Abstract

Cytosine methylation at the 5-carbon position is an essential DNA epigenetic mark in many eukaryotic organisms. Although countless structural and functional studies of cytosine methylation have been reported, our understanding of how it influences the nucleosome assembly, structure, and dynamics remains obscure. Here, we investigate the effects of cytosine methylation at CpG sites on nucleosome dynamics and stability. By applying long molecular dynamics simulations on several microsecond time scale, we generate extensive atomistic conformational ensembles of full nucleosomes. Our results reveal that methylation induces pronounced changes in geometry for both linker and nucleosomal DNA, leading to a more curved, under-twisted DNA, narrowing the adjacent minor grooves, and shifting the population equilibrium of sugar-phosphate backbone geometry. These DNA conformational changes are associated with a considerable enhancement of interactions between methylated DNA and the histone octamer, doubling the number of contacts at some key arginines. H2A and H3 tails play important roles in these interactions, especially for DNA methylated nucleosomes. This, in turn, prevents a spontaneous DNA unwrapping of 3–4 helical turns for the methylated nucleosome with truncated histone tails, otherwise observed in the unmethylated system on several microseconds time scale.

INTRODUCTION

DNA methylation plays an essential role in epigenetic signaling, specifically in regulating gene expression, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, genome reprogramming (1), and abnormal methylation patterns are associated with several types of cancer and other diseases (2,3). DNA methylation in human occurs primarily on the fifth carbon atom of cytosine within a CpG dinucleotide, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC). It is estimated that ∼80% of all CpG sites in the human genome are methylated (4). Methyl group on 5mC can directly or indirectly affect interactions with DNA-binding proteins, for example, it can hinder the binding of transcription factors (5) or mediate the binding of methyl-CpG-binding domains that recognize methylated CpG sites (6).

The effects of cytosine methylation on free DNA mechanical properties have been an issue of discussion for the past few years. Single-molecule atomic force microscopy experiments have shown that in the context of short DNA oligonucleotides, 5mC methylation results in either an increase or decrease in DNA structural stability in a manner that is sequence-dependent (7). A recent work using persistence length measurements demonstrates that cytosine methylation leads to longer contour lengths and increased DNA flexibility (8). Additionally, studies using infrared spectroscopy reveal that CpG methylation considerably shifts the equilibrium between different backbone sugar pucker conformations of DNA in solution (9). However, crystallographic experiments suggest that adding a methyl group to cytosine has negligible effects on the overall double-helical DNA structure (10).

DNA methylation may affect the structure of nucleosomes. Indeed, there is plenty of evidence, although contradictory, that DNA methylation can influence the nucleosome assembly (11), its dynamics, stability (12–15), positioning (16,17) and chromatin three-dimensional structure (18). For example, recent single-molecule fluorescence studies relying on in vitro reconstituted nucleosomes and biochemical assays have revealed that DNA methylation promotes nucleosome compaction (12,19) and increases the affinity of histones for DNA (11). However, subsequent studies present some evidence that cytosine methylation leads to a decreased level of compaction of nucleosomal DNA concluding that cytosine methylation probably causes nucleosome mechanical destabilization (13,15). Moreover, X-ray and solid-state nanopore force spectroscopy at the level of mono-nucleosomes report that 5mC methylation does not perturb the structure of the nucleosome core particle and has no effect on nucleosome stability (20,21). In addition to experimental studies, in silico approaches also yield contradictory results of the effects of cytosine methylation on DNA mechanics and nucleosome stability and dynamics. Although previous simulations were performed on relatively short time scales of ∼100 ns, they produced contrasting results that cytosine methylation stiffened DNA (22–24), increased the DNA molecule flexibility (25,26), or had no effect (27).

Therefore, the underlying molecular mechanism of DNA methylation effects on the structure and stability of DNA, nucleosomes and chromatin remains elusive and inconclusive. In this work, we investigated how 5mC methylation modulates the mechanical properties of nucleosomal and linker DNA and affects the nucleosome stability and dynamics. We succeeded in performing multiple all-atom molecular dynamics simulations on a relatively long several microsecond time scale each, totaling in 70 μs. Our results showed that methylated cytosines at CpG sites significantly impacted the DNA geometry inducing undertwisting and underwinding of DNA, leading to a more extensive set of interactions between histones and DNA. This is turn, may explain the restricted capacity of the methylated DNA for spontaneous unwrapping which otherwise is observed for conventional nucleosomes without tails.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of nucleosome structural models with native DNA sequences

The simulation systems consist of four full nucleosome structural models, each includes the nucleosome core particle and two straight 20 bp long DNA duplexes as linkers. The detailed procedure of constructing the nucleosome models can be found in our recently published paper (28). Briefly, to construct a nucleosome model with a DNA sequence from a human gene, we first identified the precise translational positioning of DNA with respect to the histone octamer. To accomplish this, we utilized a nucleosome mapping protocol previously developed and applied to the Micrococcal nuclease (MNase-seq) experimental data (29). We selected 147 bp as the nucleosomal DNA length and the dyad positions were determined as the middle points of all 147 bp fragments (30). After smoothing the mid-fragment counts with 15-bp tri-weight kernel function we obtained the dyad positions with local maximum values of the smoothed counts. The dyad with the highest number of counts within a 30 bp interval was chosen as the representative dyad position. Then a well-positioned nucleosome was identified as the + 1 nucleosome which is located downstream of the transcription start site of the KRAS gene (for comparison TP53 + 1 nucleosome was used as well). Following that, the initial structural model of the nucleosome core particle was built using the high-resolution structure of the nucleosome core particle (PDB ID: 1KX5) (31) as a template with 20 bp linker DNA flanking the core particle on each side. The linker DNA from both ends was linearly extended by adding 20 bp DNA segments using the NAB software (32). The native gene sequences were embedded into the structural nucleosome model using the 3DNA program (33). Then all the CpG sites were methylated on both DNA strands in the constructed methylated nucleosome system. The CpG sites on KRAS sequence are positioned as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. We also performed a shorter simulation (2.5 μs) using a different native DNA sequence from TP53 gene containing 12 CpG sites (Supplementary Figure S26). The histone tails were clipped from the original 1KX5 structure and were linearly extended into the solvent symmetrically oriented with respect to the dyad axis. We used the initial nucleosome model to build unmethylated and methylated nucleosomes.

Molecular dynamics simulation protocol

All MD simulations were performed with the package GROMACS version 2019.3 (34) using the Amber14SB force field for protein and OL15 for nucleic acid parameters (35,36). 5-methylcytosines were modeled using parameters from Lankas et al. (37), which was originally derived for Amber parmbsc0 (38). Simulations were performed in explicit solvent using an Optimal Point Charge (OPC) water model, which was recently shown to reproduce water liquid bulk properties and to provide accuracy improvement in simulations of nucleic acids and intrinsically disordered proteins (39). In each simulation system, the initial structure model was solvated in a box with a minimum distance of 20 Å between the nucleosome atoms and the edges of the box. NaCl was added to the system up to a concentration of 150 mM. The solvated systems were first energy minimized using steepest descent minimization for 10 000 steps, gradually heated to 310 K over the course of 800 ps using restraints, and then equilibrated for a period of 1 ns. After that, the production simulations were carried out in the isobaric-isothermic (NPT) ensemble up to 5 μs, with the temperature maintained at 310 K using the modified Berendsen thermostat (velocity-rescaling) (40) and the pressure maintained at 1 atm using the Parrinello–Rahman barostat (41). A cutoff of 10 Å was applied to short-range non-bonded vdW interactions, and the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) (42) method was used to calculate all long-range electrostatic interactions. Periodic boundary conditions were used. Covalent bonds involving hydrogens were constrained to their equilibrium lengths using the LINCS algorithm (43), allowing a 2.0 fs time step to be employed. Coordinates of the solutes were collected every 100 ps yielding a total of 50 000 frames for further analysis. Supplementary Table S1 shows a summary of all simulation systems. Supplementary Table S2 shows an overview of the volume, number of particles, and simulation performance using GPU-accelerated MD simulations.

Analysis of MD simulation trajectories

MD trajectory snapshots were first processed by performing a root mean square deviation (RMSD) fit of the C-α atoms of histone core (excluding the histone tail regions: residues 1–15 and 119–124 for H2A, 1–29 for H2B, 1–43 for H3 and 1–23 for H4) to the minimized structure of the nucleosome. The first 200 ns frames of each simulation were treated as equilibration periods and were excluded from the analysis. By evaluating the DNA structure in each snapshot from the MD trajectories using the 3DNA software (33), the time courses of the base pair, base-pair step parameters, and major/minor groove widths were acquired. The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values of nucleosomal DNA were calculated for backbone atoms at each time point of the trajectories using the Gromacs inbuilt tools g_rmsf. The local bending angle of a base pair step was calculated using 3D-DART (44). The first (1st) and last (187th) base pairs along the DNA sequence were not included in the analysis. The Delphi program was used to calculate the electrostatic potential along the nucleosomal DNA sequence with the center of the minor groove as a reference point (45). The salt concentration was assigned to 0.15 M, and the dielectric constants for solute and solvent were set to 2 and 80, respectively. A value of 1.4 Å was assigned as the radius of the probe sphere. In-house codes written in Python were developed to quantify the histone-DNA interactions defined by two non-hydrogen atoms from histone and DNA within a distance <4.5 Å. The atomic contacts between DNA and histone molecules that are present in more than 70% of trajectory frames are defined as stable contacts. We also compared the base pair and base-pair step parameters from current simulation trajectories with those from the simulations based on the same force field and water model but using a simulation protocol of AMBER 18 package (32). The results are presented in Supplementary Figures S19 and S20.

RESULTS

DNA methylation prevents DNA unwrapping in nucleosomes

Using a high-resolution X-ray structure of the nucleosome core particle as the template and our previous protocol (46), we built an initial nucleosome model with the native DNA sequence of the KRAS gene that comprises 23 pairs of CpG sites (Supplementary Figure S1) in total including 20 bp linker DNA flanking the core particle on each side (Figure 1A). The methylated nucleosome structure was obtained by converting all cytosines of CpG sites into 5mC (Figure 1B). Considering that the DNA dynamics can be restricted by histone tails, four structural models were constructed based on the combination of the CpG methylation status and presence or absence of histone tails: unNUCnotail, unNUCtail, meNUCnotail, meNUCtail (Supplementary Figure S2). All atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were then conducted for all models, and for each system three independent runs were performed, 12 runs in total, on a five-microsecond time scale each.

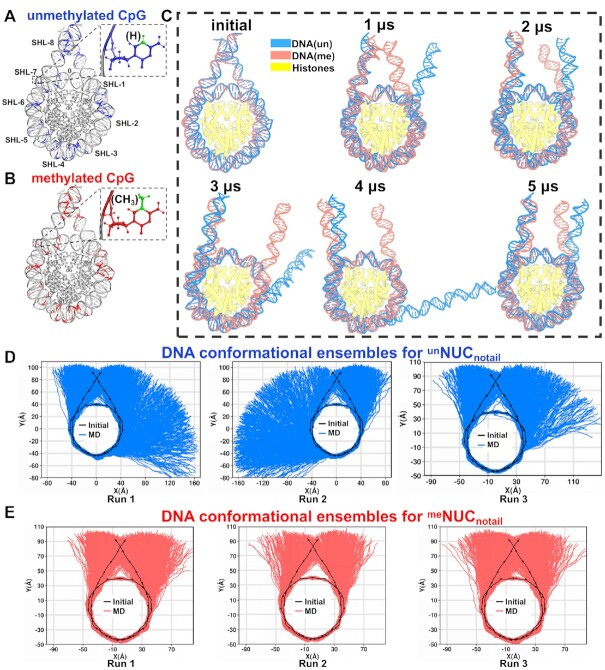

Figure 1.

The dynamics of nucleosomal DNA in systems without histone tails. (A, B) Illustrations of nucleosome systems with unmethylated (blue) and methylated (red) cytosines of the KRAS gene sequence (see Supplementary Figure S1 for the full DNA sequence and methylated CpG sites in detail). (C) Nucleosome conformations of unNUCnotail (blue) and meNUCnotail (red) at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 μs simulation time points for two representative simulations. Two Run #1 simulations from (D) and (E) are used for illustrating the representative conformations of unNUCnotail (blue) and meNUCnotail (red), respectively. (D) The DNA conformational ensembles in three independent unNUCnotail simulation run replicas, five microsecond each. (E) The DNA conformational ensembles in three independent meNUCnotail simulation runs, five microsecond each. The black line and dots indicate the integer and half-integer SHL values of the initial conformation.

We first compare the MD trajectories of DNA in the unNUCnotail and meNUCnotail systems to examine the effect of CpG methylation on nucleosomal DNA structure. The most conspicuous observation is the spontaneous unwrapping of several turns of DNA ends from the histone octamer in unNUCnotail simulations (Figure 1C; Movies 1 and 2). A recent work employed 15 μs MD simulation to a nucleosome core particle without the DNA linkers and revealed the DNA unwrapping of a similar extent in the tailless nucleosomes (47). It's worth mentioning that previous MD simulations on sub-microsecond time scale have not observed the DNA unwrapping (48–50). In our three simulation runs, the unwrapping occurs asymmetrically at only one side of the nucleosome, at either entry or exit DNA sites (Figure 1D). This finding is in line with prior nucleosome simulations characterizing DNA unwrapping and DNA breathing (47,51). As shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S3, for the unmethylated nucleosome systems without tails, noticeable unwrapping starts after 2–3 μs and extends up to SHL ± 4 locations with ∼30 base pairs unwrapped from the octamer. Note that the timing and magnitude of DNA unwrapping are different depending on different simulation runs and there are several occurrences of rewrapping events observed for all three simulation runs in the unmethylated systems. This result is consistent with previous in vitro single-molecule FRET observations and simulations showing that the nucleosomal DNA unwraps asymmetrically under tension and unwrapping on one end stabilizes nucleosomes on another end (23,52). For comparison, we performed another simulation for a nucleosome with TP53 sequence and observed a similar trend (Supplementary Figure S27A).

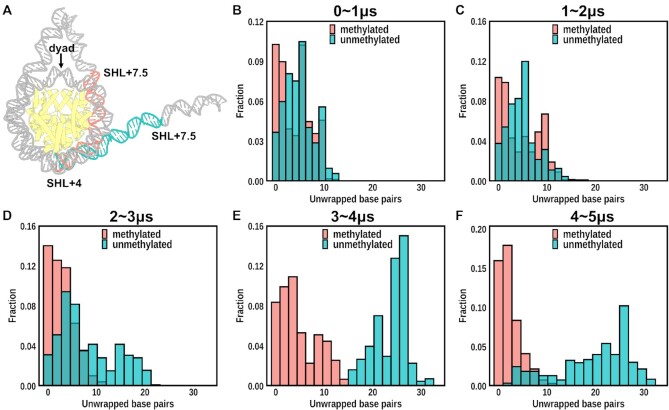

Figure 2.

Time evolution of the number of unwrapped DNA base pairs during simulations for nucleosome systems without tails. (A) The number of unwrapped DNA base pairs were ranged from SHL + 4 to SHL + 7.5 (outer DNA region, see Supplementary Figure S3A for definitions of DNA regions). (B–F) The distributions of the number of unwrapped DNA base pairs for unNUCnotail (green) and meNUCnotail (red) in different time intervals. The y-axis shows the fraction of frames with a certain number of unwrapped base pairs. Out of three unNUCnotail simulation runs, one run with the most extensive DNA unwrapping from the exit side is shown. The simulation runs with the most extensive DNA unwrapping from the entry side are illustrated in Supplementary Figure S3.

In contrast, the number of spontaneously unwrapped DNA base pairs in the methylated system is found to be less than ten, except for several frames exhibiting fast unwrapping and rewrapping motions encompassing of roughly 10–20 bp (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S3). The DNA ends in CpG methylated nucleosomes show dynamic fluctuations but they are unable to achieve unwrapping conformations as the unmethylated systems up to 30 bp unwrapped DNA. These findings demonstrate that DNA methylation at CpG sites may affect the nucleosome dynamics, resulting in more stable and compact nucleosomes whose DNA ends are refractory to unwrap. It is consistent with the prior FRET observations indicating that more compact nucleosomes are induced upon CpG methylation compared to the conventional unmethylated nucleosomes (12,19). Such results are observed for all three meNUCnotail simulation runs (Figure 1E). This result is corroborated for a methylated TP53 nucleosome system with only 12 CpG sites (Supplementary Figure S27B).

It should be noted that all striking DNA unwrapping processes are observed only in the systems in which histone tails were truncated. Various studies previously demonstrated that histone tails considerably restricted the DNA breathing motions and unwinding (49,53–56). Consistent with this, on 5 μs simulation timescale, both unmethylated and methylated nucleosomes with the full histone tails (unNUCtail and meNUCtail) do not yield substantial DNA unwrapping, only a transient detachment of a few base pairs from the histone octamer (Supplementary Figure S4). However, as shown in the next section, both physical properties of DNA and histone-DNA interactions change markedly when methylated cytosines are incorporated for systems either with or without histone tails.

Cytosine methylation changes the DNA geometry

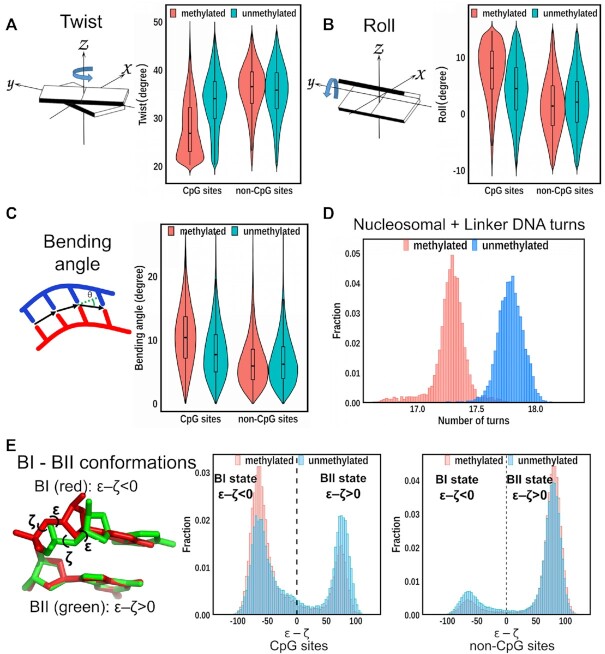

To investigate the molecular mechanism of how cytosine methylation may affect nucleosome stability, we start with the analysis of the local DNA geometrical and conformational properties for nucleosome systems with tails. We first characterize DNA conformations in terms of the base pair (shear, stretch, stagger, buckle, propeller and opening) and base-pair step (roll, tilt, twist, slide, shift and rise) parameters. Out of all DNA structural parameters, roll and twist values at the methylated sites show the most noticeable differences compared to CpG sites for unmethylated system. The distribution of twist values for the methylated steps is considerably shifted towards lower values (average value of twist is decreased by 7° per dinucleotide step, ∼20% decrease) (Figure 3A). This result is corroborated by all six simulation runs. No significant change in twist parameters is observed for non-CpG sites between meNUCtail (red) and unNUCtail systems. To investigate the overall helical twist change of the double-stranded DNA upon CpG methylation, we calculated the number of DNA turns from SHL-9 to SHL+9 which included the linker and nucleosomal DNA regions. The results show that methylated DNA is on average 0.4 turns underwound compared to unmethylated one (Figure 3D). We then determined the underwinding effect for the nucleosomal and linker DNA regions and found in both regions a reduced number of DNA turns in methylated nucleosomes (Supplementary Figure S5). Therefore, we conclude that cytosine methylation results in undertwisting of the DNA double helix, inducing negative stress on both the nucleosomal and linker DNA. DNA undertwisting is regularly accompanied by changes in the rotational and translational positionings of the nucleosomes. A previous study has demonstrated that undertwisting induced by CpG methylation can lead to DNA topological changes and a tighter DNA wrapping around histones (57). It's worth noting that even minor changes in the topological shape of nucleosomes in the promoter regions can substantially impact the efficiency of transcription initiation. Thus, CpG methylation may have a direct effect on regulating the transcription initiation in these regions. Roll is another DNA structural parameter whose value changes considerably upon methylation (Figure 3B). At all CpG steps, roll values increase by an average of 3.5° upon methylation. This increment is consistent with the previous MD simulations of DNA oligomers that produced a similar effect for roll parameters at methylated steps (22).

Figure 3.

Effect of CpG methylation on DNA structural parameters. (A) Left: A schematic diagram of the twist parameter values to describe the relative orientation of two successive base pair planes. Right: Methylation reduces twist values at CpG sites where cytosines are methylated in the meNUCtail systems. Distributions corresponding to twist parameters from unNUCtail and meNUCtail systems are colored in green and red, respectively. No significant changes of twist were observed at non-CpG sites between unNUCtail and meNUCtail systems. The positions of CpG sites and non-CpG sites are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. (B) Same as (A) but for the roll parameter with a schematic diagram of roll shown on the left. The right figure shows that methylation increases roll values at CpG sites. (C) Same as (A) but for the bending angle. The figure shows that methylation induces a more curved DNA with the increased bending angles at CpG sites. (D) Methylation leads to undertwisted DNA and a decreased number of helical turns. The results for unNUCtail and meNUCtail systems are shown in blue and red, respectively. (E) Left: CpG dinucleotide structures illustrate BI (red) and BII (green) conformations based on the sugar-phosphate backbone angles ϵ and ζ. Middle: at CpG sites, DNA methylation (red) shifts the DNA backbone BI/BII equilibrium toward the BI conformations compared to unmethylated CpG sites (blue). Right: No significant changes are observed at non-CpG sites between unmethylated (blue) and methylated (red) systems.

We also calculated the bending angle and observed a systematic increase in bending angle values in all MD runs by 3° on average in methylated compared to unmethylated CpG steps (Figure 3C). It should be noted that no significant correlation is observed between different base-pair step parameters and bending angle values (Supplementary Figure S6). Additionally, the overall curvature for most regions of nucleosomal and linker DNA also increases in the methylated compared to the unmethylated systems (Supplementary Figure S7). In previous experiments performed on DNA oligomers, it has also been shown that DNA methylation can enhance DNA curvature (58). Our data are consistent with this observation, suggesting that DNA methylation produces significant structural bending deformation. Additional inspection of the DNA minor groove widths indicates that the CpG methylation overall narrows the minor groove and widens the major grooves (Supplementary Figures S15–S17). The effects of CpG methylation on all base pair and base-pair step parameters are summarized in Supplementary Figures S8 and S9, respectively. It should be noted that although the effects of cytosine methylation on local DNA geometry are dependent on local sequence context (Supplementary Figure S10 for NUCnotail systems and Supplementary Figure S11 for NUCtail systems), the same tendencies of lowering of an overall twist and increasing of overall roll and bending angle values were observed for a system with TP53 sequence. The changes of these parameters also depend on whether the regions compose linker (free) DNA or nucleosomal DNA. The CpG steps of the linker DNA exhibit more prominent effects upon methylation than those from the nucleosomal DNA (Supplementary Figures S12 and S13).

Besides base-pair step parameters, it is important to characterize the conformation of the DNA sugar-phosphate backbone which is usually described by ϵ and ζ dihedral angles adopting either the canonical BI or BII configurations. As presented in Figure 3E, cytosine methylation shifts the equilibrium at CpG steps toward the BI conformational states and neighboring sites toward the BII conformations (see also Supplementary Figure S14). These BI/BII conformational change results in a shift toward the alternating BII–BI–BII conformation which has been previously shown to have enhanced stability (59).

Cytosine methylation enhances the DNA–histone interactions

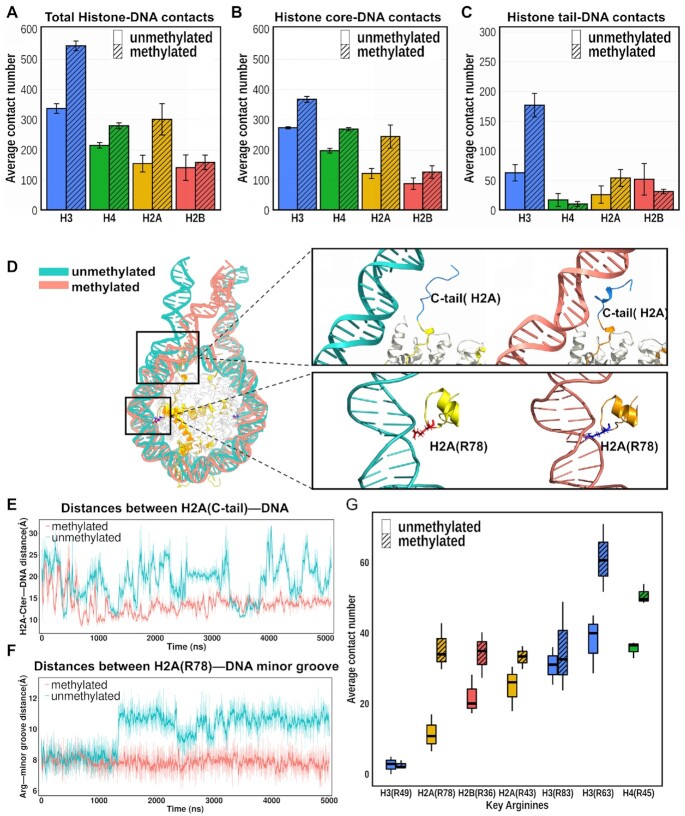

Interactions between histones and DNA play essential roles in regulating nucleosome dynamics and stability. We analyze these interactions and the first striking observation is that the overall number of contacts between histones and DNA is significantly increased upon DNA methylation for all histone types except for H2B in different simulation runs in systems with histone tails (Figure 4A). For systems without histone tails this effect is even more pronounced. The histone core-DNA interactions account for the majority of histone-DNA atom-atom contacts in both meNUCtail and unNUCtail systems (Figure 4B); the remaining contacts come from the interactions between DNA and histone tails (Figure 4C). A detailed inspection of the simulation trajectories reveals that the decreased conformational fluctuations of DNA in the methylated nucleosomes (Supplementary Figure S21), especially DNA regions near the entry/exit sites, provide a potential pathway for DNA stabilization by histone core regions as well as by the H3 N-terminal and H2A C-terminal tails. The detailed characterization of the conformational histone tail ensemble was performed in our recent study (28). In both unNUCtail and meNUCtail systems, the histone tails adopt multiple conformations and are able to bind with DNA at various SHL positions (Movies 3 and 4). A more detailed inspection indicates that positively charged residues, especially arginines and lysines, dominate the interactions between DNA and H3 N-terminal and H2A C-terminal tails (Supplementary Figure S25). Significantly increased contact number is observed in the methylated nucleosomes for a majority of DNA-arginines/lysines interactions in histone tails. Moreover, meNUCtail simulations show that the H2A C-terminal tail makes many stable contacts (see definition in Materials and Methods) with DNA near the entry/exit sites and forms partially compact secondary structures (Figure 4D, E; Movies 3 and 4). These DNA-histone tail interactions can stabilize the nucleosome and decrease the fluctuations at the very ends of the nucleosomal DNA compared to the unNUCtail systems, which may suppress the DNA unwrapping upon methylation.

Figure 4.

Atomic-level interactions between DNA and histones. (A-C) An average number of contacts of histone–DNA interactions in unNUCtail (without stripes) and meNUCtail (with stripes) systems. (A) Interactions for (histone core + histone tails)-DNA. (B) Interactions for histone core–DNA. (C) Interactions for histone tails–DNA. (D) Representative snapshots from MD simulation trajectories showing the interactions between histones and DNA in meNUCtail (red) and unNUCtail (green) nucleosomes. The upper inset shows the interactions between H2A C-terminal tail with DNA and the lower inset shows the interactions between H2A R78 and the DNA minor groove. (E) Time evolution of the distances between the H2A C-terminal tail (the geometric center of amino acid residues from 119 to 128) and the geometric center of DNA segment (base pair positions from –65 to –73 relative to dyad) during the MD simulations. The lines were smoothed with Savitzky-Golay filter using a ten ns window and first-degree polynomial. (F) Time evolution of the distances between the key arginine H2A(R78) and the DNA minor grooves (base pair positions from –58 to –54 relative to dyad) during MD simulations. (G) An average contact number between DNA and the key arginines in the unNUCtail (without stripes) and meNUCtail (with stripes) systems. Locations of each key arginine and their SHL positions relative to the dyad are shown in Supplementary Figure S22. Error bars represent the standard errors calculated from two copies of each type of histone from three independent simulation runs.

Besides, since DNA-histone interactions mainly stem from the insertion of key arginine residues into the DNA minor grooves (Supplementary Figure S22), we examine these specific interactions in detail. We observe that the average number of contacts between the key arginines and DNA is dramatically increased in the methylated systems with or without tails (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figure S23). These differences are especially pronounced for H2A R78 and H2B R36, which interact with the outer DNA turn, where the number of interactions almost doubled. Figure 4F shows the time evolution of the distances between H2A R78 and the DNA minor groove. The side chain from H2A R78 is consistently inserted into the DNA minor groove and rarely loses contacts in the methylated nucleosome systems. However, the contacts between H2A R78 and DNA are disrupted in many frames of the unmethylated systems (Figure 4F, see Supplementary Figure S24 for all three simulation runs). This increase in the number of contacts is accompanied by the decrease in minor groove widths by ∼1–1.5 Angstroms where key arginines H2A R78, H2B R36 and H3 R63 are inserted (Supplementary Figures S17 and S22). A previous study based on DNase-seq experiments has also reported that cytosine methylation induced narrowing of the minor groove (60). It's reasonable to assume that narrowing of the minor groove might increase the negative electrostatic potential in the vicinity of CpG sites and attracts the basic side chains more effectively. It has been previously demonstrated that there is a strong correlation between the minor groove width and the interaction strength between DNA and positively charged residues, especially arginines (61). Indeed, we also found a significant correlation between the minor groove widths and electrostatic potential values mapped to the center of the minor groove as a reference point (Supplementary Figure S18), implying that the narrowed minor groove in methylated nucleosomes enhances the contacts between DNA and nearby key arginines. An increased number of contacts between methylated DNA and histones can explain the decreased DNA fluctuations in the linker and nucleosome entry/exit sites (Supplementary Figure S21). This observation is confirmed for both systems with and without histone tails.

DISCUSSION

Introducing hydrophobic 5mC groups in DNA, which are pointed towards the major grooves on nucleosomal DNA, may dramatically change the geometry, dynamics and hydration patterns of DNA molecules (62). Nevertheless, the atomistic mechanisms of the effects of DNA methylation on nucleosomes and chromatin structure and dynamics at the nucleosomal level remain ambiguous, if not contradictory (7,22,63). In addition, the DNA methylation effects in vivo vary considerably between organisms. In the present study, multiple runs of all-atom MD simulations have been performed to characterize the structural and dynamic differences between conventional and DNA methylated nucleosomes on several microsecond time scale. Our main results indicate that the shape and geometrical properties of DNA are critical in controlling the DNA structure and dynamics as well as its interactions with the histone octamer, which in turn modulate the DNA termini unwrapping and affect nucleosome stability. We show that 5mC leads to the enhanced bending at the CpG steps and enhanced cumulative curvature. DNA methylation is accompanied by changes in dinucleotide step parameters: the increased roll and decreased twist values compared to unmethylated systems. A previous study has demonstrated that the sequence dependent intrinsic DNA curvature and minor groove widths play critical roles in histone-DNA binding and nucleosome formation (64). It was shown both computationally and experimentally that the increased DNA curvature results in lower bending deformation penalty and stronger histone binding affinity with DNA. Moreover, consistent with this previous study, we observe that CpG methylation induces the narrowing of the minor grooves at the adjacent positions of CpG sites, which can result in electrostatic focusing and enhanced interactions with positively charged residues, including key arginines. In regard to the sugar-phosphate backbone geometry, it was previously found that cytosine methylation shifts the population equilibrium of CpG steps toward the BI states due to methyl–sugar steric clashes (25). This, in turn, can increase the intrinsic bending of DNA and reduce the stretching and twist stiffness as shown in both computational (25) and experimental studies (65).

Additionally, we observe the spontaneous unwrapping of unmethylated nucleosomal DNA exposing up to four superhelical turns for tailless nucleosomes in all simulation runs. This result validates the importance of histone tails for maintaining the wrapped nucleosome state (54). It has been previously shown that the removal of histone tails can induce a significant extent of DNA unwrapping from the histone octamer relative to the systems without histone tails (47,66–68). In our simulations, histone tails formed various interactions with the DNA ends to suppress DNA unwrapping in both the conventional and methylated nucleosomes. Even though we did not observe a large difference in terms of unwrapping between methylated and unmethylated systems for nucleosomes with tails, the number of interactions formed by the H2A and H3 tails with DNA ends doubled and tripled respectively in the DNA methylated nucleosomes compared to the conventional unmethylated systems. A recent work has demonstrated that destabilization of the H2A C-terminal tail in CENP-A nucleosomes facilitated DNA unwrapping (69). In addition, previous studies showed that the interactions between histone tails and the DNA ends arise primarily from the H3 and H2A tails. These interactions restrict the DNA end fluctuations and suppress further unwrapping of the nucleosomal DNA by inserting the H2A C-terminal tail into the minor groove and/or by accommodating the long H3 N-terminal tail between the DNA gyres (46,47,51,70). Moreover, we found that not only interactions between DNA and some histone tails are enhanced in the methylated nucleosomes, but the number of key arginines-DNA interactions is also increased, promoting the nucleosome stability and compactness in methylated systems compared to unmethylated ones. Namely, 10 out of 14 key arginines in the methylated nucleosomes with tails form more DNA-histone core contacts than those in the unmethylated systems, among them eight arginines interact with the narrowing minor grooves. All these observations indicate a possibility that the enhanced DNA interactions with the histone core regions as well as histone tails in DNA methylated nucleosomes, especially at the very end of the core DNA, suppress the DNA end fluctuations and unwrapping from the histone octamer.

Based on our findings, the following mechanism emerges: changes in methylated DNA shape, resulting in a more bent and undertwisted DNA with narrowed minor grooves may accommodate additional contacts between DNA and histone octamer, suppressing the DNA unwrapping. It should be mentioned that B-DNA is a right-handed double helix and canonical nucleosomes are left-handed molecules. While the twist may be released during the nucleosome assembly, the cytosine methylation-induced undertwisting can still be introduced on already assembled nucleosomes. Our observations support the experimental data according to which the positive torsional stress destabilizes nucleosomes and negative torsional stress, on the contrary, stabilizes nucleosome formation (71). In addition, a recent computational study has corroborated these findings by applying torsional stress to the nucleosomal DNA for tail-less nucleosomes and demonstrated that DNA unwraps more readily under positive torsional stress (72). It is further shown that in vitro negative supercoiling promotes nucleosome assembly, while positive supercoiling prevents it (73). According to our findings, CpG methylation suppresses the DNA unwrapping from the histone core, which gives rise to a more compact nucleosome as compared with the conventional unmethylated nucleosome. This result is also in agreement with previous single-molecule FRET experiments (12,19), but not consistent with other experimental (13,15) and some computational studies (48). Additionally, our study reveals that overall histone-DNA interactions are greatly enhanced upon CpG methylation. Indeed, it has been previously reported that DNA methylation increases the DNA affinity for histone octamer (74), and enhances nucleosome occupancy (75) and nucleosome stability (76).

It is worth noting that DNA breathing/unwrapping from the histone octamer's surface is sequence dependent (51). Moreover, the positions and number of methylated cytosines could also influence the nucleosome dynamics and stability as well as the magnitude of DNA unwrapping. According to our analysis, although nucleosomal DNA sequence and a number of CpG sites have an effect on the extent of DNA breathing and unwrapping (Supplementary Figure S27), the overall trend of the impact of cytosine methylation is evident—it suppresses DNA unwrapping and breathing.

In summary, we favor the interpretation that it is the combination of overall DNA geometrical and shape properties upon methylation (twist, roll, bending angle, minor/major groove widths, and BI-BII conformational equilibrium) that enhances the interactions with histone cores and tails to form more compact nucleosomes resistant to unwrapping. Our results provide a physical mechanistic explanation of how the CpG methylation may affect the nucleosome structure and dynamics to modulate the DNA accessibility and contribute to the formation of repressive chromatin state. Although we used human DNA sequence in our study, the proposed effects can be extrapolated to other eukaryotic organisms. It should be mentioned, however, that our analysis provides only one side of the story since, in vivo, the impact of DNA methylation is more diverse. Namely, in addition to directly influencing the DNA and nucleosome geometry, their mechanical properties and dynamics, the DNA methylation may recruit or occlude the binding of various specific proteins of the replication and transcription regulatory machineries.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Molecular dynamics simulation trajectories can be accessible at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19087016.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

S.L. and A.R.P. were supported by the Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Queen's University, Canada. A.R.P. is the recipient of a Senior Canada Research Chair in Computational Biology and Biophysics and a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute of Cancer Research, Canada. A.R.P. and S.L. acknowledge the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Y.P. and D.L. were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Library of Medicine at the U.S. National Institutes of Health. This study used the high-performance computational resources from the Compute Canada (https://docs.computecanada.ca) and the Biowulf clusters at the National Institutes of Health (https://hpc.nih.gov/systems).

Contributor Information

Shuxiang Li, Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine, Queen's University, ON, Canada.

Yunhui Peng, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

David Landsman, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Anna R Panchenko, Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine, Queen's University, ON, Canada.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Intramural Research Program of the National Library of Medicine at the U.S. National Institutes ofHealth; Ontario Institute of Cancer Research; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Canada Research Chairs. Funding for open access charge: Ontario Institute of Cancer Research.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jones P.A. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012; 13:484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bergman Y., Cedar H.. DNA methylation dynamics in health and disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013; 20:274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carmona F.J., Davalos V., Vidal E., Gomez A., Heyn H., Hashimoto Y., Vizoso M., Martinez-Cardus A., Sayols S., Ferreira H.J.et al.. A comprehensive DNA methylation profile of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2014; 74:5608–5619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cedar H., Bergman Y.. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009; 10:295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hu S., Wan J., Su Y., Song Q., Zeng Y., Nguyen H.N., Shin J., Cox E., Rho H.S., Woodard C.et al.. DNA methylation presents distinct binding sites for human transcription factors. Elife. 2013; 2:e00726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Straussman R., Nejman D., Roberts D., Steinfeld I., Blum B., Benvenisty N., Simon I., Yakhini Z., Cedar H.. Developmental programming of CpG island methylation profiles in the human genome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009; 16:564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Severin P.M.D., Zou X.Q., Gaub H.E., Schulten K.. Cytosine methylation alters DNA mechanical properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:8740–8751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zaichuk T., Marko J.F.. Single-molecule micromanipulation studies of methylated DNA. Biophys. J. 2021; 120:2148–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Banyay M., Graslund A.. Structural effects of cytosine methylation on DNA sugar pucker studied by FTIR. J. Mol. Biol. 2002; 324:667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Renciuk D., Blacque O., Vorlickova M., Spingler B.. Crystal structures of B-DNA dodecamer containing the epigenetic modifications 5-hydroxymethylcytosine or 5-methylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:9891–9900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee J.Y., Lee J., Yue H., Lee T.H.. Dynamics of nucleosome assembly and effects of DNA methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015; 290:4291–4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choy J.S., Wei S., Lee J.Y., Tan S., Chu S., Lee T.H.. DNA methylation increases nucleosome compaction and rigidity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010; 132:1782–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ngo T.T., Yoo J., Dai Q., Zhang Q., He C., Aksimentiev A., Ha T.. Effects of cytosine modifications on DNA flexibility and nucleosome mechanical stability. Nat. Commun. 2016; 7:10813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collings C.K., Waddell P.J., Anderson J.N.. Effects of DNA methylation on nucleosome stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:2918–2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jimenez-Useche I., Ke J., Tian Y., Shim D., Howell S.C., Qiu X., Yuan C.. DNA methylation regulated nucleosome dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2013; 3:2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chodavarapu R.K., Feng S., Bernatavichute Y.V., Chen P.-Y., Stroud H., Yu Y., Hetzel J.A., Kuo F., Kim J., Cokus S.J.et al.. Relationship between nucleosome positioning and DNA methylation. Nature. 2010; 466:388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Small E.C., Xi L., Wang J.-P., Widom J., Licht J.D.. Single-cell nucleosome mapping reveals the molecular basis of gene expression heterogeneity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 2014; 111:E2462–E2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buitrago D., Labrador M., Arcon J.P., Lema R., Flores O., Esteve-Codina A., Blanc J., Villegas N., Bellido D., Gut M.et al.. Impact of DNA methylation on 3D genome structure. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12:3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee J.Y., Lee T.H.. Effects of DNA methylation on the structure of nucleosomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012; 134:173–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Langecker M., Ivankin A., Carson S., Kinney S.R.M., Simmel F.C., Wanunu M.. Nanopores suggest a negligible influence of CpG methylation on nucleosome packaging and stability. Nano Lett. 2015; 15:783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fujii Y., Wakamori M., Umehara T., Yokoyama S.. Crystal structure of human nucleosome core particle containing enzymatically introduced CpG methylation. FEBS Open Bio. 2016; 6:498–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Perez A., Castellazzi C.L., Battistini F., Collinet K., Flores O., Deniz O., Ruiz M.L., Torrents D., Eritja R., Soler-Lopez M.et al.. Impact of methylation on the physical properties of DNA. Biophys. J. 2012; 102:2140–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ngo T.T.M., Zhang Q.C., Zhou R.B., Yodh J.G., Ha T.. Asymmetric unwrapping of nucleosomes under tension directed by DNA local flexibility. Cell. 2015; 160:1135–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nathan D., Crothers D.M.. Bending and flexibility of methylated and unmethylated EcoRI DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2002; 316:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liebl K., Zacharias M.. How methyl-sugar interactions determine DNA structure and flexibility. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:1132–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carvalho A.T.P., Gouveia L., Kanna C.R., Wärmländer S.K.T.S., Platts J.A., Kamerlin S.C.L.. Understanding the structural and dynamic consequences of DNA epigenetic modifications: computational insights into cytosine methylation and hydroxymethylation. Epigenetics. 2014; 9:1604–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karolak A., van der Vaart A.. Enhanced sampling simulations of DNA step parameters. J. Comput. Chem. 2014; 35:2297–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peng Y.H., Li S.X., Onufriev A., Landsman D., Panchenko A.R.. Binding of regulatory proteins to nucleosomes is modulated by dynamic histone tails. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12:5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pich O., Muinos F., Sabarinathan R., Reyes-Salazar I., Gonzalez-Perez A., Lopez-Bigas N.. Somatic and germline mutation periodicity follow the orientation of the DNA minor groove around nucleosomes. Cell. 2018; 175:1074–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gaffney D.J., McVicker G., Pai A.A., Fondufe-Mittendorf Y.N., Lewellen N., Michelini K., Widom J., Gilad Y., Pritchard J.K.. Controls of nucleosome positioning in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2012; 8:e1003036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davey C.A., Sargent D.F., Luger K., Maeder A.W., Richmond T.J.. Solvent mediated interactions in the structure of the nucleosome core particle at 1.9 a resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2002; 319:1097–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Salomon-Ferrer R., Case D.A., Walker R.C.. An overview of the amber biomolecular simulation package. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2013; 3:198–210. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lu X.-J., Olson W.K.. 3DNA: a versatile, integrated software system for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic-acid structures. Nat. Protoc. 2008; 3:1213–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abraham M.J., Murtola T., Schulz R., Páll S., Smith J.C., Hess B., Lindahl E.. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015; 1:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Galindo-Murillo R., Robertson J.C., Zgarbova M., Sponer J., Otyepka M., Jurecka P., Cheatham T.E.. Assessing the current state of amber force field modifications for DNA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016; 12:4114–4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maier J.A., Martinez C., Kasavajhala K., Wickstrom L., Hauser K.E., Simmerling C.. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015; 11:3696–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lankas F., Cheatham T.E., Spackova N., Hobza P., Langowski J., Sponer J.. Critical effect of the N2 amino group on structure, dynamics, and elasticity of DNA polypurine tracts. Biophys. J. 2002; 82:2592–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pérez A., Marchán I., Svozil D., Sponer J., Cheatham T.E., Laughton C.A., Orozco M.. Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: improving the description of α/γ conformers. Biophys. J. 2007; 92:3817–3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Izadi S., Anandakrishnan R., Onufriev A.V.. Building water models: a different approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014; 5:3863–3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M.. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007; 126:014101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parrinello M., Rahman A.. Polymorphic transitions in single-crystals - a New molecular-dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981; 52:7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M.L., Darden T., Lee H., Pedersen L.G.. A smooth particle mesh ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995; 103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H.J.C., Fraaije J.G.E.M.. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997; 18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 44. van Dijk M., Bonvin A.M.J.J.. 3D-DART: a DNA structure modelling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:W235–W239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li C., Jia Z., Chakravorty A., Pahari S., Peng Y.H., Basu S., Koirala M., Panday S.K., Petukh M., Li L.et al.. DelPhi suite: new developments and review of functionalities. J. Comput. Chem. 2019; 40:2502–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shaytan A.K., Armeev G.A., Goncearenco A., Zhurkin V.B., Landsman D., Panchenko A.R.. Coupling between histone conformations and DNA geometry in nucleosomes on a microsecond timescale: atomistic insights into nucleosome functions. J. Mol. Biol. 2016; 428:221–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Armeev G.A., Kniazeva A.S., Komarova G.A., Kirpichnikov M.P., Shaytan A.K.. Histone dynamics mediate DNA unwrapping and sliding in nucleosomes. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12:2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Portella G., Battistini F., Orozco M.. Understanding the connection between epigenetic DNA methylation and nucleosome positioning from computer simulations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013; 9:e1003354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Biswas M., Voltz K., Smith J.C., Langowski J.. Role of histone tails in structural stability of the nucleosome. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011; 7:e1002279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roccatano D., Barthel A., Zacharias M.. Structural flexibility of the nucleosome core particle at atomic resolution studied by molecular dynamics simulation. Biopolymers. 2007; 85:407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huertas J., Scholer H.R., Cojocaru V.. Histone tails cooperate to control the breathing of genomic nucleosomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021; 17:e1009013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Norouzi D., Zhurkin V.B.. Dynamics of chromatin fibers: comparison of monte carlo simulations with force spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2018; 115:1644–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nurse N.P., Jimenez-Useche I., Smith I.T., Yuan C.L.. Clipping of flexible tails of histones H3 and H4 affects the structure and dynamics of the nucleosome. Biophys. J. 2013; 104:1081–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Peng Y., Li S., Landsman D., Panchenko A.R.. Histone tails as signaling antennas of chromatin. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021; 67:153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Parsons T., Zhang B.. Critical role of histone tail entropy in nucleosome unwinding. J. Chem. Phys. 2019; 150:185103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kenzaki H., Takada S.. Partial unwrapping and histone tail dynamics in nucleosome revealed by coarse-grained molecular simulations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015; 11:e1004443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lee J.Y., Lee T.H.. Effects of histone acetylation and CpG methylation on the structure of nucleosomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012; 1824:974–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Diekmann S. DNA methylation can enhance or induce DNA curvature. EMBO J. 1987; 6:4213–4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Djuranovic D., Oguey C., Hartmann B.. The role of DNA structure and dynamics in the recognition of bovine papillomavirus E2 protein target sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2005; 350:184–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lazarovici A., Zhou T.Y., Shafer A., Machado A.C.D., Riley T.R., Sandstrom R., Sabo P.J., Lu Y., Rohs R., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A.et al.. Probing DNA shape and methylation state on a genomic scale with DNase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 2013; 110:6376–6381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rohs R., West S.M., Sosinsky A., Liu P., Mann R.S., Honig B.. The role of DNA shape in protein-DNA recognition. Nature. 2009; 461:1248–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Machado A.C.D., Zhou T.Y., Rao S., Goel P., Rastogi C., Lazarovici A., Bussemaker H.J., Rohs R.. Evolving insights on how cytosine methylation affects protein-DNA binding. Brief. Funct. Genomics. 2015; 14:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hodges-Garcia Y., Hagerman P.J.. Cytosine methylation can induce local distortions in the structure of duplex DNA. Biochemistry. 1992; 31:7595–7599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Freeman G.S., Lequieu J.P., Hinckley D.M., Whitmer J.K., de Pablo J.J.. DNA shape dominates sequence affinity in nucleosome formation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014; 113:168101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pongor C.I., Bianco P., Ferenczy G., Kellermayer R., Kellermayer M.. Optical trapping nanometry of hypermethylated CPG-Island DNA. Biophys. J. 2017; 112:512–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fenley A.T., Adams D.A., Onufriev A.V.. Charge state of the globular histone core controls stability of the nucleosome. Biophys. J. 2010; 99:1577–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Brower-Toland B., Wacker D.A., Fulbright R.M., Lis J.T., Kraus W.L., Wang M.D.. Specific contributions of histone tails and their acetylation to the mechanical stability of nucleosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2005; 346:135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Winogradofft D., Aksimentiev A.. Molecular mechanism of spontaneous nucleosome unraveling. J. Mol. Biol. 2019; 431:323–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ali-Ahmad A., Bilokapić S., Schäfer I.B., Halić M., Sekulić N.. CENP-C unwraps the human CENP-A nucleosome through the H2A C-terminal tail. EMBO Rep. 2019; 20:e48913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Li Z.H., Kono H.. Distinct roles of histone H3 and H2A tails in nucleosome stability. Sci. Rep. 2016; 6:31437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Teves S.S., Henikoff S.. Transcription-generated torsional stress destabilizes nucleosomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014; 21:88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ishida H., Kono H.. Torsional stress can regulate the unwrapping of two outer half superhelical turns of nucleosomal DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 2021; 118:e2020452118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gupta P., Zlatanova J., Tomschik M.. Nucleosome assembly depends on the torsion in the DNA molecule: a magnetic tweezers study. Biophys. J. 2009; 97:3150–3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lee J.Y., Lee J., Yue H., Lee T.H.. Dynamics of nucleosome assembly and effects of DNA methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015; 290:4291–4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Collings C.K., Waddell P.J., Anderson J.N.. Effects of DNA methylation on nucleosome stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:2918–2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Teif V.B., Beshnova D.A., Vainshtein Y., Marth C., Mallm J.P., Hofer T., Rippe K.. Nucleosome repositioning links DNA (de)methylation and differential CTCF binding during stem cell development. Genome Res. 2014; 24:1285–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Molecular dynamics simulation trajectories can be accessible at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19087016.