Abstract

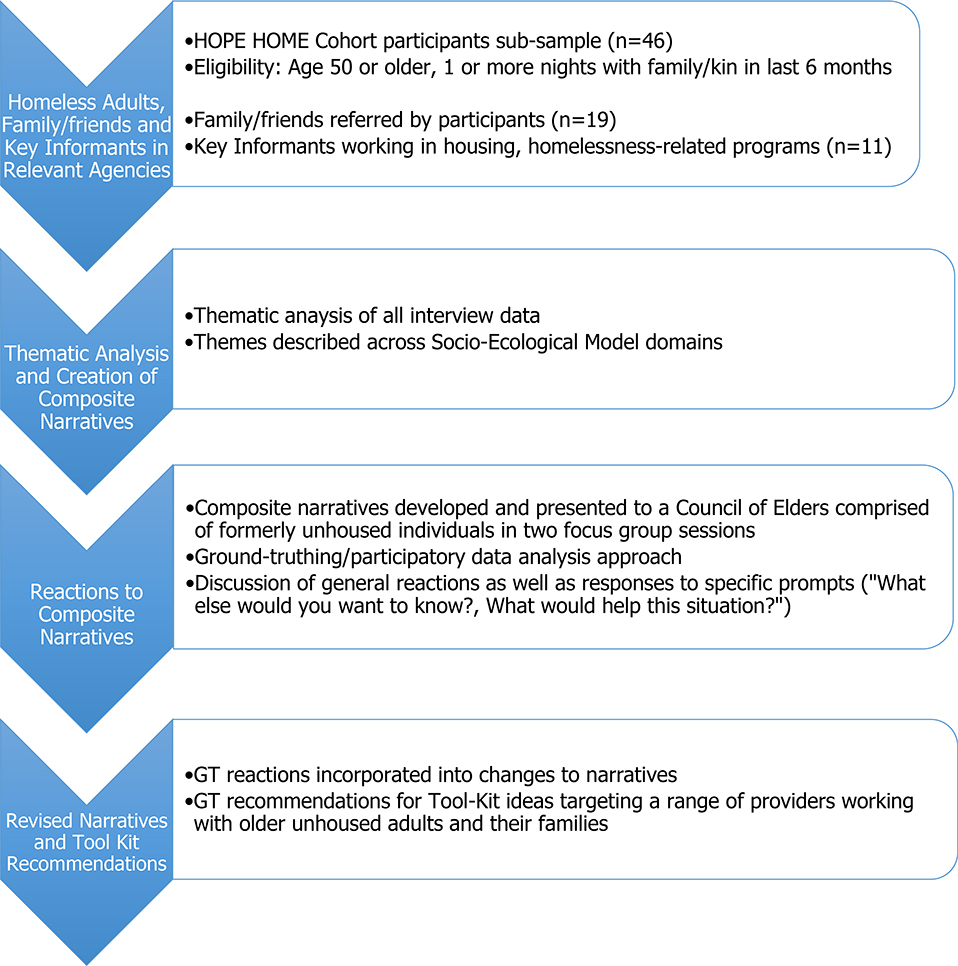

Many older homeless adults temporarily stay with family or friends, yet little is understood about these experiences. We conducted a multimethod qualitative study of older homeless adults in Oakland, California. First, we conducted in-depth interviews among older adults experiencing homelessness with recent stays with a housed family member or friend (n=46), hosts (n=19), and program key informants (n=11). Next, we developed thematic summaries in the form of character-based composite stories, which were presented to a Council of Elders with lived experiences of homelessness, to explore their reactions. This process is referred to as ground-truthing, a form of participatory data analysis. Predominantly, participants were African American men. Barriers included structural factors (discrimination), policy (lease restrictions), community (violence), interpersonal factors (power dynamics), and individual factors (health problems). Factors enhancing stays included inter-generational support and leveraging resources. Ground-truthing discussions reinforced and expanded upon findings (e.g., importance of neighborhood identity, training needs, how self-improvement affects readiness to live with others).

Keywords: homelessness, aging, participatory research, qualitative methods

The proportion of homeless adults age 50 and older has grown at a rate exceeding the general population for the past two decades.1 In Alameda County, California, the median age of homeless single adults is 51 years, an increase of eight years since 2003.2 In a recent study in Oakland, California, almost half (44%) of homeless adults aged 50 and older had their first episode of homelessness after the age of 50.3 The deleterious effects of homelessness on health, including accelerated decline, are well documented4 and have led to initiatives to identify effective approaches to prevent and end homelessness.5 One underexplored area relates to the role of family and friends in providing both respite from homelessness and longer-term housing stability. Individuals experiencing homelessness stay with family and friends commonly before, during, and following homelessness episodes. Many rely on their networks to prevent or delay episodes of homelessness or to exit homelessness. A recent population-based study of homelessness in Alameda County indicated that the living arrangements preceding homelessness often were with family or friends.

Because homelessness is a contested social problem shaped by a wide range of sociological, political, and structural economic drivers,6 research to understand and address it benefits from interdisciplinary approaches and methodological innovations. Our methodological approach builds on an interdisciplinary literature related to participatory research methods, such as community-based participatory research (CBPR)7–8 and participatory mapping.9 Among these participatory methodological approaches is ground-truthing, in which researchers engage community members in interpreting findings, most often findings related to Geographic Information System (GIS) or other mapped images.9–11 This direct form of ground-truthing is applied, for example, to characterize species diversity or to gauge water access, but it is also applied more broadly, to reach locations and populations whose views are often not included in community-based survey method approaches.10,12 Ground-truthing then emerges as a method for field-based work: it is thought of as walking the ground to see for oneself if what has been told is true. Ground-truthing methods have been applied to environmental justice issues, in which community partners gather data about the proximity of sensitive receptors—concentrations of people who may be at increased risk for poor health, such as the elderly, young children, and people with chronic health conditions related to pollution sources.13–14 Ground-truthing reflects the view that there will be local knowledge both out of reach to, and potentially in conflict with, the data collected through traditional research studies by those living outside the experience. In ground-truthing, participants focus on the plausibility of the data, but also collaborate on dissemination strategies (e.g., messaging). As part of a qualitative research study, itself embedded in a longitudinal cohort study of older homeless adults, we included a ground-truthing (GT) sub-study. The study aims include: understanding the factors influencing older homeless adults’ ability to live with housed family members from the perspective of both older homeless adults and their family members, to understand these factors from the perspective of programmatic and policy key informant and to identify ideas to improve the connection of homeless individuals with families and friends.

Using themes identified during data analysis of in-depth interviews with older homeless adults, we created composite stories about their lives to enable descriptive summaries that conveyed the complexities of the overall study themes, such as the historical and present-day socio-ecologic pressures affecting the housing experiences of participants. For example, we describe themes that addressed discrimination in housing and service access, barriers embedded in subsidized housing policies, criminal justice experiences and complex health problems. We plan to use these stories in a toolkit for training and dissemination, in which we will target a range of social and health care service providers working with older homeless adults and their families. This approach is based on a health communication method referred to as narrative health promotion, 15–17 which we have applied in previous work in HIV prevention,18 diabetes prevention,19 and lead poisoning prevention.20 In such an approach, researchers create stories based on qualitative interview data or working with stakeholders to develop stories based on lived experience with a health problem or its determinants. We drew on multiple themes to develop a set of composite stories without incorporating the specific details of any one participant’s individual story and discussed these stories in focus groups for reactions. Narrative health promotion has been widely applied to patient-provider communication, with studies indicating positive impacts on patient-provider relationships, provision of culturally sensitive care, and behavior change.21–23 We first present the overall study methods, and then explore the composite story development process and the ground-truthing components.

Methods

Overview.

The HOPE HOME cohort study is an ongoing longitudinal study of 350 older homeless adults, initially recruited between July 2013 and June 2014 in Oakland, California.3 A large proportion of the cohort have frequent contact with family members; approximately one-third had overnight visits with family lasting a week or longer in the prior six months; most expressed a willingness to live with family and a belief that their family members would allow them.

In 2018–2019, we purposively sampled a sub-set of HOPE HOME participants for the qualitative Family Assisted Housing study which examined older homeless adults’ recent living experiences with family or friends.6 To be eligible, participants had to report spending at least one night with a housed family member (or close friend) in the prior six months. As part of the study, we interviewed homeless participants and, separately, the family members or friends with whom they stayed. In addition, we conducted key informant interviews with front-line providers, housing and homeless service leaders, and policymakers.

We employed a three-tiered, multimethod qualitative approach that included (1) in-depth interviews with older adults experiencing homelessness and their hosts (family and friends who hosted participants); (2) narrative-based thematic summaries representing common participant experiences; and (3) focus group reactions to these summaries (“ground-truthing”) with a community-based Council of Elders, which we refer to as the participatory data analysis or ground-truthing component of the study. The primary goal of the ground-truthing component was to evaluate the extent to which the main themes we identified across socio-ecological domains rang true to stakeholders from the community of older adults with a lived experience of either their own, or their family members’, homelessness in Oakland, California. This approach falls within the sphere of participatory data interpretation and is one of the identified forms of participatory data analysis essential to ensuring that research findings are not given to communities in the absence of procedures for community input.24–26 Conducting data analysis and data interpretation of findings through an engagement process with stakeholders has been highlighted as an underexplored area of participatory research, in that the participatory process often breaks down or loses steam once an intervention has been shaped and recruitment goals met.24, 27–28

Data collection methods.

Using a semi-structured interview guide, we conducted 46 qualitative interviews with older homeless adults, lasting 60–90 minutes. Interviews focused on participants’ physical and mental health, their experience of homelessness, and their experience of short and long-term stays with family and friends while homeless. We asked participants for their permission to contact family members or friends with whom they had stayed. We assured them that we would not share any of the information that they gave us with their family/friends and vice versa. If participants granted permission, we asked them to give us names and contact information of their hosts. We conducted 19 in-depth qualitative interviews with these family or friends, focusing on their experience of providing short and long-term stays. We conducted 11 key informant interviews with a range of providers, policymakers, and leaders in affordable housing, homelessness services, and homeless policy. Consistent with the social-ecological model, we explored the individual, relationship, community, and policy factors (e.g. shelter policies, housing regulations) that contribute to motivations for short and long-term stays, as well as their benefits and challenges.29 We conducted the interviews in private offices at a community-based nonprofit organization serving low-income adults and/or where participants lived. We provided a $25 gift card for a local retailer for the HOPE HOME participant, family and friend interviews, and focus group participants and a $50 gift card for key informant interviews. All interviews were audio-taped. A professional transcriptionist transcribed the recordings verbatim and de-identified participant information. The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco approved all study activities.

Data analysis.

Consistent with participatory data analysis methodologies, we began data analysis simultaneously with data collection.30 We engaged in three interpretative activities for the full sample of interviews conducted: (1) data summarizing and consensus data analysis discussions, (2) codebook development and coding, and (3) data synthesis and manuscript development. First, interviewers created detailed summaries immediately after the completion of each interview. These summaries included the basic outline of the content participants described in the interviews as well as theoretical memoing, in which interviewers offer thematic impressions and insights.31–32 The data analysis team met to discuss the transcripts and accompanying summaries in order to develop the preliminary codebook.

Using this iterative process, we revised the codebook three additional times until no further changes were necessary. We also established inter-rater reliability. We entered coded transcript data into the Atlas.ti Qualitative Data Analysis Software (version 7.5.17; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany). In the final stage of data analysis, we identified salient themes emergent in consensus discussions and data coding processes, with a focus on themes’ scope, inter-relationship.33,34 The range of experiences of the study investigators allowed for a detailed analysis of results. All investigators are university-affiliated researchers focused on homelessness and marginalized populations. The majority of study investigators, including the lead authors, have been working with older homeless adults for over a decade, one as a clinician providing care to this group and one with a family member who experienced homelessness off and on for decades.

Composite stories.

The purpose of the composite stories was to provide a deeper understanding of the types of unmet needs as well as successful strategies for addressing the barriers to and facilitators of housing older homeless adults with family members or friends. To initiate the story development, one of the authors reviewed thematic summaries and notes from the data analysis meetings to select initial themes reflecting examples of barriers and enablers to staying with family or friends using the pre-specified socio-ecologic categories (individual, interpersonal, community, and policy levels). Then, through a series of data analysis meetings, we selected themes across the socio-ecological categories to include in the composite stories. For example, one of the themes we included related to male family members who, while experiencing homelessness, felt shame and emasculation about needing to stay with family/friends (the composite story, Joe). In this story, we also included the community-level theme of over-crowding (lack of affordable housing, shelter capacity), resulting in couches and other non-private spaces are available for family stays. We prioritized themes based on whether it was relevant across different types of participants (e.g. hosts, homeless person), and whether it encompassed more than one socio-ecologic level. Different members of the study team then developed composite narratives, each story including multiple thematic elements. We developed nine composite stories, five of which are included (Table 1).

Table 1:

Examples of Composite Narrative Results Including Socio-Ecologic Themes and Selected Quotes

| Themes Across Socio-Ecologic Levels* | Example quotes from participant interviews related to the themes** | Composite Narrative |

|---|---|---|

| INDIVIDUAL 1-An older man experiencing homelessness not wanting to stay due to feeling of shame and ‘being a burden’. 2-Older men often find it hard to not be the man of the house and must fit into a family dynamic he is inexperienced with. COMMUNITY 3-Over-crowding - leaving only couches and other non-private spaces for stays. |

1, 2: “It made me feel ashamed, I feel shameful, you know, because I’m supposed to be taking care of my business at my own place...That was more me, it was more me.”

1, 2: “I bring what I can but they always, I mean, they, they taking care, they do what they have to do. I’m always welcome that they got food. I’m welcome to it, but I always try to have my own, you know. Try not to go there hungry and I’m, I try to get out of there as soon as I can, not laying around.” 1: “I say, ’Yeah, but what happened to me I done to myself and I need to fix it myself.’” |

Joe is 58 years old and lost his housing 3 years ago when he lost his job in a warehouse. He’s living in a tent under the freeway. His sister lives in a 2-bedroom apartment in Oakland with her husband and two teenage children. Joe has stayed at his sister’s for 6 nights in the last 2 years. He says the reason he doesn’t stay more often is because he doesn’t want to be a burden to her and her family. She said that he could stay more often. |

| INDIVIDUAL 1-Participant prefers local services but there are placements farther away, and they may be isolating. COMMUNITY 2-Pressures from social service agencies for placements in other cities makes people feel they are being forced out of their communities, where they prefer to stay. POLICY 3-Housing shortages and high rents lead to the only available placements are far from participants’ communities. |

1, 3: “...we talked to our brother last night, he said he was going to start coming to get us. He’s trying to get us to move up there (Sacramento, 2 hours away) but I told him, “I’m not leaving my church, I’m not.” He said, “Well, you ain’t got to pay but $800.” I said, “I’m not leaving my church, D----, the Lord going to find me a place out here that I can pay for by myself.”

2: “It was difficult because the lady, she was very, very persistent. She kept, she called me like three times a week to come pick up my keys.”[alluding to the participant’s social worker pressuring participant to take a place in another county just as he was getting offered a place in Oakland where he wanted to be.] |

Richard is a 65 year old currently living on the street. He doesn’t want to live at a shelter. He has received his medical care at a clinic in Oakland for 15 years and likes his doctor. He would like to live with his ex-wife and have her take care of him - -She could get paid to be his care giver/ IHHS worker. However, his case manager has recommended senior subsidized housing in Fresno instead. |

| INDIVIDUAL 1-Risk to substance use recovery with move “back” to the old neighborhood. COMMUNITY/POLICY 2-Gentrification, widespread evictions, and limited available and affordable housing in the neighborhood. COMMUNITY/POLICY 3-Experiences of racial discrimination. 4-Experiences of police profiling. |

1: I: “What’s wrong here?”

P: “Because I know, I know too many people. Too much drugs and as long as I’m here the longer I’m going to get high.” 2: “Prices first. And new people comin’ in, old people goin’ out. A little harder now. Basically that. People that were working down here, it’s not no more. Other people comin’ in, buyin’ up the property now.” 3: “I went to the city council meetin’ one time and I was asked to leave. Now, you have to –you can’t be sayin’ that, you got to leave. But I’m tellin’ the truth. See. And you don’t want to hear the truth. Just like they said, you can’t handle the truth! These people out here –and you’re talkin’ about Black Lives Matter –black lives ain’t the only lives that matter. All lives matter. But the –it’s prevalent to us because we the ones getting killed.” 4: “So I didn’t know how to get there, and these guys were walkin’, and they didn’t want to wait for the bus so I walked with ‘em up there. I gets to the BART station, police up there actin’ crazy, like he wanna take us back to jail, ‘cause one of them dudes was doin’ somethin’, and they –one of –take us all to jail, so I gets up on the BART, the police came up there and they’s askin’ us our names and stuff, they knew we was from Santa Rita. Any time –they knowin’ people from Santa Rita. Seem like they just know who get released and everything.” |

Tasha is a 56-year-old African-American woman who is in recovery from years of heroin use. She recently lost her part-time job at her church and is staying at the shelter. Her cousin has an apartment in West Oakland and has offered her the living room couch. She would like to move there but worries about being back in her old neighborhood. She has heard the police are targeting a lot of old residents because the neighborhood is getting expensive and upscale. |

| INDIVIDUAL 1-Loss of family home triggering homelessness. 2-Lack of privacy in someone else’s space can increase feelings of anxiety, frustration and isolation. INTERPERSONAL 3-Relationship strain when moving into someone else’s world. COMMUNITY/POLICY 4-Over-crowding - leaving only couches and other non-private spaces for stays. 5-Predatory housing market creates family pressures to sell houses. |

1: I: But I mean, did it [family home] get sold, or is family there?

P: Well, I think they sell it, I’m pretty sure they did. But it was auctioned off, like that.” 2, 3: “Yeah, and she, I mean, it was some nights I stayed there and, it was understood from the beginning, no drinking, no drugs, no smoking, no, no this, no that so that was understood but I felt that if I wanted to, let’s just say, she’s very protective. 4: “I’m basically homeless. But I go from homeless to my brother house, from my brother house to homeless. He got a family of his own so it’s basically crowded.” 5: “She sold the house out from under me, she put a restraining order out on me so I had to leave the house, and then she put the house up for sale and then cashed the Escrow check.” |

Brenda is a 63 year old African American woman who became homeless last year when her mother died and the house she lived in all her life was sold by her brother. She’s been staying on and off with different friends ever since. She could live with her niece, but it’s all the way on the other side of town and she’s worried about being isolated. She also thinks her niece’s apartment is too crowded, often with people she doesn’t know. |

| INDIVIDUAL 1-Older adults’ experiences of cognitive and physical decline and fear of being vulnerable on street during and after experiences of homelessness. INTERPERSONAL 2-Stays may jeopardize finances of the host. COMMUNITY/POLICY 3-Rent vulnerability widespread across family. |

1: “You know, this is a 24-hour job mentally and physically with me now. Used to be mental not physical, too. But I’m doing a lot better compared to when I, when I had the surgery on the hip, even after I had the fall, the hip is the one hasn’t given me any problems, so that’s a blessing in disguise. But now I got to work on the other parts of the body and they’re not going anywhere.” 2: “It’s hard for me, you know what I mean, because I pay $600...that leaves me with not very much to buy food. So..I mean, I be like really stretching it.”[host]. 3: “Yeah. Because I realized when I got there, that I could better handle the rent than she could. With my disability, the money I’m makin’, she was strugglin’, so I basically took the burden off her.” |

Howard is 68 year old man, and has been homeless off and on for many years. He uses a walker to get around and is worried that his health is declining. He feels that he is more forgetful these days. His son lives with his girlfriend in a one bedroom apartment in San Leandro and receives workers compensation because of his bad back. Howard and his son are talking about Howard moving in, but his son’s landlord says he will increase the rent if anyone moves in. |

Due to length, not every theme presented has a quote provided in the table.

Text denotes an ‘I’ for interviewer and a ‘P’ for participant. All quotes presented in the Table are drawn from the participant interviews, although themes analyzed from hosts and key informant interviews supported the identified themes presented.

Ground-truthing.

For the ground-truthing component, we recruited from the Council of Elders, a standing advisory group to a community shelter comprised of older aged individuals with lived experiences of homelessness. The Council members are older men and women with lived experience of severe poverty and/or homelessness who engage in advocacy work and leadership development. Council members are 95% African American, two-thirds woman, and all but one is over age 60 years. Because of the unique challenges that older homeless adults experience the Council group were well positioned to provide important insights into these experiences. The Council, run by one of the authors, is a program of St Mary’s Center, a community-based organization that provides services (including emergency shelter) and advocacy to older adults living in poverty and homelessness in Oakland, California. Council volunteers were asked to participate in a focus group to provide reactions to and feedback about the composite stories and assist in providing ideas for a toolkit. We conducted two focus group sessions between May and July 2018 with the ground-truthing group, each lasting two hours, moderated by one of the study team members, and attended by additional study team notetakers. Discussion questions for each of the nine stories were developed in team meetings and are included in detail in Appendix 1: What in this story strikes you? What more do you want to know more about in the story about [name]? What’s missing? What is the biggest challenge of this story? What might help them?

In these ground-truthing sessions, participants acted as expert interpreters, consistent with the process of participatory data analysis.24, 34–35 The discussion included prompts to help identify contraindications to staying with family or friends, the challenges faced in experiences of providing and receiving housing with family or friends, and successful strategies the members were aware of that might be used by families to house homeless family members. The ground-truthing group also reflected on strategies to overcome community and policy-related constraints that impede family-assisted housing that were relevant to the composite stories. Box 1 presents toolkit ideas based on summaries of these reflections.

Box 1. Toolkit Ideas Emerging From GT Discussions with a Focus on Older Adults: Social Services, Clinical and Policy Levels.

| Job training programs, with a focus on jobs that can be held by older adults (Social Services) |

| Long-term support programs for addiction recovery including those with older ages in mind (Social Services) |

| Re-orientation assessment for those moving from street homelessness or encampment environments to living with family (Social Services) |

| Preparedness assessment when considering leaving a community, to get a ‘better’ deal but in a new unfamiliar place (Social Services). |

| Community planners help those facing homelessness work with community groups to address gentrification (Social Services) |

| Financial planning for those in aging family homes/how not to lose the home (Social Services) |

| Counselling to make decisions about re-locating at this age/circumstances (Social Services) |

| Case managers address the aging in place gap for this population (Social Services) |

| Re-orientation training to co-locate when crowding may be an issue (Social Services) |

| Use of social risk factor screening including readiness to leave homeless environment, relationship to new settings, and strategies to avoid conflict with a focus on challenges among older adults (Social Services) |

| Transportation and accessibility of transportation (Social Services) |

| Budget/planning for higher rent; understand pros and cons of different living arrangements (Social Services) |

| Planning for living with a relative, to aid informed decisions/role reversals/shifts in roles and expectations (Social Services) |

| Risk assessment for individuals to avoid for losing place on housing list (Clinical and Social Services) |

| IHSS worker eligibility/good situations to use it (Clinical and Social Services) |

| Lease management and end of life planning (e.g. when the lease holder is an older adult, the other HH members also need planning). Screening tools for the risks associated with losing housing when there is an older generation passing, and accompanying resources to mitigate the risks (Clinical and Social Services) |

| Counseling to increase options for establishing social connections among those of a similar age, like church to offset isolation (Clinical and Social Services) |

| Knowledge about getting more individual care, including things like in-home care, and rules re these programs (Clinical and Social Services) |

| Counselling to address negative thought patterns (Clinical) |

| Geriatricians engage in assessment of housing circumstances/ refer for planning (Clinical) |

| Regional responses that mitigate against isolation from re-locations (Policy) |

| Establishing eligibility for senior housing, even if in family home (Policy) |

| Shallow subsidies to help reduce economic burden on host families (Policy) |

Results

The homeless participant sample included 46 people who reported staying with housed family members for a day or longer in the prior six months. Three-quarters were men and 87% were African American, 11% were White, and 2% were Latino. Almost half, 45%, first became homeless at or after the age of 50. Approximately 70% of the homeless participants stayed with family or friends for longer than one week. Among 19 host participants, 15 were women and four men; 17 were African American, one was White, and one did not report. There were 10 ground-truther participants, half were women and the majority were African American (90%).

We identified the following primary themes in the analysis (Table 1): importance of family relations (friends are also a common source of contact), family-level economic precarity, privacy needs, shame, masculinity, inter-personal conflict, housing regulation barriers, gentrification, benefits of pooling resources, health problems including mental health and use of addictive substances, and inter-generational support. In some cases, stays could be mutually beneficial in the sense of leveraging social support or economic resources. Stays often provide respites from conditions and stressors of homelessness and can provide important opportunities for intergenerational engagement. However, homeless participants often internalize feelings of shame irrespective of family/friends’ behavior, and for men, this often takes the form of feeling emasculated. The importance of interpersonal conflicts as a damaging experience associated with family and friend housing stays was identified as a barrier, as well as a general lack of mental health services that exacerbated challenges even among families with good intentions. In instances where privacy was a challenge, participants indicated additional strains on interpersonal dynamics. Past substance use or criminal justice history strained interpersonal dynamics as well, often with resultant judgmental criticism from family/friends. Another piece of the puzzle is that descriptions of local housing policies focused primarily on nuclear families and did not provide eligibility to broader social networks, thereby presenting on-going challenges to stays. Gentrification practices in the community, resulting in few affordable housing options or crowding, resulted in displacements to more outlying areas, putting participants at risk for danger when public transportation between housing and services was subsequently limited, as many needed to travel in higher-crime areas on foot. Hosts’ health problems and daily health care needs (as well as those of the homeless family member), often related to limited mobility or chronic illness, or emerging health problems such as cognitive decline, were identified as presenting challenges for hosts, many of whom reported health problems that were not well controlled.

Ground-truthing reactions.

Below, we summarize five of the nine stories that we developed along with the salient discussion points from the ground-truthing (GT) focus groups. These five reflected the themes that occurred most frequently.

Joe

Joe is 58 years old and lost his housing three years ago when he lost his job in a warehouse. He’s living in a tent under the freeway. His sister lives in a two-bedroom apartment in Oakland with her husband and two teenage children. Joe has stayed at his sister’s for six nights in the last two years. He says the reason he doesn’t stay more often is because he doesn’t want to be a burden to her and her family. She said that he could stay more often.

When the elders discussed Joe’s situation, there was tension about whether or not he was deserving of his family’s assistance. Specifically, the group questioned whether Joe should receive pity, compassion, and support, or whether he should just “be a man” and solve his own problems. One participant commented, ”I think Joe makes a lot of excuses. Two years ago, he lost his job. A lot of people lose jobs, why don’t get they a new one?” This was consistent with the view among some GT participants that since he had been homeless for a few years, he ought to know some of the strategies to get off the street and earn some income. Some interpreters implied that if he wasn’t off the street, and was back and forth at his sister’s, he (presumably) was not serious about trying to leave the street. Others in the group expressed more concern about the toll of losing a job at an older age, especially on one’s motivation and mental health:

He is a senior.... isn’t clear to me how long he had been on that job. Had been there for a long time, stable, secure. To go out and compete against younger people to get another job. Could create a mental health issue and make him less and less able to function.

The group described some general concerns about families providing housing when there was a power imbalance among family members. Several participants described their own experiences when staying with family members, which they felt had thwarted their independence or challenged established family roles. This went hand in hand with observations that only one’s self could create the change needed to get off the street. This later tension was particularly noted among men who expressed feelings about expectations to behave “like a man,” that were either self-imposed or emerged from family dynamics. The following quotation conveys how power imbalances or changes in interactions and roles can disrupt successful stays with family: “But you can’t control everything when people come together and live in a household. If you have that control you shouldn’t have it. Too much control over someone else’s life with the pressure that you put under them. Don’t smoke, use drugs in my house, bring a prostitute. [T]oo much control over another person. The whole man thing.”

Finally, some expressed concern about whether Joe would make things worse for his sister ([this situation] “put[s] a lot of pressure on the sister”). For example, if she had financial stressors, as with the following reflection, “Sister might not be doing that good herself. I don’t want to be in that position [of asking]: ‘Do I have the tools necessary to help you? Do I have the money to feed and care for? Do I have the right to tell you what to do?’”

Richard

Richard is a 65 year-old man currently living on the street. He doesn’t want to live at a shelter. He has received his medical care at a clinic in Oakland for 15 years and likes his doctor. He would like to live with his ex-wife and have her take care of him—she could get paid to be his care giver/In Home Support Services (IHSS) worker. However, his case manager has recommended senior subsidized housing in Fresno (about two to three hours away) instead.

There was consensus among the GT group that they needed more information to determine if moving out of the area was the right decision for Richard. Several in the group had themselves moved away, most said it had not been a good experience, and all had returned (although this likely also reflects the fact that those who had good experiences moving away would not be in this Oakland-based group). Ground-truthing members were concerned that it might be isolating for Richard to move outside the area. “You go to Fresno you gonna be by yourself, first of all. You’re not gonna know nobody, you ain’t gonna have a worker, no doctor, no nothin.” However, some also insisted on the importance of the practical benefits he might have re-locating, as suggested here: “It’s about wants and needs. You may want to stay in Oakland. But you can’t stay in Oakland and you need a place. You may want a milkshake but you need water. It’s wants and needs. That could have been the quickest way for that man to get off the street, and Fresno wide open—come on, we got a place for you. Wants and needs.”

The group discussed their own experience with case managers who had suggested similar moves. Several participants reported having felt pressured to re-locate to obtain housing (e.g., distant locations but also those within an hour or two of Oakland but with lower costs, such as Pleasanton). “Yeah, ‘cause the reason I’m sayin’ that, ‘cause I just got one yesterday for a Pleasanton subsidized housing, a one-bedroom. I’m not gonna take it, but it’s the same thing, like they said. ‘Move down here’, somewhere—that’s what they’re [case managers] doin’. They want to move everybody way out there.” Despite these concerns, the group wanted Richard to say yes to the relocation application even if he might refuse the housing later, reiterating the importance the group attached to keeping options open and considering a range of options for what was in his best interest. There was overall the view among participants that when options were present, they should be kept available as long as possible, because few resources were available to those experiencing homelessness.

The GT group demonstrated an extensive understanding of socio-ecological factors affecting those experiencing homelessness, as well as factors specific to moving in with family or friends. One GT participant described the range of systems-based challenges confronting Richard, and emphasized the importance of having a qualified social worker to help navigate this terrain as summarized here:

Now, the truth of the matter is, when it comes to getting subsidized housing, you do not want to miss the chance to apply for housing. You don’t say no to the opportunity, the appointment. You don’t say no to the application. Because who knows, by the time that application hits, where you’re gonna be? But you want to be able to have that opportunity to say no, when you have a real chance of living in Fresno. Don’t say no to the application. A subsidy, the value of a subsidy for a senior that makes $885 is like—the lottery. So you have to compare movin’ to Fresno to actually livin’ a reasonable life. You’d have to compare it to bein’ able to take care of yourself independently with the subsidy, to what I’m givin’ up.

Finally, there was some discussion about what was required to be eligible as a home health care worker, which is a type of supportive health worker, who provides personal care to those with disabilities or house-bound. The group had some concerns about how family members could be disqualified possibly if they had criminal justice system involvement, with one participant saying they were worried about if his wife could be eligible, “It’s just that she can’t go. ‘Cause she can’t pass this IHSS worker, she can’t pass the background check.”

Tasha

Tasha is a 56-year-old African American woman who is in recovery from years of heroin use. She recently lost her part-time job at her church and is staying at the shelter. Her cousin has an apartment in West Oakland and has offered her the living room couch. She would like to move there but worries about being back in her old neighborhood. She has heard the police are targeting a lot of old residents because the neighborhood is getting expensive and upscale.

The group reactions to Tasha’s story were similar to their reactions to Joe’s in that they focused on personal responsibility. In discussing the story where she had lost her job, there was the presumption that it was due to something she did. The group wanted to know why she lost her job and also if she had kids. There was disagreement as to whether Tasha should focus on substance use recovery, and if she could do so in her old neighborhood. The group debated her need for more help/mental health support, as reflected in this this comment: “I was sayin’, true enough, everything about what you were sayin’ about she’s bein’ really scared about bein’ in the old neighborhood. But that’s somethin’ that she gotta make a decision on wherever she is—you could take the ghetto out of somebody, but you can’t take the ghetto—how do that go?” There was also the observation that Tasha may be too vulnerable to successfully adjust to a new neighborhood, yet there was concern that the old neighborhood could trigger substance use. Several members of the group found that this resonated personally with them.

There was consensus that Tasha should go to a shelter and get services from there, that this would be more stabilizing long-term, compared with staying on a couch in her former neighborhood. The group noted that there was an assumption in the story that staying with family or friends would be safer for her, while in fact it would depend on the circumstances of the proposed stay. The group believed that aging itself makes the recovery process much harder, and that it would take Tasha a long time to be stable in her sobriety. They implied that she should not get derailed from these efforts with a problematic environment/living situation. “She’s 56 years old. Once you hit your 50s, it’s way harder to be in recovery, stay in recovery.”

Tasha’s story led to a discussion of gentrification in the community as a result of recent development, with group members making specific reference to racial differences between older neighborhood residents and newcomers. Group members expressed their frustration that African Americans were losing houses as a result of systematic exploitation practices (e.g., foreclosure resulting from predatory lending, housing speculation) as well as from families being forced to sell. The group also acknowledged that the police were moving homeless people out of community areas that had been gentrified, and this was disruptive to the broader community. There was a strong view across the group that there was a big change in neighborhood housing availability, as can be seen in this exchange:

P: And I’m tellin’ you, boy, the area I live in, if you had been there 30 years ago, it wasn’t the same. I’m talkin’ about color-wise.”

I: So when we’re talking in Oakland, what does that mean?

P: The police are cleanin’ up.”

Brenda

Brenda is a 63-year-old African American woman who became homeless last year when her mother died and the house she lived in all her life was sold by her brother. She has been staying on and off with different friends ever since. She could live with her niece, but the niece lives all the way on the other side of town and Brenda is worried about being isolated. She also thinks her niece’s apartment is too crowded, often with people she doesn’t know.

There was agreement in the group that Brenda “lacked preparedness” for her mother’s passing. “Well, she’s living with her mother, her mother has to be at least 83. And so if she’s depending up on her mother—maybe her mother was ill, terminally, why didn’t she secure something for herself, find out what’s gonna happen to the house, get on a senior housing list, make preparations for herself in the event that her mother did pass.“ However, this critical view was tempered by discussions about the complex family dynamics of selling a home and the conflicts that often arise among family members when presented with the collective financial strain of saving a family home from foreclosure, with a more compassionate view towards Brenda emerging, as in the following:

P: I’ve seen this so many times here recently, where the situation is exactly like this, to where a brother who had authority sold the house after the parents died—the mother and father put everything in this particular individual’s name, because he took care of ‘em in their last days. So when he died everything was in his name. He gave the rest of ‘em a little somethin.

P: Concerned about her mental state being able to handle change. At 63—addict or not—wonder about her mental health.

The discussion of Brenda generally mirrored a consistent theme across the interview data in which the original study participants seemed to internalize blame and personal responsibility, or kept it focused on their own family structures, in terms of housing losses following the death of a parent. There was very little attribution of housing losses to community-wide pressures or structural inequities that have disproportionately affected African American property owners in West Oakland, as the area has become more gentrified.36 It was also striking that so many in the group felt that Brenda’s situation was real and widespread—both the precursor to homelessness experienced through a sudden loss of a family home through the death of a parent, but also the precariousness of finding a new living situation, while still early in the grieving process.

Howard

Howard is a 68-year-old man and has been homeless off and on for many years. He uses a walker to get around and is worried that his health is declining. He feels that he is more forgetful these days. His son lives with his girlfriend in a one-bedroom apartment in San Leandro and receives workers compensation because of his bad back. Howard and his son are talking about Howard moving in, but his son’s landlord says he will increase the rent if anyone moves in.

During the discussion about Howard, there was agreement that Howard’s stay with his son could work in the short-term, and that maybe he could help finance a bigger place to share with his son. There was some hope for positive outcomes expressed by the group, but also some strong views that Howard could lose his freedom. “You don’t move your father into your home if you have a girlfriend.” There was a strong sense that there are fewer and fewer choices for people like Howard, being older and in poor health as seen here: “Their choices are so limited. In truth—to be able to get granted any of those opportunities are scarce. We don’t have enough of ANY kind of beds. Here is Howard who is 68 and homeless. His health is truly deteriorating. Is his choice between another year outside with a walker or attempting to take this opportunity that his son is giving him? We are up against these two difficult decisions. We don’t have that many choices.”

Ground-truthing participants brought up the fact that being under stress or in need can make you want to cling to family, even if only temporarily. Such a dynamic was viewed by the group as an important risk, which could result in a role reversal and shift in power dynamics that is not good for anyone. “When you are in need, it’s like you are a stranger—your family doesn’t know you in the same way.” But on the flip side, there was also recognition of the potential for such an arrangement to be mutually beneficial financially, if they could combine the workers compensation his son had with a caregiver stipend if his son provided care as an IHSS worker.

Discussion

In this paper we present a sequential exploration of themes related to the experiences of older homeless adults, their family and friends, and key informants regarding recent housing stays. We did this first, through thematic summaries using a socio-ecological framework and grounded theory, and second, with analysis of composite stories though a ground-truthing process during focus groups. One of the striking findings from this work relates to the ground-truthers’ resonance with the characters in the composite stories and their compassion towards them, which was offset by their reluctance to let go of the personal accountability they believed would be necessary for the characters’ stories to turn out well. It is possible that a strong alignment between their own narratives of overcoming hardship compelled the ground-truthers to focus on the individual responsibilities they assigned to the story protagonists. However, it is also possible that there was an internalization of structural drivers embedded in the stories, such as housing discrimination, racism, gentrification, and the marginalization of chronically economically depressed neighborhoods from access to services. These internalizations are consistent with the reactions to both Joe and Tasha’s stories in particular, wherein blame is prominent in the discussion as is a focus on personal responsibility for solving one’s own problems. These ground-truther discussions also reflected a rejection of the interdependence on others, even when the storyline also includes larger social forces, such as job loss and gentrification. This is consistent with Bourdieu’s social theory of symbolic violence, in which there is often an internalization of the explanations, stigmas, and blame that circulate in the dominant culture.37 This reliance on personal growth and strength-building, although individualized, can also be seen as a form of solidarity often found in addiction recovery programs. This recognition, however, should not discount the larger problem of personal responsibility narratives, which is that they focus on individuals fixing themselves rather than fixing systems to support individuals and communities.

Another interesting finding in the ground-truther reactions relates to the ambivalence toward potential displacement when new housing might be obtained, either across town (Brenda) or further out in adjacent counties (Richard). The ground-truthers commented on the considerable upheaval of displacement for older adults from such moves. They noted that their lives would become more difficult to navigate physically and emotionally as well as more isolated. The group expressed this concern forcefully, even as there was also acknowledgment of the importance of being practical about the benefits of stable housing. They also noted that many social service workers did not seem to be well-equipped to discuss the complexity surrounding such moves and their inherent trade-offs. This suggests that those who are already displaced for housing, such as the stories’ protagonists, are likely to be called upon to be “practical” in the face of the demands that, in exchange for not being homeless, they agree to move away from the communities they have lived in their whole lives. This assumption, that such individuals should agree to move from the communities they have lived in their entire lives, can be seen as a form of structural violence.38–39 “Practicality” in this context places this vulnerable group in the position to accept the opportunities to be provided for, regardless of the emotional and social costs. The inevitability of such a rationale, that scarcity should be reason enough to encourage the taking of housing offers, may be harmful, and the ground-truthers were ambivalent about this practicality-dominated perspective. These nuanced reactions were a direct result of the sequenced narrative-based data interpretations presented in this paper, which in turn led to toolkit ideas for social services agencies (such as screening for social risk factors such as social isolation as well as training staff to be sensitive to the risks associated with older adults moving out of the area- which is to say moving away from home). It can also be noted that current policies put social service workers in a challenging position, of wanting to help their clients find housing, but only being able to do so if they displace people from their home communities to lower-cost areas.

We believe the ideas outlined in Box 1 can initiate a planning process for a toolkit that will provide a direct link between this form of participatory data interpretation and topics for the development of local policies to address determinants of homelessness or to ease the transitions to living more beneficially with host families or friends for older homeless adults. For example, the ground-truthing participants paid attention to individually-focused tips that could potentially help the characters in the stories and that could lead to broader program changes. In the first case, there were specific examples of recommended strategies to avoid difficult situations, such as staying away from areas of town that might trigger a return to substance use, getting out of an environment that had too much interpersonal conflict, or avoiding landlord complaints about overnight stays beyond what was specified on the lease. For community programs or policies, some of the suggestions related to creating support services to help families anticipate challenges to keeping a house once the elder generation has passed away or ensuring that social service providers are not placing older individuals in outlying communities without fully assessing the pros and cons of such a move. However, programs and policymakers must name and address the structural challenges, beyond simply providing toolkits for staff in resource strained social service agencies. In this way, social service workers might be better able to toggle successfully between individual experiences and systems-level barriers, to remediate internalization and focus on strengths and not blame individuals (or at least raise systemic issues so that policymakers can address them, as well). From a researcher’s perspective, illuminating the structural issues and concerns is possible, as structural perspectives are often buried within the data itself. We plan to engage the stakeholder organizations in discussion of these ideas, as for example, ideas on how to develop screening questions to understand what individuals have experienced intersecting across structural domains, rather than asking individual questions for each area.

By incorporating qualitative data findings with an interdisciplinary methodological approach to data interpretation that built narratives into the data analysis, we were able to add depth to our findings on the barriers and facilitators of older homeless adults staying with their family and friends. Using this iterative, participatory process, we received feedback from the ground-truther groups on our analysis of the qualitative data which, in turn, allowed us to move towards areas of priority for a toolkit for implementation. Similar to a study focused on interdisciplinary explorations of the social vulnerabilities affecting the lives of injection drug users in San Francisco,40 we employ a range of cross-qualitative-based methodological approaches, including qualitative interviewing, participatory engagement in data analysis, narrative-based health promotion, and ground-truthing. The sequencing of multiple qualitative methods presented here allows for first, an exploration of themes identified from qualitative interviewing about living with family and friends, and second, participatory data analysis with a ground-truthing group with lived experiences relevant to housing stays with family and friends among older homeless adults. Together, this approach provides a rich understanding of these themes and their implications for service delivery and policy. The use of composite narratives allowed for more explicit attention to and discussion of structural factors underlying many of the described lived experiences of participants and ground-truthers than a discussion of themes alone would provide. Although the methods we described are based on ground-truthing approaches, there are also other approaches to incorporate for sequential stakeholder input, including town hall meetings, standing community advisory boards, and community-based workshops with a wider range of stakeholders than we engaged in this study, some of which incorporate sustained engagement.

There are several limitations worth noting in this work. First, we were not able to interview the full sample of hosts to incorporate a wider range of perspectives, a reflection of the sampling strategy we felt was necessary to assure participants that we would contact hosts only with their explicit permission. Second, for the participatory data analysis process, bringing the Council of Elders into the development of the composite stories, rather than in the phase of responding to these stories, could have created a more comprehensive series of narratives and is a methodological approach that would benefit future work in this area.

Conclusion.

Staying with family and friends may provide an alternative to emergency shelters or living in unsheltered settings or, in some cases, a strategy to end homelessness. In our study, people with lived experience have key insights regarding the feasibility and appropriateness of this strategy, and provided critical contextual understanding of the realities of such respite housing. The development of the composite stories in this paper to summarize socio-ecologic themes for discussion, particularly those beyond the individual level (such as over-crowding/gentrification, housing policies or landlord suspicions that discourage staying with family for more than a couple of days), represents a novel approach to make more visible factors that are often hidden drivers of homelessness. Through this approach, we were able to identify strategies to build on the strength of networks to interrupt homelessness, both temporarily (i.e., in lieu of homeless shelters) and more permanently. The individuals with lived experience pointed out challenges to using this strategy, and their ideas present opportunities to develop policies to overcome these barriers. These insights can be useful to both front-line providers and to policymakers.

Figure 1:

Steps Undertaken in the Ground-Truthing Study

Abbreviations:

- GT

ground-truthing

Appendix 1. Interview Guide: Ground-Truthers Meetings

Preamble: “Thank you all for coming today. We brought you here because we want to hear your thoughts about a common experience: when an older adult has been homeless, stayed with their family or friends—for any amount of time. And also, we want to hear if you, or others you know, have offered housing to an older adult who has been homeless.

We have been interviewing older adults who have an experience of homelessness and who have stayed with family or friends. We also interviewed their family or friends who provide housing. Our goals for today are to get your insights to help us understand the stories that we have been hearing and to hear new stories. Your input will help us make recommendations to people who make decisions about housing to be sure that those people understand the good and hard parts about this experience, and that they make changes to improve on the good parts and reduce the hardships.

We have some stories that represent what we heard when we interviewed older adults who had been homeless and the people who hosted them. To protect privacy we are not sharing stories that happened to actual people. Instead, we have created stories that are based on what we have heard. We want to hear from you, your reactions to these stories.”

“I’m going to read each sample scenario and give you a few minutes to think about – we left you some space so you can right down some thoughts for our discussion.” Column 1 of the Scenarios were handed out to GT members.

I. Re-storied Narratives

| Narrative | Potential Follow-Up Questions | Potential Follow-Up Questions (if not noted in discussion) |

|---|---|---|

| Joe is 58 years old and lost his housing 3 years ago when he lost his job in a warehouse. He’s living in a tent under the freeway. His sister lives in a 2-bedroom apartment in Fruitvale with her husband and two teenage children. Joe has stayed at his sister’s for 6 nights in the last 2 years. He says the reason he doesn’t stay more often is because he doesn’t want to be a burden to her and her family. She said that he could stay more often. |

Discuss broadly and then present back what is there and not there- these may be helpful: ○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What’s missing? What more do you want to know more about in Joe’s story? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Joe? ○ Why do you think he did he not ask to stay more? ○ How could Joe stay in the house? |

○ I’d want to know what Joe is like and how he interacts with others living there. What is his relationship like with his sister and her husband, the children? ○ How would his behaviors change things? Does he use drugs? ○ Where would he sleep? |

| Sam stays with his niece and she wants him to give money towards the rent-- which he does. But he also wants to use some of this money for his storage locker. Sam found out that his niece was not paying her rent on time. He was getting more angry with her all the time and she was getting mad at him too. He felt he was in-between a rock and a hard place and decided to move on. | ○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What more do you want to know more about in Sam’s story? ○ What’s missing? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Sam? |

○ Do you think this is a common type of story of family members not getting along when someone who is an older homeless adult comes to stay? ○ What kind of conflict do you think would be most likely here- words, yelling, threatening? ○ What do you know about how people who move in with family or friends deal with storage for their stuff, their possessions? ○ Do you think that Sam and his niece could have worked out some kind of a plan with the money and his storage locker? |

| Gladys is a single mom and works 40 hours a week. Her dad Tom just left the winter shelter and is staying with her. Tom offered to give her some of his SSI money every month. Gladys also asked Tom to help her out some with childcare for her school aged son. Gladys is worried that the landlord will find out that Tom is staying. The family is getting along fine and Tom enjoys staying with Gladys and his grandson. | ○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What more do you want to know more about in Gladys story? Or about Tom? ○ What’s missing? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Gladys or Tom or both of them? |

○ Do you think the landlord had a right to know about Tom staying? ○ Have you heard of people being asked to do lots of childcare or other chores in exchange for a place to stay? ○ What about people being asked to do chores or work that is hard on them physically or emotionally? |

| Brenda is a 63 yo AA woman who became homeless when her mother died and the house she lived in all her life was sold by her brother last year. She’s been staying on and off with different friends ever since. She could live with her niece, but it’s all the way on the other side of town and she’s worried about being isolated. She also thinks her niece’s apartment is too crowded, often with people she doesn’t know. | ○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What more do you want to know more about in Brenda’s story? Or about her? ○ What’s missing? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Brenda? |

○ How will this kind of move affect Brenda’s connections/friends? ○ How will Brenda access services in her niece’s neighborhood? ○ How might this living arrangement affect her sense of her own independence? Or finding peace? |

| Richard is a 65 year old currently living on the street. He doesn’t want to live at a shelter. He has received his medical care at a clinic in Oakland for 15 years and likes his doctor. He would like to live with his ex-wife and have her take care of him - -She could get paid to be his care giver/ IHHS worker. However, his case manager has recommended senior subsidized housing in Fresno instead. | ○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What more do you want to know more about in Richard’s story? Or about him or his health? ○ What’s missing? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Richard? |

○ Have you heard people discuss this model of care – where someone is a paid caregiver of someone else- to help with their health? If so who brings it up? ○ What do you think about the case manager’s suggestion? ○ What do you know about people moving out of the area to get senior subsidized housing? ○ What else do you think about IHHS and how it works for families when someone moves in since they were homeless? Is it too crowded to do? Does it affect leases in harmful ways (e.g. equal contribution, bigger lease requirements)? |

| Howard is 68 year old man, and has been homeless off and on for many years. He uses a walker to get around and is worried that his health is declining. His son lives with his girlfriend in a one bedroom apartment in San Leandro and receives workers comp because of his bad back. Howard and his son are talking about Howard moving in, but his son’s landlord says he will increase the rent if anyone moves in. | ○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What more do you want to know more about in Howard’s story? Or about him or his son? ○ What’s missing? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Howard and his son? |

○ What should be worked out before Howard and his son take any steps to move Howard in? ○ Have you heard about landlords doing this? ○ Who would be responsible for paying extra? ○ What if the building did not have elevator or other helps for the father? ○ What about the impact on other bills that may increase? |

| Tasha is a 56-year-old African-American woman who is in recovery from years of heroin use. She recently lost her part-time job at her church and is staying at the shelter. Her cousin has an apartment in West Oakland and has offered her the living room couch. She would like to move there but worries about being back in her old neighborhood. She has heard the police are targeting a lot of old residents because the neighborhood is getting expensive and upscale. |

○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What more do you want to know more about in Tasha’s story? Or about her? ○ What’s missing? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Tasha? |

○ Why is she worried about being back in her old neighborhood? ○ Do you think that her feelings about being triggered re her use in her neighborhood are like how you have heard about before? Do you think the way she gets support for her recovery services are affected by the gentrification and her access to drug treatment services? ○ What might help her keep connected to her community resources and support given the gentrification/changes? ○ How do you think it will make her feel to be staying on the couch and it being crowded? ○ Do you think the services in her community are changing? Where can she go? Access to food? Public transport? Treatment and low-income. |

| Roy is a 65-year-old African-American man who is homeless after his release from three years in prison for possession of marijuana with intent to sell. This was his third, and he hopes last, experience doing time. His youngest daughter has an apartment in Stockton with an extra room and Roy would like to move in, but the apartment is next to elementary school and Roy is worried that would violate the terms of his parole. | ○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What more do you want to know more about in Roy’s story? Or about him? What’s more do we want to know/what’s missing? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Roy? |

○ Would you want to know more about the rules of his parole? Do you think others also worry about violations as they relate to this possible move? ○ Is that common that people have to travel back here for their community or do they stay away? E.g. coming back to see people, access services, neighborhood, churches? ○ What have you heard about people moving to places a few hours away such as Stockton or the Central Valley? How might that relocation affect homeless folks? |

| Bob is a 65 year old man from West Oakland had a fall and is now in the hospital. He feels that he is more forgetful these days. His case manager just found an apt in E Oakland but he grew up in West Oakland and was hoping to stay with his brother who lives there. He is worried about getting lost in a new place he doesn’t really know. He feels that a new environment will push him over the edge in feeling the stress of keeping on top of all, but he also is not sure his brother, who is also in poor health, can handle anything else. | ○ What in this story strikes you? ○ What more do you want to know more about in Bob’s story? Or about him? What’s more do we want to know/what’s missing? ○ What is the biggest challenge of this story? ○ What might help Bob? |

○ What do you think about Bob’s concerns? His brother’s concerns? ○ What about the case worker’s suggestion? |

II. General Discussion Questions for the Narratives

Have you heard stories like this? What have you heard? What kinds of things were important? What about different ones you think we should hear about?

Reactions?

What more would you want to know about this person or this situation?

What is the biggest challenge of this story?

Are there opportunities here that you see?

What are some of the things that got in the way? Helped out?

Can you think of anything that could have helped this situation?

What can be a better way to get to a solution?

Make up your own story or modify one of these stories to make it better.

REFERENCES

- 1.Culhane Dennis P., Metraux Stephen, and Bainbridge Jay (2010). “The Age Structure of Contemporary Homelessness: Risk Period or Cohort Effect?” Penn School of Social Policy and Practice Working Paper, 1–28. Retrieved 5/20/20 (https://repository.upenn.edu/spp_papers/140): 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speiglman Richard, and Norris Jean C. (2004). “Alameda Countywide Shelter and Services Survey: COUNTY REPORT.” Retrieved February 5, 2020, from http://everyonehome.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/resources_HomelessCount04-1.pdf.

- 3.Author 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelberg Lillian and Linn Lawrence S. (1992). “Demographic Differences in Health Status of Homeless Adults.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 7(6): 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) Opening Doors Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness. Washington, DC,. (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Author. 2019.

- 7.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Rhodes S, Samuel-Hodge C, Maty S, Lux L, Webb L, Sutton SF, Swinson T, Jackman A and Whitener L (2004). “Community-Based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence.” Evidence Report Technology Assessment (Summ) August(99): 1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cacari-Stone Lisa, Wallerstein Nina, Garcia Analilia P., and Minkler Meredith (2014). “The Promise of Community-based Participatory Research for Health Equity: A Conceptual Model for Bridging Evidence With Policy.” American Journal of Public Health 104 (9): 1615–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadd James, Morello-Frosch Rachel, Pastor Manuel, Matsuoka Martha, Prichard Michele, and Carter Vanessa (2014). “The Truth, the Whole Truth, and Nothing but the Ground-Truth: Methods to Advance Environmental Justice and Researcher-Community Partnerships.” Health Education & Behavior 41(3): 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraão Marcia B., Nelson Bruce W., Baniwa João C., Yu Douglas. W., and Shepard Glenn. H. Jr (2008). “Ethnobotanical Ground-truthing: Indigenous Knowledge, Floristic Inventories and Satellite Imagery in the Upper Rio Negro, Brazil.” Journal of Biogeography 35(12): 2237–2248. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGuirt Jared T., Jilcott Stephanie B., Vu Maihan B., and Keyserling Thomas C. (2011). “Conducting Community Audits to Evaluate Community Resources for Healthful Lifestyle Behaviors: An Illustration From Rural Eastern North Carolina.” Preventing Chronic Disease 8(6): A149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams Terry T. 2004. “Ground-Truthing”. Orion Retrieved DATE from https://orionmagazine.org/article/ground-truthing/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akom Antwi., Shah Aekta, Nakai Aaron., and Cruz Tessa (2016). “Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) 2.0: How Technological Innovation and Digital Organizing Sparked a Food Revolution in East Oakland.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 29(10): 1287–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakibinga Pauline., Kabaria Caroline, Kyobutungi Catherine, Manyara Anthony, Mbaya Nelson, Mohammed Shukri, Njeri Anne, Azam Iqbal, Iqbal Romaina, Mazaffar Shahid, Rizvi Narjis, Rizvi Tayyaba, Rehman Hamid ur, Ahmed Syed A.K. Shifat, Alam Ornob, Khan Afreen Z., Rahman Omar, Yusuf Rita, Odubanjo Doyin, Ayobola Montunrayo, Fayehun Funke, Omigbodun Akinyinka, Owoaje Eme, Taiwo Olalekan, Diggle Peter, Aujla Navneet, Chen Yen-Fu, Gill Paramijt, Griffiths Francis, Harris Bronwyn, Madan Jason, Lilford Richard J., Oyobode Oyinlola R., Pitidis Vangelis., Albequerque Joao Porto de, Sartori Jo, Taylor Celia, Ulbrich Philip, Uthman Olalekan, Watson Samuel I., Yeboah Godwin (2019). “A Protocol for a Multi-site, Spatially-referenced Household Survey in Slum Settings: Methods for Access, Sampling Frame Construction, Sampling, and Field Data Collection.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 19(1): 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robillard Alyssa G. and Larkey Linda (2009). “Health Disadvantages in Colorectal Cancer Screening Among African Americans: Considering the Cultural Context of Narrative Health Promotion.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor Underserved 20(2 Suppl): 102–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gubrium Aline C., Fiddian-Green Alice, Lowe Sarah, DiFulvio Gloria, and Del Toro-Mejías Lizbeth (2016). “Measuring Down: Evaluating Digital Storytelling as a Process for Narrative Health Promotion.” Qualitative Health Research 26(13): 1787–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiddian-Green Alice, Gubrium Aline C., and Peterson Jeffery C. (2017). “Puerto Rican Latina Youth Coming Out to Talk About Sexuality and Identity.” Health Communication 32(9): 1093–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Author. 1999.

- 19.Author. 2015.

- 20.Author. 2009.

- 21.Briant Katherine J., Halter Amy, Marchello Nathan, Escareno Monica, and Thompson Beti (2016). “The Power of Digital Storytelling as a Culturally Relevant Health Promotion Tool.” Health Promotion Practice 17(6): 793–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vecchi De, Nadia Amanda Kenny, Dickson-Swift Virginia, and Kidd Susan (2016). “How Digital Storytelling is Used in Mental Health: A Scoping Review.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 25(3): 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiddian-Green Alice, Kim Sunny, Gubrium Aline C., Larkey Linda K., and Peterson Jeffery C. (2019). “Restor(y)ing Health: A Conceptual Model of the Effects of Digital Storytelling.” Health Promotion Practice 20(4): 502–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cashman Suzanne B., Adeky Sarah, Allen Alex J. 3rd, Corburn Jason, Israel Barbara A., Montaño Jaime, Rafelito Alvin, Rhodes Scott D., Swanston Samara, Wallerstein Nina, and Eng Eugenia (2008). “The Power and the Promise: Working With Communities to Analyze Data, Interpret Findings, and Get to Outcomes.” American Journal of Public Health 98(8): 1407–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Author. 2014.

- 26.Author. 2009.

- 27.Israel Barbara, Checkoway Barry, Schulz Amy, and Zimmerman Mark (1994). “Health Education and Community Empowerment: Conceptualizing and Measuring Perceptions of Individual, Organizational, and Community Control.” Health Education & Behavior 21(2): 149–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacQueen Kathleen M. and Auerbach Judith D. (2018). “It is Not Just About “The Trial”: The Critical Role of Effective Engagement and Participatory Practices for Moving the HIV Research Field Forward.” Journal of International AIDS Society. 21 Suppl 7: e25179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stokols D (1996). “Translating Social Ecological Theory into Guidelines for Community Health Promotion.” American Journal of Health Promotion 10(4): 282–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corrado AM, Benjamin-Thomas TE, McGrath C, Hand C, Laliberte Rudman D. Participatory Action Research With Older Adults: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis. Gerontologist. 2020. Jul 15;60(5):e413–e427. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz080. PMID: 31264680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaser Barney G. 1998. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montgomery P and Bailey PH (2007). “Field Notes and Theoretical Memos in Grounded Theory.” Western Journal of Nursing Research 29(1): 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandelowski Margarete. and Leeman Jennifer (2012). “Writing Usable Qualitative Health Research Findings.” Qualitative Health Research 22(10): 1404–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nierse Christi J., Schipper Karen, van Zadelhoff Ezra, van de Griendt Joos, and Abma Tineke A. (2012). “Collaboration and Co-Ownership in Research: Dynamics and Dialogues Between Patient Research Partners and Professional Researchers in a Research Team.” Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy 15(3): 242–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clarke Charlotte L., Wilkinson Heather, Watson Julie, Wilcockson Jane, Kinnaird Lindsay, and Williamson Toby (2018). “A Seat Around the Table: Participatory Data Analysis With People Living With Dementia.” Qualitative Health Research 28(9): 1421–1433.\ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whittle HJ, Palar K, Hufstedler LL, Seligman HK, Frongillo EA, Weiser SD. Food insecurity, chronic illness, and gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area: An example of structural violence in United States public policy.Soc Sci Med. 2015. Oct; 143():154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weininger EB and Lareau A.Translating Bourdieu into the American context: the question of social class and family-school relations Poetics (Amsterdam), 2003, Volume 31, Issue 5–6 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farmer Paul E., Nizeye Bruce, and Keshavjee Salmaan (2006). “Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine.” PloS Medicine 3(1): 686–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanna B, Farmer P, Kleinman A, Kim JY and Basilico M (2013). Unpacking Global Health: Theory and Critique. In Reimagining Global Health: An Introduction. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez Andrea M., Bourgois Philippe, Wenger Lynn D., Lorvick Jennifer, Martinez Alexis N., and Kral Alex H. (2013). “Interdisciplinary Mixed Methods Research with Structurally Vulnerable Populations: Case Studies of Injection Drug Users in San Francisco.” International Journal of Drug Policy 24(2): 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]