Abstract

Stress-induced release of dynorphins (Dyn) activates kappa opioid receptors (KOR) in serotonergic neurons to produce dysphoria and potentiate drug reward; however, the circuit mechanisms responsible for this effect are not known. In male mice, we found that conditional deletion of KOR from Slc6a4 (SERT)-expressing neurons blocked stress-induced potentiation of cocaine conditioned place preference (CPP). Within the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), two overlapping populations of KOR-expressing neurons: Slc17a8 (VGluT3) and SERT, were distinguished functionally and anatomically. Optogenetic inhibition of these SERT+ neurons potentiated subsequent cocaine CPP, whereas optical inhibition of the VGluT3+ neurons blocked subsequent cocaine CPP. SERT+/VGluT3− expressing neurons were concentrated in the lateral aspect of the DRN. SERT projections from the DRN were observed in the medial nucleus accumbens (mNAc), but VGluT3 projections were not. Optical inhibition of SERT+ neurons produced place aversion, whereas optical stimulation of SERT+ terminals in the mNAc attenuated stress-induced increases in forced swim immobility and subsequent cocaine CPP. KOR neurons projecting to mNAc were confined to the lateral aspect of the DRN, and the principal source of dynorphinergic (Pdyn) afferents in the mNAc was from local neurons. Excision of Pdyn from the mNAc blocked stress-potentiation of cocaine CPP. Prior studies suggested that stress-induced dynorphin release within the mNAc activates KOR to potentiate cocaine preference by a reduction in 5-HT tone. Consistent with this hypothesis, a transient pharmacological blockade of mNAc 5-HT1B receptors potentiated subsequent cocaine CPP. 5-HT1B is known to be expressed on 5-HT terminals in NAc, and 5-HT1B transcript was also detected in Pdyn+, Adora2a+ and ChAT+ (markers for direct pathway, indirect pathway, and cholinergic interneurons, respectively). Following stress exposure, 5-HT1B transcript was selectively elevated in Pdyn+ cells of the mNAc. These findings suggest that Dyn/KOR regulates serotonin activation of 5HT1B receptors within the mNAc and dynamically controls stress response, affect, and drug reward.

Subject terms: Motivation, Cellular neuroscience

Introduction

Stress has profound effects on the risk of substance use disorders and relapse in humans and promotes drug-seeking behaviors in animal models of addiction [1–4]. Animal studies have shown that the endogenous opioid dynorphin (Dyn) and its cognate receptor, the kappa opioid receptor (KOR), are critical to the enhancement of each stage in the progression towards drug addiction, from initial preference, to escalation, and ultimately reinstatement [2, 5–7]. These have been shown to be mediated in part by stress-induced modulatory effects on the serotonin (5-HT) system; however, the contribution of serotonin (5-HT) to hedonic processing remains controversial [8–10]. In humans, polymorphisms in genes encoding dynorphin, KOR, and the serotonin transporter (SERT) have been linked to stress-induced depression and increased risk for addiction [11–14].

Stress-evoked release of neuropeptides including corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and the prodynorphin-derived peptides impinge on affective circuitry to orchestrate changes in both neurophysiological state and observable behavior [15]. CRF-induced Dyn release and KOR activation is required for the dysphoric and anxiogenic properties of stress. Additionally, Dyn action at KOR on dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons is necessary for a stress-induced dysphoric state, which may underlie stress-potentiation of drug-seeking behaviors [15, 16]. KOR activation within serotonergic neurons of the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), which is a hedonic hot spot and primary source of forebrain serotonin, results in somatic hyperpolarization and increases the surface expression of SERT in axon terminals projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) [9, 10, 17, 18]. Together, these findings suggest that stress-induced activation of the Dyn-KOR-5-HT axis reduces serotonin tone in the NAc to increase drug reward in mice.

Direct manipulation of serotonergic neuron activity in DRN via optogenetic and chemogenetic techniques, however, has resulted in conflicting conclusions concerning the role of 5-HT in mediating responses to rewarding, aversive, and stressful stimuli [19–24]. These discrepancies may be due to the genetic and anatomical complexity of the DRN as well as the impact of different assay conditions and event timing on stress and reward processing [25, 26]. In the present study, we resolved a KOR-expressing, serotonergic projection from the lateral aspect of the DRN to the medial NAc (mNAc) that controls 5-HT tone to regulate stress response, aversion, and reward potentiation. We further implicate presynaptic dynorphin and postsynaptic 5-HT1B receptors within the mNAc in mediating these effects.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult male C57BL/6 mice and transgenic strains on C57BL/6 background were group housed with access to food and water ad libitum. All animal procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to US National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Behavior

rFSS, cocaine CPP, and social approach were performed as previously described [1, 27] Optical stimulation during repeated forced swim stress (rFSS): SERTDRN-NAc ChR2 mice were tethered throughout swim sessions and stimulated on day 1 and swims two and four of day 2. DRN inhibition pretreatment: VGluT3DRN or SERTDRN SwiChR groups received optical inhibition for 30 min, followed by cocaine conditioning 30 min later. SERTDRN-NAc terminal excitation during U50488 pretreatment: 1 h prior to cocaine conditioning, mice received U50488 and optical stimulation, terminating 5 min before cocaine administration. 5-HT1B antagonist pretreatments: GR 127935 was infused into the NAc 135 min and/or 75 min prior to cocaine conditioning or social approach.

Histology

Immunohistochemistry and RNAscope were performed as previously reported [28, 29].

Data analysis

The assumption of normal distribution was tested and corrected for when not met. T tests were unpaired, two-tailed. Post-hoc tests were Sidak’s or Dunnett’s T3 where appropriate, with α = 0.05.

Detailed methods are provided in Supplementary Materials.

Results

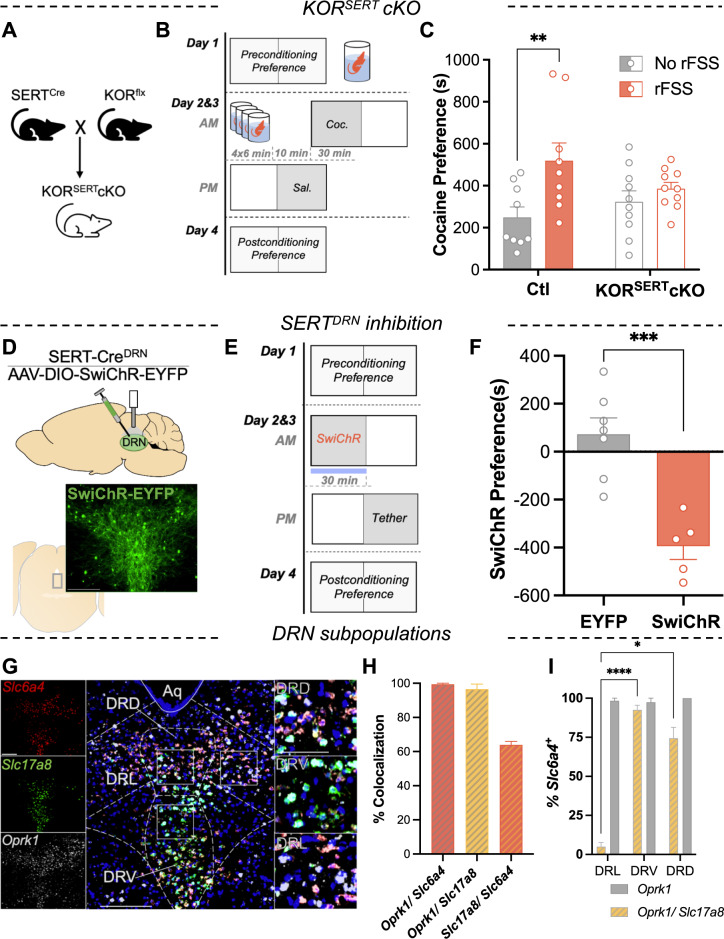

KOR expression in SERT neurons is required for stress potentiation of cocaine reward

Slc6a4-Cre (‘SERT-Cre’) and Oprk1-lox/lox (‘KOR-flx’) mice were crossed as previously described [16], resulting in conditional excision of KOR in SERT+ cells (‘KORSERTcKO’) (Fig. 1A). These mice and their littermate controls were subjected to a modified Porsolt rFSS, which consisted of a 15 min initial swim, followed 22 h later by four 6 min swims that terminated 10 min prior to cocaine conditioning (Fig. 1B). Cocaine place preference of the unstressed KORSERTcKO mice was not significantly different from that of littermate controls (two-way ANOVA; F1,34 = 0.27, P = 0.604), indicating that excision of KOR in SERT-expressing neurons does not regulate basal cocaine preference (Fig. 1C). There was a significant main effect of stress (F1,34 = 8.87, P = 0.005) and a marginal interaction (F1,34 = 3.45, P = 0.072). Comparison of cocaine preference within each genotype revealed a significant effect of stress in controls (Sidak post-hoc, P = 0.004) that was absent in the KORSERT cKO group (P = 0.664) (Fig. 1C). Normalized data revealed that stress increased cocaine preference in controls by more than twofold, significantly more than in KORSERT cKO group (t test, welch-corrected, P = 0.036) (Fig. S1A). These data demonstrate that global deletion of KOR in SERT-expressing neurons blocks stress-induced potentiation of cocaine CPP.

Fig. 1. Serotonin neuron kappa opioid receptors mediate stress potentiation of cocaine reward and can be mimicked by optogenetic inhibition.

A Breeding scheme used to excise KOR gene from SERT-expressing neurons. B Schematic of rFSS potentiation of cocaine CPP protocol. Mice were subjected to rFSS on day 1 and day 2 prior to cocaine conditioning. C Stress potentiation of cocaine preference scores for control and KORSERT cKO mice with or without prior stress (n = 9–10). D Cartoon depicting DRN injection of inhibitory opsin (AAV5-DIO-SwiChR-EYFP) and cannula placement in a SERT-cre mouse. Below: image showing EYFP expression in the DRN. Scale bar = 50 µm. E Schematic of optogenetic CPA protocol. During optogenetic conditioning, the mouse was confined to one chamber where it received opto-inhibition of SERTDRN neurons. F Serotonin inhibition preference scores (postconditioning-preconditioning preference for opto-paired chamber) for control and SwiChR-inhibition conditioned groups (n = 5–7). G Representative image showing expression of transcripts for SERT (Slc6a4), VGluT3 (Slc17a8), and KOR (Oprk1) in the medial DRN. Right insets: higher magnification of rectangular regions showing colocalization in cells of the dorsal, ventral, and lateral aspects of the DRN (DRD, DRV, DRL, respectively). Scale bar = 200, 200, 25 µm. H Quantitation of cells co-expressing two transcripts, expressed as percentage cells in the denominator indicated (n = 3). I Quantitation of Slc6a4+ cells co-expressing Oprk1 or both Oprk1 and Slc17a8 in each subregion, expressed as percentage of Slc6a4+ cells per subregion.

Inhibition of SERT neurons in the DRN is aversive

KOR activation by stress hyperpolarizes serotonergic neurons in the DRN [18], but stress exposure also broadly affects brain physiology. To assess the effect of selective inhibition of DRN neurons, we optogenetically inhibited SERT neurons in the DRN (SERTDRN) by injecting an inhibitory opsin (AAV5-DIO-SwiChR-EYFP) into the DRN of SERT-Cre mice (Fig. 1D). SwiChR is a channelrhodopsin variant that conducts Cl− ions and has been utilized to generate long-term, reversible inhibition, while avoiding photic damage [30, 31]. We conducted a CPP assay by confining the mice to an optically paired chamber during SwiChR-mediated inhibition of SERT neurons in the DRN for 2 days, following and preceding preference tests (Fig. 1E). SwiChR-mediated inhibition of SERT neurons in the DRN induced a robust and significant aversion to the optically paired chamber (t test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1F). These results reflect the necessity of KOR expression within SERT neurons for KOR-mediated aversion [16], and support the conclusion that inhibition of SERTDRN neurons produces place aversion.

KOR is expressed in SERT and VGluT3 subpopulations in the DRN

DRN serotonin neurons are anatomically and phenotypically heterogenous and have been suggested to form functional subsystems regulating diverse stress-sensitive processes [32–36], but the distribution of KOR within DRN serotonin neurons has not been evaluated. RNAscope was used to probe for co-expression of transcripts for KOR (Oprk1), SERT (Slc6a4), and the vesicular glutamate transporter type III (VGluT3DRN; Slc17a8) (Figs. 1G, S1B). SERT and VGluT3-expressing neurons within the DRN comprise largely serotonergic populations that overlap extensively yet may have distinct roles in driving reward-related behaviors [19, 20, 22]. Most Slc6a4 neurons expressed Slc17a8, indicating substantial overlap of SERT and VGluT3 populations in the DRN (Fig. 1H). Oprk1 was present in nearly all Slc17a8+ or Slc6a4+ cells (Fig. 1H). The expression of KOR transcript in the majority of SERT+ and VGluT3+ cells indicates a potential for direct regulation of these subsystems by KOR.

Next, the percentages of SERT+ (Slc6a4+) neurons in each subregion that co-expressed KOR transcript (Oprk1+/Slc6a4+) were determined. The percentage of Slc6a4+ neurons that co-expressed both Oprk1 and Slc7a18 (Oprk1+/Slc17a8+/Slc6a4+) was significantly higher in the dorsal and ventral DRN than in the lateral DRN (DRL), where Slc17a8 was nearly absent (two-way ANOVA; Interaction, F2,8 = 61.1, P < 0.001; Sidak post-hoc P = 0.036, P < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 1I). These data indicate that unlike the majority of SERTDRN neurons, SERT+neurons in the lateral DRN are almost exclusively KOR+/VGluT3−.

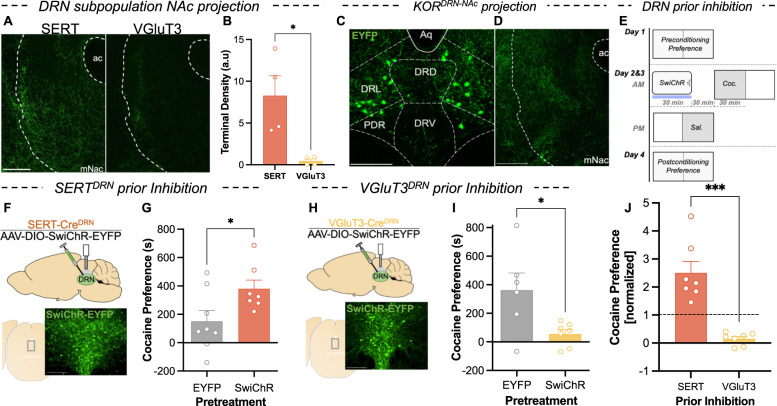

SERT+ projections from the DRN innervate the medial NAc, but VGluT3+ projections neurons do not

To assess the projections of these SERTDRN and VGluT3DRN populations to the NAc, AAV5-DIO-ChR2-EYFP was injected into the DRN of SERT-Cre and VGluT3-Cre mice. Labeled terminals in the mNAc (a region including medial aspect of NAc shell and core) revealed that SERT+ projection terminals in the mNAc were denser than VGluT3+ terminals, which were nearly absent (t test, welch-corrected, P = 0.044) (Fig. 2A, B). In contrast, VGluT3+ and SERT+ terminal density was similar in other regions (Fig. S2A). These data are consistent with previous reports of different projection biases of these populations [19, 32, 37].

Fig. 2. Prior inhibition of DRN serotonin subpopulations with distinct projection bias has divergent effects on cocaine preference.

A NAc terminal expression of EYFP-tagged ChR2 in a SERT-Cre and VGluT3-Cre mouse. Scale bar = 200 µm. B Quantification of terminal density (arbitrary units) in the NAc of SERT-cre and VGluT3-cre mice (n = 4). C Expression of retrogradely delivered EYFP in subregions of central DRN of KOR-Cre mouse. Scale bar = 200 µm. D Expression of EYFP+ terminals in the NAc of KOR-Cre mice. Scale bar = 200 µm. E Schematic showing assay of optogenetic replication of KOR-mediated cocaine CPP potentiation. Mice received optogenetic inhibition of specified DRN subpopulations prior to cocaine conditioning. F Cartoon depicting injection of AAV5-DIO-SwiChR-eYFP into the DRN and placement of cannula above injection site. Below: expression of EYFP-tagged SwiChR in the DRN of a SERT-Cre mouse. Scale bar = 50 µm. G Cocaine preference scores (postconditioning preference-preconditioning preference) for groups subject to control treatment and SERT+ neuron inhibition prior to conditioning (n = 7–8). H Cartoon depicting injection of AAV5-DIO-SwiChR-EYFP into the DRN and placement of the cannula above the injection site. Below: expression of EYFP-tagged SwiChR in the DRN of a VGluT3-Cre mouse. Scale bar = 50 µm. I Cocaine preference scores for groups subjected to control treatment and VGluT3+ neuron inhibition prior to conditioning (n = 6–7). J Comparison of cocaine preference scores (normalized to respective EYFP controls) following inhibition of SERTDRN or VGluT3DRN neurons (n = 7).

NAc-projecting KOR neurons are restricted to the lateral DRN

To confirm that KOR is expressed within the DRN-NAc projection, a retrograde virus (AAVretro-DIO-EYFP) was injected into the NAc of KOR-Cre mice [38]. We observed a population of KOR-expressing, NAc-projecting neurons that was concentrated in the lateral aspect of DRN (Fig. 2C). This indicates that DRN KOR neurons projecting to the NAc define an anatomically segregated subpopulation. To validate these findings, AAV5-DIO-ChR2-EYFP was injected into the DRN of KOR-Cre mice, and examination of the mNAc showed robust terminal expression of the fluorophore (Fig. 2D). Together, these findings demonstrate that KOR is expressed in a subpopulation of DRN neurons that project to the mNAc, indicating a potential for direct regulation of this DRN-NAc projection by Dyn/KOR.

Inhibition of SERT+ neurons in the DRN recapitulates KOR-mediated potentiation of cocaine preference, but inhibition of VGluT3+ neurons does not

Although prior work has demonstrated an association between KOR activation, somatic hyperpolarization of DRN neurons, increased serotonin reuptake, and potentiation of cocaine preference, a causal link between decreased 5-HT tone and increased cocaine preference has not been established. We mimicked previous studies of KOR-agonist induced potentiation of cocaine preference but substituted KOR-agonist administration with optogenetic inhibition of DRN subpopulations (Fig. 2E). SERT-Cre mice received DRN viral injections delivering inhibitory opsin (AAV5-DIO-SwiChR-EYFP) or control (AAV5-DIO-EYFP), and an optical fiber was placed above the site of viral expression (Fig. 2F). These mice received 30 min of SERT+ neuron inhibition that terminated 30 min prior to cocaine conditioning. Comparing cocaine preference scores following SERTDRN SwiChR pretreatment to controls revealed a significant potentiation of subsequent cocaine CPP (t test, welch-corrected, P = 0.037) (Fig. 2G). These findings indicate that prior inhibition of SERT+ neurons in the DRN is sufficient to potentiate cocaine CPP thereafter.

In parallel studies, VGluT3-Cre mice were injected with AAV5-DIO-SwiChR-EYFP or AAV5-DIO-EYFP in the DRN, and an optical fiber was placed above the site of viral expression (Fig. 2H). Surprisingly, VGluT3DRN SwiChR pretreatment significantly attenuated subsequent cocaine preference (t test, welch-corrected, P = 0.050) (Fig. 2I). Normalizing preference scores of the groups receiving pretreatment inhibition of SERT+ or VGluT3+ neurons to their corresponding controls illustrates divergent consequences on subsequent cocaine preference (Fig. 2J). Thus, inhibition of different DRN populations exerted bidirectional control of subsequent cocaine preference, and inhibition of SERTDRN neurons (but not VGluT3DRN neurons) was sufficient to replicate the consequences of stress on subsequent cocaine CPP.

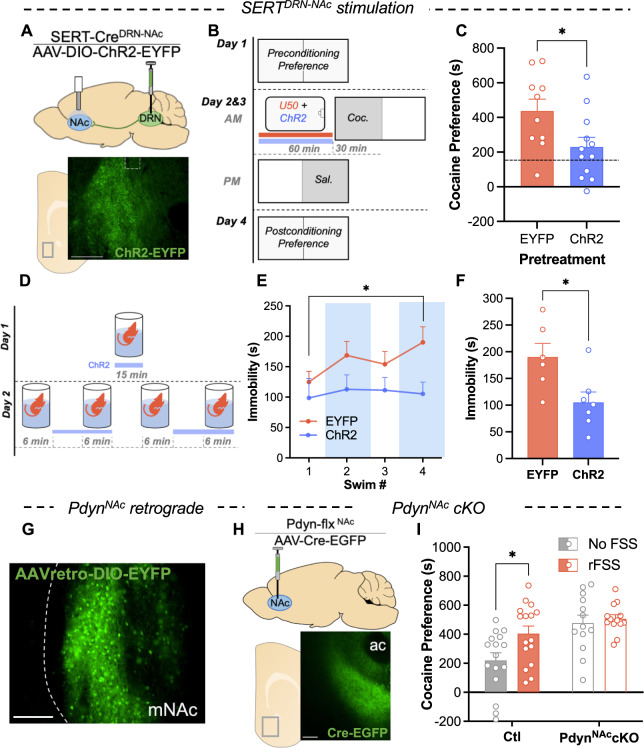

Increased 5-HT tone in the mNAc decreases rFSS immobility and cocaine preference following KOR activation

To probe the hypothesis that a KOR-mediated decrease in serotonin tone within the mNAc may be necessary for potentiation of subsequent cocaine preference, we optogenetically stimulated SERTDRN-NAc terminals during KOR activation. SERT-Cre mice were injected an excitatory opsin (AAV5-DIO-ChR2-EYFP) in the DRN, and a bilateral optical fiber was placed above the mNAc (Fig. 3A). One hour before each cocaine conditioning session, these mice and their controls received pretreatment that included the selective KOR agonist U50488 (5 mg/kg) as well as optical stimulation of SERT+ terminals (to counteract KOR-induced decreases in serotonin tone) that terminated 5 min before cocaine conditioning (Fig. 3B). Concurrent stimulation in the SERTDRN-NAc ChR2 group reduced cocaine preference compared to EYFP controls (t test, P = 0.029). This indicates that increasing serotonin tone in the mNAc during KOR activation decreases subsequent cocaine preference (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Stimulation of DRN-NAc serotonin terminals and PdynNAc cKO regulates cocaine preference.

A Cartoon showing DRN injection of AAV5-DIO-ChR2-EYFP and placement of optical cannula above the NAc in a SERT-Cre mouse. Below: expression of EYFP+ terminals in NAc of SERT-Cre mouse. B Schematic of cocaine CPP with pretreatment of KOR agonist and stimulation of serotonin terminals prior to cocaine conditioning. Prior to each cocaine conditioning session, mice were pretreated with KOR agonist (U50488; 5 mg/kg I.P.) and received concurrent optical stimulation of serotonin terminals in the NAc or control treatment. C Cocaine preference scores of mice receiving KOR agonist prior to cocaine conditioning with or without concurrent ChR2 stimulation of SERT+ terminals in the NAc (Dashed line shows typical unstressed cocaine preference) (n = 10–12). D Schematic of optical stimulation of SERT+ terminals in the NAc during rFSS. E Time immobile during swim bouts on day 2 of rFSS for mice with stimulation of NAc SERT terminals and controls (n = 6–7). F Time immobile during last swim bout of rFSS in E. G Representative images showing expression of retrogradely delivered fluorophore (EYFP) in the NAc of a Pdyn-Cre mouse. Scale bar = 200 µm. H Cartoon showing injection of virus delivering Cre-recombinase (AAV-Cre-EGFP) to the NAc of Pdyn-flx mice. Below: representative image showing expression of AAV-Cre-EGFP in the NAc. I Raw cocaine preference scores for control and PdynNAc cKO mice with or without prior stress (n = 13–16).

Next, SERT+ terminals were stimulated during a rFSS assay to determine if decreased NAc 5-HT is required for rFSS-induced immobility (Fig. 3D). Immobility was analyzed, showing an escalation of immobility in EYFP controls but not in the SERTDRN-NAc ChR2 group (two-way ANOVA; Interaction, F3,33 = 1.050, P = 0.384; Sidak post-hoc, P = 0.0483, P = 0.998, respectively) (Figs. 3E, S3A, S3B). Comparing immobility during the final swim shows that ChR2-stimulated mice spent significantly less time immobile (t test, P = 0.021) (Fig. 3F). These results suggest that stress-induced changes in mNAc serotonergic terminals are required for passive coping and potentiation of subsequent cocaine preference.

Pdyn+ neurons in the NAc are required for stress potentiation of cocaine preference

The role of dynorphin acting on KOR expressed in DRN-NAc projections has been demonstrated by the effects of global prodynorphin gene deletion and local KOR antagonism [1, 8], but the neuronal source of dynorphin responsible for stress-induced potentiation of cocaine CPP is unknown. To identify candidate sources of dynorphin to the NAc, two different retrograde viral constructs (AAVretro-DIO-EYFP or CAV2-DIO-Zsgreen) were injected into the NAc of Pdyn-Cre mice. Examining regions for labeled neurons revealed signal only in the mNAc (Figs. 3G, S3C). Distinct tropisms of these viruses have been documented that may cause either construct to undercount input populations [38]. However, because both show signal exclusively in the mNAc, we conclude that local neurons within the mNAc likely represent the principal source of endogenous dynorphin for this region.

To assess the necessity of these PdynNAc neurons in stress potentiation of cocaine CPP, AAV5-Cre-EGFP or AAV5-EGFP was injected into the NAc of Pdyn-lox/lox (‘Pdyn-flx’) mice to generate ‘PdynNAc cKO’ or ‘Ctl’ mice (Fig. 3H). Examining the NAc of these mice demonstrated viral expression that was confined to the NAc (Fig. 3I). These PdynNAc cKO mice were subjected to a rFSS potentiation of cocaine CPP assay. Cocaine preference scores indicated a main effect of Pdyn excision from the NAc (two-way ANOVA, F1, 54 = 4.73, P = 0.034), indicating that dynorphin within the NAc regulates basal cocaine preference (Fig. 3I). There was also a significant main effect of stress (F1, 54 = 13.1, P = 0.001) but no significant interaction (F1,54 = 2.437, P = 0.124). Stress significantly potentiated cocaine preference in Cre− controls (Sidak post-hoc, P = 0.015) but not in the PdynNAccKOs (P = 0.901). We have routinely observed cocaine preference scores higher than the ~500 s preference in the unstressed PdynNAccKO group, which suggests that the lack of stress potentiation is likely not due to a ceiling effect on expressed preference. To isolate the effect of stress on potentiation of cocaine preference, we normalized rFSS cocaine preference scores in each group to the cocaine preference of their unstressed counterparts (Fig. S3D). This revealed a stress potentiation of cocaine preference of nearly twofold in controls that was absent in PdynNAccKOs. This finding supports a central role of the dynorphinergic population within the NAc in regulation of both basal cocaine preference and stress potentiation of that preference.

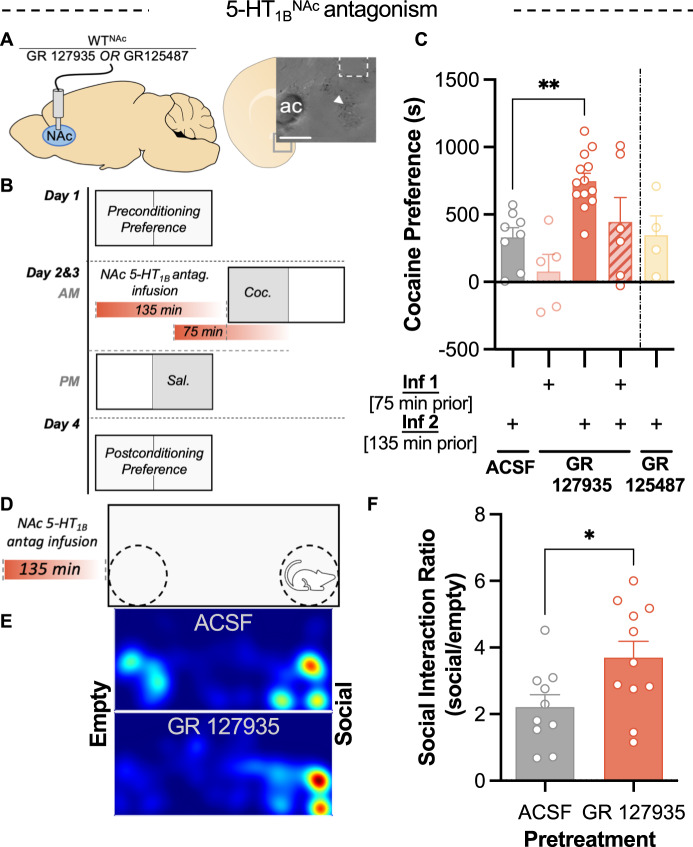

Blockade of mNAc 5-HT1B receptors recapitulates KOR-mediated potentiation of cocaine preference and increases social preference

These findings suggest that a reduction in 5-HT tone in NAc is responsible for stress-induced potentiation of cocaine CPP, but the specific 5-HT receptor type that mediates the consequences of decreased serotonin tone is not known. An especially plausible candidate receptor was 5-HT1B, which is heavily expressed in the nucleus accumbens [39, 40]. 5-HT1B receptors regulate stress-enhancement of psychostimulant effects and have been proposed to mediate a compensatory response to the negative hedonic properties stress [40–42]. To mimic the transient decrease in serotonin at 5-HT1B receptors caused by stress, 5-HT1B antagonist GR 127935 was infused into the NAc of WT mice (Fig. 4A). Histological data measuring pERK-IR (Fig. S4) demonstrated that 5-HT1B receptor blockade was present 75 min, but not 135 min, after GR 127935 infusion. GR 127935 produced a transient decrease in signaling at this receptor (Fig. S3). GR 127935 was infused at 135 min and/or 75 min prior to each cocaine conditioning session (Fig. 4B). Preference scores indicated that only infusion 135 min prior to conditioning resulted in potentiation of cocaine preference (one-way ANOVA, welch-corrected, F4, 10.49 = 7.80, P = 0.004; Dunnett’s T3 post-hoc, P = 0.001) (Fig. 4C). Separately, infusion of a 5-HT4 antagonist prior to cocaine conditioning was tested and failed to potentiate preference, implying that this potentiation is not a general consequence of 5-HTR inhibition (Fig. 4C). GR 127935 failed to potentiate cocaine preference in the group that received a second infusion of antagonist 75 min prior to cocaine conditioning, indicating that this potentiation of cocaine CPP is sensitive to 5-HT1B receptor blockade during cocaine administration (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that a prior decrease in activation of NAc 5-HT1B receptors is sufficient to potentiate subsequent cocaine preference and mimic the effects of rFSS.

Fig. 4. Prior 5-HT1B receptor antagonism in NAc potentiates subsequent cocaine and social preference.

A Cartoon showing implantation of fluid cannula for infusion of 5-HTR antagonists into the NAc of WT mice. (Inset) image showing dye injection (arrow) and damage from cannula confirming placement in medial NAc. Scale bar = 200 µm. B Schematic of cocaine CPP procedure showing pretreatment with NAc infusions of 5-HT1B antagonist (GR 127935) at time points 75 or 135 min prior to cocaine conditioning. C Cocaine place preference scores (postconditioning-preconditioning preference) for mice following infusions of 5-HT1B antagonist GR 127935, 5-HT4 antagonist GR 125487, or ACSF in the NAc at time points 135 min, 75, or 135 + 75 min prior to cocaine conditioning (as depicted in B) (n = 4–13). D Schematic showing pretreatment NAc infusion of 5-HT1B antagonist prior to three-chamber social interaction assay. E Representative heatmaps indicating the distribution of time spent in the social interaction apparatus after infusion of GR 127935 into the NAc 135 min prior and ACSF infusion control. F Social interaction ratio (time spent in social zone/time spent in empty zone) following pretreatment with GR 127935 (n = 10–11).

To assess whether this reward potentiation is specific to cocaine or reflective of a broader change in reward processing the effect of 5-HT1B antagonism on social preference was evaluated. Semi-chronic stressors have been shown to increase social preference [43], but a potential role for 5-HT1B receptors in this process has not been examined. Mice received infusions of GR 127935 or ACSF into the mNAc and 135 min later were assayed for social preference, a behavior regulated NAc 5-HT1B receptors [23]. In this assay, mice could explore an apparatus with an empty, inverted pencil cup in one corner and a pencil cup containing a novel mouse in the opposite corner (Fig. 4D, E). Social interaction scores were significantly greater in mice pretreated with GR 127935 than ACSF (t test, P = 0.028) (Fig. 4F). These findings indicate that a prior blockade of 5-HT1B receptors, utilized here to reflect decreased serotonin tone in the mNAc, induces reward potentiation that generalizes beyond cocaine preference.

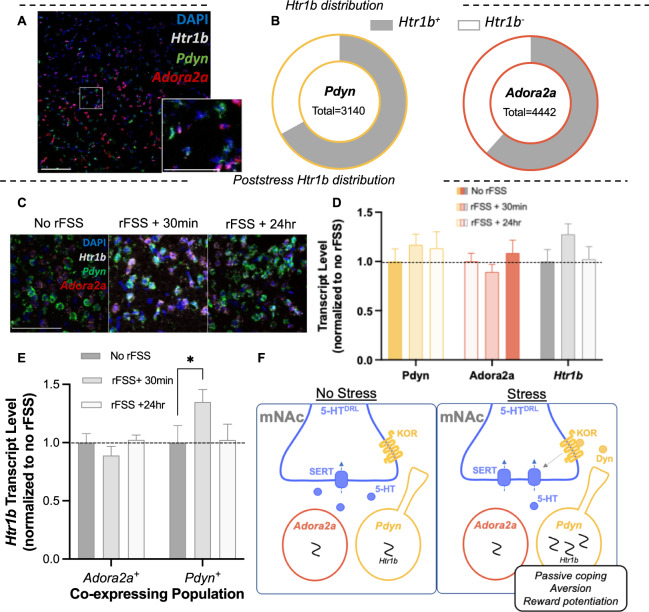

rFSS increases 5-HT1B transcript expression in Pdyn+ neurons in the NAc

Chronic exposure to stress increases 5-HT1B transcript in the NAc, which may represent a compensatory increase in reward sensitivity in response to stress [42, 44, 45]. However, regulation by sub-chronic stress exposure, such as the rFSS used in this study, has not been detected. This may be attributed to low sensitivity of prior techniques or difficulty assessing cell-type specific changes. We used RNAscope to evaluate expression of Htr1b in NAc subpopulations. In unstressed mice, Htr1b colocalized with Pdyn, Adorsa2a, and Chat-expressing cells (Figs. 5A, B and S5). To assess the effects of rFSS on Htr1b expression, brains were dissected 30 min and 24 h after rFSS and stained tissue sections were compared to unstressed controls (Fig. 5C). Total levels of Htr1b, Pdyn, and Adora2a transcript did not change after rFSS (two-way ANOVA, P > 0.05) (Fig. 5D). In contrast, examining the levels of Htr1b in Pdyn and Adora2a subpopulations revealed a significant and selective increase in Htr1b expression in Pdyn+ cells 30 min after stress (two-way ANOVA; F2,36 = 3.53, P = 0.040; Sidak post-hoc, P = 0.046) (Fig. 5E). These results indicate that the sub-chronic stressor (rFSS) which potentiates cocaine CPP induces a transient and selective increase in 5-HT1B transcript in Pdyn+ cells of the mNAc.

Fig. 5. Stress induces a transient and cell-type specific increase in Htr1b expression in the NAc.

A Representative image showing in-situ hybridization labeling Pdyn, Adora2a, and Htr1b transcripts in the medial NAc. Inset: higher magnification of rectangular region. Scale bar = 100, 25 µm (inset). B Proportion of each subpopulation that expresses Htr1b. C Representative images showing colocalization and intensity of labeling of Pdyn, Adora2a, and Htr1b transcripts in the medial NAc after stress. Scale bar = 25 µm. D Quantified total levels of Pdyn, Adora2a, and Htr1b following stress, normalized to no rFSS controls (n = 6–8). E Quantified levels of Htr1b transcripts expressed in Pdyn+ and Adora2a+ cells following stress, normalized to no rFSS controls. F Summary schematic of NAc circuit mediating response to stressors, aversion, and reward potentiation. With exception of SERT, the schematic is simplified to include only entities measured or manipulated in this study. Briefly: Stress activation of KOR by dynorphinergic neurons within the mNAc induces translocation of SERT, which decreases serotonin tone in the mNAc. Decreased serotonin tone in the mNAc is aversive, drives passive stress response, and regulates subsequent cocaine preference. NAc 5-HT1B receptors are critical to the induction and expression of this stress potentiation of cocaine preference. RFSS induces a selective increase 5-HT1B transcript in the Pdyn+ neurons in the NAc, suggesting potential pathway specific regulation of reward processing following stress.

Discussion

The principal findings of the present study provide insight into the mechanisms by which stress impinges on the serotonin system to sensitize animals to subsequent reward. KOR expression within serotonergic neurons and dynorphin expression within the mNAc were critical to rFSS potentiation of cocaine reward. Our results are schematically summarized (Fig. 5F). Temporally precise manipulations of DRN circuitry showed that acute inhibition of DRN serotonin neurons drives negative affect and can potentiate subsequent cocaine preference. Additional experiments indicated that KOR-induced decreases in serotonin within the NAc regulate both behavioral coping and cocaine preference. We isolated the effect of decreased serotonin tone at the 5-HT1B receptor by transient blockade of 5-HT1B receptors, which was sufficient to recapitulate the potentiation of cocaine preference observed following KOR activation (Fig. 5F). Lastly, we show that rFSS selectively increases expression of 5-HT1B transcript in Pdyn+ neurons (Fig. 5F). Together, this evidence details a potential Dyn-KOR-5-HT-5HT1B axis contained within the mNAc, in which rFSS provokes a transient decrease of serotonin tone that is central to passive coping, aversion, and increased cocaine preference.

Stressful events in humans and non-human primates are associated with increased drug preference and drug taking that may facilitate the transition to habitual use [46–49]. RFSS is a sub-chronic, inescapable stressor that induces robust physiological and behavioral responses, and we employed it in this study to model the effects of a stressful event on cocaine preference [1, 50]. Similar effects have been observed following other stressors, including nicotine withdrawal and social defeat [9, 17, 51]. The discrete nature of stress exposure in rFSS allowed for precise control of the timing of stress relative to cocaine administration and facilitated interrogation of the effects of stress on subsequent cocaine preference.

Stress and KOR activation potentiate cocaine preference through interactions at serotonin terminals in the ventral striatum, but the circuitry involved has not been fully characterized [1, 5, 8, 17]. We indicate that the KOR-expressing neurons in the lateral DRN that project to the mNAc and Pdyn-expressing neurons located within the mNAc likely regulate stress potentiation of cocaine preference. Retrograde tracing of dynorphin inputs to the mNAc revealed only inputs from the mNAc itself, implying that Pdyn+ neurons may provide the sole source of dynorphin to this region. This indicates that in addition to a critical role in stress-potentiation of cocaine preference, Pdyn+ neurons in the NAc may also regulate other behaviors that are dependent on KOR activation in the NAc, including escalation of drug taking, learned helplessness, and pain-induced negative affect and anhedonia [6, 20, 52–55].

We observed robust aversion to SERTDRN neuronal inhibition in the present study. Although place preference is not a direct measure of affect, this finding supports theories of serotonin function that assert a central role of decreased serotonin tone in negative affect [10, 26]. Together with data indicating the necessity of KORSERT in stress potentiation of cocaine CPP, these results suggest that a decrease in serotonin tone may mediate stress-induced dysphoria, thereby increasing subsequent preference for cocaine [9, 49]. During stress potentiation of cocaine preference, stress likely decreases NAc serotonin prior to cocaine administration, but this effect is unlikely persistent, as cocaine inhibition of SERT function dramatically increases NAc serotonin tone [9, 56]. Thus, temporally precise manipulation of DRN serotonin was crucial to evaluating our central hypothesis that a prior stress-induced decrease in serotonin tone drives subsequent increased sensitivity to drug reward. Our findings support this model and may support a general framework by which KOR and 5-HT-mediated dysphoria increases the relative impact of reward on affect.

Recently, an integral role of SERTDRN neurons in regulating response to stress and reward has begun to come into focus, but how SERTDRN neurons mediate the impact of stress on responses to natural and drug reward remains opaque [25, 32, 34, 57]. We isolated the potential role of decreased serotonin tone in stress potentiation of cocaine preference first by selective inhibition of SERTDRN neurons prior to cocaine conditioning and demonstrated this that a prior reduction in serotonin was sufficient to potentiate subsequent cocaine preference. Surprisingly, we found that inhibition of VGluT3DRN neurons, which overlap extensively with SERTDRN, strongly attenuated subsequent cocaine preference. We note different baseline cocaine preferences in these genotypes, which may be attributed to strain differences and inter-wave assay variability. However, these differences are likely not responsible for the observed effects of neuronal inhibition, in part because the observed effects were large and controls and experimental mice were assayed concurrently. These findings further demonstrate that the DRN is a critical regulator of reward behavior, and we reason that these divergent effects may be mediated by the non-overlapping fraction of these DRN populations (i.e., SERT+/VGluT3− neurons drive reward potentiation) and their projections. The population of overlapping VGluT3+/SERT+DRN neurons project to a myriad of target regions, including the lateral hypothalamus, ventral tegmental area and many aspects of the cortex [33]. Based on our DRN in-situ hybridization and projection tracing studies, we suggest the population responsible for stress potentiation of cocaine preference may comprise SERT+/VGluT3−/KOR+neurons of lateral DRN that project to the mNAc. This subregion is anatomically segregated, highly responsive to stress, and separate from parts of the DRN known to innervate other regions involved in reward processing [35, 58].

Historically, the effect of stress on serotonin in the NAc has been controversial, with evidence for increases, decreases, and no effect on serotonin tone [9, 59–62]. While we did not directly measure 5-HT tone, this study leveraged the neurochemically and anatomically precise nature of terminal optogenetic stimulation during stress to manipulate the SERTDRN-NAc projection and indicate that a decrease in 5-HT tone within the mNAc promotes stress-induced immobility. These findings contribute to recent findings of parallel DRN serotonin subsystems innervating distinct targets to regulate reward and response to stressors [32, 34]. Thus, while serotonin tone within the mNAc is a critical regulator of passive coping behavior, serotonin tone in other regions may also regulate passive coping, possibly in coordination with the DRN-mNAc projection.

In this study, we examined potential contributions of the 5-HT1B receptor to stress potentiation of reward. 5-HT1B receptors are Gi-coupled GPCRs that inhibit neurotransmitter release and have been implicated in regulating the response to stressors and psychostimulants [40]. However, the direction of these effects is dependent on brain region, involvement of autoreceptors or heteroreceptors, and stage of addiction cycle [63–66]. In the mNAc, transient overexpression of 5-HT1B heteroreceptors during mild stress enhances stress-induced potentiation of the psychomotor effects of amphetamine [40]. We observed that transient antagonism of 5-HT1B receptors in the NAc was sufficient to recapitulate potentiation of cocaine preference induced by stress or decreased serotonin tone. Transient antagonism of NAc 5-HT1B receptors also potentiated social preference, a behavior mediated by NAc 5-HT1B receptors, which also recapitulates reports of stress-induced increases in social preference [23, 43]. At the behavioral level, these increases in drug and social reward seeking may represent an attempt to buffer the negative hedonic effects of stress [27, 67]. At the receptor level, these data suggest that 5-HT1B in the NAc acts as a critical signal transducer, sensing a decrease in 5-HT tone and initiating postsynaptic consequences that result in potentiation of reward. Our findings also indicate that the mechanism by which decreased 5-HT1B activation results in potentiation of subsequent cocaine reward may generalize to processing of other rewarding stimuli, including natural rewards. Lastly, we showed that potentiation of cocaine preference induced by transient prior blockade of NAc 5-HT1B was attenuated by an additional antagonist infusion that blocked 5-HT1B receptors during cocaine conditioning. These findings indicate that the 5-HT1B receptor is not only involved in initiating reward potentiation but is involved in mediating the expression of increased reward as well.

5-HT1B transcript is highly expressed in the NAc, and prior work indicates that chronic exposure to stressors or psychostimulants may regulate its expression within the accumbens to increase reward sensitivity [42, 44]. Colocalization of the 5-HT1B transcript (Htr1b) with markers of the direct pathway (Pdyn), indirect pathway (Adora2a), and cholinergic interneurons (Chat) showed uniform distribution across these cell types, indicating that serotonin actions through 5-HT1B receptors may regulate these populations in concert to modulate processing in the NAc. Following stress, 5-HT1B mRNA increased within Pdyn+, but not Adora2a+ neurons, suggesting that stress selectively increases the expression of 5-HT1B transcript in cells of the direct pathway. Whether this increase in transcript is accompanied by an increase in functional receptors remains to be tested. Prior work has also shown that overexpression of 5-HT1B receptors in the NAc sensitizes rats to the hedonic properties of cocaine [39, 68], which intimates that stress-induced increases of postsynaptic 5-HT1B receptors in direct pathway neurons may mediate stress potentiation of reward. The attenuation of potentiated cocaine preference by 5-HT1B receptor blockade during cocaine conditioning supports this conclusion.

Chronic stress induces hedonic and motivational deficits that contribute to depression-like behavior, but sub-chronic stress can provoke coping responses. This coping response may include a proadaptive hedonic allostasis that increases sensitivity to reward and is reflected by increases in mNAc 5-HT1B expression. We indicate this coping response is maladaptive in the context of drug exposure, resulting in increased drug preference and enhanced addiction risk. Broadly, we hypothesize that the proadaptive compensatory adaptations that underlie reward potentiation are exhausted following chronic stress exposure. Collapse of adaptations in this circuit and others may be expected to decrease reward sensitivity. While our data are consistent with this interpretation, future work is required to assess the behavioral and cellular tenets of this theory. In human studies, polymorphisms of the 5-HT1B receptor have been associated with major depression and substance use disorder [69–71], and receptor binding studies show altered 5-HT1B binding in the NAc of subjects with major depression and alcohol dependence [72, 73]. Such findings suggest a central role of NAc 5-HT1B receptors in regulation of affect and substance use, but a potential connection to the Dyn/KOR system and stress potentiation of addiction risk has not been previously evaluated. The insights gleaned from this study support a functional Dyn-KOR-5-HT-5-HT1B axis in which decreased 5-HT is a central regulator of drug preference, affect, and response to stressors. Future studies will be required to directly evaluate the consequences and kinetics of the stress and dynorphin-mediated effects on functional 5-HT1B receptors and evaluate the therapeutic potential of this dynamic circuit.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Larry Zweifel, Sarah Ross, and Richard Palmiter for providing reagents; Dr. Kevin Coffey for assistance with MATLAB scripts used in RNAscope analysis; Zeena Rivera for genotyping assistance; and the WM Keck Microscopy Center for microscopy support.

Author contributions

HMF, PS, CN, RT, and AA conducted the experiments. HMF, PS, RT analyzed the results. All of the authors contributed to the design of the experiments. HMF and CC wrote the manuscript. JFN, PS, and BBL provided editorial comments.

Funding

This research was supported by USPHS grants P50-MH106428 (CC), T32GM007750 (HMF), R01-DA030074 (CC), R01 DA041356 (JN), and S10 OD016240 (Keck Center).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/23/2021

The Supplementary Information has been corrected.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41386-021-01178-0.

References

- 1.McLaughlin JP, Marton-Popovici M, Chavkin C. κ opioid receptor antagonism and prodynorphin gene disruption block stress-induced behavioral responses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5674–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05674.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redila VA, Chavkin C. Stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking is mediated by the kappa opioid system. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:59–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1122-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N. Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105–30. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantsch JR, Vranjkovic O, Twining RC, Gasser PJ, McReynolds JR, Blacktop JM. Neurobiological mechanisms that contribute to stress-related cocaine use. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaughlin JP, Land BB, Li S, Pintar JE, Chavkin C. Prior activation of kappa opioid receptors by U50,488 mimics repeated forced swim stress to potentiate cocaine place preference conditioning. Neuropsychopharmacol Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31:787–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitfield TW, Schlosburg JE, Wee S, Gould A, George O, Grant Y, et al. Opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell mediate escalation of methamphetamine intake. J Neurosci. 2015;35:4296–305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1978-13.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JS, Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal S. Biased signalling: from simple switches to allosteric microprocessors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:243–60. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Land BB, Bruchas MR, Schattauer S, Giardino WJ, Aita M, Messinger D, et al. Activation of the kappa opioid receptor in the dorsal raphe nucleus mediates the aversive effects of stress and reinstates drug seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19168–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910705106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schindler AG, Messinger DI, Smith JS, Shankar H, Gustin RM, Schattauer SS, et al. Stress produces aversion and potentiates cocaine reward by releasing endogenous dynorphins in the ventral striatum to locally stimulate serotonin reuptake. J Neurosci. 2012;32:17582–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3220-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo M, Zhou J, Liu Z. Reward processing by the dorsal raphe nucleus: 5-HT and beyond. Learn Mem. 2015;22:452–60. doi: 10.1101/lm.037317.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuanyuan J, Rui S, hua T, Jingjing C, Cuola D, Yuhui S, et al. Genetic association analyses and meta-analysis of Dynorphin-Kappa Opioid system potential functional variants with heroin dependence. Neurosci Lett. 2018;685:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerra G, Leonardi C, Cortese E, D’Amore A, Lucchini A, Strepparola G, et al. Human Kappa opioid receptor gene (OPRK1) polymorphism is associated with opiate addiction. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2018;144B:771–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuferov V, Levran O, Proudnikov D, Nielsen DA, Kreek MJ. Search for genetic markers and functional variants involved in the development of opiate and cocaine addiction, and treatment. Ann N. Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:184–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Land BB, Bruchas MR, Lemos JC, Xu M, Melief EJ, Chavkin C. The dysphoric component of stress is encoded by activation of the dynorphin-opioid system. J Neurosci. 2008;28:407–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4458-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehrich JM, Messinger DI, Knakal CR, Kuhar JR, Schattauer SS, Bruchas MR, et al. Kappa opioid receptor-induced aversion requires p38 MAPK activation in VTA dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2015;35:12917–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2444-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruchas MR, Schindler AG, Shankar H, Messinger DI, Miyatake M, Land BB, et al. Selective p38α MAPK deletion in serotonergic neurons produces stress resilience in models of depression and addiction. Neuron. 2011;71:498–511. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemos JC, Roth CA, Messinger DI, Gill HK, Phillips PEM, Chavkin C. Repeated stress dysregulates-opioid receptor signaling in the dorsal raphe through a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2012;32:12325–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2053-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDevitt RA, Tiran-Cappello A, Shen H, Balderas I, Britt JP, Marino RAM, et al. Serotonergic versus nonserotonergic dorsal raphe projection neurons: differential participation in reward circuitry. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1857–69. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z, Zhou J, Li Y, Hu F, Lu Y, Ma M, et al. Dorsal raphe neurons signal reward through 5-HT and glutamate. Neuron. 2014;81:1360–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi J, Zhang S, Wang H-L, Wang H, de Jesus Aceves Buendia J, Hoffman AF, et al. A glutamatergic reward input from the dorsal raphe to ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5390. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H-L, Zhang S, Qi J, Wang H, Cachope R, Mejias-Aponte CA, et al. Dorsal raphe dual serotonin-glutamate neurons drive reward by establishing excitatory synapses on VTA mesoaccumbens dopamine neurons. Cell Rep. 2019;26:1128–1142.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh JJ, Christoffel DJ, Heifets BD, Ben-Dor GA, Selimbeyoglu A, Hung LW, et al. 5-HT release in nucleus accumbens rescues social deficits in mouse autism model. Nature. 2018;560:589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0416-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcinkiewcz CA, Mazzone CM, D’Agostino G, Halladay LR, Hardaway JA, DiBerto JF, et al. Serotonin engages an anxiety and fear-promoting circuit in the extended amygdala., Serotonin engages an anxiety and fear-promoting circuit in the extended amygdala. Nat Nat. 2016;537:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature19318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong W, Li Y, Feng Q, Luo M. Learning and stress shape the reward response patterns of serotonin neurons. J Neurosci. 2017;37:8863–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1181-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen JY, Amoroso MW, Uchida N. Serotonergic neurons signal reward and punishment on multiple timescales. ELife. 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Steger JS, Land BB, Lemos JC, Chavkin C, Phillips PEM. Insidious transmission of a stress-related neuroadaptation. Front Behav Neurosci. 2020;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Bruchas MR, Xu M, Chavkin C. Repeated swim-stress induces kappa opioid-mediated activation of ERK1/2 MAPK. Neuroreport. 2008;19:1417–22. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32830dd655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lesiak AJ, Coffey K, Cohen JH, Liang KJ, Chavkin C, Neumaier JF. Sequencing the serotonergic neuron translatome reveals a new role for Fkbp5 in stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. 10.1038/s41380-020-0750-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Berndt A, Lee SY, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K. Structure-guided transformation of channelrhodopsin into a light-activated chloride channel. Science. 2014;344:420–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1252367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen C-C, Lu J, Yang R, Ding JB, Zuo Y. Selective activation of parvalbumin interneurons prevents stress-induced synapse loss and perceptual defects. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1614. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren J, Friedmann D, Xiong J, Liu CD, Ferguson BR, Weerakkody T, et al. Anatomically defined and functionally distinct dorsal raphe serotonin sub-systems. Cell. 2018. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Ren J, Isakova A, Friedmann D, Zeng J, Grutzner SM, Pun A, et al. Single-cell transcriptomes and whole-brain projections of serotonin neurons in the mouse dorsal and median raphe nuclei. ELife. 2019;8:e49424. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teissier A, Chemiakine A, Inbar B, Bagchi S, Ray RS, Palmiter RD, et al. Activity of raphé serotonergic neurons controls emotional behaviors. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1965–76. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valentino RJ, Lucki I, Van Bockstaele E. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the dorsal raphe nucleus: linking stress coping and addiction. Brain Res. 2010;1314C:29. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okaty BW, Sturrock N, Escobedo Lozoya Y, Chang Y, Senft RA, Lyon KA, et al. A single-cell transcriptomic and anatomic atlas of mouse dorsal raphe Pet1 neurons. ELife. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Brown P, Molliver ME. Dual serotonin (5-HT) projections to the nucleus accumbens core and shell: relation of the 5-HT transporter to amphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1952–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01952.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tervo DGR, Hwang B-Y, Viswanathan S, Gaj T, Lavzin M, Ritola KD, et al. A designer AAV variant permits efficient retrograde access to projection neurons. Neuron. 2016;92:372–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neumaier JF, Vincow ES, Arvanitogiannis A, Wise RA, Carlezon WA. Elevated expression of 5-HT1B receptors in nucleus accumbens efferents sensitizes animals to cocaine. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10856–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10856.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferguson SM, Sandygren NA, Neumaier JF. Pairing mild stress with increased serotonin-1B receptor expression in the nucleus accumbens increases susceptibility to amphetamine. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1576–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carhart-Harris RL, Nutt DJ. Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:1091–120. doi: 10.1177/0269881117725915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furay AR, McDevitt RA, Miczek KA, Neumaier JF. 5-HT1B mRNA expression after chronic social stress. Behav Brain Res. 2011;224:350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor GT. Fear and affiliation in domesticated male rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1981;95:685–93. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoplight BJ, Vincow ES, Neumaier JF. Cocaine increases 5-HT1B mRNA in rat nucleus accumbens shell neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:444–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neumaier JF, McDevitt RA, Polis IY, Parsons LH. Acquisition of and withdrawal from cocaine self-administration regulates 5-HT mRNA expression in rat striatum. J Neurochem. 2009;111:217–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morgan D, Grant KA, Gage HD, Mach RH, Kaplan JR, Prioleau O, et al. Social dominance in monkeys: dopamine D 2 receptors and cocaine self-administration. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:169–74. doi: 10.1038/nn798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoyland MA, Latendresse SJ. Stressful life events influence transitions among latent classes of alcohol use. Psychol Addict Behav J Soc Psychol Addict Behav. 2018;32:727–37. doi: 10.1037/adb0000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newcomb MD, Harlow LL. Life events and substance use among adolescents: mediating effects of perceived loss of control and meaninglessness in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:564–77. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruchas MR, Land BB, Chavkin C. The dynorphin/kappa opioid system as a modulator of stress-induced and pro-addictive behaviors. Brain Res. 2010;1314:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porsolt RD, Le Pichon M, Jalfre M. Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature. 1977;266:730–2. doi: 10.1038/266730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLaughlin JP, Li S, Valdez J, Chavkin TA, Chavkin C. Social defeat stress-induced behavioral responses are mediated by the endogenous kappa opioid system. Neuropsychopharmacol Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31:1241–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nealey KA, Smith AW, Davis SM, Smith DG, Walker BM. κ-opioid receptors are implicated in the increased potency of intra-accumbens nalmefene in ethanol-dependent rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shirayama Y, Ishida H, Iwata M, Hazama G, Kawahara R, Duman RS. Stress increases dynorphin immunoreactivity in limbic brain regions and dynorphin antagonism produces antidepressant-like effects. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1258–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newton SS, Thome J, Wallace TL, Shirayama Y, Schlesinger L, Sakai N, et al. Inhibition of cAMP response element-binding protein or dynorphin in the nucleus accumbens produces an antidepressant-like effect. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10883–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10883.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Massaly N, Copits BA, Wilson-Poe AR, Hipólito L, Markovic T, Yoon HJ, et al. Pain-induced negative affect is mediated via recruitment of the nucleus accumbens kappa opioid system. Neuron. 2019;102:564–573.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andrews CM, Lucki I. Effects of cocaine on extracellular dopamine and serotonin levels in the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacol. 2001;155:221–9. doi: 10.1007/s002130100704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seo C, Guru A, Jin M, Ito B, Sleezer BJ, Ho Y-Y, et al. Intense threat switches dorsal raphe serotonin neurons to a paradoxical operational mode. Science. 2019;363:538–42. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bang SJ, Commons KG. Forebrain GABAergic projections from the dorsal raphe nucleus identified by using GAD67–GFP knock-in mice. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:4157–67. doi: 10.1002/cne.23146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirby LG, Allen AR, Lucki I. Regional differences in the effects of forced swimming on extracellular levels of 5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. Brain Res. 1995;682:189–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00349-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Price ML, Kirby LG, Valentino RJ, Lucki I. Evidence for corticotropin-releasing factor regulation of serotonin in the lateral septum during acute swim stress: adaptation produced by repeated swimming. Psychopharmacol. 2002;162:406–14. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De La Garza R, Mahoney JJ. A distinct neurochemical profile in WKY rats at baseline and in response to acute stress: implications for animal models of anxiety and depression. Brain Res. 2004;1021:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carlezon WA, Béguin C, DiNieri JA, Baumann MH, Richards MR, Todtenkopf MS, et al. Depressive-like effects of the κ-opioid receptor agonist salvinorin a on behavior and neurochemistry in rats. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2006;316:440–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Filip M, Papla I, Nowak E, Jungersmith K, Przegaliński E. Effects of serotonin (5-HT) 1B receptor ligands, microinjected into accumbens subregions, on cocaine discrimination in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharm. 2002;366:226–34. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0583-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fletcher PJ, Azampanah A, Korth KM. Activation of 5-HT1B receptors in the nucleus accumbens reduces self-administration of amphetamine on a progressive ratio schedule. Pharm Biochem Behav. 2002;71:717–25. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pentkowski NS, Acosta JI, Browning JR, Hamilton EC, Neisewander JL. Stimulation of 5-HT1B receptors enhances cocaine reinforcement yet reduces cocaine-seeking behavior. Addict Biol. 2009;14:419–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pentkowski NS, Harder BG, Brunwasser SJ, Bastle RM, Peartree NA, Yanamandra K, et al. Pharmacological evidence for an abstinence-induced switch in 5-HT 1B receptor modulation of cocaine self-administration and cocaine-seeking behavior. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5:168–76. doi: 10.1021/cn400155t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ditzen B, Heinrichs M. Psychobiology of social support: the social dimension of stress buffering. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2014;32:149–62. doi: 10.3233/RNN-139008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barot SK, Ferguson SM, Neumaier JF. 5-HT1B receptors in nucleus accumbens efferents enhance both rewarding and aversive effects of cocaine. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3125–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun H-FS, Chang Y-T, Fann CS-J, Chang C-J, Chen Y-H, Hsu Y-P, et al. Association study of novel human serotonin 5-HT1B polymorphisms with alcohol dependence in Taiwanese Han. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:896–901. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang Y, Oquendo MA, Harkavy Friedman JM, Greenhill LL, Brodsky B, Malone KM, et al. Substance abuse disorder and major depression are associated with the human 5-HT 1B receptor gene (HTR1B) G861C polymorphism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:163–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cao J, LaRocque E, Li D. Associations of the 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 1B gene (HTR1B) with alcohol, cocaine, and heroin abuse. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162:169–76. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murrough JW, Neumeister A. The serotonin 1B receptor: a new target for depression therapeutics? Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:714–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu J, Henry S, Gallezot J-D, Ropchan J, Neumaier JF, Potenza MN, et al. Serotonin 1B receptor imaging in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:800–3. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.