Abstract

Background:

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected health care institutions, introducing new challenges for nurse leaders and their colleagues. However, little is known about how the pandemic has specifically affected the lives of these leaders and what methods and strategies they are using to overcome pandemic-related challenges.

Objectives:

Examine the effect of the 2019 pandemic on emerging health care leaders and highlight methods and strategies they used to overcome pandemic-related challenges.

Methods:

The participants in this study represent a diverse group of interprofessional health care faculty enrolled in a transformational leadership course (Paths to Leadership [PTL]) when the pandemic first appeared. Three months into the pandemic, the leadership cohort was invited to participate in this qualitative study, exploring four questions: Q1: How have you transformed your working styles in response to the pandemic? Q2: How have you adjusted your personal life in response to the pandemic? Q3: How have you used leadership skills learned from PTL during the pandemic? and Q4: What lessons have you learned from the pandemic? Participant narratives were analyzed by a team of nurse researchers using conventional qualitative content analysis.

Results:

Themes for Q1 (Working Styles) included: shifted from face-to-face to telework, faced novel disease and decisions, worked more from home, and challenged to maintain contact with professional peers and team. Themes for Q2 (Personal Life) included: accommodate adults working and children learning from home, looked for and found the positive, and continue to struggle. Themes for Q3 (Leadership Skills) included: reflective practice, listening, holding, and reframing. Finally, themes for Q4 (Pandemic Lessons) included: leadership, human connection, be prepared, taking care of ourselves, and connecting with nature.

Discussion:

The 2019 pandemic brought hardships and opportunities to faculty members enrolled in an interprofessional transformational leadership course. In conjunction with this course, the pandemic provided a unique opportunity for participants to apply newly acquired relationship building, positive organizational psychology, and reframing skills during a time of crisis. Nursing leaders, whose educational offerings may be immediately “put to the test,” may find our lessons learned are helpful as they develop strategies to cope with unanticipated future challenges.

Keywords: COVID-19, health care leaders, leadership

The 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) led to immediate and dramatic changes in academic health care system’s clinical, research, educational, and administrative practices in the United States. Clinical duties were significantly reduced due to local government orders to delay nonurgent and elective procedures. Non-COVID-19 research was temporarily ceased, leading to detrimental consequences for nonmodifiable studies. University courses and continuing professional development events in the Schools of Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, and Public Health were transitioned to online-only or postponed, with professional travel prohibited. Trainees at all levels were abruptly transitioned to virtual learning in place of in-person, hands-on experiences.

When modified clinical operations resumed, health care professionals, researchers, faculty, and students faced new challenges; clinicians also needed to manage the clinical support staff, who were anxious as new infection control processes were enacted and transmission risk remained uncertain. In short, the COVID-19 pandemic posed one of the toughest current leadership tests to date (Hatami et al., 2020). Everyone can learn from others, especially when sharing leadership experiences amid a crisis (Forster et al., 2020; Shingler-Nace, 2020). In this paper, we explore the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on leadership trainees who were in the midst of a transformational leadership course—Paths to Leadership (PTL) —at the onset of the pandemic.

PTL is a 23-week interprofessional faculty development program that encourages learners to identify and facilitate desired changes in clinical practice, education, and research by building relationships (Steckler & Huntzicker, 2015). In PTL, leadership is defined as working collaboratively to accomplish goals in an interprofessional environment, recognizing that leadership can happen at all levels of an organization (Steckler, 2019). Both the formal PTL curriculum and the practical role modeling from institutional leaders and course directors emphasize learning by doing, providing ongoing opportunities to practice leadership skills in meaningful contexts.

In addition to these active participatory experiences, the program is organized around three themes. The first theme focuses on the power of identifying the “meaningful difference” each participant aims to make as a leader (Steckler, 2019) through practices including (a) creating an inspiring picture of a desired future, (b) using inquiry and listening to connect with others, (c) influencing colleagues up, down, and across their organization, and (d) prototyping and designing experiments. These practices have been reported as fundamental aspects of effective interprofessional leadership and innovation (Edmondson, 2013; Gino, 2019; Heath & Heath, 2010; Ibarra, 2015; Tan, 2012). The second theme emphasizes alignment across multiple work–life domains, including professional, home, community, and self, combining reflective practice with specific exercises for aligning values and priorities (Friedman, 2008). The third theme illuminates four frames (structural, human, political, and symbolic) for analyzing and influencing complex organizational challenges (Bolman & Deal, 2021).

Throughout the program, evidence-based practices for increasing mindfulness, emotional resilience, and a positive versus cynical mindset. Building in part on the work of Boyatzis et al. (2015), which focuses on the power of “positive emotional attractors” as part of emotionally “resonant” leadership, the PTL curriculum asks participants repeatedly to articulate and enroll others in their aspirational vision, while increasing their capacity for solid yet reflective leadership in complex environments. Positive psychology principles, including building on strengths, cultivating self-compassion, and mindful awareness of one’s framing and narratives about what is happening, are also practiced in the course. These relational and/or collaborative leadership skills are acquired by engaging in dynamic, facilitated exercises in a trusted community of peers (Steckler & Huntzicker, 2015). Serendipitously, when the pandemic arrived, the PTL cohort was in the midst of learning how to build relationships to influence institutional change.

The COVID-19 pandemic gave participants in the 2020 PTL course unique opportunities to develop and apply newly learned leadership skills amid a public health crisis with far-reaching implications for health-professions-related teaching, clinical practice, and research. During the first weeks of the pandemic, the cohort quickly learned and adapted to the pandemic’s changes forced upon us. Beyond existing models of crisis leadership, we delved into our “new normal” and looked to each other for support and to learn (Forster et al., 2020; Oroszi, 2018). For example, we practiced reframing, considering situations from perspectives other than one’s own, and the leadership skills of acknowledging the experiences of interprofessional team members during a crisis (Petriglieri, 2020).

We noted the far-reaching effect of COVID-19 beyond our work, career, and school obligations (Dubey et al., 2020), as our home environments, community, and individual biopsychosocial-spiritual experiences also demanded our attention. These experiences highlighted the importance of leadership skills for assessing and shifting alignment within and across life domains (Friedman, 2008). The closure of K–12 schools and university campuses, dramatic increases in unemployment, and changed requirements for meeting the basic needs of households each demanded the attention of leaders and dramatically altered the landscape of our lives, both personally and professionally. Such crises can reduce psychological safety, which is a fundamental component in mutual trust and respect, cooperative behavior, and collaboration for innovation and desired change (Dubey et al., 2020; Edmondson et al., 2020). Towards the end of the PTL course, all learners were invited to participate in a study exploring the effect of COVID-19 within and across the various domains of the lives of emerging leaders.

Methods

Participants & Setting

Thirteen members (38%) of the PTL cohort were recruited via convenience sampling. Email invitations were sent out to the entire cohort by one of the authors (ZZ). The sample included faculty, researchers, and clinicians from the Schools of Medicine and Nursing.

Procedures

This study was reviewed by the university’s institutional review board (IRB) and determined to be exempt (IRB #00020001); participants were not compensated for their participation.

Measures

Each participant provided basic demographic information about their faculty role, family characteristics, and age, as well as responses to four questions: “How have you transformed your working styles in response to the pandemic?”, “How have you adjusted your personal life in response to the pandemic?”, “How have you used leadership skills learned from PTL during the pandemic?”, and “What lessons have you learned from the pandemic?”

Analysis Plan

All responses were collected through Qualtrics survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT; http://www.qualtrics.com), de-identified, and stored in an encrypted password-protected electronic file before analysis. Using conventional qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), codes were derived directly from the participants’ responses and sorted into themes. Each transcript was independently coded and analyzed by three research team members from the School of Nursing (AT, MD, and AE). These three team members addressed any discrepancies through discussions until a 100% agreement was reached. Once the analysis was complete, findings were returned to participants for member checking to review the themes for accuracy and face validity.

Rigor & Validity

Creswell (2013) proposed that all qualitative research must embed a minimum of two verification strategies to confirm the rigor and validity of the data and analysis; this was done using five strategies in the current study. First, an investigator triangulation strategy was utilized, with data being independently coded and analyzed by three research team members (AT, MD, and AE). In addition, these three team members also addressed any discrepancies between the codes and themes present in the analysis through discussions until an agreement was reached. Second, data triangulation was embedded in the study recruitment strategy given the interprofessional nature of the PTL cohort, with data sources coming from various leaders in the Schools of Medicine and Nursing. Third, a peer debriefing strategy was conducted, with additional colleagues being invited to review the transcripts, methodology, and results. Fourth, a thick-rich description strategy was utilized via considering the context, thoughts and emotions, motivation and intentions, and meaningfulness of the participants’ responses. Finally, findings were returned to participants to review the themes for accuracy and face validity.

Results

Participant Roles

Participants had varied backgrounds, with 79% reported having a clinical role, 46% education, 25% research, and 21% administration, while the nonrespondents almost exclusively held responsibilities for clinical patient care. Respondents worked in various departments, including geriatrics, radiation medicine, otolaryngology, radiology, hospital medicine, vascular surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, neurosurgery, and general nursing. The average age was 43 years (SD = 12 years). Eighty-six percent of participants also reported being partnered, and 61% had school-aged children, with an average of two children per participant.

Conventional Qualitative Content Analysis

The results from each survey question are described in this section along with the analysis themes and supportive exemplars, which are presented in table format in the Supplemental Digital Content.

Question 1: “How Have You Transformed Your Working Styles in Response to the Pandemic Crisis?”

Four themes were identified: shifted from face to face to telework, faced novel disease and decisions, worked more from home, and challenged to maintain contact with professional peers and team.

Shifted from Face to Face to Telework.

Participants noted the various effects of moving work from in-person to distance technologies, including the closure of research laboratories, shifting teaching and precepting to video, and using telehealth to see patients and counsel those whose surgeries had to be canceled. Researcher participants reported both positive and negative effects of the required sudden changes to their work. For example, one respondent emphasized the damage that the COVID-19 pandemic inflicted on their research practice (“We had to freeze back or destroy many months’ worth of precious cell lines grown from human donor eye tissues, as well as put a stop to all ongoing research.”), while another outlined the opportunity that resulted from the pandemic (“I immediately converted my ongoing study’s recruitment part to remote mode, using work-from-home opportunities to adjust my working priorities: attending virtual meetings, online training, writing manuscripts, new grant proposals, and conducting data analyses.”). Participants’ descriptions of the effect of the pandemic-required shifts in clinical practices were overall negative (“I have adjusted to providing full-time virtual care to our patients, reassuring patients whose surgeries I had to cancel, keeping up with the barrage of new information from my two medical institutions daily.”).

Faced Novel Diseases and Decisions.

Clinicians described the steep learning curve required to respond appropriately to a novel disease, including the challenge of protecting patient safety in the face of conflicting government advice. Although participants highlighted the adverse risks for patients (“We struggled with being responsible and safe in the face of real patient needs and conflicting data.”), they also used their relationship skills to prepare to meet the challenges:

I connected with physician friends who are now practicing in other parts of the country that were faced with an earlier and larger peak of COVID-19 cases … It was important to learn from their experiences and the challenges they have faced.

Worked More from Home.

Participants noted the new experience of working from home for most or all aspects of work, including significant elements of patient care now conducted via telehealth technologies (“All of my work has been completed from home via telemedicine, emails, phone calls, and video meetings.”).

Challenged to Maintain Contact with Professional Peers and Team.

Participants noted new and unexpected opportunities for connection and challenges, including the infeasibility of practicing some of the relationship-building skills taught in the PTL course given physical distancing requirements and increased workloads associated with the pandemic. Although some respondents emphasized hardships that the COVID-19 pandemic caused on maintaining contact with their peers/team, others outlined the opportunity to find new and meaningful ways to connect with their peers/team: (“I’m aware of the two-edged sword, that without the disruption of the existing patterns of planned and chance meetings in person, I might not be taking the time to connect in these different ways.”).

Question Two: “How Have You Adjusted Your Personal Life in Response to the Pandemic Crisis?”

Three themes were identified: accommodate adults working and children learning from home, looked for and found the positive, and continued to struggle.

Accommodate Adults Working and Children Learning from Home.

Participants focused on the needs of other adults and children working and learning from home, noting changes and additional roles. Respondents described these effects without positive or negative connotations (“The living room, dining room, front yard is now our school and gymnasium with my spouse serving the role of teacher, PE instructor, chef, guidance counselor.”).

Looked for and Found the Positive.

Participants observed positive aspects of their experiences with the changed routines, including slowing down and cherishing increased connections with loved ones while at home. Most respondents reported that working from home increased their time allocation to other projects, tasks, and responsibilities (“Decreased clinical load … leading to more time for writing, research, and planning.”).

Continue to Struggle.

This theme had two subthemes: relating to work and family, respectively. The first subtheme, home accommodations, described the challenges of maintaining work focus and productivity in a home environment with multiple demands and physical space constraints, making the privacy and quiet required for effective video meetings a challenge (“Online videoconferences for work present a particular challenge as they require quiet time and space, which are often not available.”). The second subtheme, changes to family life, presented the negative effects related to family members’ grief over a range of losses, including cancellation of college graduation ceremonies, isolation experienced by an aging parent in an assisted living facility with visits prohibited, and mourning the death of a family member (“Organizing and attending a memorial for a family member who passed away last week alone in a DC hospital from COVID-19.”). Even with all the hardships, participants still found it possible to look for the positive (“The pause has not been a bad thing. I have been able to slow down, work from home on academic work put off for years.”).

Question 3: “How Have You Used Leadership Skills Learned from Paths to Leadership?”

Four themes were identified: reflective practice, listening, holding, and reframing.

Reflective Practice.

Respondents emphasized using reflective practice learned in the PTL course to process their experiences and improve their effectiveness amidst the upheaval of the COVID-19 pandemic (“Clarifying goals in all areas of life and enhancing emotional intelligence to cope with stressful times.”).

Listening.

Participants highlighted their revitalization of the use of inquiry and active listening to connect with their team members and peers during a time of crisis (“As the toll of this pandemic is changing our lives, the least I can do is to listen attentively and try constantly to understand without having the urge to respond or interrupt.”).

Holding.

Respondents outlined acknowledgment of empathy through the framework of holding and containing their own and others’ experiences as an essential skill to support one another emotionally in a time of crisis:

Strengths of holding and containing during a crisis … specifically by taking time to reach out to others via email and telephone, encourage and support connection with each other, and identify and broadcast resources to help us all feel informed and that our concerns are being heard.

Reframing.

Participants described self-compassion and regulating their own emotions in a time of crisis. They highlighted use of this skill to support innovative responses to challenges, contributing to their abilities to be present and acknowledge the experiences of interprofessional team members during a crisis (“Knowing when to lead and when to follow, having ‘self-compassion,’ and getting myself ‘out of the basement’ at times of crisis.”)

Question 4: “What Lessons Have You Learned From Experiencing this Pandemic?”

Five themes were identified: leadership, human connection, be prepared, taking care of ourselves, and connecting to nature.

Leadership.

(“Strong leadership can set the tone for success.”). Participants noted the power of leaders to lead by example, learn, innovate, and model humanistic values and that it is okay to be learning while leading (“It is okay to frame our experience in a humanistic term in order to understand and accept while being gentle with oneself and with others.”).

Human Connection.

The power of human connection was exemplified by the sense that “we are all in this together”:

The incredible compassion, kindness, and hard work shown by humans from all different backgrounds and experiences is palpable. People and companies are coming together [despite physical distancing] to donate supplies, offer care and support for family, friends, and neighbors, the incredible support shown for our ‘essential workers.’

Being Prepared.

Participants spoke of the need to be prepared for the unpredictable together with the power of perseverance (“Double down on what’s most important: The loss of life, freedom, work, and the perception of ‘control’ during this time has been unprecedented. Let’s emerge more focused, and balanced, as we proceed into our new future.”).

Taking Care of Ourselves.

One participant noted, “we are all vulnerable,” and others spoke of being emotionally generous with ourselves and one another (“Take care of yourself and try to be patient with one another during this time.”).

Connecting with Nature.

Participants noted critical learnings related to the natural world emerging from pandemic experiences (“Last week sun and blooming flowers remind me of a new beautiful season upon us. The beauty in our nature buffers the issues and changes of the day.”).

Discussion

The timing of the university’s and academic center’s modified operations near the midpoint of this year’s PTL course provided a natural opportunity to observe the effects and adaptations of a group of faculty members who were all working to fine-tune their leadership abilities at various career stages. In an analogy, participants were called on to enact their newly learned leadership skills, much as a person attending a basic life support training would be called on to provide life support if someone in the class had a cardiac arrest. In the early pandemic chaos, the PTL course offered an opportunity to apply newly acquired leadership skills that might be used to address the current challenges, including relationship-building, positive organizational psychology, and reframing skills. Moreover, this course provided an opportunity to listen to our peers’ stories, experiences, and challenges, uncovering common themes that may be helpful to others. These faculty leaders’ reflections suggest that we might find connections and notice our relatedness to one another, regardless of our primary missions in this time of crisis. Although these themes were generated based on individual experiences, they can be broadly applicable for health care leaders.

Most of our participants have adjusted to COVID-19-related social, working, and family changes very well and have incorporated their newly learned leadership skills offered by the PTL course in their adjustment. Every theme identified from the lesson-learned prompt has been described previously as a fundamental aspect of effective interprofessional leadership and innovation (CatalystNEJM, 2020; Edmondson, 2013; Gino, 2019; Heath & Heath, 2010; Ibarra, 2015; Tan, 2012), and these themes are important now more than ever (Park et al., 2020). The respondents emphasized that learning is a life-long process. Learning is clearly a fundamental leadership skill, and being open to learning in a time of crisis through reflective practice and listening is consistent with past literature (Dean, 2020). In particular, PTL participants’ experiences of framing and holding, communication, and a strong emphasis on compassion and kindness, were acknowledged as critical leadership skills during the COVID-19 pandemic (Petriglieri, 2020).

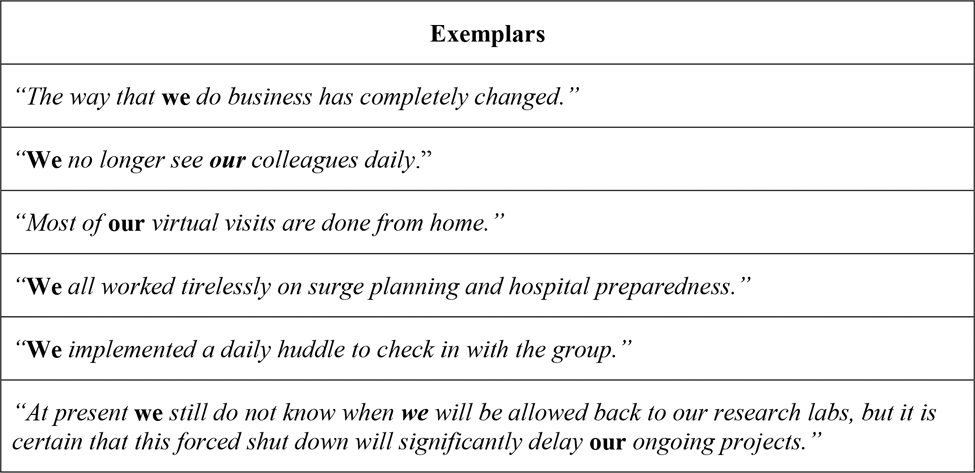

In summary, participants reported that being enrolled in the PTL course during the COVID-19 pandemic increased their awareness of their abilities and responsibilities to lead through this challenging change in their practices. Moreover, an unexpected discovery in the conventional content analysis emphasized the importance of interprofessional collaboration to the respondents. It was noted that even though the prompts were directed towards the individual responding (using terms like “you” and “your”), the responses often reflected the individual as part of a team (using words like “we” and “our”). Common exemplars of these responses are presented in Figure 1. The importance of interprofessional collaboration is highlighted by this finding especially considering the various health care disciplines of the participants; yet, they commonly responded with collective terminologies such as “we” and “our” across professions, outlining the point that we are all in this together as health care leaders (Park et al., 2020). We recommend further investigation into this finding to better understand the perspective around interprofessional collaboration relative to nurse leaders to facilitate this collaboration by removing barriers (Kneipp et at., 2014), especially during a time of crisis. Such collaboration among health care professionals supports safe, efficient, and high-quality patient care (Guck et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2020), and strengthens safety culture and communication for nurse leaders and other health care providers (Schmidt et al., 2021).

Figure 1:

Exemplars of Collective Pronouns Used by Respondents

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is that the participants were diverse faculty members from various departments, levels of leadership, and primary focus. Additionally, faculty members from the School of Nursing conducted this study (including the analysis and drafting of the manuscript), given the interprofessional nature of nursing research. Our inter- and multidisciplinary team of researchers are recognized for their expertise in their fields, and this qualitative study can be generalized to more broad disciplines, including nursing research. However, there are several limitations to this study. First, we offer the perspectives of a small sample of health care leaders with varied roles, making it hard to differentiate the leadership implications from the training program.

Nevertheless, our sample size is consistent with the minimum sample size of 12 recommended for qualitative research (Vasileiou et al., 2018). Second, although we might have preferred a more interactive method for data collection such as semistructured interviews, we chose an open-ended survey methodology to mitigate the time burden on participants given their status as active health care leaders during an ongoing pandemic. This factor may also have contributed to the small sample size. Third, these perspectives come from faculty within a single institution located in a city that experienced relatively lower initial proportions of COVID-19 cases than other cities. Rather than seeking to generalize our findings, we offer a rich local perspective on how an interprofessional group of learners experienced and responded to a novel challenge in the middle of their leadership course. These lessons can be used as guidance for future unforeseen crises.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought both hardships and opportunities to interprofessional faculty members enrolled in a leadership course within an academic health system. Beyond these hardships and opportunities, it seems that the COVID-19 pandemic in conjunction with the PTL course provided a unique opportunity to reevaluate and reflect on the leadership skills required to make a meaningful difference in one’s practice and/or institution during a time of crisis. Human connection is the foundation for effective leadership. Our PTL cohort experienced an unexpected opportunity to practice human connection during an acute disruption of typical patterns of personal, professional, and interprofessional relationships. Future leadership programs may share benefits from these lessons, using this cohort’s reflections to guide leadership strategies and better cope with challenges in the future. These lessons are particularly relevant to nursing leaders, given the interprofessional and independent nature of the field of nursing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

We would like to acknowledge the significant contributions of our late colleague Dr. Janice A. Vranka, a gifted scientist, educator and leader who collaborated fully on this article prior to her untimely death in 2021.

The authors would like to acknowledge the significant contributions of our late colleague Dr. Janice A. Vranka, a gifted scientist, educator, and leader who collaborated fully on this article prior to her untimely death in 2021.

Funding:

This project was supported by funding from the National Institute of Health (NIH) Office of Research on Women’s Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development K12HD043488 (Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health, BIRCWH) (Z. Zhang) and by Achievement Rewards for College Scientists (ARCS) Foundation (A. Eisen).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Conflicts of Interest: None

Ethical Conduct of Research: This study was reviewed by the university’s Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt (IRB #00020001).

This study was reviewed by the university’s institutional review board (IRB) and determined to be exempt (IRB #00020001).

Clinical Trial Registration: NA

Contributor Information

Asma A. Taha, School of Nursing, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Zhenzhen Zhang, Division of Oncological Sciences, Knight Cancer Institute, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Martha Driessnack, School of Nursing, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

James J. Huntzicker, Division of Management, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Aaron M. Eisen, School of Nursing, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Juliana Bernstein, Division of General Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Aiyin Chen, Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Ravi A. Chandra, Department of Radiation Medicine, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Karen Drake, Department of Otolaryngology, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Alice Fung, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Rand Ladkany, Division of Hospital Medicine, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Brenda LaVigne, Department of Vascular Surgery/Wound and Hyperbaric Medicine, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Rahel Nardos, Obstetrics, Gynecology & Women Health, School of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Christina Sayama, Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Larisa G. Tereshchenko, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Brittany Wilson, Division of Audiology/Vestibular Services/Cochlear Implants, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

Nicole A. Steckler, Division of Management, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, 97239.

References

- Bolman LG, & Deal TE (2021). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (7th ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE, Rochford K, & Taylor SN (2015). The role of the positive emotional attractor in vision and shared vision: Toward effective leadership, relationships, and engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 670. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CatalystNEJM. (2020, July 29). Lessons from CEOs: Health care leaders nationwide respond to the COVID-19 crisis. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 1. Retrieved from https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/CAT.20.0150 [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dean E (2020, May 12). How to use your COVID-19 experience for reflective practice. RCNI. Retrieved from https://rcni.com/nursing-standard/features/how-to-use-your-covid-19-experience-reflective-practice-160601

- Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Lahiri D, & Lavie CJ (2020). Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14, 779–788. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson A, Boyatzis R, De Smet A, & Schaninger B (2020, July 2). Psychological safety, emotional intelligence, and leadership in a time of flux. McKinsey Quarterly. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/psychological-safety-emotional-intelligence-and-leadership-in-a-time-of-flux

- Edmondson AC (2013). Teaming to innovate. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Forster BB, Patlas MN, & Lexa FJ (2020). Crisis leadership during and following COVID-19. Canadian Association of Radiologists, 71, 421–422. 10.1177/0846537120926752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SD (2008). Total leadership: Be a better leader, have a richer life. Harvard Business Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gino F (2019). Cracking the code of sustained collaboration. Harvard Business Review, 97, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Guck TP, Potthoff MR, Walters RW, Doll J, Greene MA, & DeFreece T (2019). Improved outcomes associated with interprofessional collaborative practice. Annals of Family Medicine, 17, S82. 10.1370/afm.2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatami H, Sjatil PE, & Sneader K (2020, May 28). COVID-19: The toughest leadership test. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/the-toughest-leadership-test

- Heath C, & Heath D (2010). Switch: How to change things when change is hard. Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra H (2015). Act like a leader, think like a leader. Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp SM, Gilleskie D, Sheely A, Schwartz T, Gilmore RM, & Atkinson D (2014). Nurse scientists overcoming challenges to lead transdisciplinary research teams. Nursing Outlook, 62, 352–361. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oroszi T (2018). A preliminary analysis of high-stakes decision-making for crisis leadership. Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning, 11, 335–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B, Steckler N, Ey S, Wiser AL, & DeVoe JE (2020, June 23). Co-creating a thriving human-centered health system in the post-COVID-19 era. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. Retrieved from https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/CAT.20.0247 [Google Scholar]

- Petriglieri G (2020, April 22). The psychology behind effective crisis leadership. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/04/the-psychology-behind-effective-crisis-leadership [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J, Gambashidze N, Manser T, Güß T, Klatthaar M, Neugebauer F, & Hammer A (2021). Does interprofessional team-training affect nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of safety culture and communication practices? Results of a pre-post survey study. BMC Health Services Research, 21, 341. 10.1186/s12913-021-06137-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingler-Nace A (2020). COVID-19: When leadership calls. Nurse Leader, 18, 202–203. 10.1016/j.mnl.2020.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckler NA (2019, July). Paths to leadership: Supporting emerging faculty leaders in making a meaningful difference [Podium presentation]. AAMC Group on Faculty Affairs (GFA)/ Group on Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS) National Professional Development Conference, Chicago, IL, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Steckler NA, & Huntzicker JJ (2015). Nurturing creative destruction: Bringing management mindsets and influence skillsets to healthcare. In Bradbury H (Ed.), SAGE handbook of action research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publishing. 10.4135/9781473921290.n76 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C-M (2012). Search inside yourself: The unexpected path to achieving success, happiness (and world peace). HarperOne. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, & Young T (2018). Characterizing and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 148. 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Corbett RW, Ray J, & Wei TL (2020). A culture of caring: The essence of healthcare interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34, 324–331. 10.1080/13561820.2019.1641476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.