Abstract

The broad isolation, separation, and loss resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic raise risks for couples' relationship quality and stability. Guided by the vulnerability–stress–adaptation model, we suggest that how pandemic-related loss, isolation, and separation impact couples' relationships will vary depending on the amount and severity of pandemic-related stress, together with enduring personal vulnerabilities (e.g. attachment insecurity), both of which can disrupt adaptive dyadic responses to these challenges. A review of emerging research examining relationship functioning before and during the initial stages of the pandemic offers support for this framework. We draw on additional research to suggest pathways for mitigating relationship disruptions and promoting resilience.

Keywords: Stress and coping, COVID-19 pandemic, Close relationships, Attachment, Support

The COVID-19 pandemic, as with all major shared community events and disasters, raises risks for broad isolation, separation, and loss. Pandemic restrictions have produced separation from important others (family, friends, coworkers) and support networks (childcare, health care) along with myriad losses (financial, employment, health, time, space) that challenge health and well-being. Stressful contexts involving these challenges can jeopardize couples' relationship quality and stability and family functioning [1, 2, ∗∗3]. We apply the vulnerability–stress–adaptation (VSA) model [4] to consider how pandemic-related loss, isolation, and separation may impact couples' relationships [5], depending on the level and type of pandemic-related stress encountered [6,7] along with enduring personal vulnerabilities (e.g. attachment insecurity) that disrupt adaptive responses to these challenges. Emerging research examining relationship functioning before and during the initial stages of the pandemic provides support for this framework, as well as identifies pathways for resilience.

The vulnerability-stress-adaption (VSA) model applied to the COVID-19 pandemic

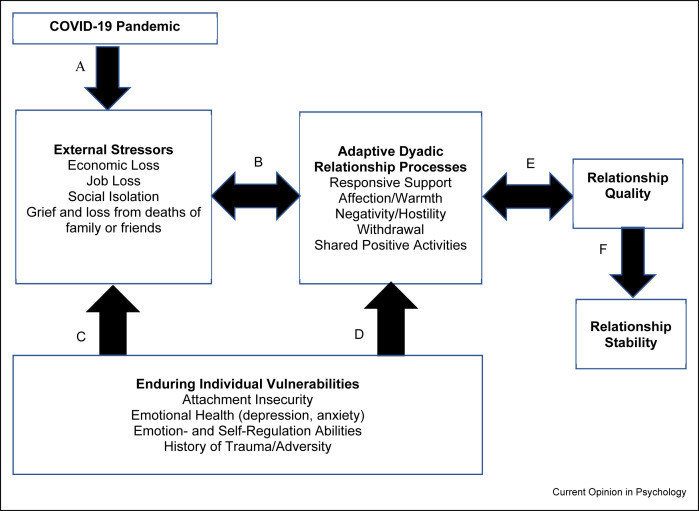

Figure 1 illustrates the VSA model, adapted to focus on stress from loss, separation, and isolation associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (for a related framework focusing on loss-related disasters/crises, see [8]). The model suggests that the pandemic will give rise to multiple stressors evoking feelings of loss, separation, and isolation (path A), that in themselves (path B) and together with couple members' pre-existing vulnerabilities (e.g. attachment insecurity; paths C and D), will mold couples' adaptive dyadic processes, including how they communicate, problem-solve, and support each other, which, in turn, will impact relationship quality and stability (paths E and F).

Figure 1.

How the COVID-19 pandemic may shape relationship processes and outcomes. The framework (adapted from Karney and Bradbury, 1995) suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic will create a variety of external stressors involving loss and social isolation that may interfere with adaptive dyadic relationship processes, which, in turn, can intensify the impact of external stressors as well as lower relationship quality and threaten relationship stability. Couples in which one or both members have enduring vulnerabilities (e.g. attachment insecurity, depression) will be more likely to experience greater negative and fewer positive interactions, and the impact of external stressors may be heightened. The figure was adapted from “Applying Relationship Science to Evaluate How the COVID-19 Pandemic May Impact Couples' Relationships” by P. R. Pietromonaco and N. C. Overall, 2021, American Psychologist, 76 (3), p. 440 (https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000714), Copyright 2021 by the American Psychological Association.

Loss, separation, and isolation and relationship outcomes (paths B, E, and F)

Numerous studies before the COVID-19 pandemic document that people faced with stress from outside the relationship—such as financial or job stress—are more likely to interact with their partner in ways that damage relationship quality across time, such as being overly critical, blaming, or being unresponsive to their partners [1,9, ∗10, 11]. A key reason that stress undermines adaptive dyadic processes is by taxing individuals' capacity to enact the effort and attention required to constructively engage with their partner [2,12]. Elevated stress also can interfere with perceiving the partner's need for support and therefore whether people provide effective support [13].

The COVID-19 pandemic is accompanied by multiple stressors, including social distancing, confinement at home while coordinating increased demands to balance daily tasks (e.g. job/career, childcare), and the lack of control, irritation, and frustration produced by disruptions and losses across many domains (e.g. economic, relational). These multiple stressors are embedded in a context in which people view family as more important, and conflict as more likely, during the pandemic than before [14]. In addition, disruptions from the pandemic make it more challenging than usual for couple members to balance maintaining their independence while also preserving closeness and connection with their partner [15]. The situation therefore is ripe for overloading individuals' cognitive and emotional resources, thereby undermining their ability to respond effectively when relationship problems arise as well as detect and provide support when partners need to rely on each other.

To evaluate whether pandemic-related stress adversely affects relationships, we summarize findings from the few studies assessing relationship functioning both before and during the pandemic, allowing for clearer tests of this link. Findings from the German Family Panel study indicated that both men and women (N = 781 individuals) in marital/cohabiting relationships declined in relationship satisfaction from before to during the pandemic, regardless of pandemic-related employment changes [16]. Another study of 157 couples who were confined in mandatory quarantine with their children found that greater quarantine-related stress predicted residual decreases in relationship functioning (increased relationship problem severity, decreased problem-solving efficacy) and family functioning (increased home chaos, decreased family cohesion) [7], as well as residual increases in harsh parenting among those who perceived low (but not high) partner support [17].

Difficulty equitably managing the increased housework and parenting demands of quarantine also predicted greater relationship problems and dissatisfaction [6]. Finally, parents (N = 365) who experienced greater stress in mandatory quarantine also reported increases in verbal aggression toward their intimate partners [18].

However, the pandemic may offer opportunities to strengthen relationships by allowing couples to band together against external threats [5]. This possibility may be why a study assessing 654 individuals in marital, cohabiting, or dating relationships before and during the early months of the pandemic found no differences in either relationship satisfaction or blaming their partner for mishaps regardless of the negativity of pandemic experiences [19]. Furthermore, those who reported that they and their partners were coping well, or had low relationship conflict, evidenced increased relationship satisfaction and decreased partner blaming. Although these improvements were small, they suggest that engaging in adaptive dyadic processes during this stressful context may benefit relationships. Indeed, counter to early predictions of a surge in divorces, United States' divorce rates in Florida, Missouri, New Hampshire, and Oregon were lower in March–May 2020 than those in March–May 2018 and 2019 [20].

Yet, the degree to which couples remain resilient, sustain positive relationship functioning, and stay together is likely to vary by additional factors. For example, couples with children have faced additional demands, including equitably balancing increased work and childcare demands, and thus likely experienced greater stress [21], more depleted resources required to be responsive, and less time to foster relationship connection. These differences may be why studies examining married couples with children illustrated more detrimental outcomes [7,16,18]. Similarly, the number and severity of stressors will likely be greater for couples entering the pandemic with greater economic or social challenges, and the impact of such ongoing stress and isolation likely grew after the early pandemic months assessed in the studies mentioned above. Finally, the VSA model [4] and our application to the COVID-19 pandemic [5] suggest that how much pandemic-related stress damages relationships will depend on pre-existing vulnerabilities.

Enduring individual vulnerabilities (paths C and D)

Individuals enter stressful situations including the pandemic with pre-existing personal vulnerabilities that shape their perceptions of stress and dyadic processes and also can spillover to impact their partner's perceptions and dyadic processes. Enduring vulnerabilities can include attachment insecurity [22,23], depression [24], emotion regulation strategies [25], and neuroticism [26] that interfere with adaptive dyadic exchanges (e.g. effective communication, being supportive) and in turn threaten relationship well-being. Furthermore, recent work demonstrates that individual vulnerabilities, such as poor emotion regulation strategies (expressive suppression, rumination) and neuroticism, can exacerbate adverse psychological and physical responses during the pandemic [26,27]. Moreover, enduring vulnerabilities will have the greatest impact when people encounter more pandemic-related stress, as illustrated by research assessing relationship functioning before and during the pandemic.

Attachment insecurity is relevant because the pandemic raises threats, such as fears about mortality, uncertainty about the future, and separation from broader social networks, that can activate attachment concerns and lead individuals to seek security/comfort using destructive attachment-related affect regulation strategies [23,28]. For example, individuals who are anxiously attached show heightened distress in response to threat and often try to cope by seeking excessive reassurance from their partner. These strategies can create relationship problems for individuals and their partners, including destructive communication patterns, ineffective support provision, and feeling undervalued by the partner [29,30]. Consistent with a diathesis–stress approach to attachment [28], individuals with greater attachment anxiety (assessed pre-pandemic) evidenced increased relationship problem severity during a COVID-19 quarantine, but only if they also experienced high quarantine-related stress [7]. Moreover, individuals with more anxiously attached partners, and thus who likely encountered destructive communication and excessive reassurance seeking from their partner, also showed declines in relationship satisfaction and commitment, increased relationship problem severity, and poorer family cohesion when they experienced high quarantine-related stress.

Individuals who are avoidantly attached tend to disengage when threatened and distance themselves from their partner. Avoidant strategies also interfere with adaptive relationship functioning for individuals and their partners by constraining intimacy and responsive support and leading to ineffective (e.g. withdrawal) and damaging (e.g. hostility) responses to conflict [31, 32, 33]. Accordingly, in the study described previously, individuals with more avoidantly attached partners (assessed pre-pandemic) showed declines in problem-solving efficacy and family cohesion, regardless of their stress, probably because their partner's typical disengagement strategies interfered with resolving conflicts and maintaining closeness. These findings highlight the dyadic nature of couples' relationships: Relationship outcomes are linked not only to individuals' own vulnerabilities but also to their partner's vulnerabilities.

Other pre-existing vulnerabilities involve broader societal attitudes that shape how intimate partners manage power dynamics. For example, men's hostile sexism incorporates beliefs that men, and not women, should possess social power and authority within the family [34]. Men's hostile sexism represents a risk for aggression in couples' relationships, particularly when men feel they lack control or power [35], which is likely during quarantines when couples are confined at home, and must rely on each other isolated from other means to alleviate pandemic-related uncertainty and loss. A recent investigation revealed that men higher in pre-pandemic hostile sexism were more aggressive toward their partners during a mandated quarantine, particularly when they felt less power when interacting with their partner [18].

A host of other personal vulnerabilities (e.g. depression, poor emotion regulation, childhood adversity) will likely shape how couples adapt throughout the pandemic. Individuals with depression, for example, focus on negative aspects of their situation [36,37], which can exacerbate the effects of pandemic-related stressors (path C). Similarly, the overly negative perceptions, hostility, and defensiveness of individuals experiencing depression can undermine adaptive interactions with their partner [38, 39, ∗40], which, in turn, may amplify the effects of pandemic-related stress (path B). Future work comparing couples before and throughout the pandemic is needed to reveal how depression and other vulnerabilities will impact relationships across this time of crisis.

Variation across couples: mitigating relationship disruptions and facilitating resilience

Just as research examining people's responses to loss and trauma reveals considerable variation in psychological responses [41], couples likely will vary in how pandemic-related stress affects long-term relationship distress [5], ranging from trajectories of chronic, prolonged distress to stable resilience. As summarized in Figure 1, and supported by the research reviewed previously, these trajectories will likely depend on the severity of pandemic-related stressors, personal vulnerabilities, and how well couples adapt. These factors also provide insight into how to mitigate relationship disruptions and facilitate resilience.

Couples who experience little economic loss, minimize isolation such as by using technology to connect with others, and have fewer personal vulnerabilities are most likely to show resilience, especially if they communicate effectively and support each other. For these couples, the pandemic and associated lockdowns may yield benefits by creating opportunities to spend more time together in enjoyable or novel activities, which promote relationship growth [42,43]. Moreover, by facing a shared stressor effectively together, they may exit the pandemic with a new appreciation for their relationship. This possibility aligns with recent findings that individuals with moderate exposure to a natural disaster (Hurricane Sandy) reported increased social support, less distress, and less attachment avoidance from before to after the disaster [44].

Most couples are likely to face more challenges, and their trajectories will depend on their ability to sustain adaptive relationship processes throughout the crisis. Just as vaccines inoculate people against the virus, many couples may inoculate their relationships from pandemic-related stressors by engaging in practices that support successful relationships [5,45]. These practices involve effective communication, including refraining from hostility, criticism, and aggression even when negativity occurs, directly working to problem-solve as a team, and being motivated to improve the situation and open to compromise [46, 47, 48]. Safeguarding relationships also involves providing responsive support, including being understanding and attending to partners' concerns [49], which can buffer the adverse effects of stress, or personal vulnerabilities, on relationship well-being [40]. Traversing the pandemic using effective communication and responsive support may mean that, despite short-term increases in distress, many couples recover quickly and emerge with a stronger defense against future challenges.

Couple members who belong to groups with disproportionately greater risks for pandemic-related stress, loss, and isolation (racial/ethnic minorities, parents) may have the most difficulty adapting to challenges from the crisis [5] and incur greater risk for relationship distress and dissolution. Moreover, adaptive dyadic processes (effective communication, responsive support) may not be enough to mitigate intractable problems caused by severe adversity and economic hardship, especially if the pandemic exacerbates these broader contextual stressors [5,8]. For couples most at risk from the pandemic, social policies are needed that provide economic support, jobs/job training, child care, and health care [50], establishing a foundation for couples to benefit additionally from adaptive relationship processes.

Conclusions

The loss, isolation, and separation accompanying the COVID-19 pandemic represent significant challenges for couples' relationships, interfering with adaptive relationship processes (e.g. increasing hostility, withdrawal) and risking relationship distress. Couples' relationship trajectories—from chronic distress to stable resilience—will vary depending on their pandemic-related losses, isolation, and separation, personal vulnerabilities, and ability to enact adaptive relationship processes that help to inoculate relationships from pandemic-related stress.

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

This review comes from a themed issue on Separation, Social Isolation, and Loss (2022)

Edited by Gery C. Karantzas and Jeffry A. Simpson

References

- 1.Neff L.A., Karney B.R. How does context affect intimate relationships? Linking external stress and cognitive processes within marriage. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30:134–148. doi: 10.1177/0146167203255984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neff L.A., Karney B.R. Acknowledging the elephant in the room: how stressful environmental contexts shape relationship dynamics. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime H., Wade M., Browne D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2020;75:631–643. doi: 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article provides a comprehensive, broad analysis of how the COVID-19 pandemic may influence both risk and resilience in families and includes implications for practice, policy and research.

- 4.Karney B.R., Bradbury T.N. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: a review of theory, methods, and research. Psychol Bull. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco P.R., Overall N.C. Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples' relationships. Am Psychol. 2021;76:438–450. doi: 10.1037/amp0000714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article offers a comprehensive description of the application of the VSA model to couples' relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic, a detailed discussion of research supporting the theoretical framework, and recommendations for mitigating relationship risks and leveraging opportunities for growth.

- Waddell N., Overall N.C., Chang V.T., Hammond M.D. Gendered division of labor during a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown: implications for relationship problems and satisfaction. J Soc Per Relat. 2021;38:1759–1781. doi: 10.1177/0265407521996476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; This recent study compared couples with children before the COVID-19 pandemic and during a lockdown and highlights the detrimental effects of women's unfair share of parenting and housework on women's relationship quality.

- Overall N.C., Chang V.T., Pietromonaco P.R., Low R.S.T., Henderson A.M.E. Partners' attachment insecurity and stress predict poorer relationship functioning during COVID-19 quarantines. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1177/1948550621992973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; This recent study of couples with children demonstrates the importance of individuals' own and their partner's attachment insecurity in impacting change in relationship quality and family functioning from before the pandemic to during a COVID-19 lockdown.

- 8.Karantzas G.C., Feeney J.A., Agnew C.R., Christensen A., Cutrona C.E., Doss B., Eckhardt C.I., Russell D.W., Simpson J.A. Dealing with loss in the face of disasters and crises: integrating interpersonal theories of couple adaptation and functioning. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022:43. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neff L.A., Karney B.R. Stress and reactivity to daily relationship experiences: how stress hinders adaptive processes in marriage. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97:435–450. doi: 10.1037/a0015663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.P., Karney B.R., Bradbury T.N. When poor communication does and does not matter: the moderating role of stress. J Fam Psychol. 2020;34:676–686. doi: 10.1037/fam0000643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This longitudinal study of a large sample of newlywed couples that demonstrates that, when newlywed spouses experienced greater external stress, declines in the quality of problem-solving predicted declines in relationship satisfaction.

- 11.Williamson H.C., Karney B.R., Bradbury T.N. Financial strain and stressful events predict newlyweds' negative communication independent of relationship satisfaction. J Fam Psychol. 2013;27:65–75. doi: 10.1037/a0031104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck A.A., Neff L.A. Stress spillover in early marriage: the role of self-regulatory depletion. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26:698–708. doi: 10.1037/a0029260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rafaeli E., Gleason M.E.J. Skilled support within intimate relationships. J Fam Theor Rev. 2009;1:20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Funder D.C., Lee D.I., Baranski E., Baranski G.G. The experience of situations before and during a COVID-19 shelter-at-home period. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1177/1948550620985388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates a shift in how people perceive their situational experiences before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, with perceptions during the pandemic shifting to emphasize both importance of family and the greater potential for conflict.

- 15.Feeney J.A., Fitzgerald J. Loss of connection in romantic relationships. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;43 [Google Scholar]

- Schmid L., Wörn J., Hank K., Sawatzki B., Walper S. Changes in employment and relationship satisfaction in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the German family Panel. Eur Soc. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]; This large longitudinal study of individuals in relationships reveals a decrease in relationship satisfaction from before the COVID-19 pandemic to during the early months of the crisis.

- 17.McRae C.S., Overall N.C., Low R.S.T., Chang V.T. Parents' distress and poor parenting during COVID-19: the buffering effects of partner support and cooperative coparenting. Dev Psychol. 2021 doi: 10.1037/dev0001207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall N.C., Chang V.T., Cross E.J., Low R.S.T., Henderson A.M.E. Sexist attitudes predict family-based aggression during a COVID-19 lockdown. J Fam Psychol. 2021 doi: 10.1037/fam0000834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; These recent findings show that men higher in hostile sexism prior to the pandemic were more likely to show an increase in aggressive behavior toward their intimate partners and children during a COVID-19 lockdown.

- Williamson H.C. Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on relationship satisfaction and attributions. Psychol Sci. 2020;31:1479–1487. doi: 10.1177/0956797620972688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This longitudinal, national study demonstrates that individuals showed no change in relationship satisfaction from pre-pandemic to the early months of the pandemic, and they became less likely to blame their partners for negative behavior.

- 20.Manning W.D., Payne K.K. Bowling Green State University; 2020. Marriage and divorce decline during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study of five states. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge J.M., Joiner T.E. Mental distress among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76:2170–2182. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work provides context for why the impact of personal vulnerabilities such as depression on relationship functioning are particularly important over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 22.Pietromonaco P.R., Beck L.A. In: Mikulincer M., Shaver P.R., Simpson J.A., Dovidio J.F., Mikulincer M., Shaver P.R., Simpson J.A., Dovidio J.F., editors. vol. 3. American Psychological Association; 2015. Attachment processes in adult romantic relationships; pp. 33–64. (APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Interpersonal relations). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikulincer M., Shaver P.R. Guilford Press; 2007. Attachment in adulthood: structure, dynamics, and change. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davila J., Bradbury T.N., Cohan C.L., Tochluk S. Marital functioning and depressive symptoms: evidence for a stress generation model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:849–861. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low R.S.T., Overall N.C., Cross E.J., Henderson A.M.E. Emotion regulation, conflict resolution, and spillover on subsequent family functioning. Emotion. 2019;19:1162–1182. doi: 10.1037/emo0000519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroencke L., Geukes K., Utesch T., Kuper N. Back MD: neuroticism and emotional risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Res Pers. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study examining daily experiences over the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that an enduring personal vulnerability, neuroticism, is associated with greater preoccupation with information about COVID-19, which in turn, predicted greater negative affect.

- Low R.S.T., Overall N.C., Chang V.T., Henderson A.M.E. 2020. Emotion regulation and psychological and physical health during a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study indicates that emotional suppression and rumination (personal vulnerabilities) predicted poorer psychological and social functioning, and rumination predicted poorer physical health, during lockdown, controlling for pre-pandemic psychological and social functioning, or physical health.

- 28.Simpson J.A., Rholes W.S. Adult attachment, stress, and romantic relationships. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Overall N.C., Girme Y.U., EPJr Lemay, Hammond M.D. Attachment anxiety and reactions to relationship threat: the benefits and costs of inducing guilt in romantic partners. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:235–256. doi: 10.1037/a0034371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayamaha S.D., Girme Y.U., Overall N.C. When attachment anxiety impedes support provision: the role of feeling unvalued and unappreciated. J Fam Psychol. 2017;31:181–191. doi: 10.1037/fam0000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck L.A., Pietromonaco P.R., DeVito C.C., Powers S.I., Boyle A.M. Congruence between spouses' perceptions and observers' ratings of responsiveness: the role of attachment avoidance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014;40:164–174. doi: 10.1177/0146167213507779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Overall N.C., Simpson J.A., Struthers H. Buffering attachment-related avoidance: softening emotional and behavioral defenses during conflict discussions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104:854–871. doi: 10.1037/a0031798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overall N.C., Fletcher G.J.O., Simpson J.A., Fillo J. Attachment insecurity, biased perceptions of romantic partners' negative emotions, and hostile relationship behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108:730–749. doi: 10.1037/a0038987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glick P., Fiske S.T. The ambivalent sexism inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cross E.J., Overall N.C., Low R.S.T., McNulty J.K. An interdependence account of sexism and power: men's hostile sexism, biased perceptions of low power, and relationship aggression. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2018 doi: 10.1037/pspi0000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon A.M., Tuskeviciute R., Chen S. A multimethod investigation of depressive symptoms, perceived understanding, and relationship quality. Pers Relat. 2013;20:635–654. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Overall N.C., Hammond M.D. Biased and accurate: depressive symptoms and daily perceptions within intimate relationships. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2013;39:636–650. doi: 10.1177/0146167213480188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barry R.A., Barden E.P., Dubac C. Pulling away: links among disengaged couple communication, relationship distress, and depressive symptoms. J Fam Psychol. 2019;33:280–293. doi: 10.1037/fam0000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knobloch-Fedders L.M., Knobloch L.K., Durbin C.E., Rosen A., Critchfield K.L. Comparing the interpersonal behavior of distressed couples with and without depression. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:1250–1268. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco P.R., Overall N.C., Powers S.I. Depressive symptoms, external stress, and marital adjustment: the buffering effect of partner's responsive behavior. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1177/19485506211001687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This longitudinal study demonstrates that newlywed spouses with either a personal vulnerability (depression), or greater external stress, are buffered from the detrimental effects of these factors on relationship quality over time if their partner shows highly responsive behavior during laboratory interactions about areas of conflict.

- 41.Bonanno G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Girme Y.U., Overall N.C., Faingataa S. “Date nights” take two: the maintenance function of shared relationship activities. Pers Relat. 2014;21:125–149. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gable S.L., Gonzaga G.C., Strachman A. Will you be there for me when things go right? Supportive responses to positive event disclosures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91:904–917. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini A.D., Westphal M., Griffin P. Outside the eye of the storm: can moderate hurricane exposure improve social, psychological, and attachment functioning? Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2021 doi: 10.1177/0146167221990488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This longitudinal study highlights that moderate exposure to a natural disaster may yield some social, psychological, and relational benefits.

- 45.Neff L.A., Broady E.F. Stress resilience in early marriage: can practice make perfect? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101:1050–1067. doi: 10.1037/a0023809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Overall N.C. Does partners' negative-direct communication during conflict help sustain perceived commitment and relationship quality across time? Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2018;9:481–492. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Overall N.C., McNulty J.K. What type of communication during conflict is beneficial for intimate relationships? Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Overall N.C. Behavioral variability reduces the harmful longitudinal effects of partners' negative-direct behavior on relationship problems. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1037/pspi0000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pietromonaco P.R., Collins N.L. Interpersonal mechanisms linking close relationships to health. Am Psychol. 2017;72:531–542. doi: 10.1037/amp0000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karney B.R., Bradbury T.N., Lavner J.A. Supporting healthy relationships in low-income couples: lessons learned and policy implications. Pol Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2018;5:33–39. [Google Scholar]