Abstract

Background

Population-based analyses of patterns of care and survival of older patients diagnosed with grade II-III oligodendroglioma (OLI) or astrocytoma (AST) can aid clinicians in their understanding and care of these patients.

Methods

We identified patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2015 with primary glioma diagnoses (OLI or AST) who were older than 65 years using the latest release of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare–linked database. Medicare claims were used to identify cancer treatments (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy) from 2006 to 2016. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to describe overall survival (OS). Cox proportional hazards regression was used to associate variables of interest, including treatments in a time-dependent manner, with OS. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from multivariable, cause-specific competing risk models identified associations with treatments. All statistical tests were 2-sided.

Results

We identified 1291 patients comprising 158 with OLI, 1043 with AST, and 90 with mixed histologies. Median OS was 6.5 (95% CI = 6.1 to 7.3) months for the overall cohort, 22.6 (95% CI = 13.9 to 33.1) months for OLI, and 5.8 (95% CI = 5.3 to 6.4) months for AST. Patients who received surgery and patients who received both chemotherapy and radiation therapy in combination experienced better OS (HR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.79 to 0.96, and HR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.35 to 0.96, respectively). Over the time frame studied, there was a 4.0% increase per year in prescription of chemotherapy (P = .03) and a 2.0% improvement in OS for each calendar year (P = .003).

Conclusions

We provide population-based evidence that patients older than 65 years with grade II-III glioma have experienced increased chemotherapy use as well as improvement in survival over time.

Oligodendrogliomas (OLI) and astrocytomas (AST) are lower grade (II-III) primary brain neoplasms, which constitute approximately 35% of all gliomas in the United States with ASTs occurring 3 times more frequently than OLIs (1). These specific brain tumors are more common in younger patients with median ages at diagnosis of 43 and 48 years (2), respectively, with 70%-90% diagnosed in patients younger than 65 years (3,4). Because of a lack of prospective trials (5), there is controversy regarding the optimal management of older patients with OLI including the timing of radiotherapy and utility of chemotherapy; and there is no standardized treatment for older patients with AST, with many clinicians extrapolating from treatment of older patients with glioblastoma multiforme (6).

Population-based studies of glioma do not typically focus on older patients, though a few have. A study of patients 65 years and older with OLI from 1973 to 2012 reported decreasing all-cause mortality over time, highest mortality for patients 85 and older, and an associated univariable survival benefit with surgery (7). A study of patients older than 65 years with AST found that the oldest patients (75 years and older) were more likely to receive limited treatment and that survival varied by treatment combinations (8). The study on patients 65 years and older with OLI relied on Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) treatment variables, which have only moderate sensitivity to identify treatments received (9), and neither study incorporated the timing of treatments received, inevitably leading to biased conclusions (10,11).

More than a decade ago, we described the prognosis and patterns of care in older patients with OLI or AST using SEER-Medicare (12). Now, using a recent release of SEER-Medicare data, we aim to describe contemporary patterns of care and estimate overall survival in older patients with these gliomas. We identify factors associated with receipt of different treatment types and associate treatments with overall survival. Finally, we describe trends of care and survival over time to better aid clinicians in their understanding and care of patients older than 65 years with OLI and AST, a group of patients commonly excluded from randomized clinical trials (13).

Methods

Design

This was a population-based cohort study using SEER data linked with Medicare claims from 2006 through 2016. The SEER registries include more than 25% of all patients diagnosed with cancer in the United States. Medicare is the primary health insurer for Americans 65 years and older and covers medical care including, but not limited to, inpatient hospital treatment, outpatient care, and physician services. The SEER-Medicare–linked database is a unique resource offering a large population-based cohort, which can be used to longitudinally evaluate health outcomes (14). We used Medicare claims from the physician and supplier file, outpatient standard analytic file, provider analysis and review file, and the Part D event file. The Memorial Sloan Kettering institutional review board deemed this study exempt from review and waived the need for informed consent.

Cancer Cohort

We identified our cohort using the SEER-Medicare–linked databases from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2015. We selected patients diagnosed with a primary brain cancer from the SEER Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary file utilizing the siterwho1 variable (Brain: 31010). Furthermore, OLIs were identified with International Classification of Diseases 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) histologic type hist1 code of 9450 or 9451, and ASTs were identified with codes 9400-9420. Exclusions were made if any of the following occurred: patient lacked Part A or B Medicare coverage or belonged to a health maintenance organization in the year prior to OLI or AST diagnosis or through follow-up; OLI or AST diagnosis was made only at the time of death; month of OLI or AST diagnosis was missing; or OLI or AST diagnosis was made before age 66 years (could not calculate comorbidity status in the year prior to brain cancer diagnosis). The SEER program collects sociodemographic characteristics, including age at OLI or AST diagnosis, sex, race, year of OLI or AST diagnosis, marital status, cancer grade, geographic region, and census tract poverty level from registry records, and these variables were available in the SEER Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary file. Categories of race were determined by the SEER race recode variable and were as follows: Black, Other, Unknown, and White. The race category “other” included American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, and/or Pacific Islander. We used the World Health Organization grading based on ICD-O-3 histologic type codes to classify patients as grade II (histologic type codes 9450, 9400, 9410, 9411, 9420, and 9413), grade III (histologic type codes 9451 and 9401), or mixed grade (histologic type code 9382). Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation status was not available. For direct comparison with our previous publication (12), we also identified cancer grade with the SEER International Classification of Diseases 2nd edition (ICD-O-2) grade codes. Although explicit values of surgical margins cannot be determined from the SEER-Medicare data (15), there is some precedent in the literature using SEER surgery codes to define broad categories of surgical extent (4,16). To further detail those with Medicare claim codes for surgery in an exploratory analysis, we used the following surgery codes from the SEER registry: local excision and/or biopsy (code 20), subtotal resection (codes 21, 40), and gross total resection (codes 30, 55). Although there have been minor modifications to the codes in each edition of the SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual, the general definitions have remained relatively consistent (4,16).

Claims

We used Medicare claims from the physician and supplier file, outpatient standard analytic file, provider analysis and review file, and the Part D event file. Claims information was available through December 31, 2016, which was the end of follow-up. Claim codes (ICD-9) used for surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy have been previously described (12). Analogous ICD-10 codes were also used as applicable (Supplementary Table 1, available online). Charlson comorbidity score in the year prior to OLI or AST diagnosis was calculated (17).

In an exploratory analysis, for the subset of patients with complete Part D coverage from glioma diagnosis until death or last follow-up, we explored oral chemotherapeutic temozolomide (TMZ) and procarbazine, lomustine (cyclonexyl-chloroethyl-nitrosourea [CCNU]), vincristine (PCV), which is administered orally and intravenously. These codes are detailed in Supplementary Table 2 (available online).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical measures such as means, medians, ranges, and proportions were used to characterize the cohort under study overall and by glioma subtype. For the overall cohort and by glioma subtype, Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to present overall survival (OS) from date of primary glioma diagnosis until death for those who died prior to administrative follow-up (December 31, 2016) or until last administrative claim date (December 31, 2016) for those who were alive. OS comparison across glioma subtype was compared using the log-rank test.

Cox proportional hazards modeling was used to associate variables of interest with OS for the overall cohort and by glioma diagnosis. Wald χ2 tests were performed to generate P values for the association of variables of interest with OS. A time-dependent covariable was used for chemotherapy and radiation to incorporate the timing of the treatment as well as if the patient received the treatment. In addition to treatments, other variables included in the OS Cox models were age at first primary glioma diagnosis, sex, race, marital status, geographic registry region, census tract–based poverty, glioma subtype (for the overall cohort model only), tumor grade, Charlson comorbidity index in the year prior to glioma diagnosis, and year of glioma diagnosis. The appropriateness of the assumption of hazards proportionality was diagnosed with visual inspection of the log-minus-log plots and Schoenfeld residuals for each time-independent variable.

To investigate treatment patterns, cumulative incidence rates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated separately for each treatment (surgery, radiation therapy [RT], and chemotherapy) in the competing risks setting. Follow-up time was calculated from glioma diagnosis until treatment of interest, death (as a competing event), or last administrative follow-up (December 31, 2016), whichever occurred first. Comparison of cumulative incidence curves for each treatment type (separately) across glioma subtypes was performed with Gray’s test.

To associate variables of interest with receipt of treatment for the overall cohort and by glioma subtype, a cause-specific approach was used to account for the competing risk of death. Receipt of each individual treatment (surgery, RT, and chemotherapy) was modeled separately. Variables included in these models were age at first primary glioma diagnosis, sex, race, marital status, geographic registry region, census tract–based poverty, glioma subtype (for the overall cohort model only), tumor grade, Charlson comorbidity index in the year prior to glioma diagnosis, and year of glioma diagnosis. Wald χ2 tests were performed to generate P values for the association of variables of interest with receipt of individual treatments.

All tests were 2-sided with an alpha level of statistical significance set at 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

We identified 1291 patients diagnosed aged older than 65 years with primary OLI (n = 158, 12.2%), AST (n = 1043, 80.8%), or mixed histologies (n = 90, 7.0%) from 2006 to 2015. Of these, 40.4% were AST grade II, 40.4% were AST grade III, 6.4% were OLI grade II, 5.8% were OLI grade III, and 7.0% had mixed histology (Table 1). There were 688 male patients (53.3%) and 603 female patients (46.7%). There were 48 Black patients (3.7%), 58 patients with Other or Unknown race (4.5%), and 1185 White patients (91.8%).

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics

| Variable | Alla | Oligodendrogliomas | Astrocytomas |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Comorbidity index | |||

| 0 | 715 (55.4) | 93 (58.9) | 569 (54.6) |

| 1 | 277 (21.5) | 34 (21.5) | 229 (22) |

| ≥2 | 299 (23.2) | 31 (19.6) | 245 (23.5) |

| Chemotherapyb | |||

| No | 951 (73.7) | 108 (68.4) | 771 (73.9) |

| Yes | 340 (26.3) | 50 (31.6) | 272 (26.1) |

| RTb | |||

| No | 412 (31.9) | 48 (30.4) | 340 (32.6) |

| Yes | 879 (68.1) | 110 (69.6) | 703 (67.4) |

| Surgeryb | |||

| No | 769 (59.6) | 63 (39.9) | 670 (64.2) |

| Yes | 522 (40.4) | 95 (60.1) | 373 (35.8) |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| 66-69 | 299 (23.2) | 44 (27.8) | 234 (22.4) |

| 70-74 | 373 (28.9) | 41 (25.9) | 293 (28.1) |

| 75-79 | 300 (23.2) | 73 (46.2)c | 250 (24) |

| 80-84 | 219 (17) | 175 (16.8) | |

| ≥85 | 100 (7.7) | 91 (8.7) | |

| Geographic location | |||

| West or Midwest | 718 (55.6)c | 94 (59.5)c | 583 (55.9)c |

| South | 334 (25.9) | 35 (22.2) | 273 (26.2) |

| Northeast | 239 (18.5) | 29 (18.4) | 187 (17.9) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 752 (58.2) | 90 (57) | 609 (58.4) |

| Unmarried | 481 (37.3) | 68 (43)c | 389 (37.3) |

| Unknown | 58 (4.5) | 45 (4.3) | |

| Census tract poverty level | |||

| ≥10% | 579 (44.8) | 66 (41.8) | 474 (45.4) |

| <10% or unknown | 712 (55.2)c | 92 (58.2)c | 569 (54.6)c |

| Race | |||

| Black | 48 (3.7) | c | 42 (4) |

| Other/Unknownd | 58 (4.5)c | c | 47 (4.5)c |

| White | 1185 (91.8) | c | 954 (91.5) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 688 (53.3) | 84 (53.2) | 554 (53.1) |

| Female | 603 (46.7) | 74 (46.8) | 489 (46.9) |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| Continuous | 1291 (100) | 158 (100) | 1043 (100) |

| Subtype and WHO grade | |||

| OLI, II | 83 (6.4) | 83 (52.5) | e |

| OLI, III | 75 (5.8) | 75 (47.5) | e |

| Mixed | 90 (7) | e | e |

| AST, II | 521 (40.4) | e | 521 (50) |

| AST, III | 522 (40.4) | e | 522 (50) |

There are 90 patients with mixed histology who are included in the “All” column along with astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. AST = astrocytoma; OLI = oligodendroglioma; RT = radiation therapy; WHO = World Health Organization.

Ever received.

Agreement with SEER-Medicare does not allow the reporting of results fewer than 11 patients because of privacy. Some cells are omitted entirely or collapsed or combined to circumvent back calculation of reportable patients. The majority of patients with oligodendroglioma were White.

Other race includes American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, and/or Pacific Islander.

OLI grade II, OLI grade III, and mixed categories do not apply to the astrocytoma cohort. Similarly, AST grade II, AST grade III, and mixed categories do not apply to the oligodendroglioma cohort.

Treatment Patterns

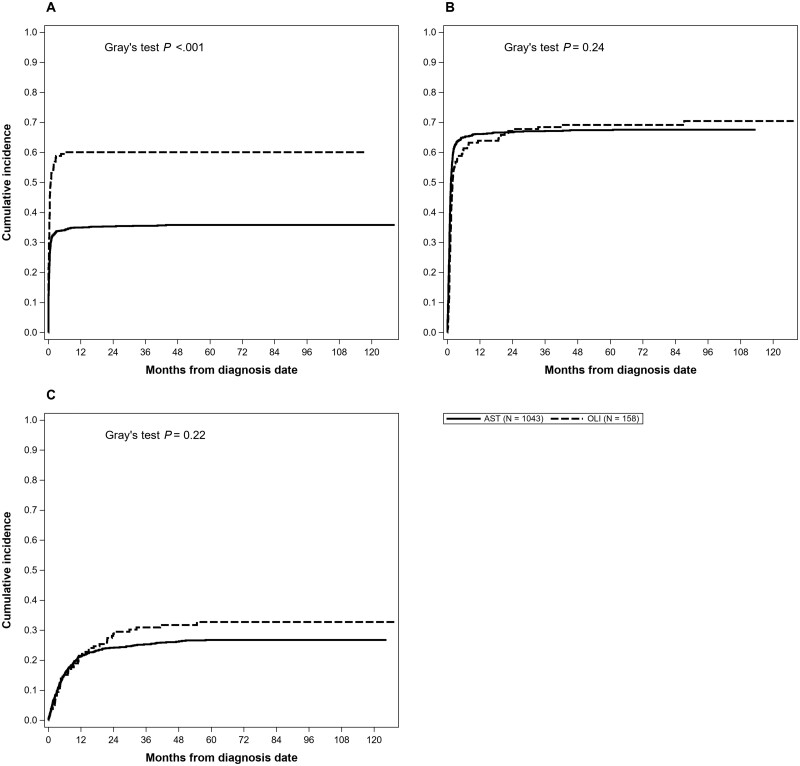

Using cumulative incidence to account for the competing risk of death, we estimated 2-year incidence of surgery was 40.1% (95% CI = 37.5% to 42.8%), which was statistically significantly different by subtype with 2-year incidence of surgery of 60.1% for OLI (95% CI = 52.4% to 67.8%) and 35.4% for AST (95% CI = 32.5% to 38.3%; P < .001) (Figure 1, A). In the multivariable model, OLI grade III had an increased association of receiving surgery compared with OLI grade II (HR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.27 to 2.91) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence curves of specific treatments for patients older than 65 years by glioma type. A) Shows the cumulative incidence of surgery in patients older than 65 years with oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma. Patients with oligodendroglioma were more likely to receive surgery compared with patients with astrocytoma. B) Shows the cumulative incidence of radiation therapy in patients older than 65 years with oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma. The cumulative incidence of radiation therapy did not differ by disease type. C) Shows the cumulative incidence of chemotherapy in patients older than 65 years with oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma. The cumulative incidence of chemotherapy did not differ by disease type. P values were calculated using a 2-sided Gray’s test. AST = astrocytoma; OLI = oligodendroglioma.

Table 2.

Predictors of treatments in the overall cohort

| Variable | Surgery |

Radiation |

Chemotherapy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI)a | P a | HR (95% CI)a | P a | HR (95% CI)a | P a | |

| Comorbidity index | ||||||

| 0 | Referent | .85 | Referent | .18 | Referent | .77 |

| 1 | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.33) | 1.17 (0.99 to 1.39) | 1.03 (0.78 to 1.35) | |||

| ≥2 | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.28) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.23) | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.23) | |||

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||||

| 66-69 | Referent | .27 | Referent | <.001 | Referent | .06 |

| 70-74 | 1.02 (0.81 to 1.29) | 1.10 (0.92 to 1.31) | 0.90 (0.69 to 1.17) | |||

| 75-79 | 1.07 (0.83 to 1.37) | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.09) | 0.85 (0.63 to 1.16) | |||

| 80-84 | 0.86 (0.65 to 1.15) | 0.72 (0.57 to 0.90) | 0.56 (0.37 to 0.84) | |||

| ≥85 | 0.71 (0.47 to 1.08) | 0.39 (0.27 to 0.57) | 0.60 (0.34 to 1.07) | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Referent | .87 | Referent | .20 | Referent | .11 |

| Unmarried | 1.02 (0.84 to 1.24) | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.05) | 0.76 (0.59 to 0.98) | |||

| Unknown | 1.11 (0.75 to 1.65) | 0.79 (0.56 to 1.11) | 0.95 (0.57 to 1.59) | |||

| Census tract poverty level | ||||||

| <10% | Referent | .40 | Referent | .43 | Referent | .24 |

| ≥10% | 0.97 (0.81 to 1.17) | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.11) | 0.83 (0.65 to 1.05) | |||

| Unknown | 0.45 (0.14 to 1.43) | 1.44 (0.75 to 2.74) | 1.25 (0.45 to 3.46) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 1.02 (0.65 to 1.62) | 0.83 (0.58 to 1.19) | 1.33 (0.78 to 2.26) | |||

| Otherb/Unknown | 0.84 (0.53 to 1.33) | .76 | 0.78 (0.55 to 1.11) | .24 | 0.77 (0.43 to 1.36) | .38 |

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Referent | .65 | Referent | .53 | Referent | .78 |

| Female | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.15) | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.10) | 0.97 (0.77 to 1.21) | |||

| Subtype and WHO grade | ||||||

| OLI, II | Referent | <.001 | Referent | <.001 | Referent | <.001 |

| AST, II | 0.76 (0.54 to 1.08) | 1.66 (1.22 to 2.25) | 1.33 (0.85 to 2.08) | |||

| OLI, III | 1.92 (1.27 to 2.91) | 1.91 (1.30 to 2.79) | 1.47 (0.84 to 2.59) | |||

| AST, III | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.02) | 2.24 (1.65 to 3.04) | 2.17 (1.40 to 3.37) | |||

| Mixed | 1.41 (0.93 to 2.14) | 1.62 (1.11 to 2.36) | 0.83 (0.44 to 1.53) | |||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| Continuous | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | .67 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | .38 | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.08) | .03 |

Adjusted for comorbidity index in the year prior to glioma diagnosis, age at glioma diagnosis, geographic location, marital status, census tract poverty level, race, sex, glioma subtype and WHO grade, and year of glioma diagnosis. Two-sided Wald χ2 tests were performed to generate P values for the association of variables with receipt of individual treatments. AST = astrocytoma; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; OLI = oligodendroglioma; WHO = World Health Organization.

Other race includes American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, and/or Pacific Islander.

We estimated 2-year incidence of RT was 67.2% (95% CI = 64.6% to 69.8%), which did not statistically significantly vary by glioma subtype (Figure 1, B). In the multivariable model, all other subtypes had an increased association of receiving RT when compared with OLI grade II, with AST grade III more than 2 times more likely than OLI grade II to receive RT (HR = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.65 to 3.04) (Table 2). We estimated the 2-year rate of chemotherapy was 24.4% (95% CI = 22.0% to 26.7%), and similar trends were seen in the multivariable model for glioma subtype and chemotherapy as were seen for RT (Figure 1, C).

Year of diagnosis was not associated with receipt of RT or surgery, but there was a 4.0% increased association for each calendar year with receipt of chemotherapy (HR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.08; P = .03). This was driven by the AST cohort (results not shown). Older ages were less likely to receive RT (ages 80-84 years: HR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.57 to 0.90; and ages 85 years and older: HR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.27 to 0.57), marginally less likely to receive chemotherapy (ages 80-84 years: HR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.37 to 0.84; and ages 85 years and older: HR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.34 to 1.07), but not less likely to receive surgery (ages 80-84 years: HR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.65 to 1.15; and ages 85 years and older: HR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.47 to 1.08) (Table 2).

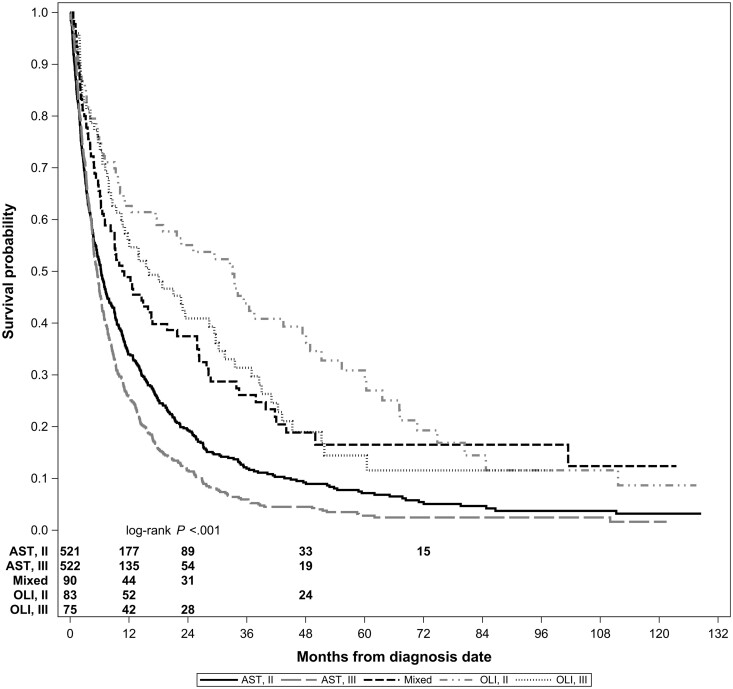

Overall Survival

Median overall survival was 6.5 (95% CI = 6.1 to 7.3) months for the overall cohort, 22.6 (95% CI = 13.9 to 33.1) months for 158 OLI patients, and 5.8 (95% CI = 5.3 to 6.4) months for 1043 AST patients (P < .001). Survival varied by subtype and grade as well (Figure 2). Using SEER grade for direct comparison with our previous publication (12), median OS for OLI grade II was 29.4 (95% CI = 1.3 to 67.1) months, 15.5 (95% CI = 10.2 to 28.3) months for OLI grade III, 10.4 (95% CI = 6.9 to 19.7) months for AST grade II, and 5.1 (95% CI = 4.7 to 5.8) months for AST grade III.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients older than 65 years by glioma type and World Health Organization grade. Numbers of patients at risk are provided by group. Some numbers are omitted entirely because of data use agreement with SEER-Medicare, which does not allow the reporting of results fewer than 11 patients, either directly or indirectly. Patients with oligodendroglioma grade II tumors experienced the best survival, and patients with astrocytoma grade III tumors experienced the worst survival. The P value was calculated using a 2-sided log-rank test. AST = astrocytoma; OLI = Oligodendroglioma; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

In the multivariable setting, older age, male sex, and higher comorbidity index was associated with worse OS (Table 3). Patients who received surgery and patients who received both chemotherapy and RT in combination experienced better OS (HR = 0.87, 95% CI= 0.79 to 0.96, and HR = 0.58, 95% CI= 0.35 to 0.96, respectively). In a separate multivariable model, we examined the effect of surgery type and found that patients with gross total resection experienced better OS (HR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.74 to 0.97) compared with patients with no surgery. This was driven largely by patients with AST (HR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.66 to 0.92), and although there was a similar pattern for patients with OLI, it was not statistically significant (HR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.67 to 1.42). Importantly, each year of diagnosis was associated with a 2.0% decrease in risk of death (HR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.96 to 0.99; P = .003), an association also seen separately for AST and OLI.

Table 3.

Predictors of survival in the overall cohort and by subtype

| Variable | All |

Oligodendrogliomas |

Astrocytomas |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI)a | P a | HR (95% CI)b | P b | HR (95% CI)b | P b | |

| Comorbidity index | ||||||

| 0 | Referent | <.001 | Referent | .02 | Referent | .008 |

| 1 | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.28) | 1.66 (1.14 to 2.43) | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.25) | |||

| ≥2 | 1.23 (1.09 to 1.37) | 1.40 (0.93 to 2.13) | 1.21 (1.07 to 1.37) | |||

| Chemotherapy and RTc | ||||||

| Chemo only | Referent | <.001 | Referent | <.001 | Referent | <.001 |

| Neither | 1.74 (1.06 to 2.87) | 1.25 (0.44 to 3.50) | 1.87 (1.05 to 3.33) | |||

| RT only | 0.87 (0.53 to 1.44) | 0.56 (0.20 to 1.58) | 0.93 (0.52 to 1.66) | |||

| Chemo + RT | 0.58 (0.35 to 0.96) | 0.38 (0.13 to 1.11) | 0.58 (0.32 to 1.04) | |||

| Surgery | ||||||

| No | Referent | .004 | Referent | .49 | Referent | .004 |

| Yes | 0.87 (0.79 to 0.96) | 0.89 (0.65 to 1.23) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.95) | |||

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||||

| 66-69 | Referent | .01 | Referent | <.001 | Referent | .17 |

| 70-74 | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.32) | 2.21 (1.46 to 3.35) | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.26) | |||

| 75-79 | 1.26 (1.10 to 1.44) | 1.96 (1.31 to 2.94) | 1.18 (1.02 to 1.36) | |||

| 80-84 | 1.21 (1.04 to 1.40) | 1.08 (0.66 to 1.76) | 1.18 (1.00 to 1.39) | |||

| ≥85 | 1.11 (0.90 to 1.35) | 2.04 (0.85 to 4.89) | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.29) | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Referent | .65 | Referent | .03 | Referent | .41 |

| Unmarried | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | 1.49 (1.06 to 2.11) | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.09) | |||

| Unknown | 0.92 (0.73 to 1.15) | 2.00 (1.01 to 3.95) | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.09) | |||

| Census tract poverty level | ||||||

| <10% | Referent | .13 | Referent | .22 | Referent | .01 |

| ≥10% | 1.10 (1.00 to 1.21) | 0.74 (0.53 to 1.04) | 1.16 (1.04 to 1.29) | |||

| Unknown | 1.26 (0.82 to 1.95) | 0.78 (0.25 to 2.44) | 1.52 (0.90 to 2.57) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.11) | 1.32 (0.52 to 3.40) | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.09) | |||

| Otherd/Unknown | 0.78 (0.62 to 0.98) | .06 | 0.43 (0.15 to 1.21) | .23 | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.15) | .32 |

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Referent | .02 | Referent | .007 | Referent | .10 |

| Female | 0.90 (0.81 to 0.99) | 0.63 (0.45 to 0.88) | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.02) | |||

| Subtype and WHO grade | ||||||

| OLI, II | Referent | <.001 | Referent | <.001 | e | e |

| OLI, III | 1.81 (1.38 to 2.39) | 2.21 (1.59 to 3.07) | e | e | ||

| Mixed | 1.53 (1.17 to 2.00) | e | e | e | e | |

| AST, II | 2.06 (1.67 to 2.54) | e | e | Referent | <.001 | |

| AST, III | 2.88 (2.33 to 3.56) | e | e | 1.41 (1.27 to 1.56) | ||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| Continuous | 0.98 (0.96 to 0.99) | .003 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | .02 | 0.98 (0.96 to 0.99) | .008 |

Adjusted for comorbidity index in the year prior to glioma diagnosis, treatment, age at glioma diagnosis, geographic location, marital status, census tract poverty level, race, sex, year of glioma diagnosis, and glioma subtype and WHO grade. Two-sided Wald χ2 tests were performed to generate P values for the association of variables with overall survival. AST = astrocytoma; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; OLI = oligodendroglioma; RT = radiation therapy; WHO = World Health Organization.

Adjusted for comorbidity index in the year prior to glioma diagnosis, treatment, age at glioma diagnosis, geographic location, marital status, census tract poverty level, race, sex, year of glioma diagnosis, and WHO grade. Two-sided Wald χ2 tests were performed to generate P values for the association of variables with overall survival.

Time-dependent variable.

Other race includes American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, and/or Pacific Islander.

OLI grade II, OLI grade III, and mixed categories do not apply to the astrocytoma cohort. Similarly, AST grade II, AST grade III, and mixed categories do not apply to the oligodendroglioma cohort.

Discussion

Using a recent release of population-based SEER-Medicare data, we identified a 2.0% improvement in survival each calendar year from 2006 to 2015. Median OS improved a range of 1 to 6 months for OLI grade III, AST grade II, and AST grade III from 1994-2002 (12) to 2006-2015. While not comprising results on only older patients, Dong et al. (4) also found that OS has improved for grade II and III astrocytoma patients from 1999 to 2010, and Brandel et al. (18) reported improved OS for grade III oligodendroglioma patients from 1999 to 2012. Although survival did not improve for OLI grade II, it is most likely an anomaly because of the exceedingly small number in this SEER-based histological group in the latest SEER-Medicare release. Furthermore, the 95% confidence interval in our current study included the median OS published previously for OLI grade II.

The cohort under study included patients diagnosed from 2006 to 2015. Previous reports from 2003 and 2007 demonstrated that older patients with malignant glioma benefited from surgery with regard to OS (19,20). The 2005 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines also recommended maximal safe resection where feasible for grades II and III gliomas (21). Thus, it follows that we identified no increase in surgery over time and that surgery was associated with more favorable OS. Interestingly, we found a decreased risk of death associated with surgery across subtypes, though this was not statistically significantly reduced for patients with OLI. Furst et al. (7) reported similar findings in a SEER study of older patients with OLI, though the time frame studied was from 1973 to 2012 and other treatments were not modeled as covariates.

At the outset of the time frame currently under study, RT had been shown to improve progression-free survival but not OS for patients with low-grade gliomas (22,23). However, by the end of our study period in 2015, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommended maximal safe resection where feasible for low-grade gliomas followed by RT and PCV or RT and TMZ for those older than 40 years (21). For patients with grade III OLI, at the beginning of our study period, 2 clinical trials had reported PCV and RT was no better than RT alone with regard to OS (24,25). By the end of our study period herein, however, the trial data matured to reveal that PCV and RT doubled survival compared with RT alone (26-28). While these results accumulated, TMZ became widely available and the chemotherapeutic of choice for anaplastic oligodendrogliomas (29). Grade III AST, which is typically treated using glioblastoma multiforme guidelines (30,31), would have been influenced by the Stupp protocol published in 2005 recommending RT and TMZ (32). Considering these published results and changing guidelines over our study period, it is not surprising that we identified no increase in radiation over time but reported a 4% increase in chemotherapy with each calendar year from 2006 to 2015.

We recently published a SEER-Medicare report on patients older than 65 years with glioblastoma (33). Although the overall focus differed based on glioma histology, we did find interesting similarities between our study on glioblastoma and the current study of lower-grade gliomas. Older patients with glioblastoma were less likely to receive standard of care treatment than their younger counterparts. Furthermore, older patients who received standard of care treatment had improved survival. A standard of care treatment regimen does not exist in the same manner for patients with OLI and AST as it does for those with glioblastoma. Nevertheless, we note that prior publications report 60%-70% of all lower-grade glioma patients receiving surgery (34,35), whereas in the current report, only 40% of patients older than 65 years with lower-grade glioma received surgery. We also observed an improved survival associated with surgery in our current older population.

In 2016, the World Health Organization classification for grade II and III gliomas was modified to include IDH mutation status. This revision from a histologically based categorization to a molecularly based categorization reclassified a substantial proportion of gliomas (36,37). Following this reclassification, it has become well established that IDH mutant gliomas are more sensitive to RT and chemotherapy, which may explain why IDH mutations predict favorable outcomes in gliomas (38). IDH mutation status was not available in the current SEER-Medicare data release analyzed herein, but we suspect to see similar trends in future reports.

We report an improved survival over our study period with a corresponding increase in prescription of chemotherapy. Barnholtz-Sloan et al. (8) reported on patients older than 65 years with AST in SEER-Medicare and demonstrated reduced mortality in patients with surgery, RT, and chemotherapy, though these results were from an earlier time frame (1991-1999) and treatment timing was not incorporated. We cannot be certain that our reported change in chemotherapy prescription patterns caused the improvement in survival, however, we do posit that this is plausible, particularly considering that combination chemotherapy and RT resulted in a 42.0% reduced risk of death in our cohort.

Our study has some limitations. First, the linked SEER-Medicare databases do not provide information on performance status or molecular markers, which can guide treatment decisions and affect prognosis. Second, the administrative nature of these datasets prevents us from providing information on treatment preferences of individual patients and attitudes of providers toward recommendations. Third, we were not able to investigate specific chemotherapies commonly used such as TMZ or PCV because of a limited number of patients reported as having Medicare claims for these specific regimens. Fourth, these results are, by design, applicable only to patients aged 66 years and older. It is unclear if age may modify the effect of treatment on survival, and we are unaware of any publications exploring the interaction in glioma allcomers. However, our results come from national population-based data that covers approximately 35% of the US population. In addition, 93% of SEER patients older than age 65 years have linked Medicare claims data, suggesting our findings are robust and widely applicable to the population we studied (14,39).

Utilizing the linked SEER-Medicare database, we characterized treatment patterns and prognosis of patients older than 65 years with oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma using a population-based study design. We found that treatment patterns changed over the period with more chemotherapy being prescribed, and we found survival patterns changed over the period with decreased risk of death.

Funding

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (P30 CA008748).

Notes

Role of the funder: The funder had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: Dr Diamond discloses unpaid editorial support from Pfizer Inc and serves on an advisory board for Day One Therapeutics and Springworks Therapeutics, both outside the submitted work. All other authors have no disclosures.

Author contributions: ASR: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; SML: formal analysis, visualization, writing—review and editing; SG: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; ELD: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing; KSP: conceptualization, supervision, methodology, writing—review and editing.

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute (NCI); the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); Information Management Services (IMS), Inc; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries included in the SEER-Medicare database.

Supplementary Material

Data Availability

The data underlying this article were provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) by permission. Data will be shared on request to the corresponding author with permission of the NCI, SEER registries, and CMS.

References

- 1. Davis ME. Epidemiology and overview of gliomas. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34(5):420–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ostrom QT, Cote DJ, Ascha M, Kruchko C, Barhnholtz-Sloan JS.. Adult glioma incidence and survival by race or ethnicity in the United States from 2000 to 2014. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(9):1254–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller KD, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, et al. Brain and other central nervous system tumor statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(5):381–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dong X, Noorbakhsh A, Hirshman BR, et al. Survival trends of grade I, II, and III astrocytoma patients and associated clinical practice patterns between 1999 and 2010: a SEER-based analysis. Neurooncol Pract. 2016;3(1):29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Albai KS.. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer to treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(27):2061–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gállego Pérez-Larraya J, Delattre J-Y.. Management of elderly patients with gliomas. Oncologist. 2014;19(12):1258–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furst T, Hoffman H, Chin LS.. All-cause and tumor specific mortality trends in geriatric oligodendroglioma (OG) patients: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;73:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Williams VL, Maldonado JL, et al. Patterns of care and outcomes among elderly individuals with primary malignant astrocytoma. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(4):642–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Noone AM, Lund JL, Mariotto A, et al. Comparison of SEER treatment data with Medicare claims. Med Care. 2016;54(9):e55–e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beyersmann J, Gastmeier P, Wolkewitz M, Schumacher M.. An easy mathematical proof showed that time-dependent bias inevitably leads to biased effect estimation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(12):1216–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beyersmann J, Wolkewitz M, Schumacher M.. The impact of time-dependent bias in proportional hazards modelling. Stat Med. 2008;27(30):6439–6454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iwamoto FM, Reiner AS, Nayak L, Panageas KS, Elkin EB, Abrey LE.. Prognosis and patterns of care in elderly patients with glioma. Cancer. 2009;115(23):5534–5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bertagnolli MM, Singh H.. Treatment of older adults with cancer—addressing gaps in evidence. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(12):1062–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF.. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(suppl 8):IV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Measures that are limited or not available in the data; 2021. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seermedicare/considerations/measures.html#17. Accessed November 6, 2021.

- 16. Lanman TA, Compton JN, Carroll KT, et al. Survival patterns of oligoastrocytoma patients: a Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) based analysis. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2018;11:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR.. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brandel MG, Alattar AA, Hirshman BR, et al. Survival trends of oligodendroglial tumor patients and associated clinical practice patterns: a SEER-based analysis. J Neurooncol. 2017;133(1):173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vuorinen V, Hinkka S, Farkkila M, Jaaskelainen J.. Debulking or biopsy of malignant glioma in elderly people—a randomised study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145(1):5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martinez R, Janka M, Soldner F, Behr R.. Gross-total resection of malignant gliomas in elderly patients: implications in survival. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2007;68(4):176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brem SS, Bierman PJ, Black P, et al. ; for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Central nervous system cancers: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2005;3(5):644–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karim ABMF, Afra D, Cornu P, et al. Randomized trial on the efficacy of radiotherapy for cerebral low-grade glioma in the adult: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study 22845 with the Medical Research Council study BRO4: an interim analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52(2):316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van den Bent MJ, Afra D, de Witte O, et al. ; for the EORTC Radiotherapy and Brian Tumor Groups and the UK Medical Research Council. Long-term efficacy of early versus delayed radiotherapy for low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in adults: the EORTC 22845 randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9490):985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cairncross G, Berkey B, Shaw E, et al. Phase III trial of chemotherapy plus radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone for pure and mixed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: Intergroup Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial 9402. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2707–2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van den Bent MJ, Carpentier AF, Brandes AA, et al. Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine improves progression-free survival but not overall survival in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendrogliomas: a randomized European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2715–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cairncross G, Wang M, Shaw E, et al. Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term results of RTOG 9402. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Van den Bent MJ, Brandes AA, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term follow-up of EORTC brain tumor group study 26951. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cairncross JG, Wang M, Jenkins RB, et al. Benefit from procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine in oligodendroglial tumors is associated with mutation of IDH. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abrey LE, Louis DN, Paleologos N, et al. ; for the Oligodendroglioma Study Group. Survey of treatment recommendations for anaplastic oligodendroglioma. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9(3):314–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Omuro A, DeAngelis LM.. Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310(17):1842–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Price RL, Chiocca EA.. Evolution of malignant glioma treatment: from chemotherapy to vaccines to viruses. Neurosurgery. 2014;61(CN_suppl_1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stupp R, Mason WP, Van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldman DA, Reiner AS, Diamond EL, DeAngelis LM, Tabar V, Panageas KS.. Lack of survival advantage among re-resected elderly glioblastoma patients: a SEER-Medicare study. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;3(1):vdaa159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu S, Liu X, Zhuang W.. Prognostic factors associated with survival in patients with diffuse astrocytoma. Front Surg. 2021;8:712350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alattar AA, Brandel MG, Hirshman BR, et al. Oligodendroglioma resection: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) analysis. J Neurosurg. 2018;128(4):1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nabors LB, Portnow J, Ahluwalia M, et al. Central Nervous System Cancers, version 3.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(11):1537–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Han S, Liu Y, Cai SJ, et al. IDH mutation in glioma: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Br J Cancer. 2020;122(11):1580–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. http://www.seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html. Accessed February 26, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article were provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) by permission. Data will be shared on request to the corresponding author with permission of the NCI, SEER registries, and CMS.