Abstract

Violence against healthcare workers is a serious and growing problem. The objectives of this cross-sectional study were to: a) describe the frequency of workplace violence (WPV) against emergency department (ED) workers; b) identify demographic and occupational characteristics related to WPV; and c) identify demographic and occupational characteristics related to feelings of safety and level of confidence when dealing with WPV. Survey data were collected from 213 workers at six hospital EDs. Verbal and physical violence was prevalent in all six EDs. There were no statistically significant differences in the frequency of violence for age, job title, patient population, and hospital location. Sexual harassment was the only category of violence affected by gender with females having a greater frequency. Feelings of safety were positively related to the frequency of WPV. Females were significantly more likely to feel unsafe and have less confidence in dealing with WPV. The study findings indicate that all ED workers are at risk of violence, regardless of personal and occupational characteristics. Feelings of safety are related to job satisfaction and turnover. Violence has serious consequences for the employers, employees, and patients. It is recommended that administration, managers and employees collaborate to develop and implement prevention strategies to reduce and manage the violence.

Keywords: Violence, Emergency Departments, Safety, Confidence

Introduction

Background

Violence against healthcare workers is a real and growing problem in the United States (Gates, 2004; Howard & Gilboy, 2009; McPhaul, and Lipscomb, 2009; NIOSH, 2002; Simonowitz, 1996; U.S. Department of Labor, 2010) and abroad (Al-Sahlawi, Zahid, Shahid, Hatim, & Al-Bader, 1999; Ayranci, 2005; Boz et al., 2006; Fernandes et al., 1999; Hesketh et al., 2003; Hodge & Marshal, 2007; Laudau & Bendalak, 2008; Merecz, Rymanszewska, Moscicka, Kiejna, & Jarosz-Nowak, 2006; Zahid, Al-Saahlawi, Shahid, Hatim, & Al-Bader, 1999.) Rates of workplace assault are higher for healthcare workers than any other industry. This is particularly true in the Emergency Department (ED), which has the highest rate of violence for nurses working in hospitals (Emergency Nurses Association, 2010a; Emergency Nurses Association, 2010b; Gacki-Smith et al., 2009; Pich, Hazelton, Sundin, & Kable, 2010).

No ED healthcare occupation is immune from the problem. Nurses, aides/technicians (American Nurses Association, 2006; Crilly, Chaboyer, Creedy, 2004; Emergency Nurses Association, 2010a; Emergency Nurses Association, 2010b; Gacki-Smith, Juarez, Boyett, Hoymeyer, Robinson, & Maclean, 2009; Gerberich et al., 2004; Pich, Hazelton, Sundin, & Kable, 2010), attending physicians (Al-Sawahi et al., 1999; Benham et al., 2008; Kowalenko et al., 2005; Zahid et al., 1999) residents (Benham et al., 2008) and EMS personnel (Grange & Corbett, 2002; Mock, Wrenn, Wright, Eustis, & Slovis, 1998) are all victims of workplace violence. More than a quarter of attending Emergency Medicine (EM) physicians in Michigan reported being victims of a physical assault in the preceding year (Kowalenko et al., 2005; U.S.Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). Approximately 25% of ED nurses experienced violence at least 20 times in the preceding three years (Gacki-Smith et al., 2009).

Workplace violence has been defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC/NIOSH) as “violent acts (including physical assaults and threats of assaults) directed toward persons at work or on duty.” Gates et al. (2006) expanded the definition to include verbal harassment, sexual harassment, verbal threats, and physical assaults. Kowalenko et al. (2005) added “stalking” to the definition. Regardless of the definition, verbal threats and physical assaults have a direct impact on the workers resulting in injury, sadness, fear, anger, job dissatisfaction, and post traumatic stress disorder (Arnetz & Arnetz, 2001; Catlette, 2005; Erickson & Williams-Evans, 2000; Gates & Gillespie, 2008; Gerberich et al., 2004; Gillespie, Gates, Miller, & Howard, 2010; Laposa, Alden, Fullerton, 2003; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2008). In addition, employers are seeing the consequences in the form of medical/psychiatric care costs, decreased productivity, lost days of work, transfers to other departments, quitting, and litigation (Gates et al., in press; Gillespie et al., 2010). Experts agree that scant evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of interventions (American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 2004; American College of Emergency Physicians Board of Directors [ACEP] 2008; Catlette, 2005; Fein et al., 2000; Fernandes et al., 2002; Gates et al., 2011; Mattox, Wright & Bracikowski, 2000; McNamara, Yu, & Kelly, 1997; Nachreiner et al., 2005; Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], 1989; Peek-Asa, Cubbin, Hubbel, 2002; Peek-Asa et al., 2007; Peek-Asa et al., n.d.; Rintoul, Wynaden,& McGowan, 2009; U.S. Department of Labor, 2004; Wassall, 2009).

Importance and Study Goals

Very little specific data exist on who are the victims, who are the perpetrators, what are the circumstances surrounding the violence, and most importantly, what can be done to prevent or control it (Gerberich et al., 2004; May & Grubbs, 2002). In an effort to answer these questions, the authors have initiated a study to develop and test an intervention to reduce violence in EDs. This article reports on the data gathered from the baseline survey of this larger intervention study that is currently underway. Data from ED employees at six hospitals, in two states were collected and analyzed with the following objectives: a) describe the frequency of violence against ED healthcare workers in a cohort of six hospitals; b) identify whether demographic and occupational characteristics of ED healthcare workers are related to violence; and c) identify whether feelings of safety and level of confidence when dealing with workplace violence are related to demographic and occupational characteristics.

Methods

Study Design

Prior to beginning the study, Institutional Review Boards’ (IRB) and hospitals’ approvals were obtained. A cross-sectional design was used to collect data from direct care providers at six hospital EDs; results reported below represent a preliminary report of the baseline survey from a larger intervention study.

Setting

Six hospital EDs participated in this study. Efforts were made to include a variety of hospitals that were representative of most EDs in the U.S.. Two of the participating hospitals were Level I Trauma Centers, two were urban hospitals and two were suburban hospitalsBoth Level 1 Trauma hospitals have separate psychiatric and adult-only EDs. The urban and suburban EDs provide care for all types of patients including children and psychiatric patients.

Selection of Participants

A minimum sample size of 160 participants was needed to obtain sufficient power to test the effectiveness of the intervention study. There were approximately 800 eligible participants at the six hospitals, 300 males and 500 female. A proportional recruitment strategy was developed, based on the total number of eligible employees at each site and in each occupational group. Recruitment flyers were placed in the mailboxes of all physicians (attendings & residents), nurses, patient care assistants, paramedics, physician assistants and nurse practitioners at the six EDs inviting them to participate in the survey study and subsequent intervention study. Flyers were placed in break areas and a representative of the study team met with employees at staff meetings to provide an overview of the study and to answer questions. The first 220 employees who volunteered were screened to ensure they were working at least 20 hours per week in one of the eligible occupational roles at the ED where they were recruited. The first 213 direct care workers who met the inclusion criteria and fit into an open sample category (occupation and ED site) were invited to participate and completed a survey during August and early September 2009.

Method of Measurement

The survey consisted of the following four sections: Demographic and Occupational Questionnaire, Violent Experiences Questionnaire, Safety Scale and Confidence Scale. On the Demographic and Occupational Questionnaire, participants were asked to provide information about their age, gender, race, occupation, patient population where working, previous violence training, and years of experience.

On the Violent Experiences Questionnaire, participants were asked to provide information about the types of violence experienced during the previous six months including number of events, nature of events, perpetrator(s) of events, whether the events resulted in injury or absences, and the frequency of reporting events. Types of violence included verbal harassment, sexual harassment, physical threats, and assaults. Participants were provided definitions to use when answering questions about their violent experiences. The definitions were developed and used in prior research by the researchers (Gates, Mc Queen & Ross, 2006).

Physical assaults include hitting with body part, slapping, kicking, punching, pinching, scratching, biting, pulling hair, hitting with an object, throwing an object, spitting, beating, shooting, stabbing, squeezing, and twisting.

Physical threats include actions, statements, written or non-verbal messages conveying threats of physical injury which were serious enough to unsettle your mind. It includes expressions of intent to inflict pain, injury, or punishment (www.definitions.uslegal.com).

Verbal harassment includes cursing, cussing, yelling at or berating a person in front of another, racial slurs, or humiliating and patronizing actions.

Sexual harassment includes unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature, insulting gestures, whistling, jokes or humor about gender specific traits, offensive pictures, and offensive contact such as patting, pinching, brushing against body, attempted or actual fondling, or kissing.

The Safety Scale (Gates et al., 2006) asked participants to respond to three items asking about their level of agreement (1=strongly disagree to 10=strongly agree for a potential score range of 3 to 30) to statements regarding their feeling of safety while working in the ED, likelihood of being injured by a patient in the next six months, and likelihood of being injured by a visitor in the next six months. The feeling of safety item was reversely-scored to match the direction of the other two items. Higher agreement indicated a higher degree of feeling unsafe.

The Confidence Scale (Gates et al., 2006) is a four-item survey asking participants to identify their level of agreement (1=strongly disagree to 10=strongly agree for a potential score range of 4 to 40) regarding their confidence in dealing with aggressive patients and visitors.

All four instruments were developed and utilized in previous research by the investigators (Gates et al., 2006). The instruments demonstrated good face and content validity, and the internal reliabilities for the Safety Scale and Confidence Scale were high in previous studies (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.9) (Gates, unpublished data). For the current study the alpha for the Safety Scale was 0.75 and 0.95 for the Confidence Scale.

Data Collection and Processing

Survey packets, along with a cover letter were distributed to eligible staff at the six hospital EDs. The participants signed a consent form, completed the surveys and mailed their surveys back to the researchers in a pre-addressed stamped envelope.

Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System for the PC version 9.2 (SAS). Descriptive statistics were computed using frequencies for categorical data and means for continuous variables. Groups representing characteristics of study subjects (job title, area worked in the ED, gender, highest level of education, race/ethnicity, work shift and violence training) were compared using t-tests (for characteristics comprised of 2 groups) and general linear modeling followed by Student-Newman-Keuls adjusted pairwise comparisons (for characteristics comprised of more than 2 groups). Characteristics measured on a continuous scale (length of time worked in the ED, age and hours worked per week) were correlated with the outcome variables using correlations. An alpha-level of 0.05 was used to judge statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of Study Subjects

Two hundred and thirteen participants returned fully completed surveys of which 29% (n=62) were male and 71% (n=151) were female. Eighty-six percent were non-Hispanic white, while 12% represented blacks, Asians, and American Indian/Alaskan natives. The mean age was 37 (range 20 −65), mean number of years of ED experience was 7 (range less than 1 – 35), and mean number of hours worked per week was 37 (range 20 −80). Demographic and workplace characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of employees and employers (n = 211)

| Participant characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 184 | 86 |

| Black | 12 | 6 |

| Asian | 10 | 5 |

| American Indian/Alaskan native | 1 | 1 |

| Multiple races | 5 | 2 |

| Other | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 62 | 29 |

| Female | 151 | 71 |

|

| ||

| Educational level | ||

| High school or GED | 2 | 1 |

| Some college | 32 | 15 |

| 2-year associate degree | 41 | 19 |

| Baccalaureate degree | 73 | 34 |

| Graduate education/professional degree | 65 | 31 |

|

| ||

| Job title | ||

| Medical doctor | 42 | 20 |

| RN | 118 | 55 |

| LPN | 2 | 1 |

| Physician assistant | 5 | 2 |

| Paramedic | 13 | 6 |

| Patient care assistant/ED technician | 25 | 12 |

| Other | 8 | 4 |

|

| ||

| Primary work shift | ||

| Days | 68 | 32 |

| Evenings | 31 | 15 |

| Nights | 36 | 17 |

| Rotating | 70 | 33 |

| Other | 7 | 3 |

|

| ||

| Violence prevention training | ||

| No | 119 | 56 |

| Yes | 92 | 44 |

|

| ||

| Workplace characteristics | ||

| Location of hospital | ||

| Level I trauma center | 130 | 61 |

| Urban | 44 | 21 |

| Suburban | 38 | 18 |

| Patient population | ||

| Adult only | 68 | 32 |

| General (adult and pediatric) | 133 | 62 |

| Psychiatric only | 12 | 6 |

Violence, Injuries and Reporting

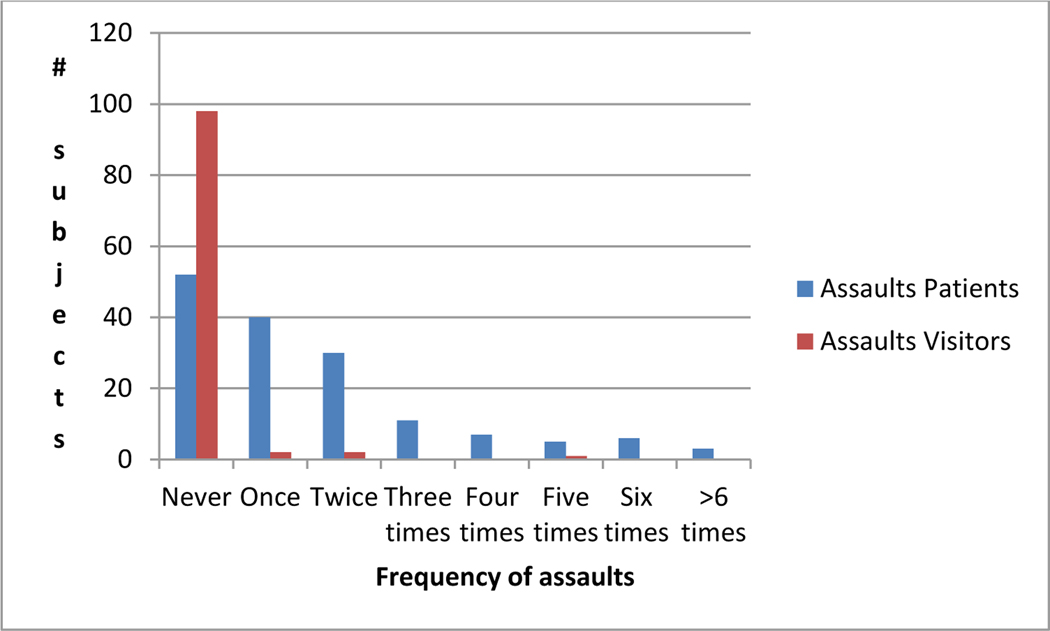

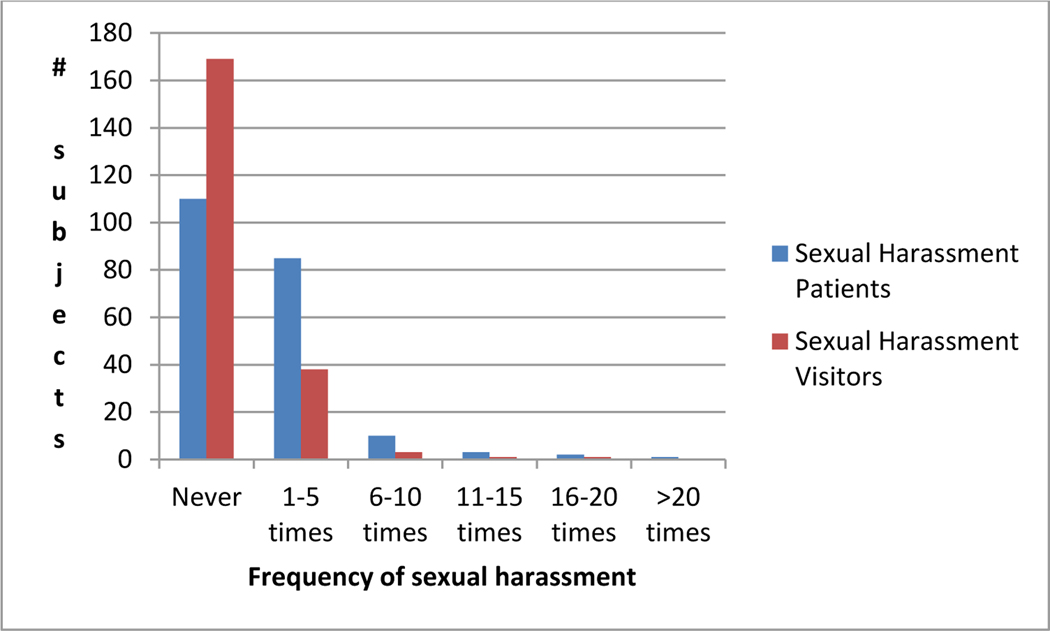

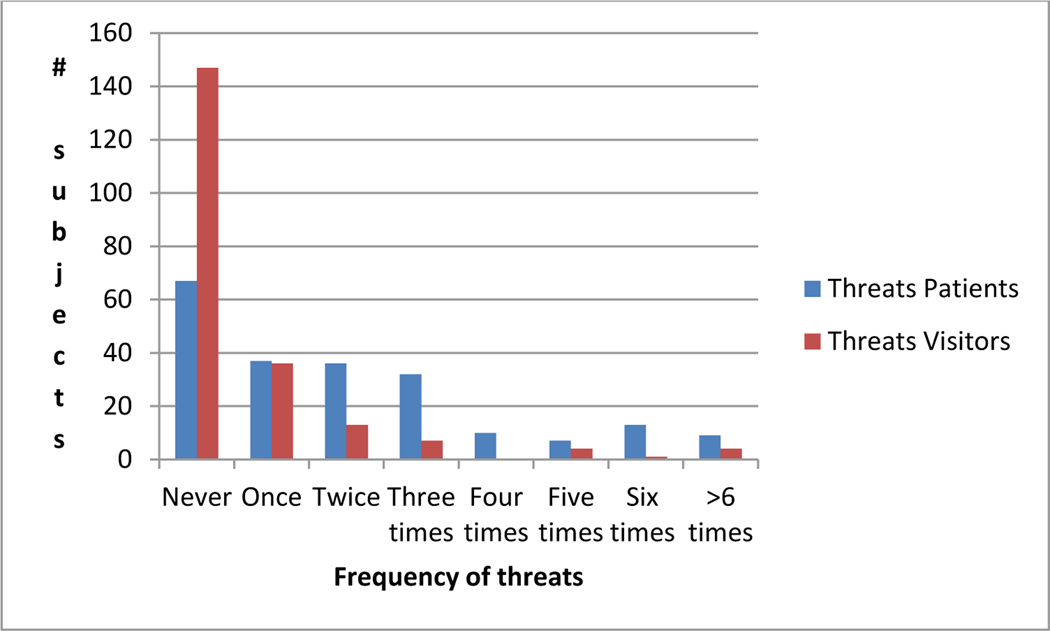

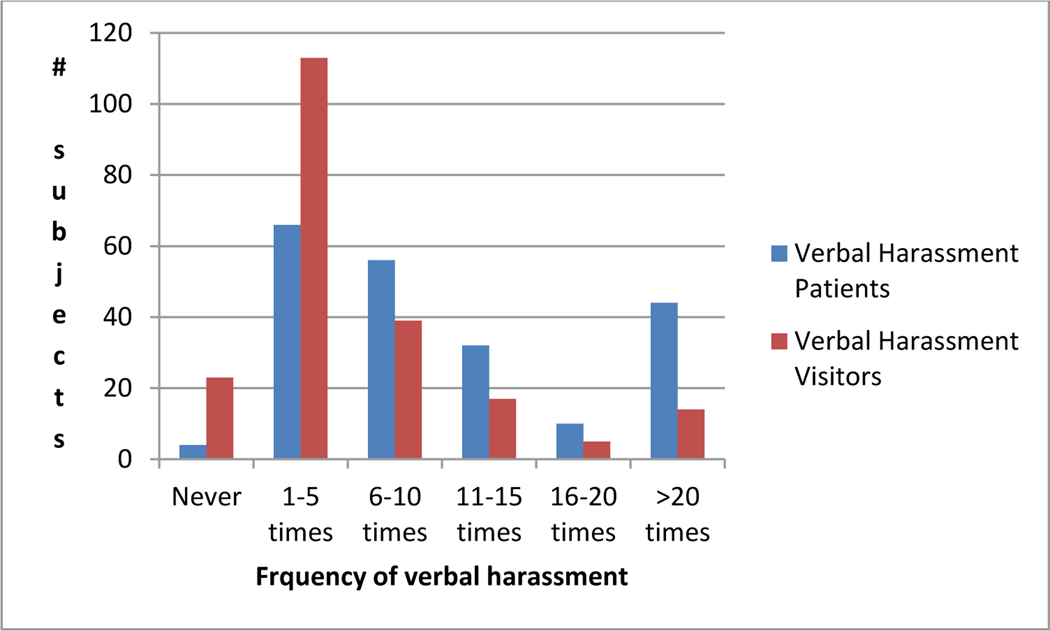

Ninety-eight percent (n= 208) of participants experienced at least one episode of verbal harassment from patients in the previous six months and 88% (n=188) experienced one or more episodes of verbal harassment from visitors. Forty percent (n=86) experienced over 10 episodes of verbal harassment from patients and 17% (n=36) experienced over 10 episodes of verbal harassment from visitors. Forty-seven percent (n=101) experienced at least one episode of sexual harassment from patients and 20 percent (n=43) experienced at least one episode of sexual harassment from visitors during the previous six months. Sixty-eight percent (n=144) of participants experienced at least one physical threat from patients and 31% (n= 65) experienced at least one physical threat from visitors. Forty-eight percent (n=102) experienced at least one physical assault from patients and two percent (n=5) experienced at least one physical assault from a visitor. See Figures 1–4 for illustrations of the frequency distributions for assaults and threats. Nine percent (n=18) of the participants responded that they had been injured by a patient assault during the previous six months.

Figure 1.

Number of physical assaults during previous six months (n=211)

Figure 4.

Frequency of sexual harassment during previous six months (n=211)

Participants were asked how frequently they reported the violence that they encountered in the previous six months. Fifty-five percent (n=109) of the participants responded that they never reported the violence, 19% (n=37) responded “seldom”, 14% (n=28) responded “occasionally”, 6% (n=11) responded “often”, and 6% (n=11) responded “always”. When asked if they interacted with a patient or visitor with a weapon during the previous six months, 30% (n=62) responded “yes”, 38% (n=79) responded “no” and 32% (n=67) responded “not sure.” When asked how often they called security to assist them with a patient or visitor only 6% (n=13) responded never. Thirty-three percent (n=72) responded that they called one to three times, 28% (n=80) responded four to six times, and 23% (n=48) responded that they called seven or more times. Females called security more frequently than males (mean=4. 4 versus 3.64).

Demographic and Occupational Characteristics Associated with Violence, Safety, and Confidence

Age, race, shift, educational level, job title, and previous training were not significantly related to the frequency of any type of violence. Females reported a higher frequency of sexual harassment from patients than males (p=0.0001). Sexual harassment was the only category of violence that differed by gender. Employees working in the psychiatric-only ED experienced a greater frequency of physical threats from patients (p<0.05) than those working in the general and adult-only EDs. Employees working at Level I Trauma Center EDs had significantly higher frequency of physical threats (p<0.05).

The mean for the three item Safety Scale was 16.17 (range 3–30; sd 5.78). Females were significantly more likely to report feeling less safe than males (17.00 vs. 14.14; p <0.001). On the survey item “I feel unsafe while working in the ED,” 54% (n=116) agreed with the statement; males had a mean of 5.05 (range 1–10) and females had a mean of 5.77. Sixty-two percent (n=132) of participants agreed with the statement that “they are likely to be injured by a patient in the next year.” Females (mean = 6.37, range 1–10; p<0.05) were more likely to agree with this statement than males (mean=5.06). Although not statistically significant, nurses had higher scores (meaning they felt less safe) on the Safety Scale (mean=17.69) than patient care assistants (mean=15.42), physicians (mean =13.29) and physician assistants and nurse practitioners (mean =11.40). The Safety Scale was inversely related to age (r= −0.21, p=0.002) and length of time working in an ED (r= −0.16; p=0.02), meaning that older employees and employees with more ED experience felt less safe. Race, educational level, patient population, hospital location, shift, and previous violence prevention training were not significantly related to feelings of safety. Safety was positively related (p<0.05) to the frequency of all types of violence perpetrated by patients and visitors; as the frequency of violence increased participants felt less safe.

The mean for the Confidence Scale was 26.91 (range 5– 40, SD=6.64). Males (mean= 31.20, SD=5.36) were significantly (p<0.001) more likely than females (mean = 25.15; SD=6.32) to agree with the four confidence statements regarding their ability to deal with patients and visitors who are verbally or physically violent. This gender difference was especially evident for the survey item that asked about their ability to deal with patients who are physically violent (7.48 vs.5.28; range 1–10; p<0.0001). Race, educational level, job title, patient population, hospital location, ED population, shift, and previous violence prevention training were not related to confidence levels. The Safety Scale and Confidence Scales were related (r=0.24; p<0.001); as employees’ feelings of safety decreased their confidence in dealing with violence also decreased.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. The participants were not randomly selected; thus it is not known whether those that participated are different than those that did not participate in terms of their violent experiences, personal characteristics, and feeling of safety and confidence. In addition, participants were volunteers chosen on a first-come, first served basis; and participants comprised only 26% of the eligible subjects. This relatively low number of participants at each site could skew the results at any one site or for the group as a whole. The data were self-reported and the participant’s recall may not be accurate. However, because the participants were asked to recall experiences over a short time period, the previous six months, recall bias is likely to have been minimal. The fact that the study surveyed a variety of ED providers and hospitals provides support for the universality of the problem in this healthcare setting.

Discussion

The results from this study support other studies that show violence against ED healthcare providers is a prevalent problem. The finding that many ED providers continue to work in these high risk settings without violence prevention training is also consistent with previous research (54% in this cohort) (Gates et al., 2006; Gacki-Smith et al., 2009). Although training was not found to be related to frequency of violence in this study, this should not be construed as evidence that violence prevention training is not needed to prevent and manage violence. The investigators had no way of knowing the content and quality of the training received by those respondents who reported having received such training. Much of the current violence prevention training continues to consist of generic programs that are not tailored to the unique ED setting or to a specific hospital, and primarily focus on self-defense techniques rather than prevention (Gates et al., 2011). Training emphasis needs to focus on early assessment, de-escalation, and early intervention strategies to mitigate increasing aggression.

An important and interesting finding was that there were no gender-based differences in the frequency of violence except for sexual harassment, which might be anticipated. Popular opinion in many healthcare settings suggests that females are at greater risk of physical violence due to their lesser size and strength. This opinion provides the reason for why in many healthcare settings, when there are aggressive patients, male employees are called and often expected to help (Poster & Ryan, 1994). It is also why many employees prefer to have male security officers. This belief may be related to the preponderance of training programs that focus heavily on self-defense or restraining techniques. While some previous research supports the hypothesis that females are at greater risk, other research findings suggest that females may actually be at lower risk of violence (Fisher & Gunnison, 2001; Gacki-Smith et. al, 2009; Goetz, Bloom, Chenell, & Moorhead, 1991; Hatch-Maillette & Scalor, 2002). Possible explanations for these findings include the fact that females use more nonaggressive techniques to de-escalate patients and as stated above, males are often called to intervene with aggressive patients.

The fact that age, race, educational level, and primary work shift were not associated with an increased frequency of violence demonstrates that all healthcare providers working in EDs are at risk for violence. While there were isolated significant difference in reported physical threats based on the ED’s type of population and physical setting in our sample there were no differences in physical assaults, verbal harassment, and sexual harassment among study sites. A recent ENA surveillance study (ENA, 2010c) of ED nurses found that while nurses who worked in urban EDs did report significantly more violence than those working in rural settings, there were no significant differences in rates between urban and suburban settings. In frequent discussions between the authors and healthcare workers, many expressed their beliefs that persons working in suburban EDs do not experience the level of violence as those persons working in urban and Level I Trauma Center EDs. The fact that the frequencies were not significantly different among the occupational groups and ED locations emphasizes the universality of the problem for all ED employees.

Many of the participants did not feel safe while working in the EDs with the majority believing that they will be injured by a patient in the next six months. This was regardless of job title, patient population, hospital location, and shift worked. There are many reasons why ED workers feel at risk of violence including: patients and visitors using drugs and alcohol, patients with psychiatric disorders or dementia, presence of weapons, inherent stressful environment, open access, and the flow of violence from the community into the ED (Gates et al., 2006; Gillespie et al., 2010). In addition, overcrowding and prolonged waiting times at many EDs increase the stress for patients and visitors (Gates et al., 2006). Although females did not experience a higher frequency of physical violence, they felt significantly more unsafe and at risk of injury from violence than males, and felt significantly less confident in their ability to deal with violent patients and visitors. These differences cannot be attributed to occupation as there were no significant differences in feelings of safety or confidence by job title. The lack of confidence and lower feelings of safety probably contributed to the fact that females called security significantly more often than males. Participants who were older and had more ED experience felt less safe than younger and less experienced providers. This surprising finding is in contrast to a commonly held belief that providers feel safer as they became more skilled in dealing with the variety and types of patients who visit EDs. It is possible that over time, healthcare providers become increasingly aware of the dangers of their work setting and believe that efforts to reduce the violence in their settings are either lacking or ineffective.

There are serious consequences related to workplace violence for the employee, the employer, and the patient. For the employee, violence has been associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms which affects the employee’s performance at work (Gates, Fitzwater, & Succop, 2003; Gates et al., in press; Scalora, Bader, & Bornstein, 2007). Feeling unsafe has been found to be associated with decreased job satisfaction, (Gates et al, 2006) which is associated with absenteeism and turnover. ED personnel have specialized skills and characteristics, and thus it is costly when the organization has to recruit and train new hires. Costs related to injuries, worker’s compensation, and lawsuits can be staggering (Gerberich et al., 2004). Nurses who experience stress symptoms after a violent event report that their ability to provide competent and safe care to patients is negatively affected (Gates, Gillespie & Succop 2011; Scalora et al., 2007). Patients and visitors who witness verbal threats or violence in the ED can become frightened and may perceive that the staff is causing the problem. Patients have been known to leave the ED when such incidents occur.

Despite the fact that many employees reported feeling unsafe, the reporting of violent events was low, supporting the results of other studies (Gacki-Smith et.al 2009; Gates, Ross & McQueen, 2006). Healthcare workers need to bring attention to the problem by reporting violence and by having the expectation that they along with their employer have responsibilities for responding to the growing threat of violence in their work setting. It is key that employees participate actively on safety committees in the ED and work with the hospital safety committee to lead efforts to develop violence prevention programs.

Conclusion

Violence is a serious problem that affects all types of EDs and occupational groups. The adverse consequences of verbal and physical violence affect the healthcare workers, the employer and the patients. Although many workers report feeling unsafe at work and lack the confidence in dealing with aggressive patients and visitors, violent event reporting remains low. ED workers need to assume an important role in documenting the occurrence of the violence and collaborate with leadership to develop and test interventions to reduce violence against ED workers.

Figure 2.

Frequency of physical threats during previous six months (n=211)

Figure 3.

Frequency of verbal harassment during previous six months (n=211)

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This research study was supported by Grant 1R01OH009544-01 from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC-NIOSH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC-NIOSH.

Footnotes

Disclosure:

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Donna Gates, University of Cincinnati College of Nursing, Cincinnati, OH.

Gordon Gillespie, University of Cincinnati College of Nursing, Cincinnati, OH.

Terry Kowalenko, University of Michigan College of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Paul Succop, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH.

Maria Sanker, University of Cincinnati College of Nursing, Cincinnati, OH.

Sharon Farra, University of Cincinnati College of Nursing, Cincinnati, OH.

References

- Al-Sahlawi KS, Zahid MA, Shahid AA, Hatim M, & Al-Bader M. (1999). Violence against doctors: A study of violence against doctors in accident and emergency departments. European Journal of Emergency Medicine, 6(4), 301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. (2004). Workplace violence prevention policy statement. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.org/WD/Practice/Docs/Workplace_Violence.pdf.

- American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP). (2008). Protection from physical violence in the emergency department environment policy statement. Retrieved from http://www.acep.org/practres.aspx?id=29654. [DOI] [PubMed]

- American Nurses Association2006 House of Delegates. (2006). Workplace abuse and harassment of nurses. Retrieved from http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/OccupationalandEnvironmental/occupationalhealth/workplaceviolence/ANAResources/WorkplaceAbuseandHarassmentofNurses.aspx.

- Arnetz JE, & Arnetz BB (2001). Violence toward health care staff and possible effects on the quality of patient care. Social Science and Medicine, 52(3), 417–427. doi 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayranci V. (2005). Violence toward health care workers in emergency departments in West Turkey. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 28(3), 361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham M, Tilotson R, Davis SM, & Hobbs GR (2008).Violence in the emergency department: a national survey of emergency medicine residents and attending physicians. Journal of Emergency Medicine. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.emermed.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boz B, Acan K, Ergin A, Erdur B, Kurtulus A, Turkcuer I, & Ergin N. (2006). Violence toward health care workers in emergency departments in Denizili, Turkey. Advances in Therapy, 23(2), 364–369. doi: 10.1007/BF02850142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlette M. (2005). A descriptive study of the perceptions of workplace violence and safety strategies of nurses working in level 1 trauma centers. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 31(6), 519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crilly J, Chaboyer W, & Creedy D, (2004). Violence towards emergency department nurses by patients. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 12(2), 67–73. 10.1016/j.aaen.2003.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control, National Institute of Occupational Saftely and Health. (2002). Violence: occupational hazards in hospitals (NIOSH publication No. 2002–101). Cincinnati: Ohio. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/pdfs/2002-101.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Emergency Nurses Association. (2010a). Position statement: Violence in the emergency care setting. Retrieved from http://www.ena.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Position%20Statements/Violence_in_the_Emergencys_Care_Setting_-_ENA_PS.pdf.

- Emergency Nurses Association. (2010b). White papers: Violence in the emergency care setting. Retrieved from http://www.ena.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Position%20Statements/Violence_in_the_Emergency_Care_Setting_-_ENA_White_Paper.pdf.

- Erickson L, & Williams-Evans SA (2000). Attitudes of emergency nurses regarding patient assaults. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 26(3), 210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein JA, Ginsburg KR, McGrath ME, Shofer FS, Flamma JC, & Datner EM (2000). Violence prevention in the emergency department. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 154(5), 495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes CM, Bouthillette F, Raboud JM, Bullock L, Moore CF, Christensen JM, Way M. (1999). Violence in the emergency department: A survey of health care workers. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 161(10), 1245–1248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes CMB, Raboud JM, Christensen JM, Bouthillette F, Bullock L, Ouellet L, & Moore CF (2002). The effect of an education program on violence in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 39(1), 47–55. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.121202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, & Gunnison E. (2001). Violence in the workplace: gender similarities and differences. Journal of Criminal Justice, 29(2), 145–155. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2352(00)00090-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gacki-Smith J, Juarez AM, Boyett L, Hoymeyer C, Robinson L, & MacLean SL (2009). Violence against nurses working in US emergency departments. Journal of Nursing Administration. 39(7–8), 340–349. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181ae97db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates D. (2004). The epidemic of violence against healthcare workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(8), 649–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates D, Gillespie G, & Succop P. (2011). Violence against nurses and its impact on stress and productivity. Journal of Nursing Economic$, 29(2):59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates D, Gillespie G, Smith C, Rode J, Kowalenko T, & Smith B. (2011) Using action research to plan a violence prevention program for emergency departments. Journal of Emergency Nurses Association, 37(1), 32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates D, Fitzwater E, & Succop P. (2003). Relationships of stressors, strain, and anger to caregiver assaults. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 24(8), 775–793. doi: 10.1080/01612840390228040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates D, Fitzwater E, Telintelo S, Succop P, & Sommers M. (2004). Preventing assaults by nursing home residents: Nursing assistants’ knowledge and confidence–A pilot study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 3(6), 366–370. doi: 10.1016/S1525-8610(04)70084-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates DM, & Gillespie GL (2008). Secondary traumatic stress in nurses who care for traumatized women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 37(2), 243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates DM, Ross CS, & McQueen L. (2006). Violence against emergency department workers. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 31(3), 331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerberich SG, Church TR, McGovern PM, Hansen HE, Nachreiner NM, Geisser MS,…Watt GD. (2004). An epidemiological study of the magnitude and consequences of work related violence: the Minnesota Nurses’ Study. Occupational andEnvironmental Medicine, 61(6), 495–503. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.007294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie GL (2008). Consequences of violence exposures by emergency nurses. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma, 16(4), 409–418. doi: 10.1080/10926770801926583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Miller M, & Howard PK (2010). Violence against healthcare workers in a pediatric emergency department. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 32(1), 68–82. doi: 10.1097/TME.0b013e3181c8b0b4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie GL, Gates DM, & Succop P. (2010). Psychometrics of the Healthcare Productivity Survey. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 32(3), 258–271. doi: 10.1097/TME.0b013e3181e97510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz RR, Bloom JD, Chenell SL, & Moorhead JC (1991). Weapons possession by patients in a university emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 20(1), 8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grange JT, & Corbett SW (2002). Violence against emergency medical services personnel. Prehospital Emergency Care, 6(2), 186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch-Maillette MA, & Scalor MJ (2002). Gender sexual harassment, workplace violence, and risk assessment: Convergence around psychiatric staff’s perceptions of personal safety. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 7(3), 271–291. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(01)00043-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh KL, Duncan SM, Estabrooks CA, Reimer MA, Giovannetti P, Hyndman K, & Acorn S. (2003). Workplace violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Health Policy, 63(3), 311–321. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00142-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge AN, & Marshal AP (2007). Violence and aggression in the emergency department: A critical care perspective. Australian Critical Care, 20(2), 61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard PK, & Gilboy N. (2009). Workplace violence. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 31(2), 94–1000. doi: 10.1097/TME.0b013e3181a34a14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission (2010), Preventing Violence in the Healthcare Setting, Issue 45, Retrieved October 25, 2010 from http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert/sea_45.htm [Google Scholar]

- Kansagra SM, Rao SR, Sullivan AF, Gordon JA, Magid DJ, Kaushal R,…Blumenthal D. (2008). A survey of workplace violence across 65 U.S. emergency departments. Academic Emergency Medicine, 15(12), 1268–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00282.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalenko T, Walters BL, Khare RK, & Compton S. (2005). Workplace violence: a survey of emergency physicians in the state of Michigan. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 46(2), 142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladau SF, & Bendalak Y. (2008). Personnel exposure to violence in hospital EM wards: A routine activity approach. Aggressive Behavior, 34(1), 88–103. doi 10.1002/ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laposa JM, Alden LE, & Fullerton LM (2003). Work stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in ED nurses/personnel. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 29(1), 23–28. doi: 10.1067/men.2003.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattox EA, Wright SW, & Bracikowski AC (2000). Metal detectors in the pediatric emergency department: Patron attitudes and national prevalence. Pediatric Emergency Care, 16(3), 163–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May DD, & Grubbs LM (2002). The extent, nature, and precipitating factors of nurse assault among three groups of registered nurses in a regional medical center. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 28(1), 11–17. doi: 10.1067/men.2002.121835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAneney CM, & Shaw KN (1994). Violence in the pediatric emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 23(6), 1248–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara R, Yu DK, & Kelly JJ (1997). Public perception of safety and metal detectors in an urban emergency department. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 15(1), 40–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhaul KM, & Lipscomb JA (2004). Workplace violence in health care: recognized but not regulated. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 9(3), 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merecz D, Rymanszewska J, Moscicka, Kiejna A, & arosz-Nowak J. (2006). Violence at the workplace—a questionnaire survey of nurses. European Psychiatry, 21(7) 442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock EF, Wrenn KD, Wright SW, Eustis TC, & Slovis CM (1998). Prospective field study of violence in emergency medical service calls. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 32(1), 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachreiner NM, Gerberich SG, McGovern PM, Church TR, Hansen HE, Geisser MS, & Ryan AD (2005). Relation between policies and work related assault: Minnesota Nurses’ Study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(10), 675–681. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.014134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (1989). Safety and health program management guidelines: Issuance of voluntary guidelines. Federal Register# 59:3904–3916. Retrieved from http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=FEDERAL_REGISTER&p_id=12909. [Google Scholar]

- Peek-Asa C, Allareddy V, Valiante D, Blando J, O’Hagan E, Bresnitz E,…Curry J. (n.d.) Workplace violence and prevention in New Jersey hospital emergency departments. Retrieved from http://www.state.nj.us/health/surv/documents/njhospsec_rpt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Peek-Asa C, Casteel C, Allareddy V, Nocera M, Goldmacher S, O’Hagan E,…Harrison R. (2007). Workplace violence prevention programs in hospital emergency departments. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 49(7), 756–763. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318076b7eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek-Asa C, Cubbin L, & Hubbel CK (2002). Violent events and security programs in California emergency departments before and after the 1993 Hospital Security Act. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 28(5), 420–426. doi: 10.1067/men.2002.127567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pich J, Hazelton M, Sundin D,& Kable A. (2010). Patient-related violence against emergency department nurses. Nursing and Health Sciences, 12(2), 268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poster EC & Ryan J. (1994). A multiregional study of nurses’ beliefs and attitudes about work safety and patient assault. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 45(11), 1104–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintoul Y, Wynaden D, & McGowan S. (2009). Managing aggression in the emergency department: Promoting an interdisciplinary approach. International Emergency Nursing, 17(2), 122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalora MJ, Bader SM, & Bornstein BH (2007). A gender –based incidence study of workplace violence in psychiatric and forensic settings. Violence and Victims, 22(4), 449–462. doi: 10.1891/088667007781553982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonowitz JA (1996). Healthcare workers and workplace violence. Occupational Medicine. 11(2), 277–291. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002-101/#5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. (2010, June 3). Preventing violence in the healthcare setting. Sentinel Event Alert. Issue 45. Retrieved from: http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert/sea_45.htm [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2008). Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work, 2007. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/osnr0031.pdf

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2010). Revisions to the 2007 census of fatal occupational injuries (cfoi) Washington, DC: Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/cfoi/cfoi_revised07.pdf [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. (2004). Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social service workers. Retrieved from http://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3148/osha3148.html. [Google Scholar]

- USLegal.com (n.d). Definitions. Retrieved from http://uslegal.com/

- Wassell JT (2009) Workplace violence intervention effectiveness: A systematic literature review. Safety Science, 47(8), 1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2008.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zahid MA, Al-Sahlawi KS, Shahid AA, Hatim M, & Al-Bader M. (1999). Violence against doctors: Effects of violence on doctors working in accident and emergency departments. European Journal of Emergency Medicine, 6(4), 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]