Abstract

Objective:

Personalized normative feedback (PNF) interventions are effective at reducing hazardous drinking in college. However, little is known about who is most receptive to PNF. College women with a history of alcohol-related incapacitated rape (IR) are at elevated risk for hazardous drinking, but it is unclear what impact intervention messaging may have on this group and how their outcomes compare to those without past IR. To address this gap, this study involved secondary data analysis of a large web-based clinical trial.

Methods:

Heavy drinking college women (N=1,188) were randomized into PNF (n=895) or control conditions (n=293). Post-intervention, women reported their reactions to intervention messaging. Hazardous drinking outcomes (typical drinking, heavy episodic drinking, peak estimated blood alcohol content, blackout frequency) were assessed at baseline and 12 months.

Results:

Past IR was reported by 16.3% (n=194) of women. Women with history of IR reported more baseline hazardous drinking and greater readiness to change than women without IR. For those who received PNF, history of IR related to greater perceived impact of the intervention, but no difference in satisfaction with the message. After controlling for baseline drinking, regressions revealed the effect of PNF was moderated by IR for frequency of heavy episodic drinking at 12 months. Simple main effects revealed PNF was associated with lower levels of hazardous drinking at follow-up among women with past IR.

Conclusions:

This initial investigation suggests PNF is a low-resource and easily disseminated intervention that can have a positive impact on college women with past IR.

Keywords: alcohol intervention, alcohol-involved sexual assault, drug-facilitated rape, web-based intervention, stages of change

Incapacitated rape (IR)—nonconsensual sex when an individual is unable to consent or resist due to intoxication—is a pervasive problem on college campuses (Carey et al., 2015; Mohler-Kuo et al., 2004). Alcohol is central to the settings where college women socialize (e.g., parties, bars; Borsari & Carey, 2001), and is the primary substance in the vast majority of IR (Kilpatrick et al., 2007). Drinking alcohol—heavy episodic drinking in particular (HED; 4+ drinks for women; NIAAA, 2004)—is not only a risk factor for IR (McCauley et al., 2010), but can also be a consequence. Compared to women without IR or another type of sexual assault, women with a history of IR engage in more HED (Lawyer et al., 2010; McCauley et al., 2010; Norris et al., 2019), use fewer alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies (Gilmore, Stappenbeck, et al., 2015), and experience more alcohol-related consequences (Kaysen et al., 2006), including blackouts (Voloshyna et al., 2018). Consistent with the self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian, 1997), hazardous drinking may reflect efforts to cope with IR-related distress. However, hazardous drinking can also prolong post-assault distress (Kaysen et al., 2011; Read et al., 2013) and increase risk for subsequent IR (Griffin & Read, 2012; Messman-Moore et al., 2013; Testa et al., 2010; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2015). Thus, intervention efforts to reduce hazardous drinking in this at-risk group should be a high priority.

One prominent approach to alcohol intervention is based in social norms theory, which holds that behaviors like hazardous drinking are shaped by perceptions of peers’ attitudes toward, and involvement with, that behavior (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). Indeed, perceived social norms are one of the most robust predictors of college student alcohol use (Neighbors et al., 2007). Findings consistently show that college students overestimate their peers’ drinking, which increases risk for their own hazardous drinking (Cox et al., 2019; Lewis & Neighbors, 2004). Many harm-reduction strategies leverage these powerful peer influences by correcting normative misperceptions.

One of the most widely used norm-correction strategies is personalized normative feedback (PNF; Dotson et al., 2015). PNF is designed to correct normative misperceptions by providing individuals with feedback that contrasts (a) their own alcohol use, (b) their perceptions of how much peers drink, and (c) how much peers actually drink. Discrepancies between perceived and actual peer drinking are highlighted through text and graphics alongside individuals’ own alcohol use for a personalized comparison. Relative to control conditions, PNF interventions have considerable short-term efficacy (Cronce & Larimer, 2012; Neighbors et al., 2016), and may be particularly effective in women (Saitz et al., 2007). Despite promising short-term effects, web-based alcohol interventions including PNF have been less likely to demonstrate long-term efficacy (e.g., at 12 months; Dedert et al., 2015; Donoghue et al., 2014; Riper et al., 2014) and less is known about which students might be most receptive to these interventions.

As with any harm-reduction strategy, PNF interventions are effective to the extent to which students resonate with the goal of reducing hazardous drinking. For example, there is initial evidence that students who report more readiness to change also respond more effectively to PNF and other web-based substance use interventions (Lee et al., 2010; Palfai et al., 2016; Young, 2016; for exception, see Collins et al., 2010). In one study, students with more alcohol-related consequences were more receptive to PNF, showing reduced weekly drinking and HED at 1-month post-intervention (Palfai et al., 2011). Given that IR can also be conceptualized as a serious consequence of alcohol use, students with past IR may be particularly motivated to reduce their hazardous drinking, and thus, more responsive to PNF.

More than just a negative consequence of drinking, IR is also a traumatic event that can trigger negative cognitions. Similar to other traumas, IR can “shatter” positive assumptions and contribute to negative beliefs about the world, others, and oneself (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Vogt et al., 2012). Negative cognitions regarding self-blame can be particularly prominent following alcohol-involved sexual assaults including IR, even relative to other forms of sexual assault (Donde, 2017; Littleton et al., 2009; Peter-Hagene & Ullman, 2015, 2018). The perpetrator holds the sole responsibility for IR, yet to obtain a sense of control, survivors may be motivated to view drinking as a controllable behavior that, if avoided, could prevent past or future victimization, contributing to behavioral self-blame. Survivors who tell peers about the IR can also be met with negative social reactions (Relyea & Ullman, 2015; Ullman & Najdowski, 2010), as informal supports may convey blame for drinking (e.g., “That’s what happens when girls drink”; Ullman, 2010, p. 67). These negative cognitions may complicate the delivery of alcohol-focused interventions for individuals who have experienced IR. Content standard in PNF, such as highlighting that an individual’s alcohol use is higher than their peers, could activate negative cognitions about drinking and unhelpful beliefs about blame. From this perspective, PNF might create discomfort for those with a history of IR. It is unclear what implications this might have for effectiveness of the PNF intervention on alcohol-related outcomes.

Whereas complex cognitions regarding post-IR drinking could be carefully navigated by a therapist, web-based interventions, such as PNF, include standardized content that has not yet been widely tested in relation to IR. A small, yet growing literature suggests women with a sexual assault history—including both IR and other forcible or coerced unwanted sexual experiences—report some degree of discomfort in response to web-based alcohol intervention content (Jaffe et al., 2018) and may inaccurately fear that drinking connotes blame for the assault (Gulati et al., 2021). Only one known study (Gilmore, Lewis, et al., 2015) has evaluated the efficacy of a web-based alcohol intervention by sexual assault history. This intervention also included content on sexual assault risk reduction. Treatment efficacy was moderated by sexual assault severity, such that treatment effects for the combined intervention on reducing HED frequency was stronger at higher levels of assault severity. Although these findings did not distinguish between IR and other sexual assaults not involving alcohol, IR represents nearly three-quarters of sexual assaults in college women (Mohler-Kuo et al., 2004). Whether differences in response to web-based alcohol interventions are specific to IR given the unique implications for alcohol-related cognitions remains unknown.

The Current Study

In sum, although prior research supports the efficacy of PNF interventions relative to control in reducing alcohol use, it is unknown if this treatment effect differs by history of IR. The response to alcohol interventions among women with a history of IR is particularly important given that these women are at elevated risk for hazardous drinking, and may also react negatively to alcohol intervention messaging. To better understand whether reactions to and efficacy of PNF differs for survivors of IR, the current study involved secondary analysis of two large randomized clinical trials of PNF targeting alcohol consumption in college students (LaBrie et al., 2013; Larimer et al., 2021). We focus here on women as the gender disproportionately affected by rape (reported by 21.3% of women and 2.6% of men in the US; Smith et al., 2018) and hazardous drinking as particularly relevant and problematic after IR (e.g., increasing risk for subsequent IR; Testa et al., 2010; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2015).

Our first aim was to characterize baseline differences between college women with and without a history of alcohol-related IR. Consistent with past research, we expected IR would be associated with more hazardous drinking and greater readiness to change. Our second aim was to characterize reactions to the intervention among women randomly assigned to PNF. We expected IR to be associated with lower satisfaction with the intervention message (given concerns about blame for past IR) and greater perceived impact of the message (given greater readiness to change). Our final aim was to explore differential treatment effects on hazardous drinking by history of IR. One possibility is that alcohol-related intervention content may feel personally relevant to women with past IR, leading to greater treatment-related changes in hazardous drinking. On the other hand, PNF may be insufficient to reduce drinking to cope with IR-related distress. Women with past IR may also react negatively and disengage from intervention content, and in turn show fewer treatment-related changes in hazardous drinking over time.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were drawn from two large randomized clinical trials (RCTs) assessing the efficacy of web-based PNF interventions on alcohol use (see LaBrie et al., 2013; Larimer et al., 2021). Both RCTs entailed identical recruitment procedures, and the same items were used to assess relevant constructs at similar follow-up intervals. Both RCTs were integrated in the current secondary data analysis in order to increase the number of participants with past IR (to avoid small cell sizes) and is justified given the intervention components of aggregated conditions and procedures were nearly identical across the two studies.

To facilitate generalizability, the larger trials recruited college students from two US sites: a large public Pacific Northwest university (Campus 1) and a mid-sized private West Coast university (Campus 2). Both RCTs recruited participants from the same two universities. The Institutional Review Boards of both universities approved all research procedures, and a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained to further protect research participants.

In the first RCT (i.e., RCT-1; LaBrie et al., 2013), 11,069 students were invited to complete baseline screening (4,818 responses; 43.5% response rate) and 2,034 (42.2%) met screening criteria of at least one past-month event of HED (i.e., 4+/5+ drinks per occasion for females/males, respectively) and identifying as either White or Asian to facilitate race-specific normative feedback. Of those, 1,831 (90.0%) completed the baseline survey and were randomized into one of 11 conditions. Random assignment was stratified by sex, race, Greek status, and total drinks per week (<11 drinks vs. ≥11 drinks). Eight conditions involved PNF with descriptive norms presented in reference to specific groups, including typical student as well as one to three specific reference groups via all possible combinations of gender, race, and/or Greek status. One condition involved more comprehensive, motivational feedback based on the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (Dimeff et al., 1999), referred to as Web-BASICS. Two control conditions not involving an active intervention were: (a) a generic feedback control with similar design and length as the PNF, but with content covering media usage instead of alcohol use, and (b) a minimal assessment condition with no PNF. All participants completed a post-intervention follow-up survey at 12-months. Those not in the minimal assessment condition also completed surveys at 1-, 3-, and 6-months (not reported on here). Participants were compensated $15 for screening, $25 for baseline, $30 for 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-ups, $40 for 12-month follow-up, and $30 as a bonus for completing all procedures. Results from the larger trial (LaBrie et al., 2013) revealed that PNF normed to a “typical student” was more effective than more specific reference groups. Still, considered in aggregate, PNF was more effective than the generic feedback control in reducing alcohol consumption, though effects were modest.

Following similar procedures, the second RCT (i.e., RCT-2; Larimer et al., 2021) invited 5,998 students to complete baseline screening (2,688 responses; 44.8% response rate). A total of 1,494 (55.6%) students met the RCT-2 screening criteria of at least one past-month event of HED (i.e., 4+/5+ drinks per occasion for females/males, respectively). Of those, 1,367 (91.5%) completed the baseline survey and were randomized into one of six conditions. Randomization in RCT-2 was stratified by total drinks per week (<11 drinks vs. ≥11 drinks). The three PNF conditions were (a) descriptive norms feedback (in reference to a typical student), (b) injunctive norms feedback, and (c) both descriptive and injunctive norms feedback. One condition entailed Web-BASICS, one was a generic feedback control condition with repeated assessments (identical to the control condition in RCT-1), and the final condition was a minimal assessment control. Participation incentives included $15 for the screening survey, $25 for the baseline survey, $25 for completing the three-month follow-up, $30 for the six-month follow-up, and $35 for completing the 12-month follow-up. The primary findings from RCT-2 indicated that PNF conditions (including the descriptive-norms-only condition) yielded favorable effects on weekly drinking and alcohol-related consequences compared to the repeated assessment control condition (Larimer et al., 2021).

Several factors were considered when selecting participants for the current study. First, given that sexual victimization is disproportionately higher in college women than men (Hines et al., 2012), analyses were limited to cisgender1 women (sample limited to n = 1,872). Second, analyses were designed with the small number of participants with IR per cell in mind. Each condition from the parent studies contained between 10–28 women with a history of IR. Because findings may be unstable from small cell sizes, only aggregated conditions (i.e., representing two or more trial conditions with a comparable intervention component) were considered. Specifically, a treatment group involving descriptive PNF was created by combining the eight descriptive norms PNF conditions from RCT-1 and the descriptive-norms-only PNF from RCT-2. The Web-BASICS conditions were excluded from the current analyses because it was a substantially longer intervention (Web-BASICS: 26 pages, PNF: 4 pages) and contained a greater range of content that might evoke unique reactions from women with past IR (e.g., feedback on alcohol and sexual behavior). A control comparison group was created by combining the two generic feedback control conditions from each larger trial along with the minimal assessment condition2 from RCT-1 (minimal assessment in RCT-2 did not assess IR at baseline). Because the minimal assessment control did not complete surveys at 1-, 3-, or 6-months, full data from the aggregate control condition were not available at these timepoints. Thus, current analyses focused only on the baseline and 12-month follow-up surveys. Third, because IR was a focus of the current study, 1 participant assigned to treatment was excluded for missing IR data.

The current study involved 1,188 college women. On average, participants were 19.86 years of age (SD = 1.31). With regard to racial background, 75.9% identified as White, 20.0% as Asian, 2.0% as multiracial, 0.9% as Black/African American, 0.3% as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 0.1% as American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 0.8% as another race. In addition, 30.7% were members of a Greek organization. Considering the aggregated trial conditions, 895 were randomly assigned to a PNF condition, whereas 293 were assigned to control. Across conditions, 16.3% (n = 194) reported a history of IR, including 16.0% (n = 143) of those assigned to PNF and 17.4% (n = 51) of those assigned to control reporting a past IR. Amongst the 194 women with a lifetime history of IR, about half (52.1%; n = 101) had experienced IR in the past year (1 time: 37.1%, n = 72; 2 times: 13.4%, n = 26; 3+ times: 1.5%, n = 3), and the other half (47.9%; n = 93) had experienced IR but not in the past year, with no difference between PNF and control, χ2(df = 1, N = 194) = 0.69, p = .405.

Measures

Demographics.

At screening, students reported their birth sex, gender identity, racial background, and Greek membership.

History of IR.

At baseline, participants were asked one item on the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut & Sher, 1992) regarding history of alcohol-related IR. Consistent with past work on IR (Kaysen et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2010), participants were asked, “Have you ever been pressured or forced to have sex with someone because you were too drunk to prevent it?” Responses were dichotomized, with history of IR indicated by a response of yes, but not in the past year or one, two, or three or more times in the past year (IR = 1) and no IR indicated by a response of no, never (IR = 0).

Readiness to change.

At baseline, participants completed the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (Rollnick et al., 1992). A total of 12 items were rated on a scale from −2 (strongly disagree) to 2 (strongly agree). Based on Prochaska and DiClemente’s (1986) model, the following three stages of change were assessed with four items each: pre-contemplation (i.e., not thinking about change), contemplation (i.e., thinking about change), and action (i.e., making changes). After reverse-coding pre-contemplation items, a total score was computed (−24 to +24), with higher scores reflecting greater readiness to reduce one’s drinking (α = .87). To further characterize baseline differences, each participant’s stage of change was also determined, as indicated by the highest rated subscale, or when subscales were equal, the furthest stage of change (Heather & Rollnick, 1993).

Reactions to PNF.

Participants assigned to PNF were asked to provide feedback on their reactions immediately after the intervention. Questions were designed specifically for this study. Perceived impact of the message was assessed with four items (α = .87), including whether the personalized information “increased my confidence to avoid drinking,” “had a positive impact on me,” “will cause me to reduce the amount I drink,” and “has positively affected my decision to avoid drinking situations.” Satisfaction with the message was assessed with two items (α = .85): “I liked the personalized information” and “I liked the message presented in the personalized information.” Response options ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) and mean scores were computed.

Hazardous drinking.

All drinking outcomes were assessed at screening or baseline (collectively referred to as “baseline”) and again at the 12-month follow-up. For all alcohol consumption measures, a definition of “standard drink” was provided.

AUDIT-C.

The three-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption scale (AUDIT-C; Bush et al., 1998) was used to assess hazardous drinking. Participants were asked how often they have a drink containing alcohol, the number of drinks on a typical drinking day, and the frequency of having six or more drinks on one occasion. Response options were specific to each question type and ranged from 0 (never / 1–2 drinks) to 4 (4+ times a week / 10+ drinks). Responses were summed to create a total score (0 to 12). Prior work has supported the internal reliability and concurrent validity of the AUDIT-C in college students (Barry et al., 2015), and with a cut-score of 5 recommended to detect hazardous drinking in college women (DeMartini & Carey, 2012). In the current study, alpha coefficients were .67 and .68 for baseline and 12 months, respectively.

Peak estimated blood alcohol content (eBAC).

Participants were asked (a) the maximum number of drinks consumed on a single occasion within the past 30 days and (b) the number of hours spent drinking on that occasion (Dimeff et al., 1999). Following recommendations from Matthews and Miller (1979), peak eBAC was calculated as: [(number of drinks/2) × (gender constant/ body weight)] — (.016 × hours). Consistent with past research handling extreme values of peak eBAC (e.g., Martens et al., 2010), outliers were capped at 0.40.

HED frequency.

Participants completed the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985) to report the number of drinks typically consumed each day of the week in the past month. The number of days on a typical week in which participants reported HED (i.e., 4+ drinks for women) was computed (possible range = 0 to 7).

Blackout frequency.

One item on the YAAPST (Hurlbut & Sher, 1992) assessed past-year blackout frequency. Specifically, participants were asked, “Have you awakened the morning after a good bit of drinking and found that you could not remember a part of the evening before?” Responses were coded as 0 = no past-year blackouts (indicated by response options: No, never or Yes, but not in the past year), 1 = One time in the past year, 2 = Two times in the past year, and 3 = Three or more times in the past year.

Data Analysis

Preliminary analyses involved examining descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables. To address the first aim, t-tests and chi-square tests were conducted to evaluate baseline differences by IR. Regarding the second aim, in the subset of participants who completed PNF, reactions to PNF by IR were assessed with t-tests. Finally, for the third aim, hazardous drinking outcomes were evaluated using intent-to-treat analyses in Mplus version 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Separate regression models were estimated to predict each outcome at 12-months, controlling for the baseline value of the variable.3 Hierarchical models were conducted to evaluate main effects of IR and PNF (Step 1) and then interactive effects of IR and PNF (Step 2). Given that readiness to change was associated with both IR and drinking outcomes in bivariate associations, readiness to change was also explored as a possible covariate in Step 3. Simple main effects were calculated for the most conservative model (Step 3). All outcomes were considered continuous4 and modeled with maximum likelihood estimation and standard errors robust to non-normality (MLR), which assumes data are missing at random (MAR). Data at the 12-month assessment were available for 87.1% (n = 1,035) of participants. Missingness was evaluated for associations with demographic and alcohol use variables at baseline; only older age was associated with missing follow-ups (p = .016). Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted, retaining all participants in each model, regardless of missing data. Specifically, covariances between exogenous variables were estimated to bring all variables into the likelihood and therefore, retain all participants with any data at baseline.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the overall sample are presented in Table 1. Generally, drinking outcomes were interrelated within and across timepoints. Readiness to change was associated with more hazardous drinking at baseline and follow-up. Perceived impact and satisfaction with the PNF message were positively correlated. Readiness to change was associated with a greater perceived impact of the message, but not with satisfaction. Satisfaction with the PNF message was associated with lower AUDIT-C scores at follow-up; reactions to PNF were not associated with any other drinking outcomes.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| Variable | Observed Range | M | SD | Correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||

| 1. Readiness to change | −24 to 23 | −3.39 | 8.34 | ||||||||||

| 2. PNF: perceived impact | 0 to 6 | 2.94 | 1.22 | .34** | |||||||||

| 3. PNF: satisfaction of message | 0 to 6 | 4.30 | 1.20 | .00 | .28** | ||||||||

| 4. AUDIT-C: Baseline | 1 to 11 | 5.07 | 1.95 | .26** | −.06 | −.05 | |||||||

| 5. AUDIT-C: 12-months | 1 to 11 | 4.78 | 1.96 | .15** | −.03 | −.08* | .57** | ||||||

| 6. Peak eBAC: Baseline | .00 to .40 | 0.17 | 0.09 | .18** | .06 | −.03 | .56** | .30** | |||||

| 7. Peak eBAC: 12-months | .00 to .40 | 0.14 | 0.09 | .13** | −.03 | −.05 | .43** | .67** | .44** | ||||

| 8. HED frequency: Baseline | 0 to 6 | 1.13 | 1.17 | .23** | .05 | −.08* | .72** | .46** | .51** | .35** | |||

| 9. HED frequency: 12-months | 0 to 7 | 0.96 | 1.17 | .14** | .02 | −.07 | .48** | .71** | .31** | .57** | .46** | ||

| 10. Blackout frequency: Baseline | 0 to 3 | 1.44 | 1.23 | .34** | −.01 | −.01 | .50** | .37** | .33** | .32** | .42** | .29** | |

| 11. Blackout frequency: 12-months | 0 to 3 | 1.23 | 1.24 | .20** | −.02 | .00 | .40** | .53** | .25** | .43** | .33** | .40** | .53** |

Note. M = mean, SD = standard deviation, PNF = personalized normative feedback, AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Consumption scale, eBAC = estimated Blood Alcohol Concentration, HED = heavy episodic drinking,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Baseline Differences

Group differences by history of IR are shown in Table 2. Women with an IR history were slightly younger, but there were no other demographic differences between college women with and without past IR. At baseline, all indicators of hazardous drinking were higher in women with (vs. without) IR. For example, the proportion of women who met criteria for hazardous drinking based on the AUDIT-C cut-score was 66.8% for women with IR compared to 53.0% without IR. Women with past IR also reported more readiness to change at baseline (41.2% in the action phase) compared to their peers without IR (29.3% in the action phase).

Table 2.

Group Differences

| Variable | No IR (n = 994) | History of IR (n = 194) | Test of Difference | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| RCT-1 (vs. RCT-2) | 76.0% (755) | 74.7% (145) | χ2(1) = 0.13, p = .718 | ϕ = −0.01 |

| Public campus (vs. private) | 58.9% (585) | 57.2% (111) | χ2(1) = 0.18, p = .672 | ϕ = −0.01 |

| Age at baseline | 19.91 (1.32) | 19.63 (1.22) | t(1186) = 2.64, p = .008** | d = −0.21 |

| Asian | 20.7% (204) | 16.8% (32) | χ2(1) = 1.53, p = .216 | ϕ = −0.04 |

| Greek member | 30.0% (297) | 34.5% (67) | χ2(1) = 1.56, p = .211 | ϕ = 0.04 |

| Baseline | ||||

| AUDIT-C score | 4.98 (1.95) | 5.52 (1.87) | t(1183) = −3.53, p < .001*** | d = 0.28 |

| AUDIT-C ≥ 5 | 53.0% (526) | 66.8% (129) | χ2(1) = 12.473, p < .001*** | ϕ = 0.10 |

| Peak eBAC | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.20 (0.09) | t(1186) = −3.88, p = .001** | d = 0.30 |

| HED frequency | 1.08 (1.14) | 1.39 (1.29) | t(1183) = −3.35, p < .001*** | d = 0.26 |

| Blackout frequency | 1.34 (1.23) | 1.95 (1.14) | t(1185) = −6.42, p < .001*** | d = 0.50 |

| Readiness to change score | −4.02 (8.16) | −0.14 (8.50) | t(1186) = −6.01, p < .001*** | d = 0.47 |

| Stage of change | χ2(2) = 22.37, p < .001*** | V = 0.14 | ||

| Pre-contemplation | 56.6% (563) | 38.1% (74) | ||

| Contemplation | 14.1% (140) | 20.6% (40) | ||

| Action | 29.3% (291) | 41.2% (80) | ||

| Treatment | ||||

| Randomly assigned to PNF | 75.7% (752) | 73.7% (143) | χ2(1) = 0.33, p = .566 | ϕ = −0.02 |

| PNF: perceived impact | 2.89 (1.19) | 3.16 (1.34) | t(792) = −2.23, p = .026* | d = 0.22 |

| PNF: satisfaction with message | 4.31 (1.19) | 4.29 (1.25) | t(791) = 0.18, p = .860 | d = −0.02 |

| Completed 12-month follow-up | 88.0% (875) | 88.1% (171) | χ2(1) = 0.00, p = .964 | ϕ = 0.00 |

Note. Means (standard deviations) or percentages (n) are reported. Effect sizes should be interpreted with reference to the statistic reported; small, medium, and large effects are reflected by phi (ϕ) of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5, Cramer’s V (for the 2×3 comparison) of 0.07, 0.21, and 0.35, and Cohen’s d of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively. Cell sizes vary slightly due to missing data (up to n = 2 missing for demographic and baseline values). IR = incapacitated rape, AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Consumption scale, eBAC = estimated Blood Alcohol Concentration, HED = heavy episodic drinking, PNF = personalized normative feedback,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Reactions to Treatment

Among the 895 participants randomly assigned to PNF, 88.9% completed at least one of the measures on reactions to PNF, though there was no difference in completion of these questions by IR history (p = .412). Among those in PNF, women with a history of IR perceived greater impact of PNF on their drinking than women without a history of IR. However, there was no difference in satisfaction with PNF content based on women’s history of IR (Table 2).

Treatment Efficacy

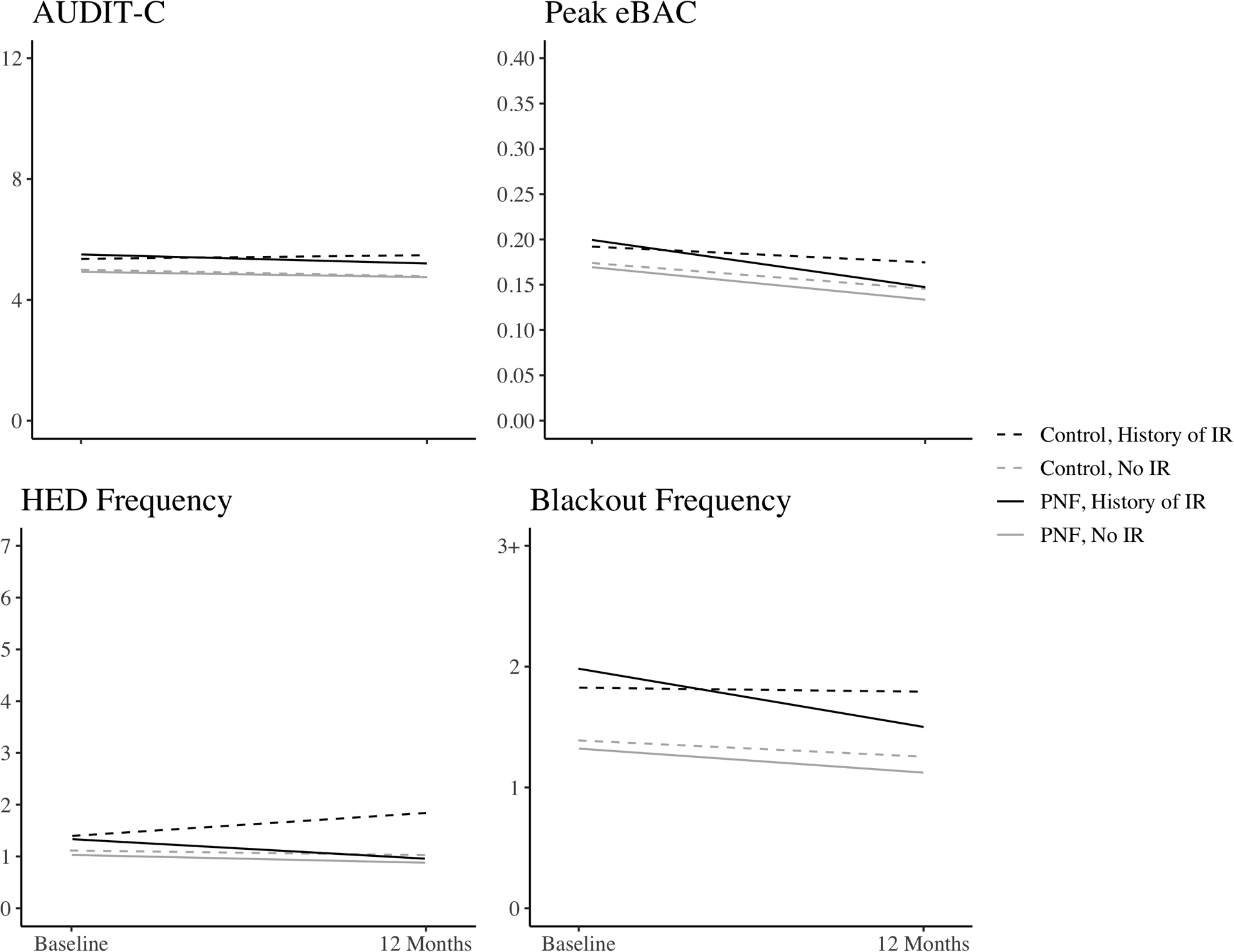

Group means by IR history, condition, and time are represented in Figure 1. Regression results are presented in Table 3. The overall variance accounted for by the full models ranged from 19.3% for peak eBAC to 33.1% for AUDIT-C. At Step 1, there were no significant main effects of IR after controlling for baseline values on any 12-month measure of hazardous drinking, but there were significant main effects for PNF reducing peak eBAC and HED frequency. At Step 2, there was a significant interaction between IR and PNF for HED frequency, which remained significant at Step 3 when controlling for readiness to change – a non-significant predictor of all outcomes. To probe the interactions at Step 3, simple main effects were computed (see Table 4). PNF was associated with significantly less frequent HED among women with past IR, but not women without IR. Additionally, among those in the control condition, women with (vs. without) IR reported more frequent HED, whereas there was no such difference by IR history for women assigned to PNF. There were no significant interactions between IR and PNF for the other hazardous drinking outcomes.

Figure 1.

Mean drinking outcomes represented by condition and history of incapacitated rape at baseline and the 12-month follow-up. PNF = personalized normative feedback; IR = incapacitated rape, AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Consumption scale, eBAC = estimated Blood Alcohol Concentration, HED = heavy episodic drinking.

Table 3.

Regression Results for Drinking Outcomes at the 12-month Follow-up (N = 1188)

| Step1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE | p | R 2 | B | SE | p | R 2 | B | SE | p | R 2 |

| AUDIT-C | 32.8% | 33.0% | 33.1% | |||||||||

| Baseline covariate | 0.57 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.57 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.57 | 0.03 | <.001 | |||

| IR | 0.25 | 0.15 | .085 | 0.64 | 0.28 | .022 | 0.63 | 0.28 | .026 | |||

| PNF | −0.07 | 0.12 | .530 | 0.02 | 0.13 | .896 | 0.02 | 0.13 | .883 | |||

| IR × PNF | −0.53 | 0.33 | .107 | −0.53 | 0.33 | .107 | ||||||

| Readiness to change | 0.00 | 0.01 | .645 | |||||||||

| Peak eBAC | 19.3% | 19.4% | 19.6% | |||||||||

| Baseline covariate | 0.44 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.44 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.44 | 0.03 | <.001 | |||

| IR | 0.01 | 0.01 | .450 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .223 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .282 | |||

| PNF | −0.01 | 0.01 | .025 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .098 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .108 | |||

| IR × PNF | −0.02 | 0.02 | .336 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .337 | ||||||

| Readiness to change | 0.00 | 0.00 | .106 | |||||||||

| HED Frequency | 22.4% | 23.8% | 23.9% | |||||||||

| Baseline covariate | 0.46 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.46 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.45 | 0.03 | <.001 | |||

| IR | 0.12 | 0.10 | .242 | 0.75 | 0.26 | .004 | 0.73 | 0.26 | .005 | |||

| PNF | −0.22 | 0.08 | .007 | −0.08 | 0.08 | .323 | −0.08 | 0.08 | .341 | |||

| IR × PNF | −0.84 | 0.28 | .002 | −0.84 | 0.28 | .002 | ||||||

| Readiness to change | 0.01 | 0.00 | .206 | |||||||||

| Blackout Frequency | 28.5% | 28.5% | 28.5% | |||||||||

| Baseline covariate | 0.53 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.53 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.52 | 0.03 | <.001 | |||

| IR | 0.09 | 0.10 | .358 | 0.21 | 0.19 | .252 | 0.21 | 0.19 | .265 | |||

| PNF | −0.12 | 0.08 | .115 | −0.09 | 0.08 | .265 | −0.09 | 0.08 | .269 | |||

| IR × PNF | −0.17 | 0.22 | .434 | −0.17 | 0.22 | .434 | ||||||

| Readiness to change | 0.00 | 0.00 | .692 | |||||||||

Note. Bolded values are statistically significant at p < .05. Bolded, italicized terms represent drinking outcomes. Baseline covariate refers to the baseline assessment of the corresponding drinking outcome. AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Consumption scale, eBAC = estimated Blood Alcohol Concentration, HED = heavy episodic drinking, IR = incapacitated rape, PNF = personalized normative feedback.

Table 4.

Simple Main Effects from Step 3 Regression Models

| Simple Main Effect | AUDIT-C | Peak eBAC | HED frequency | Blackout frequency | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| PNF vs. control: no IR | 0.02 | 0.13 | .883 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .108 | −0.08 | 0.08 | .341 | −0.09 | 0.08 | .269 |

| PNF vs. control: IR | −0.51 | 0.30 | .093 | −0.03 | 0.02 | .079 | −0.92 | 0.26 | <.001 | −0.26 | 0.20 | .190 |

| IR vs. no IR: control | 0.63 | 0.28 | .026 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .282 | 0.73 | 0.26 | .005 | 0.21 | 0.19 | .265 |

| IR vs. no IR: PNF | 0.10 | 0.17 | .544 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .959 | −0.11 | 0.10 | .270 | 0.04 | 0.11 | .714 |

Note. Bolded values are statistically significant at p < .05. AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Consumption scale, eBAC = estimated Blood Alcohol Concentration, HED = heavy episodic drinking, IR = incapacitated rape, PNF = personalized normative feedback.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of two PNF trials represents the first known investigation of reactions to and outcomes of a web-based alcohol intervention by IR history. Both in past research and the current study, IR was associated with hazardous drinking, suggesting college women with past IR are an at-risk population meriting intervention. Although web-based interventions have the potential to be widely disseminated to heavy-drinking women, we expected that IR may lead to complex or competing cognitions regarding alcohol use that may be difficult to navigate in standardized web-based content. However, findings suggested women with IR perceived PNF to be more impactful than women without IR and were similarly satisfied with the PNF message. Further, PNF was particularly effective in college women with a history of IR in that it was associated with lower heavy episodic drinking in the year following the intervention.

The first aim of this study was to characterize baseline differences between college women with and without IR prior to the intervention. Within this large sample of heavy-drinking college women, 16.3% reported a lifetime history of IR. This rate is higher than previous studies of college women generally (e.g., Kilpatrick et al., 2007) and likely reflects higher prevalence of sexual victimization in heavier drinking populations (Testa & Livingston, 2018). At baseline, women with past IR also reported more hazardous drinking relative to women without IR. These findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating IR is associated with subsequent elevations in hazardous drinking (Kaysen et al., 2006) including HED (Lawyer et al., 2010; McCauley et al., 2010) and blackout frequency (Voloshyna et al., 2018), but extends this work to reveal elevations in past-month peak eBAC. Of note, these baseline differences are cross-sectional and it is therefore unclear whether hazardous drinking patterns were established before the IR or escalated after the IR, though past prospective research (Kaysen et al., 2006) suggests both processes may contribute to drinking patterns in the current sample. Consistent with past work showing greater readiness to change among heavier drinkers with more alcohol-related consequences (Vik et al., 2000), women with past IR reported greater readiness to change than women without IR. Taken together, findings suggest IR is associated with hazardous drinking, perhaps to cope with IR-related distress. At the same time, IR survivors may be acutely aware that heavy drinking confers risk, and many indicated they were considering or actively trying to reduce their drinking. Alcohol use and drinking settings may also be a reminder of past IR (Jaffe et al., 2019), and related distress may also motivate IR survivors to reduce their drinking.

Second, we considered responses to PNF. Primed for change, women with past IR were particularly likely to perceive the current study’s PNF message as impactful. Contrary to expectations, IR history was not associated with differences in satisfaction with the PNF message. This suggests alcohol-related PNF may not activate blame-related cognitions about drinking after IR, at least not in a way that interferes with receiving the PNF message. More research is needed to specifically examine perceptions of blame and other cognitions that may contribute to satisfaction with the message. These findings are consistent with a prior study that found no differences by sexual assault history in comfort with an alcohol-focused web-based intervention (Jaffe et al., 2018). Although satisfaction with PNF was not compared to any other conditions in the current study, Jaffe et al. (2018) also found that among college women with a sexual assault history, comfort was lower in the alcohol-only intervention relative to a sexual assault risk reduction intervention and minimal assessment. Considering these findings in aggregate, it is important to note the current PNF intervention only involved corrective drinking norms, whereas the prior intervention also included instruction on protective behavioral strategies, which a recent qualitative study suggests may be perceived by sexual assault survivors as evoking blame for drinking (Gulati et al., 2021). Thus, the current findings reveal that minimalist web-based information regarding drinking norms may be particularly impactful and similarly satisfactory after IR, but more research is needed to understand how women with past IR might react to specific strategies to prevent future alcohol-related harms. Additional research is also needed to understand if and how such subjective reactions may relate to intervention outcomes. In the current study, subjective reactions to PNF were not associated with hazardous drinking at baseline or follow-up, suggesting participants’ perceptions of PNF efficacy at the time of the intervention do not map onto observed outcomes in the long-term.

Finally, we evaluated PNF efficacy by IR on hazardous drinking 12 months after the intervention. Initial models revealed that after controlling for baseline levels of drinking outcomes and IR history, there were significant effects of PNF on hazardous drinking outcomes of peak eBAC and HED frequency. The fact that PNF did not have significant effects on the AUDIT-C or blackout frequency is consistent with past research suggesting PNF is most effective at reducing hazardous drinking in the short-term, with less robust effects over time (Dedert et al., 2015; Donoghue et al., 2014; Riper et al., 2014).

Current findings also revealed that long-term PNF efficacy for reducing HED frequency was moderated by history of IR. For women without a history of IR, there were no significant differences between PNF and control on HED frequency at 12 months. This suggests the long-term effects of PNF—which were modest in the original RCT-1 trial—were too small to detect in this specific group. Consistent with past findings that web-based alcohol interventions are more effective for those with greater baseline alcohol consequences (Palfai et al., 2011) and more severe sexual assault histories (Gilmore, Lewis, et al., 2015), PNF was significantly associated with lower HED frequency only among college women with past IR.

Of note, IR only moderated PNF efficacy for one of four hazardous drinking outcomes examined in this study. It is possible that PNF in the presence of an IR history may specifically motivate changes in the occurrence of HED. That is, although PNF may lead to long-term reductions in consuming four or more drinks amongst women with past IR, when these women do choose to engage in heavy drinking episodes, PNF may not substantially reduce the total number of drinks (above four), the rate of drinking, or other protective behaviors that contribute to the AUDIT-C score, eBAC, or blackouts. However, non-significant trends for PNF were observed amongst women with past IR for reducing both AUDIT-C and eBAC, suggesting some consistency in the direction of effects across hazardous drinking outcomes.

Taken together, PNF was associated with less post-IR hazardous drinking, perhaps because alcohol-related intervention content felt personally relevant to these women who then reduced their drinking. Although we focused on IR in this study, PNF may also be particularly effective in the long-term for other trauma-exposed groups who are at risk for escalating alcohol use, or individuals with a personal history of serious alcohol consequences that motivates them to be receptive to intervention content. Although we expected IR-related readiness to change would contribute to these effects, readiness to change at baseline did not improve the prediction of hazardous drinking outcomes. This suggests factors beyond IR-related motivation to change (e.g., coping drinking motives, shifting social networks after IR) will be important to evaluate in future intervention research.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the current study include a large sample and consideration of long-term PNF outcomes related to IR history. IR was assessed specifically with regard to pre-assault alcohol use, which may be more applicable to understanding reactions to alcohol interventions than sexual assault generally or IR involving drugs other than alcohol. Despite these strengths, findings should be interpreted in light of study limitations. First, the original trials did not include a comprehensive assessment of sexual assault or trauma history. Thus, associations between treatment outcomes and assault severity or type could not be examined, and women who did not endorse alcohol-related IR in the current study may have experienced other forms of sexual victimization not captured by the single IR item (e.g., unwanted sexual touching, attempted rape, IR involving substances other than alcohol). Given that Gilmore, Lewis, and George (2015) found that sexual assault severity moderated the efficacy of a combined alcohol and sexual assault risk reduction intervention, we encourage more comprehensive assessments of sexual assault in future alcohol intervention research to better understand whether severity, frequency, or recency of IR might affect responses to alcohol-specific interventions. In addition, IR may be associated with other predictors of PNF response that were not examined here but have been established in prior research, such as posttraumatic stress (Monahan et al., 2013), depression (Miller et al., 2020), and drinking to cope (Young et al., 2016). Future research should disentangle the occurrence of IR from its sequelae when examining response to alcohol interventions.

Second, we aggregated general feedback control conditions with a minimal assessment control to evaluate a meaningfully sized subgroup of women with IR. This meant drinking outcomes could only be evaluated at timepoints completed by minimal assessment (baseline and 12-months) and more nuanced post-intervention trajectories of hazardous drinking could not be examined. Relatedly, we also aggregated across PNF conditions from the original RCT-1 trial, which evaluated norms presented for different reference groups and supplemented this with a PNF condition from a comparable RCT-2 trial. Although subgroup analyses were not possible within each of the PNF conditions, the variability in intervention effects may have added noise, making it more challenging to detect main and interactive effects of PNF. In addition, the original RCT-1 trial (LaBrie et al., 2013) revealed that one condition with PNF normed to a “typical student” was more effective to reduce drinking than the seven other conditions with PNF normed to more specific reference groups. Because most participants received these less effective versions of PNF, overall PNF efficacy may have been underestimated relative to more standard PNF administrations.

Finally, HED frequency was assessed for a typical week, which may underestimate HED over a set time period (e.g., past month). Although only heavy-drinking college students were included in the original trial, typical HED frequency was relatively low in this sample and thus, findings may be specific to students in this particular non-treatment seeking sample. Additionally, findings may not be generalizable to men, non-college students, or unrepresented ethnoracial groups. Rates of IR may differ between ethnoracial groups, and mechanisms underlying post-assault drinking may be affected by cultural differences and differ by identity (Littleton et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2010). We encourage efforts to replicate and extend the current findings, particularly in racial and gender minorities and men who have experienced IR.

Conclusions

Results of the present study provide initial support for the use of a brief web-based PNF intervention to reduce hazardous drinking among college women with past IR involving alcohol. Notably, women were similarly satisfied with the intervention message regardless of IR history, suggesting PNF content may not elicit self-blame cognitions as indicated in previous web-based alcohol interventions. Thus, women with past IR may be able to connect with the PNF material presented and enact behavioral changes regardless of their initial readiness to change. This initial investigation suggests web-based PNF, a low-resource intervention that can be easily and widely disseminated, has promise to reduce hazardous drinking in college women with a history of alcohol-related IR. Research replicating and extending this finding is suggested to further understand efficacy of web-based alcohol interventions after IR.

Public Health Significance Statement:

A web-based personalized normative feedback intervention for alcohol use was compared to a control condition in college women. This preliminary study revealed the intervention was particularly effective for women with a history of incapacitated rape in leading to less frequent heavy episodic drinking one year later.

Data Transparency Statement.

Data for this study were collected as part of two larger randomized clinical trials. Treatment outcomes of RCT-1 have only been reported in one prior publication (LaBrie et al., 2013). That publication focused on alcohol consumption in men and women assigned to PNF, Web-BASICS, or control conditions (excluding minimal assessment control), whereas the current study focused on hazardous drinking in women assigned to any PNF or control. LaBrie et al. (2013) did not report participants’ history of IR. Although several additional published manuscripts reported aspects of the data collected within the larger trial, none involved analysis of treatment outcomes or consideration of IR. Treatment outcomes of RCT-2 have only been reported in one prior manuscript (Larimer et al., 2021), which did not report participants’ history of IR.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; data collection was funded by R01AA012547 (PI: Larimer); manuscript preparation was supported by R37AA012547 (PI: Larimer), T32AA007455 (PI: Larimer), K08AA021745 (PI: Stappenbeck). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

The content of this paper has not been previously published, presented, or posted online.

Birth sex was important for interpretation of alcohol consumption variables. Of 1,877 individuals who were assigned female sex at birth, only 5 participants indicated their current gender identity was male or transgender, a subsample too small to examine in the current study. Thus, analyses focused on cisgender women.

There was a programming error in the RCT-1 minimal assessment condition, such that 35 women who were randomized to this condition were inadvertently directed to view the PNF intervention. These participants were excluded from analyses. An additional 4 participants were excluded due to other programming errors.

Additional models were estimated with Campus (public vs. private) and Study (RCT-1 vs. RCT-2) as covariates, but these were not significant predictors in any model. Thus, the more parsimonious models without Campus or Study are represented here.

Alternate distributions of outcomes were considered. HED frequency was also estimated with MLR as a count variable with a negative binomial distribution and a log link. Blackout frequency was also estimated with MLR as an ordinal, four-category variable. The pattern of all findings was the same, and therefore, the simpler MLR models with continuous outcomes are presented for ease of interpretation and comparability across outcomes.

References

- Barry AE, Chaney BH, Stellefson ML, & Dodd V (2015). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the AUDIT-C among college students. Journal of Substance Use, 20(1), 1–5. 10.3109/14659891.2013.856479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, & Carey KB (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(4), 391–424. 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, & Bradley KA (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Durney SE, Shepardson RL, & Carey MP (2015). Incapacitated and forcible rape of college women: Prevalence across the first year. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(6), 678–680. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, & Goldstein NJ (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Logan DE, & Neighbors C (2010). Which came first: The readiness or the change? Longitudinal relationships between readiness to change and drinking among college drinkers. Addiction, 105(11), 1899–1909. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03064.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189–200. 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, DiBello AM, Meisel MK, Ott MQ, Kenney SR, Clark MA, & Barnett NP (2019). Do misperceptions of peer drinking influence personal drinking behavior? Results from a complete social network of first-year college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(3), 297–303. 10.1037/adb0000455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, & Larimer ME (2012). Brief individual-focused alcohol interventions for college students. In White HR & Rabiner DL (Eds.), College student drinking and drug use (pp. 161–183). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dedert EA, McDuffie JR, Stein R, McNiel JM, Kosinski AS, Freiermuth CE, Hemminger A, & Williams JW Jr. (2015). Electronic interventions for alcohol misuse and alcohol use disorders: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(3), 205–214. 10.7326/M15-0285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, & Carey KB (2012). Optimizing the use of the AUDIT for alcohol screening in college students. Psychological Assessment, 24(4), 954–963. 10.1037/a0028519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, & Marlatt GA (1999). Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donde SD (2017). College women’s attributions of blame for experiences of sexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(22), 3520–3538. 10.1177/0886260515599659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue K, Patton R, Phillips T, Deluca P, & Drummond C (2014). The effectiveness of electronic screening and brief intervention for reducing levels of alcohol consumption: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(6), e142. 10.2196/jmir.3193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson KB, Dunn ME, & Bowers CA (2015). Stand-alone personalized normative feedback for college student drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 2004 to 2014. PLoS ONE, 10(10), 1–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AK, Lewis MA, & George WH (2015). A randomized controlled trial targeting alcohol use and sexual assault risk among college women at high risk for victimization. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 74, 38–49. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AK, Stappenbeck CA, Lewis MA, Granato HF, & Kaysen D (2015). Sexual assault history and its association with the use of drinking protective behavioral strategies among college women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(3), 459–464. 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin MJ, & Read JP (2012). Prospective effects of method of coercion in sexual victimization across the first college year. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(12), 2503–2524. 10.1177/0886260511433518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati NK, Blayney JA, Jaffe AE, Kaysen D, & Stappenbeck CA (2021). A formative evaluation of a web-based intervention for women with a sexual assault history and heavy alcohol use. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Advance online publication. 10.1037/tra0000917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, & Rollnick S (1993). Readiness to Change Questionnaire: User’s manual (revised version). National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre. Technical Report No. 19. https://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/ndarc/resources/TR.019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Armstrong JL, Reed KP, & Cameron AY (2012). Gender differences in sexual assault victimization among college students. Violence and Victims, 27(6), 922–940. 10.1891/0886-6708.27.6.922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC & Sher KJ (1992). Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health, 41(2), 49–58. 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, Blayney JA, Bedard-Gilligan M, & Kaysen D (2019). Are trauma memories state-dependent? Intrusive memories following alcohol-involved sexual assault. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1634939. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1634939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, Bountress KE, Metzger IW, Maples-Keller JL, Pinsky HT, George WH, & Gilmore AK (2018). Student engagement and comfort during a web-based personalized feedback intervention for alcohol and sexual assault. Addictive Behaviors, 82, 23–27. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R (1992). Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Neighbors C, Martell J, Fossos N, & Larimer ME (2006). Incapacitated rape and alcohol use: A prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 31(10), 1820–1832. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Atkins DC, Moore SA, Lindgren KP, Dillworth T, & Simpson T (2011). Alcohol use, problems, and the course of posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective study of female crime victims. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 7(4), 262–279. 10.1080/15504263.2011.620449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(5), 231–244. 10.3109/10673229709030550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, & McCauley JM (2007). Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study (NCJ 219181—Final Report). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Neighbors C, Zheng C, Kenney SR, Napper LE, Walter T, Kilmer JR, Hummer JF, Grossbard J, Ghaidarov TM, Desai S, Lee CM, & Larimer ME (2013). RCT of web-based personalized normative feedback for college drinking prevention: Are typical student norms good enough? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81, 1074–1086. 10.1037/a0034087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Graupensperger S, Lewis MA, Cronce JM, Kilmer JR, Atkins DC, Lee CM, Garberson L, Walter T, Ghaidarov TM, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, & LaBrie JW (2021). Injunctive and descriptive norms feedback for college drinking prevention: Is the whole greater than the sum of its parts? Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer S, Resnick H, Bakanic V, Burkett T, & Kilpatrick D (2010). Forcible, drug-facilitated, and incapacitated rape and sexual assault among undergraduate women. Journal of American College Health, 58(5), 453–460. 10.1080/07448480903540515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Kilmer JR, & Larimer ME (2010). A brief, web-based personalized feedback selective intervention for college student marijuana use: A randomized clinical trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(2), 265–273. 10.1037/a0018859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, & Neighbors C (2004). Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(4), 334–339. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Grills-Taquechel A, & Axsom D (2009). Impaired and incapacitated rape victims: Assault characteristics and post-assault experiences. Violence and Victims, 24(4), 439–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Grills-Taquechel AE, Buck KS, Rosman L, & Dodd JC (2013). Health risk behavior and sexual assault among ethnically diverse women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(1), 7–21. 10.1177/0361684312451842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Kilmer JR, Beck NC, & Zamboanga BL (2010). The efficacy of a targeted personalized drinking feedback intervention among intercollegiate athletes: A randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 660–669. 10.1037/a0020299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, & Miller WR (1979). Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors, 4(1), 55–60. 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, & Kilpatrick DG (2010). Incapacitated, forcible, and drug/alcohol‐facilitated rape in relation to binge drinking, marijuana use, and illicit drug use: A national survey. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 132–140. 10.1002/jts.20489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Ward RM, & Zerubavel N (2013). The role of substance use and emotion dysregulation in predicting risk for incapacitated sexual revictimization in women: Results of a prospective investigation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 125–132. 10.1037/a0031073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Hall N, DiBello AM, Park CJ, Freeman L, Meier E, Leavens ELS, & Leffingwell TR (2020). Depressive symptoms as a moderator of college student response to computerized alcohol intervention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 115, 108038. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler-Kuo M, Dowdall GW, Koss MP, & Wechsler H (2004). Correlates of rape while intoxicated in a national sample of college women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65(1), 37–45. 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan CJ, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, & Murphy JG (2013). The impact of elevated posttraumatic stress on the efficacy of brief alcohol interventions for heavy drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors, 38(3), 1719–1725. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). (2004). NIAAA Council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter, NIH Publication No. 04–5346(3), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, & Larimer ME (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs, 68(4), 556–565. 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, LaBrie J, DiBello AM, Young CM, Rinker DV, … Larimer ME (2016). A multisite randomized trial of normative feedback for heavy drinking: Social comparison versus social comparison plus correction of normative misperceptions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(3), 238–247. 10.1037/ccp0000067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HV, Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Brajcich M, & Larimer ME (2010). Incapacitated rape and alcohol use in White and Asian American college women. Violence Against Women, 16(8), 919–933. 10.1177/1077801210377470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris AL, Carey KB, Walsh JL, Shepardson RL, & Carey MP (2019). Longitudinal assessment of heavy alcohol use and incapacitated sexual assault: A cross-lagged analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 93, 198–203. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai TP, Tahaney K, Winter M, & Saitz R (2016). Readiness-to-change as a moderator of a web-based brief intervention for marijuana among students identified by health center screening. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 161, 368–371. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai TP, Zisserson R, & Saitz R (2011). Using personalized feedback to reduce alcohol use among hazardous drinking college students: The moderating effect of alcohol-related negative consequences. Addictive Behaviors, 36(5), 539–542. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter-Hagene LC, & Ullman SE (2015). Sexual assault-characteristics effects on PTSD and psychosocial mediators: A cluster-analysis approach to sexual assault types. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(2), 162–170. 10.1037/a0037304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter-Hagene LC, & Ullman SE (2018). Longitudinal effects of sexual assault victims’ drinking and self-blame on posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(1), 83–93. 10.1177/0886260516636394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, & DiClemente CC (1986). Toward a comprehensive model of change. In Miller WR & Heather N (Eds.), Treating addictive behaviors: Processes of change (pp. 3–27). New York, NY: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wardell JD, & Colder CR (2013). Reciprocal associations between PTSD symptoms and alcohol involvement in college: A three-year trait-state-error analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(4), 984–997. 10.1037/a0034918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relyea M, & Ullman SE (2015). Measuring social reactions to female survivors of alcohol-involved sexual assault: The Social Reactions Questionnaire – Alcohol. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(11), 1864–1887. 10.1177/0886260514549054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riper H, Blankers M, Hadiwijaya H, Cunningham J, Clarke S, Wiers R, Ebert D, & Cuijpers P (2014). Effectiveness of guided and unguided low-intensity internet interventions for adult alcohol misuse: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 9(6), e99912. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold R, & Hall W (1992). Development of a short ‘readiness to change’ questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. British Journal of Addiction, 87(5), 743–754. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Palfai TP, Freedner N, Winter MR, MacDonald A, Lu J, Ozonoff A, Rosenbloom DL, & Dejong W (2007). Screening and brief intervention online for college students: The iHealth study. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 42(1), 28–36. 10.1093/alcalc/agl092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, Merrick MT, Wang J, Kresnow M, & Chen J (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, & Livingston JA (2010). Alcohol and sexual risk behaviors as mediators of the sexual victimization–revictimization relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 249–259. 10.1037/a0018914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Livingston JA (2018). Women’s alcohol use and risk of sexual victimization: Implications for prevention. In Orchowski LM & Gidycz CA (Eds.), Sexual assault risk reduction and resistance: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 135–172). London, UK: Elsevier, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE (2010). Talking about sexual assault: Society’s response to survivors. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, & Najdowski CJ (2010). Understanding alcohol-related sexual assaults: Characteristics and consequences. Violence and Victims, 25(1), 29–44. 10.1891/0886-6708.25.1.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein-Mah H, Larimer M, Zoellner L, & Kaysen D (2015). Blackout drinking predicts sexual revictimization in a college sample of binge‐drinking women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(5), 484–488. 10.1002/jts.22042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik PW, Culbertson KA, & Sellers K (2000). Readiness to change drinking among heavy-drinking college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61(5), 674–680. 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt DS, Shipherd JC, & Resick PA (2012). Posttraumatic Maladaptive Beliefs Scale: Evolution of the Personal Beliefs and Reactions Scale. Assessment, 19(3), 308–317. 10.1177/1073191110376161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voloshyna DM, Bonar EE, Cunningham RM, Ilgen MA, Blow FC, & Walton MA (2018). Blackouts among male and female youth seeking emergency department care. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(1), 129–139. 10.1080/00952990.2016.1265975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CM (2016). Incorporating expressive writing into a personalized formative feedback intervention to reduce alcohol use among college students [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Houston. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CM, Neighbors C, Dibello AM, Sharp C, Zvolensky MJ, & Lewis MA (2016). Coping motives moderate efficacy of personalized normative feedback among heavy drinking US college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77(3), 495–499. 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]