Abstract

Heterochromatin represents a cytologically visible state of heritable gene repression. In the yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the swi6 gene encodes a heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1)-like chromodomain protein that localizes to heterochromatin domains, including the centromeres, telomeres, and the donor mating-type loci, and is involved in silencing at these loci. We identify here the functional domains of swi6p and demonstrate that the chromodomain from a mammalian HP1-like protein, M31, can functionally replace that of swi6p, showing that chromodomain function is conserved from yeasts to humans. Site-directed mutagenesis, based on a modeled three-dimensional structure of the swi6p chromodomain, shows that the hydrophobic amino acids which lie in the core of the structure are critical for biological function. Gel filtration, gel overlay experiments, and mass spectroscopy show that HP1 proteins can self-associate, and we suggest that it is as oligomers that HP1 proteins are incorporated into heterochromatin complexes that silence gene activity.

The highly conserved heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) class of chromobox genes (HP1) encode structural adapters whose probable role is to assemble a variety of macromolecular complexes in chromatin (30). The possible functions of these complexes are wide-ranging and include roles in transcriptional repression (12, 36, 54, 55), transgene silencing (17, 26), chromosome segregation (14, 31), recruitment of silent genes to heterochromatin (7, 54), localization of heterochromatin to the nuclear periphery (67), and sex chromosome inactivation during mammalian spermatogenesis (44).

The swi6 gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is a nonessential gene that is required for the recombination-suppression and silencing which encompasses the mat2-K-mat3 region (33). Cloning of the gene showed that swi6 is a member of the HP1 class of chromobox genes (38), suggesting that the recombination-suppression and silencing are due to the packaging of the mat2-K-mat3 region into a heterochromatin-like complex that renders the region inaccessible to the transcriptional and recombination machinery (38, 63). Other trans-acting factors that are required for repression at the silent loci include rik1, clr1, clr2, clr3, clr4, and clr6 (34, 64). rik1, clr1, and clr4 are thought to encode structural components of the heterochromatin-like complex, while clr3 and clr6 share considerable homology with histone deacetylases (20). Along with the silent mating-type loci, swi6p is also involved in silencing at the fission yeast centromeres and telomeres (14, 47) and plays a role in chromosome segregation at anaphase (14).

HP1 proteins are characterized by the possession of both a classical chromodomain (CD) and a chromo shadow domain (CSD) (2) linked by a variable intervening region (IVR) or “hinge” (16). In addition, a stretch of acidic amino acids immediately precedes the CD of HP1 proteins (see Fig. 1A). The solution structure of the CD from the murine HP1-like heterochromatin-associated protein, M31 (also known as mHP1β and MOD1) (58, 65), has been elucidated by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and shown to consist of an N-terminal three-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet which packs against a C-terminal α-helix (4). The most highly conserved residues are contained within the hydrophobic core of the CD structure, and most of these conserved residues are to be found at the bottom of a hydrophobic groove on the surface of the β-pleated sheets under the α-helix.

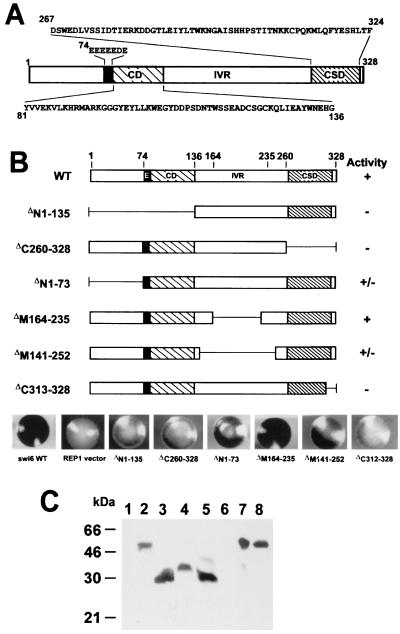

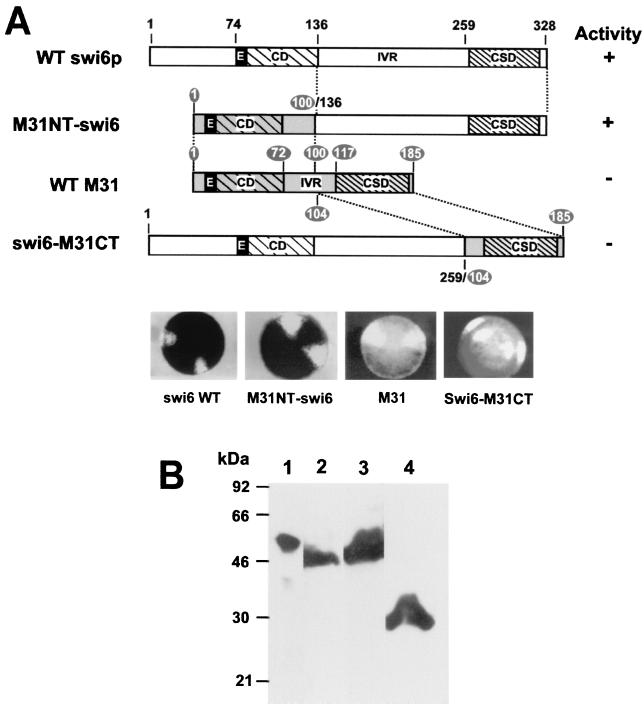

FIG. 1.

Activity of swi6p N-terminal, C-terminal, and internal deletion mutants. (A) Organization of swi6p. The black box represents the glutamic acid region. (B) swi6p deletion mutants. The activities of each mutant in sporulation assays and minichromosome loss experiments (see Table 1) are summarized on the right. Examples of iodine-stained colonies for each transformant are shown below. (C) Western blot showing expression of wt and deletion mutant swi6p. Except for lanes 1 and 2, all lanes correspond to swi6 deletion strain AL91L transformed with the described REP81-swi6p deletion mutants. Lanes: 1, strain AL91L; 2 and 7, strain SP557 (wt); 3, ΔN1–135; 4, ΔN1–73; 5, ΔM164–235; 6, ΔC313–328; 8, wt swi6p. The blot was probed with monoclonal antibody MAC391.

The precise role of CD proteins in the assembly of heterochromatin-like complexes is unknown, although a series of experiments involving deletions and a few natural and experimentally induced point mutations within the archetypal Drosophila chromodomain proteins, HP1 and Polycomb (Pc), have shown that the CD is crucial for function (18, 41, 50, 51). Moreover, chromodomain-swap experiments have shown that CD-containing proteins are likely to be directed to specific sites within the genome through a CD-CD interaction (50). Little is known about the stoichiometry of CD proteins in heterochromatin complexes, although a model of heterochromatin assembly, the mass-action model (62), based on the sensitivity of variegating phenotypes to changes in the dosage of structural components of heterochromatin, such as HP1, suggests that oligomers of such structural components may be incorporated into heterochromatin(-like) complexes.

In this study we identify the functional domains of swi6p and demonstrate that the M31 CD can functionally replace the CD of swi6p, showing that classical CD function is conserved from yeasts to humans. Given this conservation, we have undertaken a mutational analysis of the conserved amino acids in the swi6p CD. Using three functional assays, that measure silencing at the mating-type loci and chromosome segregation, we show that the hydrophobic amino acids which lie in the core of the CD are the most important for proper function. We also show that HP1 proteins can self-associate and can form oligomers in vitro. We suggest that it is as oligomers that HP1 proteins are incorporated into heterochromatin complexes that silence gene activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of strains used.

Three crosses were required to produce the strain used for the chromosome loss rate assay. Random spore analysis was used throughout (42). The wild-type (wt) S. pombe strain SP11 (h− ade6-704 ura4D-18 leu1-32) (11) was crossed with swi6 null strain AL91 (h90 swi6::ura4+ ura4-D18 ade6-M216) (38) to obtain AL91L (h90 Swi6::ura4+ ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-704), which produced a strain that contained both the swi6 null mutation and the ade6-704 mutation. Second, strain CN2 (h+ leu1-32 ade6-704) carrying the minichromosome Ch10 (sup3-5) (60) was crossed with SP11 to obtain strain SPCN3 (h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-704/Ch10::sup3-5). SPCN3 contains both the ade6-704 mutation and its suppressor, sup3-5, which is carried on the minichromosome, Ch10. Finally, the swi6 null mutation was introduced into SPCN3 by crossing SPCN3 with AL91L to obtain strain CN91L (h90 leu1-32 swi6::ura4-D18 ade6-704/Ch10::sup3-5). CN91L was used to determine the minichromosome loss rate (MCLR) associated with each of the swi6 mutations used in this study (see below). Deletion of swi6 in CN91L was confirmed by PCR and Southern blotting (42).

S. pombe media.

Media were essentially as described earlier (42). For chromosome loss tests, Edinburgh minimal medium (EMM) plates were supplemented with 0.15 the normal amount of adenine (12 mg/liter).

Site-directed mutagenesis and construction of yeast expression plasmids.

swi6 wt cDNA was cloned to pGEX (Promega) vector by reverse transcription-PCR and confirmed by sequencing. The fission yeast expression vector pREP81 (40) was used for expression of the wt and mutant swi6p proteins in AL91L and CN91L strains. This vector utilizes the thiamine-repressible yeast nmt promoter (39) with a mutated TATA box and gives one level of expression in transformed null cells equivalent to the swi6p level in the wt strain SP557. For nuclear localization experiments, the higher-level expression vector pREP1 was also employed. All swi6 mutants were generated by PCR and PCR extension (27). pGEX-swi6 wild type was used as a template. Taq polymerase was purchased from Boehringer.

(i) Primers used to generate point mutations in swi6p.

For all the primers listed below, the position in the swi6 or M31 cDNA sequence, in relation to the A of the initiation AUG codon, of the 3′ nucleotide is indicated. For all point mutations the external primers were the 5′-ApaI primer GAAGGGCCCAATGAAGAAAGGAGGTGTTCG20 and the 3′-BamHI primer CACGGATCCATTATTCATTTTCACGGA970. The inner primers for each point mutation were, for, E74-D79E80 to A74-80, the 5′-3′ primer GGAGGAGCAGCAGCAGCAGCG-GCTGCATATGTTGTA249 and the 3′-5′ primer TGCTGCTGCTGCTCCTCCTTCTTCTTC207; for E74-D79E80 to R74-80, the 5′-3′ primer (GGAGACGGCGAAGATATGTTGTAGAAAAG255 and the 3′-5′ primer TTCGCCGTCTCCTTCTTCTTCCTCCTTCT206; for the NTW(113–115) deletion, the 5′-3′ primer AGTGATAGTTCAGAAGCCGATT361 and the 3′-5′ primer TGAACTATCACTGGGATCGTC322; for W115 to G, the 5′-3′ primer ATAATACAGGGAGTTCAGAAGCCG358 and the 3′-5′ primer CCCTGTATTGTCACTGGGATCGTC322; for Y100Y107 to CC, the 5′-3′ primer TTGAAATGGGAAGGTTRTGAC324 and the 3′-5′ primer TCCCCATTTCAAAAGGYATCC295; for W293 to G, the 5′-3′ primer ACTKGGRAGAACGGTGCAATAT895 and the 3′-5′ primer GTTCTYCCMAGTCAGGTAAATT865; for K103W104 to VV, the 5′-3′ primer TTGGTAGTGGAAGGTTATGACGAT327 and the 3′-5′ primer TTCCACTACCAAAAG-GTATTCATAGC290; for E84 to F, the 5′-3′ primer TTTAAGGTTTTAAAACACCGT270 and the 3′-5′ primer TAAAACCTTAAATACAACATATTC300; for L101L102 to NN, the 5′-3′ primer TACAACAACAAATGGGAAGGTTATGAC324 and the 3′-5′ primer TTTGTTGTTGTATTCATAGCCTCCAC284; for M91A92 to VV, the 5′-3′ primer GTCTAGTAAGAAAAGGTGGAGGC291 and the 3′-5′ primer CCTTTTCTTACTAGACGGTGTTTT260; for K103 to Q, the 5′-3′ primer TTGCAATGGGAAGGTTATGACGAT327 and the 3′-5′ primer TTCCCATTGCAAAAGGTAT-TCATAGC290; and for M91A92 to QG, the 5′-3′ primer CCGTCAGGGGAGAAAAGGTGGAGGC291 and the 3′-5′ primer TTTTCTGGGCTGACGGTGTTTTA259.

(ii) Primers used for generation of deletion mutants.

The primers for the generation of deletion mutants were: for the ΔC260–258 deletion, the 3′-5′ primer CGGGATCCTAGCTAGCCGTCAGCTCTCTGTTGTC760; for the ΔM164–235 deletion, the 5′-3′ primer TCTCGTCCTAGCAATGTTACTCC722 and the 3′-5′ primer GCTAGGACGAGA-CTTTGGTGAAG473; for the ΔN1–73 deletion, the 5′-3′ primer GACGGGCCCATGG-AAGAAGAAGAAGAGGAT136; for the ΔN1–135 deletion, the 5′-3′ primer GCGGGCCCATATGATAGCTAGCGGAGGAAGACCAGAACC422; for the ΔC 313–328 deletion, the 3′-5′ BglII primer GGAGATCTTACTGAGGACATTTTTTATTG918; and for the ΔM141–252 deletion, the 5′-3′ primer GAAGACCAGAACCGGACAACAGAGAG771 and the 3′-5′ primer GGTTCTGGTCTTCCTC407.

(iii) swi6p-M31 domain-swap primers.

The Swi6p-M31 domain-swap primers were the M31 cDNA 5′-3′ XhoI primer GCACTCGAGATGGGGAAAAAGCAAAAC18, the M31 3′-5′ BamHI primer GTGGATCCGAAGGCTGTGGGTTGTGG, the M31 Chromobox I 3′-5′ NheI primer ATCAGAGCTAGCCCATTTCATCAGGAA400, and the M31 Chromobox II 5′-3′ NheI primer AAGGCTAGCAAAGAAGAGTCAGAAAAG238.

M31NT-swi6 was constructed as follows. cDNA encoding residues 1 to 100 of M31 was generated by PCR using primers M31 cDNA 5′-3′ XhoI and M31testes 3′-5′ NheI. cDNA encoding residues 136 to 328 of swi6p was generated by PCR using primers ΔN1–135 and 3′-BamHI (see above). Following digestion with NheI, the two segments were ligated.

cDNA encoding residues 1 to 259 of swi6p was generated by PCR using primers 5′-ApaI and ΔC260–328 (see above). cDNA encoding residues 104 to 185 of M31 was generated by PCR using the primers M31 Chromobox II 5′-3′ NheI and M31 3′-5′ BamHI. Following digestion with NheI the two segments were ligated to generate swi6-M31CT.

Each swi6 cDNA mutant was fully sequenced after subcloning into the pREP81 expression vector.

Transformation of S. pombe, iodine staining, and calculation of percentage of normal asci.

The pREP81 expression plasmids containing different swi6 mutants were transformed into S. pombe protoplasts according to standard procedures (5). The transformants were incubated at 30°C on Ura− and Leu− EMM plates containing 1.2 M sorbitol and became visible after 3 to 4 days.

For the iodine staining assay, each transformant was duplicated onto EMM low nitrogen plates and an EMM master plate, again under selection of Leu− and Ura− conditions. After incubation at 30°C for 4 days, the low-nitrogen plates were exposed to iodine vapors for 3 min (6). Colonies that turn darker after exposure to iodine vapors produce a starch-like substance that reflects efficient mating-type switching. Twelve darker clones from each transformant were streaked onto fresh plates for further iodine staining and Western blotting to confirm the phenotypes and expression levels, respectively.

More than 10 individual clones from at least three different transformations were chosen for counting the percentage of normal asci. Each clone was suspended in 1 ml of EMM medium, and at least 1,000 cells were counted microscopically. The percentages were calculated (Table 1) as follows: (the number of normal asci/the number of total cells counted) × 100.

TABLE 1.

Asci formation and mitotic stability activity of swi6p mutants used in this studya

| Mutant | Iodine staining

|

% Normal asci ± SD

|

% MCLR ± SD

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonfusion | GFP fusion | Nonfusion | GFP fusion | Nonfusion | GFP fusion | |

| Controls | ||||||

| wt swi6 in pREP81 | + | +N, ±C | 70.0 ± 6.1 | 69.0 ± 6.6N | 0.35 ± 0.26 | 0.35 ± 0.23N |

| 6.0 ± 3.3C | 1.25 ± 0.35C | |||||

| pREP81 alone/GFP alone | − | − | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 3.00 ± 0.23 | ND |

| Deletions | ||||||

| ΔN1–73 | ± | + | 31.0 ± 8.8 | 25.1 ± 6.7 | 1.02 ± 0.68 | ND |

| ΔN1–135 | − | − | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 3.27 ± 0.37 | ND |

| ΔM165–236 | + | + | 60.0 ± 12.4 | 56 ± 12.4 | 0.23 ± 0.13 | ND |

| ΔC260–328 | − | − | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 4.6 ± 3.1 | 2.60 ± 0.62 | 3.00 ± 0.25 |

| ΔM141–252 | ± | ± | 20.6 ± 4.1 | ND | 1.54 ± 0.63 | ND |

| ΔC313–328 | − | − | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 4.6 ± 3.1 | 2.77 ± 0.83 | ND |

| Domain swaps | ||||||

| M31 wt | − | ND | 2.0 ± 1.4 | ND | 3.16 ± 0.20 | ND |

| M31NT-swi6 | + | ND | 50 ± 12.6 | ND | 0.89 ± 0.21 | ND |

| swi6-M31CT | − | ND | 7.5 ± 3.7 | ND | 2.58 ± 0.78 | ND |

| Mutants | ||||||

| E84 to F | + | ND | 60.0 ± 10.1 | ND | 0.59 ± 0.32 | ND |

| E74–80 to A | − | − | 12.6 ± 6.6 | 9.8 ± 3.7 | 2.24 ± 0.56 | ND |

| E74–80 to R | − | − | 8.0 ± 3.6 | 7.3 ± 2.9 | 2.97 ± 0.12 | ND |

| M91A92 to VV | + | ND | 50.0 ± 6.8 | ND | 1.43 ± 0.60 | ND |

| M91A92 to QG | − | ND | 2.8 ± 1.4 | ND | 2.48 ± 0.83 | ND |

| L101L102 to NN | − | ND | 2.6 ± 1.9 | ND | 3.44 ± 0.80 | ND |

| K103W104 to VV | − | ND | 11.0 ± 4.6 | 11 ± 3.3 | 2.93 ± 0.27 | ND |

| K103 to Q | + | ND | 61.0 ± 5.8 | ND | 1.24 ± 0.60 | ND |

| ΔNTW113–115 | − | − | 9.0 ± 4.5 | 8.0 ± 3.6 | 2.73 ± 0.80 | ND |

| W115-G | − | − | 12.0 ± 5.3 | 11 ± 4.1 | 1.79 ± 0.96 | ND |

| Y100 and Y107 to CC | − | − | 5.2 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 2.7 | 3.13 ± 0.21 | ND |

| W293 to G | − | − | 8.0 ± 2.7 | 8.1 ± 3.2 | 3.19 ± 0.29 | ND |

The second and third columns give the iodine-staining phenotypes of the swi6 deletion strain AL91 transformed with the indicated pREP81-derived plasmids. “Nonfusion” and “GFP fusion” indicate swi6p derivatives or GFP-tagged swi6p derivatives, respectively. The fourth and fifth columns give normal asci formation rates as a percentage of total cells counted microscopically for each transformant. The data are expressed as the mean ± the standard deviation from at least 10 transformed colonies. Columns 6 and 7 give the MCLR of CN91L transformants expressed as a percentage of half-sectored colonies versus the total number of colonies. +, Black colonies in the iodine-staining assay; −, mottled; ±, intermediate; N, N-terminal GFP fusion; C, C-terminal GFP fusion; ND, not determined.

Nuclear localization and subnuclear distribution of Swi6 wt and mutants.

The RSGFP4 (9) plasmid which encodes the red-shift green fluorescent protein (GFP; 714 bp, 238 amino acids) was fused to swi6p wt and mutant proteins in order to investigate nuclear localization of the proteins. The RSGFP4 open reading frame was amplified by PCR and inserted into pREP1-swi6 constructs. For N-terminal GFP fusions, i.e., GFP-swi6p wt and mutants, the RSGFP4 was amplified by PCR using the two following primers: GFP5′-3′ XhoI primer (CCGCTCGAGATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAAC) and GFP3′-5′ ApaI primer I (TCGGGGCCCTTGTATAGTTCATCCATG). For construction of GFP-ΔN1–135 fusion, the primer was the GFP3′-5′ ApaI primer II (GAGGGCCCATTTGTATAGTTCATCCAT). For construction of the GFP-ΔC260–328 fusion, the primer used was the GFP5′-3′ NheI primer (ATAGCTAGCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAAC). For construction of the swi6wt-GFP (swi6-CG) fusion, the primer used was the swi6 3′-5′ XhoI-BamHI primer (GCGGATCCCTCGAGCTCATTTTCACGGAACG968). For construction of GFP-N1–138, the primer used was the swi6 NLS 3′-5′ XhoI primer (CGTGCTCGAGTTCATCAGTTTTAC488). For the GFP-Δ236–328 fusion, the primer used was the swi6 L6 5′-3′ ApaI primer (GTGGGCCCTAGCAATGTTACTC721). For the GFP-M31 cDNA fusion, the primer used was the GFP3′-5′ SalI primer (CGTCGACTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATG). For the construction of the GFP-IVR fusion, the primers used were the IVR 5′-3′ primer (GCGGGCCCAGGAGGAAGACCAGAAC421) and the Δ260–328 deletion primer described above. Two further primers were used to verify the sequence at the junctions of swi6p and GFP: GFP69 3′-5′ primer (ATCACCATCTAATTCAACAAG) and GFP556 5′-3′ primer (AACTAGCAGACCATTATCAAC).

The pREP1-GFP fusion plasmids were transformed into strain AL91L or SP557 as described earlier. Compensation of the swi6 null mutant phenotype was evaluated by iodine staining and determining the asci percentage. For the detection of nuclear localization, the transformants were cultured overnight in selection medium. A drop of cells was placed on a slide and mounted with Citifluor containing 0.1 μg of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma). The DAPI staining and red-shift GFP were visualized by using UV light (359 nm) and blue-light excitation (470 nm), respectively. For subnuclear distribution, the GFP was detected by confocal microscopy (Bio-Rad).

MCLR assay.

We used the CN91L strain for the MCLR assay (see above for construction). The CN91L strain (h90 leu1-32 swi6::ura4-D18 ade6-704/Ch10::sup3-5) contains the swi6 null mutation, the ade6-704 mutation, and its suppressor, sup3-5, which is carried on the minichromosome, Ch10. When CN91L cells are cultured on EMM–0.15 M adenine plates, CN91L cells that retain the minichromosome give rise to white colonies, while loss of the minichromosomes gives rise to red colonies (3, 60). We used this MCLR assay to measure the activity of the swi6 mutants generated in this study.

For measurement of MCLR, CN91L protoplasts were transformed with pREP81-swi6 wt and mutant expression vectors, as described earlier. Transformants were grown on EMM (plus 1.2 M sorbitol) plates without adenine at 30°C and became visible after 3 to 4 days. Ten or more white clones of each mutant, from at least three different transformations, were picked and resuspended in EMM medium. Each suspension was subsequently plated onto EMM plates containing 12 mg of adenine per liter. After a further 3 to 4 days of incubation at 30°C, the plates were transferred to 4°C to allow the red color to deepen. The colonies with a red sector covering at least half the colony were then counted. The number of minichromosome loss events per division is the number of these half-sectored colonies divided by the total number of white colonies plus the sectored colonies and is presented as a percentage ([sectored colonies/total colonies] × 100) (3, 60). In each batch of transformations, pREP81 vector alone and pREP81-swi6 wt were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Production of monoclonal antibodies.

The swi6 coding sequence was cloned into pET25b (Novagen) in frame with a C-terminal herpes simplex virus (HSV)-His6 tag. The resulting swi6-HSV-His tag fusion protein was expressed and purified according to standard protocols (Novagen). Monoclonal antibodies were raised in a female F344 rat using the Y3Ag1.2.3 fusion partner (19). Hybridomas were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using swi6p-His tag as the antigen. One monoclonal antibody, MAC391, that specifically recognized swi6p was used in this study.

Western blotting.

For Western blots of swi6 wt and mutants, yeast transformants were cultured in 20 ml of EMM selection medium overnight at 30°C (optical density of ca. 0.2 to 0.3). Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended at a concentration of 109 cells/ml in homogenization buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5; protease inhibitor cocktail [Boehringer]; 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The cells were lysed by vortexing vigorously for 1 to 2 min with an equal volume of glass beads, followed by incubation for 5 to 10 min on ice. This was repeated five to eight times. Lysates were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes. Then, 40 μg of total protein from each sample was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) prior to electroblotting onto nitrocellulose filters. Blots were probed with monoclonal antibody MAC391 at a concentration of 1 μg/ml, and antibody binding was detected using a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled sheep anti-rat second-stage antiserum (Sigma) by using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham).

Gel overlay.

Yeast cell lysates (40 μg of protein) from AL91L, SP556, and SP557 were separated by SDS–10% PAGE and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose. After blocking overnight at 4°C, the blot was overlaid with swi6-HSV-His tag fusion protein at a concentration of 10 μg/ml at room temperature for 2 h. The wt Swi6–Swi6-HSV-His tag interaction was detected with mouse anti-HSV antibody, followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Sigma) and visualized by ECL (Amersham). As a positive control, MAC391 was used to show the presence of wt swi6p in the blot. As a negative control, the anti-HSV was used directly without prior overlay with swi6-HSV-His tag.

Purification and gel filtration of HSV-His tag proteins.

Swi6 and M31 were each expressed in the Escherichia coli BL21 with an N-terminal His tag and purified on a nickel affinity column (Novagen). M31 testes was expressed from pET25b with a C-terminal HSV-His tag and purified similarly. For swi6p, 100 μg of purified fusion protein in was loaded onto a Superose 12 HR26/60 gel filtration column (Pharmacia) in 1.0 ml of bicarbonate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.0, containing 0.5 M NaCl) and eluted with same buffer at 0.5 ml/min. For M31 and M31 testes, protein was loaded onto a Superdex 75 HR26/60 in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–100 mM NaCl–2 mM EDTA at 1 ml/min and eluted with same buffer at 5 ml/min. Molecular mass markers from 12 to 150 kDa (Pharmacia) were used to generate a standard molecular mass curve, and the swi6p, M31 and M31testes molecular masses were calculated by using that curve.

RESULTS

Assays used to measure swi6p function.

We tested the ability of a series of swi6 deletion and point mutants to complement the phenotype of a swi6 null mutant strain using three different assays. First, the sporulation phenotype of all strains was determined by exposure to iodine vapors, which detects a starch-like material that accumulates in spores (6). The amount of staining reflects the sporulation frequency, roughly indicating the efficiency of mating-type switching to the opposite allele. Accordingly, the expression of plasmid-borne wt swi6 product (swi6p) in the null mutant strain gave rise to a black phenotype, while the null mutant, transformed with the expression vector alone, gave rise to much lighter, mottled colonies. Second, the sporulation of each strain was also measured microscopically (more than 1,000 cells scored) and is presented as the percentage of cells forming normal zygotic asci: haploid cells that simultaneously express all four mating-type proteins form azygotic spores (32), which can be readily identified by microscopic examination (Table 1). Finally, mitotic stability assays (3) were undertaken to measure the ability of swi6 mutants to maintain a linear minichromosome, Ch10 (sup3-5), during colony formation (48, 60).

Functional domains of the swi6p protein.

A series of swi6p mutations containing specific deletions were constructed (Fig. 1B). These were then expressed at wt levels (Fig. 1C) on a swi6 null background to test their ability to complement the mutant phenotype (Table 1).

Deletions ΔN1–135 and ΔC260–328 in which the CD or the CSD, respectively, were deleted were inactive or possessed only residual activity in the asci formation and MCLR assays, suggesting that both of these regions are necessary for proper swi6p function (Fig. 1A and B; Table 1). The smaller N-terminal deletion, ΔN1–73, which removes the N-terminal 73-amino-acid residues immediately preceding the polyglutamic acid residues, retained substantial activity, suggesting that the key region lacking in the ΔN1–135 deletion, which is necessary for swi6p activity, encompasses the classical CD and polyglutamic acid residues. Turning to the IVR, a deletion that removes an 80-residue portion of the IVR (ΔM164–235), shortening the molecule to a size similar to that of M31, was fully functional (Fig. 1B; Table 1). However, a larger deletion (ΔM141–252) in which the CD and the CSD are more closely juxtaposed, retained only 25% of the wt activity in the asci formation and MCLR assays (Fig. 1B; Table 1). These data indicate that some spacing between the CD and the CSD is necessary for full swi6p activity. Deletion of the extreme C terminus of swi6p (ΔC312–328) resulted in an almost completely inactive protein (Fig. 1B; Table 1). This C-terminal sequence is part of the CSD and forms a predicted α-helix (2). The ΔC312–328 deletion can also explain the loss of function associated with the larger C-terminal deletion (ΔC260–328; Fig. 1B; Table 1), which includes the whole CSD. In conjunction with a site-directed mutagenesis experiment described later (W293 to G; Table 1) the ΔC260–328 and ΔC312–328 deletions confirm that an intact CSD is necessary for swi6p activity.

Western blotting confirmed that the deletion mutants expressed from pREP81 were present in yeast whole-cell extracts at a similar level to that of the wt protein in SP557 (Fig. 1C). Unfortunately, expression of ΔC260–328 and ΔC312–328 could not be tested by Western blotting because they lack the epitope recognized by monoclonal antibody MAC391. However, as shown later (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3E and F), a GFP fusion of the larger deletion, ΔC260–328, is stably expressed, suggesting that the C-terminally deleted swi6p proteins are not subject to increased proteolytic degradation.

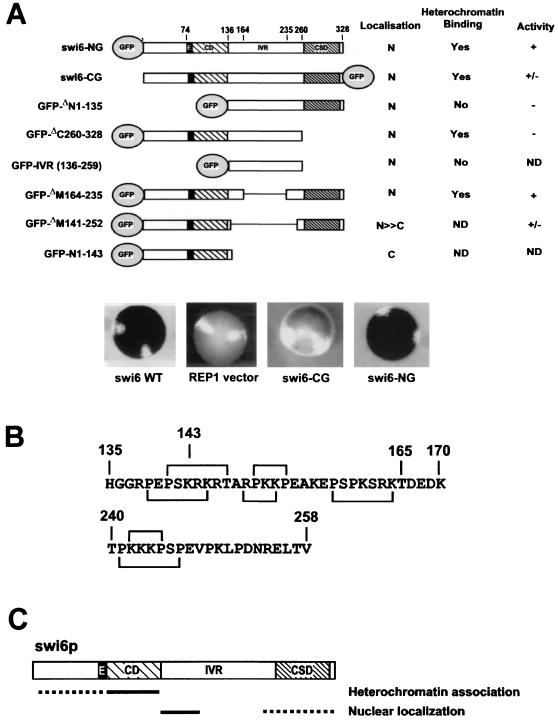

FIG. 2.

Nuclear and heterochromatin localization activities within swi6p. (A) GFP-swi6p constructs used in this study. The shaded ellipse represents the red-shifted GFP molecule fused to either the N-terminal or C-terminal end of wt swi6p or swi6p deletion mutants. N, nuclear distribution; C, cytoplasmic localization; ND, not determined. The iodine-staining phenotype of the N- and C-terminal GFP fusions is shown below. (B) Predicted nuclear localization motifs within the swi6p amino acid sequence. Longer square brackets, SV40 NLS-like seven-residue motifs; shorter brackets, four-residue motifs. (C) Summary of nuclear and heterochromatin binding data.

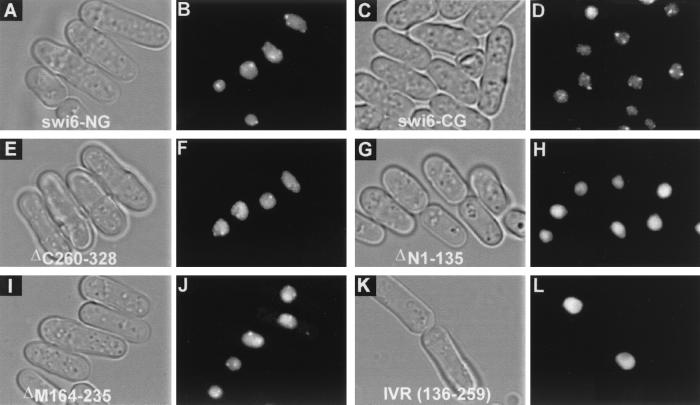

FIG. 3.

Subnuclear localization of swi6p-GFP fusion proteins in swi6 null cells. (A, C, E, G, I, and K) Phase-contrast images. (B, D, F, H, J, and L) GFP signal. Panels A and B show that the swi6-NG fusion localizes to specific subnuclear sites within the nucleus. Panels C and D show that swi6-CG fusion localizes to specific subnuclear sites with the nucleus. Panels E and F show that GFP-ΔC260–328 fusion localizes to specific subnuclear sites with the nucleus. Panels G and H show that the GFP-ΔN1–135 fusion localizes to the nucleus but does not localize to specific subnuclear sites within the nucleus. Panels I and J and show that the GFP-ΔM164–235 fusion localizes to specific subnuclear sites with the nucleus. Panels K and L show that the GFP-IVR localizes to the nucleus but not to specific subnuclear sites.

We also noted that wt swi6p runs at approximately 50 kDa in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C), slower than its predicted mass of 37, kDa calculated from the primary sequence. Notably, bacterially expressed HSV-tagged swi6p also runs slowly (at approximately 52 kDa; data not shown).

The failure of certain deletion mutants to complement the swi6 null strain could reflect one or more deficiencies, such as an inability of mutants to interact with other proteins or mislocalization of mutant proteins within the cell. Since no direct interactor of swi6p has yet been described, we have examined the second possibility using GFP fusion constructs of the deletion mutants (Fig. 2). This analysis has also allowed us to localize heterochromatin binding and nuclear localization functions within swi6p.

The heterochromatin-binding domain of swi6p is in the N-terminal region.

As a measure of heterochromatin binding, we compared the distribution of the swi6p-GFP constructs with the pattern observed for endogenous swi6p. swi6p localizes to subnuclear spots within interphase nuclei (14), which represent the blocks of heterochromatin associated with the chromosomes and can vary in number from one to three depending on associations that lead to larger chromocenters. In an initial experiment, we observed that both GFP-swi6p (swi6-NG) and swi6p-GFP (swi6-CG) (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3A to D) localized to the endogenous swi6p spots, confirming that fusion of swi6p to GFP per se does not disrupt subnuclear localization.

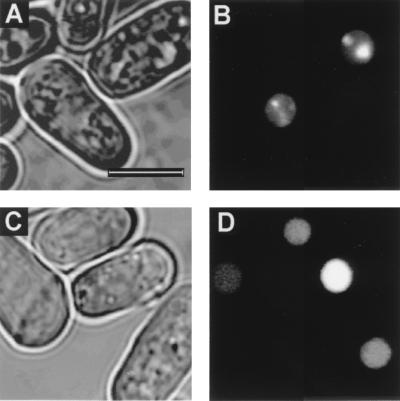

We have localized the swi6p heterochromatin-binding sequence to the N-terminal 135 amino acids of the molecule. The evidence comes from four GFP-fusions (Fig. 2 and 3). First, the GFP-ΔN1–135, in which the N-terminal region, including the CD, is deleted localized to the nucleus of swi6 null cells but was not concentrated at heterochromatic sites normally occupied by wt swi6p (Fig. 3G and H). Second, a GFP fusion of the CSD deletion (ΔC260–328) localized to the heterochromatic sites (Fig. 3E and F). Third, the ΔM164–235 deletion (Fig. 3) also localized to the heterochromatic sites (Fig. 3I and J). Finally, on the null mutant background, the GFP-IVR fusion (GFP-136–259) which lacks the N1–135 region, localized to the nucleus but not to heterochromatic sites (Fig. 3K and L). It would seem from these data that swi6p contains a single N-terminal heterochromatin-binding domain, unlike Drosophila HP1, where both N- and C-terminal HP1 fusions have been shown to localize to heterochromatin-binding domains (51). However, this difference between Drosophila HP1 and swi6p may be explained by another observation where the GFP-ΔN1–135 fusion was shown to localize to heterochromatic foci but on a swi6 wt background (Fig. 4B). The simplest explanation for this result is that the C-terminal GFP-ΔN1–135 fusion is recruited to the heterochromatic foci via an interaction with endogenous wt swi6p. Since the Drosophila experiments were also done on a wt background (51), the C-terminal HP1 fusion may also have been recruited to heterochromatin through an interaction with endogenous HP1.

FIG. 4.

Localization of GFP-ΔN1–135 in wt and swi6 null cells. (A and C) GFP signal. (B and D) Phase-contrast images. The scale bar in panel A represents 5 μM. Panels A and B show expression of the GFP-ΔN1–135 fusion on a wt background. The fusion protein localizes to bright heterochromatic foci. Panels C and D show expression of the GFP-ΔN1–135 fusion on the null mutant background. The fusion protein is distributed evenly throughout the nucleus.

The activities of the GFP-tagged swi6p fusions in all three assays mirrored those of the nonfusion partners, except for swi6-CG, which was unable to complement the swi6 null mutation (Fig. 2A; Table 1). The result with swi6-CG lends support to the conclusion drawn with the ΔC313–328 deletion (Fig. 2A; Table 1), in that the amino acids at the extreme C-terminal of swi6p are essential for full activity.

A strong NLS resides in the IVR of swi6p.

The observation that deletion mutants ΔN1–135 and ΔC260–328 both localize to the nucleus suggests that the IVR, which they share, contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS). This was confirmed directly by the nuclear localization of a further GFP construct, GFP-IVR (GFP-136–259) (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3K and L). The nuclear targeting function was more precisely defined by the GFP-ΔM164–235 deletion, which also localizes to the nucleus (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3I and J), indicating that the NLS in the IVR resides either in the interval from positions 136 to 163 or in the interval from positions 236 to 259. Interestingly, the computer program PSORTII (28, 45) revealed that both of these regions contain matches to the four- and seven-residue nuclear localization motifs of the simian virus 40 (SV40) type (10). As shown in Fig. 2B, two overlapping seven- and four-residue motifs fall within the segment from positions 136 to 163 of swi6p, a finding consistent with this region having a strong nuclear localization function. In addition, one seven- and one overlapping four-residue pattern also exist between residues 241 and 247. We searched the rest of swi6p for other NLSs by introducing a GFP fusion in which the IVR was deleted (GFP-ΔM141–252). We found that the GFP-ΔM141–252 localized mainly, though not exclusively, to the nucleus (Fig. 2A; data not shown) supporting the existence of an additional, weaker NLS. An N-terminal construct, GFP-N1–143 (Fig. 2A; data not shown) localized to the cytoplasm, suggesting that this second nuclear localization activity lies C-terminal to residue 252. No matches to the consensus NLS sequences were found in this C-terminal region.

CD function is conserved from yeasts to humans.

We have previously shown, using zooblots, that the CD motif is conserved in a variety of animal and plant species (58). We have directly tested the functional conservation of the CD through a domain-swap experiment in which the swi6p CD was replaced by the M31 CD (M31NT-swi6; Fig. 5A). When expressed at levels similar to that of endogenous swi6p (Fig. 5B), the chimeric protein could almost fully complement the swi6 null mutation (approximately 70 and 80% of the wt activity in asci formation and MCLR assays, respectively; Fig. 5 and Table 1). By contrast, when the CSD of swi6p was substituted by the M31 CSD (swi6-M31CT; Fig. 5A) only residual activity was obtained (Table 1). Expression of full-length M31 also failed to complement the null phenotype (Fig. 5; Table 1), although GFP-M31 was found to localize to heterochromatin (data not shown). These data indicate that classical CD function is likely to be conserved across species, while the CSD appears to retain a species-specific function.

FIG. 5.

swi6p-M31 domain swap constructs. (A) Construction of domain-swap mutations. The activities of the wt and domain-swap constructs are summarized on the right, and the iodine-staining phenotypes of the mutants are shown below. (B) Western blot showing expression of wt and domain-swap swi6 mutants. Except for the wt swi6 strain SP557 (lane 1), all lanes correspond to swi6 deletion strain AL91L transformed with the following pREP81-constructs: lane 2, M31NT-swi6; lane 3, swi6-M31CT; and lane 4, wild-type M31. swi6p was detected with monoclonal antibody MAC391; swi6-M31CT and M31 were detected with anti-M31 monoclonal antibody MAC353 (65).

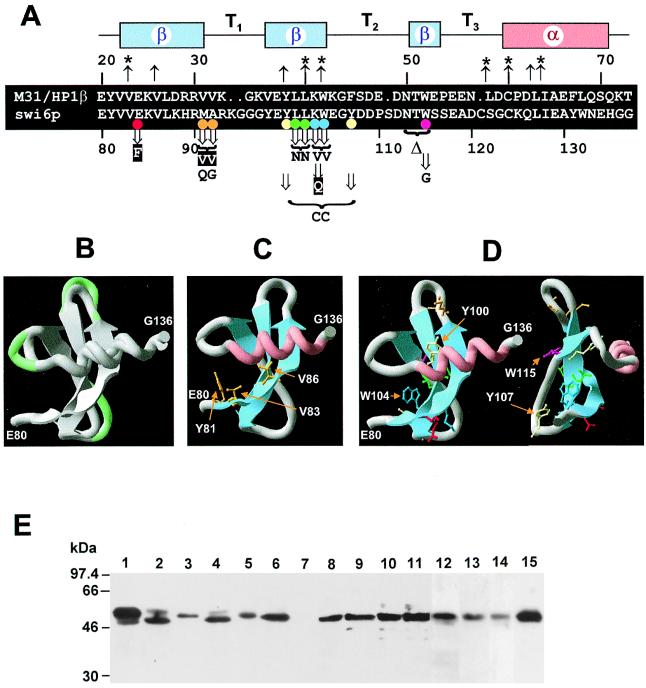

Modeling the swi6p CD on the three-dimensional structure of the M31 CD.

Given the functional equivalence of the M31 and swi6p CDs and their high degree of sequence similarity, it is likely that they adopt a similar three-dimensional conformation. The solution structure of the M31 CD was recently solved and consists of a three-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet folded against a C-terminal α-helix (4) (see Fig. 6A and B). Residues contained in the β-strands of the M31 CD are particularly well conserved with the equivalent residues in swi6p (73% identity and 89% similar residues; Fig. 6A). In contrast, residues corresponding to the turns between the β-strands are less similar, and it is here that gaps must be introduced into the M31 sequence to maintain the alignment with swi6p (Fig. 6A). Given the above findings, we modeled the swi6p CD on the M31 CD NMR structure using the SWISS-MODEL and Swiss PDB-Viewer programs (23, 24) (Fig. 6B to D). The primary difference between the modeled swi6p structure and the M31 NMR structure is, as anticipated, in the turns (T1 to T3), which are longer in swi6p (Fig. 6A). We also note that the amino acids in swi6p that immediately follow the β-pleated sheet favor the formation of an α-helix, like M31, despite several differences between the swi6p and M31 sequences in this region.

FIG. 6.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the swi6p CD. (A) Alignment of the CDs of M31 and swi6p showing the secondary structure arrangement above. Up arrows, residues contributing to the hydrophobic core of the M31 structure (those with asterisks line the hydrophobic cleft on the surface of the β-sheet) (4). Down arrows, site-directed mutants generated in this study (residues shown below represent substitutions). A white character on a black background indicates a mutation that retains activity; inactive substitutions are indicated by black letters. Colored circles, key for amino acid side chains shown in panel D. (B) M31 CD (residues 20 to 72) and modeled swi6p CD (residues 80 to 136) three-dimensional structure shown superimposed in “ribbon” format. In the turns T1 to T3 the swi6p chain is shown in green. (C) Modeled swi6p CD showing the side chains of residues where equivalent mutation in HP1 or Pc affects gene silencing. (D) swi6p mutations employed in this study. In the righthand part of the figure the CD has been rotated through 45° about a vertical axis. (E) Western blot showing expression of wt and site-directed mutants of swi6p. Except for wt swi6 strain SP557 (lane 1), all lanes correspond to swi6 deletion strain AL91L transformed with the following pREP81-constructs: lane 2, E74–E80→R; lane 3, K103W104-VV; lane 4, ΔN113–W115; lane 5, W115-G; lane 6, Y100Y107-CC; lane 7, AL91 (swi6 deletion strain); lane 8, E94-F; lane 9, K103-Q; lane 10, M91A92-VV; lane 11, L101L102-NN; lane 12, M91A92-QG; lane 13, W239-G; lane 14, E74–E80→A; 15, wt swi6p.

Mutational analysis of the swi6p CD.

Using the information obtained from the modeled swi6p CD, we undertook a mutational analysis of the conserved residues within and adjacent to the CD. The effects of the site-directed mutants on swi6p activity were measured by using the three functional assays described above (Table 1). Our initial experiment addressed the function of the stretch of negatively charged amino acids immediately adjacent to the CD (Fig. 1A). Previous studies with Drosophila HP1 (50) have shown that three of the six glutamic acid residues can be replaced by alanine, with no effect on function in vivo (E78 to E80 to A, using swi6p numbering; Table 2). However, we found that a more extensive replacement of all seven residues with either alanine (E74 to E80 to A) or arginine (E74 to E80 to R), abolished the ability of swi6p to complement the swi6 null phenotype (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of CD mutational dataa

| CD protein | Equivalent position in swi6 | Consensus residue | Mutation | Activity | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP1 | E78–E80 | − | EEE-AAA | Yes | 50 |

| swi6 | E74–E80 | − | EEEEEDE-AAAAAAA | Residual | This study |

| swi6 | E74–E80 | − | EEEEEDE-RRRRRRR | Residual | This study |

| HP1 | Y81 | Y% | Y-F | No | 50 |

| HP1 | V83 | V∗ | V-M | No | 50 |

| swi6 | E84 | − | E-F | Yes | This study |

| Pc | V86 | ∗ | I-F (Pc106) | No | 41 |

| HP1 | H89R90 | + | RR-QQ | Yes | 50 |

| swi6 | M91A92 | ∗∗ | MA-VV | Yes | This study |

| swi6 | M91A92 | ∗∗ | MA-QG | No | This study |

| HP1 | K94 | + | K-Q | Yes | 50 |

| swi6 | Y100Y107 | Y% | YY-CC | No | This study |

| swi6 | L101L102 | L% | LL-NN | No | This study |

| swi6 | K103W104 | +W | KW-VV | No | This study |

| swi6 | K103 | + | K-Q | Yes | This study |

| clr4 | W104 | W | W-G | Partial | 29 |

| clr4 | W115 | W | W-G | Partial | 29 |

| swi6 | W115 | W | W-G | Residual or partial | This study |

| swi6 | N113–W115 | N(T/S)W | Deletion | Residual | This study |

| Pc | I128–D129 | ∗0 | Deletion (PcXL5) | No | 41 |

+, Conserved basic residues; −, conserved acidic residues; ∗, conserved hydrophobicity; %, semiconserved hydrophobicity; 0, no clear conservation. For the activities of mutants used in this study, “yes” corresponds to >50% wt activity, “partial” corresponds to 20 to 50% wt activity, “residual” corresponds to 10 to 20% wt activity, and “no” corresponds to <10% wt activity in asci formation and MCLR assays (see Table 1).

Studies in Drosophila have shown that conserved residues within and adjacent to the first β-strand are important for CD function (41). For example, the conserved hydrophobic residues Y81, V83, and V86 (using the numbering of swi6p CD; Fig. 6C) are important for CD function. In order to provide a more complete picture, we have extended this analysis using site-directed mutagenesis to change a panel of amino acid residues within the swi6p CD β-sheet (Fig. 6A). Beginning at the N terminus of the first strand, the highly conserved residue E84 was changed to F. Surprisingly, the E84-F substitution did not significantly affect swi6p activity (Tables 1 and 2).

The C terminus of the first β-turn is occupied by the sequence M91A92 in the modeled swi6p structure (Fig. 6A and D). These residues are typical of those found in this position, which are generally nonpolar in nature (Table 2). For example, the corresponding residues in M31 are V31V32 (Fig. 6A). Thus, as might be expected, substituting the swi6 sequence M91A92 for the M31 equivalent, VV, resulted in a protein that retained most or all of its activity (Tables 1 and 2). However, the nonconservative substitution M91A92-QG (similar size residues, different degree of polarity), resulted in an inactive protein (Tables 1 and 2).

In addition to Y81, four other positions are invariantly occupied by aromatic hydrophobic residues in the CD of HP1 proteins. These correspond to Y100, W104, Y107, and W115 in swi6p (Fig. 6A and D; Table 2). Substitution of Y100 and Y107 with cysteine residues resulted, not unexpectedly, in a loss of swi6p activity. This loss of function is most likely due to the change in Y100, which lies in the middle of the second β-pleated sheet, rather than the change in Y107, which lies in the bend that follows this sheet (Fig. 6D). Two further substitutions, L101L102-NN and K103W104-VV (Fig. 6A), that are in the second β-sheet also disrupted function (Tables 1 and 2). In the second case, the loss of activity is probably due to the conserved tryptophan residue at position 104, since a K103-Q substitution alone did not seriously affect activity (Fig. 6A; Tables 1 and 2). The equivalent W104 residue in clr4p has also been shown to be essential for function (29).

Deletions and substitutions in the third β-strand also disrupt function. In particular, deletion of the highly conserved triplet of amino acids (i.e., N113T114W115) resulted in an almost complete loss of swi6p activity. Mutation of the highly conserved tryptophan residue at position 115 to glycine (115W-G; Fig. 6A and D) leads to a significant reduction of function (Tables 1 and 2). This tryptophan residue is conserved in all HP1-like chromo domains (30), and modeling of its aromatic side chain reveals that it lies behind the β-sheet (Fig. 6D).

We have also made one substitution within the swi6p CSD. W293 is almost invariant among HP1 proteins (in D. melanogaster and D. virilis HP1 proteins the equivalent position is occupied a conservative F residue [8]). A W293-G substitution resulted in loss of complementation (Table 1) and confirms that an intact CSD is necessary for swi6p activity.

The inactivity of the site-directed mutants described above does not appear to be due to protein instability or poor expression, since cell extracts revealed levels of mutant proteins that were similar to those found for swi6p in SP557 (Fig. 6E). We also obtained the same degree of complementation with expression of swi6p wt, and mutants from the higher-expressing pREP1 promoter (data not shown).

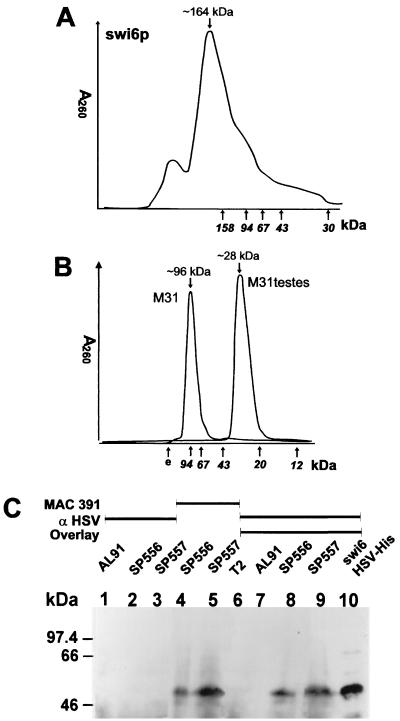

swi6p self-association.

When bacterially expressed swi6 fused to an N-terminal His tag (His-swi6p) was subjected to gel filtration chromatography under native conditions, the majority of the protein eluted in a peak corresponding to an apparent molecular mass of 164 kDa (Fig. 7A). This is almost exactly four times the predicted monomer molecular mass of His-swi6p (40 kDa). Similarly, when purified His-M31 was loaded on a gel filtration column the protein eluted with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 96 kDa (Fig. 7B), again a value almost exactly four times the predicted monomer molecular mass of the His-tagged fusion protein (26 kDa). We also determined the molecular mass of a naturally occurring isoform of M31, M31testes, which lacks the C-terminal 85 amino acid residues of full-length M31 (49). M31testes-HSV-His6 eluted with a molecular mass of approximately 28 kDa (Fig. 7B), twice the predicted monomer mass (14 kDa). Dimerization of M31testes was also observed using electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy, in which the major molecular weight species of 28,083.36 ± 2.33 was observed in H2O (pH 7.0). In dilute formic acid (denaturing buffer) the major M31testes species had a molecular weight of 14,042 ± 1.29, which is the monomer.

FIG. 7.

Swi6p quaternary structure. (A) Superose 12 HR26/60 chromatogram of swi6p-HSV-His tag. Elution of markers is shown on the horizontal axis. (B) Superdex 75 HR26/60 FPLC profiles of M31-HSV-His tag and M31testes-HSV-His tag. (C) Gel overlay experiment. The cell lysates indicated were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Lanes 6 to 10 were incubated with HSV epitope-tagged swi6p before the membrane was probed with the antibodies shown (see Materials and Methods). AL91 and T2 are swi6 deletion strains, SP556 and SP557 are swi6 wt strains. Lane 10 contains purified recombinant swi6-HSV-His protein.

We confirmed the self-association of swi6p with gel overlay experiments. HSV-His-swi6p was used to probe blots of electrophoretically separated cell extracts from wt (SP557) and swi6 null mutant (AL91L) cells. After incubation with HSV-His-swi6p, the blots were probed with a commercially available antibody to the HSV tag. The antibody detected binding of HSV-His-swi6p to a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 50 kDa in extracts derived from wt SP557 cells. This finding is consistent with the mobility of endogenous swi6p under conditions of SDS-PAGE. The antibody did not detect anything in the extracts derived from the null mutant strain AL91L (Fig. 7C).

DISCUSSION

We have undertaken a structure-function analysis of swi6p, an HP1-like protein in S. pombe (38). Like Drosophila HP1 (13) and M31 in mice (17, 65), swi6p is localized predominantly within heterochromatin domains which, in S. pombe, are found at the centromeres, silent mating-type loci, and telomeres. Swi6p is involved in silencing at these loci (14, 33) and, in addition, cells lacking swi6p exhibit an increased rate of chromosome loss (3), suggesting that swi6p, like HP1 in Drosophila (31), is required for efficient chromosome segregation. Thus, HP1-like proteins appear to be functionally as well as structurally conserved between fission yeast and metozoans.

Conservation of CD function.

The close sequence similarity and functional conservation of the CDs of M31 and swi6p prompted us to model the three-dimensional structure of the swi6p CD on the recently solved M31 structure. We then used the modeled swi6p structure to complete a detailed structure-function analysis of the CD using the advantages of the yeast system. In particular, we have extended initial findings using Drosophila Pc and HP1, which identified residues within the CD that are important for function (41). Previously, mutations in three hydrophobic residues have been shown to disrupt function in Drosophila HP1 or Pc: Y24-F(HP1), V26-M (corresponding to the su(var)2-502 mutation) (50), and I31-F (corresponding to the pc106 mutation) (41). The V26-M (HP1) and I31-F (Pc) mutations map to residues V83 and V86 in the swi6p CD (Fig. 6C), both of which contribute to the hydrophobic core of modeled domain. HP1 Y24-F maps to the swi6p residue Y81, which sits at the edge of the hydrophobic groove formed between the β-sheet and the α-helix (Fig. 6C). While substitutions of amino acids in the hydrophobic core of the domain might be expected to affect its folding, the loss of function associated with the Y24-F might instead interfere with interactions of the CD with other proteins, as proposed by Ball et al. (4).

Mutations at the C terminus of the first β-strand (M91A92 to QG) and within the second strand (Y100 to C, L101L102 to NN, and W104 to V) all disrupt swi6p function (Table 1). Notably, Y100, L101L102, and W104 are part of the hydrophobic core of the modeled swi6p CD, with W104 lying at the bottom of the hydrophobic groove (Fig. 6A and D). These mutations may interfere with the CD fold, although the exposed position of W104 in the groove (Fig. 6D) suggests that it could also be involved in protein-protein interactions. Changing the highly conserved hydrophobic residue W115 to G (Fig. 6D; Table 2), which lies in the third strand, also leads to a loss in swi6p activity. However, our modeled swi6p structure shows the side chain of W115 projecting backwards away from the surface of the β-sheet (Fig. 6D). This is also true for corresponding W52 residue in M31 (Fig. 6A) (4). Hydrophobic residues in the C-terminal α-helix are also likely to be important as evidenced by the pcXL5 deletion, which removes residues I69D70 in the Pc protein and leads to a loss of function (Table 2) (41). Pc I69 corresponds to I128 in swi6p, which lies at the top of the hydrophobic groove. Two changes in the β-sheets that do not affect swi6p activity are the E84-F and K103-Q substitutions in the first and second strands, respectively (Fig. 6A; Table 1). Likewise, a Drosophila mutation in the first strand, which is equivalent to a H89R90-QQ substitution in swi6p, also has little effect on HP1 activity (50) (Table 2). This is surprising since these residues are part of the highly conserved β-sheets (Fig. 6A and B; Table 2). However, these results are consistent with the rule that substitutions in hydrophobic residues that form the core are most likely to affect CD function.

Functional organization of HP1 proteins.

Our deletion analysis has revealed the functional organization of swi6p and has identified constraints on the organization of the molecule. Residues N-terminal of the acidic amino acid stretch are largely dispensable, but the CD and an intact CSD are necessary for activity (Fig. 1B; Table 1). Shortening of the IVR is compatible with activity, but some spacing between the CD and the CSD is required. Another constraint concerns the stretch of acidic residues adjacent to the N terminus of the CD. This typically consists of six or seven glutamic acid residues and is a characteristic of HP1 proteins (30). Negatively charged residues seem to be required at this point in the molecule, since substitution of the entire acidic stretch with alanine or lysine in swi6p results in a loss of activity (Tables 1 and 2). A smaller substitution of three of the residues with alanine in Drosophila HP1 does not seriously affect activity (50). The function of this stretch of negatively charged amino acids is unknown, although it has been suggested that this region might interact with the lysine-rich histone tails (58), whose positive charge can be regulated by acetylation (22).

Our observation that neither M31 nor swi6-M31CT complement the swi6 null mutation (Fig. 5; Table 1) suggests that sequence differences between HP1 proteins mediate species-specific functions. The extreme C terminus, for example, is required for swi6p activity and could mediate species-specific protein interactions (Fig. 1; Table 1). The C termini of CD proteins appear to be important for such interactions. In Pc-like proteins a C-terminal Pc-box mediates interactions with other Polycomb-group members, such as Ring1A (56). The positioning of NLSs within HP1 proteins also differs. In swi6p, the IVR contains a strong nuclear localization activity with a second, albeit weaker, activity in the C-terminal region encompassing the CSD (Fig. 2B). The strong NLS coincides with a cluster of SV40 NLS-like motifs (Fig. 2B). Drosophila HP1 contains a nucleoplasmin-like bipartite NLS motif (10, 53) in the region between the CD and CSD. However, the nuclear targeting activity of Drosophila HP1 is reported to lie C terminal to its IVR (51). Differences may also exist in the heterochromatin-binding activities. In swi6p, heterochromatin targeting sequences reside solely in the N-terminal region that includes the CD (Fig. 2). This differs from the findings of Powers and Eissenberg (51), who reported that a C-terminal portion of Drosophila HP1 (residues 95 to 206) contains both nuclear localization and heterochromatin binding activities. It was also shown that a heterochromatin binding activity resides within the HP1 CD when the N terminus was provided with an NLS (50). These findings in Drosophila can be reconciled with ours if, after transport of the C-terminal portion into the nucleus, targeting to heterochromatin results from the formation of heterocomplexes with wt HP1 present in the cells via a CSD-CSD interaction (see below). Consistent with this interpretation, we have found that on a wt swi6 background, but not in swi6 null cells, GFP-tagged swi6p constructs lacking the CD are recruited to heterochromatin (Fig. 4B).

Self-association of HP1 proteins.

The notion that heterochromatin consists of a macromolecular protein complex is based on the characterization of variegating position effects (21, 25, 52). In a prescient mathematical model for the assembly of heterochromatin complexes, Tartof et al. suggested that oligomers of certain components would be incorporated into the complex (61). Consistent with the model, the data presented suggest that HP1 proteins can form oligomers through self-association. (i) Under nondenaturing conditions, swi6p and M31 both eluted from fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) gel filtration columns with a molecular weight four times that of the respective monomers (Fig. 7A and B). (ii) The N-terminal 100 amino acid residues of M31 behave as a dimer as seen by mass spectroscopy under nondenaturing conditions and in gel filtration experiments (Fig. 7B). (iii) M31 has been shown to self-associate in yeast two-hybrid screens (35). (iv) Self-association of swi6p in vitro can also be demonstrated in gel overlay experiments (Fig. 7C).

What are the protein interfaces involved in self-association of HP1-like proteins? Our own data using M31testes suggest that residues in the N-terminal half of M31, possibly involving the CD, are likely to be involved in self-association (Fig. 7B). This idea is consistent with the observation that an N-terminal CD-containing fragment of HP1α forms dimers under nondenaturing conditions (66). However, we note that a smaller N-terminal fragment of M31 (amino acids 10 to 80) used for the NMR studies was found to be monomeric by mass spectroscopy (4). Taken together, these data suggest that self-association of HP1-like proteins involves an N-terminal region that includes the minimal CD used in the NMR studies.

Since full-length M31 and swi6p appear to form higher-molecular-weight oligomers (Fig. 7A and B), a further self-interaction interface is likely to reside in the C-terminal region of the protein. Consistent with this, the CSDs of human HP1α and Drosophila HP1 have been shown to self-interact in vitro (59, 68). Moreover, it has recently been shown that a number of proteins that interact with HP1 contain a conserved pentapeptide motif, which is present in the CSD of HP1 proteins themselves (59), suggesting a structural basis for the observed CSD-CSD self-interactions. Based on these findings, we suggest that HP1 proteins form oligomers through CSD-CSD interactions and through interactions involving an N-terminal region that includes the CD (Fig. 8A and B).

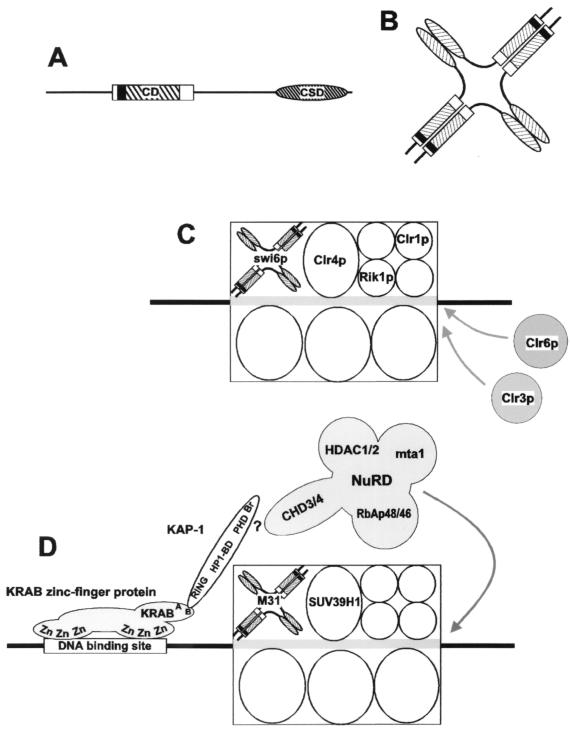

FIG. 8.

Possible models for incorporation of swi6p and M31 into heterochromatin complexes. (A) Modular structure of swi6p. The CD and CSD are shown as a hatched rectangle or ellipse, respectively, and the hinge region or IVS joining them is shown as a black line. The acidic region adjacent to the CD is also indicated. (B) One possible oligomeric configuration of swi6p involving dimerization of monomers through the CSD and the association of dimers to form a tetramer. (C) Model for the organization of swi6p-containing heterochromatin-like complexes. The stoichiometry and spatial relationship of components within the complex are unknown. The thick gray line running through the complex represents nucleosomes deacetylated (arrows) by clr3p and clr6p. (D) A model for the recruitment by KRAB zinc-finger proteins of M31 into local heterochromatin-like complex. The stoichiometry and spatial relationship of components within this complex are also unknown.

Heterochromatin-like complexes as a conserved mechanism of gene regulation.

We suggest that it is as oligomers that HP1 proteins are incorporated into heterochromatin-like complexes. Accordingly, we have modeled the incorporation of a swi6p oligomer into a heterochromatin-like complex that represses the donor mating-type loci (Fig. 8C). We envisage the swi6p oligomer as part of a core complex, that is, a repeating unit, similar to the repeating SIR complex in budding yeast that can assemble chromosomal DNA into a repressed domain (22). Oligomerization of swi6p is likely to be driven by the high local concentrations within heterochromatic foci (Fig. 3A and B). This may be analogous to the way that spectrin oligomers (43) are thought to be assembled at the red blood cell membrane from spectrin dimers and tetramers (37), a process that is promoted by high local concentrations and interactions with other proteins, e.g., ankyrin (43). Likewise, oligomerization of swi6p may be promoted by interaction with other constituents of the core complex, such as clr1p, clr4p, and rik1 (Fig. 8C): clr4p and rik1p are required for incorporation of swi6p into the heterochromatin complexes at the centromeres, telomeres, and the mat2-K-mat3 loci (15). Two further proteins that are required for repression at the silent mating-type loci, clr3p and clr6p, share considerable homology with histone deacetylases, suggesting that silencing of the donor loci involves histone deacetylation (20). This model for silencing of the donor mating-type loci is similar to that proposed for KRAB-ZFP (Krüppel-associated box-zinc finger protein)-mediated repression in mammals (Fig. 8D) (54) in which the KAP-1 corepressor recruits a heterochromatin-like complex through a KAP-1–CSD interaction (54). The recruited complex includes SUV39H1 (a human homologue of clr4p), which is immunoprecipitated as part of the same chromatin fraction as M31 (1). Recent work also suggests that assembly of a heterochromatin-like complex by KAP-1 is associated with histone deacetylation (46). This finding is consistent with the observation that CHD3 protein, which is a component of the NuRD deacetylase complex, interacts with KAP-1 (54).

Although further work needs to be done to generalize our findings, it would seem that both the enzymatic and structural components involved in the assembly of heterochromatin-like complexes are highly conserved. The localized assembly of such complexes may provide an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for regulating gene activity (58).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Maundrell for the pREP1, A. M. Carr for pREP81 expression vectors, and M. Yanagida for the CN2 strain. We thank G. W. Butcher and A. Hutchings for help with monoclonal antibody production, J. Mellor for help with production and verification of the strains used in this study, M. Fricker and D. Spiller for help with confocal microscopy, J. Coadwell for initial structural analysis of swi6p, and J. P. Brown for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was funded by BBSRC grant LRG43/AO1809.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aagaard L, Laible G, Selenko P, Schmid M, Dorn R, Schotta G, Kuhfittig S, Wolf A, Lebersorger A, Singh P B, Reuter G, Jenuwein T. Functional mammalian homologues of the Drosophila PEV-modifier Su(var)3-9 encode centromere-associated proteins which complex with the heterochromatin component M31. EMBO J. 1999;18:1923–1938. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aasland A, Stewart A F. The chromo shadow domain, a second chromo domain in heterochromatin-binding protein 1, HP1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3168–3173. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allshire R C, Nimmo E R, Ekwall K, Javerzat J P, Cranston G. Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains of fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:218–233. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball L J, Murzina N V, Broadhurst R W, Raine A R C, Archer S J, Stott F J, Murzin A G, Singh P B, Domaille P J, Laue E D. Structure of the chromatin binding (chromo) domain from mouse modifier protein 1. EMBO J. 1997;32:2473–2481. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beach D, Piper M, Nurse P. Construction of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene bank in a yeast bacterial shuttle vector and its use to isolate genes by complementation. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;187:326–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00331138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bresch C, Muller G, Egel R. Genes involved in meiosis and sporulation of a yeast. Mol Gen Genet. 1968;102:301–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00433721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown K E, Baxter J, Graf D, Merkenschlager M, Fisher A G. Dynamic repositioning of genes in the nucleus of lymphocytes preparing for cell division. Mol Cell. 1999;3:207–217. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark R F, Elgin S C R. Heterochromatin protein 1, a known suppressor of position-effect variegation, is highly conserved in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6067–6074. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.22.6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delagrave S, Hawtin R E, Silva C M, Yang M M, Youvan D C. Red-shifted excitation mutants of the green fluorescent protein. Biotechnology. 1995;13:151–154. doi: 10.1038/nbt0295-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dingwall C, Laskey R A. Nuclear targeting sequences—a consensus? Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:478–481. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90184-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doe C L, Wang G, Chow C, Fricker M D, Singh P B, Mellor E J. The fission yeast chromo domain encoding gene chp1(+) is required for chromosome segregation and shows a genetic interaction with alpha-tubulin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4222–4229. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.18.4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eissenberg J C, Elgin S C R. Boundary functions in the control of gene expression. Trends Genet. 1991;7:335–340. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90424-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eissenberg J C, James T C, Hartnett-Foster D M, Hartnett T, Ngan V, Elgin S C R. Mutation in a heterochromatin-specific chromosomal protein is associated with suppression of position effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9923–9927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekwall K, Javerzat J P, Lorentz A, Schmidt H, Cranston G, Allshire R C. The chromodomain protein Swi6: a key component of fission yeast centromeres. Science. 1995;269:1429–1431. doi: 10.1126/science.7660126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekwall K, Nimmo E R, Javerzat J P, Borgstrom B, Egel R, Cranston G, Allshire R. Mutations in the fission yeast silencing factors clr4+ and rik1+ disrupt the localisation of the chromo domain protein Swi6p and impair centromere function. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2637–2648. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.11.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein H, James T C, Singh P B. Cloning and expression of Drosophila HP1 homologs from the mealybug, Planococcus citri. J Cell Sci. 1992;101:463–474. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.2.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Festenstein R, Sharghi-Namini S, Fox M, Roderick K, Tolaini M, Norton T, Saveliev A, Kioussis D, Singh P B. Heterochromatin protein 1 modifies mammalian PEV in a dose- and chromosomal-context-dependent manner. Nat Genet. 1999;23:475–461. doi: 10.1038/70579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franke A, Messmer S, Paro R. Mapping functional domains of the Polycomb protein of Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosome Res. 1995;3:351–360. doi: 10.1007/BF00710016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galfre G, Milstein C. Rat x rat hybrid melanomas and a monoclonal anti-Fd portion of mouse IgG. Nature. 1979;277:131–133. doi: 10.1038/277131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grewal S I S, Bonaduce M J, Klar A J S. Histone deacetylase homologs regulate epigenetic inheritance of transcriptional silencing and chromosome segregation in fission yeast. Genetics. 1998;150:563–576. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.2.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grigliatti T. Position-effect variegation—an assay for nonhistone chromosomal proteins and chromatin assembly and modifying factors. In: Hamkalo B A, Elgin S C R, editors. Functional organization of the nucleus: a laboratory guide. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 587–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guex N, Diemand A, Peitsch M C. Protein modelling for all. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:364–367. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guex N, Peitsch M C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henikoff S. A pairing-looping model for position effect-variegation in Drosophila. In: Gustafson J P, Flavell R B, editors. Proceedings of the 22nd Stadler Genetics Symposium. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press, Inc.; 1995. pp. 211–242. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henikoff S. Conspiracy of silence among repeated transgenes. Bioessays. 1998;20:532–535. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199807)20:7<532::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horton P, Nakai K. A probabilistic classification system for predicting the cellular localization sites of proteins. Intellig Syst Mol Biol. 1996;4:109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivanova A V, Bonaduce M J, Ivanov S V, Klar A J. The chromo and SET domains of the Clr4 protein are essential for silencing in fission yeast. Nat Genet. 1998;19:192–195. doi: 10.1038/566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones D O, Cowell I G, Singh P B. Mammalian chromodomain proteins: their role in genome organisation and expression. Bioessays. 2000;22:124–127. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200002)22:2<124::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kellum R, Alberts B M. Heterochromatin protein 1 is required for correct chromosome segregation in Drosophila embryos. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:1419–1431. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly M, Burke J, Smith M, Klar A, Beach D. Four mating-type genes control sexual differentiation in the fission yeast. EMBO J. 1988;7:1537–1547. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klar A J, Bonaduce M J. swi6, a gene required for mating-type switching, prohibits meiotic recombination in the mat2-mat3 “cold spot” of fission yeast. Genetics. 1991;129:1033–1042. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klar A J, Ivanova A V, Dalgaard J Z, Bonaduce M J, Grewal S I. Multiple epigenetic events regulate mating-type switching of fission yeast. Novartis Found Symp. 1998;214:87–99. doi: 10.1002/9780470515501.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Douarin B, Nielsen A L, Garnier J M, Ichinose H, Jeanmougin F, Losson R, Chambon P. A possible involvement of TIF1α and TIF1β in the epigenetic control of transcription by nuclear receptors. EMBO J. 1996;15:6701–6715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehming N, LeSaux A, Schuller J, Ptashne M. Chromatin components as part of a putative transcriptional repressing complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7322–7326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S C, Palek J. Spectrin tetramer-dimer equilibrium and the stability of erythrocyte membrane skeletons. Nature. 1980;285:586–588. doi: 10.1038/285586a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorentz A, Ostermann K, Fleck O, Schmidt H. Switching gene swi6, involved in repression of silent mating-type loci in fission yeast, encodes a homologue of chromatin-associated proteins from Drosophila and mammals. Gene. 1994;143:139–143. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90619-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maundrell K. nmt1 of fission yeast. A highly transcribed gene completely repressed by thiamine. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10857–10864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maundrell K. Thiamine-repressible expression vectors pREP and pRIP for fission yeast. Gene. 1993;123:127–130. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90551-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Messmer S, Franke A, Paro R. Analysis of the functional role of the Polycomb chromo domain in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1241–1254. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moreno S, Klar A J S, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrow J S, Marchesi V T. Self-assembly of spectrin oligomers in vitro: a basis for a dynamic cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1981;88:463–468. doi: 10.1083/jcb.88.2.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Motzkus D, Singh P B, Hoyer-Fender S. M31, a murine homologue of Drosophila HP1, is concentrated in the XY body during spermatogenesis. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1999;86:83–88. doi: 10.1159/000015418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. A knowledge base for predicting protein localization sites in eukaryotic cells. Genomics. 1992;14:897–911. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nielsen A L, Ortiz J A, You J, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Khechumian R, Gansmuller A, Chambon P, Losson R. Interaction with members of the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family and histone deacetylation are differentially involved in transcriptional silencing by members of the TIF1 family. EMBO J. 1999;18:6385–6395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nimmo E R, Cranston G, Allshire R C. Telomere-associated chromosome breakage in fission yeast results in variegated expression of adjacent genes. EMBO J. 1994;13:3801–3811. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niwa O, Matsumoto T, Chikashige Y, Yanagida M. Characterization of Schizosaccharomyces pombe minichromosome deletion derivatives and a functional allocation of their centromere. EMBO J. 1989;8:3045–3052. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peterson K, Wang G Z, Horsley D, Richardson J C, Sapienza C, Latham K E, Singh P B. The M31 gene has a complex developmentally regulated expression profile and may encode alternative protein products that possess diverse subcellular localisation patterns. J Exp Zool. 1998;280:288–303. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19980301)280:4<288::aid-jez3>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Platero J S, Hartnett T, Eissenberg J C. Functional analysis of the chromo domain of HP1. EMBO J. 1995;14:3977–3986. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powers J A, Eissenberg J C. Overlapping domains of the heterochromatin-associated protein HP1 mediate nuclear localization and heterochromatin binding. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:291–299. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reuter G, Spierer P. Position-effect variegation and chromatin proteins. Bioessays. 1992;14:605–612. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robbins J, Dilworth S M, Laskey R A, Dingwall C. Two interdependent basic domains in nucleoplasmin nuclear targeting sequence: identification of a class of bipartite nuclear targeting sequence. Cell. 1991;64:615–623. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90245-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryan R F, Ayyanathan K, Schultz D C, Singh P B, Freidman J R, Fredericks W J, Rauscher F J. KAP-1 corepressor protein interacts and colocalizes with heterochromatic and euchromatic HP1 proteins: a potential role for Kruppel-associated box-zinc finger proteins in heterochromatin-mediated gene silencing. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4366–4378. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seeler J S, Marchio A, Sitterlin D, Transy C, Dejean A. Interaction of SP100 with HP1 proteins: a link between the promyelocytic leukemia-associated nuclear bodies and the chromatin compartment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7316–7321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sewalt R G A B, Gunster M J, van der Vlag J, Satijn D P E, Otte A P. C-terminal binding protein is a transcriptional repressor that interacts with a specific class of vertebrate polycomb proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:777–787. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaffer C D, Wallrath L L, Elgin S C R. Regulating genes by packaging domains: bits of heterochromatin in euchromatin? Trends Genet. 1993;9:35–37. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90171-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh P B, Miller J R, Pearce J, Kothary R, Burton R D, Paro R, James T C, Gaunt S J. A sequence motif found in a Drosophila heterochromatin protein is conserved in animals and plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:789–794. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smothers J F, Henikoff S. The HP1 chromo shadow domain binds a consensus peptide pentamer. Curr Biol. 2000;10:27–30. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)00260-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi K, Yamada H, Yanagida M. Fission yeast minichromosome loss mutants mis cause lethal aneuploidy and replication abnormality. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:1145–1158. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.10.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tartof K D, Bishop C, Jones M, Hobbs C A, Locke J. Towards an understanding of position-effect variegation. Dev Genet. 1989;10:162–176. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tartof K D, Bremer M. Mechanisms for the construction and developmental control of heterochromatin formation and imprinted chromatin domains. Development. 1990;1990(Suppl.):35–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thon G, Cohen A, Klar A J. Three additional linkage groups that repress transcription and meiotic recombination in the mating-type region of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1994;138:29–38. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thon G, Klar A J. The clr1 locus regulates the expression of the cryptic mating-type loci of fission yeast. Genetics. 1992;131:287–296. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wreggett K A, Hill F, James P S, Hutchings A, Butcher G W, Singh P B. A mammalian homologue of Drosophila heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) is a component of constitutive heterochromatin. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1994;66:99–103. doi: 10.1159/000133676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamada T, Fukuda R, Himeno M, Sugimoto K. Functional domain structure of human heterochromatin protein HP1Hsα: involvement of internal DNA-binding and C-terminal self-association domains in the formation of discrete dots in interphase nuclei. J Biochem. 1999;125:832–837. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ye Q, Worman H J. Interaction between an integral protein of the nuclear envelope inner membrane and human chromodomain proteins homologous to Drosophila HP1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14653–14656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ye Q A, Callebaut I, Pezhman A, Courvalin J C, Worman H J. Domain-specific interactions of human HP1-type chromodomain proteins and inner nuclear membrane protein LBR. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14983–14989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]