Abstract

Germination of radish (Raphanus sativus cv Eterna) seeds can be inhibited by far-red light (high-irradiance reaction of phytochrome) or abscisic acid (ABA). Gibberellic acid (GA3) restores full germination under far-red light. This experimental system was used to investigate the release of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) by seed coats and embryos during germination, utilizing the apoplastic oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin to fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein as an in vivo assay. Germination in darkness is accompanied by a steep rise in ROI release originating from the seed coat (living aleurone layer) as well as the embryo. At the same time as the inhibition of germination, far-red light and ABA inhibit ROI release in both seed parts and GA3 reverses this inhibition when initiating germination under far-red light. During the later stage of germination the seed coat also releases peroxidase with a time course affected by far-red light, ABA, and GA3. The participation of superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals in ROI metabolism was demonstrated with specific in vivo assays. ROI production by germinating seeds represents an active, developmentally controlled physiological function, presumably for protecting the emerging seedling against attack by pathogens.

Reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) comprise superoxide radicals (O·2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH) formally originating from one-, two-, or three-electron transfers to dioxygen (O2). These incompletely reduced oxygen species are primarily known as toxic byproducts of various cellular O2-consuming redox processes such as photosynthetic or respiratory electron transport, which are responsible for causing symptoms of oxidative damage if ROI production exceeds the capacity of ROI-scavenging reactions. The toxicity of ROI strongly depends on the presence of a Fenton catalyst such as iron ions or peroxidase, giving rise to extremely reactive ·OH radicals in the presence of H2O2 and O·2− (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1989; Chen and Schopfer, 1999). In recent years it has emerged that the joint exudation of ROI and peroxidase plays an important role in the defense system of plants against pathogenic organisms (Vera-Estrella et al., 1993; Scott-Craig et al., 1995; Bestwick et al., 1998). Elicitor-mediated signals generated during the early phase of pathogen attack can induce rapid production of ROI by plant cells (“oxidative burst”; Baker and Orlandi, 1995; Lamb and Dixon, 1997; Wojtaszek, 1997), closely resembling the pathogen-activated ROI production by the inducible NADPH oxidase redox system in the plasma membrane of mammalian phagocytes (Henderson and Chappell, 1996). There is increasing evidence suggesting that O·2− and/or H2O2 can serve as integrating elements in the signaling circuitry controlling pathogen resistance responses, acquired immunity, and programmed cell death in plants (Jabs, 1999; Grant and Loake, 2000). It has recently been shown that roots of intact plants are capable of releasing H2O2 into the surrounding medium, even in the absence of pathogen attack or other stress elicitors (Frahry and Schopfer, 1998a).

Whereas the enzymatic mechanism involved in the inducible ROI production by phagocytic leukocytes is well known (Henderson and Chappell, 1996), the functionally corresponding enzyme system in plants has not yet been elucidated (Bolwell and Wojtaszek, 1997). Besides an hypothetical NAD(P)H oxidase related to the leukocyte enzyme (Doke et al., 1996; Tenhaken and Rübel, 1998; Kawasaki et al., 1999; Frahry and Schopfer, 2000), there are several other ROI-producing oxidases localized at the plasma membrane or in the wall of plant cells such as peroxidases, amine oxidases, and oxalate oxidase that are potential sources for apoplastic H2O2 (Bolwell and Wojtaszek, 1997). Intracellular H2O2-producing reactions located in chloroplasts, mitochondria, and peroxisomes could possibly contribute to ROI release since H2O2 easily permeates through cell membranes (Bass et al., 1983; Allan and Fluhr, 1997; del Río et al., 1998).

In recent years there has been a growing interest in the functional significance of ROI in seed aging, seed germination, and early seedling development. Most previous investigations with seeds or seedlings were concerned with the destructive effects of ROI such as lipid peroxidation during oxidative stress (Hendry, 1993; Leprince et al., 1995; Reuzeau and Cavalie, 1995). Much less attention has been paid to those physiological conditions where ROI are actively produced for serving a useful function within the seed or in its interaction with the environment. There are a few reports from work with soybean suggesting that seed germination is accompanied by a generation of ROI in the embryo axis as well as in the seed coat, which can be measured with suitable indicator reactions in situ or in the surrounding medium (Boveris et al., 1984; Puntarulo et al., 1988; 1991; Simontacchi et al., 1993; Gidrol et al., 1994; Khan et al., 1996). As seed germination represents a developmental period most sensitive for pathogen infection, it is conceivable that ROI release in this stage plays an important role in protecting the emerging embryo against invasion by parasitic organisms. With this idea in mind we have studied the release of ROI and peroxidase during seed germination in radish (Raphanus sativus cv Eterna). This species has the advantage that cultivars are available in which germination can be experimentally controlled by light and hormones. Using these tools for the experimental manipulation of germination, we determined the time courses of ROI release by embryos and seed coats. As peroxidase may be involved in the transformation of H2O2 into the much more toxic ·OH radical (Chen and Schopfer, 1999), we were also interested in the question of whether ROI release is accompanied by a release of this enzyme.

A second aim of this study was to identify the individual ROI species produced by germinating seeds. The separate estimation of H2O2, O·2−, and ·OH in a physiological reaction is difficult and has so far not been reported. The specific determination of H2O2 is relatively simple and can be achieved, for instance, with the fluorometric scopoletin oxidation assay (Andreae, 1955; Frahry and Schopfer, 1998a). After testing various procedures described in the literature we found that a photometric assay based on the reduction of newly introduced tetrazolium compounds (Na,3′-[1-[(phenylamino)-carbonyl]-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro)benzenesulfonic- acid hydrate [XTT]; and Na,2-[4-iodophenyl]-3-[4-nitrophenyl]-5-[2,4-disulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium [WST-1]) was suitable for the determination of O·2− in vivo (Sutherland and Learmonth, 1997; Berridge and Tan, 1998). It turned out that the degradation of deoxy-Rib or the hydroxylation of benzoate to fluorescent products could be used as indicator reactions for the determination of ·OH (Gutteridge, 1987; Halliwell et al., 1988).

RESULTS

Effect of Far-Red Light, Abscisic Acid (ABA), and Gibberellic Acid (GA3) on Germination

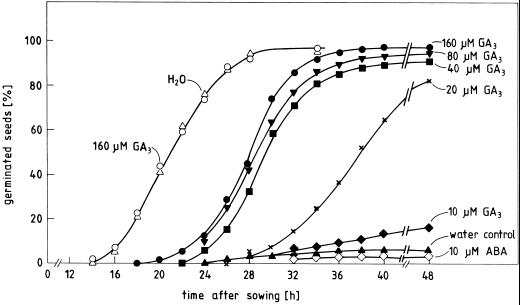

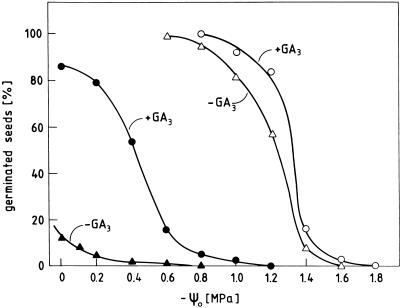

Background information on the germination behavior of the seed material used in the following experiments is given in Figures 1 and 2. The seeds of radish cv Eterna germinate in darkness at 25°C by 95% within 30 h after sowing. Continuous irradiation with far-red light (high irradiance reaction of phytochrome) or treatment with ABA in darkness prevent germination almost completely for more than 4 d. We have previously shown that light or ABA inhibit germination in such seeds by lowering the expansive force exerted by the embryo on the seed coat to a level below the critical level that must be exceeded for rupturing this constraining structure (Schopfer and Plachy, 1985, 1993). Figure 1 shows that the light inhibition of germination can be reversed by GA3 in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas the hormone has no effect on germination in darkness. Tetcyclacis (100 μm), an inhibitor of gibberellin biosynthesis, blocks germination in darkness and this inhibition can be reversed by GA3 (data not shown). The promotion of germination by GA3 in far-red light is accompanied by a strong increase in the ability to germinate under osmotic stress and can therefore be attributed to an increase in the expansive force that allows the embryo to overcome the mechanical seed coat restraint even in far-red light (Fig. 2). These data are in agreement with the interpretation that endogenous gibberellin formation is necessary for embryo expansion, and thus germination, and that far-red light affects germination by interfering with gibberellin synthesis in the embryo (Inoue, 1991; Bewley and Black, 1994; Sánchez and de Miguel, 1997).

Figure 1.

Time course of germination of radish seeds kept in darkness (white symbols) or continuous far-red light (black symbols) on water (H2O) or solutions containing GA3 (10–160 μm) or ABA (10 μm) from the time of sowing. GA3 had no effect on dark germination at any of the concentrations tested; therefore, only the data for the highest concentration are shown.

Figure 2.

Effect of osmotic constraint on the germination of radish seeds kept in darkness (white symbols) or continuous far-red light (black symbols) in the absence or presence of 160 μm GA3 on osmotic test solutions adjusted to negative water potentials (-ψ0) indicated on the abscissa. Final germination percentages were determined 72 h after sowing.

Release of ROI during Germination

The oxidative burst can be very sensitively demonstrated with the ROI probe, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin (DCFH) that is oxidized by H2O2 to highly fluorescent 2′,7′dichlorofluorescein (DCF) in a peroxidase-dependent reaction (Keston and Brandt, 1965). Although DCFH does not penetrate the plasma membrane, it can be introduced into the cell in the form of non-polar, unreactive DCFH-diacetate that is subsequently deacetylated by endogenous esterase. The polar, reactive DCFH liberated intracellularly, as well as the DCF produced in the reaction with ROI, remain trapped in the cytoplasm (Bass et al., 1983). The reaction can be inhibited by catalase and ·OH scavengers, indicating that H2O2 and ·OH can participate in the oxidation of DCFH (Bass et al., 1983; Cathcart et al., 1983; Scott et al., 1988; Simontacchi et al., 1993). We have adapted this procedure for the in vivo measurement of extraprotoplasmic ROI by preparing the substrate DCFH from DCFH-diacetate with esterase in the reaction mixture before adding the plant material to be analyzed. In this way ROI-dependent formation of the fluorochrome could be confined to the external space and quantitatively measured in the incubation medium.

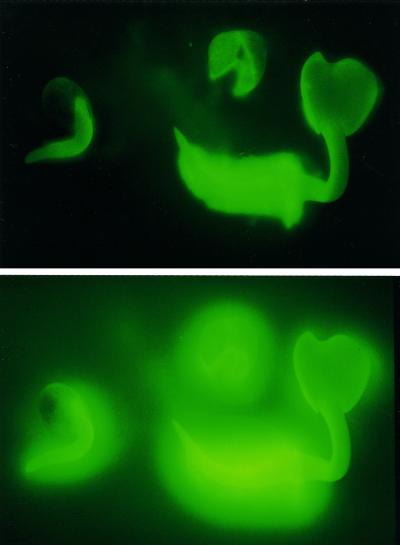

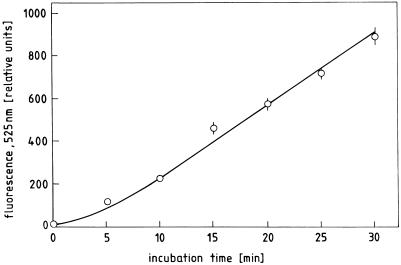

Embryos and coats of germinating radish seeds produce a rapid increase in fluorescence in the surrounding incubation medium containing DCFH and solidified with agar (Fig. 3). The reaction can be observed after less than 2 min in the root hair region of the radicle of young seedlings after liberation from the seed coat. A somewhat longer incubation time is needed to demonstrate a similar reaction in the seedling shoot, in the isolated seed coat, or in less advanced stages of germination. The ROI release can be quantitatively determined by measuring the increase in DCF fluorescence in a liquid incubation medium (Fig. 4). As the linearity of the reaction holds for at least 30 min, an end-point determination after an incubation period of 15 min could conveniently be used in the standard assay for measuring ROI release in the following experiments.

Figure 3.

Demonstration of ROI release by germinating seeds and young seedlings of radish. The yellow-green fluorescence indicates the conversion of DCFH into DCF in the surrounding of ROI-producing tissues. The pictures show a young seedling, an empty seed coat, and a germinating seed with protruding radicle 2 (top) or 30 (bottom) min after embedding in DCFH-containing agar medium. From a seed population germinated for 48 h in darkness.

Figure 4.

Time course of DCFH oxidation by radish seed coats. Three coats from 48-h dark-germinated seeds were incubated in 1.5 mL of DCFH assay medium in darkness.

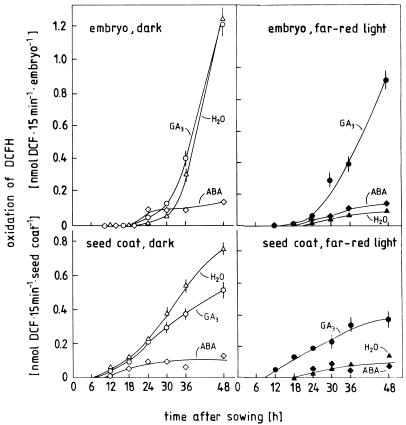

Germination of radish seeds under the experimental conditions shown in Figure 1 is accompanied by the release of ROI originating from the embryo as well as from the seed coat. The data shown in Figure 5 can be summarized as follows: ROI release can be detected in the seed coat already 6 to 12 h after sowing, i.e. 6 h before the onset of visible germination in the seed population. In contrast, the embryo acquires the ability to produce ROI only about 12 h later, i.e. after the onset radicle growth. There is a steep rise in ROI release in the coat and embryo of seeds germinating in darkness. Far-red light and ABA inhibit this rise almost completely in both seed parts; and GA3 reverses the inhibitory effect of far-red light in both seed parts, but has little effect during germination in darkness. This set of data shows that seed coat and embryo are capable of a “burst” of ROI production, whereby the seed coat covers the early phase and the embryo the later phase of the germination process. In both seed parts the effects of far-red light, ABA, and GA3 on ROI release are temporally correlated with the effects of these factors on germination.

Figure 5.

Time course of ROI release by embryos and coats of radish seeds kept in darkness (left) or continuous far-red light (right) on water (H2O) or solutions containing GA3 (160 μm) or ABA (10 μm) from the time of sowing. Embryos and seed coats were separated immediately before the assay.

Release of Peroxidase during Germination

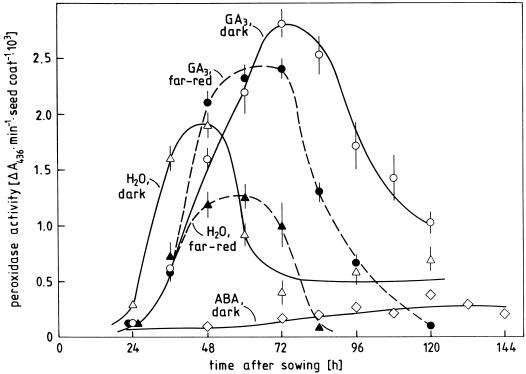

The coats of radish seeds secrete peroxidase during the later stage of germination and the initial seedling development. Time courses indicating the rate of peroxidase release by isolated seed coats incubated under the experimental conditions of Figure 1 are shown in Figure 6. These data can be summarized as follows: Peroxidase release starts between 24 and 36 h after sowing and reaches a maximal rate 24 to 48 h later, i.e. after the young plant has slipped out of the coat and has entered the seedling stage; peroxidase release by isolated seed coats can be almost completely prevented by ABA, but only partly inhibited by far-red light; and application of GA3 promotes peroxidase release in far-red light as well as in darkness. Moreover, GA3 shifts the period of maximal release on the time axis. This effect is most pronounced in darkness. Thus, although peroxidase release is promoted by conditions promoting germination, it is only loosely correlated with ROI production.

Figure 6.

Time course of peroxidase release by coats of radish seeds kept in darkness (white symbols) or continuous far-red light (black symbols) on water (H2O) or solutions containing GA3 (160 μm) or ABA (10 μm) from the time of sowing. Coats were isolated from the seeds after 24 h and further kept under the respective conditions. Activity of secreted peroxidase was determined in 2 mL of buffer in which seed coats had been incubated for 20 min.

Identification of O·2−, H2O2, and ·OH as ROI Produced during Germination

The activated NADPH oxidase system in the plasma membrane of leukocytes reduces O2 to O·2−, which can subsequently dismutate to H2O2 + O2 spontaneously or in a reaction catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (Henderson and Chappell, 1996). In addition, ·OH can be generated under these condition if Fe ions or peroxidase catalyze the further reduction of H2O2 to ·OH utilizing O·2− as an electron donor (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1989; Chen and Schopfer, 1999). If the “oxidative burst” of germinating radish seeds involves a similar sequence of reactions, it should be possible to identify O·2−, H2O2, and ·OH in the incubation medium. Table I shows that the DCFH oxidation by seed coats can be inhibited by a general antioxidant (ascorbate) as well as by scavengers of O·2− (superoxide dismutase), H2O2 (catalase), and ·OH (benzoate, adenine, mannitol, formate, and thiourea), but not by urea that demonstrates no scavenger activity (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1989). These data suggest that O·2−, H2O2, as well as ·OH are involved in ROI production in this material.

Table I.

Effect of ROI scavengers on ROI release by radish seed coats

| Inhibitor | ROI Release |

|---|---|

| % | |

| None | 100 ± 2 |

| Catalase (100 μg mL−1) | 53 ± 3 |

| Superoxide dismutase (100 μg mL−1) | 57 ± 2 |

| Na-ascorbate (10 mm) | 43 ± 2 |

| Na-benzoate (10 mm) | 55 ± 3 |

| Adenine (5 mm) | 53 ± 4 |

| Mannitol (10 mm) | 43 ± 3 |

| Na-formate (10 mm) | 47 ± 4 |

| Thiourea (10 mm) | 34 ± 2 |

| Urea (100 mm) | 95 ± 3 |

The ROI-dependent oxidation of DCFH by three coats from 48-h germinated seeds during a 15-min incubation period was determined in the presence of various inhibitors. The seed coats were preincubated in the inhibitor solution for 15 min before the addition of DCFH. Urea served as a negative control.

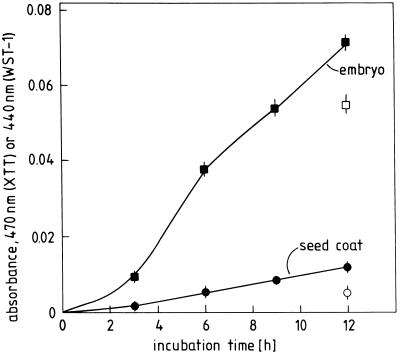

For identifying O·2−, H2O2, and ·OH in the “oxidative burst” of germinating radish seeds we employed assay reactions that are specific for one of these ROI. First, the production of O·2− by embryos and seed coats was demonstrated using the reduction of the tetrazolium salts XTT or WST-1 as indicator reactions (Fig. 7). Inhibitor data documenting the specificity of the assay and characterizing the underlying O·2−-generating reaction are compiled in Table II. The O·2− production by seed coats could be inhibited by superoxide dismutase and its low molecular weight mimic Mn-desferal (Rabinowitch et al., 1987; Able et al., 1998). The difference in effectiveness between these two O·2−-eliminating agents may be due to the restricted permeability of the enzyme through the cell wall (Able et al., 1998). Of diagnostic significance is the finding that O·2− production could be inhibited by DPI, an inhibitor of the leukocyte NADPH oxidase (Henderson and Chappell, 1996), but not by the peroxidase inhibitors KCN and NaN3. It should be noted in this context that inhibition by DPI alone can provide no unequivocal evidence for the involvement of the oxidase since DPI inactivates also hemoproteins such as peroxidase (Frahry and Schopfer, 1998b). Catalase as well as ·OH-scavenging substances such as mannitol or formate had no significant inhibitory effect on O·2− formation by seed coats. Qualitatively similar results were obtained in corresponding experiments with embryos, although the effectiveness of inhibitors was generally lower than in seed coats (data not shown). Taken together, these data show that seed coats and embryos do produce O·2− during germination. Moreover, differential sensitivity to diagnostic inhibitors indicates that a cyanide-resistant enzyme, functionally resembling the leukocyte NADPH oxidase, rather than a peroxidase-type enzyme, is responsible for this performance (Frahry and Schopfer, 2000).

Figure 7.

Time course of O·2− release by embryos and coats of germinating radish seeds. Ten embryos or 20 coats from 48-h dark-germinated seeds were incubated in 1 mL of XTT (black symbols) or WST-1 (white symbols) assay medium in darkness. Both reagents provided similar results after 12 h of incubation. XTT was selected for elaborating detailed time courses of O·2− formation. Data are normalized on a per embryo/seed coat basis.

Table II.

Effect of ROI scavengers and related inhibitors on O·2− release by radish seed coats

| Inhibitor | O·2− Release |

|---|---|

| % | |

| None | 100 ± 5 |

| Superoxide dismutase (100 μg mL−1) | 59 ± 8 |

| Mn-desferal (300 μm) | 0 ± 0 |

| Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) (100 μm)a | 48 ± 14 |

| KCN (1 mm) | 97 ± 14 |

| NaN3 (1 mm) | 89 ± 7 |

| Catalase (100 μg mL−1) | 82 ± 21 |

| Na-benzoate (10 mm) | 82 ± 21 |

| Adenine (5 mm) | 123 ± 15 |

| Mannitol (10 mm) | 81 ± 14 |

| Na-formate (10 mm) | 153 ± 24 |

| Thiourea (10 mm) | 91 ± 20 |

| Urea (100 mm) | 115 ± 14 |

The O·2−-dependent reduction of XTT by 20 coats from 48-h germinated seeds during a 3-h incubation period was determined in the presence of various inhibitors.

Including 10 μL mL−1 dimethylsulfoxide (ineffective in controls).

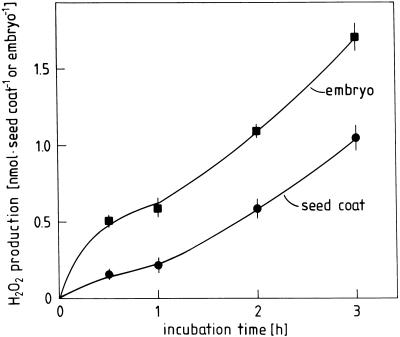

O·2− rapidly dismutates to O2 and H2O2, a relatively stable ROI generally representing the dominant product of “oxidative burst” reactions in plants and animals. H2O2 can be specifically determined by the peroxidase-dependent oxidation of phenolic substances such as scopoletin. Using this sensitive fluorometric assay, Figure 8 shows the time course of H2O2 production by radish seed coats and embryos after 48 h of germination in darkness. The reaction could be inhibited by H2O2 scavengers (catalase and KI), ascorbate, and DPI, but not by ·OH scavengers (mannitol and formate) and agents catalyzing the dismutation of O·2− (superoxide dismutase and Mn-desferal; Table III). Again, qualitatively similar results were obtained with embryos (data not shown). The results confirm the supposition that H2O2 is involved in the “oxidative burst” accompanying the germination of radish seeds. Inhibitor evidence is consistent with the concept that the H2O2 originates from the dismutation of apoplastic O·2−.

Figure 8.

Time course of H2O2 release by embryos and coats of germinating radish seeds. Five embryos or 10 coats from 48-h dark-germinated seeds were incubated in 3 mL of scopoletin assay medium in darkness.

Table III.

Effect of ROI scavengers and related inhibitors on H2O2 release by radish seed coats

| Inhibitor | H2O2 Release |

|---|---|

| % | |

| None | 100 ± 3 |

| Catalase (100 μg mL−1) | 72 ± 5 |

| KI (10 mm) | 47 ± 10 |

| Na-ascorbate (10 mm) | 63 ± 6 |

| DPI (100 μm)a | 42 ± 4 |

| Superoxide dismutase (100 μg mL−1) | 100 ± 6 |

| Mn-desferal (300 μm) | 95 ± 15 |

| Mannitol (10 mm) | 121 ± 12 |

| Na-formate (10 mm) | 92 ± 5 |

| Urea (100 mm) | 90 ± 5 |

The H2O2-dependent oxidation of scopoletin by 10 coats from 48-h germinated seeds during a 1-h incubation period was determined in the presence of various inhibitors.

Including 10 μL mL−1 dimethylsulfoxide (ineffective in controls).

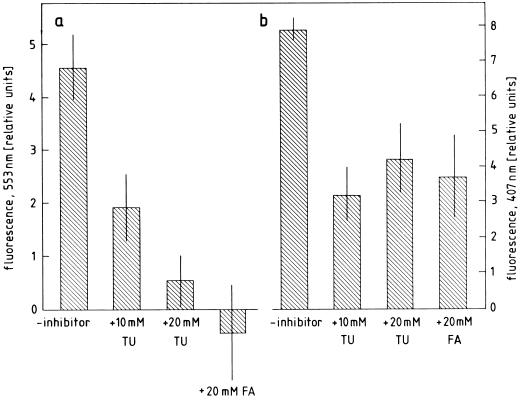

The question arises whether ·OH can be detected as a product of apoplastic oxygen metabolism activated during seed germination. ·OH is an extremely short-lived ROI that has not yet been observed directly in biological systems. Several methods for the indirect estimation of ·OH in chemical reactions have been described that, however, have so far rarely been applied to living plant materials (Babbs, et al., 1989; Kuchitsu et al., 1995; v. Tiedemann, 1997). After modification and careful standardization, the deoxy-Rib degradation assay (Halliwell et al., 1988) and the benzoate hydroxylation assay (Gutteridge, 1987) proved to be suitable for detecting ·OH production by radish seed coats. Deoxy-Rib can be oxidatively cleaved by ·OH to form malondialdehyde reacting with thiobarbituric acid to give an adduct that can be measured fluorometrically. In an alternate manner, ·OH can be reacted with benzoate, resulting in the production of fluorescent hydroxybenzoates, of which 2-hydroxybenzoate is the dominantly fluorescing species at pH < 7 (Baker and Gebicki, 1984; Candeias et al., 1994). The incubation of ROI-producing seed coats in a medium containing deoxy-Rib or benzoate resulted in an increase of fluorescence at the expected wavelengths, which could be inhibited by the ·OH scavengers thiourea and formate (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Demonstration of ·OH release by radish seed coats using the deoxy-Rib degradation assay (a) or benzoate hydroxylation assay (b). Twenty or 10 coats, respectively, from 48-h dark-germinated seeds were incubated for 6 h in darkness in 1.5 mL of buffer containing 20 mm deoxy-Rib or 2.5 mm benzoate and ·OH scavengers (thiourea, TU; formate, FA). Degradation of deoxy-Rib was determined by the increase in fluorescence at 553 nm against a blank without seed coats. Formation of hydroxybenzoates was determined by the increase in fluorescence at 407 nm against a blank without benzoate. The background fluorescence due to benzoate (see Fig. 11) was subtracted.

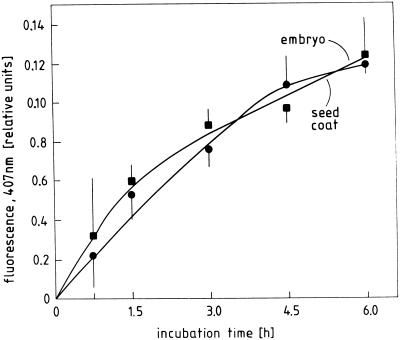

Because of its sensitivity and simplicity, the fluorometric determination of benzoate hydroxylation products (presumably mainly 2-hydroxybenzoate) was chosen for investigating the time course of ·OH production by seed coats and embryos after 48 h of germination in darkness (Fig. 10). The spectrum of the fluorescence increase determined in these experiments showed a peak at 407 nm and was qualitatively indistinguishable from the spectra obtained with 2-hydroxybenzoate or 3-hydroxybenzoate (Fig. 11). Under the conditions of our measurements one relative fluorescence unit (407 nm) was equivalent to a 2-hydroxybezoate concentration of 15 nm or a 3-hydroxybenzoate concentration of 0.9 μm. The fluorescence increase produced by seed coats in benzoate medium could be inhibited by ·OH scavengers (adenine, mannitol, formate, and thiourea), H2O2 scavengers (catalase and KI), O·2− scavengers (superoxide dismutase and Mn-desferal), as well as by peroxidase inhibitors (KCN and NaN3). Urea, employed as an inactive analog of thiourea, had no inhibitory effect even at high concentrations (Table IV). It appears from these results that ·OH can also be generated during the “oxidative burst” of germinating radish seeds. Inhibitor evidence reveals that the ·OH production in this system depends on the availability of O·2−, H2O2, and active peroxidase.

Figure 10.

Time course of ·OH release by embryos and coats of germinating radish seeds. Ten embryos or 10 coats from 48-h dark-germinated seeds were incubated in 1.5 mL of benzoate assay medium in darkness. Data are normalized on a per embryo/seed coat basis.

Figure 11.

Fluorescence emission spectra of benzoate (2.5 mm) and reaction product(s) of the benzoate hydroxylation assay. Radish seed coats were incubated for 6 h in assay medium with or without benzoate as in Figure 10 (a). The spectra of authentic 2-hydroxybenzoate (2-HOB, 0.2 μm), 3-hydroxybenzoate (3-HOB, 10 μm), and 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HOB, 1 mm) are included for comparison (b).

Table IV.

Effect of ROI scavengers and related inhibitors on ·OH release by radish seed coats

| Inhibitor | ·OH Release |

|---|---|

| % | |

| None | 100 ± 5 |

| Catalase (100 μg mL−1) | 45 ± 15 |

| KI (10 mm) | 7 ± 21 |

| Superoxide dismutase (100 μg mL−1) | 30 ± 18 |

| Mn-desferal (300 μm) | 26 ± 29 |

| KCN (1 mm) | −9 ± 23 |

| NaN3 (1 mm) | −14 ± 10 |

| Adenine (10 mm) | 26 ± 10 |

| Mannitol (50 mm) | 54 ± 22 |

| Mannitol (100 mm) | 8 ± 35 |

| Na-formate (10 mm) | 81 ± 8 |

| Na-formate (20 mm) | −35 ± 27 |

| Thiourea (50 mm) | 19 ± 14 |

| Urea (100 mm) | 83 ± 27 |

The ·OH-dependent hydroxylation of benzoate by 10 seed coats from 48-h germinated seeds during a 3-h incubation period was determined in the presence of various inhibitors. Urea served as a negative control.

DISCUSSION

Using a sensitive assay for ROI originally developed for demonstrating the oxidative burst in phagocytic blood cells, this study shows that a similar rise in ROI release is initiated in germinating seeds shortly before the radicle protrudes through the seed coat. Up to now, ROI production by seeds has almost exclusively been considered under the aspect of oxidative stress, causing detrimental effects within seeds such as a loss of viability and germinability (Hendry, 1993; Leprince et al., 1995; Reuzeau and Cavalie, 1995). In contrast to this view it is the intention of the present report to demonstrate that the production of ROI during seed germination in fact represents an active, beneficial biological reaction that is connected with high germination capacity and vigorous seedling development. This view is supported by the finding that a strong rise in ROI release takes place in the healthy, actively germinating seed, which coincides with the period in which the expanding embryo ruptures the coat and becomes exposed to environmental factors such as pathogenic microorganisms. This temporal correlation holds when germination is suppressed or promoted by photomorphogenetic light or hormones such as ABA and GA3, indicating that both events are under a similar kind of developmental control.

The metabolic activity of the seed coat in the mature seed can be ascribed to the aleurone layer, a living tissue covering the inner surface of the coat that is released from the quiescent state together with the germinating embryo (Bewley and Black, 1994). Whereas the role of the aleurone layer as a secretory tissue for hydrolases, peroxidase, and several other enzymes in the caryopses of cereals is well established (Jones and Jacobsen, 1991), very little is known about the morphological counterpart in the seeds of dicotyledonous plants (Yaklich et al., 1992). In galactomannan-storing seeds of legumes such as Trigonella foenum-graecum the aleurone layer secrets galactan- and mannan-degrading hydrolases for the breakdown of these storage polysaccharides in the cell walls of the endosperm during germination (Bewley and Black, 1994). In Brassicaceae that lack a storage endosperm in the mature seeds, the aleurone tissue can be developmentally derived during seed maturation from the inner integument (Bergfeld and Schopfer, 1986) or from the outer layer of the endosperm (Groot and Van Caeseele, 1993). In mustard seed coats, the induction of metabolic activity, including a rapid breakdown of storage protein and storage fat, starts within less than 24 h after sowing in a similar fashion as in the cotyledons of the embryo and is subject to a similar control by light (Bergfeld and Schopfer, 1986). Our experiments with the coats of radish seeds provide evidence that the aleurone layer in the seeds of dicotyledonous plants without bulky endosperm can function as a secretory tissue during germination by releasing ROI and peroxidase to the apoplastic space, presumably as a constitutive defense reaction against infection by microorganisms. In view of the relative chemical inertness of O·2− and H2O2, the effectiveness of this reaction may depend chiefly on the peroxidase-mediated generation of ·OH. Moreover, in view of the emerging role of ROI in signal transduction (Jabs et al., 1997; Alvarez et al., 1998; Chamnongpol et al., 1998), it appears possible that these oxygen species are involved in activating and coordinating various additional defense reactions that give the embryo a pre-emptive advantage for survival in a hazardous environment.

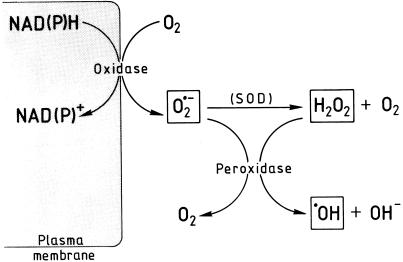

The ROI assay based on DCFH oxidation provides an integral measure for H2O2, ·OH, and O·2− (after its dismutation to H2O2 and O2) and is, therefore, perfectly suited for an overall assessment of ROI production by plant tissues in vivo. However, this strength also represents a major drawback in so far as the assay can give no information on the biosynthetic relationships and interactions between these molecules. The inhibitor evidence obtained with various reagents scavenging one or more of the ROI suggest that all three types of ROI can be produced in germinating radish seeds (Table I). We have tested this supposition by applying appropriate assay reactions for O·2−, H2O2, and ·OH with the result that all three ROI can be identified in the incubation medium of embryos and coats isolated from germinating radish seeds. This conclusion is of course critically dependent on the reliability of the assay reactions used. We have therefore applied various diagnostic radical scavengers and inhibitors to test the specificity of these reactions (Tables II–IV). These tests confirm that the assays employed in this study are suitable for selectively detecting O·2−, H2O2, and ·OH in a mixture of all three ROI. Moreover, the inhibitor data provide information on the biosynthetic relationships between various ROI. This information can be summarized as follows: O·2− is formed by a cyanide-insensitive, DPI-sensitive reaction, pointing to a NAD(P)H-oxidase-type enzyme in the plasma membrane; H2O2 originates from the dismutation of O·2− as its formation can be inhibited by inhibiting O·2− formation with DPI; and ·OH is formed in a cyanide-sensitive reaction depending on the presence of O·2− and H2O2. This points to a Fenton-type reaction catalyzed by apoplastic peroxidase. It has recently been shown that peroxidase, transformed into the perferryl state (Compound III) by O·2−, catalyzes the generation of ·OH from H2O2 (Chen and Schopfer, 1999). Taken together, this information can be qualitatively accommodated in a functional scheme (Fig. 12). Additional work is needed to further test this scheme, e.g. by investigating the quantitative relationships between the reactants involved.

Figure 12.

Tentative qualitative scheme illustrating the biosynthetic relationships between various ROI formed by germinating radish seeds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Culture Conditions

Seeds of radish (Raphanus sativus cv Eterna) were obtained from J. Wagner Markensaaten GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany). Batches of 50 seeds were sown on chromatographic paper soaked with distilled water or hormone solutions (GA3 from Serva, Heidelberg, or ABA from Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) and were incubated at 25°C in darkness or far-red light (standard far-red source, 3.5 Wm−2; Mohr, 1966) as described previously (Schopfer and Plachy, 1984). Hormone solutions were adjusted to pH 6.5 to 6.7 with KOH. Germination in the presence of osmotic stress was determined by incubating seed batches on defined solutions of polyethylene glycol 6000 (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) as described previously (Schopfer and Plachy, 1993). Germination percentage was determined using protrusion of the radicle by more than 2 mm as a criterion (Schopfer and Plachy, 1984). For biochemical assays the seed coats were removed from the seeds with fine forceps, carefully avoiding injuring the embryos. All handling was done under green safe light.

Determination of ROI Release

A working solution containing 50 μm DCFH-diacetate (Serva) in K-phosphate buffer (20 mm, pH 6.0) prepared from a 25 mm DCFH-diacetate solution in acetone was incubated for 15 min at 25°C with 0.1 g L−1 of esterase (from pig liver, Boehringer Mannheim, Germany) for deacetylation. This solution was immediately used for ROI assays by incubating three to 15 embryos or seed coats in 1.5 mL for 15 min at 25°C on a shaker. A 1-mL aliquot of the solution was removed and the increase in fluorescence (excitation: 488 nm, emission: 525 nm) due to the oxidation of DCFH to DCF was measured within a few minutes using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (LS-3B, Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). Blanks without plant material were run in parallel and used for subtracting spontaneous fluorescence changes. Oxidation of DCFH by H2O2 is dependent on peroxidase (Keston and Brandt, 1965). As the addition of horseradish peroxidase to assays with embryos and seed coats had no effect on the measurements, endogenous peroxidase activity was obviously not rate limiting in catalyzing the assay reaction. The fluorescence increase was kept in the linear range of the assay as judged from calibration curves with H2O2 and peroxidase. In this range the fluorescence increase was proportional to the number of seed coats incubated in the assay solution. The fluorescence increase could be completely inhibited by KCN (200 μm) or by boiling the plant material before the assay. ROI scavenging reagents were obtained from Boehringer Mannheim (catalase and superoxide dismutase) or from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). Reagents were adjusted to pH 6.0 with HCl or KOH if necessary.

ROI formation by embryos and seed coats was visualized by embedding them in agar medium (10 g L−1) containing the above reagent solution. Pictures were taken with an epifluorescence microscope (Stemi SV6, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with excitation filter BP 450–490 and emission filter LP 520 using Ektachrome 64T film (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Determination of O·2− Release

Batches of 10 embryos or 20 seed coats were incubated in 1 mL of K-phosphate buffer (20 mm, pH 6.0) containing 500 μm XTT or WST-1 (Polyscience Europe, Eppelheim, Germany) in darkness at 25°C on a shaker (Sutherland and Learmonth, 1997; Berridge and Tan, 1998). The increase in A470 (XTT) or 440 nm (WST-1) in the incubation medium was measured with a Kontron Uvikon 940 spectrophotometer. Reagent blanks (without tissue) and tissue blanks (without reagent) run in parallel were used to correct for unspecific absorbance changes. DPI was obtained from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany). Mn-desferal (green complex) was prepared from deferoxamine mesylate (Sigma) and MnO2 as described by Beyer and Fridovich (1989).

Determination of H2O2 Release

Batches of five embryos or 10 seed coats were preincubated for 30 min in 3 mL of K-phosphate buffer (20 mm, pH 6.0) to remove pre-formed H2O2 and were then incubated in 3 mL of the same buffer containing 5 μm scopoletin (Sigma) and 3 μg mL−1 horseradish peroxidase (Boehringer Mannheim) in darkness at 25°C on a shaker (Andreae, 1955). The decrease in fluorescence (excitation: 346 nm, emission: 455 nm) in the incubation medium was measured using reagent blanks as reference. Fluorescence was transformed into molar H2O2 concentration using a linear calibration curve.

Determination of ·OH Release

Batches of 10 embryos or 10 seed coats were incubated in 1.5 mL of K-phosphate buffer (20 mm, pH 6.0) containing 2.5 mm Na-benzoate (Sigma) in darkness at 25°C on a shaker (Gutteridge, 1987). After clarifying the incubation medium by centrifugation, the increase in fluorescence (excitation: 305 nm, emission: 407 nm) was measured in the fluorescence spectrophotometer using a quartz cell. Blanks without benzoate run in parallel were used to correct for unspecific fluorescence originating from substances eluted from the plant material. A305 in the incubation medium was ≤0.12 and was not significantly higher in blanks, excluding optical artifacts in the fluorescence measurements.

In an alternate manner, ·OH production was estimated as describe by Halliwell et al. (1988) by incubating 20 seed coats in 1.5 mL of buffer containing 20 mm 2-deoxy-D-Rib (Sigma). The formation of the breakdown product malondialdehyde was determined by mixing 0.5 mL of centrifuged incubation medium with 0.5 mL of 2-thiobarbituric acid (Serva; 10 g L−1 in 50 mm NaOH) and 0.5 mL of trichloroacetic acid (28 g L−1). After heating in boiling water for exactly 10 min, cooling in tap water, and clarifying by centrifugation, the reaction product was measured fluorometrically (excitation: 532 nm, emission: 553 nm) against reagent blanks.

Determination of Peroxidase Release

Batches of 20 seed coats removed from seeds 24 h after sowing were transferred to small Petri dishes containing 2 mL of distilled water or hormone solutions at 25°C. After appropriate periods of time the seed coats were blotted with paper towels and were incubated further in dishes with 2 mL of K-phosphate buffer (50 mm, pH 7.0; containing hormones in case of hormone treatments) for 20 min on a shaker. Seeds and seed coats were kept continuously in far-red light or darkness (interrupted for short periods of handling under dim, green safe light). Peroxidase activity in the incubation medium was determined photometrically at 436 nm (25°C) using 0.4 mm guaiacol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 2 mm H2O2 as substrates in K-phosphate buffer (50 mm, pH 7.0) in a total volume of 2.5 mL.

Statistics

Data points represent means of four to 12 independent experiments. ses are indicated except where too small to be shown graphically.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Land Baden-Württemberg (doctoral fellowship to G.F.), and in part by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

LITERATURE CITED

- Able AJ, Guest DI, Sutherland MW. Use of a new tetrazolium-based assay to study the production of superoxide radicals by tobacco cell cultures challenged with avirulent zoospores of Phythophthora parasitica var nicotianae. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:491–499. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan AC, Fluhr R. Two distinct sources of elicited reactive oxygen species in tobacco epidermal cells. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1559–1572. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez ME, Pennell RI, Meijer P-J, Ishikawa A, Dixon RA, Lamb C. Reactive oxygen intermediates mediate a systemic signal network in the establishment of plant immunity. Cell. 1998;92:773–784. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae WA. A sensitive method for the estimation of hydrogen peroxide in biological materials. Nature. 1955;175:859–860. doi: 10.1038/175859a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbs CF, Pham JA, Coolbaugh RC. Lethal hydroxyl radical production in paraquat-treated plants. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:1267–1270. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.4.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CJ, Orlandi EW. Active oxygen in plant pathogenesis. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1995;33:299–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.33.090195.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MS, Gebicki JM. The effect of pH on the conversion of superoxide to hydroxyl free radicals. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;234:258–264. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90348-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass DA, Parce JW, Dechatelet LR, Szejda P, Seeds MC, Thomas M. Flow cytometric studies of oxidative product formation by neutrophils: a graded response to membrane stimulation. J Immunol. 1983;130:1910–1917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergfeld R, Schopfer P. Differentiation of a functional aleurone layer within the seed coat of Sinapis alba L. Ann Bot. 1986;57:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MV, Tan AS. Trans-plasma membrane electron transport: a cellular assay for NADH- and NADPH-oxidase based on extracellular, superoxide-mediated reduction of the sulfonated tetrazolium salt WST-1. Protoplasma. 1998;205:74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bestwick CS, Brown IR, Mansfield JW. Localized changes in peroxidase activity accompany hydrogen peroxide generation during the development of a non-host hypersensitive reaction in lettuce. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1067–1078. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.3.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley JD, Black M. Seeds: Physiology of Development and Germination. Ed 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer WF, Fridovich I. Characterization of a superoxide dismutase mimic prepared from desferrioxamine and MnO2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;271:149–156. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP, Wojtaszek P. Mechanisms for the generation of reactive oxygen species in plant defense: a broad perspective. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1997;51:347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Boveris A, Puntarulo SA, Roy AH, Sánchez RA. Spontaneous chemiluminescence of soybean embryonic axes during imbibition. Plant Physiol. 1984;76:447–451. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candeias LP, Stratford MRL, Wardman P. Formation of hydroxyl radicals on reaction of hypochlorous acid with ferrocyanide, a model iron(II) complex. Free Rad Res. 1994;20:241–249. doi: 10.3109/10715769409147520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Ames BN. Detection of picomole levels of hydroperoxides using a fluorescent dichloroflurescein assay. Anal Biochem. 1983;134:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamnongpol C, Willekens H, Moeder W, Langebartls C, Sandermann H, Van Montagu M, Inzé D, Van Camp W. Defense activation and enhanced pathogen tolerance induced by H2O2 in transgenic tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5818–5823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S-X, Schopfer P. Hydroxyl-radical production in physiological reactions: a novel function of peroxidase. Eur J Biochem. 1999;260:726–735. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Río LA, Pastori GM, Palma JM, Sandalio LM, Sevilla F, Corpas FJ, Jiménez A, López-Huertas E, Hernández JA. The activated oxygen role of peroxisomes in senescence. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:1195–1200. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.4.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doke N, Miura Y, Sanchez LM, Park H-J, Noritake T, Yoshioka H, Kawakita K. The oxidative burst protects plants against pathogen attack: mechanism and role as an emergency signal for plant bio-defense: a review. Gene. 1996;179:45–51. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frahry G, Schopfer P. Hydrogen peroxide production by roots and its stimulation by exogenous NADH. Physiol Plant. 1998a;103:395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Frahry G, Schopfer P. Inhibition of O2-reducing activity of horseradish peroxidase by diphenyleneiodonium. Phytochemistry. 1998b;48:223–227. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(98)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frahry G, Schopfer P. NADH-stimulated, cyanide-resistant superoxide production in maize coleoptiles analyzed with a tetrazolium-based assay. Planta. 2000;212:175–183. doi: 10.1007/s004250000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidrol X, Lin WS, Degousee N, Yip SF, Kush A. Accumulation of reactive oxygen species and oxidation of cytokinin in germinating soybean seeds. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JJ, Loake GJ. Role of reactive oxygen intermediates and cognate redox signaling in disease resistance. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:21–29. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot EP, Van Caeseele LA. The development of the aleurone layer in canola (Brassica napus) Can J Bot. 1993;71:1193–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge JMC. Ferrous-salt-promoted damage to deoxyribose and benzoate: the increased effectiveness of hydroxyl-radical scavengers in the presence of EDTA. Biochem J. 1987;243:709–714. doi: 10.1042/bj2430709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Grootveld M, Gutteridge JMC. Methods for the measurement of hydroxyl radicals in biochemical systems: deoxyribose degradation and aromatic hydroxylation. Methods Biochem Anal. 1988;33:59–90. doi: 10.1002/9780470110546.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Ed 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson LM, Chappell JB. NADPH oxidase of neutrophils. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1273:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(95)00140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry GAF. Oxygen, free radical processes and seed longevity. Seed Sci Res. 1993;3:141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y. Role of gibberellins in phytochrome-mediated lettuce seed germination. In: Takahashi N, Phinney BO, MacMillan J, editors. Gibberellins. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Jabs T. Reactive oxygen intermediates as mediators of programmed cell death in plants and animals. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:231–245. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs T, Tschöpe M, Colling C, Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. Elicitor-stimulated ion fluxes and O2− from the oxidative burst are essential components in triggering defense gene activation and phytoalexin synthesis in parsley. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4800–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RL, Jacobsen JV. Regulation of synthesis and transport of secreted proteins in cereal aleurone. Int Rev Cytol. 1991;126:49–88. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60682-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Henmi K, Ono EI, Hatakeyama S, Iwano M, Satoh H, Shimamoto K. The small GTP-binding protein Rac is a regulator of cell death in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10922–10926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keston AS, Brandt R. The fluorometric analysis of ultramicro quantities of hydrogen peroxide. Anal Biochem. 1965;11:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(65)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MM, Hendry GAF, Atherton NM, Vertucci-Walters CW. Free radical accumulation and lipid peroxidation in testas of rapidly aged soybean seeds: a light-promoted process. Seed Sci Res. 1996;6:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchitsu K, Kosaka H, Shiga T, Shibuya N. EPR evidence for generation of hydroxyl radical triggered by N-acetylchitooligosaccharide elicitor and a protein phosphatase inhibitor in suspension-cultured rice cells. Protoplasma. 1995;188:138–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb C, Dixon RA. The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:251–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leprince O, Vertucci CW, Hendry GAF, Atherton NM. The expression of desiccation-induced damage in orthodox seeds is a function of oxygen and temperature. Physiol Plant. 1995;94:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr H. Untersuchungen zur phytochrominduzierten Photomorphogenese des Senfkeimlings (Sinapis alba L.) Z Pflanzenphysiol. 1966;54:63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Puntarulo S, Galleano M, Sánchez RA, Boveris A. Superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide metabolism in soybean embryonic axes during germination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1074:277–283. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90164-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puntarulo S, Sánchez RA, Boveris A. Hydrogen peroxide metabolism in soybean embryonic axes at the onset of germination. Plant Physiol. 1988;86:626–630. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.2.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitch HD, Privalle CT, Fridovich I. Effects of paraquat on the green alga Dunaliella salina: protection by the mimic of superoxide dismutase, desferal-Mn(IV) Free Rad Biol Med. 1987;3:125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(87)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuzeau C, Cavalie G. Activities of free radical processing enzymes in dry sunflower seeds. New Phytol. 1995;130:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez RA, de Miguel L. Phytochrome promotion of mannan-degrading enzyme activities in the micropylar endosperm of Datura ferox seeds requires the presence of the embryo and gibberellin synthesis. Seed Sci Res. 1997;7:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer P, Plachy C. Control of seed germination by abscisic acid: II. Effect of embryo water uptake in Brassica napus L. Plant Physiol. 1984;76:155–160. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer P, Plachy C. Control of seed germination by abscisic acid: III. Effect on embryo growth potential (minimum turgor pressure) and growth coefficient (cell wall extensibility) in Brassica napus L. Plant Physiol. 1985;77:676–686. doi: 10.1104/pp.77.3.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer P, Plachy C. Photoinhibition of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seed germination: control of growth potential by cell-wall yielding in the embryo. Plant Cell Environ. 1993;16:223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Scott JA, Homcy CJ, Khaw B-A, Rabito CA. Quantitation of intracellular oxidation in a renal epithelial cell line. Free Rad Biol Med. 1988;4:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Craig JS, Kerby KB, Stein BD, Sommerville CS. Expression of an extracellular peroxidase that is induced in barley (Hordeum vulgare) by the powdery mildew pathogen (Erysiphe graminis f. sp. hordei) Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1995;47:407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Simontacchi M, Caro A, Fraga CG, Puntarulo S. Oxidative stress affects α-tocopherol content in soybean embryonic axes upon imbibition and following germination. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:949–953. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland MW, Learmonth BA. The tetrazolium dyes MST and XTT provide new quantitative assays for superoxide and superoxide dismutase. Free Rad Res. 1997;27:283–289. doi: 10.3109/10715769709065766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenhaken R, Rübel C. Cloning of putative subunits of the soybean plasma membrane NADPH oxidase involved in the oxidative burst by antibody expression screening. Protoplasma. 1998;205:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann AV. Evidence for a primary role of active oxygen species in induction of host cell death during infection of bean leaves with Botrytis cinerea. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1997;50:151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Estrella R, Blumwald E, Higgins VJ. Non-specific glycopeptide elicitors of Cladosporium fulvum: evidence for involvement of active oxygen species in elicitor-induced effects on tomato cell suspensions. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1993;42:9–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.3.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszek P. Oxidative burst: an early plant response to pathogen infection. Biochem J. 1997;322:681–692. doi: 10.1042/bj3220681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaklich RW, Vigil EL, Erbe EF, Wergin WP. The fine structure of aleurone cells in the soybean seed coat. Protoplasma. 1992;167:108–119. [Google Scholar]