Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) can progress to cardiovascular complications which are linked to higher in-hospital mortality rates. Infective endocarditis (IE) can develop in patients with recent COVID-19 infections, however, characterization of IE following COVID-19 infection has been lacking. To better characterize this disease, we performed a systematic review with descriptive analysis of the clinical features and outcomes of these patients.

Methods

Our search was conducted in 8 databases for all published reports of probable or definite IE in patients with a prior COVID-19 confirmed diagnosis. After ensuring an appropriate inclusion of the articles, we extracted data related to clinical characteristics, modified duke criteria, microbiology, outcomes, and procedures.

Results

Searches generated a total of 323 published reports, and 20 articles met our inclusion criteria. The mean age of patients was 52.2 ± 16.9 years and 76.2% were males. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in 8 (38.1%) patients, Enterococcus faecalis in 3 patients (14.3%) and Streptococcus mitis/oralis in 2 (9.5%) patients. The mean time interval between COVID-19 and IE diagnoses was 16.7 ± 15 days. Six (28.6%) patients required critical care due to IE, 7 patients (33.3%) underwent IE-related cardiac surgery and 5 patients (23.8%) died during their IE hospitalization.

Conclusions

Our systematic review provides a profile of clinical features and outcomes of patients with a prior COVID-19 infection diagnosis who subsequently developed IE. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, it is essential that clinicians appreciate the possibility of IE as a unique complication of COVID-19 infection.

Key Indexing Terms: Infective endocarditis, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Outcomes

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has affected over 220,000,000 individuals globally by September of 2021.1 COVID-19 usually presents with signs and symptoms of upper and/or lower respiratory tract infection2, 3, 4, 5 which may rapidly progress to severe respiratory failure. Cardiovascular complications have also been described in these patients and can develop either during or after the course of this illness.6 Cardiac complications include myocarditis7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, stress cardiomyopathy13, myocardial infarction14, heart failure exacerbations15 and arrhythmias16, all associated with a higher risk of in-hospital mortality.17 In addition, case reports of probable or definite infective endocarditis (IE) have also been reported in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. Therefore, the current systematic review was conducted to provide a descriptive analysis of the clinical features and outcomes of patients with IE and recent COVID-19.

Methods

Data sources and searches

The literature was searched by a medical librarian (DJG) for studies including both IE and COVID-19 infection. Search strategies were created using a combination of keywords and standardized index terms as well as run against COVID-19 database filters in Ovid Embase, Ovid Medline, and PubMed. Searches were conducted on August 30, 2021 in Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1991+), Ovid Embase (1974+), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS, 1982+), Ovid Medline (1946+ including epub ahead of print, in-process & other non-indexed citations), PubMed (1946+), Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO, 1997+), Scopus (1823+), and Web of Science Core Collection (Science Citation Index Expanded 1975+ & Emerging Sources Citation Index 2015+). No limits were applied yielding a total of 323 citations. Deduplication was performed in Covidence18 leaving 178 citations (Table 1 ). Full search strategies are provided in the supplementary appendix.

Table 1.

Literature search.

| Databases & Registers | # of initial hits |

|---|---|

| Central (clinical trial register) | 0 |

| Embase | 138 |

| LILACS | 1 |

| Ovid Medline | 32 |

| PubMed | 63 |

| SciELO | 0 |

| Scopus | 49 |

| Web of Science | 40 |

| Totals | 323 |

| Duplicates Removed | 145 |

| Final total | 178 |

The search strategy and study protocol were developed following the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews. This study was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42021275412.

Study selection

To capture all cases in pertinent studies, the inclusion criteria included: (1) positive COVID-19 diagnosis confirmed by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction or serologic antibiotic testing; and (2) modified Duke criteria19 for definite or possible infective endocarditis were used to define IE cases; case reports and series in English or Spanish language from September 1, 2019 through August 30, 2021 were selected. This date range was selected to include all case reports regarding the initiation of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) patients without a diagnosis of COVID-19 or definite/possible IE; (2) patients with non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis; and (3) patients without laboratory confirmation that COVID-19 preceded an IE diagnosis.

We planned to exclude patients with a time interval greater than 3 months between COVID-19 and IE diagnosis, but no cases with this interval were detected in our systematic review.

Data extraction

Following the initial search in 8 databases, references were uploaded to the platform Covidence and shared with all investigators. Titles and abstracts screening were performed independently by two reviewers (JAQM, JRH) and then conflicts were addressed by more senior investigators (DCD, LMB). Full text of the remaining articles was evaluated independently by the same two reviewers to ensure appropriateness for inclusion, if a disagreement presented it was discussed and resolved among them. Finally, reviewers proceeded to data extraction from the selected articles. Thirteen of the corresponding authors from the selected studies were contacted via e-mail for missing information, seven responded back.

Data synthesis and analysis

A collection form was prepared and then used, it included geographical information, clinical characteristics, modified duke criteria, microbiology, outcomes, laboratories, and procedures. Categorical variables of interest were summarized by totaling across the different case reports and reported as proportions with percentages. Continuous variables were similarly averaged across all case reports and presented as mean ± standard deviation and/or median with interquartile range (IQR). The pooled data were then presented in tables.

Results

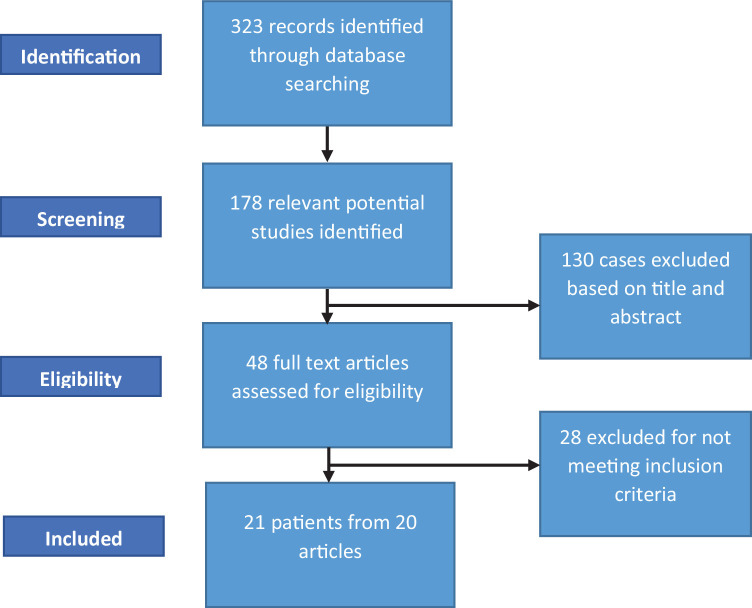

Twenty-one cases from 20 publications that satisfied inclusion criteria were identified20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 (Fig. 1 ). There were 8 cases in the United States, 7 in Europe (Italy 3, Spain 2, United Kingdom 1 and Greece 1), 3 in the Middle East (Iran, Morocco, Tunisia), 2 in South America (Brazil and Ecuador), and 1 in Asia (Indonesia). Mean age of patients was 52.2 ± 16.9 years, median 77 within an (IQR) of 37 to 68.5, and 76.2% were males. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen and was isolated in 8 (38.1%) patients, 2 of which were methicillin resistant. Enterococcus faecalis was isolated in 3 patients (14.3%) and Streptococcus mitis/oralis was identified in 2 (9.5%) patients. The mean and median time interval between COVID-19 and IE diagnoses was 16.7 ± 15 days and 10 days (IQR: 7.75 to 20.75) respectively.

Fig. 1.

Selection flow chart demonstrating abstract and article screening.

Six (28.6%) patients required critical care due to IE, 7 patients (33.3%) underwent IE-related cardiac surgery and 5 patients (23.8%) died during their IE hospitalization (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Cases of patients with COVID-19 who developed IE.

| Author | Age | Gender | Location | Microorganism | IE-related ICU care | IE-related cardiac surgery | In-hospital mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Castro20 | 34 | Female | United States | Haemophilus parainfluenzae | Yes | ||

| Amir21 | 61 | Male | Indonesia | Negative (recent prior antibiotics) | |||

| Alizadeh22 | 50 | Male | United Kingdom | MSSA | Yes | ||

| Alizadehasl23 | 24 | Male | Iran | MSSA | |||

| Kumanayaka24 | 38 | Male | United States | Streptococcus mitis/oralis | |||

| Regazzoni25 | 70 | Male | Italy | MSSA | |||

| Lowell26 | 59 | Female | United States | Streptococcus agalactiae | Yes | ||

| Kraiem27 | 60 | Male | Tunisia | Enterococcus faecalis | |||

| Benmalek28 | 76 | Female | Morocco | Coagulase-negative staphylococcus | Yes | ||

| Choudhury29 | 73 | Male | United States | MSSA | |||

| Joshi30 | 28 | Male | United States | Serratia marcescens | Yes | Yes | |

| Hayes 31 | 38 | Male | United States | Streptococcus mitis/oralis | Yes | Yes | |

| Spinoni32 | 57 | Male | Italy | MRSA | |||

| Dias33 | 36 | N/A | Brazil | MRSA | Yes | ||

| De Vivo34 | 77 | Male | Italy | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Yes | ||

| Velez-Paez35 | 53 | Male | Ecuador | Staphylococcus hominis | Yes | ||

| Sanders 36 | 38 | Male | United States | Enterococcus faecalis | Yes | ||

| Schizas37 | 59 | Male | Greece | Staphylococcus lugdunensis | Yes | Yes | |

| Ramos-Martinez38 | 68 | Female | Spain | Enterococcus faecalis | Yes | Yes | |

| Ramos-Martinez38 | 67 | Male | Spain | MSSA | Yes | Yes | |

| Brotherton39 | 31 | Male | United States | MSSA |

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; ICU, intensive care unit; N/A, not available; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Clinical characteristics are presented in Table 3 . The most common symptoms were fever in 18 (85.7%) patients, cough in 10 (47.6%), dyspnea in 9 (42.9%) and fatigue in 6 (28.6%). Mean temperature (37.9 ± 1.2), and oxygen saturation (89.3 ± 10.2) were reported in 10 cases; mean heart rate (109 ± 21.6), systolic (109.4 ± 20.3) and diastolic (58.1 ± 14.5) blood pressures in 9 cases; and mean respiratory rate (23.4 ± 4.4) in 5 cases.

Table 3.

IE-related clinical characteristics of patients with previous COVID-19.

| Symptoms | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fever | 18 (85.7) | |

| Cough | 10 (47.6) | |

| Dyspnea | 9 (42.9) | |

| Fatigue | 6 (28.6) | |

| Chills | 4 (19.0) | |

| Altered mental status | 4 (19.0) | |

| Anorexia | 3 (14.3) | |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (14.3) | |

| Myalgia | 2 (9.5) | |

| Urinary symptoms | 2 (9.5) | |

| Arthritis | 2 (9.5) | |

| Diarrhea | 1 (4.8) | |

| Chest pain/ discomfort | 1 (4.8) | |

| Nocturnal hyperhidrosis | 1 (4.8) | |

| Nausea | 1 (4.8) | |

| Headaches | 1 (4.8) | |

| Postnasal drip | 1 (4.8) | |

| Low back pain | 1 (4.8) | |

| Hyperreflexia | 1 (4.8) | |

| Weight loss | 1 (4.8) | |

| Vital signs (# of cases reported) | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) |

| Temperature, Celsius (10) | 37.9 ± 1.2 | 38.0 (37.3–38.8) |

| Saturation of oxygen, % (10) | 89.3 ± 10.2 | 92.5 (86.5–96.3) |

| Heart rate (9) | 109.0 ± 21.6 | 100 (95.5–123.0) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg (9) | 109.4 ± 20.3 | 110 (90.0–129.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg (9) | 58.1 ± 14.5 | 58.0 (46.0–69.5) |

| Respiratory rate (5) | 23.4 ± 4.4 | 24.0 (19.0–27.5) |

| Endocarditis clinical findings | N (%) | |

| Systolic murmur | 5 (23.8) | |

| Vascular phenomena | 2 (9.5) | |

| Diastolic murmur | 1 (4.8) | |

| Osler nodes | 1 (4.8) | |

| Splinter hemorrhages | 1 (4.8) | |

| Predisposing conditions | N (%) | |

| Immunosuppression | 7 (33.3) | |

| Intravenous catheter | 5 (23.8) | |

| Chronic hemodialysis | 3 (14.3) | |

| Urinary catheter | 2 (9.5) | |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 2 (9.5) | |

| Injection drug user | 1 (4.8) | |

| Prosthetic valve | 1 (4.8) | |

| Cardiovascular implanted electronic device | 1 (4.8) | |

| Comorbidities | N (%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 5 (23.8) | |

| Hypertension | 3 (14.3) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (14.3) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (4.8) | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1 (4.8) | |

| Obesity | 1 (4.8) | |

| Chronic osteomyelitis | 1 (4.8) | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | 1 (4.8) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (4.8) | |

| Gestation | 1 (4.8) | |

| Smoking history | 1 (4.8) |

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; IQR, interquartile range.

Cardiac auscultation detected 1 diastolic and 5 systolic murmurs (3 of them holosystolic). One patient presented with Osler nodes and splinter hemorrhages on the index finger and two others had embolic phenomena.

The most prevalent comorbidities were diabetes mellitus type 2 (5 [23.8%] patients), hypertension (3 [14.3%] patients), and atrial fibrillation (3, [14.3%] patients).

Among predisposing conditions of IE, 7 (33.3%) patients were receiving immunosuppressant medications for COVID-19 prior to their IE diagnosis, including methylprednisolone, dexamethasone, and tocilizumab; 5 (23.8%) patients had indwelling central venous catheters; 3 (14.3%) other patients were on chronic hemodialysis; one patient each had injection drug use, rheumatic heart disease, prosthetic valve, or cardiovascular implantable electronic device.

Echocardiographic findings

Seventeen (81.0%) of the 21 patients had a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and 12 (57.1%) of them had a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) performed (Table 4 ). TTE findings included vegetations involving the mitral valve (4 patients, 23.5%), aortic valve (4 patients, 23.5%), tricuspid valve (3 patients, 17.6) and a cardiovascular implanted electronic device lead (1 patient, 5.9%). Out of the 12 reported vegetations, 6 (50%) had a dimension > 10 mm. Mitral regurgitation was present in 4 patients (23.5%), of which 2 were mild (11.8%), 1 moderate, and 1 severe. Tricuspid regurgitation was present in 3 patients (17.6%), of which 1 was moderate and 2 severe. Aortic regurgitation was diagnosed in 5 patients (29.4%), of which 3 were graded as moderate and 2 as severe.

Table 4.

Echocardiographic findings in patients with COVID-19 who subsequently developed IE.

| Echocardiographic finding | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| TTE | 17 |

| Mitral vegetation | 4 |

| Aortic vegetation | 4 |

| Tricuspid vegetation | 3 |

| Mitral + tricuspid vegetation | 1 |

| Lead vegetation | 1 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 4 |

| Mild | 2 |

| Moderate | 1 |

| Severe | 1 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 3 |

| Moderate | 1 |

| Severe | 2 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 5 |

| Moderate | 3 |

| Severe | 2 |

| TEE | 12 |

| Mitral vegetation | 4 |

| Aortic vegetation | 5 |

| Tricuspid vegetation | 2 |

| Mitral + tricuspid vegetation | 1 |

| Lead vegetation | 1 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 2 |

| Mild | 1 |

| Moderate | 1 |

| Severe aortic regurgitation | 4 |

| Paravalvular aortic abscess | 1 |

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram.

TEE detected vegetations involving the aortic valve in 5 (41.7%) patients, mitral valve in 4 (33.3%) patients, tricuspid valve in 2 (16.7%) patients and the lead of a cardiac implanted electronic device in 1 patient (8.3%). A vegetation size > 10 mm was found in 2 patients. Severe mitral regurgitation was present in 4 (33.3%) patients. Tricuspid regurgitation was seen in 2 (16.7%) patients and was mild in one case and moderate the other. One patient had paravalvular abscess.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the only registered systematic review published that provides a clinical profile of IE in patients with recent COVID-19. Such an analysis is critical recognizing the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and its cardiovascular complications, infectious and non-infectious in nature.

Several unique clinical features have characterized IE following a COVID-19 infection diagnosis. First, the mean age of our cohort was 52.2 years, considerably younger than most patients with non-IDU-related IE in the US and Europe; in these cohorts, the age is usually > 60 years.40 , 41 Reported median age data also reflected a younger cohort in our systematic review as compared to that in North America; 57 years (IQR: 37 to 68.5) vs. 63 years (IQR: 48 to 75).42 Second, the predominance (76%) of males is more than expected in these other cohorts. Third, respiratory complaints were commonplace and were likely due to recent COVID-19 infection.

The time between COVID-19 infection and IE diagnoses deserves additional address for several reasons. First, IE is an uncommon syndrome43, in contrast to COVID-191; thus, the likelihood that fever will trigger an early consideration of IE as a cause is low. Second, due to the infectivity of COVID-19, invasive diagnostic procedures, in particular TEE, have been avoided to reduce potential healthcare-associated spread of COVID-19.44 , 45 This concern was likely representative of the limited (57%) use of TEE in our cohort. S. aureus, as the predominant IE pathogen in our cohort, could have also impacted the time interval between the two syndrome diagnoses. Due to its well-recognized virulence, IE due to this pathogen is likely to be acute in presentation.

Whether mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 infection can predispose to IE remain undefined. It is tempting to speculate, however, that there may be at least two independent mechanisms that could be operative in the predilection of IE. Based on an animal model of infection46, sentinel findings highlighted the possibility that not only damaged endothelium can predispose to IE caused by S. aureus, but a second independent mechanism may involve inflammation of the cardiac valve with expression of surface structures to enhance bacterial adhesion. It is clear from prior COVID-19-related investigations that vascular endothelial surfaces can be impacted by endotheliitis47; whether the same is true for valvular endothelium seems plausible. Obviously, more work is needed to better define IE pathogenesis in the setting of recent COVID-19 infection. Moreover, some patients had predisposing conditions associated with the development of IE which could have been important in IE pathogenesis

Of note, only one blood culture-negative endocarditis case was included in our cohort and was likely due to recent antibiotic exposure. Antibiotic use in cases of COVID-19, particularly early in the pandemic, has secured extensive review and stewardship concerns regarding selection of antibiotic resistance, increased risk of drug adverse events, and financial costs. These concerns must be balanced, however, with the need to treat healthcare-related infections among COVID-19 patients, particularly those with prolonged hospital stays and critical care exposure.48, 49, 50

Five (23.8%) patients died during their in-hospital stay for IE management, which is a rate reflected, based on previously published cohorts not related to recent COVID-19 infection.51, 52, 53 Considering the potential impact of recent COVID-19 infection on mortality, a higher mortality rate may have been expected. Of course, there is risk of publication bias among case reports included in the current systematic review with publication of only successfully treated patients.

Limitations

Despite performing a search which included multiple library databases in our systematic review, a limited number of cases were identified. As outlined above, several factors could limit the number of IE cases being detected. Also, the retrospective nature of the systematic review resulted in a lack of clinical data to confirm COVID-19 infection in some cases which were excluded. Moreover, the lack of detailed clinical data prevented inclusion of IE cases per modified Duke criteria. This study may have been limited by reporting bias; nevertheless, we contacted the corresponding authors from selected publications for missing information. Finally, due to the millions of COVID-19 cases that have occurred globally, an argument that the small number of reported IE cases were not associated with COVID-19 infection. Based on factors including healthcare exposure, predominant pathogen, possible pathogenesis consideration, and immunosuppression therapy, it seems reasonable to consider a possible link of IE with recent COVID-19 infection.

Conclusions

This systematic review provides the first descriptive analysis of the clinical features and outcomes of 21 patients with IE and prior COVID-19. Due to the ongoing pandemic, it is expected that additional IE cases will occur, and clinicians should be aware of this life-threatening complication.

Addendum

We recently learned of an unregistered systematic review with fewer cases that was published in the journal entitled “American Journal of Medical Case Reports” (10.12691/ajmcr-9-7-11). We recognize that due to the unprecedented interest generated by the current pandemic, all aspects of COVD-19-related presentations are both more likely to be published and in a more rapid manner, therefore increasing the risk of publication overlap.

Author contribution

J.A.Q.M.: Conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing; J.R.H.: Conceptualization, data collection, Writing - review & editing; M.M.: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing; D.J.G.: Conceptualization, literature search; D.C.D: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing; L.M.B.: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Larry M. Baddour, M.D. reports UpToDate, royalty payments (authorship duties); Boston Scientific, consultant duties; Botanix Pharmaceuticals, consulting duties; Roivant Sciences Inc., consultant duties. None of the other authors had disclosures.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement

External funding was not used for this systematic review.

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful for the philanthropic support provided by a gift from Eva and Gene Lane (L.M.B.), which was paramount in our work to advance the science of cardiovascular infections, which has been an ongoing focus of investigation at Mayo Clinic for over 60 years.

Patient consent statement

This study does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2022.02.005.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 7 September 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m ; 2021. Accessed September 10, 2021.

- 2.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. (London, England) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. (London, England) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bansal M. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(3):247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu H., Ma F., Wei X., Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis treated with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J. 2020;42(2):206. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried J.A., Ramasubbu K., Bhatt R., et al. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;141(23):1930–1936. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inciardi R.M., Lupi L., Zaccone G., et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):819–824. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim I.C., Kim J.Y., Kim H.A., Han S. COVID-19-related myocarditis in a 21-year-old female patient. Eur Heart J. 2020:ehaa288. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavazzi G., Pellegrini C., Maurelli M., et al. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(5):911–915. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J.H., Liu Y.X., Yuan J., et al. First case of COVID-19 complicated with fulminant myocarditis: a case report and insights. Infection. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01424-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh S., Desai R., Gandhi Z., et al. Takotsubo syndrome in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review of published cases. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00557-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong N., Cai J., Zhou Y., Liu J., Li F. End-Stage heart failure with COVID-19. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(6):515–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatla A., Mayer M.M., Adusumalli S., et al. COVID-19 and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):1439–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B., et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covidence systematic review software. Available at: www.covidence.org. 2021 Accessed September 21, 2021.

- 19.Li J.S., Sexton D.J., Mick N., et al. Proposed modifications to the duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(4):633–638. doi: 10.1086/313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Castro A., Abu-Hishmeh M., El Husseini I., Paul L. Haemophilus parainfluenzae endocarditis with multiple cerebral emboli in a pregnant woman with coronavirus. ID Cases. 2019;18 doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00593. e00593-e00593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amir M., Djaharuddin I., Sudharsono A., Ramadany S. COVID-19 concomitant with infective endocarditis: a case report and review of management. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alizadeh K., Bucke D., Khan S. Complex case of COVID-19 and infective endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(8) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-242205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alizadehasl A., Salehi P., Roudbari S., Peighambari MM. Infectious endocarditis of the prosthetic mitral valve after COVID-19 infection. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(48):4604. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumanayaka D., Mutyala M., Reddy D.V., Slim J. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection as a risk factor for infective endocarditis. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e14813. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regazzoni V., Loffi M., Garini A., Danzi GB. Glucocorticoid-induced bacterial endocarditis in COVID-19 pneumonia something to be concerned about? Circ J. 2020;84(10):1887. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-20-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowell A., Ramirez G.A., Patel Y., Azari B. COVID-19 infection predisposing endocarditis complicated by the challenges of patient care in a pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(18):1986. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraiem S., Amor H.H. Bi-valvular endocarditis occurring 2 months after COVID-19 infection. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;39:37. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.39.37.29540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benmalek R., Mechal H., Choukrallah H., et al. Bacterial co-infections and superinfections in COVID-19: a case report of right heart infective endocarditis and literature review. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35:40. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23577. (Suppl 2)40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choudhury I., Han H., Manthani K., Gandhi S., Dabhi R. COVID-19 as a possible cause of functional exhaustion of CD4 and CD8 T-cells and persistent cause of methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Cureus. 2020;12(7):e9000. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9000. e9000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joshi G.S., Patel H., Sanchez-Garcia W., et al. Unicuspid aortic valve concomitant with infective endocarditis and severe aortic regurgitation in a patient with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(18):2026. 2026. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes D.E., Rhee D.W., Hisamoto K., et al. Two cases of acute endocarditis misdiagnosed as COVID-19 infection. Echocardiography. 2021;38(5):798–804. doi: 10.1111/echo.15021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spinoni E.G., Degiovanni A., Della Corte F., Patti G. Infective endocarditis complicating COVID-19 pneumonia: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2020;4(6):1–5. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dias C.N., Brasil Gadelha Farias L.A., Moreira Barreto Cavalcante F.J. Septic embolism in a patient with infective endocarditis and COVID-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(6):2160–2161. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Vivo S., Barberio M., Corrado C., et al. CRT implantation after TLE in a patient with COVID-19: endocarditis triggered by SARS-COV-2 infection? A case report. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/pace.14218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vélez-Páez J.L., Lopez-Rondon E., Jara-Gonzalez F.E., Castro-Reyes E. Native valve infective endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus hominis in a patient hospitalized with COVID-19. Report of a Case. Acta méd. peru. 2020;37(3):336–340. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders D.J., Sutter J.S., Tatooles A., Suboc T.M., Rao AK. Endocarditis complicated by severe aortic insufficiency in a patient with COVID-19: diagnostic and management implications. Case Rep Cardiol. 2020:2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/8844255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schizas N., Michailidis T., Samiotis I., et al. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of a critically Ill Patient with infective endocarditis due to a false-positive molecular diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21 doi: 10.12659/AJCR.925931. e925931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramos-Martínez A., Fernández-Cruz A., Domínguez F., et al. Hospital-acquired infective endocarditis during COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Prev Pract. 2020;2(3) doi: 10.1016/j.infpip.2020.100080. 100080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brotherton T., Miller CS. Infective endocarditis initially manifesting as pseudogout. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2021;34(4):496–497. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2021.1888632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castillo F.J., Anguita M., Castillo J.C., Ruiz M., Mesa D., Suárez de Lezo J. Changes in clinical profile, epidemiology and prognosis of left-sided native-valve infective endocarditis without predisposing heart conditions. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2015;68(5):445–448. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2014.12.014. (Engl Ed) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durante-Mangoni E., Bradley S., Selton-Suty C., et al. Current features of infective endocarditis in elderly patients: results of the international collaboration on endocarditis prospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2095–2103. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garg P., Ko D.T., Jenkyn K.M.B., Li L., Shariff SZ. Infective endocarditis hospitalizations and antibiotic prophylaxis rates before and after the 2007 American heart association guideline revision. Circulation. 2019;140(3):170–180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Sa D.D.C., Tleyjeh I.M., Anavekar N.S., et al. Epidemiological trends of infective endocarditis: a population-based study in Olmsted county. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(5):422–426. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0585. Minnesota. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gackowski A., Lipczyńska M., Lipiec P., Szymański P. Echocardiography during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: expert opinion of the working group on echocardiography of the polish cardiac society. Kardiol Pol. 2020;78(4):357–363. doi: 10.33963/KP.15265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skulstad H., Cosyns B., Popescu B.A., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritization, and protection for patients and healthcare personnel. Eur Heart J Cardiovas Imag. 2020;21(6):592–598. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liesenborghs L., Meyers S., Lox M., et al. Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: distinct mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to damaged and inflamed heart valves. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(39):3248–3259. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roshdy A., Zaher S., Fayed H., Coghlan JG. COVID-19 and the heart: a systematic review of cardiac autopsies. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.626975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goyal P., Choi J.J., Pinheiro L.C., et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York city. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kozak R., Prost K., Yip L., Williams V., Leis J.A., Mubareka S. Severity of coronavirus respiratory tract infections in adults admitted to acute care in Toronto, Ontario. J Clin Virol. 2020;126 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murdoch D.R., Corey G.R., Hoen B., et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the international collaboration on endocarditis-prospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):463–473. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Habib G., Lancellotti P., Antunes M.J., et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS), the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM) Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leone S., Ravasio V., Durante-Mangoni E., et al. Epidemiology, characteristics, and outcome of infective endocarditis in Italy: the Italian study on endocarditis. Infection. 2012;40(5):527–535. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0285-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.