Abstract

The objective was to systematically review the medical literature and comprehensively summarize clinical research performed on biomarkers for pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) and to summarize the studies that have assessed serum biomarkers acutely in determining intracranial lesions on CT in children with TBI. The search strategy included a literature search of PubMed,® MEDLINE,® and the Cochrane Database from 1966 to August 2011, as well as a review of reference lists of identified studies. Search terms used included pediatrics, children, traumatic brain injury, and biomarkers. Any article with biomarkers of traumatic brain injury as a primary focus and containing a pediatric population was included. The search initially identified 167 articles. Of these, 49 met inclusion and exclusion criteria and were critically reviewed. The median sample size was 58 (interquartile range 31–101). The majority of the articles exclusively studied children (36, 74%), and 13 (26%) were studies that included both children and adults in different proportions. There were 99 different biomarkers measured in these 49 studies, and the five most frequently examined biomarkers were S100B (27 studies), neuron-specific enolase (NSE) (15 studies), interleukin (IL)-6 (7 studies), myelin basic protein (MBP) (6 studies), and IL-8 (6 studies). There were six studies that assessed the relationship between serum markers and CT lesions. Two studies found that NSE levels ≥15 ng/mL within 24 h of TBI was associated with intracranial lesions. Four studies using serum S100B were conflicting: two studies found no association with intracranial lesions and two studies found a weak association. The flurry of research in the area over the last decade is encouraging but is limited by small sample sizes, variable practices in sample collection, inconsistent biomarker-related data elements, and disparate outcome measures. Future studies of biomarkers for pediatric TBI will require rigorous and more uniform research methodology, common data elements, and consistent performance measures.

Key words: : biochemical markers; biomarkers; children; CT scanning; diagnosis; head injury; intracranial lesions; pediatric; prognosis proteomics; TBI; traumatic brain injury; trauma, human; sensitivity; specificity; systematic review

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant public health problem with increasing emergency department visits and hospitalizations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that there are 1.7 million children and adults who sustain a TBI annually.1 Of these, 1.4 million are evaluated and released from the emergency department. Almost half a million of these visits (473,947) are made by children aged 0 to 14 years with a 62% increase in fall-related TBI within the last decade.1 Patients who have an alteration in mental status after blunt head trauma are at risk for TBI. Currently, severity grades of mild, moderate, and severe TBI, are defined by using clinical and radiographic indices. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), length of loss of consciousness, and post-traumatic amnesia form some of the clinical criteria, and evidence of intracranial lesions on CT scan or MRI are the basis of the radiographic criteria.

Advances in the understanding of human biochemistry and physiology have provided insight into new pathways by which we can understand TBI. The application of proteomics to brain injury is still in its infancy,2–4 and research is showing evidence for the involvement of protein processes that contribute to secondary injury after TBI. TBI is characterized by an initial insult to the brain followed by a dynamic series of cellular events and cascading protein activities.5 After direct tissue damage, cerebral blood flow and cerebral metabolism (as reflected by cerebral oxygen and glucose consumption) become dysregulated and edema ensues.6,7 Both vasogenic brain edema (caused by disruption of the brain vessels) and cytotoxic brain edema (caused by intracellular water accumulation secondary to ionic pump failure from energy depletion) occur.8

During anaerobic metabolism, lactic acid accumulates and contributes to increased membrane permeability. Moreover, after adenosine triphosphate stores are depleted, energy-dependent membrane ion pumps begin to fail and terminal membrane depolarizations occur along with excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters (such as glutamate).9 The influx of Ca2+,Na+, and K+ leads to destructive intracellular processes, activating lipid peroxidases, proteases, and phospholipases, which in turn increase the intracellular concentration of free fatty acids and free radicals.10 Other cellular mediators that are released include inflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, and complement.11

Accordingly, cell death after TBI may occur via necrosis (direct cellular damage) or via apoptosis (programmed cell death). Elucidation of these biochemical and protein pathways are providing opportunities for diagnostic and therapeutic targets that may eventually be used to monitor neuronal damage and recovery with great potential for clinical applications.12

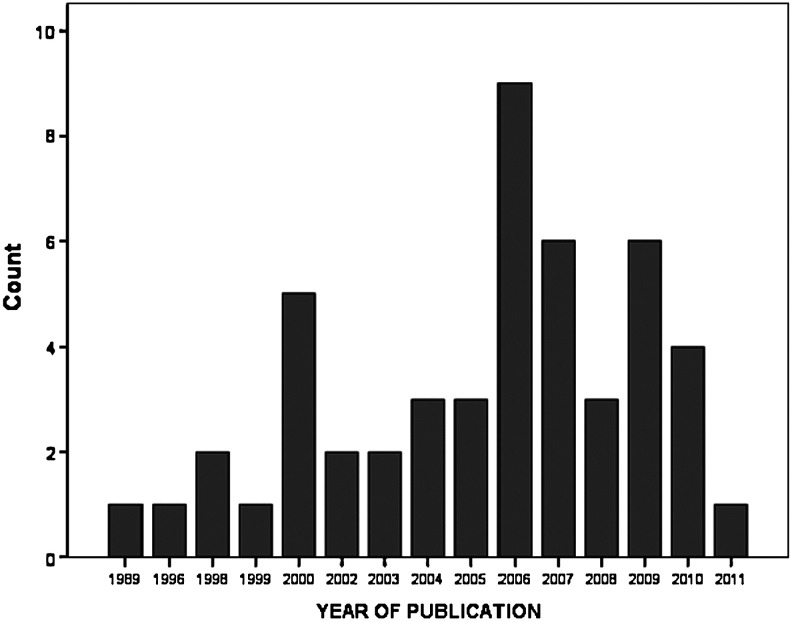

Research in the field of TBI biomarkers has increased exponentially over the last 20 years,13 with most of the publications on the topic of pediatric TBI biomarkers occurring in the last 10 years (Fig. 1). Accordingly, studies assessing biomarkers in pediatric TBI have looked at a number of potential markers that could lend diagnostic, prognostic, as well as therapeutic information. Despite the large number of published studies, there is still a lack of any Food and Drug Administration-approved biomarkers for clinical use in adults and children.14,15 Properties that should be considered when evaluating a biomarker for clinical application include the following: Does the biomarker: (1) demonstrate a high sensitivity and specificity for brain injury; (2) stratify patients by severity of injury; (3) have a rapid appearance in accessible biological fluid; (4) provide information about injury mechanisms; (5) have well-defined biokinetc properties; (6) monitor progress of disease and response to treatment; and (7) predict functional outcome.14

FIG. 1.

Distribution, by year of publication, of studies in human pediatric traumatic brain injury biomarkers included in this systematic review.

Through a systematic review of the medical literature, this article will comprehensively summarize the clinical research done in biomarkers for pediatric TBI, specifically those biomarkers found in biofluids. In addition, this review will summarize the studies that have assessed serum biomarkers acutely in determining intracranial lesions on CT in children with TBI. The ability to detect children with intracranial lesions on CT would contribute significantly to the acute care of children with suspected TBI by reducing exposure to ionizing radiation.

Methods

A literature search of PubMed,® MEDLINE,® and the Cochrane Database from 1966 to August 2011 was conducted using the MESH search terms pediatrics, children, traumatic brain injury, head injury, concussion, and biomarkers. Other terms also searched included biochemical markers, neuronal/glial/axonal injury, traumatic intracranial lesions, and expansions of these terms to match synonyms, subterms, or derivatives. These terms were searched in all fields of publication (e.g., title, abstract, and key word). The search was limited to the English language articles, “human” studies, and studies that included subjects aged 18 years or younger. Articles without TBI and biomarkers as a primary focus or as a main objective were excluded. In addition, the bibliographies and reference lists of all articles and all review articles were evaluated for other potentially relevant articles. Acceptable study designs included experimental studies, observational studies, and case control studies. Review articles, opinion articles, and editorials were excluded. The abstracts of the publications were screened for relevance and in case of uncertainty regarding the inclusion, the entire text of the article was read.

Studies were defined as prospective or retrospective according to whether the method of data collection and the end-points were defined before patient enrollment began. The full texts of the articles were then pooled and reviewed by two different authors to identify articles that met inclusion criteria. Once the relevant articles were selected, they were reviewed using a standard review form. The review forms allowed the reviewers to objectively assess the content of each article in a consistent fashion. A composite evidentiary table was then constructed. The evidentiary table included the internal identification number, design type, study methods, focus of the article, sample size, TBI severity, biofluid source, collection schedule, clinical variables assessed, outcome measures, results, and conclusions.

Results

The search initially identified 167 articles. Sixty-seven publications were then selected on the basis of the title and abstract screening. Inclusion criteria were applied to the full text of 65 articles. Of these, 49 met inclusion and exclusion criteria and were critically reviewed by five investigators (MR, JK, SB, AP, LP) using a standard review form. There were no randomized clinical control studies identified. All of the included studies were observational cohort studies; 42 (86%) were prospective and 7 (14%) were retrospective. Ninety percent of the studies were published either in or after the year 2000. The mean (standard deviation–SD) sample size of the selected studies was 74 (SD±64, range 6–388) and the median sample size was 58 (interquartile range 31–101). More than 74% of the included studies had fewer than 100 patients.

The majority of the articles—36/49 (73%)—exclusively studied children, and 13/49 (27%) included both children and adults in different proportions.

Evidentiary Table 1 describes the biomarker studies that included both children and adults using either the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or serum/plasma (Table 1). Of the articles that only studied children 18 or younger, 10 (28%) sampled biomarkers solely from CSF, 24 (66%) sampled biomarkers in serum or plasma, and 2 (6%) studies sampled both CSF and serum. Only one study included an analysis of biomarkers in urine. Evidentiary Table 2 describes the biomarker studies that included only children and sampled just CSF (Table 2). Moreover, Evidentiary Table 3 describes the biomarker studies that included only children and sampled serum or plasma or a combination of biofluids (Table 3).

Table 1.

Biomarker Studies that Included Both Adults and Children Under the Age of 18 Years

| Year/author | Sample size | Design | Ages (years) | Severity | Biomarker | Collection times | Type of biofluid | Outcome measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies primarily measuring biomarkers in serum | |||||||||

| 1999 Ingebrigtsen et al.27 | 50 | Prospective Observational | 10–72 | GCS 13–15 and normal CT | S100B | Admission (1–7.5 h post-injury) and hourly until 12 h post-injury | Serum | - MRI within 48 h - Neuropsychological testing within 48 h and at 3 months |

14 (28%) had detectable levels of S100B (mean peak 0.4 μg/L SD±0.3) highest immediately after trauma and declining each subsequent hour. MRI showed contusion in 5 patients, and S100B was detectable in 4/5. There was a trend toward impaired neuropsychological testing at baseline and at 3 months in those with detectable S100B, particularly visual memory and processing speed. The S100B positive group improved more than the S100B negative group. |

| 2000 Romner et al.28 | 388 (278 TBI an– 110 controls) | Prospective Observational | 1–84 | GCS 3–8=severe: GCS 9–13=moderate; GCS 14–15=mild and requiring a head CT | S100B | Single level within 24 h of injury (average 3.8 l) | Serum | - GCS - Intracranial Lesion on head CT |

All controls had undetectable serum levels of S-100. Serum S-100 was detected in all severe TBI patients (mean, 3.6 μg/L; range, 1.2–12.5 μg/L); in 75% of moderate TBI (mean, 0.7 μg/L; range, 0.2–2.2 μg/L) and in 35% in mild TBI (mean, 0.6 μg/L; range, 0.2–6.2 μg/L). 23/25 (92%) with intracranial lesions had detectable levels (mean 2.2; range, 0.2–12.5 μg/L). The sensitivity and specificity for detecting intracranial pathology was 92% and 66%. |

| 2000 Tenedieva et al.29 | 32 | Prospective Observational | 11–55 | GCS <8 | NSE, TNFα, S100B, TSH, TBG, T3, T4, Cortisol, Prolactin | Multiple levels but schedule not specified | Serum | - GOS over 30 days - Coma - Lesion types on CT |

All patients had increased levels of NSE, S-100, and TNFα. TNFα levels normalized 3 days before coma emergence. NSE and S-100 levels normalized 1–2 days and 17 days after emergence, respectively. In comatose patients with DAI TSH, TBG, T3, and cortisol decreased significantly the day before emergence and increased significantly the day after. T3 was the only hormone that was significantly correlated with NSE, TNFα, and S-100. |

| 2002 Murshid and Gader30 | 37 (17 TBI and 20 age- matched controls) | Prospective Observational | 10–40 | GCS ≤12 | Thrombin-Antithrombin (TAT), D-dimer, PT/PTT, thrombin time (TT), Factor VII, Antithrombin III (ATIII), protein C&S Fibrinogen | First level on arrival and daily for 3 days | Serum | - Source (location) of sample: (1) arterial, (2) internal jugular vein, and (3) peripheral venous - GOS at 6 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) |

TAT, F1, and F2 were higher in the jugular than arterial or peripheral in first 24 h but were higher than controls at all time points from all sources. D-dimer concentrations from the 3 sources were significantly higher in TBI than controls. PT was prolonged from all sources for first 2 days. No difference in ATIII, protein S or C by location; significant elevations only on day 3 and 4. Fibrinogen was initially lower in the jugular but then equalized and increased in each source over 4 days. None of the factors were predictive of 6 month outcome. |

| 2004 Vos et al.31 | 85 | Prospective Observational | 15–81 | GCS ≤8 | GFAP, S100B, NSE | Single level at hospital admission | Serum | - GOS at 6 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) - Injury Severity Score (ISS) - Trauma Coma Databank CT criteria - Mortality |

The median serum levels of S100B, GFAP, and NSE were raised compared with normal reference values. S100B, GFAP, and NSE serum levels correlated significantly with the ISS and CT findings but not with age, sex, or GCS. S100B, GFAP, and NSE levels were significantly higher in patients who died or had a poor outcome at 6 months. The area under the curve for predicting poor outcome at 6 months (GOS) was 79.4 for GFAP, 67.7 for S100B, and 78.2 for NSE. Sensitivity and specificity for predicting poor outcome at 6 months was 080 and 0.59 for GFAP; 0.88 and 0.43 for S100B; and 0.80 and 0.55 for NSE. |

| 2006 Bayir et al.32 | 62 | Prospective Observational | 2–73 | GCS 3–13 and isolated head trauma | Platelets, D-dimer, PT, PTT, fibrin, fibrin degradation products (FDP), fibrinogen | Single level at ED evaluation and within 3 hours of injury | Serum | - GCS - CT scan findings (divided into 5 categories: brain edema, linear fracture, depressed fracture, contusion, and hemorrhage) - Mortality |

The mean platelet count, PT, PTT, fibrinogen, FDP, and D-dimer were 153,000 (±37,000 103sub/mL), 2.14 (±0.6 sec), 73 (±2 7sec), 178 (±43 mg/dL), 20 mg/mL, and >1 mg/mL. In patients with GCS ≤8, mean platelet count, PT, PTT, fibrinogen, FDP, and D-dimer levels were 98,000 (±24,000 103sub/mL), 2.7 (±0.5 sec), 89 (±12 sec), 128 (±33 mg/dL), >20 mg/mL, and >1 mg/mL, respectively. There was a significant negative relationship between GCS and PT, PTT, FDP and D-dimer levels. There was a positive relationship between GCS and fibrinogen levels but no relationship with platelets. Mortality was most strongly related to GCS, PT, FDP, and D-dimer levels. Mortality was significantly correlated with GCS, PT, FDP, and D-dimer. There was no relationship between mortality and CT findings and no relationship with platelets, PTT, and fibrinogen levels. |

| 2006 Bazarian et al.33 | 35 | Prospective Observational | 10–83 | GCS 13–15 | S100B, C-Tau | Single level within 6 h post-injury | Serum | - Rivermead Post Concussion Questionnaire (RPCQ) scores at 3 months - Post-concussive syndrome (PCS) at 3 months |

The mean RPCQ score for the group was 13.0 (SD 13.6). 16/31 (47.5%) had PCS. The mean S100B level was 0.35±0.79μg/L. The mean C-tau level was 4.85±9.23 ng/mL. There was no statistically significant correlation between 3-month total RPSQ scores and marker levels (S100B: r=0.071, C-tau: r=0.22). There was no statistically significant correlation between PCS and marker levels (S100B: AUC=0.59 [95% CI=0.038–0.80]; C-tau: AUC=0.63 [95% CI=0.43–0.84]). Using any detectable level as the cutoff between normal and abnormal serum levels, the sensitivity of S100B and C-tau for 3-month PCS ranged from 43.8–56.3% and the specificity from 35.7–71.4%. |

| 2008 Nylen et al.34 | 59 | Prospective Observational | 8–81 | GCS ≤8, ICP monitor and on a ventilator | S100B, S100A1B, S100BB | Initial level as soon as possible (within 2 days) then post-admission on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and once between days 11–14 | Serum | - GOS at 12 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) - Marshall Classification - ICP - Multiple trauma vs. “isolated” TBI |

Maximum serum S100B, S100A1B, and S100BB were increased in almost all patients. They followed the same temporal course, with early peak concentration on day 1, then rapidly decreasing over 2 days. S100B had the highest values, followed by S100A1B then S100BB. Patients with an unfavorable outcome had increased max levels of all 3 markers. Cutoff values for 100% specificity for unfavorable outcome was 0.55 μg/L (S100B), 0.30 μg/L (S100A1B), and 0.17 μg/L (S100BB). AUC for S100A1B=0.71 (95% CI 0.57–0.85), for S100BB=0.72 (95% CI 0.57–0.86) and for S100B=0.69 (95% CI 0.54–0.83). Max levels in all 3 were increased in those with a midline shift of >5 mm on the first CT. ICP correlated with max levels. Max levels were not significantly increased in multiple trauma compared with “isolated” TBI. |

| 2009 Morochovic et al.35 | 102 | Prospective Observational | 12–84 | GCS 13–15 | S100B | Single level within 6 h of injury | Serum | - Abnormalities on CT - Alcohol concentration - Time to blood draw |

Levels of S100B in patients with GCS 13, 14, and 15 were 0.26 (SD±0.34), 0.43 (SD±0.56), and 0.85 (SD±3.11) ng/mL, respectively. Sensitivity of serum S100B assay for detecting abnormalities on CT was 83.3% (95% CI 0.58–0.96), specificity 29.8% (95% CI 0.21–0.41), positive predictive value 20.3% (95% CI 0.12–0.32), and negative predictive value 89.3% (95% CI 0.71–0.97). Three patients with abnormal CT had negative levels of S100B, two of whom needed surgical treatment. Median ISS in S100B negative group was lower than in S100B positive group (1 [1.0–3.0] vs. 1 [1.0 to 10.0]). There was a significant association between S100B and ISS (r=0.44, 95% CI 0.26–0.58). There was no correlation between S100B and alcohol concentration (r=−0.15) or time from injury to drawing blood (r=−0.11). |

| Studies primarily measuring biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid | |||||||||

| 1998 Stahel et al.36 | 25 (10 TBI and 15 controls) | Prospective Observational | 16–59 | GCS ≤8 and abnormal CT | IL-12 | Once daily over 14 days | CSF, Serum | - TBI vs. control - BBB Function (CSF/serum albumin ratio–QIL-12) |

In controls, overall mean IL-12 CSF level was 0.57 (SD±0.39; range 0.4–1.7 pg/mL). In TBI patients, overall mean CSF level was 30.94 (SD±0.45.94; range 0.4–321.5 pg/mL). In the TBI group, 3 patients had evidence of BBB leakage over 14 days, 4 patients had leakage over 7 days, and 3 had no evidence of leakage. |

| 1996 Kossmann et al.37 | 25 (22 TBI and 3 LP or VP shunt controls) | Prospective Observational | 17–73 | GCS ≤8 and abnormal CT | IL-6, NGF | Every 3 days (routine drainage) and when ICP>15 mmHg over 22 days | CSF | -TBI vs. control - Correlation between the 2 markers - GOS at 3 months |

Little or no IL-6 and NGF were detected in control patients. IL- was detected in all TBI patients and peaked at 7 days. Maximal levels 140 to 35,500 pg/mL. NGF was always detectable in the 5 non-survivors (GOS=1). In those with moderate outcome (GOS=2–3), 3/8 had no detectable NGF. In those with good outcome (GOS=4–5), 5/9 had no NGF. Those with NGF had higher levels of IL-6. |

| 2004 Hayakata et al.38 | 30 (23 TBI and 7 lumbar puncture controls) | Prospective Observational | 14–68 | GCS ≤8 | S100B, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10 | First level at intraventricular catheter insertion, then levels at 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h | CSF, Serum collected but not reported | - TBI vs. control - GCS at admission - Correlation with ICP - GOS at 6 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) |

Mean peak CSF concentrations of all the markers were significantly higher in TBI patients than controls. For both S100B and IL-1β, there was a positive correlation between peak CSF levels and ICP at each time point: r2= 0.73 and 0.26, respectively. Both S100B and IL-1β were significantly higher in the high-ICP group than in the low-ICP group. There was no correlation between any of the markers and GCS score. Only CSF S100B concentrations were correlated with mass volume r2=0.316. Elevated CSF S100B levels were significantly associated with unfavorable GOS outcome. There was a trend for IL-1β. |

| 2006 Uzan et al.39 | 28 (14 pts, 14 controls) | Prospective Observational | 5–69 | GCS ≤8 | sFas, caspase-3, bcl-2 | Levels at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10 days post-injury | CSF | - TBI vs. control - ICP, CCP (cerebral perfusion pressure) - Injury severity on initial CT head scan using Marshall classification - GOS at hospital discharge |

sFas, caspase-3, and bcl-2 were not found in the CSF of controls, but levels were significantly elevated in TBI patients at all time points post-injury. Caspase-3 significantly correlated with ICP and CPP. The highest peak of sFas occurred on day 5 post-injury (173.64±15.7 ng/mL). The mean highest caspase-3 level occurred on day 5 (3.8±1.3 μM/min). The mean highest bcl-2 levels occurred on day 3 (119±28.5 ng/mL). |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TBI, traumatic brain injury; NSE, neuron specific enolase; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; TBG, thyroxine-binding globulin; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; DAI, diffuse axonal injury; PT/PTT, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time; F1, F2, prothrombin fractions 1 and 2; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; ISS, Injury Severity Score; ED, emergency department; SD, standard deviation; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; ICP, intracranial pressure; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IL, interleukin; BBB, blood-brain barrier; NGF, nerve growth factor.

Table 2.

Biomarker Studies that only Included Children Under the Age of 18 Years and Sampled Cerebrospinal Fluid

| Year/author | Sample size | Design | Ages (years) | Severity | Biomarker | Collection times | Type of biofluid | Outcome measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 Whalen et al.40 | 43 (14 TBI and 9 bacterial meningitis controls and 20 normal lumbar puncture controls) | Prospective Observational | 0.2–16 | GCS <8 and abnormal CT | E-selectin, P-selectin, L-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 | At 3 Intervals: <12, 12–24, 24–48 h | CSF | - TBI vs. 2 controls | P-selectin was significantly increased in TBI (12.8 [9.5–104.8] ng/mL) vs. normal controls but not vs. meningitis. ICAM-1 was significantly increased in meningitis (82.8 [48.5–195.3]) vs. both TBI (35.4 [28.9–217.4]) and control. Levels of ICAM-1 in TBI were quite variable. E-selectin was significantly increased in meningitis (32.2 [19.0–79.0] ng/mL) vs. TBI (17.2 [7.8–56.1] ng/mL) and control. L-selectin was increased in meningitis (373.4 [101.1–955.2] ng/mL) vs. TBI (57.7 [0–755.5] ng/mL) and control. VCAM-1 was increased in meningitis (200.0 [37.8–739.2] ng/mL) vs. TBI (8.4 [0–388.9] ng/mL). ICAM-1 was strongly associated with child abuse. |

| 2000 Whalen et al.41 | 58 (27 TBI and 7 bacterial meningitis controls and 24 normal lumbar puncture controls) | Prospective Observational | 0.1–16 | GCS ≤8 and abnormal CT | IL-8 | Within 12 h of injury and every 12 h until catheter removed | CSF | - TBI vs. 2 controls - Mortality |

IL-8 is markedly increased in children with severe TBI. IL-8 was increased in CSF in children with TBI (0–12 h) (4452.5 [0–20,000] pg/mL) vs. control (14.5 [0–250] pg/mL). IL-8 in CSF from patients with meningitis (5,300 [1510–22,000] pg/mL) was also significantly higher than controls but was not different from children with TBI. High concentrations of CSF IL-8 correlate with mortality. |

| 2004 Shore et al.42 | 19 | Prospective Observational | Infancy to adolescence | GCS ≤8 | NSE, S100B, IL-6, VEGF | First level at intraventricular catheter insertion then levels daily | CSF | - Continuous vs. intermittent CSF drainage - Drainage volume - ICP, MAP and CPP - GOS at 6 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) |

Intermittent drainage (ID) was associated with significantly higher mean CSF concentrations of NSE, S100B, IL-6, and VEGF and significantly lower volumes than continuous drainage (CD). Mean NSE levels were 85.89±10.62ng/mL in CD vs. 143.75±13.45 ng/mL in ID. Mean S100B levels were 1.45±0.17 ng/mL (CD) vs. 2.10±0.23 (ID), respectively. Mean IL-6 levels were 463.54±66.04 ng/mL (CD) vs. 663.85 ng/mL±87.54 ng/mL (ID), respectively. Mean VEGF levels were 25.89±1.71 ng/mL (CD) vs. 42.98±6.87ng/mL (ID), respectively. CD had significantly lower mean ICP, MAP, and CPP than ID. There was no significant difference in GOS score between drainage methods. |

| 2005 Satchell et al.43 | 86 (67 TBI and 19 normal lumbar puncture controls) | Retrospective Observational | 0.1–16 | GCS 3–15 requiring an ICP monitor | Cytochrome c, Fas, Fas-L, Caspase-1, Caspase-3, pro-IL-1β, IL-1β | Samples taken from 0–10 days post-injury but schedule not specified | CSF | - TBI vs. controls - Inflicted (iTBI) vs. non-inflicted (nTBI) - GCS (dichotomized as GCS ≥5 vs. GCS <5) - Age (dichotomized into <4 vs. ≥4 years old) - Survival |

Cytochrome c was not different in TBI vs. controls but it was significantly increased in iTBI vs. nTBI (2.10 [0.07–63.82] vs. 0.62 [0.30 to 26.22] ng/mL, respectively). Cytocrome c was significantly increased in females vs. males after TBI (1.63 [0.30–63.82] vs. 0.61 [0.07–26.22] ng/mL, respectively) and in TBI with GCS ≥5 vs. GCS <5 (1.51 [0.07–21.59] vs. 0.67 [0.30–63.82] ng/mL, respectively). Fas, caspase-1, and IL-1β were significantly increased in all TBI vs. controls. Pro-IL-1β was significantly decreased in all TBI vs. controls. Fas-L and caspase-3 levels were not different between TBI and controls. Fas was significantly increased in iTBI vs. nTBI (0.93 [0.26–2.26] vs. 0.40 [0.0–2.73] U/mL, respectively). Caspase-1 was significantly increased in TBI age <4 yrs vs. ≥4 yrs (21.28 [5.96–483.31] vs. 9.37 [2.80–190.30] pg/mL, respectively). |

| 2006 Cousar et al.44 | 55 (48 TBI and 7 controls) | Prospective Observational | 0.1–16 | GCS 3–15 necessitating ICP monitoring | Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) | Initial level within 24 h, then another level after 24 h | CSF | - TBI vs. control - Age (dichotomized into <4 vs. ≥4 years old) - GOS at 6 months |

Increased HO-1 was significantly higher in TBI vs. control patients–mean 2.75±0.63, peak 4.17±0.96 ng/mL vs. control (<0.078 ng/mL, not detectable). Increased HO-1 levels were significantly associated with increased injury severity and unfavorable neurological outcome. Increased HO-1 concentration was independently associated with younger age. HO-1 increases after TBI; after injury. it appears to be more prominent in infants when compared with older children. |

| 2006 Lai et al.45 | 41 (34 infants and children and 7 normal lumbar puncture controls) | Prospective Observational | 0.2–16 | GCS 3–15 necessitating ICP monitoring | HSP60 | Initial level within 24 h, then another level after 24 h (range of 3–134 h post-admission) | CSF | - TBI vs. control - Age (dichotomized into <4 vs. ≥4 years old) - GCS at admission - Accidental vs. inflicted injury - GOS at 6 months |

Peak CSF HSP60 concentration was significantly increased in TBI patients vs. controls 0.84 ng/mL (range 0–44.59) vs. 0.0 ng/mL (range 0–0.48), respectively. Induction of HSP60 occurred early after the injury. Peak HSP60 concentration was independently associated with the admission GCS score. Age, mechanism of injury (accidental vs. inflicted TBI), sex, survival status, and neurological outcome (6-month GOS) were not associated with CSF HSP60 levels. |

| 2007 Shore et al.46 | 108 (88 TBI and 20 non-injured lumbar puncture controls) | Retrospective Observational | Mean age 6.6 | GCS ≤8 with abnormal CT | S100B, NSE | Single level within 24 h of injury | CSF | - TBI vs. control - Age (dichotomized into <4 vs. ≥4 years old) - GCS at admission - Inflicted TBI (iTBI) vs. non-inflicted TBI (nTBI) - GOS at 6 months |

Significant differences in NSE and S100B between TBI and controls. NSE was 69.5±SEM 6.6 ng/mL in TBI vs. 6.92±2.0 ng/mL in controls. S100B was 2.82±0.18 ng/mL in TBI vs. 0.04±0.009 ng/mL in controls. There was no difference between iTBI and nTBI for NSE or for S100B. There was a correlation between S100B and NSE levels across patients (r=0.614). There was a significant inverse correlation between GCS and NSE (r=−0.49) and S100B (r=−0.49) with controls treated as GCS 15. There was a significant inverse correlation between GOS and NSE (r=−0.335) and S100B (r=−0.386). In children ≤4 yrs, neither GCS nor GOS correlated with NSE or S100B. |

| 2008 Chiaretti et al.47 | 60 (29 TBI and 31 lumbar puncture controls) | Prospective Observational | 1–16 | GCS ≤8 with isolated head trauma | IL-6, NGF | Initial level at 2 h, then at 48 h post-injury | CSF | - TBI vs. control - GOS at 6 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) - GCS |

NGF and IL-6 were significantly higher by 10 and 23-fold in TBI than controls at 2 h post-injury. NGF increased significantly from 2 to 48 h but IL-6 declined. Correlation between NGF and IL-6 at 2 h was 0.47 and at 48 h, it was 0.72. At 2 h post-injury, NGF inversely correlated with GCS score (−0.71) but IL-6 did not (−0.31). Two hour levels of NGF were significantly lower in patients with better outcome but not IL-6. However, at 48 h post-injury, NGF and IL-6 were significantly higher in those with good outcome. |

| 2008 Chiaretti et al.48 | 48 (27 TBI and 21 lumbar puncture controls) | Prospective Observational | 1–16 | GCS ≤8 with isolated head trauma | IL-1β, IL-6, NGF, BDNF, GDNF | Initial level at 2 h, then at 48 h post-injury | CSF | - TBI vs. control - GOS at 6 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) - GCS |

NGF and IL-6 were significantly higher by 10 and 23-fold in TBI than controls at 2 h post-injury. NGF and IL-1β increased from 2 to 48 h whereas BDNF, GDNF, and IL-6 decreased. Smaller but significant differences were also found for BDNF and IL-1β but no difference for GDNF. NGF and IL-1β correlated significantly with GCS score but IL-6, BDNF, and GDNF did not. Levels of NGF at 2 h were significantly lower in patients with better outcome. Patients with better outcome had smaller increases in IL-1β but significantly stronger NGF and IL-6 up-regulation. |

| 2009 Chiaretti et al.49 | 64 (32 TBI and 32 matched lumbar puncture controls) | Prospective Observational | 1–16 | GCS ≤8 admitted to the PICU within 4 h of injury | NGF, BDNF, GDNF, NSE, DCX | Initial level at 2 h after admission, then at 48 h after admission | CSF | - TBI vs. control - GCS - GOS at 6 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) |

Levels of NGF, NSE, and DCX at 2 h were significantly increased in TBI compared with controls (NGF: 406.44±23.12 vs.18.13±2.14); (NSE: 90.84±7.12 vs. 2.12±0.3); (DCX: 0.87±0.1 vs.0.1); and (BDNF: 31.16±3.32 vs. 6.44±1.55). There was no difference for GDNF. NGF, NSE, and DCX levels increased further in TBI patients at 48 h, whereas BDNF and GDNF levels decreased. Levels of NGF, DCX, and NSE at 2 h correlated significantly with GCS scores (−0.83, −0.70, and −0.90). There was no correlation for BDNF and GDNF. NGF, DCX, and NSE levels at 2 h were significantly lower in patients with better neurologic outcomes. Patients with better neurologic outcomes had NSE levels that decreased over 48 h, whereas NGF and DCX were upregulated and increased significantly. |

TBI, traumatic brain injury; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; CT, computed tomography; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule, CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IL, interleukin; NSE, neuron specific enolase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; ICP, intracranial pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; NGF, nerve growth factor; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; GDNF, glial-derived neurotrophic factor; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; DCX, doublecortin.

Table 3.

Biomarker Studies that only Included Children Under the Age of 18 Years and Sampled Serum/Plasma/Urine or a Combination

| Year/author | Sample size | Design | Ages (years) | Severity | Biomarker | Collection times | Type of biofluid | Outcome measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 Takahashi et al.50 | 152 | Prospective Observational | 0–19 | No GCS; 7 groups based on CT findings | Aldosterone, CK-BB | Within 4 h post-injury | Serum | - History and CT findings (1) simple head injury; (2) skull fracture only; (3) cerebral contusion/ negative CT; (4) EDH; (5) SDH; 6) cerebral contusion by CT; (7) cerebral contusion and EDH or SDH. - Dichotomized GOS score |

Aldosterone concentrations were undetectable in group 1, low in groups 2, 3. Levels were highest in group 4 at 254.2 (SD±22.4) pg/mL and in group 7 at 238.0 (SD±27.4). CK-BB was undetectable in groups 1, 2, 3 and elevated in groups 4–7 with the highest levels in group 7 at 16.24 (SD±3.71) IU/L and group 5 at 13.2 (SD±5.47). 73% of patients with a poor GOS score had elevated aldosterone and elevated CK-BB levels. |

| 2000 Ben Abraham et al.51 | 61 | Retrospective | 0–15 | Isolated EDH | Arterial blood gas, glucose, electrolytes (K+, Na+), hemoglobin, and coagulation studies | Admission | Serum | - Modified GOS at discharge - “Good recovery”=resume normal life despite minor deficits - “Moderate disability”=capable of functioning independently - “Severe disability”=dependent in activities of daily life - “death” |

ABG was abnormal in 19 (31.3%) patients, hypokalemia (<3.5 mEq/L) in 33 (65.9%), hypocalcemia (<8.5 mg%) in 11 (22%), alkalemia in 18.8%, and acidemia in 12.5%. Hyperglycemia was significant. Glucose levels ranged from 70–578 mg%, with levels above 120 mg% in 37 (84.1%) patients, above 180 mg% in 21 (47.7%), and above 270 mg% in 7 (15.9%). All the patients in whom diabetes insipidus developed died. Anemia (Hg<10 g%) was found in 32 (58.3%), and coagulation studies (PT, PTT, and INR) were abnormal in 10 (16.4%), 7 (11.5%), and 6 (9.8%) patients, respectively. Hyperglycemia and hypokalemia were associated with poor outcome. |

| 2000 Fridriksson et al.52 | 50 | Prospective Observational | 0–18 | GCS 3–5 necessitating a head CT | NSE | Single level within 24 h of injury (average 4 h) | Serum | - GCS - Intracranial lesion on head CT |

22 (45%) had positive intracranial lesions on head CT. Overall NSE levels ranged from 4.3 to >100 ng/mL, and 63% of the patients had levels ≥15 ng/mL. Mean level were significantly higher when GCS <12 (36.6 ng/mL) compared with GCS <12 (18.4 ng/mL). Mean NSE level were not significantly different in the positive CT group 26.7 (±21.4) ng/mL vs. the negative CT group 17.8 (±7.8) ng/mL. Levels ≥15.3 ng/mL yielded the highest sensitivity and specificity for predicting intracranial injury on the ROC curve. |

| 2002 Berger et al.53 | 61 (45 TBI and 16 orthopedic controls) | Prospective Observational | <13 | GCS 3–8=severe: GCS 9–12=moderate; GCS 13–15=mild and necessitating a head CT | S100B | First level within 24 h of injury (average of 5.5 h in severe/2.9 h in mild and mod), and every 12 h for 5 days | Serum | - TBI vs. control - Marshall CT Classification modified from 6 to 3 categories: (a) normal; (b) diffuse injury (with or without shift); (c) mass lesions (evacuated and nonevacuated) |

22/45 TBI patients had abnormal (+ve) S100B levels. 6/12 severe TBI were +ve for S100B; 4/6 moderate TBI were +ve for S100B and 12/27 mild TBI +ve s100B levels. There was no relationship between S100B and lesions on CT. First samples had the highest concentrations. Beyond 12 h, S100B was only abnormal in severe TBI. S100B had a minimal negative correlation with GCS score. |

| 2003 Akhtar et al.54 | 17 | Prospective Observational | 5–18 | GCS ≤14 with a negative CT | S100B | First level within 6 h of injury, then at 12 h | Serum | - Findings on MRI within 96 h of injury - Isolated TBI vs. TBI with other injuries |

7/17 (41%) had a positive MRI. In those with positive MRI, mean S100B within 6 h was 0.53 μg/L (95% CI, 0.25–0.81) and at 12 h it was 0.35 μg/L (95% CI, 0.24–0.47). In those with negative MRI S100B within 6 h was 0.39 μg/L (95% CI, 0.13–0.65) and at 12 h was 0.24 μg/L (95% CI, 0.13–0.36). There was no statistical significance between the two groups at either time point. Levels of S100B were significantly higher at each time point in patients with head and other body injury compared with isolated head injury. |

| 2003 Spinella et al.55 | 163 (27 TBI and 136 healthy controls) | Prospective Observational | <18 | Traumatic intracranial lesion on CT or MRI | S100B | Single level within 12 h of injury (average 7.7 h) | Serum | - GCS at presentation - PRISM 24 (Pediatric Risk of Mortality score) at 24 h - PCPC (Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category) score at hospital discharge and 6 months post-injury and/or death. Good was ≤3 vs. poor was ≥4. |

S100B levels in healthy children was 0.3 μg/L (90% CI, 0.03–1.47) and inversely correlated with age. In TBI, S100B levels of ≥2.0 μg/L were associated with poor outcome with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 95%. The area under the ROC curve for S100B was 0.94. The area under the curve for predicting poor outcome was 0.99 for the PRISM 24 and 0.83 for the GCS score. |

| 2005 Bandyopadhyay et al.56 | 86 | Retrospective Observational | 0.9–18 | GCS 3–15 isolated non-penetrating TBI necessitating CT Scan | NSE | Single level at ED evaluation and within 24 h of injury (average 3.8 h) | Serum | - GOS at hospital discharge assigned retrospectively (dichotomized into good recovery GOS=5 vs. poor GOS <5) - Abnormal CT - GCS (dichotomized into GCS=15 vs. GCS <15) |

The mean NSE level was significantly higher in those with poor outcome (46.4±SD12.7 ng/mL) than those with good outcome (19.5±SD1.4 ng/mL). Mean levels were significantly higher in those with abnormal CT scan (26.9±SEM 3.0) than normal CT (16.8±SEM1.1). Also, levels were significantly elevated in those with GCS <15 (31.1±SEM 3.6) than GCS=15 (16.7±SEM 1.2). The area under the ROC curve was 0.83 for discriminating poor vs. good outcome. At a cutoff value of 21.2 ng/mL, NSE was 86% sensitive and 74% specific in predicting poor outcome. The area under the ROC curve was 0.66 for predicting abnormal CT. |

| 2005 Berger et al.57 | 164 (56 nTBI, 44 iTBI), and (44 healthy controls, 20 fracture controls) | Prospective Observational | <13 | GCS 3–15 with clinical diagnosis of TBI necessitating admission and a CT within 24 h of injury | S100B, NSE, MBP | Initial level within 12 h of injury and another within 12–24 h. Severe TBIs had daily levels for 5 days | Serum | - TBI vs. controls - Controls with and without extracranial injuries - iTBI) vs. nTBI - GCS |

No difference in median NSE, S100B, or MBP levels between healthy controls and fracture controls. The initial median NSE levels were significantly higher in TBI than controls (24.29 ng/mL vs. 0.15 ng/mL). The initial median S100B levels were significantly higher in TBI than controls (0.026 ng/mL vs. 0.016 ng/mL). No difference was found in MBP levels in TBI compared with controls. For NSE, S100B, and MBP, there was no difference between nTBI and iTBI and no association with GCS. The AUC for initial NSE levels to predict TBI was 0.85 with 71% sensitivity and 64% specificity (at 11.36 ng/mL). The AUC for initial S100B levels to predict TBI was 0.82 with 77% sensitivity and 72% specificity (at 0.017 ng/mL). |

| 2006 Berger et al.58 | 127 (27 hypoxic-ischemic brain injury [HIBI] and 56 nTBI, 44 iTBI) | Prospective Observational | <17 | GCS 3–15 with hypoxic-ischemic brain injury or TBI necessitating admission | S100B, NSE, MBP | Initial level as soon as possible and then every 12 h for 5 days | Serum | - Difference between groups ([HIBI]; nTBI; iTBI) - Time to peak concentrations |

The mean peak NSE level did not differ by group (27.8±SEM 33.1 vs.36.2±34.7 vs. 40.2±23.6 ng/mL for HIBI vs. iTBI vs. nTBI). The mean peak S100B levels didn't differ (0.06±0.17 vs. 0.08±0.17 vs. 0.08±0.10 ng/mL for HIBI vs. iTBI vs. nTBI). Peak MBP also showed no difference (0.26±1.66 vs. 1.27±5.29 vs. 1.55±2.83 ng/mL for HIBI vs. iTBI vs. nTBI). Time to peak NSE level was significantly different in nTBI vs. iTBI (1.7±1.2 vs. 3.1±1.0 h after injury) and HIBI vs. iTBI (2.4±1.3 vs. 3.1±15.0 h). No difference between nTBI and HIBI. For S100B, there were significant differences in time to peak for nTBI vs. HIBI (1.17±1.08 vs. 2.21±1.06) and nTBI vs. iTBI (1.17±1.08 vs. 2.66±1.10). No difference for iTBI vs. HIBI. Time to peak for MBP was significant for nTBI vs. iTBI (1.91±1.46 vs. 3.40±0.81) and iTBI vs. HIBI (3.40±0.81 vs. 1.79±1.04). No difference nTBI and HIBI. |

| 2006 Berger et al.59 | 98 at risk for inflicted TBI (iTBI) | Prospective Observational | <1 | Infants presenting with non-specific neurologic symptoms without a history of trauma | S100B, NSE, MBP | Single level obtained at initial ED presentation as part of routine care | Serum (66%) or CSF (34%) | -Diagnosis of abuse (iTBI) over 1 year | Based on discharge diagnoses and follow-up: 76% (74/98) had no TBI, 14% (14/98) had iTBI, 5% (5/98) were indeterminate, and 5% (9/98) had brain injury not caused by iTBI. For CSF and serum combined an ROC for NSE to identify iTBI had an AUC=0.70 with 69% sensitivity and 70% specificity (at 11.77 ng/mL). A ROC for MBP to identify iTBI had an AUC=0.67 with 36% sensitivity and 100% specificity (at 0.30 ng/mL). S100B was increased in 90% of patient with non-TBI and was not specific for iTBI. ROCs using samples only from patients with all 3 biomarkers (n=60) showed NSE AUC=0.75, MBP AUC=0.62, and S100B AUC=0.45. |

| 2006 Berger and Kochanek60 | 26 (15 brain injury [9 hypoxic, 6 iTBI] and 14 healthy controls) | Prospective Observational | <17 | GCS 3–15 with HIBI or TBI necessitating admission and having IV and urinary catheters | S100B | Initial level as soon as possible and then every 12 h for 3 days | Serum, Urine | - Correlation between urinary and serum levels - brain injury (HIBI and iTBI) vs. control - Time to peak urinary concentration - GCS - GOS at 6 and 12 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) |

Urinary S100B concentrations were detectable in 80% of subjects with increased serum S100B concentrations and 0% of controls. There was a significant correlation between initial urinary and serum S100B. The mean time to peak urine S100B level was 55.3 (SD 29.5) h post-injury. There was no correlation between GCS and GOS or between GCS and initial or peak urinary S100B. Subjects with an undetectable urinary S100B were more likely to have a good outcome (5/5) than those with a detectable urinary S100B (2/10) (sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 100%). Those with a normal serum S100B were also more likely to have a good outcome (4/5) than those with an abnormal serum S100B (1/10). |

| 2006 Braissoulis et al.61 | 36 (9 ARDS, 9 sepsis, 9 TBI, 9 ventilated cancer patients) | Prospective Observational | Mean 7.5 in TBI patients | Severe TBI (GCS not specified) | KL-6 | Levels at 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 days | Plasma | - Relation to C-reactive protein (CRP)- Disease severity as measured by PRISM, TISS (Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System), length of stay (LOS), and length of mechanical ventilation (LOMV) | Patients with ARDS had higher early plasma levels of KL-6 (956±400 U/mL), compared with patients with TBI (169±9 U/mL), sepsis (282±81 U/mL), and ventilated controls (255±40 U/mL). There was no significant difference between KL-6 levels in the early and late samples of all groups. Only in patients with ARDS, plasma KL-6 levels were significantly higher in non-survivors than survivors and correlated positively with LOS (r2=0.7), LOMV (r2=0.8) and TISS (r2=0.75, p<0.03). KL-6 did not correlate with CRP or PRISM. There was no correlation between KL-6 and LOS, LOMV, PRISM, TISS, and CRP values in the other groups. |

| 2007 Beers et al.62 | 30 (15 iTBI and 15 nTBI) | Cross-sectional | 0.3–12 | GCS 3–15 | NSE, S100B, MBP | Initial level as soon as possible and then every 12 h for 5 days | Serum | - iTBI vs. nTBI - Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (VABS) at 6 months - Intelligence Quotient (IQ) at 6 months - GOS at 6 months |

Significant between group differences (iTBI vs. nTBI) were found for time to peak NSE (66.48±53.56 vs. 8.11±11.58), S100B (43.30±51.41 vs. 8.21±8.29), and MBP (77.66±56.77 vs. 21.63±28.39). The iTBI group had worse GOS scores, poorer adaptive abilities. and lower IQ. Time-to-peak comparisons resulted in significant differences for NSE, S100B, and MBP. When all TBIs (iTBI and nTBI) were combined, initial, peak, and TTP NSE were all significantly correlated with 6-month GOS and IQ. NSE Peak and TTP were correlated with VABS. S100B peak correlated to VABS and IQ. Peak MBP was correlated GOS, VABS and IQ. |

| 2007 Berger et al.63 | 152 | Prospective Observational | <13 | GCS 3–8=severe: GCS 9–12=moderate; GCS 13–15=mild and necessitating a head CT | NSE, S100B, MBP | Initial level within 12 h of injury and another within 12–24 h. Severe TBIs had daily levels for 5 days | Serum | - Age (dichotomized into <4 vs. ≥4 years old) - GOS and GOS-Peds over 3 periods (0–3 months; 4–6 months; 7–12 months) |

Higher levels of NSE, S100B, and MBP were associated with worse outcome at all time points. Peak levels were better predictors than initial levels. Correlation between initial and peak NSE was much stronger in children ≤4yrs; there was virtually no correlation in those >4yrs. Initial and peak S100B were correlated with both age groups. Initial MBP was only associated with outcome in ≤4yrs. Initial and peak NSE, S100B, and MBP predicted dichotomized 0–3 month GOS with an accuracy=77%, NPV=97%, and PPV=75%. They predicted 4–6 month GOS with an accuracy=78%, NPV=96%, and PPV=42%. They predicted 7–12 month outcome with an accuracy=78%, NPV=97% and PPV=33%. |

| 2007 Braissoulis et al.64 | 40 (10 ARDS, 10 sepsis, 10 TBI, 10 ventilated cancer patients) | Prospective Observational | Mean age 7.5 in TBI patients | Severe TBI (GCS not specified) | TGF-B1, sICAM-1, sL- and sE-selectins | Initial level on day of PICU admission then on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 post-admission | Plasma | - Relation to CRP - Disease severity as measured by PRISM, TISS, LOS, and LOMV |

The highest values of sICAM-1 were observed in patients with TBI and those of sE-selectin in patients with sepsis. Patients in the control group did not show an elevation of sE-selectin and sICAM-1 levels longitudinally. Significantly increased levels of TGF-β1, sE-selectin, sL-selectin, sICAM-1 were demonstrated among survivors in sepsis and ARDS and were positively correlated with LOS and mechanical ventilation. |

| 2007 Haqqani et al.65 | 6 | Prospective Observational | 1–17 | GCS ≤8 with abnormal CT and on a ventilator | S100B and exploration of brain-originating proteins in serum | Single level within 8 h of injury | Serum | - Clustering patterns and correlation to S100B - GCS |

Serum S100B levels ranged from 1.5–2.7-fold over the reference levels (0.43±0.02 μg/L) in 5/6 patients. Hierarchical clustering identified 3 proteins that had a similar pattern (correlation R >0.8) to S100B (β2-glycoprotein I precursor, neurofilament-triplet H protein, and complement factor H-related protein 5 precursor) and 9 proteins that correlated with GCS (Cdc42 effector protein 1, carboxypeptidase β2 precursor, N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase precursor, lymphoid-restricted membrane protein, prothrombin precursor, renalase precursor, corticosteroid-binding globulin precursor, α2-antiplasmin precursor, α1-antichymotrypsin precursor). |

| 2007 Piazza et al.66 | 15 | Prospective Observational | 1–15 | GCS 3–8=severe: GCS 9–12=moderate; GCS 13–15=mild | S100B | Initial level in the ED and then after 48 hours | Serum | - GCS - GOSE at 6 months - Peripheral injuries |

Nine (9) patients had mild TBI, 2 had moderate TBI, and 4 had severe TBI. Of them, 6/15 had an elevated S100B >0.3 μg/L, (range 0.32–4.15 μg/L). All patients with severe TBI had S100B >0.3 μg/L in the ED and in 3/4 cases, it remained elevated after 48 h. Levels were higher in severe TBI than milder TBI. S100B levels were highest in patients with severe TBI who scored lowest on the ED GCS. Highest levels were from severe TBI cases with concomitant peripheral lesions. All patients had a good 6-month outcome. |

| 2009 Bechtel et al.67 | 152 | Prospective Observational | <18 | GCS 3–15 who needed a head CT | S100B | Single level within 6 h of injury | Serum | - TBI vs. skeletal injury - Intracranial injury (ICI) on CT |

S100B levels were greater in the ICI group (212.9 vs. 84.4 ng/L), in children with long-bone fractures (220 vs. 83.2 ng/L) and in nonwhite children (127.3 vs. 80.5 ng/L). With controlling for time of venipuncture, long-bone fractures, and race, S100B levels were still significantly greater in the ICI group (278 vs. 80.2 ng/L). The ability of S100B levels to detect ICI had an AUC=0.67 (95%CI: 0.55– 0.80). A cutoff 50 ng/L yielded a sensitivity=75%, specificity=56%, PPV=20%, and NPV=90%. When patients with long-bone fractures were excluded, the AUC=0.69, sensitivity=73%, specificity=52%, PPV=23%, and NPV=89%. |

| 2009 Berger et al.68 | 36 (16 TBI and 20 controls) | Retrospective Observational | <18 | GCS 15 who needed a head CT and had a diagnosis of iTBI | 44 different biomarkers (e.g. MMP-9, ICAM, VCAM, eotaxin, 38 cytokines, IL-6, IL-12, TNFR1/2, fibrinogen, HGF, HGF/VEGF, etc…) | Single level as soon as possible (mean sample time was 26 h from injury) | Serum | - TBI vs. 2 controls (nonspecific symptoms in ED nd outpatient surgery) - extracranial vs. no extracranial injury |

21/44 markers were undetectable in most (>50%) cases with no group differences. 14/44 markers were detectable in both cases and controls, but without group difference. 9/44 markers had significant differences between cases and controls. The markers with significant differences between cases and controls were VCAM, IL-12, MMP-9, ICAM, eotaxin, HGF, TNFR2, IL-6, and fibrinogen. Markers higher in TBI were MMP-9, HGF, fibrinogen, and IL-6. Markers higher in controls were ICAM, VCAM, IL-12, eotaxin, and TNFR2. No difference in biomarker concentrations between cases with extracranial injuries. IL-6 and MMP-9 were the most significantly increased after TBI. VCAM and IL-6 had a sensitivity=87% and specificity=90% for distinguishing TBI from controls. |

| 2009 Castellani et al.69 | 109 | Prospective Observational | <18 | GCS 13–15 who needed a head CT | S100B | Single level within 6 h of injury | Serum | - Intracranial lesions on CT - GCS |

Patients with abnormal CTs had significantly higher mean S-100B 0.64μg/L (±SD 0.70; range 0.164–3.22) than those with normal CTs 0.50 μg/L (±SD 0.96; range 0.06–6.66). No significant differences in S100B levels in the pair-wise analysis of GCS groups. The ability of S100B to predict CT outcome showed a sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI: 0.92–1.00), specificity of 0.42 (95% CI: 0.38–0.43), PPV of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.42–0.46) and NPV of 1.00 (95% CI: 0.90–1.00). The ROC curve revealed an AUC of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.58–0.78). Patients with additional injuries had significantly higher mean S-100B 0.79 (±SD 1.09; range 0.08–6.66) than those with no injuries 0.26 (±SD 0.36; range 0.06–2.49). S-100B was the highest in patients with fractures followed by minor injuries in multiple locations, contusion, and polytrauma. |

| 2009 Geyer et al.70 | 148 | Prospective Observational | 0.5–15 | GCS 13–15 with isolated head trauma | NSE, S100B | Single level within 6 h of injury | Serum | - Symptomatic vs. non-symptomatic mild TBI - Correlation between S100B and NSE - Presence of scalp laceration - GCS - Age |

Back-transformed, adjusted S100B means were 0.140 ng/mL (0.083 ng/mL, 0.235 ng/mL) in the asymptomatic group and 0.136 ng/mL (0.061 ng/mL, 0.305 ng/mL) in the symptomatic group. Back-transformed, adjusted NSE means were 28.67 ng/mL (20.97 ng/mL, 39.21 ng/mL) in the asymptomatic group and 31.75 ng/mL (19.61 ng/mL, 51.42 ng/mL) in the symptomatic group. The presence of scalp lacerations had no significant effect on levels of S100B or NSE. There was no significant difference in S100B or NSE between GCS 14 and 15. There was a significant negative correlation between S100B/NSE and age. S100B decreased from 0 to 8 years and then increased. S100B was highest in the 1st year of life. NSE decreased continuously from 0 to 15 years. There was a weak correlation between S100B and NSE (r=0.245). |

| 2010 Berger et al.71 | 100 (28 hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and 72 TBI) | Retrospective Observational | <17 yrs | GCS 3–8=severe: GCS 9–12=moderate; GCS 13–15=mild | NSE, S100B, MBP | Initial level as soon as possible and then every 12 h for 5 days | Serum | - GCS - GOS within 3 months at hospital discharge (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) |

There was a very high specificity for the prediction of poor outcome for subjects classified into high risk trajectories. The specificity was 100% for all 3 biomarkers. These high-risk trajectories were a combination of late, sustained, or increase in biomarkers. For S100B, the 3-group model predicted poor outcome with sensitivity 59% and specificity 100%. For NSE, the 3-group model predicted poor outcome with sensitivity 48% and specificity 98%. For MBP, 3-group model predicted poor outcome with sensitivity 73% and specificity 61%. 17% of subjects with poor outcome were predicted to have good outcome. |

| 2010 Chang and Nager72 | 95 | Prospective Observational | Mean age 6.4 | GCS 3–15 | BNP | Single level drawn on arrival to the ED | Serum | - Intracranial bleed on head CT - GCS - Loss of consciousness - ISS - Hospital and ICU LOS |

BNP levels ranged from 5 pg/mL to 28.8 pg/mL. Mean BNP levels were 5.92 pg/mL in those with an intracranial bleed and 7.28 pg/mL in those with no bleed. BNP levels had a significant negative correlation with the head/neck score of the ISS. There was no association with total ISS, LOC, GCS levels, and hospital and ICU days. |

| 2010 Lo et al.73 | 28 | Prospective Observational | <15 yrs | Isolated accidental TBI and requiring ICU | S100B, NSE, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, L-selectin, SICAM, and endothelin | Single level drawn 24 h post-injury | Serum | - GOS at 6 months (traditional dichotomy into good and poor) | GCS at the time of PICU discharge (DCGCS) had the highest outcome predictive value compared with post-resuscitation GCS (PRGCS), or change in GCS. The motor component of the PRGCS was more predictive value than the whole score. The AUC for predicting poor outcome for each biomarker was 0.92 for L-selectin; 0.88 for IL-8; 0.83 for NSE, S100B, and IL-6. The top 5 prognostic pairs were (1) PRGCS ≤9 and Il-8 >25 pg/mL with AUC=0.98, sensitivity=100%, and specificity=96%; (2) DCGCS ≤13 and IL-8 >20 pg/mL with AUC=0.98, sensitivity=100%, and specificity=96%; (3) DCGCS ≤10 and S100B >0.04 ng/mL with AUC=0.98, sensitivity=100%, and specificity=96%; (4) improved GCS and IL-6 >30 pg/mL with AUC=0.98, sensitivity=100%, and specificity=92%; and (5) DCGCS ≤13 and NSE >12 ng/mL AUC=0.98, sensitivity=100%, and specificity=92%. |

| 2010 Swanson et al.74 | 114 (57 in prospective derivation and 57 in retrospective validation) | Prospective and Retrospective Observational | Mean age 7.1 | GCS 3–15 with suspected TBI and needing a CT | MMP-9, S100B, PT, PTT, D-dimer, CRP | Single level drawn at arrival to the ED | Plasma | - Intracranial lesion on head CT | Plasma levels of D-dimer were associated with brain injury lesions on CT but PT/PTT, CRP, and S100B were not. D-dimer and GCS strongly predicted brain injury on CT, but D-dimer was a stronger independent predictor. A D-dimer level cutoff of 500 pg/μL had an AUC=0.77 and 94% NPV for brain injury on CT. One patient was misclassified. Similar results were found in the retrospective validation and when both cohorts were combined (NPV 94%). In patients with GCS 13–15 and GCS 15, the NPVs were 97% and 96%, respectively, with one misclassified. |

| 2011 Fraser et al.75 | 27 | Prospective Observational (substudy of a hypothermia trial) | 2–17 | GCS ≤8 admitted to the PICU | GFAP | Initial level on day 1, then daily for 10 days post-injury | CSF, Serum | - PCPC scores at 6 months - Full score - 1–2=normal-mild disability - 1–3=normal-moderate disability |

Levels of GFAP were maximal on day 1 post-TBI, with GFAP levels in CSF of 15.5±6.1 ng/mL and in serum of 0.6±0.2 ng/mL. CSF GFAP levels normalized by day 7, whereas serum GFAP decreased gradually to day 10. Serum GFAP on day 1 correlated with 6-month Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category scores (correlation coefficient=0.527) but did not correlate with injury severity or CT on admission. The AUC of GFAP on day 1 for predicting normal to mild outcome was 0.80 (sensitivity 88% and specificity 43% at cutoff=0.6 ng/mL) and for predicting normal to moderate, it was 0.91 (sensitivity 90% and specificity 71% at cutoff=0.6 ng/mL). Serum GFAP levels were similar among children randomized to either therapeutic hypothermia or normothermia. |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; CT, computed tomography; CK-BB, cretine kinase isoenzyme; EDH, epidural hematoma; SDH, subdural hematoma; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; SD, standard deviation; ABG, arterial blood gas; PT, prothrombin time • PTT, partial thromboplastin time; INR, international normalized ratio; NSE, neuron specific enolase; ROC, receiver-operating characteristic; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; SEM, standard error of the mean; MBP, myelin basic protein; AUC, area under the curve; IV, intravenous; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; KL-6, high molecular weight glycoprotein; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; TGF, transforming growth factor; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; IL, interleukin; TNFR, tumor necrosis factor receptor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; BNP, beta natriuretic peptide; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; ISS, Injury Severity Score.

The severity of TBI in these studies ranged from mild to severe: 19 (39%) studies included patients with a GCS score ≤8 (only severe); 18 (37%) included patients with a GCS score of 3–15 (mild to severe); 7 (14%) limited their patients to a GCS score of 13–15 (only mild). There were five studies that used various GCS score cutoffs; two (4%) used a GCS score ≤14; one (2%) used a GCS score <12; and two studies (4%) did not specify the GCS score or the severity.

Outcome was determined at different times post-injury. In-hospital outcome was measured in 26 (53%) studies, 1-month outcome in 1 (2%), 3-month outcome in 4 (8%), 6-month outcome in 15 (31%), and 12-month outcome in 3 (6%) studies. The majority of studies used multiple end-points and outcome measures to assess the biomarkers. Biomarkers were also compared with measures such as age, physiological parameters (intracranial pressure, mean arterial pressure), other biomarkers, and control groups. A summary of the type and the frequency of the different measures used to assess biomarkers is shown in Table 4. The Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), GCS, various non-head injured control groups, and intracranial lesions on CT were used most frequently, with 45%, 37%, 32% and 22% of the studies applying them as end-points or comparators for the biomarkers, respectively.

Table 4.

Description of Type and Frequency of Measures Used To Assess the Biomarkers

| Outcome measures | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Glascow Outcome Scale score | 22 (45) |

| Glascow Coma Scale score | 18 (37) |

| Comparison with a control group | 15 (32) |

| Intracranial lesions on CT | 11 (22) |

| Correlation with another biomarker or correlation with timing of blood draw | 11 (22) |

| Mortality | 7 (14) |

| Inflicted injury/Abusive head trauma | 7 (14) |

| Extracranial injuries | 7 (14) |

| Physiologic parameters (ICP, MAP, CSF drainage) | 6 (12) |

| Age | 5 (10) |

| Marshall classification | 3 (6) |

| Injury Severity Score | 3 (6) |

| Neuropsychological tests/post-concussive syndrome | 3 (6) |

| MRI results | 2 (4) |

| Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category Scale | 2 (4) |

Most studies used multiple outcomes.

ICP, intracranial pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

In 21 (43%) studies, a single sample at a single biofluid time point was obtained for biomarker analysis, while in 28 (57%) studies, multiple biofluid samples were measured over time. Most initial samples were obtained within 24 h of injury, with the earliest being taken within 4 h of injury. There were 99 different biomarkers measured in these 49 studies, and the five most frequently examined biomarkers were S100B (27 studies), neuron-specific enolase (NSE, 15 studies), interleukin (IL)-6 (7 studies), myelin basic protein (6 studies), and IL-8 (6 studies). Other markers, such as nerve growth factor, D-dimer, fibrinogen, IL-1β and L-Selectin, were measured in at least three separate publications and caspase-3, glial cell cerived neurotrophic factor, glial fibrillalry acidic protein, intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, S-ICAM-1, E-Selectin, P-Selectin, matrix metallopeptidase-9, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and tumor necrosis factor-α were examined in two distinct studies.

In addition, we compiled the studies that evaluated the ability of serum biomarkers to determine whether children younger than 18 years old with suspected TBI had intracranial lesions on CT. There were six studies that assessed the relationship between serum markers and CT lesions (Table 5). Two studies found that having NSE serum levels ≥15 ng/mL within 24 h of TBI was associated with the presence of intracranial lesions on CT. There were four studies that assessed serum S100B, but the results were conflicting: Two studies found no association between S100B and intracranial lesions on CT, and the other two studies found a weak association with areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve or 0.66 and 0.68. One study found that low levels of D-dimer were associated with the absence of intracranial lesions.

Table 5.

Association Between Serum Levels of Biomarker and Intracranial Traumatic Lesions on Computed Tomography in Children Younger than 18 Years Old

| Time of sample | Serum marker | Cutoff level | Sensitivity/ specificity | AUC (95% confidence interval) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 Fridriksson et al.52 | 24 | NSE | 15.3 ng/mL | Sensitivity 77% Specificity 52% NPV 74% |

Not provided | |

| 2002 Berger et al.53 | 24 | S100B | Not applicable | No association between S100B and intracranial lesions on CT | Not applicable | No association between S100B and intracranial lesions on CT |

| 2005 Bandyopadhyay et al.56 | 24 | NSE | 15 ng/mL | Not provided | 0.66 | Higher levels of NSE in those with intracranial lesions vs. those without 16.8 ng/mL vs. 26.9 |

| 2009 Bechtel et al.67 | 6 | S100B | 0.05 ng/mL | Sensitivity 75% Specificity 56% PPV 20% NPV 90% |

0.67 (0.55–0.80) | When long bone fractures were excluded: Sensitivity 73% Specificity 52% PPV 23% NPV 89% |

| 2009 Castellani et al.69 | 6 | S100B | 0.16 ng/mL | Sensitivity 100% Specificity 42% PPV 46% NPV 100% |

0.68 (0.58–0.78) |

*CT lesions included isolated skull fractures. Patients with additional injuries had a higher S100B levels |

| 2010 Swanson et al.74 | On arrival to hospital | S100B D-dimer | D-dimer 500 ng/mL | Sensitivity 95% Specificity 42% PPV 36% NPV 96% |

0.77 | No association between S100B and intracranial lesions on CT |

AUC, area under the curve (receiver operating characteristics curve); NPV, negative predictive value; CT,computed tomography; PPV, positive predictive value.

Discussion

This systematic review of the existing literature provides a comprehensive summary of the status of biomarker research in pediatric TBI and demonstrates that validated biomarkers are still lacking. In this review, there are a number of biomarkers that have shown correlation with injury severity measures, global outcome, and neuroimaging abnormalities after TBI. Unfortunately, the studies are difficult to combine and compare because the methodology and reporting between the studies is not uniform. The flurry of research in the area over the last decade is encouraging but is limited by small sample sizes, variable practices in sample collection and processing, inconsistent biomarker-related data elements, and disparate outcome measures. The reporting of the performance characteristics in the studies was variable, with some reporting sensitivity and specificity, others reporting area under the ROC curve, and others simply providing levels without performance measures.

Laboratory and clinical investigators from many different scientific disciplines contribute to the knowledge base of pediatric TBI biomarkers. This diversity of scientific backgrounds is both a strength and an obstacle. The variability in research methods and measures to assess TBI study variables makes it difficult to analyze and compare studies and to draw conclusions that will influence clinical practice.

In 2009, the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke called for a review of the original TBI common data element (CDE) recommendations to ensure they were relevant to pediatric populations. Multidisciplinary work groups composed of pediatric TBI experts were formed (Demographics and Clinical Assessment; Biomarkers; Neuroimaging; and Outcomes Assessment) to offer recommendations for modifications and additions to the original CDEs. The revised CDEs were evaluated at a 2010 workshop and published in 2012.16–20 It will be particularly important for future pediatric biomarker studies to adopt standard practices for sample collection, processing, and storage, and to record biomarker-specific data.17 These recommendations will hopefully help to standardize methodology in future pediatric TBI biomarker studies so the full potential of biomarkers in clinical practice can be realized.

We included studies with both adults and children (defined as younger than 18 years old) for completeness; however, many of these studies did not indicate the proportion of children versus adults evaluated. The performance of the biomarkers in the majority of these studies spanned across ages and did not specifically reflect performance of the biomarker in children. Future studies should either assess these populations separately or provide detailed analyses across age groups.

Serum is the most practical and readily available biofluid and the most clinically useful because CSF is accessible in fewer than 10% of children with TBI. In addition, detecting intracranial lesions on CT, through a blood test, could be used to reduce CT use in children and minimize ionizing radiation exposure that can lead to lethal malignancies.21,22 Of the six studies that we compiled assessing serum markers and CT lesions, two found that having NSE serum levels ≥15 ng/mL within 24 h of TBI was associated with the presence of intracranial lesions on CT. The four other studies that assessed serum S100B had conflicting results: two studies found no association with intracranial lesions and the other two studies found a weak association (area under the curve=0.66 and 0.68). The biomarkers in these studies were unable to satisfactorily detect CT lesions.

Future studies in children will have to consider the limitations of each of the biomarkers being evaluated for CT lesion detection. For example, are the biomarkers being released from other organs or tissues (as with S100B), are adequate control groups being used (multiple trauma), are there lesions that CT is unable to detect (such as diffuse axonal injury), and what about the implications of different lesion types on outcome?

Of note is the fact that biomarkers are being compared with suboptimal measures of severity of injury (GCS) and outcome (GOS). It is difficult to rate the predictive power of serum biomarkers if the clinical measures they are being compared against lack sensitivity and specificity. There are many challenges to consider as we move forward in the clinical application of serum biomarkers.

Our review encompassed all potential biomarkers of TBI, including surrogate markers of traumatic injury, such as those involved in coagulation (D-dimer). We elected to include all potential markers because, in many cases, surrogate markers can be clinically useful in determining injury severity. Although “brain-specific” markers would be ideal for determining the degree of brain injury, many of the putative brain-specific biomarkers have not been studied rigorously enough to prove exclusivity to the brain. In fact, some are released from organs other than the brain during trauma, such as S100B from chondrocytes and adipocytes. Because we cannot yet determine which markers are actually exclusive to the brain, we chose to include all potential biomarkers.

There are a number of new serum biomarkers on the horizon for TBI including ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCH-L1),23,24 alpha-II spectrin breakdown products (SBDP145),23 and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).25 Serum levels of both UCH-L1 and GFAP have been shown to be significantly associated with intracranial lesions on CT in adults.24,25 This is a rapidly evolving field and, hopefully, this systematic review will serve as the foundation that other researchers in the field will continue to build on.

Although this research has not yet validated a biomarker(s) for clinical use, biomarkers of TBI have the potential to improve the management of children with TBI by providing more accurate early diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring progression of injury in the acute care setting. Secondary insults seriously impact outcome after TBI, and biomarkers could have a role in anticipating adverse events before they occur or identifying them early so they could be corrected swiftly. It will be important to evaluate the metabolism and biokinetic properties of these biomarkers specifically in children and not just extrapolate from animal models or adults. Biomarkers could also provide major opportunities for the conduct of clinical research including injury mechanism identification and the use of surrogate end-points. There is a need for a more focused approach to identify therapeutic targets in children with TBI. Biomarkers could help characterize pathophysiological mechanisms in children so new drugs could be developed for specific targets and predict drug response. If biologic markers could monitor specific physiological or pharmacological mechanisms, they could be used to select between multiple therapeutic targets for a drug by identifying those that are most sensitive to the intervention.

Another very important setting in which biomarkers may prove to be invaluable is in infants and toddlers with suspected abuse. Although the true incidence of abusive head trauma in children in the United States is unknown, we do know that fatal abusive head trauma is highest among children less than 1 year of age with a peak in incidence at 1–2 months of age.26 Because children with abusive head trauma often present with non-specific symptoms, the diagnosis is very difficult to make. Hence, the need for a more objective measure of injury, such as with serum biomarkers.

Because the pathology of TBI is so heterogeneous, one “magic” biomarker is unlikely to be the solution. There may be a panel of biomarkers that may prove to be most useful in distinguishing the different pathoanatomic processes that make up the injury. Ongoing studies will more fully elucidate the relationships between novel biomarkers and severity of injury and clinical outcomes in all severities of patients with TBI.

Conclusion

We must continue the exploration and validation of biomarkers for pediatric TBI using rigorous and more uniform research methodology, common data elements, and advances in proteomics, neuroimaging, genomics, and bioinformatics. There is a unique opportunity to use the insight offered by biochemical markers to shed light on the complexities of this injury process in children. The development of a clinical tool to help health care providers manage TBI in pediatric patients more effectively and improve their care is the ultimate goal.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Papa is a scientific consultant for Banyan Biomarkers, Inc. For the remaining authors, no competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Faul M. Xu L. Wald M.M. Coronado V.G. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States. Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths 2002–2006. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2010. . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choudhary J. Grant S.G. Proteomics in postgenomic neuroscience: the end of the beginning. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:440–445. doi: 10.1038/nn1240. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins M.O. Yu L. Coba M.P. Husi H. Campuzano I. Blackstock W.P. Choudhary J.S. Grant S.G. Proteomic analysis of in vivo phosphorylated synaptic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5972–5982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411220200. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denslow N. Michel M.E. Temple M.D. Hsu C.Y. Saatman K. Hayes R.L. Application of proteomics technology to the field of neurotrauma. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:401–407. doi: 10.1089/089771503765355487. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottens A.K. Kobeissy F.H. Golden E.C. Zhang Z. Haskins W.E. Chen S.S. Hayes R.L. Wang K.K. Denslow N.D. Neuroproteomics in neurotrauma. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2006;25:380–408. doi: 10.1002/mas.20073. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ragan D.K. McKinstry R. Benzinger T. Leonard J.R. Pineda J.A. Alterations in cerebral oxygen metabolism after traumatic brain injury in children. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:48–52. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.130. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coles J.P. Fryer T.D. Smielewski P. Rice K. Clark J.C. Pickard J.D. Menon D.K. Incidence and mechanisms of cerebral ischemia in early clinical head injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:202–211. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000103022.98348.24. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unterberg A.W. Stover J. Kress B. Kiening K.L. Edema and brain trauma. Neuroscience. 2004;129:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.046. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamoun R. Suki D. Gopinath S.P. Goodman J.C. Robertson C. Role of extracellular glutamate measured by cerebral microdialysis in severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 2010;113:564–570. doi: 10.3171/2009.12.JNS09689. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werner C. Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br. J. Anaesth. 2007;99:4–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem131. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cederberg D. Siesjö P. What has inflammation to do with traumatic brain injury? Childs Nerv. Syst. 2010;26:221–226. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-1029-x. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang K.K. Ottens A.K. Liu M.C. Lewis S.B. Meegan C. Oli M.W. Tortella F.C. Hayes R.L. Proteomic identification of biomarkers of traumatic brain injury. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2005;2:603–614. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.4.603. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kochanek P.M. Berger R.P. Bayr H. Wagner A.K. Jenkins L.W. Clark R.S. Biomarkers of primary and evolving damage in traumatic and ischemic brain injury: diagnosis, prognosis, probing mechanisms, and therapeutic decision making. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 2008;14:135–141. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f57564. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papa L. Robinson G. Oli M. Pineda J. Demery J. Brophy G. Robicsek S.A. Gabrielli A. Robertson C.S. Wang K.W. Hayes R.L. Use of biomarkers for diagnosis and management of traumatic brain injury patients. Expert Opinion on Medical Diagnostics. 2008;2:937–945. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2.8.937. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger R.P. The use of serum biomarkers to predict outcome after traumatic brain injury in adults, children. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:315–333. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200607000-00004. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adelson P.D. Pineda J. Bell M.J. Abend N.S. Berger R.P. Giza C.C. Hotz G. Wainwright M.S. Common data elements for pediatric traumatic brain injury: recommendations from the working group on demographics and clinical assessment. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:639–653. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1952. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger R.P. Beers S.R. Papa L. Bell M. Common data elements for pediatric traumatic brain injury: recommendations from the biospecimens and biomarkers workgroup. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:672–677. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1861. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duhaime A.C. Holshouser B. Hunter J.V. Tong K. Common data elements for neuroimaging of traumatic brain injury: pediatric considerations. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:629–633. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1927. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]