Abstract

Paris polyphylla Sm. is an important medicinal plant used to treat a variety of diseases through traditional medicine systems such as Ayurveda, Tibetan traditional medicines, Chinese traditional medicines, and others around the world. The IUCN red list has designated it as "vulnerable" due to a decline in wild population by over-exploitation, habitat degradation, illegal collection for trade and traditional use. This review paper aims to summarize the bioactive secondary metabolites in Paris polyphylla. Paris saponins or steroidal saponins are the main bioactive chemical constituents from this plant that account for more than 80% of the total compounds. For instance, polyphyllin D, diosgenin, paris saponins I, II, VI, VII, and H are steroidal saponins having anticancer activity comparable to synthetic anticancer medicines. Antioxidant, anticancer, anti-leishmaniasis, antibacterial, antifungal, anthelmintic, antityrosinase, and antiviral effects of extracts and pure compounds were also demonstrated in vivo and in vitro. In conclusion, this review summarizes the bioactive components from the P. polyphylla which will be useful to researchers and scientists, and for the development of potential drugs.

Keywords: Biological activities, IC50, Paris saponin, Rhizome, Vulnerable

Biological activities; IC50; Paris saponin; Rhizome; Vulnerable.

1. Introduction

Previously, the genus Paris was assigned to the Liliaceae and Trilliaceae families, however in the APG III system, it is assigned to the Melanthiaceae family. Paris includes roughly 24 species found across the world, from Europe to Asia (Zhang et al., 2011). Except for the European P. quadrifolia and the Caucasian P. incompleta, practically all of the 24 species are restricted to East Asia (19 species in China) (Ji et al., 2006). Paris has 27 species globally, including 22 species and 12 endemic species in China (Cunningham et al., 2018); 33 species, and 15 varieties in Southwest China (Ding et al., 2021). The World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP) listed 32 Paris species and 8 varieties of P. polyphylla in 2020. P. polyphylla has four subspecies and one variety in Nepal (www.eFloras.org, 2/4/2021). The Department of Plant Resources, Government of Nepal (DPR, 2017) has classified P. polyphylla as a "medicinal plant prioritized for agrotechnology development". It is distributed from sub-tropical to sub-alpine regions in various parts of the world (IUCN, 2004; Cunningham et al., 2018). In Nepal, it is distributed within an altitudinal range of 1500–3500 m from west to east (IUCN, 2004; Kunwar et al., 2020). It is known as ‘Satuwa’ in Nepali, ‘Paris root’ in English, and ‘Haimavati’ in Sanskrit. The rhizomes are used in traditional medicine known as ‘Rhizoma Paridis’ in Chinese Pharmacopoeia (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2015).

Paris polyphylla (Figure 1) flourishes on thickets, grassy or rocky slopes of damp, humus, nitrogen and phosphorus rich soil under the canopy of the forest (Paul et al., 2015; K.C. et al., 2010; Deb et al., 2015). It grows in undisturbed areas with a canopy cover of more than 80% (Deb et al., 2015). The wild population of P. polyphylla is declining due to habitat destruction, deforestation, over-exploitation, illegal collection and harvesting, and has listed as "vulnerable" in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Chauhan, 2020). Overharvesting mainly during the season earlier than seed maturation may result in infrequent seed formation and germination that appears to be a severe threat to plant regeneration (Negi et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Photographs of aerial parts and rhizomes of P. polyphylla.

The rhizome and other parts of P. polyphylla in the form of infusions, juices, powders and pastes have been used in the traditional medicine to treat cuts, wounds, blisters, scabies, rashes or itching, burns, sprain, headache, fever, anthelmintic, vermifuge, expectorant, antispasmodic, digestive, gastritis, diarrhoea, dysentery, menstruation pain, tonic, antidote of poison (aconite poisoning), antidote of poisonous insects and snake, antiseptic, jaundice, vasoconstriction in the kidney, vasodilation in spleen and limbs (Liang, 2000; Rajbhandari, 2001; Manandhar, 2002; DOA, 2003; IUCN, 2004; Bhattarai et al., 2006; Kunwar et al., 2006; Baral and Kurmi, 2006; Dutta, 2007; K.C. et al., 2010; Acharya, 2012; Jamir et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2012; Luitel and Pathak, 2013; Lamichhane et al., 2014; Deb et al., 2015). P. polyphylla is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for the treatment of boils, venomous snake bites, carbuncles, sore throat, and traumatic discomfort (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2015). The main raw material for 'Yunnan Baiyao' and 'Gong Xue Ning (GXN) capsule' is a rhizome of this plant. Back discomfort, bleeding, shattered bones, wound healing, pain, fungal illnesses, poisonous snakes or bugs bites, skin allergy, tumours, and a variety of disease conditions are treated with the 'Yunnan Baiyao' (Long et al., 2003). GXN capsules were developed in China using the saponin extract of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis to treat abnormal uterine bleeding (Zhao and Shi, 2005; Guo et al., 2008). It is also a source for "Jidesheng Sheyaopian" a Chinese patent medicine. The objective of this review paper is to summarize the biological activities of the components of P. polyphylla.

2. Method

Research articles published between 1990 and 2021 on secondary metabolites and their biological activities of Paris polyphylla were accessed through Google Scholar, PubMed and ProQuest using phrases "Paris polyphylla secondary metabolites", "anticancer activity of Paris polyphylla", "antimicrobial activity of Paris polyphylla", "antioxidant activity of Paris polyphylla" and "anthelmintic activity of Paris polyphylla". This review does not include articles from conference proceedings and those written in languages other than English.

3. Bioactive compounds of Paris polyphylla

Terpenes, alkaloids, glycosides, phenolics, volatile oils, terpenoids, saponins, steroids and resins are active secondary metabolites found in medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) (Dubey, 1993; Ramawat and Goyal, 2004). Secondary metabolites of MAPs are used in drugs, perfumes, agrochemicals, flavouring agents and pigments (Ramawat and Goyal, 2004; Chawla, 2014). The existence of secondary metabolites in MAPs confers therapeutic properties, the majority of which likely originated as chemical defences against predation or infection. Because of the structural diversity of secondary metabolites and the wide spectrum of pharmacological activity, MAPs are regarded as excellent sources of novel pharmaceutical medicines (Pant, 2014).

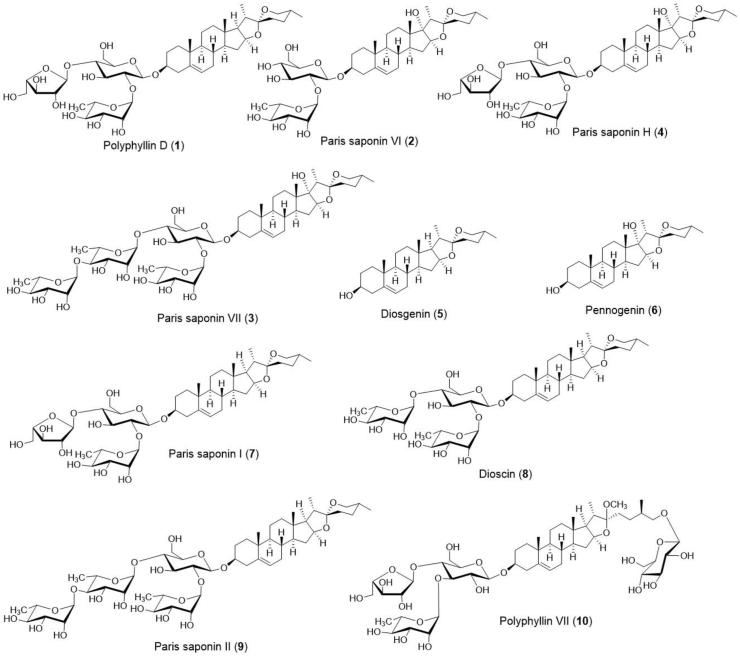

Various compounds have been isolated and characterized from the rhizomes, roots, aerial stem and leaves of P. polyphylla including steroidal saponins (Buckingham, 1994; Wang et al., 2005; Devkota et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012a; Li et al. 2012, 2013), flavonoid glycosides (Chen et al., 1995; Kang et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012a), sterols (Chen et al., 1990; Wu et al., 2012a), triterpenoid saponins (Wu et al., 2012b) and polysaccharides (Zhou and Yang, 2003). From 1960 to 2010, more than 90 components were isolated, including steroidal saponins, phytosterols, flavones, and phytoecdysones (Zhang et al., 2011), and about 67 steroidal saponins were isolated from 11 species of the genus Paris (Huang et al., 2009). Till 2020, around 320 chemical components have been isolated, including steroidal saponins, C-21 steroids, phytosterols, insect hormones, pentacyclic triterpenes, flavonoids, and other chemical substances (Ding et al., 2021). More than 50 paris saponins have been identified from P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2015), however, only four paris saponins; paris saponins I, II, VI and VII have been officially recognized as quality standard components of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (Qin et al., 2018). Saponins are a type of glycoside consists of aglycones (water-insoluble) such as steroids or triterpenoids, as well as one or more sugar chains (water-soluble) such as glucose, galactose, pentose, or methyl pentose. Saponins have their aglycons constituents which are mainly diosgenin, pennogenin, 24-hydroxy pennogenin, 27-hydroxy pennogenin, 23, 27-dihydroxy pennogenin, 25S-isonuatigenin, nuatigenin, and C-21 steroidal saponins. Saponins in plants have diverse structures due to the presence of different sugars at different locations and orientations. Antitumor, anti-oxidative characteristics, expectorants, inhibition of platelet aggregation, insecticidal, antidiabetic, antifungal/anti-yeast, antiparasitic, antibacterial, antihyperlipidemic, and anti-inflammatory qualities are just a few of the therapeutic applications of steroidal saponins (Sparg et al., 2004). Structures of some of the main compounds are represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of the major compounds of Paris polyphylla.

Wang et al. (2005) isolated two new and six known compounds from the rhizome of P. polyphylla, including falcarindiol, β-ecdysterone, pennogenin-3-O-α-L-arabinofuranosyl (1→4)-β-D-glucopyranoside, pennogenin-3-O-α-L-arabinofuranosyl (1→4)-[ α-L-rhamnopyranosyl (1→2)]-β-D-glucopyranoside, diosgenin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, diosgenyl-3-O-α-L- rhamnopyranosyl (1→4)-β-D-glucopyranoside, diosgenin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl (1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, & diosgenin-3-O -α-L-rhamnopyranosyl (1→4)-[ α-L-rhamnopyra nosyl (1→2)]-β-D-glucopyranoside. Devkota et al. (2007) isolated four known compounds from the rhizomes of P. polyphylla collected from Parbat district, Nepal, viz: przewalskinone B, polyphyllin C, polyphyllin D and dioscin. Xiao et al. (2009) isolated five paris saponins: paris saponin I (PSI), paris saponin V (PSV), paris saponin VI (PSVI), paris saponin VII (PSVII) and paris saponin H (PSH). The rhizome contains pariphyllin A, pariphyllin B, paristerone, polyphyllin D, and trillin (Buckingham, 1994). Li et al. (2013) also isolated nine steroidal saponins, viz. PSI, PSII, PSV, PSVI, PSVII, PSH, dioscin, gracillin and PGRR from the rhizome of P. polyphylla. Kang et al. (2012) isolated three new steroidal saponins; parisyunnanosides G−J, and three known compounds; padelaoside B, pinnatasterone and 20-hydroxyecdyson from the rhizomes of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis. According to Li et al. (2012), P. polyphylla is an important medicinal plant containing saponin steroids polyphyllin D, dioscin and balanitin-7.

Wu et al. (2012a) isolated eighteen steroidal saponins and sterol from the rhizome of P. polyphylla, viz. pariposide A, pariposide B, pariposide C, pariposide D, pariposide E, pariposide F, (3β,25R)-spirost-5-en-3-ol 3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyrano side, (3β,25R)-spirost-5-en-3-ol3-O-β-Dglucopyranosyl-(1→6)-glucopyranoside, (3β,25R)-spirost-5-en-3-ol3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 →2)]-β-D-gluco pyranoside, (3β,25R)-spirost-5-en-3-ol-3-O-αyranosyl-(1→4)-α-L-rhamnopy ranosyl-(1→4)-β-D-glucopyranoside, (3β,25R)-spirost-5-en-3-ol-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)]-β-D-glucopyranoside, (3β,17α, 25R)-spirost-5-ene-3,17-diol 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, (3β,17α,25R)-spirost-5-ene-3,17-diol-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D glucopyranoside, (3β,17α,25R)-spirost-5-ene-3,17-diol-3-O-α-L-arabinofuranosyl-(1→4)-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)]-β-D-glucopy ranoside, (3β, 22E)-stigmasterol-5,22-dien 3-O-β-D-gluco pyranoside, β-daucosterol, 24-epi-pinnatasterone and 20-hydroxyecdyson. Wu et al. (2012b) also isolated six new oleanane-type triterpenoid saponins from the rhizome of P. polyphylla; paritrisides A-F along with nine known triterpenoid saponins; paritriside A, paritriside B, paritriside C, paritriside D, paritriside E, paritriside F, 3β-hydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oicacid3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-L-arabinopyranoside, 3β-hydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oicacid 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-xylopyranoside, 3β-hydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oic acid 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside, 3β-hydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oic acid 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside, 3β-hydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oic acid 3-O-β-D-glucuronide, 3β-hydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oicacid 3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3β-hydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oic acid 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3β,23-dihydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oic acid 3-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-L-arabinopyranoside, and 3β,23-dihydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oic acid3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-L-arabinopyranoside.

4. Biological activities of the secondary metabolites

Chemical components of P. polyphylla have anticancer, antioxidant, anti-leishmanial, anthelmintic, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-gynaecological disease, antiviral, and antityrosinase properties (Tables 1 and 2). The biological activity of components was examined against cancer cell lines, bacteria, enzymes and other parasites in the form of crude extract, a mixture of compounds (steroidal saponins), or pure compounds.

Table 1.

Biological activity of some important isolated compounds of Paris polyphylla.

| Compound name | Biological activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Polyphyllin D (1) |

Breast cancer:In vitro: Induced apoptosis in estrogen-sensitive MCF-7 and estrogen-insensitive MDA-MB-231 cells with IC50 of 5 μM and μ2.5 M, respectively. In vivo: Reduced tumour growth by 50% in nude mice carrying MCF-7 cells at 2.73 mg/kg body weight. |

Lee et al. (2005) |

| Ovary cancer:In vitro: Anti-proliferative effects against SKOV3, A2780CP, A2780S, M41, M41-R, TYKNU, TYKNU-R, OVCAR8, HAYA8, OVCAR5, MCAS, PEO1, IGR-OV1, IMCC5, OVCAR2, OVCA420, OVCA432, OVCA433, TOV-112D cell lines with IC50 ranging from 0.2 to 1.4 μM. | AlSawah et al. (2015) | |

| Leukaemia:In vitro: Induced apoptosis in the human erythroleukemia cell line (K562) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with an IC50 of 0.8 ± 0.1 μM. | Yang et al. (2016) | |

| Anthelmintic activity:In vivo: Inhibited the activity of Dactylogyrus intermedius (a freshwater fish ectoparasite) with EC50 of 0.70 mg/L, which was higher than of the mebendazole (EC50 = 1.25 mg/L). | Wang et al. (2010) | |

| Leukaemia:In vitro: Induced apoptosis in drug-resistant K562/A02 human leukaemia cells, with an IC50 of 0.9 μM in K562 cells and 0.8 μM in K562/A02 cells, respectively. | Wu et al. (2013) | |

| Hepatocellular cancer:In vitro: Induced apoptosis in the HepG2 and R-HepG2 liver cancer cell lines with the IC50 of 7μM and 5μM, respectively, compared to Cisplatin (50μM and 167μM) and Taxol (20μM and 50μM). | Cheung et al. (2005) | |

| Brain tumour:In vitro: Induced apoptosis in U87 human glioma cells with an IC50 of 4.94 × 10−5 M. | Yu et al. (2014) | |

|

Antiangiogenesis in the tumour:In vitro: Decreased endothelial cell migration and capillary tube formation at 0.3 μM and 0.4 μM in a human microvascular endothelial cell line (HMEC-1HMEC-1 cells). In vivo: Induced 70% abnormalities in intersegmental vessel formation (ISV) in zebrafish embryos at doses of 0.156 μM and 0.313 μM. |

Chan et al. (2011) | |

| Paris saponin VI (PSVI) (2) | Hepatocellular toxicity:In vitro: Induced apoptosis in HL-7702 and HepaRG cell lines with IC50s of 8.18 μM and 6.65 μM, respectively. | Wang et al. (2019) |

|

Lung cancer:In vitro: PSVI triggered apoptosis in lung cancer cells (A549 and NCI–H1299) with IC50 of 4.53 ± 0.56 μM in A549 cells and 5.46± 0.45 in NCI–H1299 cells after 48 h. In vivo: In nude mice bearing A549 tumour xenografts, tumour inhibitory rates of PSVI in A549 cells were 25.74%, 34.62.71%, and 40.43% at 2, 3, and 4 mg/kg, respectively. |

Lin et al. (2015) | |

| Brain cancer:In vitro: PSVI induced apoptosis in glioma cell lines (U251, U343, LN229, U87, and HEB) with IC50 value of 3.65 ± 0.428 μM in LN229 cells, 5.00 ± 0.372 μM in U87 cells, 5.13 ± 0.528 μM in U251 cells, and 3.99 ± 0.397 μM in U343 cells after 24 h. After treatment with PSVI, normal HEB cells showed only minor cytotoxicity. | Liu et al. (2020) | |

| Paris saponin VII (PSVII) (3) | Human cervical cancer:In vitro: Induced apoptosis in human cervical carcinoma Hela cells with an IC50 of 2.62 ± 0.11 μM, When cells were exposed to 0.8, 1.6, and 2.4 μM of PSVII for 24 h, the proportion of apoptotic cells was 10.50%, 17.37%, and 38.60%, respectively. | Zhang et al. (2014) |

| Ovary cancer:In vivo: Inhibited the growth of SKOV3/DDP cells, increased caspase-3 5.71 times and 11.06 times, and reduced Bcl-2 expression 33.3% and 61.1% in 48 and 24-hour groups of PSVII (50 μM/L and 100 μM/L), respectively. Silica nanocomposite also inhibited the growth of SKOV3/DDP cells. | Yang et al., (2015b) | |

| Hepatocellular toxicity:In vivo: Induced apoptosis in HL-7702 and HepaRG cells with IC50s of 0.80 and 2.75 μM, respectively. | Wang et al. (2019) | |

| Liver cancer:In vivo: HepG2/ADR cells and HepG2 cells treated for 48 h with PSVII (0.88, 1.32, 1.98, and 2.97 μM) had a higher apoptosis rate or a lower ADR (a chemotherapy drug) IC50. Those treated with PS VII (≤1.98 μM) and ADR (5 nM) showed increased ADR accumulation, decreased drug-resistant gene expressions, and increased cell apoptosis. | Tang et al. (2019) | |

| Paris saponin H (PSH) (4) |

Hepatocellular carcinoma:In vitro: Lowered cell viability in PLC/PRF/5 and Huh7 cells at 1.25–20 μM, increased apoptosis at 1.25 μM, and elevated caspase-3 at 2.5, 5.0, and 10 μM. In vivo: Inhibited tumour growth in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) xenograft model of nude mice, at doses of 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg of PSH |

Chen et al. (2019) |

| Diosgenin (5) | Anthelmintic activity: In vivo: Inhibited the activity of Dactylogyrus intermedius with EC50 of 0.44 mg/L. It was more efficacious than mebendazole (EC50 = 1.25 mg/L). | Wang et al. (2010) |

|

Lung cancer:In vitro: Induced apoptosis in the lung adenocarcinoma cell line (LA795) from mice with an IC50 of 149.75 ± 10.43 μM/L after 24 h. In vivo: Decreased tumour growth in T739 mice with LA795 lung adenocarcinoma by 33.94% with oral treatment, but Cyclophosphamide (a chemotherapy drug) decreased tumour development by 56.09%. |

Yan et al. (2009) | |

| Pennogenin (6) |

Hepatocellular cancer:In vitro: Inhibited the growth of HepG2 cells with IC50 values from 9.7 μM to 13.5 μM. Antifungal activity:In vitro: Inhibited the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisae hansen with MIC values from 0.6 mg/mL to 2.5 mg/mL. The MIC values of the compound against Candida albicans were from 0.6 mg/mL to 1.2 mg/mL. |

Zhu et al. (2011) |

| Paris saponin I (PSI) (7) | Lung cancer:In vitro: PSI combined with hyperthermia at 43 °C induced apoptosis on a non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) PC 9 cell line with IC50 of 1.21 μg/mL. When compared to the PSI alone, the percentage of cells in the G2/M phase arrest increased from 33.59 to 42.58%. | Zhao et al. (2015) |

| Human gastric cancer: In vitro: PSI sensitized the human gastric cancer cell line (SGC-7901) to the cisplatin with minimal damage. PSI had an IC50 of 1.12 μg/mL in SGC-7901 cell lines after 48 h at 0.2–6.4 μg/mL. Cisplatin had an IC50 of 30.4 μM in SGC-7901 cell lines after 48 h at 1–64 μM concentration. The IC50 of Cisplatin was reduced to 20.3 μM when it was coupled with PSI (0.3 μg/mL). | Song et al. (2016) | |

|

Ovarian cancer:In vitro: PSI induced apoptosis in SKOV3 cells with an IC50 of 15 μM/L & in a mouse model of human ovarian cancer. In vivo: In a subcutaneous xenograft mouse model, PSI treatment at 15 and 25 mg/kg inhibited the growth of SKOV3 cells by 38 and 66%, respectively. |

Xiao et al. (2009) | |

| Hepatocellular toxicity:In vitro: PSI induced apoptosis in HL-7702 and HepaRG cells, with IC50s of 0.84 and 4.66 μM, respectively, at 24 h. | Wang et al. (2019) | |

|

Lung cancer:In vitro: PSI triggered apoptosis in the gefitinib-resistant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell line PC 9 ZD with IC50s of 2.51, 2.07, and 1.53 μg/mL after 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation. In vivo: The 18F fludeoxyglucose microPET scan for glucose metabolic activity in tumours in xenograft nude mice revealed a lower tumour SUV in the PSI treatment groups compared to the control group. |

Jiang et al., (2014a) | |

| Lung cancer:In vitro: With an IC50 of 2.5132 μg/mL, PSI reduced the proliferation of gefitinib-resistant lung cancer cell line (PC9ZD cells) over 24 h. | Jiang et al., (2014b) | |

| Lung cancer:In vitro: PSI reduced the proliferation of three non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells (H1299, H520, H460) and one small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cell (H446). PSI at 4 mM caused early-stage apoptosis in H1299 and H520 cells, with the latter reaching a high of 73.54 ± 3.44%. However, at 4 mM, the H446 cells went into late-stage apoptosis. | Liu et al. (2016) | |

| Liver cancer:In vivo and in vitro: PSI reduced vasculogenic mimicry (VM) production in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines (SMMC7721, PLC, HepG2, Hep3B, and Bel7402), as well as transplanted hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Patients with HCC who were given PSI before surgery had lower microvessel density (MVD) and VM than those who were not. | Xiao et al. (2018) | |

| Liver cancer:In vitro: PSI (at 0.5–2 μg/mL) sensitized HepG2 cells to cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity after 24 h of treatment with 0.2–100 μM cisplatin. | Han et al. (2015) | |

| Bone tumour:In vitro: PSI induced apoptosis at 0–2.5 μM in MG-63, Saos-2, and U-2 OS human osteosarcoma cells. | Chang et al. (2015) | |

| Lung cancer:In vitro: PSI caused apoptosis in the cisplatin-resistant human non-small cell lung cancer cell line (A549/DDP) with an IC50 of 1.54 ± 0.26 μM/mL in the A549 and 1.08 ± 0.20 μM/mL in the A549/DDP cell lines. | Feng et al. (2019) | |

| Dioscin (8) | Anthelmintic activity:In vivo: Dioscin had a substantial EC50 of 0.44 mg/L against Dactylogyrus intermedius (a freshwater fish ectoparasite), which was higher than the mebendazole (EC50 = 1.25 mg/L). | Wang et al. (2010) |

| Paris saponin II (PSII) (9) | Lung cancer:In vitro: PSII promoted apoptosis in human lung cancer cells (NCI–H460 and A549) as soon as 2 h after 1 μM treatment, but did not affect normal human pulmonary epithelial cells (BEAS-2B). The production of cytoplasmic acidic vesicular organelles (AVOs) was reduced and apoptosis was promoted in NCI–H460 cells treated with 1 μM PSII in the presence or absence of 10 mM CQ over 24 h. | Zhang et al., 2016a, Zhang et al., 2016b |

| Hepatocellular toxicity:In vitro: PSII induced apoptosis in HL-7702 and HepaRG cells, with IC50s of 1.88 and 3.74 μM, respectively. | Wang et al. (2019) | |

|

Ovary cancer:In vivo: PSII induced apoptosis in human ovarian cancer cells (OC SKOV3 and OC HOC-7) with lower IC50s of 7.17 μM and 6.44 μM, respectively, when compared to VP16 (chemotherapy drug) with higher IC50s of 14.67 μM and 6.44 μM, respectively. In vivo: PSII inhibited primary human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) proliferation, angiogenesis of rat aortic rings, tumour growth, and angiogenesis in an ovarian cancer tumour xenograft mouse model. |

Xiao et al.(2014) | |

|

Ovary cancer:In vitro: PSII inhibited more human ovary cancer SKOV3 cell proliferation than VP16-etoposide (a chemotherapy drug) treatment at the same dose and time point, with lower IC50s (20.99, 10.44, 8.83, and 6.98 μM, days 1–4, respectively) than VP16 (82.04, 17.18, 11.80, and 8.01 μM, days 1–4). In vivo: In a xenograft mouse model of ovarian cancer, the combination of PSII therapy and constitutive inhibition of IĸBα activity inhibited the development of human ovarian cancer cells significantly. |

Yang et al., (2015a) | |

| Colorectal cancer:In vitro: PSII induced apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cell lines (HT 29 and HCT 116) with an IC50 of 1.89 μM in HT 29 cells and 2.43 μM in HCT 116 cells, respectively. PSII, on the other hand, showed an IC50 of 18.96 μM in human colonic epithelial cells (HcoEpiC), about 10 times higher than in colon cancer cells. | Chen et al. (2018) | |

|

Ovarian cancer cells:In vitro: PSII had a 90.0% inhibition index after 7 days of therapy at 10 μM, compared to PSI (80.3%) and the etoposide (69.2%) in the human ovarian cancer cell line (SKOV3). On PS II-treated SKOV3 cells, the IC50 and total growth-inhibiting concentration (TGI) were 2.4 μM and 6.3 μM, respectively, compared to PSI (3.1 μM and 9.3 μM) and etoposide (3.2 μM and 9.7 μM). In vivo: In human SKOV3 ovarian cancer xenografts in athymic mice, intraperitoneal administration of PSII and PSI at 15 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg doses inhibited tumour growth by 46% and 70%, and 40% and 64%, respectively. |

Xiao et al. (2012) | |

| Polyphyllin VII (PPVII) (10) | Hepatocellular carcinoma:In vitro: PPVII induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells with IC50 of 1.32 μM, 0.85 μM, 0.78 μM at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. Other hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (Hep3B, Bel7402, and 7721) also induced cytotoxicity with IC50 of 2.61 μM, 2.86 μM, and 2.30 μM, respectively, after 24 h. | Zhang et al., 2016a, Zhang et al., 2016b |

| Lung cancer:In vitro: PPVII induced apoptosis in A549 human lung cancer cells with an IC50 of 0.41 ± 0.10 μM after 24 h. | He et al. (2020) | |

|

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma:In vitro: PPVII triggered apoptosis in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cell lines such as HONE-1 and NPC-039 cells with IC50s of 2.33 ± 0.22 μM and 2.30 ± 0.31 μM, respectively. In vivo: PPVII inhibited tumour growth in NPC carcinoma xenograft model mice. |

Chen et al. (2016) | |

| Lung cancer:In vitro: PPVII induced apoptosis and autophagy in the cisplatin (DDP)-resistant human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell line (A549/DDP), with an IC50 of 2.26 ± 0.30 μM/mL in the A549 and 1.84 ± 0.23 μM/mL in the A549/DDP cell lines. | Feng et al. (2019) | |

|

Lung cancer:In vitro: PPVII triggered apoptosis in lung cancer cells such as A549 and NCI–H1299 cells, with an IC50 of 1.59 ± 0.12 μM in A549 cells and 1.87 ± 0.09 in NCI–H1299 cells at 48 h. In vivo: In Nude mice bearing A549 tumour xenografts, tumour inhibitory rates of PSVII in A549 cells were 25.63%, 41.71%, and 40.41% at 1, 2, and 3 mg/kg respectively. |

Lin et al. (2015) | |

| Brain cancer:In vitro: PPVII triggered apoptosis in glioma cell lines such U87-MG and U251 cells with IC50 of 4.24 ± 0.87 μM and 2.17 ± 0.14 μM respectively. PPVII (at 0.4 μM) and TMZ (a chemotherapy drug) boosted cytotoxicity in U251 cells and at 0.8 μM in U87-MG cells, indicating that even low concentrations of PPVII can increase TMZ cytotoxicity. | Pang et al. (2019) |

Table 2.

Biological activity of crude extracts of Paris polyphylla.

| S.N. | Extract | Source | Biological Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Methanol extract | Rhizome |

Lung cancer:In vivo: The extract (2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 mg/kg) inhibited tumour growth, volume, and weight in Lewis bearing-C57BL/6 mice at a rate of 26.49 ± 17.30%, 40.32 ± 18.91%, and 54.94 ± 16.48%, respectively. In vitro: The extract (0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 mg/mL) induced apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell lines. |

Li et al. (2013) |

|

Antioxidant activity:In vitro: Methanol extracts of rhizomes collected from two places Tholung (PPT) and Uttaray (PPU) showed free radical scavenger of DPPH with an IC50 of 2.01 μg/mL and 2.55 μg/mL, respectively. PPT had an IC50 of 2.22 μg/mL and PPU had an IC50 of 2.57 μg/mL, according to the ABTS test. Cytotoxicity on HeLa, HepG2, and PC3: In vitro: Methanol extracts inhibited HeLa cell (cervical cancer cell) growth >90% at 100 μg/mL. PPT and PPU both had a moderate effect on HepG2 cells (non-tumorigenic hepatic cells) growth up to 30 μg/mL concentration, whereas PPT inhibited growth by 73.47% at 100 μg/mL concentration. Both extracts inhibited PC3 (prostate cancer cell line) cells at a dosage of 100 μg/mL. |

Lepcha et al. (2019) | |||

|

Antioxidant activity:In vitro: Methanol extract has a stronger antioxidant activity with an IC50 of 1.09 mg/mL. Antimicrobial activity:In vitro: At 5 mg/mL, methanol extract inhibited the growth of Aspergillus niger (97.74%), Staphylococcus aureus (95.58%), Escherichia coli (95.58%), and Trichoderma reesei (74.41%). The antifungal activity was best against A. niger, with a zone of inhibition diameter of 33 mm, and lowest against T. reesei, with a zone of inhibition diameter of 31 mm. The antibacterial activity was best against E. coli, with a zone of inhibition diameter of >31 mm. |

Mayirnao and Bhat (2017) | |||

| Anthelmintic activity:In vivo: With an EC50 of 18.06 mg/L, methanol extract exhibited substantial efficacy against Dactylogyrus intermedius (a freshwater fish ectoparasite). | Wang et al. (2010) | |||

| Leaves | Antiviral activity:In vitro: With an IC50 of 8.74 μg/mL and a SI/selectivity index (CC50/EC50) of 1.75, methanol extract exhibited antiviral activity against Chikungunya virus (CHIKV). | Joshi et al. (2020) | ||

| Antifungal activity:In vitro: At 1000 μg/mL, methanol extract inhibited the growth of Candida albicans (99 % inhibition). | ||||

| Antibacterial activity:In vitro: At 1000 μg/mL, methanol extract inhibited the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (100%), Staphylococcus aureus (80%), Listeria innocua (65%), Escherichia coli (57%), Salmonella enteric (67%), and Shigella sonnei (47%). | ||||

| 2. | Dichloromethane and methanol extract | Rhizome | Bone cancer: Dichloromethane extracts induced apoptosis in SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells with an IC50 of 9.74 ± 0.36 μg/mL, but had a less effect on the percentage of viability and necrosis of normal canine primary chondrocyte cells (IC50 of 382.70± 8.20 μg/mL). In both primary chondrocytes and SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells, methanol extract showed the lowest IC50 of <10 μg/mL. | Ruamrungsri et al. (2016) |

| 3. | Ethanol extract | Roots | Human oesophagal cancer cells: In vitro: ethanol extract induced apoptosis at 25 mg/mL, 50 mg/mL, 100 mg/mL, and 200 mg/mL concentrations, and increased the expression of the cancer suppressor gene (connexin26) at the mRNA and protein levels in oesophagal cancer ECA109 cells. | Li et al. (2012) |

| Rhizome | Antioxidant activity:In vitro: The total phenol concentration was 0.68 mg/g catechol and 0.47 mg/g catechol with the ethanol and petroleum ether extracts respectively by Folin's Ciocalteu reagent, and the inhibitory concentration value of ethanol extract was 68 μg/mL (ascorbic acid 7.8 μg/mL). It means that the ethanol extract has a larger total phenolic content and, as a result, has more antioxidant activity. | Devi et al. (2018) | ||

| Antifungal activity:In vitro: Ethanol extract showed antifungal activity on Cladosporium cladosporioides. | Deng et al. (2008) | |||

| Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB):In vitro: Using myometrial strips from estrogen-primed or pregnant rats, ethanol extract increased the frequency and intensity of phasic myometrial contractions with 23.19 ± 0.27% of the potassium response, and the EC50 of 19.82 ± 0.42 mg/mL. | Guo et al. (2008) | |||

| Stem | Digestive cell cancer:In vitro: The six human digestive tumour cell lines (SMMC-7721, HepG-2, BGC-823, SW-116, LoVo, and CaEs-17) demonstrated apoptosis with IC50s ranging from 10 to 30 μg/mL. The two liver cancer cell lines, SMMC-7721 and HepG-2, showed the lowest IC50 of 12 μg/mL and 10 μg/mL, respectively. | Sun et al. (2007) | ||

| Leaves | Lung cancer:In vitro: ethanol extract inhibited the growth of A549 human lung cancer cells, that was 47.76 %, 50.24 %, 53 %, and 64.17 % at 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL, respectively. | Hu et al. (2017) | ||

| Whole plant | Human prostate cancer:In vitro: PPEE induced apoptosis in PC3 and DU145 prostate cancer cells, with IC50 values of 3.98 μg/mL and 8 μg/mL, respectively. Cisplatin (a positive control) inhibited prostate cancer cell viability more effectively than PPEE. In vivo: In BALB/c nude mice, PPEE at 100 mg/kg resulted in a tumour volume of 333.01 ± 34.77 mm3, representing a 51.05% inhibition rate in PC3 xenograft development. | Zhang et al. (2018) | ||

| Bladder cancer:In vitro: Ethanol extracts induced apoptosis on bladder cancer cells with mutant p53, such as HT1197 and J82 cells, with an IC50 of 1.2 μg/mL, comparable to the action of cisplatin (chemotherapy drug). | Guo et al. (2018) | |||

|

Colon, lung, liver, leukaemia & breast cancer:In vitro: TSSAPs had IC50s ranging from 8.12 to 12.61 μg/mL, while TSSRs had IC50s ranging from 1.75 to 6.62 μg/mL in five tumour cell lines (human leukaemia: HL-60, human lung cancer: A-594, human liver cancer: SMMC-7721, human breast cancer: MCF-7, and human colon cancer: SW480). With IC50s of 1.75 and 3.49 μg/mL, TSSRs showed high cytotoxicity against A549 and SW480 cells, respectively. Antimicrobial activity:In vitro: TSSAPs and TSSRs inhibited the growth of E. coli, Candida albicans (5314), and Candida albicans (Y0109) with MIC values of 156, 5.15, and 10.3 g/mL, respectively. |

Qin et al. (2018) | |||

| 4. | Chloroform, ethyl acetate, and butanol extracts | Rhizome | Tyrosinase enzyme: All the extracts showed mild to moderate inhibitory potentials against the enzyme tyrosinase. | Devkota et al. (2007) |

| 5. | Paris polyphylla steroidal saponins (PPSS) | Rhizome and Root | Lung cancer:In vitro: PPSE at 0, 20, 40, and 80 mg/L induced apoptosis in human lung cancer A549 cells with IC50 values of 72.55, 49.96, and 21.01 mg/L at 12, 24, and 48 h, respectively. | He et al. (2014) |

4.1. Anticancer activity

Cancer is a non-communicable disease in which some of the body's cells grow out of control, resulting in malignant tumours that spread to other regions of the body via metastasis. The rate of cell division and cellular attrition determine the proliferation of cancer cells. The rate of cell growth in cancer cells is uncontrolled resulting in tumour invasion. Due to its high mortality rate, cancer is a severe problem in both developed and developing countries. According to the American Cancer Society, there were 1,762,450 new cancer cases and 606,880 cancer deaths in the United States in 2019 (Siegel et al., 2019). As a result, several anticancer drugs must be used to drive cancer cells apoptosis. In the short term, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy are successful for certain individuals, but they come with a slew of side effects, including toxicity, tumour spread and a high rate of tumour recurrence (Song et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018). Chemotherapy has several drawbacks including multidrug resistance and significant dose-related toxicity limit its practical application (Han et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2019). There is a pressing need to find more effective and less hazardous anticancer drugs. Many clinically utilized cancer chemotherapy drugs are derived from natural products, which are still hotspots for innovative lead discovery (Newman and Cragg, 2012).

Methanol, ethanol, petroleum ether, water and dichloromethane extracts as well as steroidal saponins obtained from various parts of P. polyphylla such as the rhizome, root, leaves, stem and whole plant have shown anticancer activity against lung cancer (Yan et al., 2009; Li et al., 2013; He et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2018), oesophagal cancer (Li et al., 2012), bone cancer (Ruamrungsri et al., 2016), prostate cancer (Zhang et al., 2018), breast cancer (Qin et al., 2018), bladder cancer (Guo et al., 2018), liver cancer (Qin et al., 2018), colon cancer (Qin et al., 2018) and digestive cell cancer (Sun et al., 2007). Methanol extract had the lowest IC50 of <10 μg/mL in both chondrosarcoma cell lines and normal canine primary chondrocyte cells (Ruamrungsri et al., 2016). Similarly, ethanol extract had IC50 ranging from 10 μg/mL to 30 μg/mL than the aqueous extracts on the six human digestive tumour cell lines (Sun et al., 2007). Ethanol extracts induced an anti-tumour response in vivo in PC3 xenograft development in BALB/c nude mice, in which the highest dose exhibited an effect similar to that of 5-FU (positive control) (Zhang et al., 2018). Saponins can cause cell death in a variety of ways including programmed (apoptosis and autophagy) and non-programmed routes (Escobar-Sá nchez et al., 2015). Total saponins, on the other hand, were found to be cytotoxic against five cancer cell lines (human leukaemia, lung cancer, liver cancer, breast cancer and colon cancer) (Qin et al., 2018). They were utilized as agents to limit cell proliferation and necrotic induction since their effect on tumour cells was assessed with a lower IC50.

Similarly, pure compounds extracted from P. polyphylla were found to have anticancer properties against a variety of cancer cells. Polyphyllin D was the most frequently studied steroidal saponin for cancer treatment and it was found to have the activity against breast cancer (Lee et al., 2005), ovary cancer (AlSawah et al., 2015), leukaemia (Yang et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2013), liver cancer (Cheung et al., 2005), brain tumour (Yu et al., 2014) and antiangiogenesis in the tumour (Chan et al., 2011). In cancer cell lines, it works as a strong anticancer agent in vitro with a lower IC50 ranging from 0.2 to 1.4 μM in ovary cancer cells (AlSawah et al., 2015), 0.8–0.9 μM in leukaemia cells (Yang et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2013). Paris saponin VI showed anticancer activity toward the liver cancer line with IC50 of 8.18 μM and 6.65 μM (Wang et al., 2019). Paris saponin VII inhibited the growth of human cervical cancer cells with an IC50 of 2.62 ± 0.11 μM (Zhang et al., 2014), liver cancer cells with an IC50 of 0.80–2.75 μM (Wang et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2019) and drug-resistant ovarian cancer cell lines (Yang et al., 2015a, Yang et al., 2015b). Similarly, paris saponin H inhibited the growth of liver cancer cells with an IC50 of 1.25 μM (Chen et al., 2019), diosgenin lung cancer cells with IC50 of 149.75 ± 10.43 μM (Yan et al., 2009), pennogenins liver cancer cells with IC50 of 9.7–13.5 μM (Zhu et al., 2011). Paris saponin I inhibited the growth of ovarian cancer cells with IC50 of <15 μM (Xiao et al., 2009), liver cancer cells with IC50 of 0.84–4.66 μM (Wang et al., 2019), gastric cancer cells with IC50 from 30.4 to 20.3 μM (Song et al., 2016) and lung cancer cells with IC50 from 1.21 to 2.51 μg/mL (Jiang et al., 2014a, 2014b; Liu et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2015). Likewise, paris saponin II inhibited the growth of lung cancer cells (Zhang et al., 2016a, Zhang et al., 2016b), liver cancer cells (Wang et al., 2019), and ovary cancer cells (Xiao et al., 2012, 2014; & Yang et al., 2015); polyphyllin I inhibited the growth of liver cancer cells (Xiao et al., 2018; Han et al., 2015), bone cancer cells (Chang et al., 2015) and lung cancer cells (Feng et al., 2019); polyphyllin VII inhibited the growth of lung cancer cells (Lin et al., 2015; He et al., 2020; Feng et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2015), liver cancer cells (Zhang et al., 2016a, Zhang et al., 2016b), nasopharyngeal cancer cells (Chen et al., 2016) and brain cancer cells (Pang et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020).

The data reveals that IC50 of saponins is comparable to that of synthetic chemotherapeutic drugs, and the same saponin type has anticancer action against multiple types of cancer. Because, drug resistance and clinical relapse are widespread in cancer treatment, the use of P. polyphylla streroidal saponins maybe a dependable source. Natural products inhibited the growth of human cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by triggering apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, with only minor harmful side effects on the host's normal tissues and cells (Hannun, 1997; Zhang et al., 2018). Excessive consumption of paris saponins resulted in nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and possibly heart palpitations and seizures (Liu et al., 2012). As a result, natural products extracted from P. polyphylla such as steroidal saponins and triterpenoid saponins have fewer negative effects in humans than synthetic drugs, and can thus be developed as natural drugs for cancer treatment. Because, the amount of steroidal saponin generated in vivo cannot meet the requirement, the approach for in vitro enhancement of these chemicals using tissue culture technology will be advantageous in future.

These compounds have also demonstrated suppression of carcinoma cell proliferation, cell autophagy and cell death occurs on the types of cancer cell lines and the compounds/drugs used via numerous routes based such as mitochondrial dysfunction (Lee et al., 2005; Cheung et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2009; AlSawah et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2014a, 2014b; Zhao et al., 2015; Song et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019), cell arrest at G2/M phase (Xiao et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2014a, 2014b; Zhao et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2015; Song et al., 2016), cell arrest at G1-phase (Chen et al., 2018), cell arrest at G2/S-phase (Wang et al., 2019), ROS-oxidative stress pathway (Wang et al., 2019), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways (Xiao et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2016), suppress pathological angiogenesis (Xiao et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015a, Yang et al., 2015b), suppress nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway (Yang et al., 2015a, Yang et al., 2015b; Han et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018; He et al., 2020), suppress vasculogenic mimicry (Xiao et al., 2018), suppress the CIP2A/AKT/mTOR pathway (Feng et al., 2019), suppress PI3K/Akt pathway (He et al., 2020) and suppress ROS induced AKT/mTORC1 activity (Pang et al., 2019).

4.2. Antioxidant activity

Antioxidants are chemicals that prevent proteins, lipids, DNA, and other molecules within cells from free radicals and oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is reported to result in ageing and diseases such as cancer, heart disease, cognitive decline and immune system decline. Water-soluble antioxidants, on the other hand, react with oxidants in the cell cytosol and blood plasma, whereas lipid-soluble antioxidants protect cell membranes from lipid peroxidation (Vertuani et al., 2004). Methanol, ethanol, petroleum ether, water extracts and steroidal saponins derived from the rhizome of P. polyphylla showed antioxidant activity (Mayirnao and Bhat, 2017; Devi et al., 2018; Lepcha et al., 2019). Ethanol extract of P. polyphylla had a strong antioxidant activity with an IC50 value of 68 μg/mL (Devi et al., 2018), but the methanol extract had a very weak antioxidant activity with an IC50 value of 1.09 mg/mL (Mayirnao and Bhat, 2017). Antioxidant activity of sample or extract is classified as strong if the IC50 value is 50–100 μg/mL, moderate if the IC50 value is 100–150 μg/mL, and weak if the IC50 is 151–200 μg/mL (Prakash and Okawa, 2001; Diantini et al., 2013).

4.3. Antimicrobial activity

Methanol, ethanol and water extracts from the leaves, rhizome and whole plant of P. polyphylla showed antifungal activity (Mayirnao and Bhat, 2017; Deng et al., 2008; Qin et al., 2018; Joshi et al., 2020) and antibacterial activity (Mayirnao and Bhat, 2017; Qin et al., 2018; Joshi et al., 2020). Similarly, pure compounds isolated from P. polyphylla also showed antifungal activities in vitro. Pennogenins showed antifungal activity with minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.6 mg/mL to 2.5 mg/mL (Zhu et al., 2011). Steroidal saponins showed antifungal effects on Candida albicans with the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of 5.15 and 10.3 μg/mL respectively (Qin et al., 2018). Pennogenin steroidal saponins showed 0.6–2.5 mg/mL MIC against Saccharomyces cerevisae, and 0.6–1.2 mg/mL MIC against Candida albicans (Zhu et al., 2011). It shows that pennogenin steroidal saponins were more effective against Candida albicans than others. The steroidal saponins were selective in their activity against different types of bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (100%), Staphylococcus aureus (80%), Listeria innocua (65%), Escherichia coli (57%), Salmonella enteric (67%), and Shigella sonnei (47%) (Mayirnao and Bhat, 2017; Qin et al., 2018; Joshi et al., 2020).

4.4. Antiviral activity

Methanol extracts from P. polyphylla leaves were found to be active against Chikungunya virus with an IC50 of 8.74 μg/mL (Joshi et al., 2020). Polyphylla saponin I derived from P. polyphylla was found to have antiviral action against the influenza A virus (Pu et al., 2015). On MDCK cells, polyphylla saponin I at 40 μg/mL inhibited 91.4% of influenza A virus infection, while oseltamivir (positive control) at the same dose inhibited 91.7% of influenza A virus infection (Pu et al., 2015).

4.5. Antileishmanian activity

Leishmaniasis is an intracellular protozoan parasitic disease caused by approximately twenty Leishmania species. It is spread through the bite of female phlebotomine sandflies of over 90 different species. Every year, between 700,000 and 1 million new cases of leishmania emerge (WHO, 2022). In vitro antileishmanial activity was found in steroidal saponins extracted from the rhizome of P. polyphylla (Devkota et al., 2007). Strong (IC50 = 0.23 μM), mild (IC50 = 0.93–36.87 μM), and moderate (IC50 = 1.59–83.72 μg/mL) antileishmanial activity were observed in chloroform, ethyl acetate and butanol extracts of the plant.

4.6. Anthelmintic activity

The anthelmintic activity evaluation of the methanol extract of P. polyphylla rhizome showed an EC50 value of 18.06 mg/L (Wang et al., 2010). Polyphyllin D (EC50 of 0.70 mg/L) and dioscin (EC50 of 0.44 mg/L) were extracted from crude methanol extract and showed greater anthelmintic activity than crude methanol extract (Wang et al., 2010).

4.7. Gynaecological disorder

One of the most prevalent illnesses in women is abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). AUB refers to abnormal uterine bleeding caused by structural issues, pregnancy difficulties (Ely et al., 2006) and contraception (Schrager, 2002). It could also be caused by benign and malignant tumours as well as pregnancy-related diseases and endocrine disorders. In vitro, steroidal saponins derived from the rhizome of P. polyphylla reduced abnormal uterine bleeding in rats by eliciting phasic myometrial contractions (Guo et al., 2018). Total steroidal saponins (TSSP) produced a response in the rat myometrium that was 23.19 ± 0.27% of the potassium response, and the EC50 value of TSSP was 19.82 ± 0.42 μg/mL. Under the same conditions, the highest potassium responses to oxytocin and PGF-2a (labor-inducing drugs) were 51.09 ± 0.03% and 42.00 ± 0.05%, respectively. It shows that TSSP has a stronger effect on rat myometrial contraction than oxytocin or PGF-2a.

4.8. Antityrosinase enzyme activity (Cosmetic value)

Copper-containing tyrosinase enzymes found inside melanosomes in plant and animal tissues catalyze the oxidation of tyrosine to produce melanin (black pigment) and other pigments. Tyrosinase inhibitors have shown to be effective in the treatment of melanin hyperpigmentation-related skin diseases or melanin-biosynthesis-related skin diseases. P. polyphylla rhizome extracts in chloroform, ethyl acetate and butanol demonstrated weak to moderate inhibition of the tyrosinase enzyme (Devkota et al., 2007). Similarly, przewalskinone B, isolated from the rhizome of P. polyphylla, had an IC50 of 0.25 mM against the tyrosinase enzyme (Devkota et al., 2007).

5. Conclusion

Due to the existence of useful secondary metabolites, it has been identified as a potential candidate for the treatment of several types of cancer and other disorders in modern medicine. The rhizome is the most extensively used plant part, and it has more activity against cancer cell lines, pathogens, and parasites as compared to above-ground parts. Based on in vitro and in vivo experiments, several pure steroidal saponins and crude extracts of P. polyphylla showed potent activity against carcinoma cell lines, bacteria, and parasites. As a result, it will be a promising plant for future studies of anticancer medications.

6. Future prospectives

Paris polyphylla is an endangered plant species that have been used as high-valued medicinal herb in traditional medicine. The natural population is decreasing due to over-exploitation and collection to meet the demand in traditional medicine. It is necessary to conserve its natural population through plant tissue culture technique and production of high-valued secondary metabolites in culture for sustainable utilization of such compounds in the production of pharmaceutical drugs.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Acharya R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants of resunga hill used by Magar community of badagaun VDC, gulmi district, Nepal. Sci. World. 2012;10(10):54–65. [Google Scholar]

- AlSawah E., Marchion D.C., Xiong Y., Ramirez I.J., Abbasi F., Boac B.M., Bush S.H., Bou Zgheib N., McClung E.C., Khulpateea B.R., Berry A., Hakam A., Wenham R.M., Lancaster J.M., Judson P. The Chinese herb polyphyllin D sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin-induced growth arrest. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015;141(2):237–242. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1797-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral S.R., Kurmi P.P. Mrs. Rachana Sharma; Kathmandu, Nepal: 2006. A Compendium of Medicinal Plants in Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai S., Chaudhary R.P., Taylor R.S.L. Ethnomedicinal plants used by the people of Manang district, Central Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006;2(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham J. Vol. 7. Chapman & Hall, 26 Boundary Row; London SEI 8HN, UK: 1994. Dictionary of Natural Products. (Executive editor) [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.Y.W., Koonb J.C.M., Liua X., Detmarc M., Yud B., Konge S.K., Funga K.P. Polyphyllin D, a steroidal saponin from Paris polyphylla, inhibits endothelial cell functions in vitro and angiogenesis in zebrafish embryos in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J., Wang H., Wang X., Zhao Y., Zhao D., Wang C., Li Y., Yang Z., Lu S., Zeng Q., Zimmerman J., Shi Q., Wang Y., Yang Y. Molecular mechanisms of Polyphyllin I-induced apoptosis and reversal of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human osteosarcoma cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan H.K. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020. 2020. Paris polyphylla. e.T175617476A176257430. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla H.S. third ed. Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Ltd.; New Delhi: 2014. Introduction to Biotechnology. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.X., Zhang Y.T., Zhou J. The glycosides of aerial parts of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Acta Bot. Yunnanica. 1995;17:473–478. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.X., Zhou J., Zhang Y.T., Zhao Y.Y. Steroid saponins of aerial parts of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Acta Bot. Yunnanica. 1990;12:323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.C., Hsieh M.J., Chen C.J., Lin J.T., Lo Y.S., Chuang Y.C., Chien S.Y., Chen M.K. Polyphyllin G induces apoptosis and autophagy in human nasopharyngeal cancer cells by modulation of AKT and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2016;7(43):70276–70289. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Ye K., Zhang B., Xin Q., Li P., Kong A-Ng., Wen X., Yang J. Paris Saponin II inhibits colorectal carcinogenesis by regulating mitochondrial fission and NF-κB pathway. Pharmacol. Res. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Lin J., Tang D., Zhang M., Wen F., Xue D., Zhang H. Paris saponin H suppresses human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by inactivation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019;12(8):2875–2886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J.Y.N., Onga R.C.Y., Suena Y.K., Ooib V., Wong H.N.C., Mak T.C.W., Funga K.P., Yue B., Konga S.K. Polyphyllin D is a potent apoptosis inducer in drug-resistant HepG2 cells. Cancer Lett. 2005;217:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission . Volume I. Medical Science Press; Beijing: 2015. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham A.B., Brinckmannc J.A., Bid g, Y.-F., Peib S.-J., Schippmanne U., Luof P. Paris in the spring: a review of the trade, conservation, and opportunities in the shift from wild harvest to cultivation of Paris polyphylla (Trilliaceae) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;222:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb C.R., Jamir S.L., Jamir N.S. Studies on vegetative and reproductive ecology of Paris polyphylla smith: a vulnerable medicinal plant. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2015;6:2561–2568. [Google Scholar]

- Deng D., Denis R.L., Janine M.C., Dwayne J.J., Kirstin V.W., Jenine E.U., Richard D.C., Wang M.Z., Zhang M. Antifungal saponins from Paris polyphylla Sm. Planta Med. 2008;74:1397–1402. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1081345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi W.J., Laishram J.M., Chakraborty S. Antioxidant activity and polyphenol contents of Paris polyphylla smith and prospects of in situ conservation. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2018;7(5):2355–2367. [Google Scholar]

- Devkota K.P., Khan M.T.H., Ranjit R., Lannang A.M., Samreen, Choudhary M.I. Tyrosinase inhibitory and antileishmanial constituents from the rhizomes of Paris polyphylla. Nat. Prod. Res. 2007;21(4):321–327. doi: 10.1080/14786410701192777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diantini A., Subarnas A., Lestari K., et al. Kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside isolated from the leaves of Schima wallichii Korth. inhibits MCF-7 breast cancer cell proliferation through activation of the caspase cascade pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2013;3(5):1069–1072. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.-G., Zhao Y.-L., Zhang J., Zuo Z.-T., Zhang Q.-Z., Wang Y.-Z. The traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological properties of Paris L. (Liliaceae): a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021;278:114293. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOA . Department of Ayurveda, Kathmandu, and the World Health Organization; 2003. Training Manual for Community People on Farming of Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- DPR . Department of Plant Resource, Thapathali; Kathmandu: 2017. Plant Source, Newsletter. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey R.C. S. Chand Publishing; New Delhi: 1993. A Text Book of Biotechnology. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta I.C. Hillside Press; Kathmandu: 2007. Non-Timber Forest Products Of Nepal: Identification, Classification, Ethnic Uses, and Cultivation. [Google Scholar]

- Ely J.W., Kennedy C.M., Clark E.C., Bowdler N.C. Abnormal uterine bleeding: a management algorithm. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2006;19:590–602. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Sánchez M.L., Sánchez-Sánchez L., Sandoval-Ramírez J. Licensee InTech; 2015. Steroidal Saponins and Cell Death in Cancer.http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 [Google Scholar]

- Feng F.F., Cheng P., Sun C., Wang H., Wang W. Inhibitory effects of polyphyllins I and VII on human cisplatin-resistant NSCLC via p53 upregulation and CIP2A/AKT/mTOR signaling axis inhibition. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2019;17(10):768–777. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(19)30093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Su J., Deng B.W., Yu Z.Y., Kang L.P., Zhao Z.H., Shan Y.J., Chen J.P., Ma B.P., Cong Y.W. Active pharmaceutical ingredients and mechanisms underlying phasic myometrial contractions stimulated with the saponin extract from Paris polyphylla Sm. var. yunnanensis used for abnormal uterine bleeding. Hum. Reprod. 2008;23(4):964–971. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Liu Z., Li K., Cao G., Sun C., Cheng G., Zhang D., Peng W., Liu J., Qi Y., Zhang L., Wang P., Chen Y., Lin Z., Guan Y., Zhang J., Wen J., Feng W., Wang F., Kong F., Xu D., Zhao S. Paris polyphylla-derived saponins inhibit growth of bladder cancer cells by inducing mutant P53 degradation while up-regulating CDKN1A expression. Curr. Urol. 2018;11:131–138. doi: 10.1159/000447207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W., Hou G., Liu L. Polyphyllin I (PPI) increased the sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells to chemotherapy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015;8(11):20664–20669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Xu C., Zheng L., Wang K., Jin M., Sun Y., Yue Z. Polyphyllin VII induces apoptotic cell death via inhibition of the PI3K/Akt and NF-κB pathways in A549 human lung cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020;21:597–606. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Zheng L., Sun Y.P., Zhang G.W., Yue Z.G. Steroidal saponins from Paris polyphylla suppress adhesion, migration, and invasion of human lung cancer A549 cells via down-regulating MMP-2 and MMP-9. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP. 2014;15(24):10911–10916. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.24.10911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R., Yu W., Zhuo Y., Yang Y., Hu X. Paris polyphylla extract inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis in A549 lung cancer cells. Trop. J. Pharmaceut. Res. 2017;16(9):2121–2126. [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.X., Gao W.Y., Man S.L., Zhao Z.Y. Advances in studies on saponins in plants of Paris L. and their biosynthetic approach. Tradit. Herb. Drugs. 2009;40:483–489. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN . IUCN–The World Conservation Union; Kathmandu, Nepal: 2004. National Register Of Medicinal And Aromatic Plants (Revised and Updated) [Google Scholar]

- Jamir N.S., Lanusunep, Pongener N. Medico-herbal medicine practiced by the naga tribes in the state of Nagaland (India) Ind. J. Fund. Appl. Life Sci. 2012;2:328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Fritsch P.W., Li H., Xiao T., Zhou Z. Vol. 98. 2006. Anals of Botany; pp. 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Zhao P.-J., Su D., Feng J., Ma S. Paris saponin I induces apoptosis via increasing the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3 expression in gefitinib-resistant non-small cell lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014;9:2265–2272. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Zhao P., Feng J., Su D., Ma S. Effect of Paris saponin I on radiosensitivity in a gefitinib-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Oncol. Lett. 2014;7:2059–2064. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi B., Panda S.K., Jouneghani R.S., Liu M., Parajuli N., Leyssen P., Neyts J., Luyten W. Antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and anthelmintic activities of medicinal plants of Nepal selected based on ethnobotanical evidence. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2020/1043471. Article ID 1043471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- K.C. M., Phoboo S., Jha P.K. Ecological study of paris polyphylla Sm. ECOPRINT. 2010;17:87–93. www.nepjol.info/index.php/eco www.ecosnepal.com Ecological Society (ECOS), Nepal, [Google Scholar]

- Kang L.P., Liu Y.X., Eichhorn T., Dapat E., Yu H.S., Zhao Y., Xiong C.Q., Liu C., Efferth T., Ma B.P. Polyhydroxylated steroidal glycosides from Paris polyphylla. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:1201–1205. doi: 10.1021/np300045g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunwar R.M., Nepal B.K., Kshhetri H.B., Rai S.K., Bussmann R.W. Ethnomedicine in himalaya: a case study from dolpa, humla, jumla, and mustang districts of Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-27. http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/2/1/27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunwar R.M., Adhikari Y.P., Sharma H.P., Rimal B., Devkota H.P., Charmakar S., Acharya R.P., Baral K., Ansari A.S., Bhattarai R., Thapa S., Paudel H.R., Baral S., Sapkota P., Uprety Y., LeBoa C., Jentsch A. Nepal. Global Ecology and Conservation. 2020. Distribution, use, trade, and conservation of Paris polyphylla Sm. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane D., Baral D., Nepali K.M. Documentation of medicinal plants conserved in national botanical garden. Godawari Lalitpur. Bul. Dept. Pl. Res. 2014;36:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.S., Yuet-Wa J.C., Kong S.K., Yu B., Eng-Choon V.O., Nai-Ching H.W., Chung-Wai1 T.M., Fung K.P. Effects of polyphyllin D, a steroidal saponin in Paris polyphylla, in growth inhibition of human breast cancer cells and xenograft. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005;4(11):1248–1254. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.11.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepcha D.L., Chhetri A., Chhetri D.R. Antioxidant and cytotoxic attributes of Paris polyphylla smith from Sikkim himalaya. J. Pharmacogn. 2019;11(4):705–711. [Google Scholar]

- Li F.R., Jiao P., Yao S.T., Sang H., Qin S.C., Zhang W., Zhang Y.B., Gao L.L. Paris polyphylla Sm. Extract induces apoptosis and activates cancer suppressor gene Connexin26 expression. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP. 2012;13:205–209. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Gu J.F., Zou X., Wu J., Zhang M.H., Jiang J., Qin D., Zhou J.Y., Liu B.X.Z., Zhu Y.T., Jia X.B., Feng L., Wang R.P. The anti-lung cancer activities of steroidal saponins of P. polyphylla smith var. chinensis (franch.) hara through enhanced immunostimulation in experimental lewis tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice and induction of apoptosis in the A549 cell line. Molecules. 2013;18:12916–12936. doi: 10.3390/molecules181012916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S.Y. Science Press; St. Louis: 2000. Flora of China. Beijing, and Missouri Botanic Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Liu Y., Li F., Wu J., Zhang G., Wang Y., Lu L., Liu Z. Anti-lung cancer effects of polyphyllin VI and VII potentially correlate with apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Phytother Res. 2015;29:1568–1576. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Gao W., Man S., Wang J., Li N., Yin S., Wu S., Liu C. Pharmacological evaluation of sedative-hypnotic activity and gastro-intestinal toxicity of Rhizoma Paridis saponins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;144:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Chai Y., Hu L., Wang J., Pan X., Yuan H., Zhao Z., Song Y., Zhang Y. Polyphyllin VI induces apoptosis and autophagy via reactive oxygen species mediated JNK and P38 activation in glioma. OncoTargets Ther. 2020;13:2275–2288. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S243953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Zheng Q., Chen W., Yuou S., Yuou M., Teng Y., Meng X., Zhang Y., Yu P., Gao W. Paris saponin I inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis through down-regulating AKT activity in human non-small-cell lung cancer cells and inhibiting ERK expression in human small-cell lung cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2016;6:70816–70824. [Google Scholar]

- Long C.L., Li H., Ouyang Z., Yang X., Li Q., Trangmar B. Strategies for agrobiodiversity conservation and promotion: a case from Yunnan, China. Biodivers. Conserv. 2003;12:1145–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Luitel D.R., Pathak M. Jour. Dept. Pl. Res.; 2013. Documentation of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, Western Nepal. No. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Manandhar N.P. Second Avenue. Timber Press, Inc.; U.S.A: 2002. Plants and People of Nepal. (The Haseltine Building 133 S.W). Suite 450 Portland, Oregon 97204. [Google Scholar]

- Mayirnao H.S., Bhat A.A. Evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Paris polyphylla Sm. Asian J. Pharmaceut. Clin. Res. 2017;10(11):315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Negi J.S., Bisht V.K., Bhandari A.K., Bhatt V.P., Singh P., Singh N. Paris polyphylla: chemical & biological prospectives. Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2014;14(6):833–839. doi: 10.2174/1871520614666140611101040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang D., Li C., Yang C., Zou Y., Feng B., Li L., Liu W., Geng Y., Luo Q., Chen Z., Huang C. Polyphyllin VII promotes apoptosis and autophagic cell death via ROS-inhibited AKT activity and sensitizes glioma cells to temozolomide. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019;19 doi: 10.1155/2019/1805635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant B. In: Infectious Diseases and Nanomedicine II. Adhikari R., Thapa S., editors. Vol. 808. 2014. Application of plant cell and tissue culture for the production of phytochemicals in medicinal plants; pp. 25–39. (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A., Gajurel P.R., Das A.K. Threats and conservation of Paris polyphylla an endangered, highly exploited medicinal plant in the Indian Himalayan Region. Biodiversitas. 2015;16:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash A., Okawa Antioxidant activity. Medallion Lab. Anal. Prog. 2001;19(2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pu X., Ren J., Ma X., Liu L., Yu S., Li X., Li H. Polyphylla saponin I has antiviral activity against the influenza A virus. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015;8(10):18963–18971. www.ijcem.com/ISSN:1940-5901/IJCEM0013014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X.-J., Ni W., Chen C.-X., Liu H.-Y. Seeing the light: shifting from wild rhizomes to extraction of active ingredients from above-ground parts of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajbhandari K.R. Ethnobotanical Society of Nepal (ESON); 2001. Ethnobotany of Nepal; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Ramawat K.G., Goyal S. S. Chand Publishing; India: 2004. Comprehensive Biotechnology. [Google Scholar]

- Ruamrungsri N., Siengdee P., Sringarm K., Chomdej S., Ongchai S., Nganvongpanit K. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.—Animal. 2016. In vitro cytotoxic screening of 31 crude extracts of Thai herbs on a chondrosarcoma cell line and primary chondrocytes and apoptotic effects of selected extracts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrager S. Abnormal uterine bleeding associated with hormonal contraception. Am. Fam. Physician. 2002;65:2073–2080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S.A., Mazumder P.B., Choudhury M.D. Medicinal properties of Paris polyphylla smith: a review. J. Herbal Med. Toxicol. 2012;6(1):27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M., Garrett W.S., Chan A.T. Nutrients, foods, and colorectal cancer prevention. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1244–1260. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Du L., Jiang H., Xhu X., Li J., Xu J. Paris saponin I sensitizes gastric cancer cell lines to cisplatin via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Med. Sci. Mon. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2016;22:3798–3803. doi: 10.12659/MSM.898232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparg S.G., Light M.E., Staden J.V. Biological activities and distribution of plant saponins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004;9:219–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Liu B.R., Hu W.J., Yu L.X., Qian X.P. In vitro anticancer activity of aqueous extracts and ethanol extracts of fifteen traditional Chinese medicines on human digestive tumor cell lines. Phytother Res. 2007;21(11):1102–1104. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G.-E., Niu Y.-X., Li Y., Wu C.-Y., Wang X.-Y., Zhang J. Paris saponin VII enhanced the sensitivity of HepG2/ADR cells to ADR via modulation of PI3K/AKT/MAPK signaling pathway. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2019;36:98–106. doi: 10.1002/kjm2.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertuani S., Angusti A., Manfredini S. The antioxidants and pro-antioxidants network: an overview. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2004;10(14):1677–1694. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384655. PMID:15134565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Liu Y., Sun M., Sai N., You L., Dong X., Yin X., Ni J. Hepatocellular toxicity of paris saponins I, II, VI, and VII on two kinds of hepatocytes-HL-7702 and HepaRG cells, and the underlying mechanisms. Cells. 2019;8(690):1–18. doi: 10.3390/cells8070690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Gao W., Liu X., Zuo Y., Chen H., Duan H. Anti-tumor constituents from Paris polyphylla. Asian J. Trad. Med. 2005;11 [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.X., Han J., Zhao L.W., Jiang D.X., Liu Y.T., Liu X.L. Anthelmintic activity of steroidal saponins from Paris polyphylla. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:1102–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WCSP . 2020. World Checklist of Selected Plant Families Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens.http://wcsp.science.kew.org/Retrievedon3/5/2020 Kew. Published on the Internet: [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Wang L., Guo-Cai W., Hui W., Yi D., Wen-Cai Y., Yao-Lan L. New steroidal saponins and sterol glycosides from Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Planta Med. 2012;78:1667–1675. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Wang L., Wang G.-C., Wang H., Dai Y., Yang X.-X., Ye W.-C., Li Y.-L. Carbohydrate Research; 2012. Triterpenoid Saponins from Rhizomes of Paris Polyphylla Var. Yunnanensis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Li Q., Liu Y. Polyphyllin D induces apoptosis in K562/A02 cells through G2/M phase arrest. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013;66:713–721. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Leishmaniasis. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Zou J., Bui-Nguyen T.M., Bai P., Gao L., Liu J., Liu S., Xiao J., Chen X., Zhang X., Wang H. Paris saponin II of Rhizoma Paridis – a novel inducer of apoptosis in human ovarian cancer cells. BioSci. Trends. 2012;6(4):201–211. doi: 10.5582/bst.2012.v6.4.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Yang M., Xiao J., Zou, Huang J.Q., Yang K., Zhang B., Yang F., Liu S., Wang H., Bai P. Paris Saponin II suppresses the growth of human ovarian cancer xenografts via modulating VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and tumor cell migration. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014;73:807–818. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Bai P., Nguyen T.M.B., Xiao J., Liu S., Yang G., Hu L., Chen X., Zhang X., Liu J., Wang H. The antitumoral effect of Paris Saponin I associated with the induction of apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. Mol. Cancer Therapeut. 2009;8(5):1179–1188. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T., Zhong W., Zhao J., Qian B., Liu H., Chen S., Qiao K., Lei Y., Zong S., Wang H., Liang Y., Zhang H., Meng J., Zhou H., Sun T., Liu Y., Yang C. Polyphyllin I suppresses the formation of vasculogenic mimicry via Twist1/VEcadherin pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:906. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0902-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L.L., Zhang Y.J., Gao W.Y., Man S.L., Wang Y. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of steroid saponins of Paris polyphylla var . yunnanensis. Exp Oncol. 2009;31(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Zou J., Zhu H., Liu S., Wang H., Bai P., Xiao X. Paris saponin II inhibits human ovarian cancer cell-induced angiogenesis by modulating NF-κB signaling. Oncol. Rep. 2015;33:2190–2198. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R., Qi J., Zhang J., Wang F., Fan L. In vitro effects of saponin VII and silica nanocomposite on ovarian cancer drug resistance of ovarian cancer. Chinese Med J. 2015;95(23):1859–1861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Cai H., Meng X. Polyphyllin D induces apoptosis and differentiation in K562 human leukemia cells. Int. Immunopharm. 2016;36:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q., Li Q., Lu P., Chen Q. Polyphyllin D induces apoptosis in U87 human glioma cells through the c-jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway. J. Med. Food. 2014;17(9):1036–1042. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Li K., Sun C., Cao G., Qi Y., Lin Z., Guo Y., Liu Z., Chen Y., Liu J., Cheng G., Wang P., Zhang L., Zhang J. Anti-cancer effects of paris polyphylla ethanol extract by inducing cancer cell apoptosis and cycle arrest in prostate cancer cells. Curr. Urol. 2018;11:144–150. doi: 10.1159/000447209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.Y., Wang Y.Z., Zhao Y.L., Yang S.B., Zuo Z.T., Yang M.Q., Zhang J., Yang W.Z., Yang T.M., Jin H. Phytochemicals and bioactivities of Paris species. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2011;13(7):670–681. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Zhang D., Ma X., Liu Z., Li F., Wu D. Paris saponin VII suppressed the growth of human cervical cancer Hela cells. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2014;19:41. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-19-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Jia X., Bao J., Chen S., Wang K., Zhang Y., Li P., Wan J.B., Su H., Wang Y., Mei Z., He C. Polyphyllin VII induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells through ROS-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and MAPK pathways. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2016;16:58. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1036-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Man S., Wang Y., Liu J., Liu Z., Yu P., Gao W. Paris Saponin II induced apoptosis via activation of autophagy in human lung cancer cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Shi Q. Analysis on the therapeutic effect on colporrhagia due to drug abortion (240 cases) treated by Gongxuening. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2005;21:455–456. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P., Jiang H., Su D., Feng J., Ma S., Zhu X. Inhibition of cell proliferation by mild hyperthermia at 43˚C with Paris Saponin I in the lung adenocarcinoma cell line PC-9. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;11:327–332. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Yang C.Z. Heptasaccharide and octasaccharide isolated from Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis and their plant growth-regulatory activity. Plant Sci. 2003;165:571–575. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Tan J., Wang B., Guan L., Liu Y., Zheng C. In-vitro antitumor activity and antifungal activity of pennogenin steroidal saponins from Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. (IJPR) 2011;10(2):270–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.