Abstract

Digital technology and social media platforms have transformed the ways adolescents communicate and cultivate romantic relationships, but few studies consider whether relationships initiated online are less salutary than those formed in person. A sample of 531 adolescents (Mean age = 16.7 years, SD=0.358; 55% female) was recruited from an ongoing birth cohort study and administered bi-weekly diaries over a year to evaluate the circumstances associated with adolescents’ romantic relationship formation and relationship quality. Two-thirds of respondents initiated one or more romantic relationships during the study, of which 15% were initiated online. Girls who did not fit in well at school and who had difficulty making friends were more likely to initiate romantic relationships online than their more sociable peers who fit in well at school; for boys, however, access to mobile devices increased the odds that romantic relationships were initiated online. The diaries captured considerable flux in the evolution of romantic relationships, but there was limited evidence that relationships initiated online involved greater risks, with the notable exception of greater age asymmetry.

Keywords: adolescent romantic relationships, online partner search, relationship quality, diary study, gender differences

Introduction

Digital technology and social media platforms altered both the ways and the social contexts within which adolescents communicate and initiate romantic relationships (Lenhart et al., 2015). A recent national study of adolescents ages 13 to 17 reported that about one-in-four teens who ever dated met a current or previous partner online, and that half of those who initiated romantic relationships online met multiple romantic partners virtually (Lenhart et al., 2015). The report stopped short of addressing what circumstances are associated with adolescents’ search for romantic partners online or whether relationships initiated virtually are less salutary than those formed in person, as several studies suggest (e.g., Buhi et al., 2012). Both questions are addressed in the current study, which uses diary methods that are well suited to capture flux in teens’ romantic relationships (Goldberg et al., 2019a).

Adolescent Romance in the Digital Age

A large body of scholarship has documented the developmental significance of adolescent romantic relationships, demonstrating associations with several outcomes ranging from emotional wellbeing to educational aspirations and the capacity to form healthy adult partnerships (Giordano, 2003). There is also ample evidence that the socio-emotional consequences of adolescent romance depend both on the quality of the partnership and the social contexts in which relationships develop (Collins et al., 2009). The major longitudinal studies that have been used to investigate the developmental significance of adolescent romance, such as the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (ADD Health) and The Toledo Adolescent Relationship Study (TARS), were conducted well before the expansion of social media platforms used by teens to cultivate and maintain social relationships (Anderson and Jiang, 2018). Among studies that examined adolescents’ use of digital technology in their current and former romantic relationships, only a handful systematically considered how romantic relationships initiated online differ from those initiated in-person (Blunt-Vinti et al., 2016).

Paralleling studies of teen romance in the pre-digital age, the growing body of empirical research about adolescents’ use of social media in romantic relationships takes a problem-centered approach, focusing on risks that include personal disclosures (Pujazon-Zazik et al., 2012), sexting (Ahern and Mechling, 2013), health risks (Buhi et al., 2012), verbal abuse (Reed et al., 2020) and inter-partner conflict (Todorov et al. 2021). Nevertheless, a nationally representative cross-sectional study showed relatively low prevalence of offensive and controlling behavior, with most negative experiences arising after a break-up (Lenhart et al., 2015). Over-reliance on cross-sectional designs misses short relationships and distorts the dynamism of teen’s use of digital technology to initiate and cultivate romantic relationships (Rizzo et al., 2019).

In contrast to problem-focused approaches, several studies claimed that access to social media and digital technology is a positive development that, in addition to enabling youth to broaden and deepen friendships, including transitions to romantic relationships, also allows socially awkward teens to overcome difficulties in self-presentation (Pitman and Reich, 2016). In fact, rather than promote risky behavior, some scholars argued that access to smartphones largely accentuates offline vulnerabilities (Odgers, 2018). Furthermore, the Internet can potentially broaden dating pools beyond physical spaces while also providing some protection against peer scrutiny. Online partner search may be particularly important for teens who are exploring their sexual identity. For example, one study found not only that socially awkward teens compensated for weak social skills by searching for partners online more frequently than their better-adjusted peers, but also that LGBTQ teens were over five times more likely than their heterosexual peers to have met a romantic partner online (Korchmaros et al., 2015). Among adults, partnerships formed online were observed to be comparable in quality to those formed in-person even after considering potential dissolution biases (Rosenfeld and Thomas, 2012), but whether similar findings obtain for teenagers is unclear. For adolescents, evidence on the quality of relationships initiated virtually also is limited. One study reported higher satisfaction with sexual partners met in person compared with those met online (Blunt-Vinti et al. (2016), but these findings were based on a convenience sample of teens seeking clinical services and hence of uncertain external validity.

Social Contexts of Adolescent Romance *

Attachment theory, the dominant theoretical framework invoked to understand the correlates and consequences of adolescent romantic relationships, hypothesized an association between secure emotional bonding early in life, particularly with parents and primary caregivers, and the capacity to form emotional attachments later in life (Freeman and Brown, 2001). Later formulations acknowledged that lived experiences, expanded peer networks, and family dynamics modify early attachment systems in ways that that either strengthen or weaken adolescents’ capacity to form intimate bonds (Allen, 2008). Therefore, an understanding of adolescent romantic relationships requires considering overlapping influences of parents and peers that accumulate over the early life course (Roisman et al., 2008).

Understanding about adolescent romantic relationships has been limited by inconsistent terminology across studies and research designs with insufficient measurement precision to capture short relationships (Karney et al., 2007). Varying definitions have resulted in discrepant estimates of the prevalence, longevity, and evolution of adolescent romantic relationships. Unlike dissolutions, which often are event triggered, the initial stages of teen romantic relationships often are ambiguous, especially if partners were friends before becoming romantically involved, and may not involve partner exclusivity (Meier and Allen, 2009). Although most studies recognized established and reciprocated relationships and some acknowledged sexual “hook-ups,” relatively few studies asked about “flirting/and talking,” which not only is part of the screening process for romantic relationships, but also the essential first step to connect virtually with prospective partners (Baker and Carreño, 2016). Lack of prospective measurement precision also has hampered understanding of how and where adolescent relationships emerge.

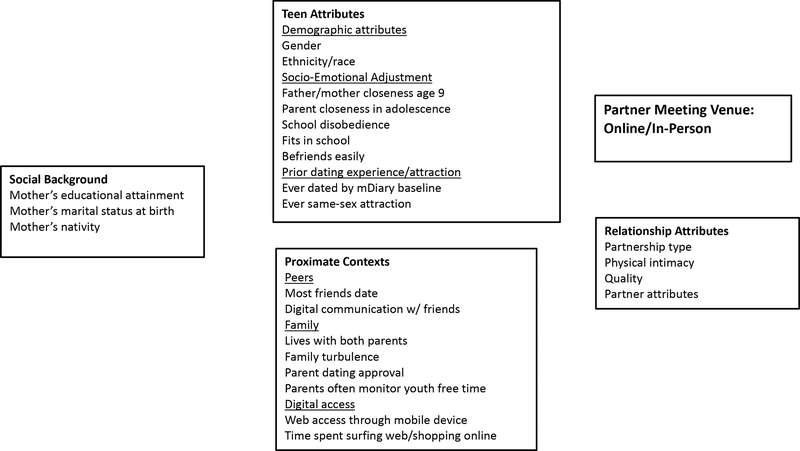

Figure 1, which is adapted from Karney et al. (2007, Figure S1) and Goldberg and Tienda (2017, Figure 1), presents a framework to understand adolescents’ propensity to initiate romantic relationships in-person versus online. Indicators of socio-emotional attachment include measures of parent-child closeness at two stages in the life course as proxies for attachment security (Venta et al., 2014; River et al., 2021), as well as measures of school fit and awkwardness (George et al., 2018). Whether teens with weak parent bonds are more prone to search for romantic partners online may depend on family structure and stability (Goldberg et al., 2017); whether and how parents supervise online activities (Anderson, 2016); and how much control parents exercise over dating (Jorgensen-Wells, et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Social Contexts of Teen Romantic Relationships

Evidence about whether and how parents regulate adolescents’ online behavior is inconsistent because of differences in parents’ and teens’ reports about whether monitoring occurs (Anderson, 2016); because of socioeconomic variation in teens and parents’ digital proficiency (Rideout and Robb, 2019); and because the proliferation of mobile devices complicates parents’ ability to monitor online behavior even when they attempt to do so (Özgür, 2016). Prior studies found that having supportive, involved parents and stable family environments protects teens against risky behavior offline and online (Wang et al., 2005). For example, close and supportive parent-child relationships have been linked with delayed sexual onset and higher quality adolescent romantic relationships (Longmore et al., 2009). Other scholarship showed that teens whose parents enjoy stable, high-quality relationships delay sexual debut (Goldberg et al., 2017) and experience higher partnership quality and lower rates of intimate partner violence themselves (Tschann et al., 2008).

During adolescence, peer networks become a key developmental context within which romantic relationships emerge (Allen, 2008); however, more than its size, composition of the peer group has been associated with adolescents’ propensity to form romantic relationships (King and Harris, 2007). Peers with dating experience provide valuable information about romantic experiences (Flynn et al., 2017), but it is unclear whether teens whose friends are romantically experienced will be more inclined to search for romantic partners online. Most adolescent peer networks are forged in school settings, where teens learn how to manage fear of rejection as they navigate status cultures (Jorgensen -Wells et al., 2021), but for socially awkward youth with small friendship networks, online social media platforms may help compensate for weak social skills while potentially broadening dating pools. One implication is that youth who have difficulty making friends and fitting in will be more inclined to search for romantic partners online.

In addition to embeddedness in networks of dating peers, extensive use of digital technology to communicate with friends is expected to boost the likelihood of initiating a romantic relationship online (Lenhart et al., 2015). Despite the proliferation of digital technology, however, not all adolescents have access to mobile devices (Anderson, 2015). Access to digital technology is a necessary but insufficient condition to initiate romantic relationships online, which also depends on the amount of time spent surfing the Internet and offline socio-emotional adjustment (Rideout and Robb, 2019).

Gender Differences in Romantic Relationships

Many studies reported gender differences in experiences with romantic relationships, but findings are inconsistent (Meier and Allen, 2009). For example, some evidence showed that adolescent girls were more oriented toward intimacy and commitment than boys (e.g., Carver et al., 2003), but other scholarship found no gender differences in relationship emotionality (Giordano et al., 2006). Gender differences in social media use also are mixed, with some evidence that adolescent girls used social media to monitor a partner while boys used social media to build relationships (Reed et al., 2016), another showing that adolescent girls more than boys engaged in compulsive texting (Coyne et al., 2017), and mixed evidence on gender differences in digital dating abuse (Reed et al., 2017).

Gender differences in adverse and salutary outcomes of adolescent romantic relationships are also inconsistent across studies. For example, some studies identified a stronger association between adolescent romantic experiences and poor emotional health among girls (Joyner and Udry, 2000; Soller, 2014), whereas other research using intensive longitudinal data found little evidence of gender variation (Rogers et al., 2018). Evidence about whether and how gender may moderate associations between partner meeting venues and other correlates of adolescent development is scant.

Current Study

Most studies about teens’ online communication with current, past, and prospective romantic partners are based on cross-sectional designs or longitudinal studies with long inter-wave intervals, which potentially miss short partnerships that are common during adolescence and incur recall biases. Furthermore, few studies about adolescents’ use of digital media in their romantic relationships considered meeting venues in assessments of risks and relationship quality, therefore it is unclear whether and how relationships initiated online versus in-person are consequential for partnership quality. Using data from a digital diary study designed to track the initiation and evolution of adolescents’ romantic relationships over a year, the current study describes how romantic relationships initiated online differ from those formed in person, identifies childhood precursors and proximate social contexts associated with teens’ romantic partnering behavior, and evaluates whether relationships initiated online pose greater risks than those formed in person. Diary methods permit identification of relationship beginnings and evolution in real time, which is an important consideration for short-lived relationships, while minimizing recall biases that plague cross-section methods.

Methods

Data

The empirical analyses are based on data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) and the mDiary Study of Adolescent Relationships (mDiary). FFCWS is a prospective birth-cohort study that followed almost 5,000 children born at the turn of the millennium in 20 medium-to-large U.S. cities (Reichman et al., 2001). The FFCWS, which oversampled births to unmarried mothers, interviewed mothers or primary caregivers (PCGs) six times by the time target youth reached age 15. Target youth were interviewed at ages 9 and 15. The FFCWS surveys provide rich background information about target teens’ socioeconomic background, childhood living arrangements, school behavior, psychosocial wellbeing, and parenting behaviors. The mDiary was designed to track the emergence and evolution of adolescent romantic and sexual relationships by administering an intensive longitudinal survey bi-weekly over 52 weeks to a subset of FFCWS youth residing in 15 of 20 FFCWS cities. In eleven of the fifteen target cities, mDiary sampled 100% of eligible adolescents and in the remainder randomly sampled at a rate of 44%. FFCWS Year-15 respondents with invalid contact information were excluded from the mDiary sampling frame.

Recruitment for the mDiary study, which occurred over a 16-month period on a rolling basis, lagged the ongoing Year-15 field operations of the FFCWS parent study by approximately one year. There were two eligibility requirements for youth to participate in the mDiary study: (1) completion of the FFCWS Year-15 interview and (2) access to a personal email address. The email address was needed to ensure reliable access to registration information and to receive survey reminders. Of the 1,343 teens who met the eligibility criteria, 689 assented to participate in the mDiary study. Registration on the mDiary web portal required teens to complete a short enrollment survey designed to gauge changes in personal and family circumstances in the intervening year between the FFCWS Year-15 interview and the mDiary study.

Over three-fourths of assented teens (531/689) registered for the mDiary study, allowing them to complete the bi-weekly diaries on a device of choice. To incentivize participation, respondents were offered Amazon e-gift cards—$5 for completing the enrollment survey, $2 for each completed diary, and a $10 bonus for competing the last diary. Both the enrollment survey and the bi-weekly diaries were administered via a custom, mobile-optimized website linked to the Qualtrics web survey platform via Application Programming Interface (API) calls. Qualtrics’ panel functionality was used to track new and continuing partnerships across diaries, to record partner attributes, and to customize questions about the nature of specific relationships. All diaries remained open for one week, after which time they were considered skipped.

During the observation period, the 531 mDiary participants completed 9,861 of the 13,806 bi-weekly diaries for which they were eligible for an overall compliance rate of 71%. Response rates for intensive longitudinal studies that used similar protocols with adolescents and lasted a year are unavailable; however, a meta-analysis of 42 studies that used shorter duration ecological momentary assessment protocols with youth ages 18 and under reported average weighted compliance rates between 73% and 78% (Wen et al., 2017).

Measures

Romantic relationships and meeting venues.

The measures used in the analyses are summarized in Figure 1. The primary dependent variable, whether teens reported meeting a romantic partner online or in person, is a binary measure restricted to romantic relationships that occurred during the mDiary study. In all 25 diaries, teens were asked “Is there someone you are currently talking to, flirting with, dating or hooking up with?” This question is particularly suited for identifying relationships initiated online, which perforce begin with “talking and flirting” (Baker and Carreño, 2016). Teens who participated in a focus group discussion as part of the mDiary pilot recommended including “talking and flirting” as a relationship status known to peers.

For each new relationship, respondents were asked to provide the partner’s initials or a nickname, which was used to follow the relationship over time. Several questions were asked about each new partner, including age, race, gender and, importantly, meeting venue: “Where did you and {NAME} first meet?” Response choices included school, neighborhood, summer camp, party, church, internet/social media, friend or relative house, or other location. To be conservative in coding partner meeting venues, respondents who did not report a specific venue were assumed to have met their partner in person.

Additional questions, which were asked on a bi-weekly basis, were designed to characterize the relationship and its evolution over time. For each reported romantic relationship, diaries recorded age heterogamy (over 2-year and over 3-year age differences) and the sex of the partner (same or opposite sex). Diaries also recorded relationship quality (very good, excellent, good, fair, or poor) on a bi-weekly basis. Relationship duration was based on the number of diaries relationships were recorded. Respondents in romantic relationships also were asked about controlling and emotionally or physically abusive behavior toward or from their partner. These items included putting the partner down in front of others, keeping the partner from seeing friends, threatening the partner with violence, or physically abusing the partner (response choices to each item are yes, no, refuse or don’t know). Given the low incidence of abuse, respondents’ abuse perpetration and victimization were combined to index violence within the partnership.

Frequency of in-person contact over the past two weeks was indexed with categories of never, less than once a week, 1 or 2 days a week, 3 or 4 days a week, and every day or almost every day. The bi-weekly diaries also recorded intimate behavior (at first mention of each new partner, and for continuing partnerships, in the past two weeks), with two questions: “Have you and {partner name} done any of the following? Kissed, more than kissing, or none of the above?” Respondents who indicated more than kissing were asked “Have you had sexual intercourse with {partner name}?” Responses to these questions were used to measure whether the relationship involved any non-intercourse sexual activity or sexual intercourse.

Teen attributes.

Because mDiary respondents were sampled from a birth cohort study, there was little age variation (median and mean age = 16.7 years; SD = 0.358), and virtually all were enrolled in school. Respondents’ assigned sex at birth was obtained from the FFCWS baseline survey. Self-identification reported at the Year-15 interview was used to classify teens into four groups: non-Hispanic White, Black, Hispanic, and other, which included Asians and mixed-race respondents.

Teen socio-emotional adjustment.

Venta et al. (2014) used closeness to parents as proxies for attachment security. Both the FFCWS Year 9-child and mDiary enrollment surveys asked respondents how close they felt to their parents or guardians (extremely close, quite close, fairly close, or not close. In the Year-9 interviews, teens were asked separate questions about closeness to mothers and fathers; response choices included a response category indicating that the target youth had no contact with the parent in the prior year. Because virtually all youth in single parent families resided with their mothers, for the measure of maternal closeness at age 9, responses for no contact in the past year were combined with fairly or not very close. The mDiary enrollment survey referred to parents or guardians (“How close do you feel to your parents or guardians?”) and did not include a response category indicating contact in past year. Therefore, and based on the response distributions, a tri-partite measure that combined fairly or not very close was used to measure closeness at age 16: extremely close; quite close, and fairly or not very close.

Both the Year-15 primary caregiver and teen interviews were used to create measures of respondents’ socio-emotional adjustment. These include offline externalizing behavior, which prior studies have linked to early sexual debut (Turney and Goldberg, 2019), and sociability, which has been linked to development of romantic interests (Zimmer-Gembeck, 2002). Parents’ reports about school disobedience (1= often or sometimes true) were used to create an indicator of externalizing behavior. Sociability was assessed by creating categorical measures from the Year-15 teen survey, which asked teens how well they fit in school and how easily they made friends: “I feel like I am part of my school” (strongly agree; somewhat agree; disagree or home schooled); and “I make friends easily” (not true; sometimes true; often true). School fit was operationalized as a tripartite categorical measure and based on the response distribution, ease of making friends was dichotomized (often true = 1).

Prior dating experience and same-sex attraction.

Respondents were asked about their past dating behavior in the mDiary enrollment survey (“Have you ever dated or been in a relationship with someone?”) and about same-sex attractions. Responses about prior dating experience were used to create a binary measure indicating whether respondents themselves had ever dated prior to beginning the diary study (approximately age 16). It was expected that teens with prior dating experience would be more inclined to search for romantic partners online than their inexperienced peers.

Guidelines specified by the Williams Institute (Badgett et al., 2009) were used to capture same-sex attractions. The mDiary enrollment survey asked male and female respondents two separate questions: “Have you ever had a crush on a girl/boy (ever liked a girl/boy) more than just a friend?” Respondents with same-sex attractions were identified by pairing teens’ assigned sex with their responses to the attraction questions (Mittleman, 2019). Specifically, if a girl (boy) reported ever having liked a girl (boy) more than a friend in the enrollment survey, then same-sex attraction = 1.

Proximate Contexts.

The mDiary enrollment survey asked about the partnering behavior of the respondent’s peer group: “Of the friends you spend time with, how many have dated?” Response choices included all or almost all; some; a few or none. Because the response distribution was highly skewed, a binary measure was created to distinguish between respondents who reported that “all or almost all” of their peers dated (= 1) and those indicating otherwise.

Measures of respondents’ access to and use of digital technologies to communicate with friends were derived from the FFCWS Year-15 surveys. Access to a mobile phone, which facilitates online partner search with limited parental oversight (Anderson 2016), was obtained from the Year-15 primary caregiver survey and operationalized as a binary measure (1 = yes). To assess online behavior, the number of daily weekday hours spent surfing the web or shopping online reported in the Year-15 teen interviews were used to construct an interval measure (mean 4.9 hours; SD = 1.5). Information about the number of daily weekday hours spent communicating digitally with friends was derived from the FFCWS Year-15 teen survey (mean = 3.9 hours, SD = 3.4).

Two measures derived from the FFCWS surveys were used to characterize respondents’ family circumstances: teens’ report that they lived with both biological parents at age 15 (=1) and mothers’ reports of their own relationship instability. The latter measure was created by counting mother’s transitions into and out of unions with cohabiting or marital partners between the Year-9 and Year-15 PCG interviews (mean = 0.5, SD = 0.8).

The mDiary enrollment survey was used to operationalize parent support of dating and monitoring behavior using two questions: “How often do your parents keep track of what you do during your free time?” (often; sometimes; rarely; or never), and “Whether or not you have ever dated, would your parents or guardians approve of you dating at this time in your life” (approve; wouldn’t care; or disapprove). Responses to both questions were used to construct binary measures indicating whether teens reported that their parents approved of their dating at this time in life (=1), as opposed to not caring or disapproving (=0), and whether their parents often monitored their activities (=1), versus sometimes, rarely, or never.

Social background.

Several measures were used to portray respondent’s socioeconomic background, including mothers’ schooling (Karney et al., 2007), nativity (King and Harris, 2007), and marital status at birth of the target youth (Goldberg et al., 2017). The baseline FFCWS interviews recorded mother’s educational attainment, which was operationalized as a categorical variable (less than high school; high school or equivalent; some college; college graduate). Indicator measures recorded whether mothers were married to the target child’s father at birth (=1) and mothers’ nativity (foreign = 1).

Analyses

Descriptive and multivariate analyses used a file that merged mDiary enrollment survey and bi-weekly diary data with data from the FFCWS baseline survey, the Year-9 child survey (Year 9-child), and both the Year 15 surveys conducted with primary caregivers (Year 15-PCG) and with target youth (Year 15-teen). Logistic regressions were estimated to evaluate how teen attributes and social contexts were associated with the odds that a specific romantic relationship was initiated online. Separate models were estimated for male and female respondents to test for gender differences in online partner search. Because covariates were measured for respondents, standard errors were adjusted for clustering at the individual level. Each observation was weighted using 1/n, where n is the number of relationships for each teen because teens contributed different numbers of observations to the relationship sample. All models controlled for socioeconomic background and demographic characteristics associated with adolescent dating (King and Harris, 2007). Finally, several relationship attributes, including type, duration, quality, and partner characteristics, were compared to evaluate claims that romantic relationships initiated online are less salutary than those formed in person.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Descriptive statistics reported in Table 1 reveal that roughly two-thirds of mDiary respondents (359/531) reported one or more romantic partners during the study. There are several noteworthy differences between the sample of teens who reported one or more romantic partners over the observation period (analysis sample) and those who did not. These differences, which portray selection into the analysis sample, could potentially influence teens’ propensity to search for romantic partners online. The gender composition of the analysis sample is skewed toward females, but the ethno-racial composition of teens who did and did not report partners did not differ significantly. That Blacks and Hispanics comprised nearly 60% of mDiary respondents reflects the sampling frame of the FFCWS parent study, which oversampled births to low-income and unmarried mothers. As indicated in the bottom panel, only one-third of mothers were married when the target child was born, roughly one-in four lacked high school diplomas, and less than 20% were foreign born. Differences in the nativity composition of teens who reported one or more partners and those who reported none (p< 0.05) potentially signals cultural differences in support of dating (King and Harris, 2007).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics of mDiary Respondents by Partner Mentions (means or percentages; unit of analysis = teen)

| Full Sample (N=531) | One or More Partner Mentions (N = 359) | No Partner Mentions (N = 172) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| TEEN ATTRIBUTES | ||||

| Female | 55.2 | * | 58.5 | 48.3 |

| Race | ||||

| nonHispanic White | 27.7 | 28.1 | 26.7 | |

| nonHispanic Black | 32.0 | 33.4 | 29.1 | |

| Hispanic | 26.7 | 26.7 | 26.7 | |

| Other | 13.6 | 11.7 | 17.4 | |

| Socio-emotional adjustment | ||||

| Closeness to mother at age 9 | ||||

| Extremely close | 73.3 | 73.5 | 72.7 | |

| Quite close | 18.8 | 19.2 | 18.0 | |

| Fairly or not very close/no contact past year | 7.9 | 7.3 | 9.3 | |

| Closeness to father at age 9 | ||||

| Extremely close | 49.3 | 50.4 | 47.1 | |

| Quite close | 19.8 | 19.2 | 20.9 | |

| Fairly close or not close | 13.9 | 14.8 | 12.2 | |

| No contact past year | 17.0 | 15.6 | 19.8 | |

| Closeness to parents at mDiary baseline | ||||

| Extremely close | 39.7 | 39.0 | 41.3 | |

| Quite close | 37.7 | 38.2 | 36.6 | |

| Fairly or not very close | 22.6 | 22.8 | 22.1 | |

| Disobedient at school (1=often/sometimes) | 19.0 | 19.5 | 18.0 | |

| Fits in well at school | ||||

| Strongly agree | 38.4 | 36.5 | 42.4 | |

| Somewhat agree | 48.6 | 51.3 | 43.0 | |

| Disagree or home schooled | 13.0 | 12.3 | 14.5 | |

| Makes friends easily (1 = often true) | 60.6 | *** | 65.5 | 50.6 |

| Prior Dating Experience/Attraction | ||||

| Ever dated by mDiary baseline | 73.3 | *** | 83.8 | 51.2 |

| Ever same-sex crush | 18.5 | * | 21.2 | 12.8 |

| PROXIMATE CONTEXT | ||||

| Peers | ||||

| All/most friends dating | 41.4 | *** | 47.4 | 29.1 |

| Daily weekday hrs. online with friends | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.4 | |

| (s.d.) | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 | |

| Family | ||||

| Live with both bio parents @ age15 | 39.0 | 37.1 | 43.0 | |

| # Mom’s partner transitions (youth ages 9–15) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | |

| (s.d) | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | |

| Parents approve dating | 61.0 | *** | 66.0 | 50.6 |

| Parents often monitor youth free time | 51.0 | 50.7 | 51.7 | |

| Digital Access/Exposure | ||||

| Mobile web access | 84.9 | 86.4 | 82.0 | |

| Daily weekday hrs. surfing web/shopping online | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | |

| (s.d.) | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.4 | |

| SOCIAL BACKGROUND | ||||

| Mother’s Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 23.5 | 23.4 | 23.8 | |

| HS or equivalent | 27.9 | 29.3 | 25.0 | |

| Some college | 31.5 | 32.0 | 30.2 | |

| College graduate | 17.1 | 15.3 | 20.9 | |

| Parents married at teens’ birth | 34.1 | 32.3 | 37.8 | |

| Mother foreign born | 18.1 | * | 15.6 | 23.3 |

Source: FFCWS Baseline survey; Year-9 Child survey; Year-15 Parent and Teen Surveys; mDiary surveys

Teens with and without partner mentions:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<.001.

The parental closeness measures reveal greater attachment to mothers than to fathers at age 9. During the Year-9 interview, 73% of youth reported feeling extremely close to their mothers, but only half reported similar attachment to their fathers. To some extent the differences in closeness to mothers and fathers at age 9 reflect parent absence—about 17% of teens had no contact with their father and 8% had no contact with their mother in the prior year. The mDiary measure of closeness, which referred to both parents and did not separately record parent absence, revealed that only 40% of teens felt extremely close to their parents at age 16 and nearly one-in-four felt fairly close or not close at all to their parents.

Respondents in the analysis sample differed from teens who did not mention a romantic partner during the study in several ways, including sociability, prior dating experience, embeddedness in dating networks, and same-sex attraction. Nearly two thirds of the analysis sample reported that they made friends easily compared with only half of their peers who did not mention any partners (p <0.001). Furthermore, compared with teens who did not report a partner during the study, higher shares of the analysis sample reported prior dating experience (84% vs. 51%, respectively; p<0.001) and embeddedness in peer networks where all or most friends were dating (47% vs. 29%, respectively, p<0.001). One-in-five teens in the analysis sample reported a same-sex attraction compared with 13% of their peers who did not mention a partner (p<0.05). Parental support for dating also was slightly higher among the teens who reported one or more romantic partners during the study versus their peers who reported none (66% vs. 51%, respectively; p<0.05). Whether these attributes predispose teens to search for romantic partners online is an empirical question addressed below.

Partner Meeting Venues

The distribution of the meeting venues for the 706 relationships reported during the mDiary study is shown in Table 2. Respondents in the analysis sample averaged two romantic relationships during the study (mean = 1.97; SD = 1.33), with no significant differences between males and females (male mean = 1.91; SD = 1.22; female mean = 2.00; SD = 1.41). About half (52%) of teens reported only one romantic relationship, but one-quarter reported three or more romantic relationships during the observation period.

Table 2.

Distribution of Partner Meeting Venues by Gender (means or percentages; unit of analysis = relationship)

| Meeting venues | All Respondents (N=706) | Male Respondents (N=284) | Female Respondents (N=422) |

|---|---|---|---|

| School % | 58.1 | 63.0 | 54.7 |

| Internet % | 15.2 | 12.7 | 16.8 |

| Friends/party/neighborhood % | 14.0 | 12.3 | 15.2 |

| Church/work % | 5.1 | 3.9 | 5.9 |

| Extracurricular/camp % | 5.7 | 6.7 | 5.0 |

| Other % | 2.0 | 1.4 | 2.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Mean # relationships | 1.97 | 1.91 | 2.0 |

| SD | 1.33 | 1.22 | 1.41 |

| Number of teens | 359 | 149 | 210 |

Source: mDiary Surveys 2–26

Considering that virtually all respondents were enrolled in school when the study began, it is unsurprising that school was the modal venue where adolescents initiated romantic relationships: over half (58%) of romantic partnerships reported during the observation period were initiated at school. For the mDiary sample, the Internet rivaled friends, parties, and neighborhoods as the second most common venue to initiate a romantic relationship; moreover, the mDiary share of relationships initiated online—15%--is virtually identical to the estimate reported in a national study (Lenhart et al., 2015).

There are noteworthy gender differences in venues where teens initiate romantic relationships. The index of dissimilarity (ID), a commonly used measure to summarize the evenness of two distributions, indicates that 10 percent of the respondents would have to change meeting venue for the gender distributions to be equal. The largest contributors to unevenness are school and the Internet. Nearly two-thirds of romantic relationships reported by males were initiated in school compared with only 55% of those reported by females. Roughly 17% of romantic relationships reported by females were initiated online compared with 13% of those reported by males. Multivariate analyses are needed to evaluate how teen attributes and their proximate social contexts are associated with the odds of initiating a romantic relationship online, and whether the factors linked to adolescents’ propensity to initiate a romantic relationship online are uniform for males and females.

Multivariate Analyses

Odds ratios based on three logistic regressions predicting whether a romantic relationship was initiated online are reported in Table 3. For the pooled model, only three covariates were significantly associated with the odds that a relationship was initiated virtually. Hispanic youth were about half as likely as their non-Hispanic white peers to initiate a romantic relationship online, but no racial differences emerged.

Table 3.

Odds that Partners First Met Online (Odds ratios; all relationship types; unit of analysis = relationship)

| All Respondents (N=706) | Male Respondents (N=284) | Female Respondents (N=422) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| TEEN ATTRIBUTES | ||||||

| Female | 0.889 | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| nonHispanic White | ref | ref | ref | |||

| nonHispanic Black | 0.631 | 0.778 | 0.536 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.416 | * | 0.093 | * | 0.500 | |

| Other | 0.688 | 0.115 | ** | 1.048 | ||

| Socio-emotional adjustment | ||||||

| Closeness to mother at age 9 | ||||||

| Extremely close | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Quite close | 0.981 | 0.163 | 1.638 | |||

| Fairly or not very close/no contact past year | 1.352 | 5.304 | 0.565 | |||

| Closeness to father at age 9 | ||||||

| Extremely close | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Quite close | 1.181 | 6.757 | 0.515 | |||

| Fairly or not very close | 1.596 | 2.488 | 2.021 | |||

| No contact past year | 1.890 | 9.146 | 1.073 | |||

| Closeness to parents at mDiary baseline | ||||||

| Extremely close | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Quite close | 1.306 | 4.069 | 0.982 | |||

| Fairly or not very close | 1.072 | 3.616 | 0.653 | |||

| Disobedient at school (1=often/sometimes) | 0.780 | 1.856 | 0.765 | |||

| Fits in well at school | ||||||

| Strongly agree | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Somewhat agree | 2.193 | * | 0.761 | 4.981 | ** | |

| Disagree or home schooled | 1.100 | 0.040 | * | 2.767 | ||

| Makes friends easily (1 = often true) | 0.650 | 0.910 | 0.455 | * | ||

| Prior Dating Experience/Attraction | ||||||

| Ever dated by mDiary baseline | 0.746 | 0.339 | 0.962 | |||

| Ever same-sex crush | 1.764 | 2.116 | 1.671 | |||

| PROXIMATE CONTEXT | ||||||

| Peers | ||||||

| All/most friends dating | 0.929 | 0.774 | 0.843 | |||

| Daily weekday hrs. online with friends | 1.011 | 1.016 | 1.025 | |||

| Family | ||||||

| Live with both bio parents @ age15 | 0.746 | 1.483 | 0.521 | |||

| # Mom’s partner transitions (youth ages 9–15) | 0.771 | 0.787 | 0.698 | |||

| Parents approve dating | 0.816 | 0.710 | 0.626 | |||

| Parents often monitor youth free time | 0.855 | 2.388 | 0.803 | |||

| Digital Access/Exposure | ||||||

| Mobile web access | 1.615 | 3.395 | * | 2.133 | ||

| Daily weekday hrs. surfing web/shopping online | 1.196 | * | 1.036 | 1.151 | ||

| SOCIAL BACKGROUND | ||||||

| Mother’s Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 1.779 | 2.530 | 1.386 | |||

| High school or equivalent | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Some college | 0.666 | 0.048 | * | 1.006 | ||

| College graduate | 0.467 | 0.163 | * | 0.731 | ||

| Parents married at teens’ birth | 1.500 | 5.572 | ** | 1.045 | ||

| Mother foreign born | 0.871 | 3.893 | 0.487 | |||

| Constant | 0.135 | * | 0.036 | 0.110 | * | |

| Pseudo R-Square | 0.100 | 0.327 | 0.154 | |||

Source: FFCWS Baseline survey; Year-9 Child survey; Year-15 Parent and Teen Surveys; mDiary surveys

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<.001.

Estimates weighted and robust standard errors

Fitting in well at school facilitates the development of romantic relationships because schools are primary social spheres for adolescents’ friendships and the modal venue for initiating romantic relationships. Compared with peers who strongly agree that they fit in well at school, teens who only somewhat agree that they fit in well at school well were twice as likely to initiate a romantic partnership online. None of the measures capturing peer and family influences were significantly associated with the odds that a romantic relationship was initiated online; however, the number of weekly hours teens spent surfing the web was associated with 19% higher odds that a romantic relationship was initiated online. Although 21% of respondents reported ever having been attracted to a same-sex peer, the point estimate indicating higher odds that a romantic relationship was initiated online was on the margin of statistical significance (p=0.06).

The gender-specific analyses revealed notable differences in model fit as well as correlates of male and female adolescents’ propensity to initiate romantic partnerships online. The model explained one-third of the variance in the likelihood that male relationships were initiated online compared with only 15% for female relationships. The odds that males’ romantic relationships were initiated online were associated with family socioeconomic status, including whether parents were married at birth, their access to a mobile device, ethno-racial status, and fit in school. By contrast, only two measures of socio-emotional adjustment were significantly associated with the likelihood that girls initiated a romantic online—namely sociability and school fit.

Compared with romantic relationships of nonHispanic White males, those of Hispanic and Asian or mixed-race youth were less likely to have been initiated online. No similar association obtained for girls, however. Further, relative to their male peers who strongly agreed they fit well in school, relationships of males who disagreed or were home schooled were only 4% as likely to have been initiated online; however, there were no statistical differences between males who somewhat agreed about fitting in well at school and those who strongly agreed with the statement.

School fit and ease of making friends were two aspects of girls’ socio-emotional adjustment associated with their propensity to initiate romantic relationships online. Compared with their peers who strongly agreed that they fit well in school, romantic relationships reported by girls who only somewhat agreed were almost 5 times as likely to have been initiated online. Furthermore, girls who easily make friends were only half as likely to report that a romantic relationship was initiated online compared with their peers who do not, but no comparable association obtained for boys. Taken together, these estimates lend support to claims that the Internet serves as a social intermediary for girls with weak social skills, but not for boys, for whom access to a mobile device is paramount for initiating online romantic relationships.

Neither the pooled nor gender-specific models showed associations between the odds that a romantic relationship was formed virtually and any of the parent closeness or school externalizing behavior measures. Embeddedness in networks of dating peers also did not increase the odds that adolescents initiated romantic relationships online. That the results do not support claims that parents’ monitoring behavior or approval of dating are associated with the propensity of teens to initiate romantic relationships online partly may reflect the high share of teens with dating experience (Table 1), which presumes prior experience navigating parental monitoring of dating, irrespective of meeting venue.

Relationship Attributes

There is scant information about whether adolescent partnerships formed virtually are less salutary or of lower quality compared with those formed in person (Blunt-Vinti et al., 2016). The mDiary study recorded bi-weekly changes in relationship type, duration, quality, abusive behavior, and frequency of in-person intimate and sexual contact to address this question. The top panel of Table 4 provides a distribution of relationship types and first transitions observed within the observation period according to meeting venues.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Relationships by Meeting Venue (Means or Percentages)

| All Relationships (N=706) | In Person (N=599) | Online (N=107) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Relationship Type | ||||

| % always talking/flirting | 13.0 | 12.4 | 16.8 | |

| % always dating | 12.6 | 13.5 | 7.5 | |

| % always friends with benefits | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | |

| % always othera | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| % talking/flirting to dating | 25.8 | 26.9 | 19.6 | |

| % talking/flirting to friends with benefits | 12.9 | 12.4 | 15.9 | |

| % talking/flirting to other | 8.7 | 9.0 | 7.5 | |

| % dating to talking/flirting | 15.3 | 14.5 | 19.6 | |

| % dating to friends with benefits | 2.1 | 2.3 | 0.9 | |

| % dating to other | 2.8 | 2.5 | 4.7 | |

| % friends with benefits to talking/flirting | 1.8 | 1.5 | 3.7 | |

| % friends with benefits to dating | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.9 | |

| Survey Mentions b | ||||

| Mean | 6.0 | 6.2 | 5.1 | |

| (s.d.) | 6.9 | 7.0 | 6.1 | |

| % less than 2 survey mentions | 43.9 | 43.4 | 46.7 | |

| % more than 20 survey mentions | 9.5 | 9.9 | 7.5 | |

| Relationship Quality & In-person Contact | ||||

| Average quality very good or excellent | 50.5 | 51.1 | 47.4 | |

| Weekly in-person contact frequency (days)c | 2.2 | *** | 2.4 | 1.1 |

| (s.d.) | (0.07) | (0.08) | (0.15) | |

| Non-intercourse sexual activity in any diary | 33.0 | * | 34.6 | 24.3 |

| Sexual intercourse in any diary | 23.1 | 24.0 | 17.8 | |

| Abusive or controlling behavior in any diaryd | 13.3 | 13.9 | 10.8 | |

| Partner Characteristics | ||||

| Age congruence | ||||

| Age 2+ years different | 17.3 | ** | 15.2 | 29.0 |

| Age 3+ years different | 4.8 | ** | 3.7 | 11.2 |

| Same sex | 5.7 | 5.3 | 7.5 | |

Source: mDiary Study Surveys 2–26

Notes: t-test or Chi-sq between online and in person

P<.0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001

Teen write-in responses: complicated, unsure or friends

Number of surveys partnership reported

5 missing values assigned to modal category of zero

Respondent reported controlling and/or emotionally or physically abusive behavior by self or partner in any diary

One striking feature is the amount of temporal variation in the way adolescents characterized their romantic relationships. Irrespective of meeting venue, most romantic relationships began with flirting/talking (Baker and Carreño, 2016). Nearly 40% of relationships initially reported as talking/flirting transitioned to dating or friends with benefits, and an additional 9% morphed into a more ambiguous status signaled by teen write-in responses such as “it’s complicated” or “unsure”. Possibly signaling pending dissolution, 15% of dating relationships transitioned to talking/flirting. Just over one-in-four relationships did not involve a change in type during the mDiary study window (talking/flirting; dating, friends with benefits and “other,” which capture write-in statuses); due to left censoring, it is not possible to ascertain which of these partnerships had a different status prior to their first report in mDiary (one-third were in progress before first report). Chi-square tests revealed no significant differences between any of the relationship trajectory contrasts according to meeting venue.

Volatility of adolescent partnerships is further illustrated by their short duration: average duration of reported romantic relationships was 12 weeks (6 survey mentions) and 44% lasted one month or less, but the large standard deviation for mean duration indicates considerable heterogeneity in relationship longevity. Roughly 10% of relationships were reported in more than 20 diaries, but no differences in duration according to meeting venue were statistically significant. Only 6% of all partnerships captured during the observation window involved same-sex partners, but the differences by meeting venue were not statistically significant (5.3% vs. 7.5% of relationships initiated in-person and online, respectively).

Claims that partnerships formed online are riskier than those formed offline find mixed support in Table 4. On the one hand, neither average relationship quality nor the incidence of partner abuse or sexual intercourse differ statistically according to relationship initiation venue. Rather, over one-third of partnerships formed in person involved non-intercourse sexual activity, compared with about one-quarter of those formed virtually (34.6% vs. 24.3%; p<0.05). Partly this is because partnerships formed online involved fewer in-person weekly contacts than those formed offline (1.1 vs. 2.4, respectively; p<0.001), hence lower exposures to physical intimacy. On the other hand, romantic relationships formed virtually involved a higher degree of partner age incongruence compared with those formed in person. Almost twice as many romantic relationships formed online involved age disparities of two or more years (p<0.01) and three times as many involved age gaps of three or more years (p<0.01). Prior research has found that age asymmetrical adolescent relationships are associated with various risks, including early sexual debut (Kaestle et al., 2002), reduced use of contraception (Kusunoki and Upchurch, 2011), pregnancy (Ryan et al., 2008), and intimate partner violence (Cooper et al., 2021).

Discussion

Despite extensive evidence that digital technology has transformed how youth communicate with peers, there is limited evidence about the extent to which the Internet has become a social intermediary enabling adolescents to search for romantic partners. Much more is known about adolescents’ use of digital technology to maintain and dissolve than to initiate romantic relationships, partly because of a pervasive reliance on cross-sectional designs that lack measurement precision needed to capture their emergence and partly due to inconsistent terminology and definitions. Whether adolescent romantic relationships initiated online are less salutary than those formed in-person remains an open question because most scholarship takes a problem-centered approach that skews to identifying risks and largely eschews consideration of how and where relationships emerged. The current study addressed both gaps by using diary methods to track the emergence and evolution of romantic relationships, and to evaluate whether and in what ways relationships initiated online differed from those formed in-person.

The ambiguous beginnings of adolescent romantic relationships and the inconsistent terminology used to characterize them is widely acknowledged, but whether these differences are more salient for relationships initiated digitally versus in-person is unclear. That the current study considered “talking and flirting” as a romantic relationship explicitly recognizes both how teens use digital technology to cultivate romantic relationships and also that relationships initiated online can only begin as talking and flirting. Over 40% of relationships initially reported as talking/flirting transitioned to dating or sexual relationships, but there were no differences in transition rates according to meeting venues.

School was the modal venue where mDiary teens initiated their romantic relationships, but apparently males and females navigate complex high school cultures differently. Teens who strongly agreed that they fit in well at school were more likely to form romantic relationships in person compared with their less sociable peers. Gender moderated this association, revealing that only girls who did not fit in well at school and those who did not easily make friends were more likely to search for romantic partners online than their peers who fit well in school and made friends easily. Although it was expected that youth who ever reported a same sex attraction would be more likely to form romantic relationships virtually than their peers who did not (Korchmaros et al., 2015), the point estimate was not statistically significant. In part this is because of the small sample size and the low incidence of same-sex relationships among adolescents in the sample.

Attachment and developmental psychopathology perspectives of adolescent romance suggest that stable family environments are conducive to healthy adolescent romantic relationships (Goldberg et al., 2019b); however, results showed no statistical associations between partnering venues and any of the parent closeness or family instability measures. It is conceivable that family structure and stability are associated with whether relationships are initiated in the first place, but not where or how they are formed. Prior research with less granular temporal measurement found inconsistent associations between parent monitoring and adolescents’ romantic relationships (Longmore et al., 2009). In fact, existing studies not only disagree about the most effective strategies for monitoring teens’ digital behavior, but also acknowledge that teens’ online behavior can both improve or worsen socio-emotional states, depending on offline vulnerabilities (Coyne et al., 2017).

Rather than show that romantic relationships initiated online pose greater risks than those formed in-person, the current study indicates that the nature of risks differ. Partly because they have more frequent in-person contact, teens involved in romantic relationships initiated in person may be more likely to become sexually active, as evidenced by higher rates of non-intercourse sexual activity compared with teens who initiated a romantic relationship online. Nevertheless, romantic relationships initiated virtually may face different risks, indicated by larger age disparities, which often involve partner power asymmetry (Catallozzi et al., 2011) and potential for abusive and controlling behavior (Cooper et al., 2021). Significant differences by meeting venue were not apparent for the other dimensions of relationship quality considered.

Limitations

Despite the novelty of the mDiary design, the current study has several limitations that warrant mention. First, to track partnerships over time, respondents were asked to provide either initials, first names or nicknames for each new relationship. Analyses were based on named relationships, which underestimated all relationships reported during the observation period. Although this limitation implies that reported associations are conservative, it is not possible to know with certainty whether partners met online were more likely to go unnamed compared with those formed in-person, or whether gender differences in naming partners biased findings. Hence, the direction of possible biases is unknown. Estimates of relationship duration are likely understated owing to both left and right censoring. Also, as in most studies about adolescent dating, relationships are based on reports from individual teens rather than couples (River et al., 2021). And, despite granular temporal measurements, it is not possible to infer that the reported associations are causal.

External validity of the findings is limited owing to multiple sources of sample selection biases. First, although mDiary respondents were recruited from a study with a known sampling frame, the parent study sampled only births occurring in metropolitan areas and disproportionately sampled mothers who were unmarried at the time of the target child’s birth. Controls for mothers’ educational attainment and marital status at the birth of the target youth can only partly mitigate these limitations. Second, not all respondents reported an active romantic relationship during the observation period; although three-quarters of respondents reported having ever dated prior to enrolling in the mDiary study, only two-thirds reported one or more active romantic relationships during the observation period. Results are conditioned on reporting an active relationship during the observation period. Although half of teens who did not report a partner had dated in the past, they differed from the analysis sample in their sociability, prior dating experience, embeddedness in peer dating networks, and parental support for dating. Half of teens who did not mention a romantic partner during the study had no prior dating experience; therefore, it is unclear whether their inclination to search for partners online would match that of their peers who reported active relationships during the observation period. A final limitation concerns the relatively small sample size, which inevitably resulted in underpowered estimates.

Conclusion

Digital technology has broadened romantic partner search beyond peer networks formed in school, places of worship, and during extracurricular social activities, but whether relationships initiated online are more risky than those formed in-person has been unclear. The current study used diary methods to evaluate the circumstances associated with initiation of adolescent romantic relationships and to evaluate their quality. School remains the modal venue where adolescents initiate romantic relationships; however, the Internet and social media rivaled “friends, parties and neighborhoods” as the second most common venue where adolescents initiate romantic relationships. Digital technology allows adolescents, particularly girls who are less sociable and who do not fit in well at school, to broaden dating pools. For teens who are less well-adjusted offline, the Internet has become a social intermediary to find romantic partners. Claims that adolescent romantic relationships formed online pose higher risks than those formed offline were largely unsupported, with the notable exception of greater age asymmetry. Rather than presume that online partnering is inherently risky for teens, future research should consider how the Internet and social media both facilitate and undermine the development of salutary romantic relationships.

Contributor Information

Marta Tienda, Princeton University.

Rachel E. Goldberg, University of California, Irvine

Jay R. Westreich, Fannie Mae

References

- Ahern NR, & Mechling B (2013). Sexting: Serious problems for youth. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 51(7), 22–30. 10.3928/02793695-20130503-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP (2008). The attachment system in adolescence. In Cassidy J & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications, 2nd ed (pp. 419–435). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M (2015, August 20). How having smartphones (or not) shapes the way teens communicate. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 23, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/08/20/how-having-smartphones-or-not-shapes-the-way-teens-communicate/ [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M (2016, January 7). How parents monitor their teen’s digital activities. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 23, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/07/parents-teens-digital-monitoring/ [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, & Jiang J (2018, May 31). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 31, 2019, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MVLB, Goldberg N, Conron KJ, & Gates GJ (2009). Best practices for asking questions about sexual orientation on surveys (SMART). The Williams Institute. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/smart-so-survey/ [Google Scholar]

- Baker CK, & Carreño PK (2016). Understanding the role of technology in adolescent dating and dating violence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(1), 308–320. 10.1007/s10826-015-0196-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blunt-Vinti HD, Wheldon C, McFarlane M, Brogan N, & Walsh-Buhi ER (2016). Assessing relationship and sexual satisfaction in adolescent relationships formed online and offline. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(1), 11–16. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhi ER, Cook RL, Marhefka SL, Blunt HD, Wheldon C, Oberne AB, Mullins JC, & Dagne GA (2012). Does the Internet represent a sexual health risk environment for young people? Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 39(1), 55–58. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318235b3c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, & Udry JR (2003). National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In Florsheim P (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 23–56). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Catallozzi M, Simon PJ, Davidson LL, Breitbart V, & Rickert VI (2011). Understanding control in adolescent and young adult relationships. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(4), 313–319. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, & Furman W (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 631–652. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LM, Longmore MA, Manning WD, & Giordano PC (2021). The influence of demographic, relational, and risk asymmetries on the frequency of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Journal of Family Issues, 42(1), 136–155. 10.1177/0192513X20916205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne SM, Padilla-Walker LM, & Holmgren HG (2017). A six-year longitudinal study of texting trajectories during adolescence. Child Development, 89(1), 58–65. 10.1111/cdev.12823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn HK, Felmlee DH, & Conger RD (2017). The social context of adolescent friendships: Parents, peers, and romantic partners. Youth & Society, 49(5), 679–705. 10.1177/0044118X14559900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H, & Brown BB (2001). Primary attachment to parents and peers during adolescence: Differences by attachment style. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(6), 653–674. 10.1023/A:1012200511045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George MJ, Russell MA, Piontak JR, & Odgers CL (2018). Concurrent and subsequent associations between daily digital technology use and high-risk adolescents’ mental health symptoms. Child Development, 89(1), 78–88. 10.1111/cdev.12819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC (2003). Relationships in adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 257–281. 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Longmore MA, & Manning WD (2006). Gender and the meanings of adolescent romantic relationships: A focus on boys. American Sociological Review, 71(2), 260–287. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg RE, Koffman D, & Tienda M (2019a). Using bi-weekly surveys to portray adolescent partnership dynamics: Lessons from a mobile diary study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(3), 646–661. 10.1111/jora.12472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg RE, & Tienda M (2017). Adolescent romantic relationships in the digital age. In Scott RA & Kosslyn S (Eds.), Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences. 10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0426 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg RE, Tienda M, & Adserà A (2017). Age at migration, family instability, and timing of sexual onset. Social Science Research, 63(Supplement C), 292–307. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg RE, Tienda M, Eilers M, & McLanahan SS (2019b). Adolescent relationship quality: Is there an intergenerational link? Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(4), 812–829. 10.1111/jomf.12578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen-Wells MA, James SL, & Holmes EK (2021). Attachment development in adolescent romantic relationships: A conceptual model. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(1), 128–142. 10.1111/jftr.12409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, & Udry JR (2000). You don’t bring me anything but down: Adolescent romance and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(4), 369–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Morisky DE, & Wiley DJ (2002). Sexual intercourse and the age difference between adolescent females and their romantic partners. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34(6), 304–309. JSTOR. 10.2307/3097749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney B, Beckett MK, Collins RL, & Shaw R (2007). Adolescent romantic relationships as precursors of healthy adult marriages: A review of theory, research, and programs. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR488.html [Google Scholar]

- King RB, & Harris KM (2007). Romantic relationships among immigrant adolescents. International Migration Review, 41(2), 344–370. 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00071.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korchmaros JD, Ybarra ML, & Mitchell KJ (2015). Adolescent online romantic relationship initiation: Differences by sexual and gender identification. Journal of Adolescence, 40, 54–64. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki Y, & Upchurch DM (2011). Contraceptive method choice among youth in the United States: The importance of relationship context. Demography, 48(4), 1451–1472. 10.1007/s13524-011-0061-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Anderson M, & Smith A (2015, October 1). Teens, technology and romantic relationships. Pew Research Center & Technology. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/01/teens-technology-and-romantic-relationships/ [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA, Eng AL, Giordano PC, & Manning WD (2009). Parenting and adolescents’ sexual initiation. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71(4), 969–982. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00647.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A, & Allen G (2009). Romantic relationships from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Sociological Quarterly, 50(2), 308–335. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01142.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittleman J (2019). Sexual minority bullying and mental health from early childhood through adolescence. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers C (2018). Smartphones are bad for some teens, not all. Nature, 554(7693), 432. 10.1038/d41586-018-02109-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özgür H (2016). The relationship between internet parenting styles and internet usage of children and adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 411–424. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman M, & Reich B (2016). Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 155–167. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pujazon-Zazik MA, Manasse SM, & Orrell-Valente JK (2012). Adolescents’ self-presentation on a teen dating web site: A risk-content analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(5), 517–520. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LA, Conn K, & Wachter K (2020). Name-calling, jealousy, and break-ups: Teen girls’ and boys’ worst experiences of digital dating. Children and Youth Services Review, 108. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LA, Tolman RM, & Ward LM (2017). Gender matters: Experiences and consequences of digital dating abuse victimization in adolescent dating relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 59, 79–89. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LA, Tolman RM, Ward LM, & Safyer P (2016). Keeping tabs: Attachment anxiety and electronic intrusion in high school dating relationships. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 259–268. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2001). Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23(4), 303–326. 10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00141-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V, & Robb MB (2019). The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens, 2019. Common Sense Media. Retrieved August 15, 2020, from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-2019 [Google Scholar]

- River LM, O’Reilly Treter M, Rhoades GK, & Narayan AJ (2021). Parent-child relationship quality in the family of origin and later romantic relationship functioning: A systematic review. Family Process. 10.1111/famp.12650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo CJ, Collibee C, Nugent NR, & Armey MF (2019). Let’s get digital: Understanding adolescent romantic relationships using naturalistic assessments of digital communication. Child Development Perspectives, 13(2), 104–109. 10.1111/cdep.12320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AA, Ha T, Updegraff KA, & Iida M (2018). Adolescents’ daily romantic experiences and negative mood: A dyadic, intensive longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(7), 1517–1530. 10.1007/s10964-017-0797-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Cauffman E, & Spieker S (2008). The developmental significance of adolescent romantic relationships: Parent and peer predictors of engagement and quality at age 15. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(10), 1294. 10.1007/s10964-008-9378-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MJ, & Thomas RJ (2012). Searching for a mate: The rise of the internet as a social intermediary. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 523–547. 10.1177/0003122412448050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S, Franzetta K, Manlove JS, & Schelar E (2008). Older sexual partners during adolescence: Links to reproductive health outcomes in young adulthood. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 40(1), 17–26. 10.1363/4001708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soller B (2014). Caught in a bad romance: Adolescent romantic relationships and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 56–72. 10.1177/0022146513520432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov E-H, Paradis A, & Godbout N (2021). Teen dating relationships: How daily disagreements are associated with relationship satisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(8), 1510–1520. 10.1007/s10964-020-01371-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Pasch LA, Flores E, VanOss Marin B, Marco Baisch E, & Wibbelsman CJ (2008). Nonviolent aspects of interparental conflict and dating violence among adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 30(3), 295–319. 10.1177/0192513X08325010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turney K, & Goldberg RE (2019). Paternal incarceration and early sexual onset among adolescents. Population Research and Policy Review, 38(1), 95–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venta A, Shmueli-Goetz Y, & Sharp C (2014). Assessing attachment in adolescence: A psychometric study of the child attachment interview. Psychological Assessment. 10.1037/a0034712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Bianchi SM, & Raley SB (2005). Teenagers’ internet use and family rules: A research note. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(5), 1249–1258. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00214.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen CKF, Schneider S, Stone AA, & Spruijt-Metz D (2017). Compliance with mobile ecological momentary assessment protocols in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(4), e132. 10.2196/jmir.6641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2002). The development of romantic relationships and adaptations in the system of peer relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(6), 216–225. 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00504-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]