Letter-to-the-editor

An increased all-cause mortality beyond previous years’ levels was reported for several European countries within the first half of 2020 corresponding to the early phase of the Severe acute respiratory syndrome-Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic.1 However, more recent studies suggested that excess mortality was only partly to be explained by deaths directly attributed to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).2 In this light, our group investigated temporal evolution of excess deaths showing an additional increase in mortality in the second half of 2020 in Germany, which did not correspond with the number of deaths directly related to SARS-CoV-2-infections.3 With the current letter, we expand this analysis by examining data through December 2021 in the ongoing pandemic situation.

Nationwide open access data from the German Federal Bureau of Statistics depicted daily and weekly all-cause deaths.4 Data of full weeks from January to December 2021 was extracted and compared to averaged death counts from corresponding weeks in 2016–2019 representing the pre-pandemic control period. Emerging SARS-CoV-2-infections and deaths attributed to COVID-19 were daily reported by the Robert-Koch-Institute (RKI).5 Information on SARS-CoV-2-infections was gathered from July 2020 on to examine a lagged influence on mortality. Incidences of infections per 100,000 inhabitants within a federal state were used to calculate tertiles defining low, intermediate and high COVID-19 case volume. Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing curves (LOESS, degree of smoothing α = 0.25) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were fitted illustrating daily fatalities. Inferential statistics were based on generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) and Poisson GLMMs with log link function. Effects were estimated with the lme4 package (version 1.1–26) in the R environment for statistical computing (version 4.0.2). Varying intercepts were specified for random factors. Another model was employed for each factor with the variables period, treatment contrasts for the factor levels and the corresponding interactions. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs, calculated by exponentiation of the regression coefficients) were reported with 95% CIs. Mortality prediction implementing lagged SARS-CoV-2-infection rates and the computation of sliding IRRs were performed via Poisson GLMMs. For the calculation of sliding IRRs for a 12-week range, the dataset has been expanded by mortality data of 2020.

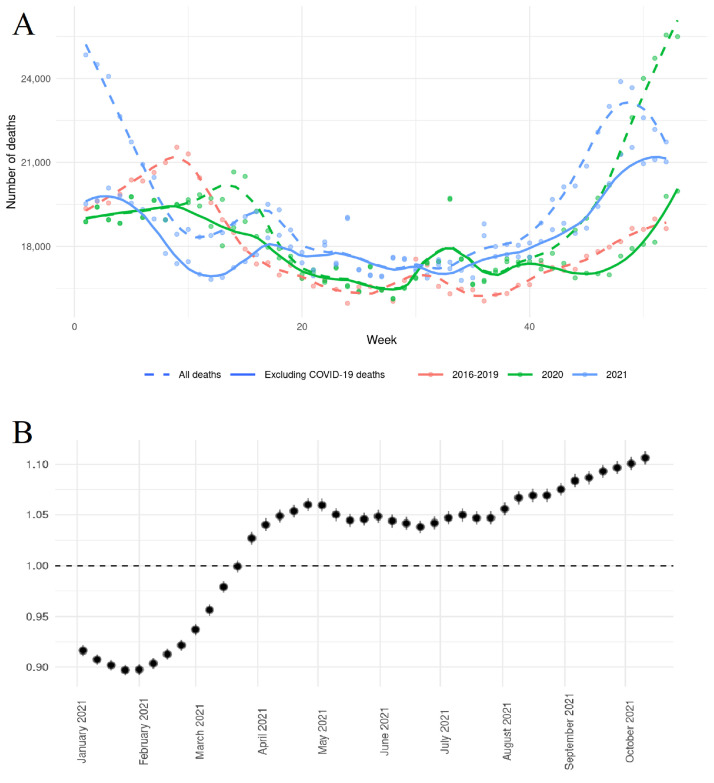

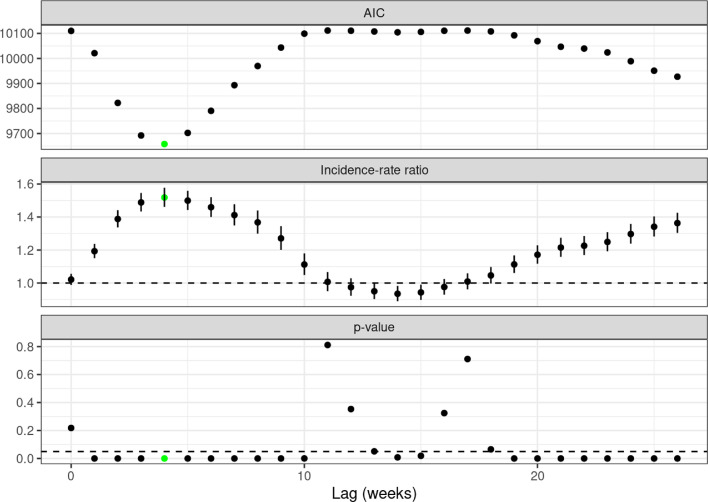

Compared to previous years, there was an overall excess all-cause mortality (IRR 1.090, 95%CI 1.087–1.093, p < 0.01) that persisted after the exclusion of deaths officially attributed to COVID-19 (IRR 1.022, 95%CI 1.019–1.025, p < 0.01). The latter was driven by an increase in daily deaths between the end of April and July and between August and December as illustrated by LOESS curves (Fig. 1 , Panel A). Calculating sliding IRRs for 12-week intervals (Fig. 1, Panel B), a reduced risk of all-cause death excluding COVID-19-attributed fatalities was shown for the first months in 2021 (period 1: 01/04/2021–03/21/2021, IRR 0.922, 95%CI 0.916–0.927, p < 0.01), while there was an ongoing increase of IRRs from the end of March on (period 2: 03/29/2021–01/02/2022, IRR 1.059, 95%CI 1.056–1.063, p < 0.01). Non-COVID-19-attributed mortality was associated with higher age (≥ 80 years, IRR for interaction 1.154, 95%CI 1.122–1.187, p < 0.01), male sex (IRR for interaction 1.033, 95%CI 1.027–1.039, p < 0.01) and treatment in a region with higher COVID-19 case volume (IRR for interaction 1.018, 95%CI 1.012–1.025, p < 0.01). These associations were consistent when analyzing the two different periods in 2021 that were based on the sliding IRR analysis. When calculating prediction models for all-cause mortality including age, gender, weekly indices and the number of SARS-CoV-2-infections with different preceding time intervals, lagged infection incidences had a significant influence on mortality with the strongest influence after a delay of 4 weeks (Fig. 2 ). Another increase in IRRs for mortality was related to the incidence of SARS-CoV-2-infections after a lag of 19 weeks and more.

Fig. 1.

LOESS curves for weekly mortality counts comparing 2016–2019 with 2020 and 2021 (Panel A). Sliding IRR analysis of all-cause mortality for 12-week intervals (dots are placed at the starting date of the time interval, bars represent 95% CIs) excluding deaths attributed to SARS-CoV-2 (Panel B).

Fig. 2.

Prediction model for all-cause mortality (excluding SARS-CoV-2-attributed deaths) implementing different lags for incidences of SARS-CoV-2-infections. IRRs are given for an increase of 100,000 SARS-CoV-2-infections.

AIC: Akaike's information criterion (lower values indicate better model performance).

We present an up-to-date analysis comparing mortality statistics for 2021 and a pre-pandemic control period that shows an excess mortality in 2021 even after the exclusion of deaths attributed to COVID-19 cases. This corresponds to the results of our earlier work, although the effect is currently even more pronounced with a significant excess mortality in the second half of 2021.3 Interestingly, an analysis of inpatient data showed no increased in-hospital mortality in a German multicentric hospital database, which could led to the assumption of a shift of deaths to the outpatient setting.6 Both an assumed avoidance of patients to enter the health care system fearing nosocomial viral transmission and extensive changes in patient pathways throughout different disease groups including the widespread postponement of planned procedures could contribute to our findings. This is supported by the observation of a parallel increase of cardiovascular excess mortality and COVID-19-related deaths and the fact that non-COVID-19 excess mortality has been linked to the prevalence of comorbidities in datasets from the United States.7 , 8 The reduction of acute hospitalizations for cardiovascular diseases and the deficit of cardiovascular interventions during the pandemic indicating a lower quality of overall patient care could contribute to the increased cardiovascular death rates. Postponed treatments were also reported in other medical fields including oncology.

Another possible explanation would be an underestimation of COVID-19-related deaths due to a lacking detection of infections.9 In this light, a recent study from Sanmarchi and colleagues found an association of viral test capacity and a divergence of excess mortality and counts of fatal SARS-CoV-2-infections.10 This might be an explanation for the observation that infection incidences are associated with all-cause mortality with a time lag of few weeks even after the exclusion of COVID-19-attributed deaths. Lastly, delayed effects and sequelae of past SARS-CoV-2-infections may contribute to an increased mortality at a later time by different mechanisms, but were likely not counted as COVID-19-related deaths. The late re-increase of IRRs in the analysis of lagged effects of SARS-CoV-2 infections on mortality may reflect such sequelae.

Whatever the reason is, these observations are noteworthy and require a further evaluation in order to adequately respond to it in the future.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Nothing to declare

Acknowledgments

Funding

There has been no funding in connection with this study.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Vestergaard L.S., Nielsen J., Richter L., Schmid D., Bustos N., Braeye T., et al. Excess all-cause mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe - preliminary pooled estimates from the EuroMOMO network. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(26) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.26.2001214. March to April 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallo E., Prosepe I., Lorenzoni G., Acar A.S., Lanera C., Berchialla P., et al. Excess of all-cause mortality is only partially explained by COVID-19 in Veneto (Italy) during spring outbreak. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):797. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10832-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konig S., Hohenstein S., Ueberham L., Hindricks G., Meier-Hellmann A., Kuhlen R., et al. Regional and temporal disparities of excess all-cause mortality for Germany in 2020: is there more than just COVID-19? J Infect. 2021;82(5):186–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Statistisches Bundesamt. Wöchentliche Sterbefallzahlen 2021 [Available from: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Querschnitt/Corona/Gesellschaft/bevoelkerung-sterbefaelle.html. [last access February 3rd 2022]

- 5.Robert-Koch-Insitut. COVID-19: case numbers in Germany https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Fallzahlen.html: Robert-Koch-Institut; [last access February 3rd, 2022]

- 6.Konig S., Pellissier V., Hohenstein S., Leiner J., Hindricks G., Meier-Hellmann A., et al. A comparative analysis of in-hospital mortality per disease groups in Germany Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic from. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48649. 2016 to 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stokes A.C., Lundberg D.J., Elo I.T., Hempstead K., Bor J., Preston S.H. COVID-19 and excess mortality in the United States: a county-level analysis. PLoS Med. 2021;18(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu D., Ozaki A., Virani S.S. Disease-specific excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of weekly US death data for 2020. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(8):1518–1522. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iuliano A.D., Chang H.H., Patel N.N., Threlkel R., Kniss K., Reich J., et al. Estimating under-recognized COVID-19 deaths, United States, March 2020-May 2021 using an excess mortality modelling approach. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2021;1 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanmarchi F., Golinelli D., Lenzi J., Esposito F., Capodici A., Reno C., et al. Exploring the gap between excess mortality and COVID-19 deaths in 67 countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.