Abstract

Purpose

The number of patients ≥ 80 years admitted into critical care is increasing. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) added another challenge for clinical decisions for both admission and limitation of life-sustaining treatments (LLST). We aimed to compare the characteristics and mortality of very old critically ill patients with or without COVID-19 with a focus on LLST.

Methods

Patients 80 years or older with acute respiratory failure were recruited from the VIP2 and COVIP studies. Baseline patient characteristics, interventions in intensive care unit (ICU) and outcomes (30-day survival) were recorded. COVID patients were matched to non-COVID patients based on the following factors: age (± 2 years), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (± 2 points), clinical frailty scale (± 1 point), gender and region on a 1:2 ratio. Specific ICU procedures and LLST were compared between the cohorts by means of cumulative incidence curves taking into account the competing risk of discharge and death.

Results

693 COVID patients were compared to 1393 non-COVID patients. COVID patients were younger, less frail, less severely ill with lower SOFA score, but were treated more often with invasive mechanical ventilation (MV) and had a lower 30-day survival. 404 COVID patients could be matched to 666 non-COVID patients. For COVID patients, withholding and withdrawing of LST were more frequent than for non-COVID and the 30-day survival was almost half compared to non-COVID patients.

Conclusion

Very old COVID patients have a different trajectory than non-COVID patients. Whether this finding is due to a decision policy with more active treatment limitation or to an inherent higher risk of death due to COVID-19 is unclear.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-022-06642-z.

Keywords: Old patients, COVID, Intensive care, Treatment limitation, Mortality

Take-home message

| Very old COVID-19 patients have different characteristics and 1-month survival than non-COVID patients. Increased limitation of life-sustaining treatments might contribute to the reduced survival in COVID-19 patients. |

Introduction

An ageing population leads to more old patients being admitted to intensive care units (ICU) worldwide [1]. Patients ≥ 80 years account for around 20% of all admissions to ICUs and this is projected to increase sharply in the next three decades [2]. This change in ICU patients' characteristics will require substantial resources, while many countries even today are facing a shortage of ICU beds [3–5]. The general challenge coping with old patients is even more acute during periods of surge, such as with the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Previous studies have identified an increased mortality among patients aged 80 years or older [6] and recent studies on COVID-19 patients have confirmed the poor prognosis of critically ill patients in this age group [7]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the old COVID-19 patients may not only have been “selected” prior to admission, but also earlier and more frequent decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment (LLST) during the ICU stay may have been made[8]. Specific tools, such as the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) [9, 10], together with severity assessment using the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score are commonly used, to help the decision-making process [11].

We have combined data from two prospective international studies including patients over 80 years [12]. The first, VIP2 included patients prior to the pandemic (non-COVID patients) [12], while the COVIP study included COVID-19 patients exclusively (COVID group) [13]. The aim of the study was to test the assumption that old patients prior to and during the pandemic received equal treatment and had similar outcomes.

Methods

Study participants and data collection

Participants included in this analysis were enrolled to one of two prospective observational studies of very old intensive care patients (VIP2 and COVIP) [13, 14]. Participating critical care units recruited consecutive admissions of patients over 80 years during a 6-month period in 2018–19 (VIP 2) for non-COVID patients and patients over 70 years with proven SARS-CoV-2 infection from March 2020 to January 2021 (COVIP). The studies were registered at clinicaltrials.gov (VIP2: NCT0337069; COVIP: NCT04321265). The European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) endorsed both studies.

The distribution of participating ICUs and the patients included in each country are presented in supplemental material 2. National coordinators were responsible for the recruitment of ICUs, coordinated national and local ethical permissions, and supervised patient recruitment at the national level. Ethical approval was mandatory for the study participation in each country. Due to the diversity of ethical consent procedures, some countries could recruit patients without informed consent, while others had to collect it at admission.

Patients were followed up until death or up to 30 days after ICU admission. A website was set up to facilitate dissemination of information about the two studies and to allow for data entry using an electronic case report form (eCRF).

Study population

Among patients in the VIP2, we selected patients admitted to the ICU for respiratory failure with or without circulatory failure. These two predefined subgroups accounted for 1393 out of the 3920 patients recruited (35%). In the COVIP study, all patients had proven SARS-CoV-2 infection and were 70 years of age or older. In that study only patients 80 years and over were included in the present analysis, representing 693 patients out of a total of 3289 patients (21%).

Pre-ICU triage was not recorded. To avoid duplication caused by the transfer of a patient from one ICU to another, each patient could only be entered once into the database regardless of readmission, transfer or other reason. This resulted in a single eCRF per patient. The reference date was day 1 of the first admission to an ICU. All consecutive dates were numbered sequentially from the admission date.

Data collection

Centres collected the data online using a eCRF. The SOFA score on admission was calculated either manually or using an online calculator in the eCRF as described previously [15]. The electronic case record form and database ran on a secure server composed and stored at Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

The frailty level prior to the acute illness and hospital admission was assessed using the CFS version 1.0 [15, 16]. The CFS defines nine classes from very fit to terminally ill (1–9). The required information could be obtained from either the patient, the caregiver/family, or hospital records. We used the English version or native language of the CFS. Patients were classified as fit (CFS of 1–3), vulnerable (CFS 4) and frail (CFS of 5 or higher). We found a very high inter-rater agreement (weighted kappa 0.86), in a study including 1923 pairs of assessors from the VIP-2 study [17].

Type and duration of organ support were also documented. This included for respiratory support: invasive mechanical ventilation (MV) and non-invasive ventilation (NIV). High flow nasal oxygen was not considered as NIV. For circulatory support, this included use of vasoactive drugs and for renal support continuous or intermittent renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Outcome measurement

The primary endpoint was the survival-status assessed at 30 days after ICU admission. Data could be retrieved either directly, from the hospital administration system or collected using active follow-up by telephone.

LLST such as withholding or withdrawing life-supporting treatments was documented based on international recommendations and national guidelines [18]. We documented the delay between ICU admission and LLST and the delay between LLST and death.

Role of the funding source

The COVIP study was supported by a grant from Fondation Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris pour la recherche in France. In Norway, the study was supported by a grant from the Health Region West. In addition, the study was funded by a grant from the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) by the European Commission. No further specific funding was received.

Statistical analysis

No formal sample size calculation prior to these two purely observational studies was performed. The analysis plan was finalised prior to any analysis.

Patients’ baseline characteristics were summarised by frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. Comparisons of COVID and non-COVID patients’ characteristics were performed using the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and the χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables as appropriate.

The crude overall survival up to 30 days after ICU admission was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between COVID and non-COVID patients using a log-rank test.

The incidence of organ support and treatment limitations were estimated using cumulative incidence analysis considering ICU death and ICU discharge as competing risks. Comparisons between COVID and non-COVID patients were performed using Gray’s test.

Patients' characteristics were different in COVID and non-COVID patients. To compare survival and incidence of organ support adjusting for patients’ characteristics, COVID patients were matched to non-COVID-selected patients based on the following factors: age (± 2 years), sofa (± 2 points), clinical frailty scale (± 1 point), gender and region on a 1:2 ratio.

Pairs were identified as correlated groups of data with pair identifier marked as cluster in the analysis. Robust sandwich estimators were used to estimate the variance–covariance matrix of the regression coefficient estimates accounting for clustering of patients with pair.

To confirm the results, we assessed the impact of COVID-19 on outcome using propensity score analysis. The same variables used for the matching procedure were used to build the score (namely, age, SOFA, CFS, gender and region). Generalised boosted regression were used to estimate the propensity score and cases were then weighted to estimate the average “COVID” effect. The analysis used the twang package in R.

A multivariate Cox model regression model also quantified independent effect of COVID-19 and other covariates on 30-day survival. This analysis was first performed on the whole sample including COVID and non-COVID patients and repeated separately in the two cohorts.

Two subgroup analyses were performed to compare survival of COVID and non-COVID patients, respectively, in patients receiving respiratory support (either NIV or invasive MV) and in patients without treatment limitation. In these two subgroups, COVID patients were matched to non-COVID patients based on the same matching criteria and using the same ratio.

All p values were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with R 3.2.3 software packages.

Results

A total of 2086 ICU patients ≥ 80 years were included, 1393 from the VIP2 study and 693 from the COVIP study. Most patients were included from countries located in northern Europe, Israel and USA (Supplement 2). The number of patients included in northern Europe, Israel and USA was 78.8% in the non-COVID cohort and 64.9% in the COVID cohort (p < 0.001). In the matched paired analysis, 666 non-COVID patients from the VIP2 study were matched to 404 COVID patients from the COVIP study.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants enrolled in both cohorts.

Table 1.

Patients and ICU stay characteristics in both cohorts

| COVID patients | Non-COVID patients | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 693) | (n = 1393) | ||

| Age | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 82 (80–96) (81–85) | 83 (80–99) (81–87) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 456 (65.8%) | 742 (53.3%) | < 0.0001 |

| Female | 237 (34.2%) | 651 (46.7%) | |

| Frailty | |||

| Fit (CFS 1–3) | 285 (47.2%) | 438 (31.6%) | < 0.0001 |

| Vulnerable (CFS 4) | 104 (17.2%) | 314 (22.6%) | |

| Frail (CFS 5–8) | 215 (35.6%) | 636 (45.8%) | |

| Sofa | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 5 (0–17) (3–8) | 6 (0–18) (4–9) | < 0.0001 |

| ADL (Katz) | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 6 (0–6) (4–6) | 6 (0–6) (4–6) | 0.062 |

| Mechanical ventilation | |||

| Yes | 404 (58.7%) | 724 (52.1%) | 0.005 |

| NIV | |||

| Yes | 215 (31.5%) | 616 (44.4%) | < 0.0001 |

| Vasoactive drugs | |||

| Yes | 392 (57.6%) | 751 (54%) | 0.13 |

| Renal replacement therapy | |||

| Yes | 70 (10.2%) | 148 (10.7%) | 0.81 |

| ICU LOS in alive patients | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 7 (0.08–85) (3.79–14) | 4.65 (0.04–120) (2.11–9.01) | < 0.0001 |

| ICU LOS in dead patients | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 7 (0.04–53) (3.04–13.75) | 5 (0.04–85.5) (2–10.06) | < 0.0002 |

ADL Activity of daily living, CFS clinical frailty scale, NIV non invasive mechanical ventilation, LOS length of stay, LST life sustaining therapy

COVID compared to non-COVID patients were more frequently male, younger, less frail, and less acutely ill according to SOFA score. They also were more likely to be treated with invasive mechanical ventilation, but received less NIV. There was no difference in the use of vasoactive drugs or renal replacement therapy (RRT). Cumulative incidences of organ support are reported in supplemental material 3. The ICU length of stay was longer in COVID compared to non-COVID patients in survivors as well as in non-survivors.

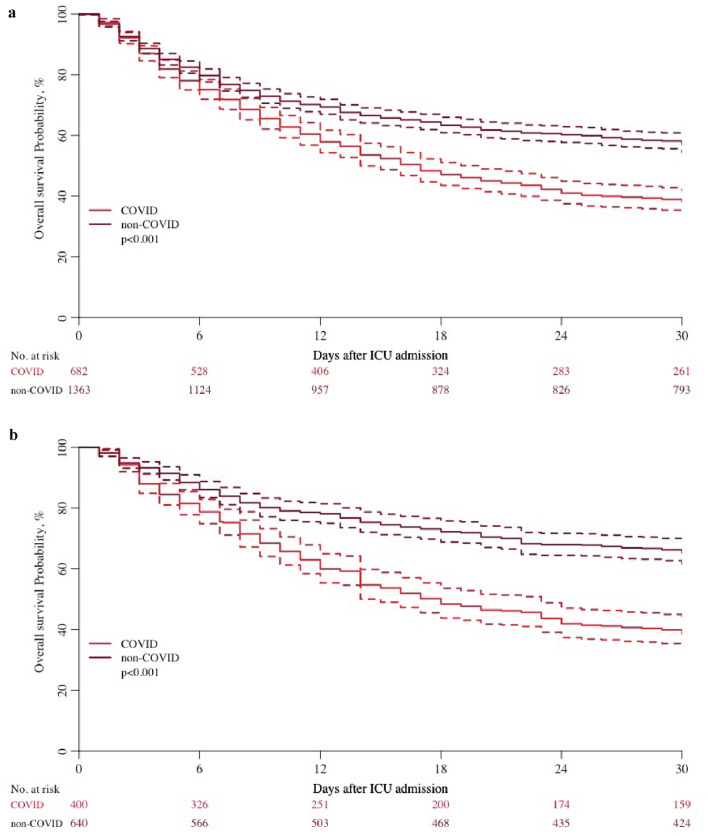

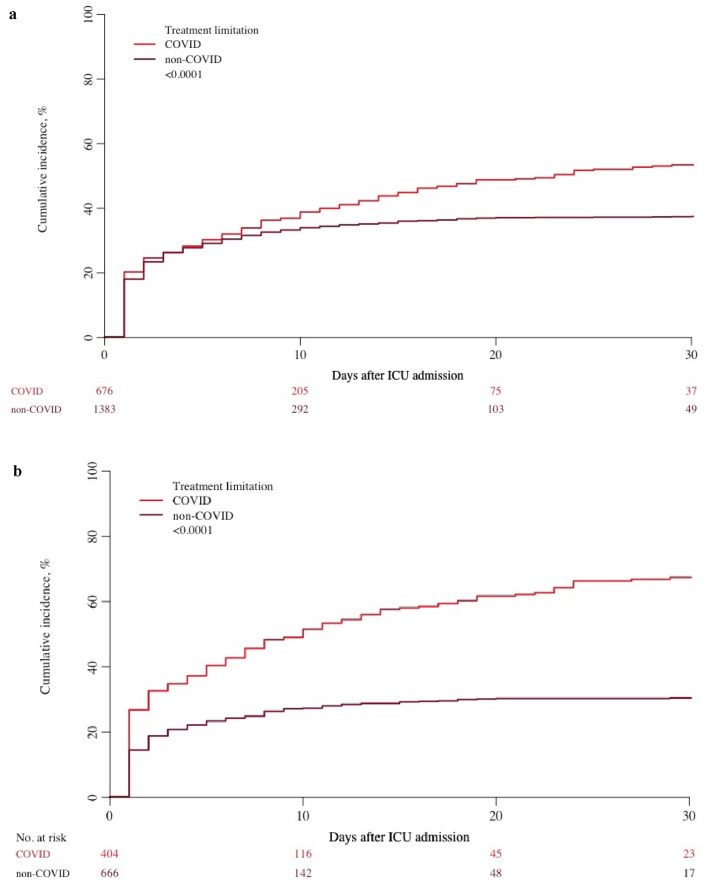

Overall survival was lower among COVID patients (Table 2) (Fig. 1a). At 1 month, survival was only 38% in COVID patients compared with 57% in non-COVID patients. Decisions to limit LST were more frequent among COVID patients (Table 2) (Fig. 2a). The time between ICU admission and withholding of LST was similar in both cohorts, whereas the time between admission and withdrawing was significantly longer in the COVID group.

Table 2.

Survival and limitation of life sustaining treatments in both cohorts

| COVID patients | Non-COVID patients | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 693) | (n = 1393) | ||

| Overall survival (OS) | |||

| At 1 days (range) | 97% (96–98) | 97% (96–98) | < 0.001 |

| At 3 days (range) | 87% (85–90) | 89% (87–90) | |

| At 7 days (range) | 72% (69–75) | 77% (74–79) | |

| At 30 days (range) | 38% (35–42) | 57% (55–60) | |

| Withholding LST | |||

| Yes | 267 (39.1%) | 456 (33.1%) | 0.009 |

| Withdrawing LST | |||

| Yes | 136 (19.9%) | 212 (15.4%) | 0.012 |

| Time admission—withholding | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 2 (− 6 to 50) (1–6) | 1 (− 2 to 80) (1–4) | 0.094 |

| Time withholding—death | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 4 (0–71) (1.5–7) | 3 (0–184) (1–7) | 0.27 |

| Time admission—withdrawing | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 7 (1–46) (4–13) | 4 (1–54) (2–7) | < 0.0001 |

| Time withdrawing—death | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 0 (0–18) (0–1) | 0 (0–165) (0–1) | 0.49 |

ADL Activity of daily living, CFS clinical frailty scale, NIV non invasive mechanical ventilation, LOS length of stay, LST life sustaining therapy

Fig. 1.

Survival curves. a Unpaired analysis. b Matched paired analysis

Fig. 2.

Limitation of life sustaining treatments. a Unpaired analysis. b Matched paired analysis

There were regional differences. In ICUs located in south Europe there was less limitation of Life sustaining treatment, more invasive mechanical ventilation and less non-invasive mechanical ventilation compared with ICUs located in north Europe (SEM5).

404 COVID patients were matched to 666 non-COVID patients. 289 COVID patients could not be matched and were thus excluded from the analysis. Excluded patients were older but with similar 30-day survival (See SEM4). The matched paired analysis reduced most of the baseline differences between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patients and ICU stay characteristics in the matched analysis

| COVID patients | Non-COVID patients | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 404) | (n = 666) | ||

| Age | |||

| Median (range) (IQR) | 82 (80–95) (81–84) | 82 (80–94) (81–84) | 0.33 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 286 (70.8%) | 484 (72.7%) | 0.55 |

| Female | 118 (29.2%) | 182 (27.3%) | |

| Frailty | |||

| Fit (CFS 1–3) | 209 (51.7%) | 360 (54.1%) | 0.51 |

| Vulnerable (CFS 4) | 87 (21.5%) | 149 (22.4%) | |

| Frail (CFS 5–8) | 108 (26.7%) | 157 (23.6%) | |

| Sofa | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 5 (0–15) (3–8) | 5 (0–15) (3–7) | 0.66 |

| Katz | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 6 (0–6) (5–6) | 6 (0–6) (5–6) | 0.93 |

| Mechanical ventilation | |||

| Yes | 225 (56%) | 293 (44%) | < 0.0002 |

| NIV | |||

| Yes | 128 (32.1%) | 335 (50.3%) | < 0.0001 |

| Vasoactive drugs | |||

| Yes | 225 (56.1%) | 323 (48.5%) | 0.019 |

| Renal replacement therapy | |||

| Yes | 36 (9%) | 50 (7.5%) | 0.46 |

| ICU LOS in alive patients | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 7 (0.08–54) (3.4–14.0) | 4.98 (0.08–100) (2.42–9.7) | < 0.0004 |

| ICU LOS in dead patients | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 7.96 (0.08–53) (3.38–14) | 5.92 (0.08–60) (2.08–9.27) | < 0.0009 |

Matched COVID and non-COVID patients have similar age, gender, SOFA, CFS, and activity of daily living (ADL). Invasive mechanical ventilation was more frequent among COVID patients together with vasoactive drugs, while NIV was more frequent among non-COVID patients. The ICU LOS was longer for COVID patients in both survivors and non-survivors. Overall survival was lower among COVID patients (Table 4) (Fig. 1b). At 1 month, survival was 39% among COVID patients, while it was 66% among non-COVID patients.

Table 4.

Survival and limitation of life sustaining treatments in the matched analysis

| COVID patients | Non-COVID patients | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 404) | (n = 666) | ||

| Overall survival (OS) | |||

| At 1 days (range) | 98% (97–100) | 98% (97–99) | < 0.001 |

| At 3 days (range) | 88% (85–91) | 93% (91–95) | |

| At 7 days (range) | 75% (71–80) | 84% (81–87) | |

| At 30 days (range) | 39% (34–44) | 66% (62–70) | |

| Withholding LST | |||

| Yes | 204 (51.1%) | 171 (25.9%) | < 0.0001 |

| Withdrawing LST | |||

| Yes | 103 (25.9%) | 93 (14.1%) | < 0.0001 |

| Time admission—withholding | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 1 (− 6 to 50) (1–6) | 1 (− 2 to 45) (1–4) | 0.36 |

| Time withholding—death | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 4 (0–71) (2–8) | 4 (0–103) (1–7) | 0.35 |

| Time admission—withdrawing | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 7 (1–46) (4–13) | 5 (1–54) (2–7) | < 0.0001 |

| Time withdrawing—death | |||

| Med (range) (IQR) | 0 (0–18) (0–1) | 0 (0–39) (0–1) | 0.72 |

LLST was applied very differently: withholding was applied in 51.1% vs 25.9% and withdrawing 25.9% vs 14.1% in COVID and non-COVID patients, respectively (Table 4). The cumulative incidence of limitation (withholding or withdrawing) 7 days after ICU admission was 43% in COVID patients and 24% in non-COVID patients (Fig. 2b).

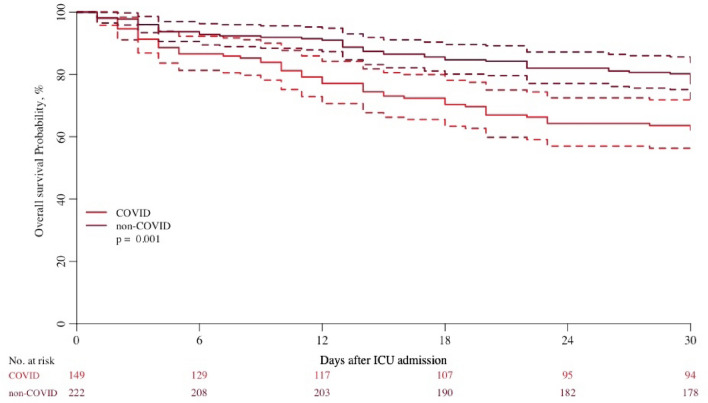

The timing of LST was similar in both cohorts but the delay between withholding treatment and death was longer among COVID patients. In the subgroup analysis of patients without treatment limitation among 392 COVID patients, 152 could be matched to 230 non-COVID patients. Survival was also lower in the COVID patients (Fig. 3) 62% (95%CI 55–71) at day 30 compared to 79% (95%CI 74–85) in non-COVID patients. In the subgroup analysis of patients receiving respiratory support among 374 COVID patients, 195 could be matched to 291 non-COVID patients. Survival was still much lower in the COVID patients (SEM 5).

Fig. 3.

Survival curves in matched subgroup of patients without treatment limitation

The weighted sample built with the propensity score method had similar characteristics for COVID and non-COVID patients (SEM 6) and the weighted hazard ratio (HR) for 1-month survival in non-COVID vs COVID patients was 0.53 (0.46–0.61); p < 0.0001. In the matched sample the estimated for 1-month survival in non-COVID vs COVID patients was 0.46 (0.34–0.62); p < 0.0001. In the multivariate Cox-regression analysis, non-COVID patients also had a better 1-month survival with an HR of 0.50; 95%CI 0.40–0.62; p > 0.00001 (SEM 7).

After adjustment for baseline characteristics, whatever the statistical method used, we found consistent results with lower 30-day survival among COVID patients.

Discussion

In this comparative study, old COVID-19 patients were found to have a substantially higher mortality and had treatment limitations instituted more frequently compared to similar old non-COVID patients. This difference was maintained in a matched pair analysis. The COVID patients demonstrate different baseline characteristics compared with non-COVID patients suggesting a selection bias on admission. Our COVIP cohort includes patients from the first two surges from March 2020 to January 2021. During this period, the shortage of ICU beds prompted drastic actions in many countries: planned surgical activity was almost stopped and ICU capacity was expanded with potential impact on quality of care [19, 20]. An unusually high pressure on ICU bed availability led several countries to issue revised recommendation for ICU admission. Many included age as one of the criteria to be considered [21–23]. However, in most countries age was not a stand-alone factor and chronological age was not considered a legitimate criterion for triage and was only used as part of a combination of risk factors [24]. The rationale for this position was sociocultural respect for the elderly. International guidelines stated that: “even under triage, we must uphold our obligation to care for all patients as best as possible under difficult circumstances” [25].

Given the pressure on the allocation of scarce ICU resources, it is important to analyse the case mix of old patients admitted prior to and during the pandemic. We speculate that selection (pre-ICU triage) of old COVID patients led to patients admitted being less frail, with a higher functional status and a lower disease severity. Hence, patients with a better chance of recovery were admitted with the aim of maximising the number of lives saved. The participating countries were hit differently by the initial phases of the pandemic. Some countries, such as France, were affected much more than others, such as Germany or Norway. A high demand for ICU beds might have contributed to more stringent admission criteria.

This hypothesis is supported by data showing a lower percentage of frail patients among French COVID patients than in other European patients with COVID-19. The percentage of frail patients in the European COVIP study was 20% [14], while it was only 9.1% in the French COVID ICU study [26].

Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment in ICU seem to increase in parallel with the pressure to admit patients to ICU during the pandemic [27].

In addition to a possible stricter selection, COVID patients were more likely to have decisions to limit LST put in place. This result is counter intuitive considering that the COVID patients admitted had a better baseline condition. Withholding of treatment in COVID patients occurred in 39.1% compared with 33.1% in non-COVID patients and withdrawal (including previous WH decisions) in 19.3% compared with 15.4% in non-COVID patients. The difference was even more pronounced in the matched pair analysis with almost twice as many decisions to withhold treatment in COVID compared with non-COVID patients. The results in the non-COVID patients agree with our previous study [28] and with other recent international studies [29, 30] and are in line with a documented relation between treatment limitations and pressure on intensive care units in elderly patients [27]. We provide additional information about the timing of LLST. The delay between ICU admission and LLST was similar in the two groups. The delay between LLST and death was longer among COVID patients compared with non-COVID patients. This suggests that such difficult decisions were protracted in COVID patients translating into longer ICU length of stay.

Changes in end-of-life decision making in ICU over time, have been elegantly shown in a study comparing two time periods from 22 countries [30]. Significantly more treatment limitations occurred in the 2015–2016 cohort compared with the 1999–2000 cohort. Our results together with the results above suggest that we are now more likely to limit LST even if regional variability exits with less LLST in Eastern and Southern countries [31].

Although an increased use of LLST can explain some of the differences in mortality, this is probably not the whole explanation. Since COVID patients in general were less critically ill at admission and had better scores on pre-ICU frailty and ADL, it is also tempting to blame the specific pathophysiology of COVID-19, in particular the rapidly progressive pulmonary failure. This may explain the increased use of MV in this group. In addition, the increased ICU LOS indicates different patient trajectories in old COVID patients [7].

We have not been able to find other published matched pair analyses of elderly COVID-19 vs non-COVID patients, but there are reports comparing patient outcomes from influenza-virus to SARS-CoV-2 virus. In a study from Germany [32] that compared outcomes in 2343 hospitalised COVID-19 patients with 6762 patients admitted with influenza, the overall in-hospital mortality was more than twofold higher in COVID-19 than in influenza patients and the need for ICU admission and MV was also substantially higher. In a study from Mexico, outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients with and without COVID-19 were compared [33] and ICU mortality was 3.7 times higher for patients with COVID-19-induced ARDS compared to similar patients with Influenza A-H1N1. Likewise, the need for ICU admission, length of stay in the ICU, and mortality were also higher among COVID patients compared with Influenza patients in a Finish study [34]. Observations like these confirm the high severity of illness of critically ill COVID-19 patients and are probably also relevant to our findings, although admission status was better.

Decisions to institute LST might have also contributed to the high mortality of COVID patients [35, 36], considering that intensivists would have to work under considerable pressure to increase bed availability [27, 37]. However, in the matched analysis including patients without any limitation of LST, the survival was still lower among COVID patients suggesting that COVID per se carried a higher risk of mortality compared to other causes of acute respiratory failure (Fig. 3).

Our study has several strengths. It included more than 2000 patients from two large prospective international cohorts focusing on patients over the age of 80 with an admission diagnosis of acute respiratory failure. There was no overlap with clear separation between the two time periods, which both occurred in the last 4 years. We documented the organ support provided, LLST and the time when this occurred. We performed a matched analysis including sub studies for mechanically ventilated patients and patients without any LLST. The contribution from different countries enables us to generalise the results to most ICU populations.

This study has several limitations. Recruitment of patients was mainly in European countries. We have no detailed information on the type of treatment that was withheld or withdrawn. For example, a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order does not necessarily result in certain death, whereas a patient denied intubation who requires MV is likely to die. We have no long-term follow-up and no qualitative outcomes, such as health-related quality of life.

It is likely that only the healthiest octogenarians were admitted. However, the duration of treatment was limited by the implementation of limitations in LST. We did not study the mortality of patients aged 80 years and older admitted to the ICU for non-COVID causes during the COVIP inclusion period. As documented in Brazil, we cannot exclude there also being a higher mortality for non-COVID patients during the COVID-19 period [38]

The respective contribution of LLST and intrinsic severity of COVID-19 is hard to disentangle.

Conclusions

We found old COVID patients to be less severely ill and less frail than old non-COVID patients at ICU admission, suggesting an underlying triage process. In the matched paired analysis, decisions to limit LST were almost twice as likely in COVID than in non-COVID patients. The 1-month survival in the COVID patients was almost half that of non-COVID patients. Our results suggest that COVID-19 patients have a more aggressive disease trajectory leading to a reduced 1-month survival.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplemental material 1: List of co-investigators (DOCX 36 KB)

Supplemental material 2: Participating regions and countries (DOCX 13 KB)

Supplemental material 3: Organ supports (DOCX 139 KB)

Supplemental material 4: comparison of survival curves among COVID patients included or excluded from the matched analysis (DOCX 50 KB)

Supplemental material 5: Matched paired analysis: Survival curves among patients with respiratory support (either NIV or invasive MV) (DOCX 19 KB)

Supplemental material 6: patients’ characteristics in propensity score (DOCX 73 KB)

Supplemental material 7: Multivariate analysis of both cohorts merged and each cohort analysed separately (DOCX 15 KB)

Supplemental material 8: Comparison according to location of ICUs according to regions (DOCX 15 KB)

Acknowledgements

List of collaborators COVIP: Philipp Eller, Allgemeine Medizin Intensivstation, Medical University Graz, Graz, Austria. Michael Joannidis, Division of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria. Dieter Mesotten, Department of Intensive Care, Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, Genk, Belgium. Pascal Reper, Department of Intensive Care, CHR Haute Senne, Soignies, Belgium. Sandra Oeyen, Department of Intensive Care, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium. Walter Swinnen, Department of Intensive Care, AZ Sint-Blasius, Dendermonde, Belgium. Helene Brix, Intensiv Behandling, Herlev og Gentofte Hospital, Herlev, Denmark. Jens Brushoej, Intensiv, Slagelse, Slagelse, Denmark. Maja Villefrance, Intensiv, Regionshospitalet Horsens, Horsens, Denmark. Helene Korvenius Nedergaard, Intensive Care Unit, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark. Anders Thais Bjerregaard, Intensive, Sygehus Lillebælt, Kolding, Denmark. Ida Riise Balleby, Intensiv, Regionshospitalet Viborg, Viborg, Denmark. Kasper Andersen, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Sygehus Sønderjylland, Aabenraa, Denmark. Maria Aagaard Hansen, Intensiv Afdeling, Regionshospitalet Herning, Herning, Denmark. Stine Uhrenholt, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Nordsjællands Hospital, Hillerød, Denmark. Helle Bundgaard, Intensiv, Regionshospitalet Randers, Randers, Denmark. Jesper Fjølner, Department of Intensive Care, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark. Aliae AR Mohamed Hussein, Medical ICU and Isolation Centers, Assiut University Hospital, Assiut, Egypt. Rehab Salah, Cardiology ICU, One day surgery hospital, Nasr city, Egypt. Yasmin Khairy NasrEldin Mohamed Ali, MICU, Minia University Hospitals, Minia, Egypt. Kyrillos Wassim, MICU, Quweisna central hospital, Quweisna, Egypt. Yumna A. Elgazzar, MICU, Mayo Isolation Hospital, Cairo Governorate, Egypt. Samar Tharwat, Mansoura university Hospital, Temi El amdid, Mansoura, Egypt. Ahmed Y. Azzam, Alazhar University Hospitals, Cairo, Egypt. Ayman abdelmawgoad habib, intermediate ccu, one day surgery, nasr city, Egypt. Hazem Maarouf Abosheaishaa, MICU, Mostafa Mahmoud Specialized Hospital, Giza, Egypt. Mohammed A Azab, Sherif Mokhtar Cairo University ICU, Kar Al-Ainy Cairo University Hospital, Cairo, Egypt. Susannah Leaver, General Intensive care, St George's University Hospitals NHS Foundation trust, London, England. Arnaud Galbois, Medico-surgical ICU, Hôpital Privé Claude Galien, Quincy sous Sénart, France. Tomas Urbina, Medical intensive care unit, Saint Antoine, Paris, France. Cyril Charron, Medical intensive care unit, Hôpital Ambroise Paré, Boulogne Billancourt, France. Emmanuel Guerot, Medical intensive care unit, Hopital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France. Guillaume Besch, Medico-surgical ICU, CHU de Besançon, Besançon, France. Jean-Philippe Rigaud, Medical intensive care unit, Dieppe General Hospital, Dieppe, France. Julien Maizel, Medical intensive care unit, CHU Amiens, Amiens, France. Michel Djibré, Medico-surgical ICU, Tenon, Paris, France. Philippe Burtin, Surgical ICU, Clinique Du Millenaire, Montpellier, France. Pierre Garcon, Medico-surgical ICU, Marne La Vallee, Jossigny, France. Saad Nseir, Medical intensive care unit, CHU Lille, Lille, France. Xavier Valette, Medical intensive care unit, CHU de Caen, Caen, France. Nica Alexandru, Medico-surgical ICU, Compiegne Noyon Hospital, Compiegne, France. Nathalie Marin, Medical intensive care unit, Cochin, Paris, France. Marie Vaissiere, Medico-surgical ICU, CH Pau, Pau, France. Gaëtan Plantefeve, Medico-surgical ICU, Victor Dupouy, Argenteuil, France. Thierry Vanderlinden, Medical intensive care unit, CH Saint Philibert, Lomme lez Lille, France. Igor Jurcisin, Medico-surgical ICU, Beaujon, Clichy, France. Buno Megarbane, Medical intensive care unit, Lariboisière, Paris, France. Anais Caillard, Surgical ICU, Lariboisière, Paris, France. Arnaud Valent, Surgical ICU, Saint-Louis, Paris, France. Marc Garnier, Surgical ICU, Saint Antoine, Paris, France. Sebastien Besset, Medico-surgical ICU, Louis Mourier, Colombes, France. Johanna Oziel, Medico-surgical ICU, Avicenne, Bobigny, France. Jean-herlé RAPHALEN, Medico-surgical ICU, Centre hospitalier de Versailles, Le Chesnay, France. Stéphane Dauger, Pediatric Intensive and Intermediate Care Unit, Robert Debré, Paris, France. Guillaume Dumas, Medical intensive care unit, Saint-Louis, Paris, France. Bruno Goncalves, Medico-surgical ICU, Sainte-Anne, Paris, France. Gaël Piton, Medical ICU, CHU de Besancon, Besançon, France. Eberhard Barth, Anesthesiologic Intensive Care Department, University Hospital Ulm, Ulm, Germany. Ulrich Goebel, Klinik für Anästhesie und operative Intensivmedizin, St. Franziskus-Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany. Eberhard Barth, IOI-Interdisziplinäre Operative Intensivmedizin, University Hospital Ulm, Ulm, Germany. Anselm Kunstein, MX01, Uniklinik Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany. Michael Schuster, Anästhesie-Intensivstation, Universitätsmedizin der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Mainz, Germany. Martin Welte, Interdiszipinaere Operative Intensivstation, Klinik fuer Anaesthesiologie und operative Intensivmedizin, Klinikum Darmstadt GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany. Matthias Lutz, Internistische Intensivstation, Uniklinik Schleswig Holstein Campus Kiel, Kiel, Germany. Patrick Meybohm, Klinik für Anästhesie und operative Intensivmedizin, University Hospital Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany. Stephan Steiner, ICU, St Vincenz, Limburg, Germany. Tudor Poerner, ITS, Marienhospital Aachen, Aachen, Germany. Hendrik Haake, Internistische Intensivstation I und II, Kliniken Maria Hilf, Mönchengladbach, Germany. Stefan Schaller, 43i, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Stefan Schaller, 44i, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Stefan Schaller, 8i, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Detlef Kindgen-Milles, CIA1, University Hospital Duesseldorf, Duesseldorf, Germany. Christian Meyer, Intensivstation, Evangelisches Krankenhaus Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany. Muhammed Kurt, 32, Florence-Nightingale Krankenhaus, Duesseldorf, Germany. Karl Friedrich Kuhn, 144i, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Winfried Randerath, Intensivpflege Bethanien, Krankenhaus Bethanien GmbH, Solingen, Solingen, Germany. Jakob Wollborn, Anaesthesiologiesche Intensivtherapiestation, Medical Center—University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany. Zouhir Dindane, Interdisziplinäre Intensivstation, Städtische Kliniken Mönchengladbach, Mönchengladbach, Germany. Hans-Joachim Kabitz, I01, Klinikum Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany. Ingo Voigt, Kardiologisch-internistische Intensivstation, Elisabeth-Krankenhaus Essen, Essen, Germany. Gonxhe Shala, Station 2, Johanna Etienne Krankenhaus, Neuss, Germany. Andreas Faltlhauser, Interdisziplinäre Intensivmedizin, Kliniken Nordoberpfalz AG, Klinikum Weiden, Weiden, Germany. Nikoletta Rovina, ICU 1st Department of Pulmonary Medicine Athens Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Sotiria Hospital, Athens, Greece. Zoi Aidoni, ICU, University General Hospital Ahepa, Thessaloniki, Greece. Evangelia Chrisanthopoulou, 2nd Department of Critical Care, UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL (ATTIKON), Haidari, Greece. Antonios Papadogoulas, ICU, GENERAL HOSPITAL OF LARISSA, Larissa, Greece. Mohan Gurjar, Critical Care Medicine, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences (SGPGIMS), Lucknow, India. Ata Mahmoodpoor, General, Imam Reza, Tabriz, Iran. Abdullah khudhur Ahmed, Baghdad teaching hospital, Baghdad, Iraq. Brian Marsh, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. Ahmed Elsaka, Covid ICU, Cork University Hospital, Cork, Ireland. Sigal Sviri, Corona ICU, Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel. Vittoria Comellini, Terapia Intensiva Respiratoria, Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy. Ahmed Rabha, MICU, Askar, Suq Elkamis, Libya. Hazem Ahmed, MICU, Tripoli University Hospital, Tripoli, Libya. Silvio A. Namendys-Silva, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Medicas y Nutricion Salvador Zubiran, Mexico City, Mexico. Abdelilah Ghannam, Service de Réanimation—Institut National d´Oncologie, CHU Ibn Sina de Rabat, Rabat, Morocco. Martijn Groenendijk, ICU Department, Alrijne Zorggroep, Leiderdorp, Netherland. Marieke Zegers, Intensive Care department Radboudumc, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, Netherland. Dylan de Lange, ICU departement, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherland. Alexander Daniel Cornet, Intensive Care Center, Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede, Netherland. Mirjam Evers, ICU Department, Canisius Wilhelmlina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen, Netherland. Lenneke Haas, Intensive care, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherland. Tom Dormans, Zuyderland Heerlen, Zuyderland Medical Center, Heerlen, Netherland. Willem Dieperink, Department of Critical Care, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherland. Luis Romundstad, Department of Critical Care and Emergencies, Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet Medical, Oslo, Norway. Britt Sjøbø, General ICU, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway. Finn H. Andersen, Dept. Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Surgical ICU, Ålesund Hospital, Ålesund, Norway. Hans Frank Strietzel, ICU, Kristiansund Hospital Helse Møre og Romsdal HF, Kristiansund N, Norway. Theresa Olasveengen, Surgical ICU, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway. Michael Hahn, ICU, Haugesund Hospital, Haugesund, Norway. Miroslaw Czuczwar, II Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, First Independent Teaching Hospital No. 1, Lublin, Poland. Ryszard Gawda, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Opole University Hospital, Opole, Poland. Jakub Klimkiewicz, COVID-19 ICU, Military Institute of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland. Maria de Lurdes Campos Santos, Infectious Diseases ICU, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário São João, Porto, Portugal. André Gordinho, Serviço de Medicina Intensiva, Hospital de Beatriz Ângelo, Loures, Portugal. Henrique Santos, D, Centro Hospitalar Tráz os Montes e Alto Dour, Vila Real, Portugal. Rui Assis, Serviço

Author contributions

BG, AB, HF and CJ analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All other authors gave guidance and improved the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was endorsed by the ESICM. Free support for running the electronic database and was granted from Aarhus University, Denmark. The support of the study in France by a grant from Fondation Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris pour la recherche is greatly appreciated. In Norway, the study was supported by a grant from the Health Region West. In addition, the study was supported by a grant from the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC). EOSCsecretariat.eu has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Programme call H2020-INFRAEOSC-05-2018-2019, Grant agreement number 831644. This work was supported by the Forschungskommission of the Medical Faculty of the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf and No. 2020-21 to RRB for a Clinician Scientist Track. No (industry) sponsorship has been received for this investigator-initiated study.

Availability of data and materials

Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article are available to investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by the VIP2 and COVIP steering committee. The anonymised data can be requested from the authors if required.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The primary competent ethics committee was the Ethics Committee of the University of Duesseldorf, Germany. Institutional research ethic board approval was obtained from each study site.

Consent for publication

The manuscript does not contain any individual person's data in any form.

Footnotes

The members of the VIP2, COVIP study groups are listed in acknowledgements.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/31/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s00134-022-06674-5

Contributor Information

Bertrand Guidet, Email: bertrand.guidet@aphp.fr.

the VIP2 and COVIP study groups:

Philipp Eller, Michael Joannidis, Dieter Mesotten, Pascal Reper, Sandra Oeyen, Walter Swinnen, Helene Brix, Jens Brushoej, Maja Villefrance, Helene Korvenius Nedergaard, Anders Thais Bjerregaard, Ida Riise Balleby, Kasper Andersen, Maria Aagaard Hansen, Stine Uhrenholt, Helle Bundgaard, Jesper Fjølner, Aliae A. R. Mohamed Hussein, Rehab Salah, Yasmin Khairy Nasr Eldin Mohamed Ali, Kyrillos Wassim, Yumna A Elgazzar, Samar Tharwat, Ahmed Y. Azzam, Ayman Abdelmawgoad Habib, Hazem Maarouf Abosheaishaa, Mohammed A. Azab, Susannah Leaver, Arnaud Galbois, Tomas Urbina, Cyril Charron, Emmanuel Guerot, Guillaume Besch, Jean-Philippe Rigaud, Julien Maizel, Michel Djibré, Philippe Burtin, Pierre Garcon, Saad Nseir, Xavier Valette, Nica Alexandru, Nathalie Marin, Marie Vaissiere, Gaëtan Plantefeve, Thierry Vanderlinden, Igor Jurcisin, Buno Megarbane, Anais Caillard, Arnaud Valent, Marc Garnier, Sebastien Besset, Johanna Oziel, Jean-herlé Raphalen, Stéphane Dauger, Guillaume Dumas, Bruno Goncalves, Gaël Piton, Eberhard Barth, Ulrich Goebel, Eberhard Barth, Anselm Kunstein, Michael Schuster, Martin Welte, Matthias Lutz, Patrick Meybohm, Stephan Steiner, Tudor Poerner, Hendrik Haake, Stefan Schaller, Stefan Schaller, Stefan Schaller, Detlef Kindgen-Milles, Christian Meyer, Muhammed Kurt, Karl Friedrich Kuhn, Winfried Randerath, Jakob Wollborn, Zouhir Dindane, Hans-Joachim Kabitz, Ingo Voigt, Gonxhe Shala, Andreas Faltlhauser, Nikoletta Rovina, Zoi Aidoni, Evangelia Chrisanthopoulou, Antonios Papadogoulas, Mohan Gurjar, Ata Mahmoodpoor, Abdullah Khudhur Ahmed, Brian Marsh, Ahmed Elsaka, Sigal Sviri, Vittoria Comellini, Ahmed Rabha, Hazem Ahmed, Silvio A. Namendys-Silva, Abdelilah Ghannam, Martijn Groenendijk, Marieke Zegers, Dylan de Lange, Alexander Daniel Cornet, Mirjam Evers, Lenneke Haas, Tom Dormans, Willem Dieperink, Luis Romundstad, Britt Sjøbø, Finn H. Andersen, Hans Frank Strietzel, Theresa Olasveengen, Michael Hahn, Miroslaw Czuczwar, Ryszard Gawda, Jakub Klimkiewicz, Maria de Lurdes Campos Santos, André Gordinho, Henrique Santos, Rui Assis, Ana Isabel Pinho Oliveira, Mohamed Raafat Badawy, David Perez-Torres, Gemma Gomà, Mercedes Ibarz Villamayor, Angela Prado Mira, Patricia Jimeno Cubero, Susana Arias Rivera, Teresa Tomasa, David Iglesias, Eric Mayor Vázquez, Cesar Aldecoa, Aida Fernández Ferreira, Begoña Zalba-Etayo, Isabel Canas-Perez, Luis Tamayo-Lomas, Cristina Diaz-Rodriguez, Susana Sancho, Jesús Priego, Enas M. Y. Abualqumboz, Momin Majed Yousuf Hilles, Mahmoud Saleh, Nawfel Ben-Hamouda, Andrea Roberti, Alexander Dullenkopf, Yvan Fleury, Bernardo Bollen Pinto, Joerg C. Schefold, and Mohammed Al-Sadaw

References

- 1.Flaatten H, de Lange DW, Artigas A, Bin D, Moreno R, Christensen S, et al. The status of intensive care medicine research and a future agenda for very old patients in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1319–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4718-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen Y-L, Angus DC, Boumendil A, Guidet B. The challenge of admitting the very elderly to intensive care. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:29. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stelfox HT, Hemmelgarn BR, Bagshaw SM, Gao S, Doig CJ, Nijssen-Jordan C, et al. Intensive Care Unit bed availability and outcomes for hospitalized patients with sudden clinical deterioration. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:467–474. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simchen E, Sprung CL, Galai N, Zitser-Gurevich Y, Bar-Lavi Y, Gurman G, et al. Survival of critically ill patients hospitalized in and out of intensive care units under paucity of intensive care unit beds. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1654–1661. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000133021.22188.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Town JA, Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Huber MT, Kress JP, Edelson DP. Relationship between ICU bed availability, ICU readmission, and cardiac arrest in the general wards. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2037–2041. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guidet B, Vallet H, Boddaert J, de Lange DW, Morandi A, Leblanc G, Artigas A, Flaatten H. Caring for the critically ill patients over 80: a narrative review. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):114. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0458-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dres M, Hajage D, Lebbah S, et al. Characteristics, management and prognosis of elderly patients with COVID-19 admitted in the ICU during the first wave. Insights from the Covid-ICU study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00861-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas LEML. Should we deny ICU admission to the elderly? Ethical considerations in times of COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):321. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03050-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambden S, Laterre PF, Levy MM, Francois B. The SOFA score-development, utility and challenges of accurate assessment in clinical trials. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):374. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2663-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Heerden PV, Beil M, Guidet B, et al. A new multi-national network studying Very old Intensive care Patients (VIPs) Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2021;53(4):1–6. doi: 10.5114/ait.2021.108084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guidet B, de Lange DW, Boumendil A, Leaver S, Watson X, Boulanger C, et al. The contribution of frailty, cognition, activity of daily life and comorbidities on outcome in acutely admitted patients over 80 years in European ICUs: the VIP2 study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:57–69. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05853-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung C, Flaatten H, Fjølner J, et al. on behalf of the COVIP study group. The impact of frailty on survival in elderly intensive care patients with COVID-19—the COVIP study. Crit Care. 2021;25:149. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03551-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flaatten H, et al. The impact of frailty on ICU and 30-day mortality and the level of care in very elderly patients (≥ 80 years) Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1820–1828. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4940-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fronczek J, Polok K, de Lange DW, et al. VIP2 study group. Relationship between the Clinical Frailty Scale and short-term mortality in patients ≥ 80 years old acutely admitted to the ICU: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2021;25:231. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03632-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flaatten H, Guidet B, Andersen FH, et al. VIP2 Study Group. Reliability of the Clinical Frailty Scale in very elderly ICU patients: a prospective European study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00815-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidet B, Hodgson E, Feldman C, et al. The Durban World Congress Ethics Round Table Conference Report: II. Withholding or withdrawing of treatment in elderly patients admitted to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2014;29(6):896–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Depuydt P, Guidet B. Triage policy of severe covid-19 patients: what to do now? Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11:18. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00770-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guidet B, Flaatten H, Leaver S. Age is just a number: how should we triage old patients in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic? Eur J Emerg Med. 2021;28(2):92–94. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid-19 in Italy: ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic's front line. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1873–1875. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2021) COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing COVID-NICE guideline [NG191]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng191. Accessed Oct 2021.

- 23.Azoulay E, Beloucif S, Guidet B, Pateron D, Vivien B, Le Dorze M. Admission decisions to intensive care units in the context of the major Covid-19 Outbreak: local guidance from the COVID-19 Paris-Region Area. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):293. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberg A, Levy-Lahad E, Karni T, Sprung CL. Israeli position paper: triage decisions for severely ill patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chest. 2020;158(6):2278–2281. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maves RC, Downar J, Dichter JR, et al. ACCP Task Force for Mass Critical Care. Triage of Scarce Critical Care Resources in COVID-19 An Implementation Guide for Regional Allocation: An Expert Panel Report of the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 2020;158(1):212–225. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dres M, Hajage D, Lebbah S, et al. COVID-ICU investigators. Characteristics, management, and prognosis of elderly patients with COVID-19 admitted in the ICU during the first wave: insights from the COVID-ICU study: prognosis of COVID-19 elderly critically ill patients in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00861-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung C, Flaatten H, de Lange D, Beil M, Guidet B. The relationship between treatment limitations and pressure on intensive care units in elderly patients. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(1):124–125. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidet B, Flaatten H, Boumendil A, et al. Withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining therapy in older adults (>/= 80 years) admitted to the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1027–1038. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avidan A, Sprung CL, Schefold JC, et al. ETHICUS-2 Study Group. Variations in end-of-life practices in intensive care units worldwide (Ethicus-2): a prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(10):1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sprung CL, Ricou B, Hartog CS, et al. Changes in end-of-life practices in European Intensive Care Units From 1999 to 2016. JAMA. 2019;322(17):1692–1704. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sprung CL, Jennerich AL, Joynt GM, et al. The Influence of Geography, Religion, Religiosity and Institutional Factors on Worldwide End-of-Life Care for the Critically Ill: The WELPICUS Study. J Palliat Care. 2021;5:8258597211002308. doi: 10.1177/08258597211002308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludwig M, Jacob J, Basedow F, Andersohn F, Walker J. Clinical outcomes and characteristics of patients hospitalized for Influenza or COVID-19 in Germany. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernández Cárdenas C, Lugo G, Hernández García D, Pérez-Padilla R. Comparison of the clinical characteristics and mortality in ARDS due to COVID-19 versus ARDS due to Influenza A-H1N1. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.07.21251306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auvinen R, Nohynek H, Syrjänen R, Ollgren J, Kerttula T, Mäntylä J, Ikonen N, Loginov R, Haveri A, Kurkela S, Skogberg K. Comparison of the clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized adult COVID-19 and influenza patients—a prospective observational study. Infect Dis (Lond) 2021;53(2):111–121. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2020.1840623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haniffa R, Beane A, Dongelmans DA, et al. Linking of Global Intensive Care Collaboration (LOGIC). Time to revisit treatment limitations in critical care benchmarking. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(4):e472–e473. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flaatten H, deLange D, Jung C, Beil M, Guidet B. The impact of end-of-life care on ICU outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(5):624–625. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flaatten H, Van Heerden V, Jung C, Beil M, Leaver S, Rhodes A, Guidet B, deLange DW. The good, the bad and the ugly: pandemic priority decisions and triage. J Med Ethics. 2020;47:e75. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zampieri FG, Bastos LSL, Soares M, Salluh JI, Bozza FA. The association of the COVID-19 pandemic and short-term outcomes of non-COVID-19 critically ill patients: an observational cohort study in Brazilian ICUs. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(12):1440–1449. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06528-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material 1: List of co-investigators (DOCX 36 KB)

Supplemental material 2: Participating regions and countries (DOCX 13 KB)

Supplemental material 3: Organ supports (DOCX 139 KB)

Supplemental material 4: comparison of survival curves among COVID patients included or excluded from the matched analysis (DOCX 50 KB)

Supplemental material 5: Matched paired analysis: Survival curves among patients with respiratory support (either NIV or invasive MV) (DOCX 19 KB)

Supplemental material 6: patients’ characteristics in propensity score (DOCX 73 KB)

Supplemental material 7: Multivariate analysis of both cohorts merged and each cohort analysed separately (DOCX 15 KB)

Supplemental material 8: Comparison according to location of ICUs according to regions (DOCX 15 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article are available to investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by the VIP2 and COVIP steering committee. The anonymised data can be requested from the authors if required.