk | 1.08 (0.99-1.18) |

The location and causes of mortality are shown in Supplemental Table 4. For those with available data, there was a greater than 2 times higher risk of death in the operating room during initial surgery for patients who did not receive TEE compared with those who did. The causes of death described by organ system were overall similar between groups.

In the cohort of 831,528 patients assessing TEE in relation to unplanned valve operation, 485,312 (58.4%) underwent TEE. Overall, 2,691 (0.32%) patients planned for isolated CABG required unplanned valve procedure, including 251 tricuspid valves, 3 pulmonary valves, 917 aortic valves, and 1,611 mitral valves. Of CABG patients undergoing TEE, 0.49% had unplanned valve procedure compared with 0.09% of those not undergoing TEE (absolute risk difference 0.4%). Propensity score matching resulted in 346,508 CABG with possible unplanned valve operation who underwent TEE matched with 346,508 patients who did not undergo TEE. After multivariable adjustment and matching, TEE was associated with nearly 5-fold higher odds of an unplanned valve procedure at time of planned isolated CABG (OR: 4.98; 95% CI: 3.98 to 6.22; p < 0.0001). In a sensitivity analysis excluding pre-operative valve disease from the propensity score and adjustment, results were similar (OR: 5.09; 95% CI: 4.10 to 6.34; p < 0.0001). Odds of an unplanned valve procedure did not differ significantly across STS risk groups (p for interaction = 0.56).

DISCUSSION

In this nationwide study of 1.3 million isolated CABG procedures across 1,218 centers, we report several major findings. First, intraoperative TEE usage is increasing; yet, it remains variable across centers and regions. Second, CABG patients who receive intraoperative TEE have a higher risk profile; yet, TEE is associated with lower operative mortality, particularly among those CABG patients with greatest predicted operative risk (Central Illustration). Finally, intraoperative TEE is associated with increased odds of an unplanned valve procedure at time of CABG, suggesting that TEE can identify patients with occult valvular pathology and affect the operative plan (Central Illustration). Taken together, our results support the use of intraoperative TEE to improve outcomes in patients undergoing isolated CABG, particularly among the highest-risk patients. Conversely, outcomes may not be affected by TEE in CABG patients who are at the lowest operative risk. If TEE is initially deferred, however, it should be used if the patient risk profile shifts to a higher level at any point in the operation, representing a pragmatic, adaptive, and risk-guided approach to perioperative imaging.

NATIONAL UTILIZATION OF TEE AT THE TIME OF ISOLATED CABG.

Intraoperative TEE to support CABG is a guideline-recommended means to assess intraoperative cardiac structure and function, given a Class IIa recommendation in the last CABG guidelines (4). We report that the proportion of isolated CABG patients undergoing TEE is variable across centers and overall increasing over time, with 62% of CABG patients receiving TEE in 2019. Other authors have also reported an increasing usage of echocardiography in general during hospitalization for cardiovascular disorders (24). Our findings are representative of the U.S. practice as a whole, given that over 90% of hospitals performing cardiac surgery in the United States are represented in the STS ACSD (25). Factors associated with use of TEE included those connoting greater patient risk: urgent and emergent status; cerebrovascular, pulmonary, and hepatic disease; lower LVEF; and known valve disease. We also describe geographic variation in TEE usage, consistent with a report corroborating geographic variation in TEE use for valve surgery (19) and CABG alike (21). Hospitals in the Midwest and South were less likely to use TEE, which suggests an opportunity to consider distribution of the perioperative imaging workforce and ensuring equal availability. The increased usage of TEE at training programs could be a function of patient risk profile, referral-based population, focus on TEE as a component of resident training, and other factors. Supporting this premise is the fact that anesthesiologists with TEE training favored use of TEE for hemodynamic monitoring rather than a pulmonary artery catheter (26).

OUTCOMES ASSOCIATED WITH USE OF TEE DURING CABG.

Intraoperative TEE was associated with reduced mortality after adjustment for the higher patient risk profile. Although consideration of TEE for isolated CABG patients has been recommended by guidelines with a moderately strong recommendation (1-4,27), evidence that intraoperative TEE improves outcomes has been lacking. MacKay et al. (20) report that TEE was associated with reduced mortality when used for heart valve operations, and Savage et al. (18) reported no difference in mortality in an older, small study. A recent study of Medicare beneficiaries undergoing CABG also reported reduced mortality with TEE, using an instrumental variable approach (28). Our findings are consistent, therefore, in providing generalizable evidence that TEE is associated with reduced mortality in isolated CABG and support current and updated guideline recommendations. This is particularly true among patients who are at the highest perioperative risk. It is unlikely that a definitive randomized trial of TEE could be effectively conducted; therefore, inference from observational studies such as ours is necessary to support guideline recommendations. Our data also support that TEE may not improve outcomes in the lowest-risk patients, and TEE could possibly be deferred safely in this subgroup. Although the risk reduction is small in terms of absolute benefit, given the number of CABG procedures performed, this risk reduction is important at a population level. As such, to maximize benefit of TEE at the population level, one would ensure that the highest-risk patients are operated on at centers that offer TEE.

MECHANISMS BY WHICH TEE COULD IMPROVE OUTCOMES.

There are several potential mechanisms by which TEE could improve outcomes. First, TEE could reveal unexpected structural changes leading to changes in operative conduct as reported in other studies (13,14,16,17,29). Our results support this premise, given that TEE use was associated with greater odds of an unplanned valve operation at time of planned isolated CABG. TEE after weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass can also identify new regional wall motion abnormalities, suggesting ischemia and directing therapy to ameliorate ischemia and improve outcome (12,30). Similarly, post-bypass right heart failure, pericardial effusion, or aortic injury can be identified. Finally, a high-risk TEE could lead to changes in the course of immediate post-operative therapy in the ICU, which may explain our observation that TEE was associated with a longer ICU length of stay. Examples of directed ICU therapy affected by echocardiography would include inotrope titration and management of right heart failure.

Our finding that TEE use was associated with increased risk of renal failure is consistent with at least 1 other large, national study (21). MacKay et al. (21,22) reported that intraoperative TEE use in CABG was associated with increased risk of acute renal failure, which attenuated after an instrumental variable analysis, suggesting that the observed increased risk was due to unmeasured confounding. An alternate explanation could be that TEE use is associated with different patterns of vasoactive medication or inotrope use or fluid management strategies, which in turn predispose to kidney injury. This ambiguity points to a need to study standardized goal-directed vasoactive medication and fluid management strategies that incorporate TEE-based hemodynamics (31).

STUDY LIMITATIONS.

Limitations of our study include that the STS ACSD does not include information as to TEE complications such as esophageal perforation. Moreover, the specific personnel performing the TEE—whether cardiologists or anesthesiologists—and their training and certification in the modality are not captured in the database. TEE is overall safe, with complications reported between 1 in 100 and 1 in 1,000 patients (10,11); yet, complications can be severe when they occur. The rate of severe complications such as esophageal perforation is on the order of 1 in 10,000 cases when performed by experienced operators (32), and the more common complications include pharyngeal trauma and odynophagia, which generally resolve with expectant management (33,34). If TEE use is to be expanded, rigorous attention to proper technique, training, and monitoring for complications is mandatory. The observational nature of our study supports a lesser certainty of inference than a randomized trial; however, a randomized trial addressing this question is unlikely to be performed, supporting the premise that the evidence base for TEE should arise from well-conducted observational studies. As regards the association of TEE with unplanned valve procedure, we acknowledge that pre-operative surgeon intent is difficult to fully ascertain from a binary classification; for example, some institutions may routinely use TEE to make intraoperative decisions as to whether to perform restrictive mitral annuloplasty. Moreover, the temporality of use of TEE and decision to perform valve surgery are such that the causal pathway could be confounded. Even so, such an example serves the inference that TEE is associated with intraoperative, impactful decisions. Finally, the ascertainment of mortality in the STS database may be incomplete for those patients who die within 30 days of surgery but after hospital discharge (35); however, misclassifying out-of-hospital mortality did not substantially impact overall program rank (36).

CONCLUSIONS

In 1.3 million isolated CABG procedures across 1,218 U.S. centers, intraoperative TEE usage is heterogenous. TEE is associated with a greater frequency of unplanned changes to the proposed surgery and lower operative mortality. Our findings support the use of TEE for isolated CABG to improve outcomes in the highest-risk patients, whereas TEE may possibly be deferred safely in patients at low risk.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE AND PROCEDURAL SKILLS:

Intra-operative transesophageal echocardiography findings during CABG surgery frequently result in procedural modification and are associated with lower operative mortality, particularly among high-risk patients.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK:

These observations should be considered by developers of clinical practice guidelines in formulating recommendations for imaging guidance in patients undergoing CABG surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The data for this research were provided by The Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ National Database Access and Publications Research Program.

FUNDING SUPPORT AND AUTHOR DISCLOSURES

Dr. Metkus has received salary support from the National Institutes of Health-funded Institutional Career Development Core at Johns Hopkins (project number 5KL2TR003099-02).

Dr. Grant has received salary support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (contract number HHSP233201500020I). All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- ACSD

Adult Cardiac Surgery Database

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- ICU

intensive care unit

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

- TEE

transesophageal echocardiography

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

APPENDIX For supplemental tables and the supplemental figures, please see the online version of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography. Anesthesiology 1996;84:986–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Society of Anesthesiologists, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography. Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography. Anesthesiology 2010;112:1084–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn RT, Abraham T, Adams MS, et al. Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26:921–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2584–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicoara A, Skubas N, Ad N, et al. Guidelines for the use of transesophageal echocardiography to assist with surgical decision-making in the operating room: a surgery-based approach: from the American Society of Echocardiography in Collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2020;33:692–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couture P, Denault AY, McKenty S, et al. Impact of routine use of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography during cardiac surgery. Can J Anaesth 2000;47:20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mavi M, Celkan MA, Ilcol B, Turk T, Yavuz S, Ozdemir A. Hemodynamic and transesophageal echocardiographic analysis of global and regional myocardial functions, before and immediately after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Card Surg 2005;20:147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephens RS, Whitman GJ. Postoperative critical care of the adult cardiac surgical patient: part II: procedure-specific considerations, management of complications, and quality improvement. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1995–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephens RS, Whitman GJ. Postoperative critical care of the adult cardiac surgical patient. Part I: routine postoperative care. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1477–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piercy M, McNicol L, Dinh DT, Story DA, Smith JA. Major complications related to the use of transesophageal echocardiography in cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009;23:62–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purza R, Ghosh S, Walker C, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography complications in adult cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kihara C, Murata K, Wada Y, et al. Impact of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in cardiac and thoracic aortic surgery: experience in 1011 cases. J Cardiol 2009;54:282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minhaj M, Patel K, Muzic D, et al. The effect of routine intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography on surgical management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2007;21:800–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qaddoura FE, Abel MD, Mecklenburg KL, et al. Role of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients having coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:1586–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sousa RC, Garcia-Fernandez MA, Moreno M, et al. [The contribution and usefulness of routine intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in cardiac surgery. An analysis of 130 consecutive cases]. Rev Port Cardiol 1995;14:15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eltzschig HK, Rosenberger P, Loffler M, Fox JA, Aranki SF, Shernan SK. Impact of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography on surgical decisions in 12,566 patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:845–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein AA, Snell A, Nashef SA, Hall RM, Kneeshaw JD, Arrowsmith JE. The impact of intraoperative transoesophageal echocardiography on cardiac surgical practice. Anaesthesia 2009;64:947–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savage RM, Lytle BW, Aronson S, et al. Intraoperative echocardiography is indicated in high-risk coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:368–73; discussion 373–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacKay EJ, Groeneveld PW, Fleisher LA, et al. Practice pattern variation in the use of transesophageal echocardiography for open valve cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2019;33:118–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKay EJ, Neuman MD, Fleisher LA, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography, mortality, and length of hospitalization after cardiac valve surgery. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2020;33:756–62.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKay EJ, Werner RM, Groeneveld PW, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography, acute kidney injury, and length of hospitalization among adults undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2020;34:687–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato K, Bainbridge D. Transesophageal echocardiography and outcomes in coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: dealing with confounders in observational studies. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2020;34:696–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Overman DM, Jacobs JP, Prager RL, et al. Report from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database Workforce: clarifying the definition of operative mortality. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2013;4:10–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papolos A, Narula J, Bavishi C, Chaudhry FA, Sengupta PPUS. hospital use of echocardiography: insights from the nationwide inpatient sample. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:502–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandez FG, Shahian DM, Kormos R, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database 2019 annual report. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;108:1625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacka MJ, Cohen MM, To T, Devitt JH, Byrick R. The use of and preferences for the transesophageal echocardiogram and pulmonary artery catheter among cardiovascular anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg 2002;94:1065–71. Table of Contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn RT, Abraham T, Adams MS, et al. Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg 2014;118:21–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacKay EJ, Zhang B, Heng S, et al. Association between transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and clinical outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) Surgery. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2021. Jan 26 [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva F, Arruda R, Nobre A, et al. Impact of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in cardiac surgery: retrospective analysis of a series of 850 examinations. Rev Port Cardiol 2010;29:1363–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swaminathan M, Morris RW, De Meyts DD, et al. Deterioration of regional wall motion immediately after coronary artery bypass graft surgery is associated with long-term major adverse cardiac events. Anesthesiology 2007;107:739–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ripolles-Melchor J, Casans-Frances R, Espinosa A, et al. Goal directed hemodynamic therapy based in esophageal Doppler flow parameters: a systematic review, meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2016;63:384–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Min JK, Spencer KT, Furlong KT, et al. Clinical features of complications from transesophageal echocardiography: a single-center case series of 10,000 consecutive examinations. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:925–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kallmeyer IJ, Collard CD, Fox JA, Body SC, Shernan SK. The safety of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography: a case series of 7200 cardiac surgical patients. Anesth Analg 2001;92:1126–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilberath JN, Oakes DA, Shernan SK, Bulwer BE, D’Ambra MN, Eltzschig HK. Safety of transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:1115–27. quiz 1220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobs JP, O’Brien SM, Shahian DM, et al. Successful linking of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database to Social Security data to examine the accuracy of Society of Thoracic Surgeons mortality data. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;145:976–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hannan EL, Samadashvili Z, Cozzens K, et al. Out-of-hospital 30-day deaths after cardiac surgery are often underreported. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;110:183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.