Abstract

The telomere of the silkworm Bombyx mori consists of (TTAGG/CCTAA)n repeats and harbors a large number of telomeric repeat-specific non-long terminal repeat retrotransposons, such as TRAS1 and SART1. To understand how these retrotransposons recognize and integrate into the telomeric repeat in a sequence-specific manner, we expressed the apurinic-apryrimidinic endonuclease-like endonuclease domain of TRAS1 (TRAS1 EN), which is supposed to digest the target DNA, and characterized its enzymatic properties. Purified TRAS1 EN could generate specific nicks on both strands of the telomeric repeat sequence between T and A of the (TTAGG)n strand (bottom strand) and between C and T of the (CCTAA)n strand (top strand). These sites are consistent with insertion sites expected from the genomic structure of boundary regions of TRAS1. Time course studies of nicking activities on both strands revealed that the cleavages on the bottom strand preceded those on the top strand, supporting the target-primed reverse transcription model. TRAS1 EN could cleave the telomeric repeats specifically even if it was flanked by longer tracts of nontelomeric sequence, indicating that the target site specificity of the TRAS1 element was mainly determined by its EN domain. Based on mutation analyses, TRAS1 EN recognizes less than 10 bp around the initial cleavage site (upstream 7 bp and downstream 3 bp), and the GTTAG sequence especially is essential for the cleavage reaction on the bottom strand (5′. . . TTAGGTT ↓ AGG . . . 3′). TRAS1 EN, the first identified endonuclease digesting telomeric repeats, may be used as a genetic tool to shorten the telomere in insects and some other organisms.

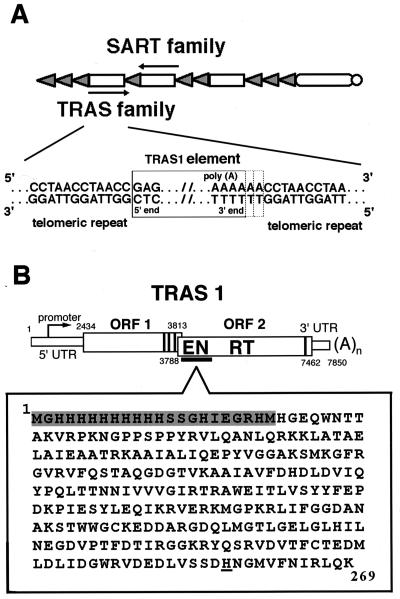

The extreme ends of the silkworm chromosome are composed of the simple telomeric repeat (TTAGG)n (26). When studying the telomeric structure of the silkworm, we found that more than 2,000 copies of non-long terminal repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposons have accumulated within the telomeric repeat (25). These Bombyx mori retrotransposons are sequence-specific elements that have been classified by differences in insertion sites and in amino acid sequences into two distinct, large families called TRAS (telomeric repeat-associated sequence) and SART (32). TRAS1 is the best-characterized family among the TRAS group (25). Most of the 250 copies of TRAS1 cluster at the telomeres of dozens of chromosomes and are highly conserved in structure without 5′-end truncation. The 5′ end of a 7.85-kb stretch of TRAS1 is precisely adjacent to CC of the (CCTAA)n telomeric strand ([CCTAA]n-CC-[5′ untranslated region (UTR)]). TRAS1 is transcribed in many tissues, and its transcription starts just after the 5′ end under the control of internal promoter in the 5′ UTR (31). These facts suggest that TRAS1 is an active retrotransposon. All TRAS1s analyzed so far terminate with oligo(A). We cannot define the exact junction site at the 3′ end because this oligo(A) sequence connects directly to CC of the (CCTAA) strand (Fig. 1A). Based on structural analysis of junction regions of TRAS1, it is also hard to identify target site duplication (TSD) of the telomere sequence, which is generated in the process of retrotransposition, because the target of TRAS1, the telomeric repeat (TTAGG/CCTAA) itself, is repetitious. To identify the exact junction site and TSD structure for TRAS1, the target specificity of TRAS1 must be studied by another functional assay.

FIG. 1.

Telomeric sequence-specific retrotransposons of the silkworm, B. mori. (A) Chromosome structure of B. mori. The shaded triangle indicates the telomeric repeat sequence 5′-(TTAGG)n/5′-(CCTAA)n. Open boxes indicate retrotransposons TRAS and SART, which are inserted into the telomeric repeat in opposite directions. Arrows show the directions of transcription by these elements. The 5′ and 3′ junction regions between TRAS1 and the telomeric repeat are shown below. The precise 3′ end of TRAS1 has not been determined. Dotted boxes indicate possible junction sites. (B) Structure of TRAS1. TRAS1 is inserted with its poly(A) tail facing toward the centromere. The ORFs of TRAS1 are depicted by open boxes, and the positions of a promoter, EN domain, and RT domain are indicated. The vertical lines near the C terminus of both ORFs represent the cysteine-histidine motifs. The amino acid sequence of TRAS1 EN expressed in E. coli is shown below. The N-terminal His tag sequence derived from pET16b is shaded. The putative active site (His-258) for endonuclease activity, which was changed to Ala in the mutant experiment, is underlined.

Non-LTR retrotransposons are a very abundant family and are found in most eukaryotes (11). Some of them are inserted within specific sites on the chromosome. Tx1 of Xenopus laevis inserts within another transposable element (13). CRE1, SLACS, and CZAR are found in the spliced leader exons of trypanosomes (1, 12, 34). R1 and R2 are located at specific sites of 28S rDNA in most insects (7, 10, 16). In two mosquito species, RT1 and RT2 are inserted at the same position about 630 bp downstream of the R1 insertion site (2, 27). Phylogenetic analysis showed that TRAS1 and SART1 are most similar to the insect 28S rDNA-specific retrotransposons R1 and RT1, respectively (21, 32). Presumably, the target specificity of these elements might have changed from rDNA to telomeric repeat or vice versa during insect evolution.

Recent reports have shown that two different types of endonuclease encoded in non-LTR retrotransposons function to define and cleave target site DNA. R2 and some other elements such as CRE1 and CZAR have a single open reading frame (ORF) that encodes an endonuclease domain near its C-terminal end. This type of endonuclease is similar in some residual motifs to various prokaryotic restriction endonucleases (38). The R2 protein first makes a specific nick on the noncoding bottom strand. Reverse transcription of the RNA template is then primed by the exposed 3′-hydroxyl group, a process termed target-primed reverse transcription (TPRT), before cleavage of the coding top strand (19). The second type of endonuclease is an apurinic-apyrimidnic endonuclease (APE)-like protein encoded in the N terminus of ORF2 of many non-LTR retrotransposon groups, such as L1, R1, Tx1L, and TRAS/SART elements, which have two ORFs. The APE-like domain of the human non-sequence-specific retroposon L1 preferentially cleaves the sequence similar to in vivo target sequences (6, 9). It has also been reported that R1 and Tx1L endonuclease specifically cleaves 28S rDNA and transposable element (Tx1D) sequence at the precise target site in vitro (5, 8), respectively.

To understand how TRAS1 recognizes and cuts the 5-bp repetitious telomeric repeats (TTAGG/CCTAA)n, we have expressed and purified the endonuclease (EN) domain of TRAS1 in Escherichia coli and characterized TRAS1 EN activities. Digestion patterns of end-labeled (TTAGG)n or (CCTAA)n by TRAS1 EN were clear 5-bp ladder signals, demonstrating that both telomeric strands were cleaved at specific sites. Various mutations on the substrate DNA also revealed that some sequences in the telomeric repeat are involved in the target-specific digestion by TRAS1 EN. This is the first evidence of a telomere-specific endonuclease. This endonuclease, which specifically digests and shortens the telomeric repeat, may thus be used as a genetic tool to study telomere function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of TRAS1 EN in the expression vector.

The TRAS1 EN domain was amplified by PCR with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) using primers s3788 (5′-AAAAAAAACATATGCACGGCGAGCAGTGGAA-3′) and a4528 (5′-AAAAAACTCGAGTTATTTTTGGAGTCTAATATTGAATACCATACC-3′) from the λB1 clone as a template (25). Each primer was designed to contain NdeI and XhoI sites, respectively (underlined in the primers above). The PCR product was digested with NdeI and XhoI and cloned into the NdeI and XhoI sites of the pET16b expression vector (Novagen), and the insert sequence of a candidate clone was confirmed. The cloned plasmid, named pHisT1EN, includes the first 741 bp, corresponding to the first 247 amino acids of ORF2, as shown in Fig. 1B, and the sequence encoding an MGHHHHHHHHHHSSGHIEGRHM tag on the N terminus of TRAS1 EN. This clone was designed to stop translation at the bases of TTA, which is a complement to the stop codon TAA (bold letters in the a4528 primer above).

A point mutation in the putative active site of EN (His→Ala at 258) was generated by a Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The primers used for constructing this mutant clone, named pHisT1EN (H258A), were s747 (5′-CGATGAAGACCTAGTGAGCTCGGATGCCAACGGTATGG-3′) and a784 (5′-CCATACCGTTGGCATCCGAGCTCACTAGGTCTTCATCG-3′).

Expression and purification of TRAS1 EN.

The pHisT1EN and pHisT1EN (H258A) DNAs were transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS (Novagen). A 50-ml culture of transformant was grown at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was then added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and incubation was continued for 8 h at 25°C. An accumulating protein was run on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and detected as a band with a calculated molecular mass of 30.3 kDa. We confirmed that this band corresponds to the target protein by Western blot analysis with anti-(His)6 antibody (Boehringer Mannheim). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and stored at −80°C. Purification processes followed the protocol of the His-Bind kit from Novagen (catalog number 70156). Freeze-thawed cell pellets were suspended in 6 ml of binding buffer (5 mM imidazol, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9]), and Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 0.1% and incubated for 10 min at 0°C. After the cell extracts were centrifuged at 39,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, the supernatants containing soluble proteins were filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane (Millipore) twice and applied to a Quick 900 Cartridge (Novagen). The cartridge was washed with 20 ml of binding buffer and subsequently with 10 ml of washing buffer (60 mM imidazol, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9]). Most of the target proteins were eluted with 2 ml of elution buffer (300 mM imidazol, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9]). The eluted proteins were ultrafiltered in storage buffer (500 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 20% glycerol, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) with an Ultrafree-MC centrifugal filter unit (Millipore). The concentrated proteins (about 2 ml) were stored at −80°C in 10-μl aliquots. The concentration of the eluted proteins was determined to be approximately 0.5 mg/ml by comparing the intensity of the band on a Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel with that of known amounts of bovine serum albumin (BSA) protein.

Assays for endonucleolytic activities.

To generate the substrates for TRAS1 EN, oligonucleotides (Nisshinbo) were end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Toyobo) and [γ-32P]ATP (ICN). In the assay for site specificity shown in Fig. 5, 60 bp of nontelomeric sequence was randomly selected from pBR322 sequence (accession number J01749, positions 81 to 140) (see Fig. 5C). The 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide was annealed with the nonlabeled complementary strand by incubation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by gradual cooling to room temperature. The samples were separated on 28% polyacrylamide gels, and the location of a precisely annealed oligonucleotide was detected by autoradiography. The band was cut out from the gel, incubated in elution buffer (500 mM ammonium acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% SDS) at 37°C for 4 h, and ethanol precipitated. The purified double-stranded oligonucleotides were dissolved in 0.5 ml of TE buffer (1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]) and stored at −30°C.

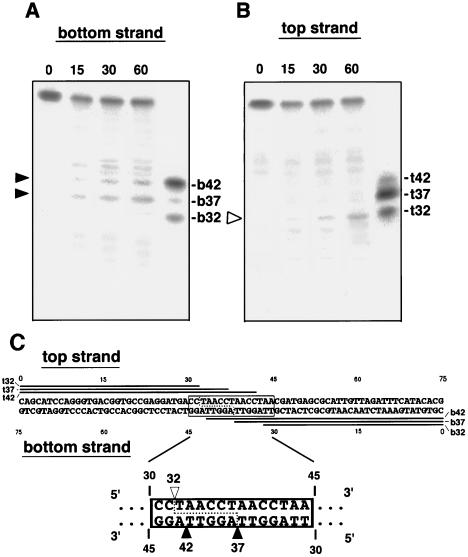

FIG. 5.

Target-specific cleavage of a long DNA substrate by TRAS1 EN. (A and B) A 75-bp-long DNA substrate contained a 15-bp telomere sequence (boxed region in C) flanked by nontelomeric sequences at both ends. The entire sequence of 75 bp is shown in panel C. The end-labeled 75-bp DNA was annealed with its complementary strand and cleaved with TRAS1 EN under the same conditions as in Fig. 2. Incubation time (in minutes) at 25°C is indicated on the top. Various lengths of end-labeled oligonucleotides (b32, b37, b42, t32, t37, and t42) were loaded as exact size markers as shown in panel C. (C) Schematic representation of the cleavage sites on both the top and bottom strands of the 75-bp substrate. Nucleotides are counted from the 5′ end of each strand. The solid arrowheads indicate cleavage sites on the bottom sequence. The open arrowhead marks the cleavage site on the top strand. A putative cleavage pattern on the double-stranded DNA is shown by a dotted line.

To determine the optimal conditions for assay of TRAS1 EN, we quantified the nicking activities for the (TTAGG)5 substrate by measuring the radioactivity of a specifically cleaved product at a 17-base position, (TTAGG)3-TT (see Results). Radiolabeled DNA substrate (1 ng) was cleaved most efficiently (approximately 13% of substrate DNA cleaved) with 0.2 μg of TRAS1 EN (data not shown). Optimum cleavage of substrates was observed at 25°C, and the reaction at 37°C showed a great decrease in activity (approximately 7% of the activity at 25°C). The reaction buffer for TRAS1 EN determined to show the highest endonucleolytic activity for oligonucleotide substrates contained 50 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)]-HCl (pH 6.0), 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and BSA (100 μg/ml). Substrate DNA was treated with purified TRAS1 EN protein in 10 μl of reaction buffer for 60 min at 25°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 50 mM. The reaction mixture was denatured in a loading buffer containing 75% formamide for 5 min at 95°C, immediately chilled on ice, and run on a 28% polyacrylamide denaturing sequencing gel. Quantitation of the reaction products was carried out with BAS 2500 imaging analyzer system (Fujifilm).

Various-sized oligonucleotides for telomeric repeat were end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP and used as precise molecular size markers: dG10 (5′-TTAGGTTAGG-3′), dG12 (5′-TTAGGTTAGGTT-3′), dG15 (5′-TTAGGTTAGGTTAGG-3′), dG17 (5′-TTAGGTTAGGTTAGGTT-3′), dC10 (5′-CCTAACCTAA-3′), dC12 (5′-CCTAACCTAACC-3′), dC15 (5′-CCTAACCTAACCTAA-3′), and dC17 (5′-CCTAACCTAACCTAACC-3′). The sequences of molecular size markers b42, b37, b32, t42, t37, and t32 are shown in Fig. 5.

RESULTS

TRAS1 EN has a specific nicking activity for telomeric repeats.

Sequence-specific retrotransposons generate a nick in the target DNA using their encoded endonucleases (5, 6, 8, 37). TRAS1 encodes an AP endonuclease-like domain, located upstream of the reverse transcriptase (RT) domain (Fig. 1B). Based on amino acid sequence alignment with other non-LTR retrotransposons, we have defined the EN domain of TRAS1 without excluding any of the proposed catalytic motifs (9) (Fig. 1B). TRAS1 EN was expressed in E. coli with an N-terminal (His)10 tag and purified by nickel chelation chromatography. A single band of the predicted size, 30.3 kDa, was observed in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A).

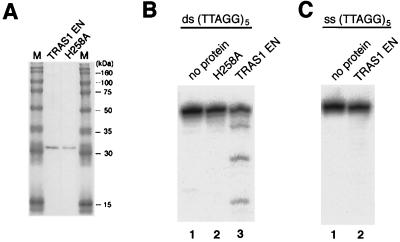

FIG. 2.

Expression and nicking activities of TRAS1 EN. (A) Purified TRAS1 EN and mutant protein H258A were separated on an SDS–8% PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie blue. Identical bands could be observed at 30.3 kDa. Lanes M, size markers. (B) Activity for double-stranded oligonucleotides. Telomeric G-strand (bottom strand) was end labeled and annealed to the complementary nonlabeled C-strands (top strand). Double-stranded (TTAGG)5 was treated with no protein (lane 1), 0.2 μg of H258A mutant protein (lane 2), and 0.2 μg of TRAS1 EN (lane 3) at 25°C for 60 min. The resulting fragments were separated on a 28% denaturing gel. (C) Activity for single-stranded oligonucleotides. Single-stranded (TTAGG)5 was prepared and incubated with no protein (lane 1) and with TRAS1 EN protein (lane 2). ds, double-stranded DNA; ss, single-stranded DNA.

To investigate the target site specificity of TRAS1 EN, we introduced a sensitive assay, using double-stranded oligonucleotide substrate: 5′-(TTAGG)n/5′-(CCTAA)n. The 5′ end of (TTAGG)n (G-strand) or (CCTAA)n (C-strand) was radiolabeled and annealed with the nonlabeled complementary oligonucleotide of the same length. In all experiments, only one strand of the double-stranded substrate was end labeled. The optimal conditions for endonucleolytic activity of the TRAS1 EN protein were determined for pH, salt concentration, and temperature (see Materials and Methods). When 0.2 μg of TRAS1 EN was added to the reaction mixture with end-labeled (TTAGG)5, ladder bands representing cleavage sites were clearly observed at intervals of 5 bp (Fig. 2B). Similar ladder patterns were also detected for various lengths of substrates (n = 6, 9, and 12; data not shown). These results demonstrate that TRAS1 EN cleaves the telomeric repeats at specific sites in vitro.

We have also expressed a mutated protein, H258A, which has a single-amino-acid substitution (His→Ala) (Fig. 1B) to test whether these nicking activities indeed result from TRAS1 EN itself. The histidine residue mutated in H258A is known to be essential for the catalysis of the L1 EN domain (9), exonuclease III (24), and DNase I (30). The H258A endonuclease could not make any nicks on the telomeric repeats (Fig. 2B), suggesting that other endonucleolytic activities from E. coli did not contaminate the purified protein. Therefore, we conclude that TRAS1 EN itself is responsible for the sequence-specific nicking activity on the TTAGG/CCTAA repeats.

Telomeres are known to have a longer G-strand than the complementary C-strand, creating the single-stranded 3′ overhanging structure at the end of the chromosome (15, 36). To exclude the possibility that TRAS1 EN associates with the telomeric G-strand overhang, we tested a single-stranded telomeric repeat as a substrate (Fig. 2C). We did not observe any ladder patterns for the 5′-end-labeled (TTAGG)5, indicating that TRAS1 EN has no nicking activity on the single-stranded telomeric repeats. To confirm that the missing activity on the single strand is not due to buffer conditions, we conducted another experiment as follows. After the TRAS1 EN reaction on the single-stranded substrate was complete, its complementary strand was readded and annealed. Under these conditions, we retried the cleavage reaction and observed 5-bp ladder bands (data not shown). This demonstrates that the absence of activity in the single-stranded reactions could be reconstituted by adding the complementary strand to the reaction. These results shown above strongly suggest that the target of TRAS1 EN in vivo is the telomeric region forming double-stranded DNA.

Determination of TRAS1 EN cleavage site of (TTAGG/CCTAA)n.

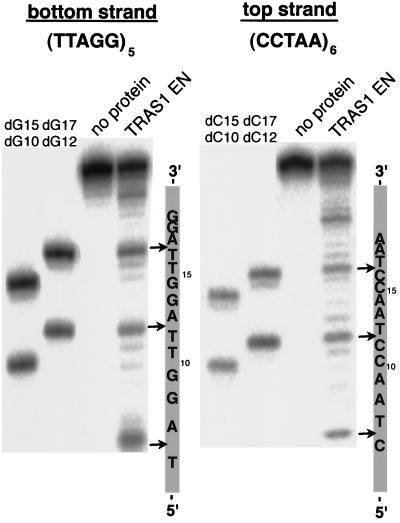

We next tried to determine the precise cleavage position of (TTAGG)n by comparing the sizes of the cleaved DNA products with those of the (TTAGG)n sequences of known sizes (Fig. 3A). The 5′-end-labeled bottom (TTAGG)n strand (G-strand) was cleaved by TRAS1 EN (as shown above) and run on PAGE alongside four DNA size markers [dG10, (TTAGG)2; dG12, (TTAGG)2TT; dG15, (TTAGG)3; and dG17, (TTAGG)3TT] that were end labeled with 32P at the 5′ ends. Major bands detected after digestion with TRAS1 EN were larger than the dG10 and dG15 markers by 2 bases and in identical positions to the dG12 and dG17 markers (Fig. 3, bottom strand). This suggests that all of the cleaved bottom strands terminate with the same structure of 5′-TTAGGTT in their 3′-end regions. Thus, we conclude that TRAS1 EN can cleave the TTAGG bottom strand specifically between T and A of the TTAGG repeats. When (TTAGG)5 was digested with TRAS1 EN, we observed major bands at 7, 12, 17, and 22 bp but not at 2 bp (data not shown). This suggests that only the 2-bp (TT) tract before the cleavage site is insufficient for TRAS1 EN endonucleolytic activity on the bottom strand. The upstream 7-bp sequence (TTAGGTT) and the downstream 3-bp sequence (AGG) from the cleavage site, however, are long enough to ensure the cleavage reaction.

FIG. 3.

Site-specific cleavage on both strands of telomeric repeats by TRAS1 EN. The 32P-end-labeled (TTAGG)5 (bottom strand) and (CCTAA)6 (top strand) were annealed with the complementary oligonucleotides. Reactions with TRAS1 EN were conducted as in Fig. 2 except that twice the amount of TRAS1 EN (0.4 μg) was added. Such an excess of TRAS1 EN caused nonspecific bands, which are useful for identifying the band positions (see text). Various lengths of 32P-labeled oligonucleotides (dG10, dG12, dG15, dG17, dC10, dC12, dC15, and dC17) were loaded as molecular standards (Materials and Methods). The major nicking sites by TRAS1 EN are shown by arrows on the right.

When the top (CCTAA) strand (C-strand) of the telomeric repeats was treated with TRAS1 EN, the 5-bp interval ladder pattern was also observed, indicating that the top strand was cleaved at the specific site in the repeat unit. Compared with four DNA size markers (dC10, dC12, dC15, and dC17), the top strand was specifically cleaved between C and T of (CCTAA)n (Fig. 3B). In the experiments shown in Fig. 3, twofold the optimal amount of TRAS1 EN (0.4 μg) was added. An excess amount of TRAS1 EN seemed to produce nonspecific bands, which were helpful for identifying 5-bp intervals of the main bands. It seemed that these nonspecific bands did not result from degradation of the specifically cleaved products with 3′-5′ exonuclease activity, since the kinetic study showed that all cleaved products were generated at the same rate (data not shown).

Previous studies showed that the 5′ end of TRAS starts between C and T of the CCTAA top strand (Fig. 1A) (25, 31). The specific cleavage between C and T of the top CCTAA strand in vitro shown here is consistent with the 5′ junction site of TRAS1 in the silkworm genome. We could not, however, define the exact TRAS1-(CCTAA) junction site at the 3′ end, since the oligo(A)-oligo(T) sequence connects directly to the telomeric (CCTAA/TTAGG)n sequence, proposing three possible 3′ junction structures: (TTAGG)n-TT-(T)n-(3′UTR), (TTAGG)n-T-(T)n-(3′UTR), and (TTAGG)n-(T)n-(3′UTR) (Fig. 1A). The result shown above indicates that TRAS1 cleaves its target sequence in the T-A junction on the (TTAGG)n bottom strand, suggesting that the 3′ junction structure between TRAS1 and the (TTAGG)n repeats in the genome is (TTAGG)n-TT↓(T)n.

TRAS1 EN cleaves the G-strand before the C-strand.

To determine whether TRAS1 EN has a strand preference for nicking, we examined the time course of TRAS1 EN endonucleolytic activities for the telomeric C-strand and G-strand. The double-stranded oligonucleotides, including only one end-labeled strand, were incubated with 0.2 μg of TRAS1 EN protein for 60 min. The changing patterns of 5-bp ladders during a 60-min reaction are shown in Fig. 4A and B. Cleaved products from the C-strand gradually increased over the course of 60 min. The cleavage reaction on the G-strand seemed to reach a maximum within the first 30 min, indicating that cleavage on the G-strand precedes that on the C-strand. To demonstrate this more clearly, the amounts of nicked substrates were quantified with the BAS2500 imaging analyzer and plotted against the reaction time (Fig. 4C). The G-strand was preferentially cleaved before the C-strand. Judging from the insertion structure of the TRAS1 element, the bottom and top strands correspond to the G- and C-strands, respectively. Interpretation of the TPRT model (19) suggests that cleavage on the bottom strand generates an exposed 3′-hydroxyl that serves as a primer for reverse transcription of the RNA template prior to the second-strand cleavage. Thus, cleavage of the G-strand before the C-strand is consistent with the proposed TPRT model.

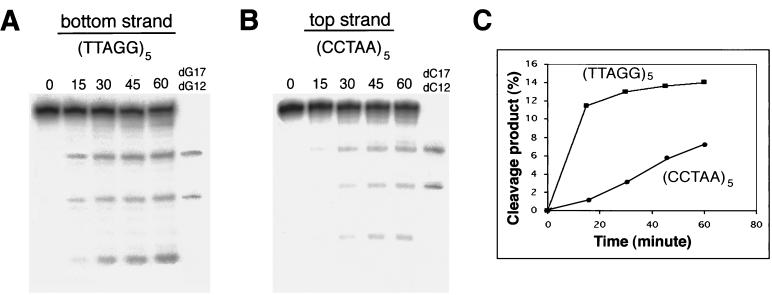

FIG. 4.

Kinetics of the cleavage reaction of TRAS1 EN. (A and B) Time course of nicking activities on the each strand of telomeres. TRAS1 EN (0.2 μg) was incubated with double-stranded substrates. Incubation time (in minutes) at 25°C is indicated on the top. Note that bottom-strand cleavage precedes top-strand cleavage. dG12, dG17, dC12, and dC17 were used as size markers. (C) Quantitation of the cleavage reactions shown in panels A and B. The 17-bp cleaved product (*5′-[TTAGG]3-TT↓-3′) in the bottom-strand reaction was quantified with the BAS system. Similarly, the 12-bp product (*5′-[CCTAA]2-CC↓-3′) in the top-strand reaction was measured. The percentage of nicked substrate was plotted against incubation time.

Target-specific cleavage of a long DNA substrate by TRAS1 EN.

All genomic copies of TRAS1 identified so far exist in the specific site of the telomeric repeat (25). To investigate whether this site specificity of TRAS1 for the telomere is defined by the EN domain itself, we assayed the nicking activities of TRAS1 EN for a long DNA substrate including both telomeric and nontelomeric sequences. The substrate contained three repeats of telomeric sequence (15 bp) flanked by 30 bp of nontelomeric sequences at both ends, which were randomly selected from pBR322 (Fig. 5C). Based on comparison of sizes of bands with several 32P-labeled oligonucleotides (b32, b37, b42, t32, t37, and t42), major bands were thought to be produced by specific cleavage within the telomeric sequence but not nontelomeric sequences. The TTAGG bottom strand was mainly cleaved between T and A of the telomeric unit at positions 37 and 42 from the 5′ end (shown as solid arrowheads) (Fig. 5A). The CCTAA top strand was cleaved between C and T at position 32 (open arrowhead in Fig. 5B). These cleaved products gradually increased during the 60-min reaction. It was also shown that the top-strand cleavage reaction occurred more slowly, compatible with the TPRT model. The observation that other probable target sites in the (TTAGG) unit (b32, t37, and t42) were not cleaved may reflect the loss of essential sequences recognized by TRAS1 EN around them (see below).

Several minor bands were observed in both bottom- and top-strand reactions. The nontelomeric sequence adjacent to the 3′ end of the telomeric repeat ([TTAGG]-46TCA48) is similar to TTA of the (TTAGG) unit and may cause the minor cleavages downstream of b42 in the bottom-strand reaction. The nonspecific bands in the middle of the gel in the top-strand reaction seemed to be due to incomplete denaturation of the oligonucleotides, because these bands were also observed before the reaction with TRAS1 EN (time zero). When we used another long substrate including (TTAGG)3 surrounded by 125 bp of nontelomeric sequences at both ends, TRAS1 EN cleaved DNA only within the telomeric repeats at the same cleavage patterns shown above (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that the EN domain of TRAS1 mainly determines the target specificity of TRAS1 elements for the telomere sequence.

Sequence involved in target site specificity by TRAS1 EN.

To investigate how TRAS1 EN protein recognizes a target site, we made several mutated substrates for the bottom strand and compared TRAS1 EN nicking activities for each substrate on PAGE. We first altered one nucleotide of the TTAGG unit to a cytosine (C) residue and made five different substrates (CTAGG)5, (TCAGG)5, (TTCGG)5, (TTACG)5, and (TTAGC)5 (mutated nucleotides are underlined) (Fig. 6). When the first two thymines of TTAGG were mutated, the nicking reaction of TRAS1 EN itself was not disturbed, although nonspecific bands could be observed. This suggests that the first and second T's of the TTAGG unit are important for cleavage site definition by TRAS1 EN. When three other substrates [(TTCGG)5, (TTACG)5, and (TTAGC)5] were used, the products cleaved by TRAS1 EN were greatly reduced, indicating that the third A and the fourth and fifth G's of the TTAGG unit are essential for the endonucleolytic activity of TRAS1 EN.

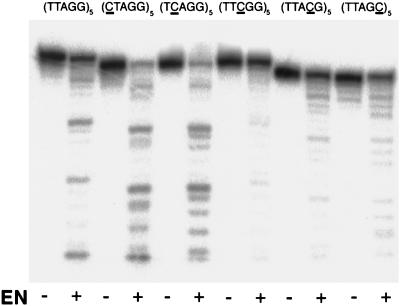

FIG. 6.

Endonucleolytic activities of TRAS1 EN for mutated telomeric repeats. Each nucleotide of the TTAGG unit of the bottom strand was changed individually to a cytosine residue. Treatment with TRAS1 EN protein was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Mutated nucleotides are underlined. EN: −, without TRAS1 EN; +, with TRAS1 EN.

The results in Fig. 6 indicate that all residues in the TTAGG unit are somehow involved in site-specific cleavage of the bottom strand by TRAS1 EN. In this assay, however, we cannot specify the nucleotide essential for TRAS1 EN activity in successive TTAGG sequences, since a nucleotide of TTAGG was altered in all repeating units. Hence, we made a series of mutated substrates for the (TTAGG)5 strand with a single base substitution and tried to figure out how TRAS1 EN recognizes the bases around the cleavage site. These mutated substrates contained substitutions to cytosine in the various positions flanking the cleavage site, from −7 to +8 (where 0 is cleavage site) (Fig. 7). We did not observe significant changes in the nicking activities for the substrates with mutations in positions +8 to +4 (Fig. 7) and in sites upstream of −8 (data not shown). When the 5′-flanking bases to the cleavage site in −7 to −3 were changed, the nicking activity of TRAS1 EN was reduced to about 40 to 80% of that for the nonmutated substrate (Cont., Fig. 7). Among them, the −3 mutated substrate had a severe effect on TRAS1 EN activity (38% of control). The nicking activity was also greatly inhibited by substitutions in the 3′-flanking sequence (+1 to +3), especially at +1 [(TTAGG)2TT↓CGG(TTAGG)2] and +2 [(TTAGG)2TT↓ACG(TTAGG)2] (20 and 25%, respectively). The results in Fig. 6 showing the great reduction in nicking activity for three substrates (TT↓CGG)n, (TT↓ACG)n, and (TT↓AGC)n support the above observation. In the case of (TT↓AGC)n, both the +3 and −3 positions from the cleavage sites were altered, which should have stronger blocking effects on nicking activity than a single substitution in either +3 or −3 in Fig. 7.

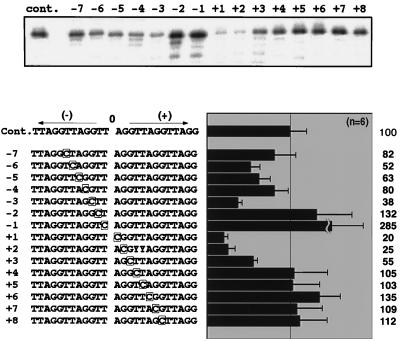

FIG. 7.

Definition of the bases involved in the cleavage reaction of TRAS1 EN. Treatment with TRAS1 EN protein was performed as described for Fig. 2. Each base from −7 to +8, where 0 is the cleavage site of the 12-bp cleaved product, in the 25-bp (TTAGG)5 bottom strand was systematically changed to a cytosine (boxed). The cleavage patterns around the 12-bp cleaved product in the gel are also shown. cont., control. The 12-bp band in each reaction was quantified, and its intensity relative to the control is shown on the right (control = 100). Each value represents the average, and error bars represent the standard error; both values were obtained from six independent experiments.

In contrast, the TRAS1 EN activity increased for the substrates mutated at −1 and −2 in appearance. Both substrates were, however, cleaved in many nonspecific sites upstream of the cleavage site (Fig. 7A), suggesting that the target site specificity of TRAS1 EN is relaxed by the −2 and −1 mutations. Combined with the aberrant cleavage patterns of (CT↓AGG)n and (TC↓AGG)n in Fig. 6, these results suggest that the TT sequence of TT↓AGG is involved in determining the precise cleavage site by TRAS1 EN.

In summary, mutations −7 to +3 to the cleavage site affect the cleavage reaction, especially the −3 to +2 bases (5′-. . . TTAGGTT↓AGGTT . . . -3′; underlined), and are essential for sequence-specific recognition and digestion on the bottom (TTAGG)n strand by TRAS1 EN.

DISCUSSION

TRAS1 EN recognizes and cleaves a specific DNA structure.

TRAS1 comprises two ORFs and encodes an AP endonuclease (APE)-like endonuclease at the N terminus of ORF2 (25). TRAS1 EN cleaves the bottom TTAGG strand between T and A at the boundary of the pyrimidine tract, TT, and the following purine tract, AGG. In the human L1 element, a similar target structure is observed in the first major nicking sites of the bottom strand (6, 9). The L1 endonuclease preferentially targets 5′(dTn-An) tracts and cleaves its T-A junction, illustrating that L1 and TRAS1 may have similar features for target site recognition in the bottom strand. Dinucleotide sequences such as TA, CA, and TG are known as specific DNA sites where kinks may occur under bending constraints (22). DNA kinks are defined as abrupt deflection of the double helical structure, leading to unstacking of two neighboring base pairs. It has been suggested that the EcoRV restriction enzyme (35) and the endonuclease of non-sequence-specific retrotransposons from plant and mammal cleave kinked DNA sites (17, 33). TRAS1 may also cleave the DNA kink at the T-A junction. Consistent with this, TRAS1 EN also cleaved a kinked C-A junction of the −1 mutant, 5′-(TTAGG)2-TCAGG-(TTAGG)2-3′, at a rate nearly threefold that of T-A cleavage in (TTAGG)5 (Fig. 7). On the top strand, in contrast, TRAS1 EN makes a specific nick between C and T of the CCTAA sequence. The C-T junction, which cannot form a kinked structure, may be cleaved by TRAS1 EN without recognizing these DNA structures.

The results shown in Fig. 3 suggest that two units of telomeric repeats, the 7 bp upstream and 3 bp downstream from the T-A junction (5′-TTAGGTT↓AGG-3′) are the minimum structures to ensure the endonucleolytic activity of TRAS1 EN. Consistent with this, single-base substitutions to cytosine upstream of −8 (data not shown) and downstream of +4 had little effect on the nicking activity of TRAS1 EN (Fig. 7). TRAS1 EN activity was greatly influenced by mutations in the −2 to +3 bases just adjacent to the cleavage site (5′- . . . TTAGGTT↓AGGTT . . . -3′; underlined). This suggests that the GTTAG pentamer may contain the first recognition region by TRAS1 EN on the bottom strand of the telomeric sequence. Such asymmetric recognition of the bases around the target site was also proposed for the endonuclease of R2 (37) and Tx1L (5).

Site-specific cleavage on the top strand by TRAS1 EN.

During retrotransposition by non-LTR-type retroelements, first-strand cleavage to prime reverse transcription of the RNA template was suggested to be followed by second-strand cleavage on the top strand. For site-specific integration, retrotransposons have to make a precise nick on the top strand. However, it is still ambiguous whether the APE-like (EN) encoded by site-specific retrotransposons is responsible for the second-strand cleavage reaction. Although R1 EN was shown to cleave its target 28s rDNA sequence in the precise site on the bottom strand, top-strand cleavage seemed to be less specific, with a few nonspecific products (8). Similarly, specific cleavage site on the top strand by Tx1L EN to ensure target site duplication has not yet been observed clearly (5). In this study, we first showed site-specific cleavage of the second strand by a site-specific non-LTR retrotransposon, TRAS1 (Fig. 5). The cleavage site between C and T of the (CCTAA)n top strand is consistent with insertion sites expected from the genomic structure of 5′ boundary regions of TRAS1 ([CCTAA]n-CC-[5′UTR of TRAS1]) (Fig. 1). Specific cleavage at the top strand by TRAS1 EN indicates that APE-like endonuclease could carry out the second-strand cleavage even in the absence of its own RNA template or reverse transcription reaction. This shows a striking contrast to a site-specific endonuclease encoded in the C-terminal region of the R2 element, which requires an RNA transcript for cleavage of the second DNA strand (20, 39).

How does TRAS1 EN accomplish a relatively high specificity for the top strand? R2Bm is able to cleave the top strand in a very specific manner. R2Bm protein is thought to accomplish these specific cleavages on both strands by remaining attached to the target DNA during the TPRT reaction (39). In contrast, it was suggested that Tx1L EN protein is released after cleaving the target DNA and that the full-length Tx1L sequences may be needed for the specific cleavage reaction on the top strand (5). Similar to Tx1L EN, TRAS1 EN seems to be capable of enzymatic turnover (data not shown), indicating that TRAS1 EN may carry out the second-strand cleavage without attachment to the target DNA. It is of interest that Tx1L EN and TRAS1 EN show different specificities for the top strands, though they may have similar enzymatic properties.

In host genomes, site-specific retrotransposons with APE-like endonuclease are usually flanked by TSD sequences at both ends. It is postulated that TSD is generated by cleavage patterns of APE-like endonuclease which cut the top strand at a site downstream of bottom-strand cleavage (4, 14). Although the TRAS1 element also encodes an APE-like endonuclease, its TSD sequence is unclear, because the target sequence of TRAS1 (i.e., the telomeric repeat) itself is repetitious. Figure 5B shows that the second cleavage of the top strand seemed to take place 6 bp upstream of the bottom-strand cleavage. This type of cleavage pattern by TRAS1 EN may generate 6-bp deletions at both ends instead of TSD, as suggested by former reports (4, 14).

Specific integration of TRAS1 into the telomere region.

If the TRAS1 element can integrate into its target site by recognizing only 10 bp (5′-TTAGGTTAGG-3′), as suggested above, TRAS1 should retrotranspose into many and various genomic locations that have the recognition sequence. The locations of TRAS1 were, however, restricted to the telomere region (25), indicating that integration of TRAS1 seems to be more specific to the telomeric repeat sequence in vivo.

Two models could explain the higher integration specificity of TRAS1 to telomeres in vivo. The first is that some other regions in TRAS1 might be required for recognizing the longer arrays of telomeric repeats or telomeres. In fact, TRAS1 EN structurally lacks the cysteine-histidine motifs which are located in the C terminus of ORF1 and ORF2 and supposed to be involved in DNA binding in R2 (38). Recently, we found a novel and putative myb-like DNA-binding structure between the EN and RT domains of ORF2 for the TRAS1 element (Y. Kubo and H. Fujiwara, submitted for publication). There is a possibility that some cysteine-histidine motifs or the myb-like domain may be involved in the observed higher specificity for telomeres.

The second model postulates that a TRAS1 integration complex interacts with a chromatin component specific for telomeres before the retrotransposition and then integrates by recognizing relatively short arrays of telomeric repeats. In the Saccharomyces cerevisiae LTR-type retrotransposon Ty5, which preferentially integrates into domains of silent chromatin at HM loci and telomeres, it has been proposed that target site specificity results from the recognition of specific chromatin components such as Sir3p and Sir4p (41).

As shown in Fig. 5, TRAS1 EN could make a specific nick on both strands of oligonucleotides even if it contained additional nontelomeric sequences. The EN domain of TRAS1 can cleave the target sequence in vitro. Therefore, we conclude that telomere-specific chromatin components or telomere-binding proteins may interact with TRAS1 protein first and then the EN domain of TRAS1 mainly defines the precise sequence for integration.

Application of TRAS1 EN for the telomere-nicking enzyme in vivo.

The data shown here suggest that TRAS1 has the potential to integrate into telomere sequences. These telomere-associated non-LTR retrotransposons may be involved in telomere maintenance, like HeT-A and TART in Drosophila telomeres (3, 18). On the other hand, this study raises the possibility that this telomere-specific endonuclease can be used as a negative regulator of telomeres. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence of a telomere-specific endonuclease. Recently, it was reported that human topoisomerase II cleaves tandem repeats of telomeric DNA, (TTAGGG)n, only in the presence of the topoisomerase II poison etoposide (40). This nicking activity, however, was not specific for the telomere sequence, since topoisomerase II itself is known to cleave a wide range of consensus sequences (29).

We suggest that TRAS1 EN cleaves TTAGG repeats interacting with the 5 bases of the GGTTA sequence, as shown in Fig. 7, indicating that this telomere-nicking enzyme may be applied to the study of other organisms which have a GGTTA sequence in their telomeric repeats, such as (TTAGG)n of insects (26, 28) and (TTAGGG)n of many species, including humans (23). To test this possibility, we tried to examine whether TRAS1 EN could cleave the human-type telomeric repeats (TTAGGG/CCCTAA)n. The results demonstrated that TRAS1 EN also nicked the TTAGGG bottom strand between T and A and that the cleaved products represented banding patterns with 6-bp but not 5-bp ladder signals (data not shown). Although further experiments will be necessary to clarify the specific digestion of other GGTTA-including telomeric repeats than (TTAGG)n by TRAS1 EN, this enzyme activity may be used in insects and other organisms to study telomere function in vitro and in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksoy S, Williams S, Chang S, Richards F F. SLACS retrotransposon from Trypanosoma brucei gambiense is similar to mammalian LINEs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:785–792. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besansky N J, Paskewitz S M, Hamm D M, Collins F H. Distinct families of site-specific retrotransposons occupy identical positions in the rRNA genes of Anopheles gambiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5102–5110. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.5102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biessmann H, Champion L E, O'Hair M, Ikenaga K, Kasravi B, Mason J M. Frequent transpositions of Drosophila melanogaster HeT-A transposable elements to receding chromosome ends. EMBO J. 1992;11:4459–4469. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke W D, Müller F, Eickbush T H. R4, a non-LTR retrotransposon specific to the large subunit rRNA genes of nematodes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4628–4634. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.22.4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen S, Pont-Kingdon G, Carroll D. Target specificity of the endonuclease from the Xenopus laevis non-long terminal repeat retrotransposon Tx1L. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1219–1226. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1219-1226.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cost G J, Boeke J D. Targeting of human retrotransposon integration is directed by the specificity of the L1 endonuclease for regions of unusual DNA structure. Biochemistry. 1998;37:18081–18093. doi: 10.1021/bi981858s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eickbush T H, Robins B. Bombyx mori 28S ribosomal genes contain insertion elements similar to the Type I and II elements of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1985;4:2281–2285. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Q, Schumann G, Boeke J D. Retrotransposon R1Bm endonuclease cleaves the target sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2083–2088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng Q, Moran J V, Kazazian H H, Jr, Boeke J D. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell. 1996;87:905–916. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81997-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujiwara H, Ogura T, Takada N, Miyajima N, Ishikawa H, Maekawa H. Introns and their flanking sequences of Bombyx mori rDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:6861–6869. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.17.6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabriel A, Boeke J D. Retrotransposon reverse transcription. In: Skalka A M, Goff S P, editors. Reverse transcriptase. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 275–328. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabriel A, Yen T J, Schwartz D C, Smith C L, Boeke J D, Sollner-Webb B, Cleveland D W. A rapidly rearranging retrotransposon within the miniexon gene locus of Crithidia fasciculata. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:615–624. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett J E, Knutzon D S, Carroll D. Composite transposable elements in the Xenopus laevis genome. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3018–3027. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George J A, Burke W D, Eickbush T H. Analysis of the 5′ junctions of R2 insertions with the 28S gene: implications for non-LTR retrotransposition. Genetics. 1996;142:853–863. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson E. Telomere structure. In: Blackburn E H, Greider C W, editors. Telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakubczak J L, Burke W D, Eickbush T H. Retrotransposable elements R1 and R2 interrupt the rRNA genes of most insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3295–3299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jurka J, Klonowski P, Trifonov E N. Mammalian retroposons integrate at kinkable DNA sites. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1998;15:717–721. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1998.10508987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levis R W, Ganesan R, Houtchens K, Tolar L A, Sheen F M. Transposons in place of telomeric repeats at a Drosophila telomere. Cell. 1993;75:1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90318-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luan D D, Korman M H, Jakubczak J L, Eickbush T H. Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell. 1993;72:595–605. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luan D D, Eickbush T H. Downstream 28S gene sequences on the RNA template affect the choice of primer and the accuracy of initiation by the R2 reverse transcriptase. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4726–4734. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik H S, Burke W D, Eickbush T H. The age and evolution of non-LTR retrotransposable elements. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:793–805. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNamara P T, Bolshoy A, Trifonov E N, Harrington R E. Sequence-dependent kinks induced in curved DNA. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1990;8:529–538. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1990.10507827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyne J, Ratliff R L, Moyzis R K. Conservation of the human telomere sequence (TTAGGG)n among vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7049–7053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mol C D, Kuo C F, Thayer M M, Cunningham R P, Tainer J A. Structure and function of the multifunctional DNA-repair enzyme exonuclease III. Nature. 1995;23:381–386. doi: 10.1038/374381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okazaki S, Ishikawa H, Fujiwara H. Structural analysis of TRAS1, a novel family of telomeric repeat-associated retrotransposons in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4545–4552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okazaki S, Tsuchida K, Maekawa H, Ishikawa H, Fujiwara H. Identification of a pentanucleotide telomeric sequence, (TTAGG)n, in the silkworm Bombyx mori and in other insects. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1424–1432. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paskewitz S M, Collins F H. Site-specific ribosomal DNA insertion elements in Anopheles gambiae and A. arabiensis: nucleotide sequence of gene-element boundaries. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8125–8133. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.20.8125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahara K, Marec F, Traut W. TTAGG telomeric repeats in chromosomes of some insects and other arthropods. Chromosome Res. 1999;7:449–460. doi: 10.1023/a:1009297729547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzner J R, Chung I K, Gootz T D, McGuirk P R, Muller M T. Analysis of eukaryotic topoisomerase II cleavage sites in the presence of the quinolone CP-115,953 reveals drug-dependent and -independent recognition elements. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:238–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suck D, Lahm A, Oefner C. Structure refined to 2Å of a nicked DNA octanucleotide complex with DNase I. Nature. 1988;332:464–468. doi: 10.1038/332464a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi H, Fujiwara H. Transcription analysis of the telomeric repeat-specific retrotransposons TRAS1 and SART1 of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2015–2021. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.9.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi H, Okazaki S, Fujiwara H. A new family of site-specific retrotransposons, SART1, is inserted into telomeric repeats of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1578–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.8.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tatout C, Lavie L, Deragon J M. Similar target site selection occurs in integration of plant and mammalian retroposons. J Mol Evol. 1998;47:463–470. doi: 10.1007/pl00006403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villanueva M S, Williams S P, Beard C B, Richards F F, Aksoy S. A new member of a family of site-specific retrotransposons is present in the spliced leader RNA genes of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:6139–6148. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.6139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkler F K, Banner D W, Oefner C, Tsernoglou D, Brown R S, Heathman S P, Bryan R K, Martin P D, Petratos K, Wilson K S. The crystal structure of EcoRV endonuclease and of its complexes with cognate and non-cognate DNA fragments. EMBO J. 1993;12:1781–1795. doi: 10.2210/pdb4rve/pdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright W E, Tesmer V M, Huffman K E, Levene S D, Shay J W. Normal human chromosomes have long G-rich telomeric overhangs at one end. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2801–2809. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong Y E, Eickbush T H. Functional expression of a sequence-specific endonuclease encoded by the retrotransposon R2Bm. Cell. 1988;55:235–246. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J, Malik H S, Eickbush T H. Identification of the endonuclease domain encoded by R2 and other site-specific, non-long terminal repeat retrotransposable elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7847–7852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Eickbush T H. RNA-induced changes in the activity of the endonuclease encoded by the R2 retrotransposable element. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3455–3465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon H J, Choi I Y, Kang M R, Kim S S, Muller M T, Spitzner J R, Chung I K. DNA topoisomerase II cleavage of telomeres in vitro and in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1395:110–120. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu Y, Zou S, Wright D A, Voytas D F. Tagging chromatin with retrotransposons: target specificity of the Saccharomyces Ty5 retrotransposon changes with the chromosomal localization of Sir3p and Sir4p. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2738–2749. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]