Abstract

Purpose

The incidence of inguinal hernia is higher in elderly because of aging-related diseases like prostatism, bronchitis, collagen laxity. A conservative management is common in elderly to reduce surgery-related risks, however watchful waiting can expose to obstruction and strangulation. The aim of the present study was to assess the impact of emergency surgery in a large series of elderly with complicated groin hernia and to identify the independent risk factors for postoperative morbidity and mortality. The predictive performance of prognostic risk scores has been also assessed.

Methods

This is a prospective observational study carried out between January 2017 and June 2018 in elderly patients who underwent emergency surgery for complicated hernia in 38 Italian hospitals. Pre-operative, surgical and postoperative data were recorded for each patient. ASA score, Charlson’s comorbidity index, P-POSSUM and CR-POSSUM were assessed.

Results

259 patients were recruited, mean age was 80 years. A direct repair without mesh was performed in 62 (23.9%) patients. Explorative laparotomy was performed in 56 (21.6%) patients and bowel resection was necessary in 44 (17%). Mortality occurred in seven (2.8%) patients. Fifty-five (21.2%) patients developed complications, 12 of whom had a major one. At univariate and multivariate analyses, Charlson’s comorbidity index ≥ 6, altered mental status, and need for laparotomy were associated with major complications and mortality

Conclusion

Emergency surgery for complicated hernia is burdened by high morbidity and mortality in elderly patients. Preoperative comorbidity played a pivotal role in predicting complications and mortality and therefore Charlson’s comorbidity index could be adopted to select patients for elective operation

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10029-020-02269-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Groin hernia, Incarcerated hernia, Elderly, Postoperative complications, Emergency surgery, Charlson’s comorbidity index

Introduction

Inguinal and femoral hernias are very common clinical situations worldwide with estimated prevalence of 27–43% in men and 3–6% in women [1]. Despite groin hernia is widespread in all age groups of population, its incidence is higher in elderly [2]. Conditions frequently associated to advanced age, such as constipation, prostatism, frequent coughing due to respiratory diseases and weakness of the abdominal wall, play an important role in the development and evolution of abdominal wall hernias [2, 3].

Groin hernias can progress to incarceration and strangulation which constitute a common surgical emergency. The estimated risk of an inguinal hernia becoming incarcerated is 4.5% after 2 years and the complication risk is higher in femoral hernia with a 22% cumulative probability at 3 months and 45% at 21 months [4].

Regardless of age and frailty European Hernia Society Guidelines recommend surgery in case of symptomatic inguinal hernia; whereas if patients do not complain of symptoms the indication to surgical repair is debated, being a watchful approach an option [3]. Although elective surgery repair is performed safely with minimal morbidity [5, 6] conservative treatment is sometimes preferred in elderly due to comorbidities. On the other hand, the natural history of a conservatively managed groin hernia is size increasing due to continuous action of intra-abdominal pressure and progressive abdominal wall laxity [3]. This exposes patients to an increasing risk of bowel obstruction and strangulation requiring emergency surgery with consequent risk of laparotomy and bowel resection [7]. The balance between the risks of elective surgery versus the risks of a watchful approach is still a matter of debate in absence of specific recommendations for elderly.

The aim of the present study was to assess the impact of emergency surgery in a large series of elderly patients with complicated groin hernia and to identify independent risk factors for postoperative morbidity and mortality. The predictive performance of prognostic risk scores has also been assessed.

Methods

The present study analyzed data from the Frailty and Emergency Surgery Study (FRAILESEL) database [8]; FRAILESEL is a prospective observational project that collected data in consecutive elderly patients who underwent emergency surgery in 38 Italian hospitals. The Study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sapienza University of Rome and of all participating centers and was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02825082). All patients who underwent emergency surgery for incarcerated inguinal or femoral hernia between January 2017 and June 2018 were included in the present study. For each patient the following data were recorded: age, sex, BMI, comorbidities, American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) score, preoperative hemodynamic status, type of incarcerated hernia (inguinal or femoral), surgical technique, need for explorative laparotomy and bowel resection. For each patient, the Charlson’s comorbidity index [9, 10], the predicted morbidity and mortality risks according to the P-POSSUM and the CR-POSSUM models [11, 12] were also calculated.

All postoperative complications and reoperations that occurred during hospitalization or within 30 days after discharge were registered and graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [13].

Continuous variables were expressed as mean (SD) or median (IQR) as appropriate; categorical data were showed as proportion and percentages. Five different variables were selected as outcomes: explorative laparotomy, abdominal viscera resection, complications, major complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ IIIb), and mortality. Univariate analysis was carried out with the chi square test and Mann–Whitney U test; variables significantly associated with the outcomes were inserted in a multivariate model with the logistic regression method; multivariate analysis was not computed in case of number of events < 10.The ASA scores and the Charlson’s comorbidity index were analyzed with the ROC curves method in order to choose a cut-off for complications, major complications and mortality. ASA score (both as categorical and with the cut-off chosen with the ROC method), the Charlson’s comorbidity index (both as continuous, categorical the cut-off chosen with the ROC method), the predicted risk of morbidity and mortality with the P-POSSUM and CR-POSSUM models and the length of stay were compared among patients with or without the selected outcomes (morbidity and mortality) with the appropriate test. Statistics were calculated with SPSS 25 IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

A total of 259 consecutive patients operated for complicated inguinal or femoral hernia were included in the analysis.

Table 1 reports patients’ characteristics in detail. Mean age was 80(± 8) years and 58% patients were men. Common comorbidities were hypertension (65%), chronic heart disease (28%), arrhythmia (34%), and COPD (18%) while 20% of patients were in therapy with oral anticoagulants. Patients with inguinal hernia were similar to those with femoral hernia in terms of comorbidity and pre-operative characteristics; as expected female sex was more common in femoral hernia (84% vs. 23%, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 259 | |||

| Age | 79.70 (8.37) | 79 (73–87) | ||

| Age class | ||||

| 65–70 | 41 | 15.1% | ||

| 71–75 | 49 | 18.3% | ||

| 76–80 | 51 | 19.7% | ||

| 81–85 | 39 | 15.1% | ||

| 86–90 | 51 | 19.7% | ||

| > 90 | 28 | 10.8% | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 109 | 42.1% | ||

| Male | 150 | 57.9% | ||

| BMI | 25.36 (5.67) | 24.74 (22–27) | ||

| Mental status impairment | 14 | 6.3% | ||

| Hypotension (SBP < 90) | 3 | 1.2% | ||

| Tachycardia (HR > 100) | 14 | 5.4% | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Atrial Fibrillation/arrhythmia | 96 | 37.1% | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 8 | 3.1% | ||

| Chronic heart disease | 73 | 28.2% | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 168 | 64.9% | ||

| Peripheral artery disease | 37 | 14.3% | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 38 | 14.7% | ||

| Oral Anticoagulants | 52 | 20.1% | ||

| COPD | 48 | 18.5% | ||

| Metastatic Cancer | 9 | 3.5% | ||

| Cancer without metastasis | 23 | 8.9% | ||

| Leukemia/lymphoma | 7 | 2.7% | ||

| Hepatic disease | 10 | 3.9% | ||

| Kidney disease | 22 | 8.5% | ||

| Diabetes | 32 | 16.2% | ||

| Peptic ulcer | 6 | 2.3% | ||

| Connective tissue disease | 10 | 3.9% | ||

| Steroids/immunosuppressive | 14 | 5.4% | ||

| Emiplegia | 10 | 3.9% | ||

| Demenza | 27 | 10.4% | ||

| ASA score | ||||

| 1 | 12 | 4.7% | ||

| 2 | 88 | 34.8% | ||

| 3 | 132 | 52.2% | ||

| 4 | 20 | 7.9% | ||

| 5 | 1 | 0.4% | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 4.97 (2.28) | 4 (3–6) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| < 6 | 176 | 68% | ||

| ≥ 6 | 83 | 32% | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| 0–1 | 0 | 0% | ||

| 2–3 | 71 | 27% | ||

| 4–5 | 105 | 40.5% | ||

| 6–7 | 46 | 17.8% | ||

| 8–9 | 28 | 10.8% | ||

| 10–11 | 5 | 1.9% | ||

| 12–13 | 2 | 0.8% | ||

| 14–15 | 1 | 0.4% | ||

| 16–17 | 1 | 0.4% | ||

| Predicted mortality risk (PPOSSUM) | 7.81 (12.46) | 3.60 (1.5–8.1) | ||

| Predicted morbidity risk (PPOSSUM) | 50.68 (24.11) | 49 (29–71) | ||

| Predicted mortality risk (CR-POSSUM) | 6.88 (7.34) | 5.10 (1.9–9) | ||

Table 2 shows surgical data and outcomes. One hundred and eighty (69.5%) patients were operated for inguinal hernia and 79 (30.5%) for femoral hernia. Laparoscopic surgery was carried out in 10 (12.66%) patients. A mesh repair was performed in 91% of patients with inguinal hernia and in 41% with femoral hernia. At univariate analysis, factors related to the mesh placement were increasing BMI (as a continuous variable) (OR = 1.147; CI 95% = 1.040–1.264); male gender (OR = 5.501; CI 95% = 2.922–10.35); femoral hernia (OR = 0.062; CI 95% = 0.031–0.124), need for explorative laparotomy (OR = 0.379; CI 95% = 0.200–0.718) and bowel resection (OR = 0.230; CI 95% = 0.119–0.446). At multivariate analysis only femoral hernia maintained an independent association with mesh (OR = 0.64; CI 95% = 0.021–0.199).

Table 2.

Surgery data and outcomes

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | n (%) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to surgery (days) | 0.58 (1.49) | 0 (0–1) | ||

| Kind of hernia | ||||

| Inguinal | 180 | 69.11% | ||

| Femoral | 79 | 30.12% | ||

| Inguinal hernia | ||||

| Direct repair | 15 | 8.33% | ||

| Mesh | 165 | 91.67% | ||

| Femoral hernia | ||||

| Direct repair | 47 | 59.49% | ||

| Mesh | 32 | 40.51% | ||

| Laparoscopic repair | 10 | 12.66% | ||

| Explorative laparotomy/laparoscopy | 56 | 21.62% | ||

| Intestinal resection | ||||

| No | 215 | 83.01% | ||

| Colon | 2 | 0.77% | ||

| Ileum | 41 | 15.83% | ||

| Ileum-cecum | 1 | 0.39% | ||

| Length of stay | 5.17 (4.02) | 4.00 (2.00–7.00) | ||

| Reintervention | 3 | 1.16% | ||

| Major complications | 12 | 4.63% | ||

| Complications | 55 | 21.24% | ||

| Perforation | 2 | 0.77% | ||

| Occlusion | 5 | 1.93% | ||

| Pneumonia | 8 | 3.09% | ||

| Acute renal failure | 4 | 1.54% | ||

| Bleeding | 5 | 1.93% | ||

| Stroke | 2 | 0.77% | ||

| Acute myocardial infarction/heart failure | 3 | 1.16% | ||

| Arrhythmia | 5 | 1.93% | ||

| SSI | 6 | 2.32% | ||

| Mortality | 7 | 2.70% | ||

An explorative laparotomy was necessary in 56 (21.6%) patients and 44 (17.0%) of them had a bowel resection. At multivariate analysis, significant risk factors were ASA score > 2 for laparotomy and femoral hernia for bowel resection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factor associated to laparotomy and resection

| laparotomy | Resection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) univariate | p | OR (95% CI) multivariate | p | OR (95% CI) univariate | p | OR (95% CI) multivariate | p | |

| Age | 1.006 (0.971–1.042) | 0.736 | 0.984 (0.948–1.022) | 0.399 | ||||

| BMI | 0.974 (0.906–1.048) | 0.482 | 0.941 (0.859–1.031) | 0.193 | ||||

| Male sex | 0.606 (0.334–1.098) | 0.097 | 0.784 (0.42–1.464) | 0.445 | ||||

| ASA ≥ 3 | 3.16 (1.57–6.33) | 0.001 | 1.876 (1.165–3.021) | 0.01 | 1.94 (0.991–3.831) | 0.051 | ||

| Charlson ≥ 6 | 1.66 (0.901–3.065) | 0.102 | 1.44 (0.758–2.754) | 0.262 | ||||

| Femoral Hernia (inguinal ref) | 1.830 (0.989–3.384) | 0.052 | 2.187 (1.153–4.147) | 0.015 | 2.275 (1.190–4.348) | 0.013 | ||

| Arrhythmia | 1.241 (0.678–2.227) | 0.483 | 1.216 (0.644–2.296) | 0.546 | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 1.216 (0.239–6.196) | 0.814 | 1.447 (0.283–7.395) | 0.656 | ||||

| Chronic heart disease | 3.882 (1.082–13.925) | 0.026 | 2.260 (0.577–8.846) | 0.242 | 3.022 (0.819–11.153) | 0.083 | ||

| Hypertension | 0.858 (0.464–1.586) | 0.625 | 0.652 (0.346–1.231) | 0.186 | ||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.359 (0.616–2.999) | 0.447 | 0.776 (0.305–1.974) | 0.594 | ||||

| Oral anticoagulants | 1.11 (0.538–2.297) | 0.776 | 1.193 (0.562–2.533) | 0.645 | ||||

| Chronic lung diseases | 1.657 (0.816–3.364) | 0.159 | 1.568 (0.745–3.279) | 0.233 | ||||

| Metastatic solid tumors | 1.858 (0.45–7.679) | 0.385 | 3.644 (1.041–14.112) | 0.047 | 4.008 (1.029–16.24) | 0.045 | ||

| Non-metastatic solid tumors | 0.745 (0.243–2.286) | 0.606 | 0.62 (0.177–2.1734) | 0.451 | ||||

| Liver disease | 0.903 (0.186–4.376) | 0.899 | 1.891 (0.471–7.592) | 0.362 | ||||

| Kidney disease | 1.073 (0.378–3.047) | 0.895 | 0.948 (0.306–2.938) | 0.926 | ||||

| Diabetes | 0.440 (0.164–1.178) | 0.095 | 0.402 (0.136–1.186) | 0.089 | ||||

| Steroids/immunosoppressors | 1.485 (0.447–4.926) | 0.516 | 2.538 (0.811–7.942) | 0.099 | ||||

| Dementia | 2.857 (1.241–6.577) | 0.011 | 2.051 (0.841–5.001) | 0.114 | 1.961 (0.804–4.787) | 0.133 | ||

| Leukemia/lymphoma | 0.597 (0.07–5.064) | 0.633 | 1.745 (0.328–9.270) | 0.509 | ||||

Bold indicate depicted significative results

Post-operative outcomes are reported in Table 2. Overall morbidity was 21.2%. Major complications occurred in 12 (4.6%) patients and mortality in seven (2.8%) patients. Three patients died for sepsis, one for heart failure, acute cardiac ischemia, stroke, and hemorrhage. Mean length of stay was significantly longer in patients with complications than in uneventful (8.3 vs. 4.3, p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prognostic score assessment and distribution among patients

| Complications | p-value | Major complications | p-value | Mortality | p-value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Complicated | None | Complicated | Alive | Dead | ||||||||||

| N/mean | %/(SD) | N/mean | %/(SD) | N/mean | %/(SD) | N/mean | %/(SD) | N/mean | %/(SD) | N/mean | %/(SD) | ||||

| ASA score | |||||||||||||||

| Mean | 2.59 | 0.70 | 2.84 | 0.74 | 0.024 | 2.62 | 0.69 | 3.08 | 1.00 | 0.024 | 2.61 | 0.69 | 3.57 | 0.98 | < 0.001 |

| ASA score | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 11 | 91.7% | 1 | 8.3% | 0.105 | 12 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | < 0.001 | 12 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 72 | 81.8% | 16 | 18.2% | 84 | 95.5% | 4 | 4.5% | 85 | 98.8% | 1 | 1.2% | |||

| 3 | 102 | 77.3% | 30 | 22.7% | 128 | 97.0% | 4 | 3.0% | 126 | 98.4% | 2 | 1.6% | |||

| 4 | 13 | 65.0% | 7 | 35.0% | 17 | 85.0% | 3 | 15.0% | 16 | 84.2% | 3 | 15.8% | |||

| 5 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | |||

| ASA score | |||||||||||||||

| < 3 | 89 | 84.0% | 17 | 16.0% | 0.089 | 102 | 96.2% | 4 | 3.8% | 0.584 | 103 | 99.0% | 1 | 1.0% | 0.141 |

| ≥ 3 | 115 | 75.2% | 38 | 24.8% | 145 | 94.8% | 8 | 5.2% | 142 | 95.9% | 6 | 4.1% | |||

| CHARLSON | |||||||||||||||

| Mean | 4.78 | 2.05 | 5.76 | 2.76 | 0.004 | 4.91 | 2.11 | 6.67 | 3.98 | 0.008 | 4.92 | 2.11 | 8.86 | 3.85 | < 0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||||||||||||||

| < 6 | 146 | 83.0% | 30 | 17.0% | 0.016 | 171 | 97.2% | 5 | 2.8% | 0.046 | 169 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | < 0,001 |

| ≥ 6 | 58 | 69.9% | 25 | 30.1% | 76 | 91.6% | 7 | 8.4% | 76 | 91.6% | 7 | 8.4% | |||

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||||||||||||||

| 1–2-Jan | 60 | 84.5% | 11 | 15.5% | 0.153 | 69 | 97.2% | 2 | 2.8% | < 0.001 | 67 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | < 0.001 |

| 4–5-Apr | 86 | 81.9% | 19 | 18.1% | 102 | 97.1% | 3 | 2.9% | 102 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |||

| 6–7-Jun | 34 | 73.9% | 12 | 26.1% | 43 | 93.5% | 3 | 6.5% | 43 | 93.5% | 3 | 6.5% | |||

| 8–9-Aug | 19 | 67.9% | 9 | 32.1% | 26 | 92.9% | 2 | 7.1% | 26 | 92.9% | 2 | 7.1% | |||

| 10–11-Oct | 3 | 60.0% | 2 | 40.0% | 4 | 80.0% | 1 | 20.0% | 4 | 80.0% | 1 | 20.0% | |||

| 12–13-Dec | 1 | 50.0% | 1 | 50.0% | 2 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |||

| 14–15 | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |||

| 16–17 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | |||

| LOS | 4.30 | 3.25 | 8.38 | 4.88 | < 0.001 | 4.93 | 3.63 | 10.00 | 7.54 | < 0.001 | 5.00 | 3.80 | 11.57 | 7.18 | < 0.001 |

| Predicted mortality risk (PPOSSUM) (mean) | 7.18 | 10.91 | 30.70 | 33.30 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Predicted morbidity risk (PPOSSUM) (mean) | 46.97 | 22.41 | 64.43 | 25.41 | < 0.001 | 49.98 | 23.85 | 64.96 | 26.01 | 0.035 | |||||

| Predicted mortality risk (CR-POSSUM) (mean) | 6.63 | 7.00 | 17.07 | 13.74 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

The multivariate analysis demonstrated that preoperative conditions, such as heart and lung dysfunctions and Charlson’s comorbidity index ≥ 6, were independently associated with major complications and mortality (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for complications and mortality

| Complication | Major complication | Mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) univariate | p | OR (95% CI) multivariate | p | OR (95%CI) univariate | p | OR (95%CI) univariate | p | |

| Age | 1.010 (0.974–1.046) | 0.594 | 0.959 (0.892–1.031) | 0.256 | 1.019 (0.931–1.115) | 0.69 | ||

| BMI | 0.968 (0.902–1.032) | 0.364 | 0.924 (0.784–1.089) | 0.347 | 0.842 (0.687–1.031) | 0.096 | ||

| hypotension | 7.843 (0.678–88.20) | 0.051 | 53.74 (4.45–649) | < 0.001 | 120 (8.95–1600) | < 0.001 | ||

| Tachycardia | 4.217 (1.41–12.74) | 0.006 | 2.889 (0.673–12.40) | 0.154 | 7.909 (1.84–33.98) | 0.001 | 23.1 (4.13–129) | < 0.001 |

| Mental impairment | 3.837 (1.277–11.529) | 0.011 | 2.502 (0.626–9.993) | 0.194 | 10 (2.57–38.88) | < 0.001 | 26.4 (5.192–134.226) | < 0.001 |

| Male Sex | 0.635 (0.349–1.155) | 0.135 | 1.018 (0.314–3.297) | 0.976 | 1.875 (0.357–9.854) | 0.451 | ||

| ASA ≥ 3 | 1.730 (0.916–3.265) | 0.089 | 1.407 (0.413–4.797) | 0.584 | 4.352 (0.516–36.70) | 0.141 | ||

| Charlson ≥ 6 | 2.09 (1.138–3.867) | 0.016 | 1.105 (0.624–1.956) | 0.732 | 3.150 (1.03–10.24) | 0.046 | – | < 0.001 |

| Crural hernia | 1.404 (0.750–2.630) | 0.287 | 1.147 (0.335–3.925) | 0.827 | 0.889 (0.169–4.687) | 0.89 | ||

| Laparotomy | 4.161 (2.166–7.995) | < 0.001 | 6.607 (2.905–15.03) | < 0.001 | 5.657 (1.722–18.586) | 0.002 | 5.2 (1.127–23.987) | 0.02 |

| Prosthesis | 0.795 (0.433–1.46) | 0.46 | 1.008 (0.285–3.571) | 0.99 | 1.034 (0.205–5.223) | 0.968 | ||

| Bowel resection | 3.448 (1.755–6.776) | < 0.001 | 0.721 (0.193–3.165) | 0.728 | 6.833 (2.069–22.567) | < 0.001 | 6.264 (1.353–29.005) | 0.008 |

| Arrhythmia | 2.074 (1.134–3.792) | 0.017 | 2.813 (1.317–6.008) | 0.008 | 1.224 (.0378–3.971) | 0.735 | 1.247 (0.273–5.698) | 0.775 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2.296 (0.531–9.922) | 0.253 | 8.003 (1.437–44.897) | 0.005 | 15.933 (2.558–99.23) | < 0.001 | ||

| Chronic heart disease | 2.588 (0.704–9.516) | 0.139 | 11.429 (2.531–51.597) | < 0.001 | 11.850 (1.898–70.605) | 0.001 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.739 (0.890–3.397) | 0.103 | 2.767 (0.593–12.91) | 0.178 | 3.188 (0.378–26.91) | 0.261 | ||

| cerebrovascular disease | 1.181 (0.522–2.668) | 0.689 | 1.172 (0.247–5.572) | 0.841 | 2.322 (0.434–12.42) | 0.312 | ||

| Oral anticoagulants | 1.915 (0.966–3.795) | 0.06 | 3.04 (0.924–9.999) | 0.056 | 5.617 (1.216–25.95) | 0.014 | ||

| COPD | 2.205 (1.102–4.412) | 0.023 | 2.505 (1.024–6.126) | 0.044 | 3.389 (1.027–11.182) | 0.035 | 3.426 (0.74–15.855) | 0.095 |

| Metastatic solid tumors | 1.904 (0.461–7.87) | 0.366 | 2.716 (0.312–23.666) | 0.347 | 4.938 (0.53–45.972) | 0.121 | ||

| Non-metastatic solid tumors | 1.347 (0.504–3.598) | 0.551 | 2.152 (0.442–10.478) | 0.332 | 4.5 (0.82–24.692) | 0.059 | ||

| Liver disease | 0.401 (0.05–3.237) | 0.376 | – | 0.477 | – | 0.606 | ||

| Kidney disease | 1.838 (0.71–4.758) | 0.205 | 2.27 (0.465–11.082) | 0.298 | 4.5 (0.82–24.692) | 0.59 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.868 (0.895–3.898) | 0.093 | 1.778 (0.461–6.862) | 0.398 | 4.086 (0.879–18.98) | 0.053 | ||

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 3 (1.004–9.047) | 0.042 | 3.684 (0.941–14.42) | 0.061 | 1.636 (0.196–3.659) | 0.646 | 2.974 (0.333–26.562) | 0.306 |

| Dementia | 2.022 (0.853–4.791) | 0.104 | 4.87 (1.361–17.421) | 0.008 | 13.515 (2.841–64.297) | < 0.001 | ||

| Leukemia/lymphoma | 0.611 (0.072–5.185) | 0.649 | 3.652 (0.404–33.006) | 0.218 | 6.639 (0.688–64.05) | 0.06 | ||

Prognostic scores

The predicted risk according to the P-POSSUM model was 50% (± 24) for morbidity and 7.81% (± 12) for mortality. The CR-POSSUM model prediction mortality was 6.88% (± 7).

With the ROC curves method were individuated two cut-off for the ASA score (cut-off three) and Charlson’s comorbidity index (cut-off six) (see supplementary materials).

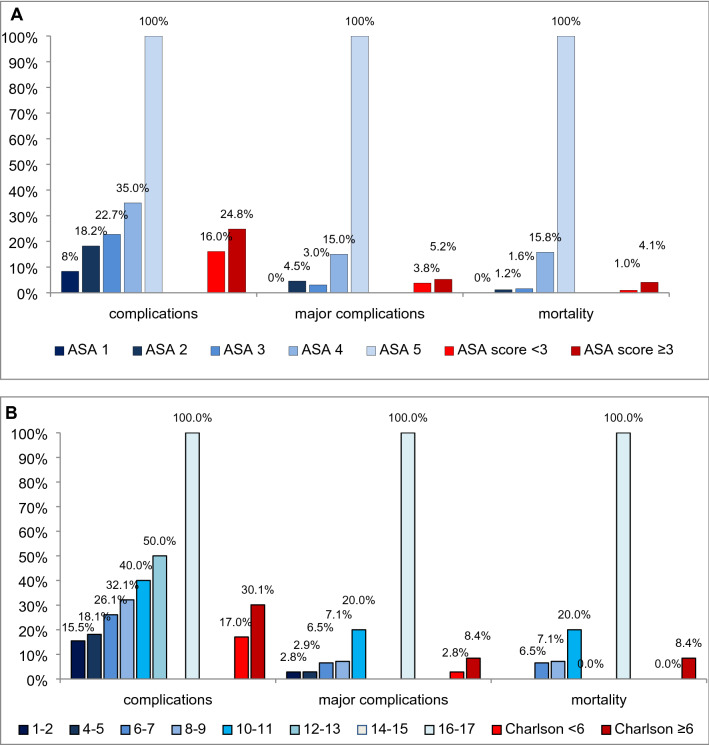

Major morbidity was 5.2%, in patients with ASA score ≥ 3 compared with 3.8% in patients with ASA < 3 (p = 0.584). In patients with Charlson’s comorbidity index ≥ 6 major morbidity was 8.4% compared with 2.8% in patients with index < 6 (p < 0.045). Mortality with ASA score ≥ 3 was 4.1, compared with 1% in patients with ASA < 3 (p = 0.141). In patients with Charlson’s comorbidity index ≥ 6 mortality was 8% compared with 0% in patients with index < 6 (p < 0.001). Results are shown in detail in Table 4 and Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

a complications, major complications and mortality rates among ASA score (a) and Charlson’s comorbidity index (b) classes

Discussion

The present study shows that emergency surgery for complicated hernia is burdened by high morbidity and mortality in elderly patients. Femoral hernia was associated with a higher risk of laparotomy and bowel resection. Heart and lung dysfunction, impaired mental status, and oral anticoagulant therapy were correlated to postoperative complications and mortality.

In current practice, elderly patients presenting with asymptomatic groin hernia are often managed conservatively to avoid the surgery-related risk of complications. A watchful waiting is recognized as an acceptable option for patients with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias [14, 15]. On the other hand, an incarcerated hernia can be sometimes difficult to identify by physical examination [16] and a delayed diagnosis could significantly increase the risk of strangulation. Incarceration and even more strangulation seldom occur, but require mandatory emergency surgery which is burdened by higher mortality and morbidity in elderly when compared to younger patients [17, 18]. In the emergency setting general anesthesia is usually preferred, whereas local or loco-regional anesthesia is the first option for elective hernia repair, especially in elderly patients with severe comorbidities [19].

In the present study the overall postoperative mortality (2.8%) was substantially higher than those reported after elective hernia repair in elderly [20]. In the subgroup of patients who had laparotomy and bowel resection mortality was 7.14%, consistent with previous series reporting a mortality increase up to 20% in case of ischemic herniated bowel resection [20–22]. Overall morbidity was 21% and major complication rate was 5%, both aligning with the existing literature on emergency surgery for complicated hernia [23], but much higher when compared to elective surgery [24].

At multivariate analysis, impaired mental status, heart and lung dysfunctions, and oral anticoagulant therapy were independently associated to major complications and mortality. Noteworthy, diabetes was not associated with morbidity or mortality in our cohort of patients. Usually, the presence of comorbidities advises physicians to prefer a watchful approach. Despite the present study cannot demonstrate the superiority of an operative approach to groin hernia due to the lack of a control population the indication to perform an elective procedure should be carefully tailored, balancing the risk of hernia incarceration and the risk of postoperative complications, in case of emergency surgery. A particular attention should be reserved to patients with oral anticoagulants that can be safely stopped in proper time in case of elective surgery, but not in emergency setting.

To predict surgical risk in patients undergoing emergency surgery for incarcerated/strangulated groin hernia some common preoperative score have been tested. ASA score and above all Charlson’s comorbidity index allowed an easy and rapid stratification of patients at high risk for morbidity and mortality. Conversely, P-POSSUM and CR-POSSUM which has been specifically validated for colorectal and major surgery, failed to predict morbidity and mortality, with a predicted risk overestimation. Therefore, ASA score and Charlson’s comorbidity index could be adopted as valid tools for risk stratification in elderly to select candidates for elective hernia repair.

In patients undergoing emergency surgery, the use of mesh to repair hernia is still an open issue because prosthesis could increase the infectious risk [25]. However, in accordance with the EHS guidelines [3], a direct repair without mesh brings a greater risk of recurrence with possible need of redo surgery. According to WSES guidelines [16] a mesh should be used in clean and clean contaminated (CDC class I and II) [13] emergency setting, while the use of mesh should be discouraged in dirty/contaminated surgery which is burdened by an infection rate up to 38% following bowel resection [26]. In the present study the only independent factor related to direct repair was femoral hernia. An high proportion of patients with femoral hernia in fact did not receive mesh positioning (59.5%), exposing them to the risk of recurrence; on the contrary a great proportion of patients operated for inguinal hernia had the positioning of a mesh, despite the presence of strangulated/incarcerated viscera and the consequent risk of infection. In our series of elderly patients factors associated with the non-positioning of mesh were explorative laparotomy and bowel resection, both indicating the presence of a contaminated surgical field. Moreover also the age could have played an important role: the lower life expectation of elderly could have mitigated the risk of recurrence linked to the direct repair.

The observational multicentre cohort design without a control population to compare is a limitation of the present study, therefore no clear recommendations could be derived from the present paper; moreover the study was not originally designed specifically for groin hernia and therefore some important information are missing like the timeframe between incarceration and presentation in hospital. However, the prospective data collection and a priori definition of criteria to identify postoperative complications might mitigate this limitation. Moreover, a multicentre study allows better generalization of results than single centre, while the large series of patients allowed excluding confounders by multiple logistic analyses.

In conclusion, emergency surgery for complicated hernia is burdened by high morbidity and mortality in elderly patients. Femoral hernia was associated with a higher risk of laparotomy and bowel resection. Since preoperative comorbidity played a pivotal role in predicting complications and mortality, Charlson’s comorbidity index should be adopted as a valid tool for evaluate and select patients for elective operation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano - Bicocca within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. List of Elderly Risk Assessment and Surgical Outcome (ERASO) Collaborative Study Group endorsed by SICUT, ACOI, SICG, SICE, and Italian Chapter of WSES: F. Agresta, G. Alemanno, G. Anania, M. Antropoli, G. Argenio, J. Atzeni, N. Avenia, A. Azzinnaro, G. Baldazzi, G. Balducci, G. Barbera, G. Bellanova, C. Bergamini, L. Bersigotti, PP. Bianchi, C. Bombardini, G. Borzellino, S. Bozzo, G. Brachini, GM. Buonanno, T. Canini, S. Cardella, G. Carrara, D. Cassini, M. Castriconi, G. Ceccarelli, D. Celi, M. Ceresoli, M. Chiappetta, M. Chiarugi, N. Cillara, F. Cimino, L. Cobuccio, G. Cocorullo, E. Colangelo, G. Costa, A. Crucitti, P. DallaCaneva, M. De Luca, A. de Manzoni Garberini, C. De Nisco, M. De Prizio, A. De Sol, A. Dibella, T. Falcioni, N. Falco, C. Farina, E. Finotti, T. Fontana, G. Francioni, P. Fransvea, B. Frezza, G. Garbarino, G. Garulli, M. Genna, S. Giannessi, A. Gioffrè, A. Giordano, D. Gozzo, S. Grimaldi, G. Gulotta, V. Iacopini, T. Iarussi, G. Laracca, E. Laterza, A. Leonardi, L. Lepre, L. Lorenzon, G. Luridiana, A. Malagnino, G. Mar, P. Marini, R. Marzaioli, G. Massa, V. Mecarelli, P. Mercantini, A. Mingoli, G. Nigri, S. Occhionorelli, N. Paderno, GM. Palini, D. Paradies, M. Paroli, F. Perrone, N. Petrucciani, L. Petruzzelli, A. Pezzolla, D. Piazza, V. Piazza, M. Piccoli, A. Pisanu, M. Podda, G. Poillucci, R. Porfidia, G. Rossi, P. Ruscelli, A. Spagnoli, R. Sulis, D. Tartaglia, C. Tranà, A. Travaglino, P. Tomaiuolo, A. Valeri, G. Vasquez, M. Zago, E. Zanoni.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Data are available on request to the corresponding author.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The protocol of the present study was approved by the ethical committee of the Sapienza University, Rome, Italy (Prot. n. 231 SA_2016 del 12.12.2016).

Consent to participate

All the patients approved to participate to the study signing a specific form after careful information.

Consent for publication

All the patients approved the publication of the study results.

Footnotes

The members of “The ERASO Study Group” are listed in acknowledgements.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

M. Ceresoli, Email: Marco.ceresoli@libero.it

List of Elderly Risk Assessment and Surgical Outcome (ERASO) Collaborative Study Group endorsed by SICUT, ACOI, SICG, SICE, and Italian Chapter of WSES:

F. Agresta, G. Alemanno, G. Anania, M. Antropoli, G. Argenio, J. Atzeni, N. Avenia, A. Azzinnaro, G. Baldazzi, G. Balducci, G. Barbera, G. Bellanova, C. Bergamini, L. Bersigotti, P. P. Bianchi, C. Bombardini, G. Borzellino, S. Bozzo, G. Brachini, G. M. Buonanno, T. Canini, S. Cardella, G. Carrara, D. Cassini, M. Castriconi, G. Ceccarelli, D. Celi, M. Ceresoli, M. Chiappetta, M. Chiarugi, N. Cillara, F. Cimino, L. Cobuccio, G. Cocorullo, E. Colangelo, G. Costa, A. Crucitti, P. DallaCaneva, M. Luca, A. de Manzoni Garberini, C. De Nisco, M. De Prizio, A. De Sol, A. Dibella, T. Falcioni, N. Falco, C. Farina, E. Finotti, T. Fontana, G. Francioni, P. Fransvea, B. Frezza, G. Garbarino, G. Garulli, M. Genna, S. Giannessi, A. Gioffrè, A. Giordano, D. Gozzo, S. Grimaldi, G. Gulotta, V. Iacopini, T. Iarussi, G. Laracca, E. Laterza, A. Leonardi, L. Lepre, L. Lorenzon, G. Luridiana, A. Malagnino, G. Mar, P. Marini, R. Marzaioli, G. Massa, V. Mecarelli, P. Mercantini, A. Mingoli, G. Nigri, S. Occhionorelli, N. Paderno, G. M. Palini, D. Paradies, M. Paroli, F. Perrone, N. Petrucciani, L. Petruzzelli, A. Pezzolla, D. Piazza, V. Piazza, M. Piccoli, A. Pisanu, M. Podda, G. Poillucci, R. Porfidia, G. Rossi, P. Ruscelli, A. Spagnoli, R. Sulis, D. Tartaglia, C. Tranà, A. Travaglino, P. Tomaiuolo, A. Valeri, G. Vasquez, M. Zago, and E. Zanoni

References

- 1.HerniaSurge Group International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018;22:1–165. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compagna R, Rossi R, Fappiano F, et al. Emergency groin hernia repair: implications in elderly. BMC Surg. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2009;13:343–403. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallegos NC, Dawson J, Jarvis M, Hobsley M. Risk of strangulation in groin hernias. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1171–1173. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration Repair of groin hernia with synthetic mesh: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2002;235:322–332. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingsnorth A, LeBlanc K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet. 2003;362:1561–1571. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turrentine FE, Wang H, Simpson VB, Jones RS. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa G, ERASO (Elderly Risk Assessment for Surgical Outcome) Collaborative Study Group. Massa G. Frailty and emergency surgery in the elderly: protocol of a prospective, multicenter study in Italy for evaluating perioperative outcome (The FRAILESEL Study) Updates Surg. 2018;70:97–104. doi: 10.1007/s13304-018-0511-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245–2125. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rashid M, Kwok CS, Gale CP, et al. Impact of co-morbid burden on mortality in patients with coronary heart disease, heart failure, and cerebrovascular accident: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2017;3:20–36. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan J, Wang Y-X, Li Z-P. Predictive value of the POSSUM, p-POSSUM, cr-POSSUM, APACHE II and ACPGBI scoring systems in colorectal cancer resection. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:1464–1473. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Echara ML, Singh A, Sharma G. Risk-adjusted analysis of patients undergoing emergency laparotomy using POSSUM and P-POSSUM Score: a prospective study. Niger J Surg. 2019;25:45–51. doi: 10.4103/njs.NJS_11_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borchardt RA, Tzizik D. Update on surgical site infections: the new CDC guidelines. JAAPA. 2018;31:52–54. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000531052.82007.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgibbons RJ, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gibbs JO, et al. Watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men. JAMA. 2006;295:285. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Dwyer PJ, Chung L. Watchful waiting was as safe as surgical repair for minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Evid Based Med. 2006;11:73. doi: 10.1136/ebm.11.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birindelli A, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, et al. 2017 update of the WSES guidelines for emergency repair of complicated abdominal wall hernias. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:37. doi: 10.1186/s13017-017-0149-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehlet H, Bay-Nielsen M, Collaboration DHD. Nationwide quality improvement of groin hernia repair from the Danish Hernia Database of 87,840 patients from 1998 to 2005. Hernia. 2008;12:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helgstrand F, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H, Bisgaard T. Outcomes after emergency versus elective ventral hernia repair: a prospective nationwide study. World J Surg. 2013;37:2273–2279. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pokorny H, Klingler A, Schmid T, et al. Recurrence and complications after laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair: results of a prospective randomized multicenter trial. Hernia. 2008;12:385–389. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilsson H, Nilsson E, Angerås U, Nordin P. Mortality after groin hernia surgery: delay of treatment and cause of death. Hernia. 2011;15:301–307. doi: 10.1007/s10029-011-0782-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez Pérez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, et al. Emergency hernia repairs in elderly patients. Int Surg. 2003;88:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahlstrand U, Wollert S, Nordin P, et al. Emergency femoral hernia repair: a study based on a national register. Ann Surg. 2009;249:672–676. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819ed943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bittner R, Sauerland S, Schmedt C-G. Comparison of endoscopic techniques vs Shouldice and other open nonmesh techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:605–615. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-9049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malik HA, Ghanshan, Mumtaz A, Bano F (2017) Postoperative pain in laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal versus Lichtenstein open mesh repair techniques for inguinal hernia. J Surg Pak 22(3):79–82. https://doi.org/10.21699/jsp.22.3.3

- 25.Zafar H, Zaidi M, Qadir I, Memon AA. Emergency incisional hernia repair: a difficult problem waiting for a solution. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2012;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xourafas D, Lipsitz SR, Negro P, et al. Impact of mesh use on morbidity following ventral hernia repair with a simultaneous bowel resection. Arch Surg. 2010;145:739–744. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request to the corresponding author.