Abstract

Background

Non-adherence is a major concern in the treatment of diabetes mellitus and undermines the goals of treatment. The objective of this study was to determine the magnitude of non-adherence and its contributing factors among diabetes mellitus patients attending the diabetes mellitus clinic at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital.

Objective

To assess prevalence and factors contributing to non-adherence to antidiabetic medication among diabetes mellitus patients in the diabetic clinic at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was adopted at the diabetes clinic, Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, between July and October 2020. Study participants were systemically sampled, and data regarding their medication non-adherence was collected using a structured questionnaire, based on the Hill-Bone medication adherence scale. Data entry was done using Microsoft Excel Version 2010, and analysis was carried out using STATA version 13. The odds ratio was used to determine the strength of association between diabetic medication non-adherence and associated factors. The cutoff value for all statistical significance tests was set at p < 0.05 with a confidence interval of 95%.

Results

A total of 257 participants were recruited with a 100% response rate. More than one-third (98, 38.1%) of the participants were non-adherent to their antidiabetic medication. Age above 60 years (AOR = 6.26, 95% CI = 1.009–39.241, P = 0.049) and duration of diabetes mellitus above 5 years (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.034–3.392, P = 0.038) were independently associated with non-adherence to antidiabetic medication.

Conclusion

The prevalence of non-adherence to antidiabetic medication was higher than that revealed in previous studies in Uganda. Patients with age above 60 years were six times more likely to be non-adherent to their anti-diabetic medications. Patient education is important to address the challenges of medication non-adherence.

Keywords: non-adherence, contributing factors, prevalence, antidiabetic drugs, Uganda

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major public health issue globally. Current estimates indicate that nearly 415 million people are affected and are set to escalate to 642 million by the year 2040, further 193 million people with diabetes remain undiagnosed due to the often mild or asymptomatic nature of this condition especially in type 2 DM (T2DM).1

Adherence to anti-diabetic medication is one of the major pillars of health service excellence and is defined as the proportion of the prescribed doses of the drug taken by a patient over a specified period or the extent to which the patient is taking their medicines as prescribed by a healthcare professional.2

Non-adherence to antidiabetic medication remains the most common reason for poor health outcomes among people with diabetes. The levels of non-adherence to antidiabetic recommendations are highly variable but have significant effects on diabetes outcomes and the effectiveness of treatments.3,4 Continuous evaluation of adherence is vital to identify factors and barriers contributing to non-adherence and its better management through timely identification of contributing factors and provision of individualized suitable recommendations that are essential for better healthcare management.5

Methods for measuring medication adherence are broadly categorized as either direct or indirect. Direct methods include directly observed treatment and monitoring of specific drug metabolite or biological markers. Direct methods are considered more accurate than indirect methods, but they are quite expensive and not used routinely in clinical practice. Indirect methods include self-reports, patient questionnaires, patient diaries, prescription refill records, electronic medication monitors, and patient clinical response. However, each indirect method has strengths and weaknesses and the use of a specific method to determine the level of medication adherence depends on the availability of required data and the nature of the clinical care setting.6

Poor persistence with and adherence to antidiabetic medication exposes the patient to disease complications with fatal consequences, including failure to achieve glycemic control goals,7 contributes to the suboptimal glycemic control and continues to be one of the major barriers to effective diabetes mellitus management.8

A study in India established that 55.14% of the study participants were non-adherent and the major contributing factors of non-adherence to antidiabetic treatment were ignorance for lifestyle modification ie 83.78%. Among them, 59.48% did not take the prescribed medicine in time, most of them 85.71% did not follow a diabetes diet and less than half (46.61%) did not monitor blood glucose levels regularly due to poor self-discipline. Gender, occupation, and educational status were the significant contributors to non-adherence.9

In Saudi Arabia, a therapeutic non-compliance prevalence of 67.9% (ie 69.34% in males and 65.45% in females) was largely associated with females, illiteracy, urban population, irregularity of follow-ups, non-adherence to antidiabetic medication, non-adherence to exercise regimen, insulin, and insulin with oral metformin.10

A study done by Gertrude Afriyie and others at the University of Ghana among 259 patients within the ages of 26 years and 88 years established a proportion of non-adherence to the antidiabetic medication of 34.7% and associated factors that turned out to be statistically significant for non-adherence included; age, educational level, presence of comorbidities, and financial support.11 While in Ethiopia at Adama Hospital medical college, the prevalence of non-adherence was 58.6% (95% CI: 54.7, 62.4), and major depressive disorder, one or more diabetes mellitus complications, and average income greater than 1000 birr were found to be independent predictors of medication non-adherence, respectively.12

At a general hospital in Ethiopia, a non-adherence to antidiabetic medication prevalence of 31.2% amongst diabetes mellitus patients was established while side effects of medications, the complexity of regimen, failure to remember, educational level, and monthly income were major associated factors identified in the study.13

Fewer studies on non-adherence to antidiabetic medication have been conducted in Uganda. However, a non-adherence prevalence to the antidiabetic medication of 28.9% at Mulago hospital in Kampala district was mainly associated with female gender, illiteracy, low social economic status, poor handwriting on prescriptions, and delayed intervals to follow up on treatments.14 Hence, this study aimed at determining the prevalence and identifying factors associated with non-adherence to anti-diabetes medication among patients in the Diabetes mellitus clinic at Mbarara regional referral hospital, southwestern Uganda.

Methods and Materials

Study Design

Descriptive cross-sectional study was adopted, Outcome variables were non-adherence prevalence and factors contributing to non-adherence to antidiabetic medication.

Study Setting and Period

The study was conducted in the Diabetic Clinic at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) located in Mbarara City, approximately 260 km, southwest of Kampala, the capital city of Uganda. It is a government-owned referral and teaching hospital for Mbarara University Medical School with a patient capacity of approximately 350 beds.

The general medical care in the hospital is free, and the Diabetic Clinic is one of the major ambulatory clinics operated once a week within the hospital.

Data were collected from eligible participants in the Diabetic clinic between July 2020 and October 2020.

Study Population

Diabetic patients (both type 1 and type 2), above 18 years of age who attended the Diabetic clinic at MRRH during the study period from July 2020 to October 2020 and gave informed consent.

Definition of Variables

Non-adherence (needs to be defined according to the 9-items medication adherence Hill-bone scale).

Sampling Procedure and Sample Size Estimation

A systematic random sampling technique was used to select study participants. The sample size was calculated using finite population formula and the prevalence of non-adherence to the antidiabetic medication of 28.9% in Uganda by Kalyango et al14 was used for this calculation. Using the formula single population proportion;15

|

Where:

Zα = Standard deviation at 95% confidence interval corresponding to 1.96

p = assumed population of diabetes mellitus patients who are non-adherent to treatment, results of a study at Mulago hospital14 were used, so P = 28.9%

1-P = is the probability of diabetes mellitus patients who were adhering to their antidiabetic medication, therefore 1-P=71.1%

e = level of precision (in proportion of one, therefore considering 5%, e = 0.05)

n = sample size estimation of patients with diabetes mellitus

Estimated sample size,

Estimated size (N) =316

The number of active patients at the Diabetes clinic (MRRH) was approximately 1074 (source; Diabetes clinic records). The finite population correction factor (n)

|

Total number of active patients (no) = 1074 (adopted from Diabetes clinic records)

Estimated sample size (N) = 316

Therefore, sample size (n) = 245 patients

Adding 5% for incomplete information and withdraw from the study, 245 × 0.05 = 12

Total target sample = 245 + 12 = 257.

Sampling interval = 1074/257 = 4, interviewed every fourth patient on the clinic appointment list starting from a number randomly selected from 1 to 4.

Data Collection Procedure

A structured investigator-administered pre-tested questionnaire was used for each participant to collect information on socio-demographic and adherence characteristics. A checklist was used to document diseases (Diabetes mellitus and other comorbidities) and drugs’ (anti-diabetic medication) information for each patient.

A detailed history was acquired (English), translated where necessary for patients who do not understand English.

Non-adherence to antidiabetic medication was assessed based on the Hill-Bone Medication Adherence scale.16

Data Quality Control

A registered nurse in the Diabetes clinic was recruited and well trained in data collection techniques. The data collection instruments were pretested on five (5) patients in the Diabetes clinic to identify possible sources of errors that would arise during data collection. Those five patients were not part of the sample population, and the questionnaire was administered to them to measure the inter-respondent agreement. The agreement of more than 78% was a measure that the items of the questionnaire would provide a picture of factors associated with non-adherence to antidiabetic medication in the study population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were strictly adhered to. A common pretested questionnaire that was edited before its use was used for data collection. The questionnaire was also checked for completeness before data collection to ensure valid data was obtained. Identification of participants was done using numerical codes. Details of participants were kept under lock and key for privacy and confidentiality purpose throughout the study. There was no disclosure of participants’ identities to the public, and all identities were removed before publication.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Data on questionnaires were checked for completeness, coded and entered in Microsoft Excel version 2010, and then exported to Stata version 13. Socio-demographic and clinical factors were summarized as means and standard deviation (for continuous variables). Percentages and frequencies were used for categorical variables. Hill-bone medication adherence scale was used to determine non-adherence to anti-diabetic medications. The factors associated with non-adherence to antidiabetic medication were identified using logistic regression. Binary logistic regression was carried out using Stata. Prevalence Ratios were used to compare the prevalence of non-adherence across the independent variables. Factors with a p-value ≤0.20 at univariate logistic regression and with biological plausibility were considered for multivariate analysis. Those factors with p-value <0.05 were considered significant.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki.17 Approval to carry out the study was acquired from the Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, and finally from Mbarara University Research Ethics Committee (MUST-REC). After approval by the MUST-REC (Letter with reference number MUREC 1/7), permission was thought from the administration of Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital before data collection in the Diabetes mellitus clinic.

Precautions for Prevention of Covid-19 Transmission

Participants who were initially screened for body temperature and possible signs and symptoms of covid 19 were considered for data collection. These were further given more information on how covid 19 is transmitted and finally preventive measures of handwashing, wearing face masks and social distancing were always emphasized before any interaction with the study participants.

Results

The study had a response rate of 100% of 257 respondents.

General Characteristics of Study Participants

The study involved 257 participants consisting of 168 (65.4%) females and 89 (34.6) males. The majority (64.6%) of the participants were in the age range of 25–60 years (53 ± 13.3); almost one-quarter (23.4%) had no formal education and almost one-half (122, 47.5%) were protestants and one-third (85, 33.1%) were farmers. A majority (192, 74.7%) had no family history of diabetes mellitus (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants at the Diabetes Clinic of MRRH Between July and October 2020

| Variable | Categories | Frequency N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 9 (3.5) |

| 25–60 | 166 (64.6) | |

| Above 60 | 82 (31.9) | |

| Gender | Female | 168 (65.4) |

| Male | 89 (34.6) | |

| Education | Not educated | 60 (23.4) |

| Primary/Intermediate | 106 (41.3) | |

| Secondary | 56 (21.8) | |

| Tertiary | 35 (13.6) | |

| Religion | Protestant/Anglican | 122 (47.5) |

| Catholic | 80 (31.1) | |

| Muslims | 39 (15.2) | |

| Pentecostal | 16 (6.2) | |

| Tribe | Banyankole | 187 (72.8) |

| Bakiga | 30 (11.7) | |

| Baganda | 27 (10.5) | |

| Others | 13 (5.1) | |

| Family History of Diabetes | Yes | 65 (25.3) |

| No | 192 (74.7) | |

| Employment Status | Peasant/farmer | 85 (33.1) |

| Unemployed | 63 (24.5) | |

| Employed | 58 (22.6) | |

| Entrepreneur | 51 (19.8) |

LifeStyle and Disease Characteristics

A majority (253, 98.4%) of the study participants had Type 2 diabetes mellitus and more than one-half (160, 62.3%) had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus within five years. More than three quarters (214, 83.3%) of the participants had comorbidities of which hypertension (143, 66.8%) was the most common. The majority (148, 81.3%) of the participants had diabetes mellitus-related complications of which 119 (79.9%) had been diagnosed with neuropathy. More than one-half (142, 55.3%) of the participants were on Metformin and glibenclamide antidiabetic regimen (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lifestyle and Disease Characteristics Among Study Participants at the Diabetes Mellitus Clinic of MRRH Between July to October 2020

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol intake | Yes | 11 | 4.3 |

| No | 246 | 95.7 | |

| Physical exercise | Yes | 168 | 65.37 |

| No | 89 | 34.6 | |

| Smoking tobacco | Yes | 5 | 1.9 |

| No | 252 | 98.1 | |

| BMI | Normal | 99 | 38.5 |

| Overweight | 93 | 36.2 | |

| Obese | 65 | 25.3 | |

| Type of Diabetes | Type 1 | 4 | 1.6 |

| Type 2 | 253 | 98.4 | |

| Duration Diabetes | 5 Years and Below | 160 | 62.3 |

| Above 5 Years | 97 | 37.7 | |

| Presence of Comorbidity | Yes | 214 | 83.3 |

| No | 43 | 16.7 | |

| Type of Comorbidity | Hypertension | 143 | 66.8 |

| HIV | 52 | 24.3 | |

| Others | 19 | 18.4 | |

| Presence of Diabetes complication(s) | Yes | 148 | 81.3 |

| No | 109 | 18.7 | |

| Type of Diabetes Complication | Neuropathy | 119 | 79.9 |

| Retinopathy | 18 | 12.1 | |

| Others | 11 | 7.4 | |

| Antidiabetics used | Metformin | 35 | 13.6 |

| Insulin | 36 | 14.0 | |

| Glibenclamide | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Metformin and Insulin | 43 | 16.7 | |

| Metformin and Glibenclamide | 142 | 55.1 |

Prevalence of Non-Adherence

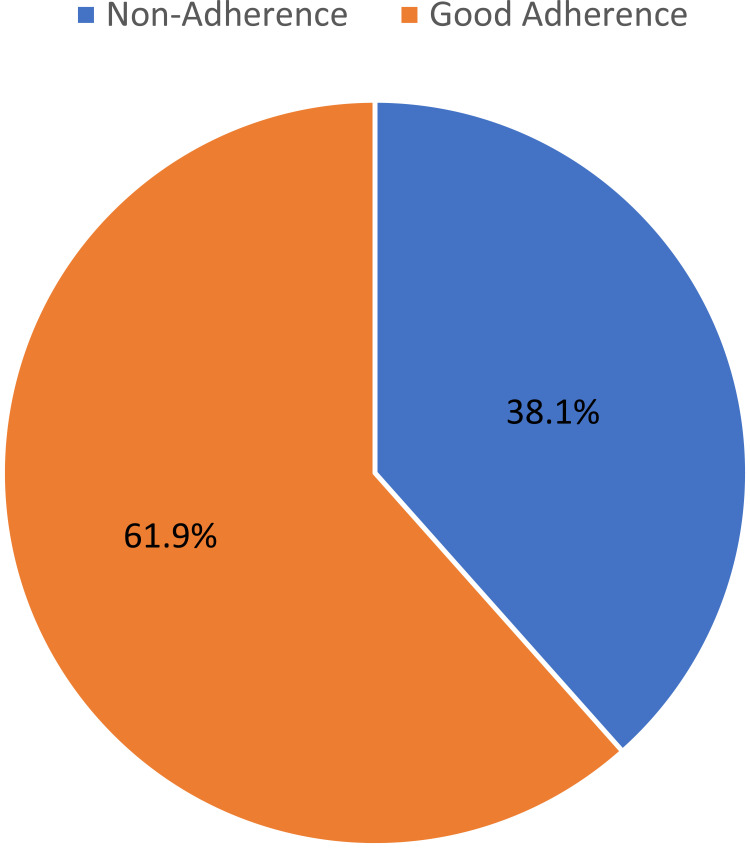

Over one-third, (98, 38.1%) of the study participants were non-adherent to antidiabetic medication (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The level of antidiabetic medication non-adherence among participants in the Diabetes mellitus clinic at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital from July to October 2020.

Reasons for Non-Adherence to Antidiabetic Medication

More than one-quarter (50, 25.5%) of the study participants reported that drug(s) being expensive was the cause for antidiabetic medication non-adherence and less than one-quarter (38, 19.4%) ascribed non-adherence to not understanding instruction(s) on how to take prescribed medicine(s) and less than one-quarter (32, 16.3%) of the study participants attributed non-adherence to unavailability of the drug product to them (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patients’ Reasons for Non-Adherence Among Participants in the Diabetes Clinic at MRRH Between July to October 2020

| Factors | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Drug is expensive to buy on daily basis | 50 | 25.5 |

| Does not understand prescriptions | 38 | 19.4 |

| Drug product not available | 32 | 16.3 |

| Forgets to take the drug | 24 | 12.2 |

| Patient prefers not to take the drug | 24 | 12.2 |

| Not willing to take the drug | 16 | 8.2 |

| Cannot swallow or administer drug | 10 | 5.2 |

| Others | 02 | 1.0 |

Factors Associated with Non-Adherence to Antidiabetic Medication

Univariate Analysis

Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that age range above 60 years (COR = 5.47, 95% CI = 1.068–27.993, P = 0.041) and living with diabetes mellitus for duration above five years since diagnosis (COR = 2.15, 95% CI = 1.281–3.624, P = 0.004) were significantly associated with antidiabetic medication non adherence (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate Logistic Regression of Factors Associated with Antidiabetic Medication Non-Adherence Among Study Participants at the Diabetic Clinic of MRRH, Mbarara, Uganda

| Variable | Category | Non-Adherence | Univariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No N=159 (%) |

Yes N=98 (%) |

COR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | 1 | ||

| 25–60 | 120 (72.3) | 46 (27.7) | 1.34 | 0.269–6.697 | 0.720 | |

| Above 60 | 32 (39.0) | 50 (61.0) | 5.47 | 1.068–27.993 | 0.041* | |

| BMI | Normal | 60 (60.6) | 39 (39.4) | 1 | ||

| Overweight | 55 (59.1) | 38 (40.9) | 1.06 | 0.597–1.894 | 0.84 | |

| Obese | 44 (67.7) | 21 (32.3) | 0.73 | 0.380–1.418 | 0.36 | |

| Gender | Male | 48 (53.9) | 41 (46.1) | |||

| Female | 111 (66.1) | 57 (33.9) | 0.60 | 0.356–1.016 | 0.058* | |

| Education | Primary/Intermediate | 71 (67.0) | 35 (33.0) | 1 | ||

| Not educated | 32 (53.3) | 28 (46.7) | 1.78 | 0.928–3.396 | 0.083 | |

| Secondary | 36 (64.3) | 20 (35.7) | 1.13 | 0.571–2.225 | 0.730 | |

| Tertiary | 20 (57.1) | 15 (42.9) | 1.52 | 0.695–3.327 | 0.293 | |

| Physical exercise performance | Yes | 104 (61.9) | 64 (38.1) | 1 | ||

| No | 55 (61.8) | 34 (38.2) | 1.00 | 0.592–1.705 | 0987 | |

| Smoking tobacco | Yes | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 155 (61.5) | 97 (38.3) | 2.50 | 0.276–22.726 | 0.415 | |

| Alcohol consumption | Yes | 4 (36.4) | 7 (63.6) | 1 | ||

| No | 155 (63.0) | 91 (37.0) | 0.34 | 0.096–1.177 | 0.088* | |

| Type of Diabetes | Type 1 | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 1 | ||

| Type 2 | 157 (62.1) | 96 (37.9) | 0.61 | 0.148–2.482 | 0.487 | |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 5 years and below | 110 (68.7) | 50 (31.3) | 1 | ||

| Above 5 years | 49 (50.5) | 48 (49.5) | 2.15 | 1.281–3.624 | 0.004* | |

| Presence of Complications | Yes | 132 (63.3) | 77 (36.7) | 1 | ||

| No | 27 (56.3) | 21 (43.7) | 1.33 | 0.706–2.518 | 0.375 | |

| Presence of Comorbidities | Yes | 85 (62.5) | 51 (37.5) | 1 | ||

| No | 74 (61.2) | 47 (38.8) | 1.05 | 0.424–0.849 | 0.825 | |

| Religion | Protestants | 76 (62.3) | 46 (37.7) | 1 | ||

| Catholics | 53 (66.2) | 27 (33.8) | 0.84 | 0.466–1.519 | 0.567 | |

| Muslims | 19 (48.7) | 20 (51.3) | 1.74 | 0.841–3.597 | 0.136* | |

| Pentecostal | 8 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | 0.83 | 0.236–2.897 | 0.765 | |

| Others | | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.55 | 0.056–5.452 | 0.610 | |

| Employment | Employed | 33 (56.9) | 25 (43.1) | 1 | ||

| Peasant/farmer | 45 (52.9) | 40 (47.1) | 1.17 | 0.599–2.297 | 0.641 | |

| Entrepreneur | 30 (71.4) | 12 (28.6) | 0.53 | 0.226–1.232 | 0.140* | |

| Un employed | 45 (71.4) | 18 (28.6) | 0.53 | 0.248–1.123 | 0.097* | |

| Others | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 0.66 | 0.150–2.899 | 0.582 | |

| Tribe | Banyankole | 117 (62.6) | 70 (37.4) | 1 | ||

| Bakiga | 18 (60.0) | 12 (40.0) | 1.11 | 0.506–2.451 | 0.788 | |

| Buganda | 14 (51.9) | 13 (48.1) | 1.55 | 0.689–3.492 | 0.288 | |

| Others | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | 0.50 | 0.133–1.884 | 0.307 | |

| Antidiabetic regimen used | Metformin | 24 (66.7) | 12 (33.3) | 1 | ||

| Insulin | 19 (52.8) | 17 (47.2) | 1.95 | 0.741–5.140 | 0.176* | |

| Metformin and insulin | 31 (72.1) | 12 (27.9) | 0.84 | 0.318–2.242 | 0.735 | |

| Metformin and Glibenclamide | 85 (59.9) | 57 (40.1) | 1.46 | 0.664–3.219 | 0.344 | |

Notes: NB: those with a * had a p-value ≤ 0.20 and were considered for multivariate logistic regression analysis; texts in bold: statistically significant.

Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate logistic regression involving variables that had a p-value ≤0.20 at univariate logistic regression was done. Age range above 60 years (AOR = 6.26, 95% CI = 1.009–39.241, P=0.049) and Duration of diabetes mellitus above 5 years since diagnosis (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.034–3.391, P = 0.038) were associated with antidiabetic medication non-adherence and had a statistically significant relationship. Not being employed (AOR = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.139–0.977, P = 0.045) was protective and therefore, less likely to lead to antidiabetic medication non-adherence (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate Logistic Regression of Factors Associated with Antidiabetic Medication Non-Adherence Among Study Participants at the Diabetic Clinic of MRRH, Mbarara, Uganda

| Variable | Category | Non-Adherence | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No N (%) |

Yes N (%) |

AOR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Gender | Male | 48 (53.9) | 41 (46.1) | 1 | ||

| Female | 111 (66.1) | 57 (33.9) | 0.57 | 0.312–1.044 | 0.069 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | 1 | ||

| 25–60 | 120 (72.3) | 46 (27.7) | 1.19 | 0.204–6.962 | 0.845 | |

| Above 60 | 32 (39.0) | 50 (61.0) | 6.29 | 1.009–39.241 | 0.049 | |

| Education | Primary | 71 (67.0) | 35 (33.0) | 1 | ||

| Not educated | 32 (53.3) | 28 (46.8) | 1.36 | 0.634–2.933 | 0.426 | |

| High school | 36 (64.3) | 20 (35.7) | 1.84 | 0.828–4.073 | 0.135 | |

| Tertiary | 20 (57.1) | 15 (42.9) | 1.88 | 0.663–5.317 | 0.235 | |

| Duration of Diabetes (years) | 5 years and below | 110 (68.8) | 50 (31.2) | 1 | ||

| Above 5 years | 49 (50.5) | 48 (49.5) | 1.87 | 1.034–3.392 | 0.038 | |

| Employment status | Employed | 33 (56.9) | 25 (43.1) | 1 | ||

| Farmers | 45 (52.9) | 40 (47.1) | 0.85 | 0.344–2.110 | 0.730 | |

| Entrepreneur | 30 (71.4) | 12 (28.6) | 0.57 | 0.212–1.519 | 0.259 | |

| Un employed | 45 (71.4) | 18 (28.6) | 0.37 | 0.139–0.977 | 0.045 | |

| Others | 6 (66.6) | 3 (33.3) | 0.21 | 0.036–1.257 | 0.088 | |

| Antidiabetic regimen used | Metformin | 24 (66.7) | 12 (33.3) | 1 | ||

| Insulin | 19 (52.9) | 17 (47.2) | 1.93 | 0.652–5.728 | 0.234 | |

| Metformin and insulin | 31 (72.1) | 12 (27.9) | 0.73 | 0.243–2.178 | 0.570 | |

| Metformin and Glibenclamide | 85 (59.9) | 57 (40.1) | 1.42 | 0.582–3.466 | 0.440 | |

Notes: Texts in bold: statistically significant.

Surrogate Makers

Mean HbA1c of those who were non-adherent was 9.43%±2.70; which was not significantly higher (p value = 0.266) compared to HbA1c of 9.07 ± 2.39 of those who were adherent. However, their mean FBG was significantly higher than that of those who were adherent (10.01 ± 5.26 vs 8.33 ± 5.04; p value = 0.011) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of Student’s t-test for Surrogate Markers in Relation to Antidiabetic Medication Non-Adherence Among Study Participants at the Diabetic Clinic of MRRH Between July to October 2020

| Variables | Non-Adherence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | P-value | |||||

| Mean | SD | CI | Mean | SD | CI | ||

| HbA1C (%) | 9.43 | 2.70 | 8.89–9.98 | 9.07 | 2.39 | 8.70–9.45 | 0.266 |

| FBG (Mmol/l) | 10.01 | 5.26 | 8.95–11.06 | 8.33 | 5.04 | 7.54–9.12 | 0.011 |

Notes: Texts in bold: statistically significant.

Abbreviations: HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; FBG, fasting blood glucose.

Discussion

Prevalence of Non-Adherence to Antidiabetic DM Medication Among DM Patients

In this study, more than one-third (98, 38.1%) of the participants were non-adherent to their anti-diabetic medication. The findings in this study are lower compared to those from a study done in the Quebec region of Canada among those newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus which had a prevalence of 52.0% (n = 3106).18 The variation may be explained by the findings being among newly diagnosed patients yet in this study, all participants had been diagnosed with Diabetes mellitus for at least more than one month. It, therefore, means that participants in this study had had this condition for some time, and maybe some had received education and adherence counseling, thus having a lower prevalence of non-adherence. Our findings are quite surprisingly at variance with other studies which all reported a quite higher prevalence of non-adherence. For example, a cross-sectional study in India established that 55.14% of the participants were non-adherent to their antidiabetic medications,9 and a therapeutic non-compliance prevalence of 67.9% (n = 318, 95% CI 63.59–72.02%) was reported in Saudi Arabia, Demonstrating a high rate of non-compliance among the Diabetes patients in the Al Hasa region.10 This may suggest good adherence counseling at Mbarara Regional Referral hospital or other factors that may have been beyond the scope of this study. This study agrees within an average none adherence of 54% both in the developed and developing countries (Cameroon 54.4%, Ethiopia 58.6%, Egypt 47.9 and Turkey 53.9%).12 However, a study done in Uganda revealed findings that are slightly lower than our findings (38.1%) with an overall prevalence of non-adherence among the participants that was suboptimal at 28.9%14 making our findings comparatively high. Perhaps this may be due to differences in the study population and the study setting of the different studies but also in our study, the majority (214, 83.3%) had comorbidities, and studies have indicated that the number of drugs taken by patients is dependent on comorbidities. Therefore, a patient with a complex regimen is challenged to continue adhering to all prescribed medications. This is more likely to be the contributor to the observed slightly higher level of non-adherence since patients with co-morbidities have a divided commitment to managing several comorbidities. However, this deviates from the results of the study by Lunghi et al,18 in which multiple medications were associated with good antidiabetic medication adherence.

Factors Contributing to Non-Adherence to Anti-Diabetic DM Medication Among DM Patients

In this study, age above 60 years and duration of diabetes mellitus of above 5 years since diagnosis were independently associated with antidiabetic medication non adherence. The reasons for non-adherence in our study differ from those in a study done in Canada, which revealed that drugs being expensive for patients to buy on daily basis (25.5%), lack of understanding of prescription instructions (19.4%), unavailability of free medicines in public hospitals (16.3%), forgetfulness (12.2%) and patients’ preference for not following prescription instructions (12.2%) as factors strongly associated with non-adherence to DM drugs.18

Findings from our study reveal that the female gender was 57% less likely to non-adhere to their antidiabetic medication. This is in agreement with findings by Gelaw et al,19 stating that the female gender was more adherent to their medications, possibly due to the reason that most females spend most of their time at home and are thus more likely to follow prescription instructions agreed upon with the prescribers due to convenient home environment.

Multivariate logistic regression revealed that increasing age above 24 years had a positive association with the likelihood of non-adherence to antidiabetic medications. Age groups between 24 and 60 years, and above 60 years were 1.1 times more likely to be non-adherent to their medications, respectively. This finding in our study may be because older adults in our setting are less financially capable to access medications from drug outlets, as prescribed by the healthcare provider. This will as well explain the contrasting findings in a previous study in Ethiopia, where older adults were more likely to be adherent to their medications, due to the possible difference in social-economic support to the elderly people.20

Duration of Diabetes for more than 5 years since diagnosis was also significantly associated with non-adherence to antidiabetic medication (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.034–3.391, P = 0.038). This is in agreement with the study from Saudi Arabia and Eastern Uganda by Almaghaslah et al and Bagonza et al.3,21 It demonstrates that the longer the duration of diabetes, the more the rate of non-adherence. This finding may be explained by the anxiety and fear that patients experience during the early years following diagnosis and thus become committed to managing their disease, but the commitment gradually wears out as they adapt to the burden of the disease and non-adherence emerges.

The mean HbA1c of those who were non-adherent was 9.43%, their mean FBS was 10.01 mmol/l, P = 0.01, and was significantly associated with antidiabetic medication non-adherence.

Limitations

Due to Covid 19 pandemic, some patients were not comfortable with participating in research; this could have affected the quality of interaction and interview.

There was a challenge of space within the Diabetes mellitus clinic premise, with limited privacy during interviews. This could have compromised the privacy standards and thus impacted the quality of patient responses.

Some study participants may have failed to recall accurately (recall bias) their previous experiences regarding adherence to their antidiabetic medication, thus ending up giving incomplete information that may have compromised study outcomes.

Strength of the Study

The response rate was 100% which most likely gave a better estimate of the study outcome variables.

Conclusion

More than one-third of the study participants were non-adherent to their antidiabetic medication, with medication expense being the most frequent reason mentioned for non-adherence to antidiabetic medication. Patients aged 60 years and above, and those having more than 5 years of the disease since diagnosis, were 6.2 and 1.1 times more likely to be non-adherent to their anti-diabetic medications.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all members of staff at the Department of Pharmacy, Diabetes Clinic-MRRH, DGRT of Mbarara University of Science and Technology, and all individuals who have supported us towards the completion of this research project.

Funding Statement

This research work was funded by personal resources.

Abbreviations

CADS, Conventional Antidiabetic Drugs; CVS, Cardiovascular System; DGRT, Directorate of Postgraduate Training and Research; DKA, Diabetic Ketoacidosis; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; FBG, Fasting Blood Glucose; HbA1c, Glycated Hemoglobin; HHS, Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Non-Ketotic Syndrome; MRRH, Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital; MUST, Mbarara University of Science and Technology; REC, Research Ethics Committee; RBG, Random Blood Glucose; T2DM, Type 2 Diabetes mellitus; TIDM, Type 1 Diabetes mellitus; AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratios; CI, Confidence Interval; OR Odds Ratios; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The preprint of this article is available at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-571953/v1.

Ethical Approval and Consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.17 Voluntary recruitment was done, and informed consent was signed by study participants. Informed consent from study participants was obtained after a full explanation of the details of the study to them in English and interpreted to local language (Runyankole) for those participants who did not understand English. Participants were not forced to enroll themselves if they did not want to. Study participants were also at liberty to withdraw from the study at any time as they wished without coercion or compromise of care they were entitled to.

Consent for Publication

All authors agreed to the submission of this manuscript for publication in addition to the consent to publish which was included in the informed consent form which attained ethical and participant approval.

Author Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article and revising it critically for important scholarly content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Al-Lawati JA. Diabetes mellitus: a local and global public health emergency! Oman Med J. 2017;32(3):177. doi: 10.5001/omj.2017.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yazew KG, Walle TA, Azagew AW. Prevalence of anti-diabetic medication adherence and determinant factors in Ethiopia: a systemic review and meta-analysis, 2019. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2019;11:100167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2019.100167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagonza J, Rutebemberwa E, Bazeyo W. Adherence to anti-diabetic medication among patients with diabetes in eastern Uganda; a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0820-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedrick F, Temu M. Factors contributing to non-adherence to diabetes treatment among diabetic patients attending clinic in Mwanza city. East Afr J Public Health. 2012;9(3):90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heissam K, Abuamer Z, El-Dahshan N. Patterns and obstacles to oral antidiabetic medications adherence among type 2 diabetics in Ismailia, Egypt: a cross-section study. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.177.4025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerci B, Chanan N, Kaur S, Jasso-Mosqueda JG, Lew E. Lack of treatment persistence and treatment nonadherence as barriers to glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(2):437–449. doi: 10.1007/s13300-019-0590-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkatesan M, Dongre AR, Ganapathy K. A community-based study on diabetes medication nonadherence and its risk factors in rural Tamil Nadu. Indian J Community Med. 2018;43(2):72. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_261_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattarai B, Bista B, Shrestha S, Budhathoki B, Dhamala B. Contributing factors of non-adherence to treatment among the patients with type II diabetes mellitus. J Manmohan Mem Inst Health Sci. 2019;5(1):68–78. doi: 10.3126/jmmihs.v5i1.24075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan AR, Lateef ZN-A-A, Al Aithan MA, Bu-Khamseen MA, Al Ibrahim I, Khan SA. Factors contributing to non-compliance among diabetics attending primary health centers in the Al Hasa district of Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2012;19(1):26. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.94008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afriyie G. Non-Adherence to Medication and Associated Factors Among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients Attending Tema General Hospital. The University of Ghana; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusa W, Tolessa D, Abdeta T. Type II DM medication non-adherence in Adama Hospital Medical College, Central Ethiopia. East Afr J Health Biomed Sci. 2019;3(1):31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kassahun A, Fanta Gashe EM, Rike WA. Nonadherence and factors affecting adherence of diabetic patients to anti-diabetic medication in Assela General Hospital, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(2):124. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.171696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalyango JN, Owino E, Nambuya AP. Non-adherence to diabetes treatment at Mulago Hospital in Uganda: prevalence and associated factors. Afr Health Sci. 2008;8(2):67–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naing L, Winn T, Rusli B. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci. 2006;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan A, Horne R, Hankins M, Chisari C. The Medication Adherence Report Scale: a measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(7):1281–1288. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WMA. Declaration of Helsinki – ethical Principles For Medical Research Involving Human Subjects [Press release]; 2018. [PubMed]

- 18.Lunghi C, Zongo A, Moisan J, Grégoire J-P, Guénette L. Factors associated with antidiabetic medication non-adherence in patients with incident comorbid depression. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31(7):1200–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelaw BK, Mohammed A, Tegegne GT, et al. Nonadherence and contributing factors among ambulatory patients with antidiabetic medications in Adama Referral Hospital. J Diabetes Res. 2014;2014:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2014/617041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abate TW. Medication non-adherence and associated factors among diabetes patients in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar city administration, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4205-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almaghaslah D, Abdelrhman AK, AL-Masdaf SK, et al. Factors contributing to non-adherence to insulin therapy among type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Asser region, Saudi Arabia. Biomed Res. 2018;29(10). doi: 10.4066/biomedicalresearch.29-18-503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]