Abstract

Although most cells are capable of transporting polyamines, the mechanism that regulates polyamine transport in eukaryotes is still largely unknown. Using a genetic screen for clones capable of restoring spermine sensitivity to spermine-tolerant mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we have demonstrated that Sky1p, a recently identified SR protein kinase, is a key regulator of polyamine transport. Yeast cells deleted for SKY1 developed tolerance to toxic levels of spermine, while overexpression of Sky1p in wild-type cells increased their sensitivity to spermine. Expression of the wild-type Sky1p but not of a catalytically inactive mutant restored sensitivity to spermine. SKY1 disruption results in dramatically reduced uptake of spermine, spermidine, and putrescine. In addition to spermine tolerance, sky1Δ cells exhibit increased tolerance to lithium and sodium ions but somewhat increased sensitivity to osmotic shock. The observed halotolerance suggests potential regulatory interaction between the transport of polyamines and inorganic ions, as suggested in the case of the Ptk2p, a recently described regulator of polyamine transport. We demonstrate that these two kinases act in two different signaling pathways. While deletion or overexpression of SKY1 did not significantly affect Pma1p activity, the ability of overexpressed Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p to increase sensitivity to LiCl depends on the integrity of PPZ1 but not of ENA1.

The polyamines spermine and spermidine and their precursor putrescine are ubiquitous polycations demonstrated to be essential for various cellular functions such as growth and proliferation, differentiation, transformation, and apoptosis (39, 40, 51, 52, 56). The intracellular concentration of polyamines is tightly regulated at many control levels (6, 40, 51). Although cells contain highly orchestrated groups of enzymes that modulate the intracellular concentration of polyamines by controlling their synthesis and degradation, most cells also have the capacity to take up polyamines from their environment (17, 41, 47). Drugs interfering with polyamine biosynthesis were demonstrated to have considerable potential for use as therapeutic agents (29, 40, 42). Clearly, protocols minimizing uptake of exogenous polyamines via the polyamine transport system will be needed in order to reveal the entire potential of such inhibitors. Conversely, protocols increasing selective polyamine uptake will facilitate the use of polyamine analogues which have potent antiproliferative activity and therefore are promising agents for the treatment of cancer (3, 31, 32).

Polyamine uptake has been characterized in great detail in bacteria. Escherichia coli contains three different polyamine transport pathways (for a review, see reference 16 and references therein). Two are ABC (ATP-binding cassette) transporters; one is specific for putrescine (PotF-I), while the second displays a preference for spermidine (PotA-D). Both transporters consist of a substrate-binding protein, two channel-forming proteins, and a membrane-associated ATPase. The third transport system (PotE) is putrescine specific, mediating both uptake and excretion.

Although mammalian cells lacking polyamine transport activity have been available for quite a while (14, 28), they did not enable isolation and cloning of the polyamine transporters or regulators of the polyamine transport process (2). The only mammalian gene implicated presently in the regulation of polyamine transport is antizyme, a regulator of ornithine decarboxylase degradation (35, 36) that was also implicated in negative regulation of polyamine uptake via an as yet unknown mechanism (33, 46, 50).

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a vacuolar membrane transporter (Tpo1p) and two protein kinases (Ptk1p and Ptk2p) that regulate plasma membrane polyamine transport have been identified. Tpo1p, which excretes spermidine, was identified based on its homology to the Bacillus subtilis Blt, a multidrug transporter (53). The Ptk1p and Ptk2p kinases, which stimulate polyamine uptake, were identified by genetic screens (20, 21, 38). These two kinases belong to a subfamily that is unique to S. cerevisiae and regulates plasma membrane transporters (15). This subfamily also includes the Hal4 and Hal5 protein kinases that regulate ion homeostasis by activating the potassium transporters Trk1 and Trk2 (34). Another member of this family of kinases is Npr1, which is required for the derepression of several nitrogen permeases in low-nitrogen-containing media (54) and was recently demonstrated to activate spermidine uptake in NH4+-rich medium (22).

Sky1p is a recently identified SR protein kinase (SRPK) of the budding yeast that, similar to its metazoan counterparts, may function in mRNA maturation by regulating splicing or transport of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (49). Here we demonstrate that Sky1 is also a key regulator of polyamine transport. Interestingly, similar to the recently identified Ptk2p, Sky1p is also involved in regulating ion homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

The S. cerevisiae strains used in the present work are listed in Table 1. These strains were routinely maintained in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% d-glucose) or in Mg2+-limited synthetic complete (MLSC) medium supplemented with 50 μM MgSO4 as described (30) and with the required essential amino acids. Yeast cells were transformed by the lithium acetate method (18).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SP1 | MATa ade8 leu2 ura3 trp1 his3 lys2 | J. Gerst |

| W303-1B | MATα ade2 leu2 ura3 trp1 his3 lys2 | J. Gerst |

| BY4742 | MATα leu2 ura3 his3 lys2 | EUROSCARF |

| sky1Δ | BY4742 with YMR216C::kanMX4 | Research Genetics |

| YMR215WΔ | BY4742 with YMR215W::kanMX4 | Research Genetics |

| YMR214WΔ | BY4742 with YMR214W::kanMX4 | Research Genetics |

| ptk1Δ | BY4742 with YKL198C::kanMX4 | Research Genetics |

| ptk2Δ | BY4742 with YJR059W::URA3 | This study |

| sky1Δ ptk2Δ | sky1Δ with YJR059W::URA3 | This study |

| ptk1Δ ptk2Δ | ptk1Δ with YJR059W::URA3 | This study |

| npl3Δ | BY4742 with YDR432W::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| gbp2Δ | BY4742 with YCL011C::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| mud2Δ | BY4742 with YKL074C::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| ppz1Δ | BY4742 with YML016C::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| ppz2Δ | BY4742 with YDR436W::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| cnb1Δ | BY4742 with YKL190W::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| cnb1 Δppz1Δ | cnb1Δ with YML016C::URA3 | This study |

| G19 | MATα leu2 ena1::HIS3::ena4 | A. Rodriguez-Navarro |

Isolation of spermine transport-deficient mutants.

The selection method employed in the present study is based on the sensitivity of yeast cells to spermine, as demonstrated previously (20). Briefly, the haploid strains SP1 (MATa) and W303-1b (MATα) were mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate (0.03%, vol/vol) (44). The cells were then plated on YPD agar plates containing 1.5 mM spermine to select resistant clones. Diploids were generated between the tested mutants and the wild-type strain of the opposite mating type (SP1 or W303-1b) in order to determine whether the phenotype of the resulting mutants is recessive or dominant. Complementation groups were determined by crossing SP1-born and W303-1b-born mutants and testing their growth on MLSC agar plates containing 1.5 mM spermine. MLSC agar plates were used to reduce the inhibitory effect of Mg2+ on the uptake of spermine (20).

Isolation of the SKY1 gene.

Spermine transport mutant cells of the C complementation group (sptC) were transformed with a yeast genomic DNA library constructed in the single-copy-number plasmid YCP50. The transformed cells were plated on SC-Leu plates, and the resulting colonies were replica plated on MLSC-Leu plates containing or lacking 1.5 mM spermine. The plasmid was rescued from clones that regained sensitivity to 1.5 mM spermine and tested in a second round of transformation. The 5′ and 3′ ends of the cloned inserts were sequenced in order to determine their positions in the yeast genome.

Plasmids and gene disruption.

The DNA segments containing the SKY1, PTK1, PTK2, and PPZ1 genes were cloned from genomic DNA by PCR and ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Following sequencing, these fragments were transferred into the SalI site of the yeast high-copy-number expression vector pAD54, placing them in frame downstream from a hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged segment. The primers used for the PCR are as follows: SKY1, 5′-TGTCGACAATTAACTATCCTGGGTTT-3′ and 5′-AGTCGACTCAATGTCTTTTATGATCGC-3′; PTK1, 5′-GTCGACAGTCTCACACAATCATT-3′ and 5′-GTCGACGACGCTAAAACCGTG-3′; PTK2, 5′-GTCGACGGCGGGAAACGGTAAG-3′ and 5′-GTCGACGTCTATCTTGAGATAAAG-3′; and PPZ1, 5′-AATGTCGACTTCAAGTTCAAAATCTTCG-3′ and 5′-AAGTCGACGTAAATTAACTGTTGAGATTCG-3′. In order to disrupt the PTK2 gene, the corresponding DNA was digested with AvaI and ClaI, and the released fragment was replaced by an AvaI-BamHI-ClaI adapter. Then a 1.1-kb BamHI fragment encompassing the URA3 gene was cloned into the implanted BamHI site. The resulting PTK2::URA3 fragment was transfected into wild-type BY4742, sky1Δ, or ptk1Δ cells. URA3-positive colonies were selected, and the disruption of the PTK2 gene was checked by PCR. In order to disrupt the PPZ1 gene, the 1.1-kb BamHI URA3 fragment was cloned between the two BglII sites of PPZ1. The resulting PPZ1::URA3 fragment was transfected into cnbΔ cells.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

The ATP-binding site SKY1 mutant, K187A, was generated by the uracil incorporation method of site-directed mutagenesis (24). The primer used was 5′-CCGAACAATCGCCATAGCAAC-3′, containing an alteration of lysine 187 to alanine.

Growth assays.

The growth of yeast strains on YPD or MLSC-Leu plates containing different additives was performed by spotting 2 μl from fivefold dilutions of cultures at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1, or by streaking cells on the plates. In order to measure growth in liquid medium, exponentially growing cultures were diluted in YPD medium containing different additives at the indicated concentrations. Growth was determined by measuring cell density at OD600 at different times thereafter.

Polyamine uptake analysis.

Cells were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase (OD600 = 1.1 to 1.3), washed three times in glucose-citrate buffer (50 mM sodium citrate [pH 5.5], 2% d-glucose), and resuspended in the same buffer at a concentration of 108 cells/ml. Transport was initiated by adding 0.2 volume of [14C]putrescine (10 Ci/mol at 50 μM), [3H]spermidine (50 Ci/mol at 100 μM) (both from Dupont-NEN), or [14C]spermine (10 Ci/mol at 100 μM) (from Amersham Pharmacia), and the cells were incubated at 30°C with mild shaking. Uptake was stopped by transferring 100-μl aliquots (in duplicate) into 1 ml of ice-cold stop buffer (glucose-citrate buffer containing 2 mM putrescine, spermidine, or spermine). The cells were then layered on cellulose-acetate filters (0.45-μm pore size) that had been washed with stop buffer. The filters were washed three times with stop buffer, and the retained radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

Western blot analysis.

Cells from 1 ml of culture were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 μl of sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 20% glycerol, 1.4 M β-mercaptoethanol bromophenol blue). Following 5 min of boiling, 5-μl aliquots were fractionated by SDS–8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were probed with anti-HA monoclonal antibody (BabCo) and goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase conjugate as a secondary antibody. Signals were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce).

Membrane preparation and ATPase activity determination.

Total membrane fractions were prepared essentially as described (55). Briefly, log-phase cells from 100 ml of culture were pelleted, washed, and resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 0.3 M sorbitol, 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitors; in some experiments sorbitol was replaced with 250 mM glucose). Cells were then lysed at 4°C using glass beads, and the lysate was centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min to remove unbroken cells. Membranes were then pelleted at 4°C by centrifugation for 1 h at 100,000 × g. The membranes were washed twice and stored at −80°C in storage buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol). Vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity was measured in the presence or absence of 100 mM sodium orthovanadate. Equal amounts of proteins from the membrane fractions were added to the assay mixture containing 10 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-Tris (pH 6.5), 5 mM disodium ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM NaN3, 5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, and 25 μg of pyruvate kinase. The reaction was carried out for 10 to 30 min at 30°C. Free phosphate was determined according to the Fiske-Subbarow procedure (9). Activity is expressed as arbitrary units based on absorption at 820 nm.

Sequence analysis.

SKY1 genomic DNA was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from sptC and wild-type cells and using the oligonucleotides 5′-GAGGTTGAAGAGATAGAGTAAAG and 5′-TCAATGTCTTTTATGATCGCGG as 5′ and 3′ primers, respectively. The resulting DNA was purified using the Qiagen Qiaquick PCR purification kit. The purified fragment was subjected to automated sequencing using primers scattered along the DNA.

RNA analysis.

Yeast cells from 50-ml cultures were harvested by centrifugation, and RNA was prepared by phenol extraction with glass beads (19). Formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis and blot hybridization were performed using a Gene-screen-plus membrane (NEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Yeast serine/threonine kinase Sky1 is involved in regulating spermine transport.

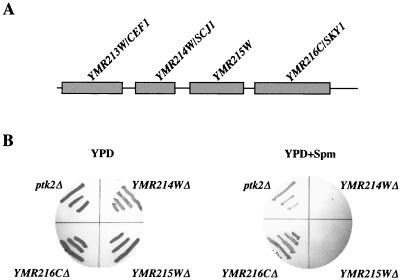

We have utilized a previously described selection scheme for the isolation of spermine-tolerant yeast mutant cells (20, 38). Cells of the haploid strains SP1 (MATa) and W303-1b (MATα) were subjected to ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis and plated on YPD plates containing 1.5 mM spermine. Sixty spermine-tolerant (spt) mutants of each strain were tested for carrying a dominant or recessive mutation by crossing them with wild-type cells of the other strain and testing the ability of the resulting diploids to grow in the presence of 1.5 mM spermine. All the mutants were demonstrated to carry a recessive mutation. Next, by crossing mutants from one strain to mutants of the other strain, we have so far identified seven independent complementation groups (sptA to sptG). A single-copy-number vector (YCP50) carrying a yeast genomic library was then transfected into the mutant cells, and the transformants were plated as duplicates on MLSC-Leu plates either containing or lacking 1.5 mM spermine. Colonies that failed to grow on plates containing 1.5 mM spermine were identified, and the plasmids within them were rescued. Several plasmids have been isolated so far by screening three of the mutants (sptA to sptC) which, upon retransformation, restored sensitivity to spermine. One of these plasmids, which was rescued from the sptA mutant, harbors a genomic segment encoding several open reading frames (ORFs), among them the previously described PTK2, encoding a serine/threonine kinase shown to be involved in regulating polyamine transport (21, 38). The other plasmids isolated from both the sptB and sptC mutants harbor a genomic insert containing several ORFs which were not previously implicated in polyamine transport. One of these plasmids (rescued from the sptC mutant) contains a genomic segment from chromosome 13, encompassing four ORFs (Fig. 1A). These ORFs encode a component of a protein complex associated with the splicing factor Prp19p (CEF1), a dnaJ homolog (SCJ1), a hypothetical ORF (YMR215W), and a serine protein kinase (SKY1). In order to determine which of these ORFs is involved in regaining spermine sensitivity, we obtained strains containing deletions of three of these ORFs. Deletion of the fourth ORF (CEF1) was not tested because of its haploid lethality. Cells containing deletions of these three ORFs as well as Ptk2Δ cells (serving as a positive control) were tested for growth in the presence of 1.5 mM spermine. As demonstrated in Fig. 1B, of the tested strains, only sky1Δ cells grow efficiently on the spermine-containing plates.

FIG. 1.

Isolation and demonstration of the involvement of SKY1 in spermine tolerance. (A) Structure of the genomic clone selected for restoring spermine sensitivity to the spermine-tolerant sptC mutant. The four ORFs are shown as boxes and their names are indicated. (B) Deletion of SKY1 confers spermine tolerance. Yeast strains containing a disruption of three of the four indicated ORFs were tested for spermine tolerance by streaking on YPD agar plates containing 1.5 mM spermine (Spm). ptk2Δ cells, which were previously demonstrated to confer spermine tolerance, served as a positive control.

The Sky1 protein was recently identified as an SRPK of the budding yeast (47). Sky1p may function similarly to its metazoan counterparts in mRNA maturation by regulating splicing or transport of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (49). The SRPKs phosphorylate serine residues within serine/arginine-rich domains of members of the SR family of splicing factors. Sky1 appears to be the only SRPK in budding yeast (49).

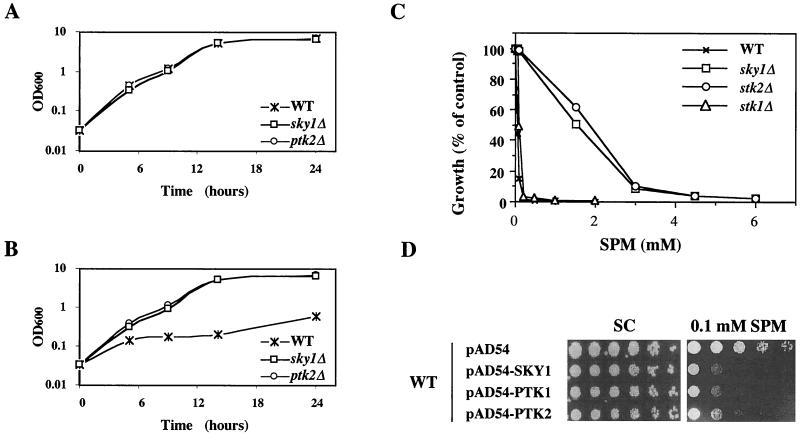

In order to make a quantitative assessment of the role of Sky1p in regulating tolerance to spermine, we characterized the growth of sky1Δ cells in the presence of various concentrations of spermine. Under standard conditions in nutrient-rich medium, the growth rate of the sky1Δ mutant cells was indistinguishable from that of wild-type cells (Fig. 2A), indicating that SKY1 disruption does not affect cell viability or growth in nutrient-rich medium. In the presence of 1.5 mM spermine, the growth of wild-type cells was strongly inhibited, while the growth of sky1Δ cells was practically unaffected (Fig. 2B). The growth of sky1Δ cells was indistinguishable from that of ptk2Δ cells (Fig. 2B). sky1Δ and ptk2Δ cells also demonstrated similar tolerance to increasing spermine concentrations (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the growth of ptk1Δ cells was inhibited by spermine to the same extent as that of wild-type cells. Overexpression of all three kinases in wild-type cells significantly increased their sensitivity to spermine (Fig. 2D). Forced expression of wild-type Sky1p but not of a catalytically inactive mutant of it (the ATP-binding site mutant Sky1p K187A (57) restored sensitivity to spermine in sky1Δ and sptC cells (Fig. 3), demonstrating that the kinase activity of Sky1p is essential for mediating spermine sensitivity.

FIG. 2.

Effect of SKY1 disruption and Sky1p overexpression on growth tolerance to spermine. (A) Basal growth rate of wild-type (WT), sky1Δ, and ptk2Δ cells. (B) Effect of 1.5 mM spermine on the growth of wild-type, sky1Δ, and ptk2Δ cells. (C) Effect of spermine concentration on the growth of wild-type, sky1Δ, ptk1Δ, and ptk2Δ cells as determined after 16 h of incubation. (D) Sky1p as well as Ptk1p and Ptk2p were overexpressed in wild-type cells from the pAD54 expression vector. Fivefold dilutions of the resulting transformants were spotted on MLSC plates with and without 0.1 mM spermine (SPM).

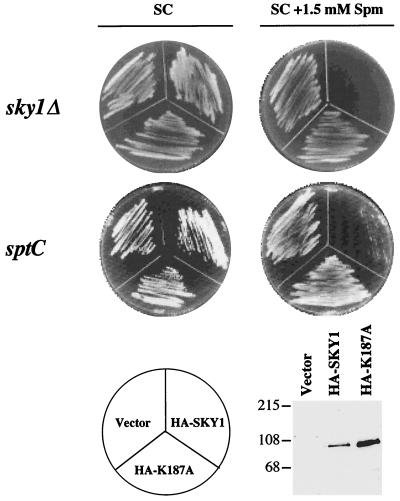

FIG. 3.

Kinase activity of Sky1p is required for reversing the spermine-tolerant phenotype of sky1Δ cells. The growth of sky1Δ cells and of the sptC cells that were transformed with empty vector (pAD54) or with constructs encoding wild-type SKY1 or its catalytically inactive variant K187A (both with an amino-terminal HA tag) was determined on solid MLSC plates containing 1.5 mM spermine (Spm). The expression of wild-type Sky1 protein and of the catalytically inactive K187A mutant protein was determined by Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibodies as described in the text. Sizes are shown in kilodaltons.

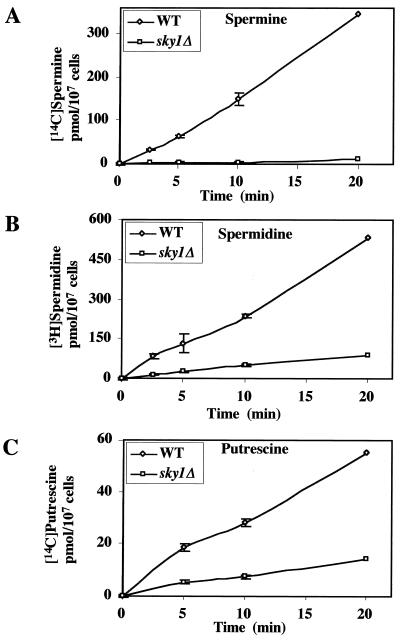

SKY1 disruption inhibits polyamine transport.

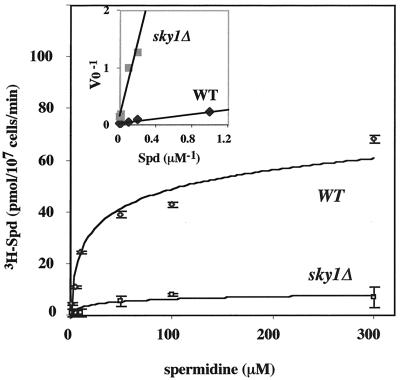

Next we set out to determine whether the resistance of sky1Δ cells to toxic levels of spermine is caused by their reduced ability to take up polyamines. For this purpose, we directly measured uptake of polyamines by sky1Δ and wild-type cells. Deletion of SKY1 almost completely eliminated the accumulation of spermine in the cells (Fig. 4A) and severely inhibited the accumulation of spermidine and putrescine (Fig. 4B and C, respectively). Kinetic analysis demonstrated that the disruption of SKY1 reduced Vmax by fivefold (7.83 pmol/min per 107 cells for sky1Δ cells compared to 40.5 pmol for wild-type cells) and decreased the affinity towards spermidine (Km = 48.5 μM for sky1Δ cells versus 8.18 μM for wild-type cells) (Fig. 5). We therefore conclude that the Sky1 protein kinase is involved in regulating polyamine transport.

FIG. 4.

Effect of SKY1 disruption on the time course of putrescine, spermidine, and spermine uptake. The uptake of [14C]spermine, [3H]spermidine (both at 20 μM), and [14C]putrescine (10 μM) by wild-type (WT) and sky1Δ cells was determined at the indicated times as described in Materials and Methods. The results presented are averages of three determinations ± standard deviation.

FIG. 5.

Initial velocity of [3H]spermidine uptake in wild-type (WT) and sky1Δ cells. The uptake of [3H]spermidine (Spd) at the indicated concentrations was determined after 1.5 min of incubation as described in Materials and Methods. The results presented are averages of three determinations ± standard deviation. The insert presents a double reciprocal plot of the initial rate of [3H]spermidine uptake in wild-type and sky1Δ cells.

Disruption of SKY1 leads to salt tolerance but increases sensitivity to osmotic shock.

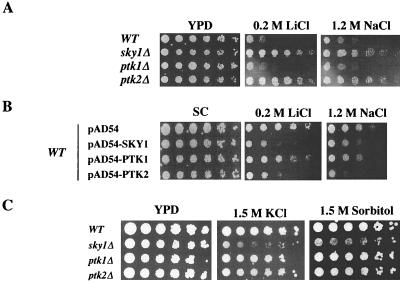

Ptk1p and Ptk2p belong to a subfamily of kinases that include Hal4p and Hal5p, which are involved in regulating halotolerance. It is therefore not entirely surprising that in addition to spermine tolerance, PTK2 disruption also provokes resistance to NaCl and LiCl (21). We therefore tested whether disruption of SKY1 also confers tolerance to salt and osmotic insults. As shown in Fig. 6A, sky1Δ cells tolerated 0.2 M LiCl and 1.2 M NaCl, similar to ptk2Δ cells, while the growth of wild-type and ptk1Δ cells was severely inhibited. As would be expected, overexpression of Sky1p, Ptk2p, and, to a somewhat lesser extent, also Ptk1p increased the sensitivity of wild-type cells to LiCl and NaCl (Fig. 6B). Disruption of SKY1 but not of PTK1 and PTK2 resulted in sensitivity to osmotic shock caused by 1.5 M KCl and to a somewhat lesser extent by 1.5 M sorbitol (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

sky1Δ cells are tolerant to LiCl and NaCl and sensitive to osmotic shock. (A) Fivefold dilutions of wild-type (WT), sky1Δ, ptk1Δ, and ptk2Δ cells were spotted on YPD plates containing 0.2 M LiCl or 1.2 M NaCl. (B) Fivefold dilutions of wild-type cells transformed with the expression vector pAD54, encoding Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p. The resulting transformants were spotted on MLSC plates with similar additives as in A. (C) Fivefold dilutions of wild-type, sky1Δ, ptk1Δ, and ptk2Δ cells were spotted on YPD plates containing 1.5 M KCl or 1.5 M sorbitol.

Sky1p and Ptk2p modulate spermine tolerance via two distinct signaling pathways.

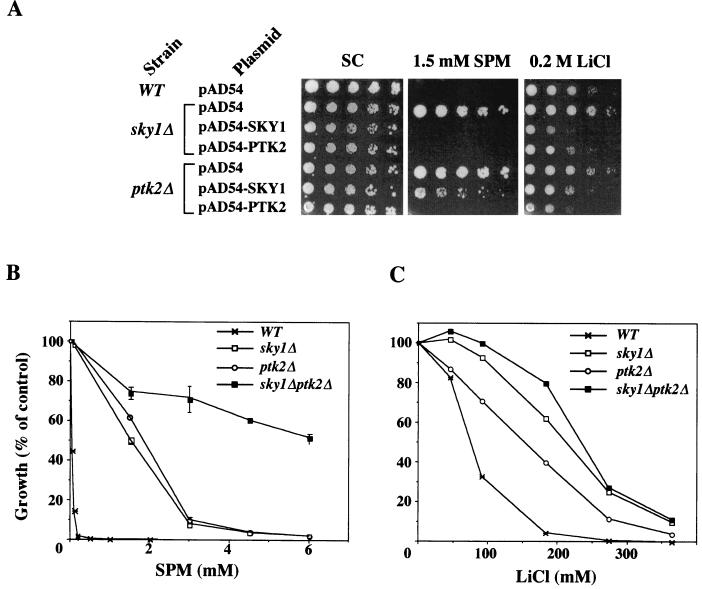

We next set out to test for possible relationships between Sky1p and the previously described polyamine uptake-regulating kinase Ptk2p. Overexpression of Sky1p and Ptk2p in sky1Δ cells suppressed their spermine- and LiCl-tolerant phenotype (Fig. 7A). In contrast, overexpression of Sky1p in ptk2Δ cells efficiently suppressed their tolerance to LiCl but only partially suppressed their tolerance to spermine (Fig. 7A). The greater ability of Ptk2p to suppress the spermine-tolerant phenotype of sky1Δ cells compared to the ability of Sky1p to suppress the tolerance of ptk2Δ cells suggested that Ptk2p may act downstream from Sky1p.

FIG. 7.

Complementation analysis reveals that SKY1 and PTK2 act in two parallel signaling pathways. (A) sky1Δ and ptk2Δ cells were transformed with empty vector (pAD54) or with constructs that overexpress Sky1p or Ptk2p. Spermine tolerance of the resulting transformants was determined by drop tests in MLSC plates containing 1.5 mM spermine and SC plates containing 0.2 M LiCl. The growth of wild-type (WT), sky1Δ, ptk2Δ, and sky1Δ ptk2Δ double mutant cells was tested in the presence of the indicated concentrations of spermine (B) and LiCl (C).

To address this possibility more directly, we tested the spermine and LiCl tolerance of sky1Δ ptk2Δ double mutant cells. As shown in Fig. 7B, the spermine tolerance displayed by sky1Δ ptk2Δ double mutant cells was actually greater than additive. This result strongly implies that the two kinases act in parallel pathways. In the case of salt tolerance, the situation is somewhat less clear, since although being higher than that of the single mutant, the LiCl tolerance displayed by the double mutant cells was lower than that expected from simple additivity (Fig. 7C). The spermine and LiCl tolerance of the ptk1Δ ptk2Δ double mutant was not significantly different from the tolerance displayed by ptk2Δ cells (not shown).

Sky1p modulates spermine and salt tolerance without significantly altering Pma1p activity.

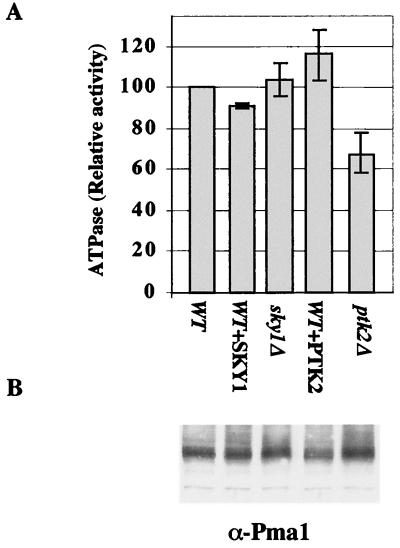

It is tempting to suggest that the phenotype observed in sky1Δ or ptk2Δ cells or in cells overexpressing Sky1p or Ptk2p is mediated at least in part by changes in membrane potential. The major generator of membrane potential in yeast cells is the plasma membrane H+/ATPase Pma1p. We therefore measured Pma1p activity in sky1Δ cells, in ptk2Δ cells, and in wild-type cells overproducing Sky1p or Ptk2p. Pma1p activity was slightly increased in sky1Δ and slightly decreased in Sky1p-overproducing cells (Fig. 8A). Although these minimal changes were consistently observed, it is unlikely that these changes are the cause of the observed SKY1-related phenotypes. In contrast, Pma1p activity was quite significantly increased in Ptk2p-overproducing cells and significantly decreased in ptk2Δ cells (Fig. 8A). Since these changes in Pma1p activity are not accompanied by changes in the amount of the protein (Fig. 8B), it is possible that Ptk2p modulates Pma1p activity by specific phosphorylation of the protein that is already located at the plasma membrane (4, 8). As it was demonstrated that Pma1p is activated by glucose (7, 8, 48), we replaced sorbitol with glucose in the lysis buffer to ensure that the enzyme is maintained in its active state. The use of glucose in the lysis buffer gave essentially the same results.

FIG. 8.

H+-ATPase activity in plasma membranes of sky1Δ and ptk2Δ cells and in wild-type cells overproducing Sky1p or Ptk2p. Plasma membranes were prepared from wild-type (WT) cells transformed with empty vector (WT) or SKY1 (WT+SKY1) or PTK2 (WT+PTK2)-overexpressing vectors and from sky1Δ or ptk2Δ cells transformed with empty vector (sky1Δ and ptk2Δ, respectively). ATPase activity was assayed (A) and the Pma1p protein was determined (B) as described under Materials and Methods.

LiCl sensitivity provoked by overexpressed Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p requires Ppz1p but not Ena1p.

The yeast RNA-binding protein Np13p, which contains a glycine/arginine-rich domain and has been implicated in mRNA export (26) and rRNA processing (45), was shown to be a substrate of Sky1p and of metazoan SRPKs (49). Although no other protein has been identified so far as a direct target of Sky1p, there are additional yeast proteins, some involved in splicing, which contain serine/arginine-rich or glycine/arginine-rich segments which can therefore be considered potential substrates of Sky1p. These include Mud2p, an ortholog of the human splicing factor U2AF65 (1), and Gbp2p, an RNA-binding domain-containing protein (25). Our present results demonstrate that in contrast to sky1Δ cells, np13Δ, mud2Δ, and gbp2Δ cells fail to grow in the presence of 1.5 mM spermine (not shown). This result suggests that the role of Sky1p in mediating spermine tolerance is manifested through phosphorylation of either other SR proteins (49) or a non-SR protein(s) or due to redundancy in the function of yeast SR proteins.

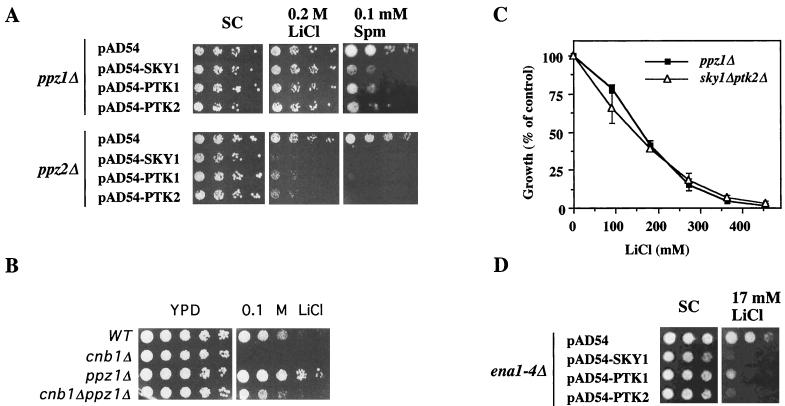

We screened the yeast genome database for additional proteins that contain SR segments and therefore may be substrates for Sky1p. We noted that the protein phosphatases Ppz1p and Ppz2p, which were implicated in modulating salt tolerance (43), contain SR-rich segments located at their amino-terminal regions that may be phosphorylated by Sky1p. This region of Ppz1p was demonstrated to have a regulatory role (5). Although ppz1Δ and ppz2Δ cells were not resistant to toxic levels of spermine (not shown), we set out to test for possible involvement of the Ppz phosphatases in mediating the effect of Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p by their overexpression in ppz1Δ or ppz2Δ cells. While overexpression of the three kinases increased spermine sensitivity in both ppz1Δ and ppz2Δ cells, increased LiCl sensitivity was observed only in ppz2Δ cells (Fig. 9A). Therefore, it appears that the ability of the three kinases to increase salt sensitivity may at least in part be mediated by Ppz1p. Since the ppz1 mutant is very tolerant to LiCl, it can be argued that it may not be possible to detect alteration in the displayed tolerance. That this is not the case is clearly demonstrated by the reduced LiCl tolerance displayed by ppz1Δ cells with a deletion of the gene encoding the calcineurin-regulatory β subunit CNB1 (Fig. 9B). If Sky1p and Ptk2p both act through Ppz1p, it is expected that the salt tolerance displayed by ppz1Δ cells will be at least equivalent to that displayed by sky1Δ ptk2Δ double mutant cells. As shown in Fig. 9C, both cell types displayed practically identical tolerance to a range of LiCl concentrations, suggesting that both kinases fulfill their role via Ppz1p.

FIG. 9.

PPZ1 but not PPZ2 or ENA1 is required for the effect of SKY1, PTK1, and PTK2 on lithium tolerance phenotype. (A) ppz1Δ and ppz2Δ cells were transformed with the expression vector pAD54, encoding Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p. The resulting transformants were spotted in fivefold dilutions on SC plates containing 0.2 M LiCl or MLSC plates containing 1.5 mM spermine. (B) The PPZ1 gene was deleted from cnb1Δ cells. The growth of the resulting double mutant cells was compared to that of wild-type (WT), cnb1Δ, and ppz1Δ cells. (C) Effect of LiCl concentration on the growth of ppz1Δ and sky1Δ ptk2Δ double mutant cells. (D) ena1-4Δ cells were transformed with an empty pAD54 vector or with this vector encoding Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p, and the growth of the resulting transformants was tested on plates contains 17 mM LiCl as in panel A.

The Ppz phosphatases have been suggested to regulate cation efflux by downregulating the plasma membrane Na+/ATPase Ena1p, leading to sodium and lithium hypersensitivity (43). ENA1 is the first and only gene of four tandemly arranged related genes, ENA1 to ENA4, that is induced upon exposure to LiCl and NaCl. Deletion of ENA1 results in cellular hypersensitivity to LiCl and NaCl (11, 13). We therefore overexpressed Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p in ena1-4Δ cells and tested for LiCl sensitivity (Fig. 9D). Interestingly, overexpression of each of the three kinases further increased the LiCl sensitivity of the ena1-4Δ cells, suggesting that Ppz1p mediates the effect of the tested kinases via a mechanism that is different from that involved in the suppression of ENA1 expression.

DISCUSSION

Using a highly specific genetic screen that is based on spermine toxicity, we have demonstrated that Sky1, a recently identified yeast SR kinase, is involved in regulating polyamine transport. Two other serine/threonine kinases, Ptk1p and Ptk2p, were demonstrated to be regulators of polyamine transport in S. cerevisiae (20, 21, 38). These kinases belong to a yeast-specific subfamily of kinases that regulate the transport of salt ions and amino acids (15). Npr1p, another member of this kinase family, was also shown to affect polyamine uptake in addition to regulating amino acid permeases (54). Finally, Tpo1p, a member of the multidrug resistance family that was selected based on its homology to B. subtilis Blt, was demonstrated to transport polyamines into vacuoles (53). Here we demonstrate that a mutant strain with a disrupted SKY1 gene tolerates toxic concentrations of spermine in the growth medium. The spermine-tolerant phenotype of sky1Δ cells was completely reversed by transfection of the wild-type SKY1 gene, while the catalytically inactive Sky1p mutant in which lysine-187 was converted to alanine failed to restore spermine sensitivity. Furthermore, overexpression of Sky1p in wild-type cells increased their sensitivity to spermine. We have demonstrated that deletion of SKY1 confers tolerance to spermine by dramatically reducing its uptake by the cells. Deletion of SKY1 also dramatically inhibited the uptake of spermidine and putrescine. Kinetic analysis demonstrated that disruption of SKY1 significantly reduced the Vmax of spermidine uptake and increased the Km.

We demonstrate here that, as in the case of ptk2Δ cells (17, 18), sky1Δ cells also tolerate both LiCl and NaCl. While increasing salt tolerance, SKY1 disruption but not PTK2 disruption increased sensitivity to osmotic shock caused by 1.5 M KCl or 1.5 M sorbitol. These observations suggest that both Ptk2p and Sky1p are involved in regulating salt homeostasis but only Sky1p is involved in regulating osmolarity.

Overexpression of Ptk2p in sky1Δ cells and of Sky1p in ptk2Δ cells both restored spermine sensitivity. However, the effect of Ptk2p in sky1Δ cells was more profound than that of Sky1p in ptk2Δ cells. To some extent this result suggests that Ptk2p may act downstream of Sky1p. To determine more directly the relationships between these two kinases, we generated sky1Δ ptk2Δ double mutant cells and tested their tolerance to spermine and lithium. Since the spermine tolerance displayed by the double mutant cells was even greater than additive, we conclude that the two kinases act in two parallel signaling pathways. In the case of LiCl, the situation is less clear, since although being greater than that displayed by the two single mutants, the tolerance of the double mutant was clearly less than additive.

A prominent possibility is that Sky1p and Ptk2p affect the membrane potential. The proton gradient at the plasma membrane generated by the Pma1p H+/ATPase is an important determinant regulating the uptake and excretion of various ions. Since the effect of SKY1 deletion or Sky1p overexpression on Pma1p activity is very minimal, it is unlikely that Pma1p mediates the effect of Sky1p. In contrast, Pma1p activity is significantly increased in Ptk2p-overproducing cells and significantly decreased in ptk2Δ cells. This suggests that, at least in part, Ptk2p affect spermine and ion transport by altering membrane potential.

Sky1p, which was recently identified as the only SRPK of S. cerevisiae, may function like its metazoan counterparts in mRNA maturation by regulating splicing or transport of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (49). Therefore, it is possible that the effect of Sky1p on the process of polyamine transport may be mediated through its effect on splicing or RNA transport. In such a case, it can be expected that the deletion of SR-containing splicing factors may also result in a spermine-tolerant phenotype. Although only Np13p has so far been directly demonstrated to be a substrate for Sky1p, additional splicing-related proteins that contain SR-rich segments are encoded in the yeast genome. We have tested npl3Δ cells and cells containing disruptions of the genes encoding two additional putative Sky1p substrates, Gbp2p and Mud2p, for their ability to tolerate a toxic concentration of spermine. None of these deletion mutants tolerated spermine. These results may indicate that the tested genes are not involved in regulating spermine uptake, that there is redundancy in the function of these genes, that phosphorylation by Sky1p actually inhibits the activity of these proteins, which may act as inhibitors of the spermine transport (in such a case, one should expect that their overexpression, rather than their deletion, will confer spermine tolerance), or that other SR-containing proteins (splicing related or not) or proteins that lack SR segments mediate the effect of Sky1p. In line with the fourth possibility, we have noted that Ppz1p and Ppz2p, two protein phosphatases previously demonstrated to be important determinants of salt tolerance in S. cerevisiae, contain SR-rich segments in their amino-terminal regions. We demonstrate here that overexpression of Sky1p as well as of Ptk1p and Ptk2p in ppz1Δ and ppz2Δ cells increased spermine sensitivity. In contrast, overexpression of these proteins increased LiCl sensitivity only in ppz2Δ cells, suggesting that Ppz1p is required for mediating the ability of these three kinases to increase LiCl sensitivity. In contrast, the ability of these kinases to increase spermine sensitivity may be mediated by either of the two Ppz proteins or by a completely different mediator. To account for the first possibility, the deletion of both PPZ genes may be required to prevent the ability of the overexpressed kinases to increase spermine sensitivity. These possibilities as well as the possibility that the Ppz phosphatases are directly phosphorylated by Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p are under investigation.

In the case of the induced sensitivity to lithium, it was tempting to speculate that Ppz1p mediates the action of each of the three kinases via its ability to suppress ENA1 expression and thus reduce lithium efflux. However, since overexpression of Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p in ena1-4Δ cells increased their LiCl sensitivity, we conclude that, if at all, Ppz1p mediates the effect of these kinases only partially via modulation of Ena1p activity. It is possible that the effect is manifested by regulating other components involved in modulating ion transport across the plasma membrane (such as the Trk1-Trk2 potassium transporters 10, 23, 27) or into vacuoles. Ptk1p and Ptk2p are related to two other yeast protein kinases, Hal4 and Hal5, that were demonstrated to regulate the Trk1-Trk2 transporters (34). However, if Ptk1p and Ptk2p and the presently identified kinase Sky1p are capable of modulating the Trk1-Trk2 potassium transporters, they do it in a manner opposite that manifested by Hal4p and Hal5p. This possibility is also under investigation.

Although Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p are likely to display different site specificities, they appear to similarly modulate spermine and salt tolerance. This is likely due to their ability to phosphorylate the same proteins or proteins that belong to the same signaling pathway. Identification of the substrates of these kinases is a major focus of the present studies. Although Sky1p, Ptk1p, and Ptk2p appear to act similarly, there are some notable differences between them. Ptk1p affects spermine and salt tolerance only when overexpressed. It has been suggested that Ptk1p affects vacuolar transporters (53). PTK1 disruption only marginally affects sensitivity to norspermine, a toxic polyamine analog (21), and does not confer tolerance to a toxic spermine concentration (Fig. 2C). Ptk2p and Sky1p differ in two aspects: sky1Δ cells but not ptk2Δ cells display sensitivity to osmotic shock provoked by 1.5 M KCl and, to a lesser extent, by 1.5 M sorbitol, and ptk2Δ cells displayed about a 35% reduction in Pma1p activity, while increased Pma1p activity was measured in Ptk2p-overproducing cells. In contrast, a marginal reduction or increase in Pma1p activity was noted in Sky1p-overproducing and in sky1Δ cells, respectively (Fig. 8).

While Northern blot analysis revealed that SKY1 mRNA is normally expressed in sptC mutant cells, sequence analysis of SKY1 DNA (amplified by PCR using sptC and wild-type DNA as templates) demonstrated that these transcripts encode a mutant protein in which leucine-301 was converted to phenylalanine. The mutated leucine is an invariant residue fully conserved in catalytic domain VI of all SRPKs and clk/sty SRPKs (12, 37).

The present study expands our understanding of intracellular signaling that regulates the process of polyamine and ion transport in yeast cells. However, additional studies are required in order to achieve comprehensive understanding of the underlying signaling pathways. Moreover, the identity of the plasma membrane polyamine transporters is still an enigma. Identification and isolation of these transporters are major goals of our present studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. W. Slayman and K. Allen for anti-Pma1p antibody; A. Rodriguez-Navarro for the ena1-4Δ cells; and O. Giladi, J. Gerst, M. Marash, and N. Wender for their help and valuable discussions.

This study was supported by a grant from the Leo and Julia Forchheimer Center for Molecular Genetics at the Weizmann Institute of Science and by a research grant from the Jean-Jacques Brunschwig memorial fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abovich N, Liao X C, Rosbash M. The yeast MUD2 protein: an interaction with PRP11 defines a bridge between commitment complexes and U2 snRNP addition. Genes Dev. 1994;8:843–854. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byers T L, Wechter R, Nuttall M E, Pegg A E. Expression of a human gene for polyamine transport in Chinese-hamster ovary cells. Biochem J. 1989;263:745–752. doi: 10.1042/bj2630745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casero R A, Jr, Mank A R, Saab N H, Wu R, Dyer W J, Woster P M. Growth and biochemical effects of unsymmetrically substituted polyamine analogues in human lung tumor cells 1. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;36:69–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00685735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang A, Slayman C W. Maturation of the yeast plasma membrane [H+]ATPase involves phosphorylation during intracellular transport. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:289–295. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.2.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clotet J, Posas F, de Nadal E, Arino J. The NH2-terminal extension of protein phosphatase PPZ1 has an essential functional role. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26349–26355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S. A guide to the polyamines. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eraso P, Portillo F. Molecular mechanism of regulation of yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase by glucose. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10393–10399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estrada E, Agostinis P, Vandenheede J R, Goris J, Merlevede W, Francois J, Goffeau A, Ghislain M. Phosphorylation of yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase by casein kinase I. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32064–32072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiske C H, Subbarow Y. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J Biol Chem. 1925;66:375–400. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaber R F, Styles C A, Fink G R. TRK1 encodes a plasma membrane protein required for high-affinity potassium transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2848–2859. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.7.2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garciadeblas B, Rubio F, Quintero F J, Banuelos M A, Haro R, Rodriguez-Navarro A. Differential expression of two genes encoding isoforms of the ATPase involved in sodium efflux in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:363–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00277134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanks S K, Quin A, Hunter T. The protein kinase family: conserved features and deduced phylogeny of the catalytic domains. Science. 1988;241:42–51. doi: 10.1126/science.3291115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haro R, Garciadeblas B, Rodriguez-Navarro A. A novel P-type ATPase from yeast involved in sodium transport. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:189–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81280-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heaton M A, Flintoff W F. Methylglyoxal-bis(guanylhydrazone)-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cells: genetic evidence that more than a single locus controls uptake. J Cell Physiol. 1988;136:133–139. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041360117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter T, Plowman G D. The protein kinases of budding yeast: six score and more. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:18–22. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Polyamine transport in bacteria and yeast. Biochem J. 1999;344:633–642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Polyamine transport in Escherichia coli. Amino Acids. 1996;10:83–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00806095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser C, Michaelis S, Mitchell A. Methods in yeast genetics. 4th ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakinuma Y, Maruyama T, Nozaki T, Wada Y, Ohsumi Y, Igarashi K. Cloning of the gene encoding a putative serine/threonine protein kinase which enhances spermine uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;216:985–992. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaouass M, Audette M, Ramotar D, Verma S, De Montigny D, Gamache I, Torossian K, Poulin R. The STK2 gene, which encodes a putative Ser/Thr protein kinase, is required for high-affinity spermidine transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2994–3004. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaouass M, Gamache I, Ramotar D, Audette M, Poulin R. The spermidine transport system is regulated by ligand inactivation, endocytosis, and by the Npr1p Ser/Thr protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2109–2117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko C H, Gaber R F. TRK1 and TRK2 encode structurally related K+ transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4266–4273. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunkel T A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lalo D, Stettler S, Mariotte S, Gendreau E, Thuriaux P. Organization of the centromeric region of chromosome XIV in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:523–533. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee M S, Henry M, Silver P A. A protein that shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm is an important mediator of RNA export. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1233–1246. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madrid R, Gomez M J, Ramos J, Rodriguez-Navarro A. Ectopic potassium uptake in trk1 trk2 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae correlates with a highly hyperpolarized membrane potential. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14838–14844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandel J L, Flintoff W F. Isolation of mutant mammalian cells altered in polyamine transport. J Cell Physiol. 1978;97:335–343. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040970308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marton L J, Pegg A E. Polyamines as targets for therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;35:55–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maruyama T, Masuda N, Kakinuma Y, Igarashi K. Polyamine-sensitive magnesium transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1194:289–295. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCloskey D E, Casero R A, Jr, Woster P M, Davidson N E. Induction of programmed cell death in human breast cancer cells by an unsymmetrically alkylated polyamine analogue. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3233–3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCloskey D E, Yang J, Woster P M, Davidson N E, Casero R A., Jr Polyamine analogue induction of programmed cell death in human lung tumor cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell J L, Judd G G, Bareyal-Leyser A, Ling S Y. Feedback repression of polyamine transport is mediated by antizyme in mammalian tissue-culture cells. Biochem J. 1994;299(Pt. 1):19–22. doi: 10.1042/bj2990019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mulet J M, Leube M P, Kron S J, Rios G, Fink G R, Serrano R. A novel mechanism of ion homeostasis and salt tolerance in yeast: the Hal4 and Hal5 protein kinases modulate the Trk1-Trk2 potassium transporter. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3328–3337. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murakami Y, Matsufuji S, Kameji T, Hayashi S, Igarashi K, Tamura T, Tanaka K, Ichihara A. Ornithine decarboxylase is degraded by the 26S proteasome without ubiquitination. Nature. 1992;360:597–599. doi: 10.1038/360597a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murakami Y, Matsufuji S, Miyazaki Y, Hayashi S. Destabilization of ornithine decarboxylase by transfected antizyme gene expression in hepatoma tissue culture cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13138–13141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nayler O, Stamm S, Ulrich A. Characterization and comparison of four serine- and arginine-rich (SR) protein kinases. Biochem J. 1997;326:693–700. doi: 10.1042/bj3260693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nozaki T, Nishimura K, Michael A J, Maruyama T, Kakinuma Y, Igarashi K. A second gene encoding a putative serine/threonine protein kinase which enhances spermine uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:452–458. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Packham G, Cleveland J L. Ornithine decarboxylase is a mediator of c-Myc-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5741–5747. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pegg A E. Polyamine metabolism and its importance in neoplastic growth and a target for chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1988;48:759–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pegg A E, Poulin R, Coward J K. Use of aminopropyltransferase inhibitors and of non-metabolizable analogs to study polyamine regulation and function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;27:425–442. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(95)00007-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pegg A E, Shantz L M, Coleman C S. Ornithine decarboxylase as a target for chemoprevention. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1995;22:132–138. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posas F, Camps M, Arino J. The PPZ protein phosphatases are important determinants of salt tolerance in yeast cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13036–13041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramotar D, Popoff S C, Gralla E B, Demple B. Cellular role of yeast Apn1 apurinic endonuclease/3′-diesterase: repair of oxidative and alkylation DNA damage and control of spontaneous mutation. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4537–4544. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.9.4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russell I D, Tollervey D. NOP3 is an essential yeast protein which is required for pre-rRNA processing. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:737–747. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakata K, Fukuchi-Shimogori T, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. Identification of regulatory region of antizyme necessary for the negative regulation of polyamine transport. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:415–419. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seiler N, Dezeure F. Polyamine transport in mammalian cells. Int J Biochem. 1990;22:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(90)90332-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serrano R. In vivo glucose activation of yeast plasma membrane ATPase. FEBS Lett. 1983;156:11–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siebel C W, Feng L, Guthrie C, Fu X D. Conservation in budding yeast of a kinase specific for SR splicing factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5440–5445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki T, He Y, Kashiwagi K, Murakami Y, Hayashi S, Igarashi K. Antizyme protects against abnormal accumulation and toxicity of polyamines in ornithine decarboxylase-overproducing cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8930–8934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabor C W, Tabor H. Polyamines. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:749–790. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tobias K E, Kahana C. Exposure to ornithine results in excessive accumulation of putrescine and apoptotic cell death in ornithine decarboxylase overproducing mouse myeloma cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1279–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tomitori H, Kashiwagi K, Sakata K, Kakinuma Y, Igarashi K. Identification of a gene for a polyamine transport protein in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3265–3267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vandenbol M, Jauniaux J C, Grenson M. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae NPR1 gene required for the activity of ammonia-sensitive amino acid permeases encodes a protein kinase homologue. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:393–399. doi: 10.1007/BF00633845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Withee J L, Sen R, Cyert M S. Ion tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking the Ca2+/CaM-dependent phosphatase (calcineurin) is improved by mutations in URE2 or PMA1. Genetics. 1998;149:865–878. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.2.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xie X, Tome M E, Gerner E W. Loss of intracellular putrescine pool-size regulation induces apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 1997;230:386–392. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeakley J M, Tronchre H, Olesen J, Dyck J A, Wang H Y, Fu X D. Phosphorylation regulates in vivo interaction and molecular targeting of serine/arginine-rich pre-mRNA splicing factors. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:447–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]