Abstract

Sporotrichosis is a cosmopolitan subcutaneous mycosis caused by Sporothrix species. Recently, this mycosis has gained notoriety due to the appearance of new endemic areas, recognition of new pathogenic species, changes in epidemiology, occurrence of outbreaks, and increasing numbers of cases. The purpose of this study is to analyze the peculiarities of sporotrichosis cases in Brazil since its first report in the country until 2020. In this work, ecological, epidemiological, clinical, and laboratorial characteristics were compiled. A systematic review of human sporotrichosis diagnosed in Brazil and published up to December 2020 was performed on PubMed/MEDLINE, SciELO, Web of Science, and LILACS databases. Furthermore, animal sporotrichosis and environmental isolation of Sporothrix spp. in Brazil were also evaluated. The study included 230 papers, resulting in 10,400 human patients. Their ages ranged from 5 months to 92 years old and 55.98% were female. The lymphocutaneous form was predominant (56.14%), but systemic involvement was also notably reported (14.34%), especially in the lungs. Besides, hypersensitivity manifestations (4.55%) were described. Most patients had the diagnosis confirmed by isolation of Sporothrix spp., mainly from skin samples. Sporothrix brasiliensis was the major agent identified. HIV infection, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes were the most common comorbidities. Cure rate was 85.83%. Concerning animal sporotrichosis, 8538 cases were reported, mostly in cats (90.77%). Moreover, 13 Sporothrix spp. environmental strains were reported. This review highlights the burden of the emergent zoonotic sporotrichosis in Brazil, reinforcing the importance of “One Health” based actions to help controlling this disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-021-00658-1.

Keywords: Sporotrichosis, Sporothrix, Brazil, Diagnosis, Clinical manifestation

Introduction

Sporotrichosis is a fungal disease mostly found in tropical and subtropical areas. It is considered the most frequent subcutaneous mycosis in Latin America, where it is endemic [1]. Thermo-dimorphic fungi of the genus Sporothrix cause this mycosis. They have a broad genomic diversity, which lead to the description of at least seven species reported as agents of human infection. Sporothrix schenckii, Sporothrix brasiliensis, Sporothrix globosa, and Sporothrix luriei are the most clinically relevant species, while Sporothrix mexicana, Sporothrix pallida, and Sporothrix chilensis are more commonly found in the environment, rarely causing disease [2–5].

The etiological agents of sporotrichosis grow in soil and decaying vegetation such as dead wood, sphagnum moss, and hay. Humans usually acquire the infection during outdoor activities such as farming, gardening, and similar occupations, through a traumatic inoculation by materials containing these fungi [6, 7]. Infection also occurs through zoonotic transmission usually associated with scratches or bites of infected animals, especially cats [4, 8–10]. Less frequently, the inhalation of Sporothrix spp. infectious particles present in the environment may occur, leading to the clinical presentation known as primary pulmonary sporotrichosis [11, 12].

Even though sporotrichosis has been described worldwide, there are curious divergences regarding the geographic distribution and the incidence of the etiological agents. Sporothrix schenckii, the first pathogenic species described, is particularly found in South Africa, Australia, North and Central America, and Western South America. On the other hand, S. globosa occurs primarily in Asia, mainly in China. In Europe, where a few number of sporotrichosis cases are currently reported, there are a diversity of species reported, including S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. mexicana [1, 13]. To date, S. brasiliensis occurs exclusively in South America, especially in Brazil, and it is mostly associated with zoonotic disease, unusual clinical manifestations of human disease, usually exhibiting high virulence [4, 14–17]. In Brazil, the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro State is the most important endemic area, with a large number of human and animal cases in the last 20 years [4, 9].

Several clinical forms of sporotrichosis have been described, but the skin is the major organ affected, with lymphocutaneous and fixed cutaneous forms observed in the majority of the cases [18–20]. However, increasing atypical clinical manifestations has also been described, such as systemic forms, involving the bone and joints, the lungs, and the central nervous system (CNS), as well as mucosal and immunoreactive presentations [20–22].

The gold standard for the sporotrichosis diagnosis is the isolation and identification of Sporothrix spp. from clinical specimens. Compared with culture, the direct microscopy presents low sensitivity and specificity. Yeast-like cells are usually observed in direct examination of samples collected from immunosuppressed human patients and cats. The sensitivity of histopathology in humans is also low due to scarce fungal cells in parasitism, but the presence of asteroid bodies, although rare in Brazilian sporotrichosis cases, may point to the diagnosis of this mycoses [23]. Serological tests exhibit high sensitivity and specificity and may represent an important diagnostic tool not only for sporotrichosis diagnosis, but also for clinical follow-up [20, 24, 25]. Molecular assays based on DNA amplification can easily detect Sporothrix spp. from fungal isolates or directly from clinical samples with low fungal burden, without the necessity of sequencing. These assays may enhance the time for identification when compared with phenotypic tests; however, they are limited to research centers [18–20].

Currently, itraconazole is the drug of choice for sporotrichosis treatment. Potassium iodide, terbinafine, and amphotericin B are also drugs currently used in many cases [20, 26]. Posaconazole is an effective and well-tolerated drug, indicated for refractory cases. However, considering the low availability due to its high cost, few sporotrichosis cases have been treated with this antifungal drug [27, 28]. The treatment depends essentially on the clinical form and the immunological status of the host. Both local heat and cryosurgery are therapeutic strategies when conventional drugs are contraindicated or as adjuvant treatment [20, 29–31].

Sporotrichosis has become a great public health problem due to the progressive increase in the number of cases in last years. In Brazil, for instance, the disease exhibits a worrisome geographical expansion to many states, and it is even advancing abroad, crossing other countries frontiers [4, 32–34]. So far, sporotrichosis is not a national notifiable disease in all Brazilian territory, and therefore, it is not possible to know the real burden of the disease in this country. A review of cases reported in the literature can help to understand the progression and distribution of sporotrichosis across the country. The authors performed a systematic review of Brazilian cases of human sporotrichosis, from its first report until December 2020. Additionally, a review of the literature about zoonotic and environmental cases was carried out, aiming to answer the questions of how sporotrichosis is spreading throughout Brazil, where are the major endemic areas, and which is the profile of patients presenting this mycosis in the country. Moreover, based on the One Health concept, we also investigated how animals and the environment are involved with sporotrichosis in Brazil.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

An extensive review was conducted in four different databases: Pubmed/MEDLINE, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Web of Science, and Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS). The bibliographic survey was conducted up to January 4th, 2021, including papers published from 1907 up to December 2020. The search strategy included a combination of keywords: Sporothrix [AND] Brazil or Sporotrichosis [AND] Brazil, in order to find published sporotrichosis case reports in Brazil. All studies that provided information supporting features of sporotrichosis’ clinical manifestations with or without the isolation of Sporothrix spp., such as sporotrichosis diagnosed only through serologic test or by positive intradermal tests with sporotrichin when clinical and epidemiologic data to support the sporotrichosis diagnosis were included.

Publications describing non-sporotrichosis studies, non-Brazilian cases, studies written and published in a language other than English, Spanish, or Portuguese, review papers, duplicate results, and studies with insufficient information, such as the lack of data about the clinical manifestations and/or method of diagnosis that would define a sporotrichosis case were excluded from this systematic review. Besides, studies not identified with our search strategy, but fulfilling the inclusion criteria (sporotrichosis case diagnosed in Brazil), were carefully recovered from the reference lists of each paper initially included in this study, as well as from the reference lists of excluded review papers (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart demonstrating the methodology used in this systematic review and the number of Brazilian sporotrichosis papers included in this study published from 1907 up to December 2020

A small analysis was performed on papers describing animal sporotrichosis cases in Brazil and isolation of Sporothrix spp. from the environment of this country. For these papers, information about the geographic distribution of the cases, the source of fungal isolation, and clinical data (when available) were retrieved.

Data analysis and variables of interest

The study was conducted according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [35] and was registered on PROSPERO, under the number 248098. The papers were selected based on the title and the abstract by three independent reviewers. Their full texts were analyzed if they fulfilled both inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the disagreements were solved by two examiners consensus.

During the analysis, efforts were made to collect as much as possible information about sporotrichosis cases in Brazil. The following data was collected: language and year of publication, sociodemographic, epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory data. Regarding sociodemographic and epidemiologic data, age, gender, occupation, Brazilian State where the case was diagnosed, and possible forms of infection were included. Clinical form, location of the lesion, comorbidities, type of treatment, and outcome were the clinical data evaluated. The definition of clinical forms was based on the most recent classification proposed by Orofino-Costa et al. [20]. Among the laboratory data, the diagnostic method and clinical specimens from which fungal isolation were performed, and molecular identification of Sporothrix species, when available, was included.

Recommendations for practice analysis

The discussion and conclusion sections of the included human sporotrichosis papers were reviewed in order to identify the main recommendations related to practice of the authors with emphasis on the clinical therapeutic management and epidemiological control of sporotrichosis.

Data analysis

The determination of the frequency of variables herein studied, such as language, year of publication, sociodemographic, epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory data, as well as graphics, was performed with the Microsoft Excel (2016) software.

Cartographic analyses

The thematic map of the sporotrichosis distribution in Brazil was created using the Qgis 3.14.15 software. Cartographic bases of map were obtained from Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics IBGE, 2017.

Results

Studies selection

The initial research identified 1777 studies. All duplicate papers from the three databases were excluded. After the assessment of titles and abstracts from the 790 remaining papers, 588 studies were excluded, as they did not meet at least one of the exclusion criteria. Finally, 202 papers were selected, but ten studies needed to be further excluded because they were not available online or in Brazilian public libraries. Thirty-eight additional papers were recovered from the reference lists of eligible papers and from the review papers excluded from this analysis, totalizing 230 studies included in this systematic review (Online Resource 1). The 230 papers evaluated were published between 1907 and 2020. Regarding the language, 78.70% were published in English, 20.43% in Portuguese, and 0.87% in Spanish.

Human sporotrichosis in Brazil

From 1907 to 2020, 10,400 human sporotrichosis cases were reported in the literature. Figure 2 shows the number of cases over the years according to the number of publications.

Fig. 2.

Sporotrichosis: number of publications (orange bars) and number of cases (blue line) in Brazil, 1907–2020

Demographic data

Among the 10,400 sporotrichosis cases, 8974 patients had available gender information. From these, 55.98% were female and 44.02% were male. Patients’ age ranged from 5 months to 92 years, with a greater incidence in persons between the thirtieth and fourth decades of life.

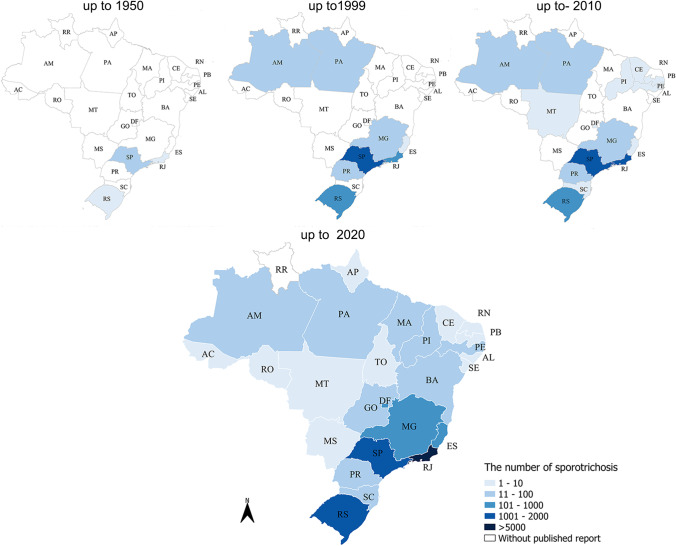

Sporotrichosis occurred endemically with a high number of cases especially in the South and Southeast regions of the country. Human sporotrichosis cases were reported in all Brazilian states and the Federal District, except in Roraima (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Geographic distribution of the number of sporotrichosis cases diagnosed in Brazil (1907–2020)

Transmission forms

Most patients 5996 (57.65%) did not have information about the transmission form of the disease. Zoonotic transmission occurred in 3516 (79.84%) patients, mostly through bites and or scratches by infected animals or just contact with them. Feline zoonotic transmission form was almost exclusive 3492 (79.3%). Other animals involved in sporotrichosis transmission (0.54%) were armadillos (n = 10), rats (n = 4), dogs (n = 3), fishes (n = 2), insects (n = 2), cockatiel, mosquito, and guinea pig one case each. The sapronotic transmission was formally reported in 884 (20.07%) sporotrichosis cases. Other transmission forms reported (0.09%) were own nail inoculation in two cases [36, 37], trauma during a soccer game in one case [38], and another case developed after an injury with bone meat [39].

Occupational activities

Risk factors related to professional or leisure activities were present in 1522 patients (14.63%): 784 patients (51.51%) were farmers, and 11 (0.72%) worked with gardening or floriculture. Two patients (0.13%) were fisherman, 68 cases of sporotrichosis (4.47%) occurred in veterinarians or in pet shop workers, and three patients (0.20%) were laboratory workers. Other occupations reported that may be associated with injuries by contaminated materials include bricklayers, joiners, carpenters, and builders including 23 patients (1.51%), 61 mine workers (4.01%), and 570 patients (37.45%) only developed domestic activities.

Diagnosis

From the 10,400 patients reported in the Brazilian literature, 2664 (25.62%) were excluded from this particular analysis due to the lack of information about diagnosis within the full texts. Sporothrix spp. was isolated from clinical samples of 5051 patients (65.29%). Among them, 193 cases (2.49%) were also diagnosed by direct microscopy besides the culture. Histological examination and molecular test were diagnostic positive in 128 (1.65%) and five sporotrichosis cases (0.06%), respectively. Immunological tests for antibody detection in serum samples were the main presumptive indicators of sporotrichosis diagnosis, used at least in 824 patients (10.65%) with the disease, alone or with other diagnostic tests. Furthermore, in this systematic review, we considered positive intradermal tests with sporotrichin as a diagnostic test for sporotrichosis infection corresponding 173 patients (2.24%), so they were included in the diagnostic chart. Detailed information about sporotrichosis diagnosis in Brazil is presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Diagnostic methods employed in the sporotrichosis diagnosis in Brazil during the period of 1907 to 2020

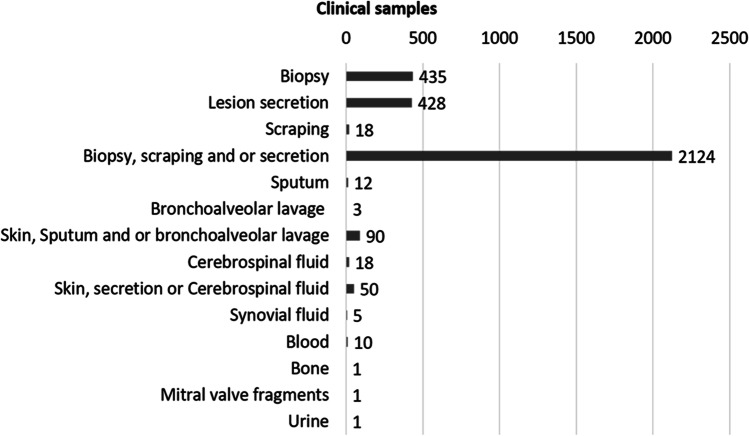

Among the clinical samples that were reported by the studies, isolation of the sporotrichosis agent was most often successful in exudates, biopsies, and/or scraping from cutaneous lesions 94% (n = 3005). Apart from skin samples, isolation of Sporothrix spp. was also reported from cerebrospinal fluid 0.56% (n = 18), respiratory samples 0.5% (n = 15), or blood cultures 0.31% (n = 10). Further data about clinical samples are shown in Fig. 5. In addition, 187 human patients (1.8%) had Sporothrix DNA identified, and most of them (75.40%) were S. brasiliensis, followed by S. schenckii (20.32%), S. globosa, and S. chilensis (2.14%) each.

Fig. 5.

Isolation of Sporothrix spp. from clinical sample

Clinical presentation

Regarding the clinical forms of sporotrichosis, the lymphocutaneous form was predominant, occurring in 3069 patients (56.14%), followed by fixed cutaneous, with 1482 cases (27.11%). The mucosal form was observed in 87 patients (1.59%), and among them, 34 had skin lesions. Multiple inoculations were reported in 11 cases (0.20%), and immunoreactive forms were reported in 249 patients (4.55%), with or without primary infectious skin lesions. The main hypersensitivity form reported was reactive arthritis, which occurred in 100 patients (40.2%), followed by erythema nodosum in 84 reported cases (33.7%). Other immunoreactivity presentations observed were erythema multiform and Sweet syndrome, reported in 52 (20.9%) and 13 patients (5.2%), respectively. Systemic involvement was reported in 784 sporotrichosis cases (14.34%), and in this context, the main presentations were the cutaneous disseminated and pulmonary forms, with 249 (31.76%) and 233 patients (29.72%), respectively. The osteoarticular system involvement was reported in 30 cases (3.83%), neurological in 27 patients (3.44%), and 1 patient (0.13%) presented endocarditis due to S. brasiliensis. Furthermore, five patients (0.64%) presenting systemic forms with more than one organ affected were reported as follows: lung and central nervous system (n = 1); lung and bone (n = 2); bone and central nervous system (n = 1); and lung, bone, and central nervous system (n = 1). Other 239 systemic cases (30.48%) were not classifiable by data present within the reports and 4933 cases (47.43%) did not have enough information about clinical forms.

Concerning the body sites affected, the main location reported, when this information was available, was the upper limbs, 2208 patients (62.66%), and the most important organ affected, apart from the skin, were the lungs, 237 sporotrichosis cases (6.73%). In 6,876 cases (66.12%), the studies did not provide enough information about the lesion site. More details about involved sites are described in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Sites of the body and organs involved in the sporotrichosis cases

Risk factors

Most of the reported cases 9512 (91.46%) did not describe comorbidities for the patients. Among comorbidities or conditions reported (n = 922) that could worsen the sporotrichosis evolution or represent difficulty to the treatment, high blood pressure and/or cardiovascular disease were the main diseases reported with 312 cases (33.8%), while 156 patients (16.9%) had HIV-coinfection. Thirty one (3.4%) had other immunosuppressive conditions such as solid-organ transplantations receiving immunosuppressive therapies, liver (n = 4), kidney (n = 8), neoplasia (n = 6), long-term corticosteroid therapy (n = 8), chronic degenerative diseases (n = 4), and agranulocytosis (n = 1). In addition, diabetes, alcoholism, and smoking were described in 124 (13.4%), 56 (6.1%), and 21 patients (2.3%), respectively. Other six patients (0.7%) were reported to use illicit drugs. Pregnancy was reported in 30 women (3.3%) with sporotrichosis. Other risk factors, such as metabolic, chronic, and infectious diseases, 187 cases (20.1%) were reported, and among them, one case of therapeutic failure was described due to bariatric surgery.

Treatment

Monotherapy was employed in 2486 patients (83.65%). Among them, itraconazole was the major drug prescribed, in 63% cases, followed by potassium iodide in 30%, terbinafine in 4.5%, and alternative treatments, such as local heat and cryosurgery, in 0.9%. Other monotherapies represented 1.6% including amphotericin B, posaconazole, fluconazole, and ketoconazole. In addition, ancient studies with N-methyl-glucamine antimoniate (gluncanthin), intradermal sporotrichin injections, iodine, and sodium iodide were identified. Therapeutic associations were reported in 486 patients (16.35%). Antifungal drugs combined with local heat, cryosurgery, or surgery corresponded to 47.3% of the therapeutic combinations. Itraconazole and potassium iodide with any other antifungal drug were used in 12% and 4.5% of the cases, respectively. Other associations were described for instance amphotericin B with other antifungal excepted itraconazole (n = 3). Information about the therapy was not available in 7376 (70.92%) patients.

Outcome

Outcome was available for 3078 cases, and the cure rate was 85.83%, whereas the mortality was 3.41% and 7.54% abandoned the treatment. Spontaneous regression was described in 52 patients (1.69%), and refractoriness to treatment occurred in 16 cases (0.52%). Sequela was reported in 20 patients (0.65%), usually secondary to ocular sporotrichosis, such as fibrosis (n = 5), dacryocystitis (n = 3), or blindness (n = 2). Other three patients had bone complications, as permanent deformities, one of them remains wheelchair-bound. In ten studies, 11 patients (0.36%) were still under treatment.

Animal sporotrichosis in Brazil

We detected 8538 animal cases reported in the literature. Among them, 7750 (90.77%) were cats and 676 (7.92%) dogs. Other animals included equines (n = 2), bovines (n = 40), rats (n = 40), and wild animals (24 coati, 3 felines; 2 primates – (Cebus apella); and 1 giant anteater). Two studies also reported isolation of Sporothrix spp. from the oral cavity (n = 1) and nail fragments (n = 7) of healthy cats.

Cases of spororotrichosis in domestic animals reported in the literature (n = 8,413) occurred in 12 Brazilian states, and 13 animals did not report the geographic origin. Most cases were feline sporotrichosis and reported in Rio de Janeiro and Rio Grande do Sul (6060 (72%) and 1137 (13.51%) cases, respectively). Detailed distribution of domestic animals across the Brazilian states is presented in Fig. 7 Data of 1324 feline cases were available and included in this evaluation. The rate of cure was 56.72%, whereas the mortality rate was 24.32%. Abandon of the treatment occurred in 13.07%, and treatment failure was reported in 5.89%. Moreover, neutering data was available for 1235 felines, and 67.13% were not sterilized. Furthermore, 521 isolates from cats (6.72%) were molecularly identified: 99.62% corresponded to S. brasiliensis and 0.38% to S. schenckii.

Fig. 7.

Geographic distribution of domestic animals with sporotrichosis reported in Brazil until 2020

Environmental Sporothrix isolation

Six studies reported the isolation of 13 Sporothrix spp. strains from the environment. Regarding the environmental samples, some were related to soil (n = 2), wood (n = 2), straw (n = 1), and armadillo burrow (n = 1), all of them from São Paulo State. Whereas four were isolated from a house where an infected cat lived and two from a veterinary clinic furniture, moreover, one sample was isolated from feces at sand heap from the backyard of another residence where cats with sporotrichosis lived.

Recommendations for practice

A summary of the advices retrieved from the studies evaluated including human and animal management in terms of diagnosis, therapeutics, and epidemiological control of sporotrichosis are presented in the online resource 1. In brief, we found recommendations for practice in 53 studies. Seven studies had recommendations directed for pet owners, seven for government workers, three for veterinary doctors, and two for laboratory personnel. Most of recommendations were directed for clinicians, and they were related to treatment (n = 5), sporotrichosis management during pregnancy (n = 2), sporotrichosis management in people living with HIV/AIDS (n = 3), diagnosis (n = 24), and differential diagnosis (n = 4).

Discussion

Sporotrichosis is a cosmopolitan mycosis mostly reported in Latin America [1]. In Brazil, it is the main subcutaneous mycosis, widely dispersed over the country, with high number of the cases in South and Southeast, especially in Rio de Janeiro State (Fig. 3). Due to the high number of cases, most of them related to the zoonotic transmission by cats, sporotrichosis has become a compulsory notification disease in the Rio de Janeiro State since 2013 [40]. Afterwards, other Brazilian states, such as Pernambuco, Paraíba, and Minas Gerais as well as the cities of Guarulhos (São Paulo State), São Paulo city (the capital of São Paulo State), Camaçari, and Salvador (Bahia State) also established sporotrichosis as a notifiable disease [41]. However, these measures are still insufficient to estimate and control the epidemic of the disease in Brazil. Moreover, in spite of the inclusion of sporotrichosis in the epizootic list of national notification in 2014 [42], there is still a huge challenge in the practical scenario.

Sporotrichosis transmission profile in Brazil is different from other countries, mainly due to the predominance of zoonotic transmission by domestic cats [4, 9]. In fact, most of the Brazilian cases (79.3%) collected in this systemic review reported cat zoonotic transmission of sporotrichosis. Zoonotic sporotrichosis was also described in others countries, such as the USA, Paraguay, Mexico, Panama, and India, however, with a lower impact in public health [32, 34, 43–46]. The main case series related to cat transmission outside Brazil was described in a referral center in Malaysia, where 19 cases were diagnosed through six years (2004 to 2010) [47]. Besides, in Argentina, 16 human cases reported scratches, bites, or contact with exudates from sick cats with sporotrichosis [48]. In Europe and Australia, although feline sporotrichosis cases exist, cat transmission is not reported [49, 50].

In Brazil, the zoonotic transmission is related to S. brasiliensis which is the predominant species identified in the national territory [16, 51]. Outside Brazil, S. brasiliensis was described in Argentina where it has been isolated from human, animal, and environment sources since 1986, and cat transmission was also reported in this country [33]. Rio Grande do Sul one of the Brazilian states presenting the highest numbers of sporotrichosis cases identified in this review borders Argentina, suggesting a common ancestral among Brazilian and Argentinian S. brasiliensis strains. However, to date, it is still not possible to presume where this species emerged. The development of more molecular studies may increase the knowledge about the distribution of this important species in all Brazilian territory and outside Brazil, as to explore its genetic diversity and phylogenomics.

Regarding disease data gathered in this systemic review, most patients had the diagnosis confirmed by culture (65.29%), the gold standard diagnostic method for sporotrichosis. The positivity on culture was most achieved from skin samples, using biopsy, scraping, and/or lesion exudate (Fig. 5). It is interesting to note that, even though the low sensitivity of histopathology [18, 20], we found 21 patients in this review who were diagnosed only by histological examination (Fig. 4). In addition, the requirement of skin biopsies in sporotrichosis lesions is not mandatory, since, according to our data, other less invasive clinical specimens such as skin scraping and lesion’s exudate have satisfactory odds to yield Sporothrix spp. in culture. However, some clinical forms may not present positive culture, since systemic forms involving osteoarticular, respiratory, and central nervous system are challenging to handle [12, 15, 52].

Recently, some authors developed fast diagnosis of sporotrichosis based on DNA detection using species-specific primers or real-time PCR [53, 54]. The molecular diagnosis in Brazil was seldom used, since only one study reported PCR as a diagnostic method. In this study, five patients had Sporothrix spp. identified from cerebrospinal fluid by a nested PCR targeting the 18S rRNA gene [55]. This finding reflects how molecular tools for sporotrichosis diagnosis are still far from implementation in Brazil. In contrast, serological tests were important tools used to diagnose many sporotrichosis cases (10.65%). These tests are helpful to the diagnosis, especially for systemic or atypical clinical forms of this infection, and they are invaluable in cases where skin lesions are absent [20, 24, 27, 56].

Lymphocutaneous and fixed cutaneous forms were the main clinical presentations found in Brazil, as previously described [36, 57], as reported in other countries, such as Mexico [58], China [59], and South Africa [60]. In contrast, in this systematic review, 784 patients (14.34%) presented systemic involvement, probably representing the major casuistry of disseminated sporotrichosis reported so far. In Mexico, from 1914 to 2019, disseminated sporotrichosis was observed in 3.43% of cases [58], and in China, only the disseminated cutaneous form is reported [61]. This finding may be biased by the fact that authors usually tend to publish unusual and severe cases of diseases. Most of the systemic presentations of sporotrichosis evaluated in this review were characterized by pulmonary involvement. Pulmonary sporotrichosis is not usually described in the global literature. However, Falcão et al. described 223 pulmonary sporotrichosis cases related to hospitalizations and deaths in Brazil [41]. One fatal case due to S. brasiliensis pulmonary sporotrichosis in an immunocompetent patient from the Northeast region of Brazil was also described [12].

In this systematic review, 249 patients (4.55%) presented immunoreactive forms. These manifestations are suggested to be associated with S. brasiliensis [62, 63]. However, most immunoreactive cases did not have molecular identification of the agent. As hypersensitivity is an immunological reaction developed by the host, genetic characteristics of Brazilian population may also be implicated in the higher frequency of these presentations in the country epidemics. Finally, the highest numbers of cases in Brazilian hyperendemia of sporotrichosis may increase the probability of occurrence of these atypical cases. For instance, in Argentina, where S. brasiliensis also occurs in lower frequency, immunoreactive forms were not described [48].

Most of the severe sporotrichosis cases reported in the literature are related to systemic forms, such as the involvement of the central nervous system in HIV-coinfected patients with low CD4 [41, 64]. We identified 156 cases of sporotrichosis (16.9%) in people living with HIV/AIDS. It was not possible to calculate the mortality rate in this group of patients, since some studies did not report the clinical outcomes. In addition, most studies do not present the immunologic status of the patients, hampering the knowledge about the association between sporotrichosis and immunodeficiency. One Brazilian study showed that 32.3% of deaths were related to HIV-Sporothrix coinfection [41]. In the USA, the major risks observed for hospitalizations associated with sporotrichosis were HIV/AIDS, immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Other important risk factors that impacts on sporotrichosis prognosis are alcoholism and no-HIV related immunosuppressive conditions, such as those related to organ transplantation, long-term corticosteroid therapy, and neoplasia [41]. Sporotrichosis is not the usual infectious disease in these cases, but the patients may develop severe forms. In this review, twelve patients that receive solid-organ transplantations, mostly kidneys, were identified. Nine of them had outcome reported with two deaths [65, 66].

Sporotrichosis treatment is a challenge for both human and animals. The major drug used for sporotrichosis treatment is itraconazole, used in 63% of cases studied in our review. In other Latin American countries, such as Mexico, Peru, and Colombia, potassium iodide is most frequently used [58, 67, 68], as well as in China [59, 61, 69]. In this review, 30% of the patients were treated exclusively with potassium iodide. The broad use of itraconazole to treat sporotrichosis in Brazil is probably associated with public health policies, since the Brazilian Health System distributes this drug, free of charge, for patients with sporotrichosis. Cryosurgery and local thermotherapy are the main alternative treatments for immunocompetent patients with localized lesions who cannot receive the conventional drug or do not respond to the treatment [20, 29, 31]. These therapies were commonly used in association with antifungal drugs (47.3%), as adjuvant strategies. Outside Brazil, there are few reports about these treatment options [59].

Most animal sporotrichosis cases reported in Brazil occurred in cats. Although most current Brazilian cases of zoonotic transmission to humans are related to domestic cats, the first zoonotic transmission of this mycosis occurred after a rat bite, in São Paulo, Brazil in 1905 [39]. Almeida et al. reported the first cat-transmitted human case of sporotrichosis in Brazil in 1955, when they described a series of 344 cases from a Hospital in São Paulo [36]. In 1989, also in São Paulo, another feline case of sporotrichosis with transmission to the owner and the veterinary was reported [70]. In the late 1990s, some zoonotic cases started to be reported in Rio de Janeiro State [71, 72]. In this century, the number of sporotrichosis cases has increased exponentially, mainly in the South and Southeast Brazil, hampering the disease control. Moreover, ongoing geographical expansion of sporotrichosis to many Brazilian states that did not report feline cases and zoonotic transmission in the early 2000s is evident [4, 9]. The Brazilian scenario may reflect many complexes social and environmental conditions combined with a historical negligence towards the prevention of endemic fungal diseases, contributing to the inability to control the spread of the disease.

According to the One Health approach, human-animal-environmental health are equivalent and connected [73]. Therefore, it is reasonable to think that animal sporotrichosis and environmental conditions in Brazil are the main key to reduce case numbers and control the disease. The most affected areas by sporotrichosis in Brazil have low basic sanitary conditions, accumulation and inadequate disposal of waste as well as human actions disturbing the environment in urban areas [74–77]. Additionally, this emerging disease represents an important indicator of socio-environmental vulnerability in Argentina and Brazil, and therefore, it is fundamental to develop measures to mitigate the social and environmental impact [48]. It is equally important to provide treatment to sick animals, since it has been demonstrated that sick cats receiving proper antifungal treatment present a significant reduction in their fungal burden, reducing transmission, the potential capacity of disease spread [78], and cat mortality, as high as 24.3% detected in this study. In addition, a control of the high demographic density of feline populations in urban cities is necessary. Most of reviewed feline sporotrichosis cases (67.13%) occurred in non-sterilized animals, reflecting the poor population control, which facilitates the propagation of the disease promoted by the cat behavior [76, 79, 80]. Sporotrichosis is present in almost all Brazilian territory, and zoonotic transmission have been reported in many Brazilian states; then a national campaign is needed, to organize the control of the disease which has been spreading to more areas.

Furthermore, few studies recovered Sporothrix spp. from the environment, which impairs the knowledge of the sporotrichosis eco-epidemiology in Brazil. In many countries, Sporothrix spp. have been isolated from natural sources, and the major identified species was S. schenckii, whereas S. brasiliensis and S. globosa, the other two clinical relevant species, were rarely found in the environment [81]. In Brazil, Sporothrix spp. was isolated from organic matter traditionally associated with the fungus and from places where cats with sporotrichosis lived, showing both zoonotic and sapronotic roles in the potential dissemination of the fungus [82]. Sporothrix spp. was also isolated from cats’ feces in a sand heap [76] and in mice’s feces from an experimental model of systemic sporotrichosis [53]. These findings also support the progress of the epidemic because infected animals may disperse the agents of sporotrichosis to the environment, contaminating new areas with the fungus [76].

This systematic review has some limitations, mainly missing demographic and clinical of patients, as well as molecular identification of Sporothrix species in several papers, perhaps influencing in the perception of the true face of sporotrichosis in Brazil. Moreover, it hindered some associations, such as analysis between outcome and clinical forms or outcome and treatment. These articles containing incomplete information about clinical aspects of sporotrichosis were included in this review because if only complete articles containing all information were included, several cases would be missing and the answer to the major questions of this work would be strongly biased. Another limitation was the difficulty to classify the clinical forms based on the variety of clinical presentations reported by the authors. Therefore, in order to standardize the description of clinical forms, we opted to adapt previous classifications to the most recent proposed one [20].

Lastly, most of cases reported were concentrated in South and Southeast of Brazil, which can also be related to the greater number of research center in these areas. In general, case reports describe special or uncommon cases of the disease, which could have affected the proportion of cutaneous/systemic cases and the true numbers of sporotrichosis in Brazil. Another fact supporting that the cases studied here are the tip of the iceberg of sporotrichosis in Brazil is that several papers report molecular identification and/or antifungal susceptibility of Sporothrix strains without presenting clinical data associated with the strains [83–86]. For the purposes of this systematic review, they were discarded, because our main intention was to describe the burden of the disease. It is of great importance that future studies correlate clinical and laboratorial data, in order to contribute to the management of sporotrichosis and to translate the scientific knowledge into practice.

In conclusion, sporotrichosis is an endemic subcutaneous mycosis in Brazil, especially the South and Southeast regions, ongoing expansion to all Brazilian states. The zoonotic transmission by cats has been contributing to this progressive increasing numbers of cases. The usual reported clinical form of the disease was lymphocutaneous, although many systemic cases were described with emphasis on pulmonary sporotrichosis. Finally, this study gathers the main aspects about human and animal sporotrichosis in Brazil, which should not be thought independently in zoonotic scenario.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Angelina Silva and Alessandra Pinheiro for their help in the search at Manguinhos Library.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Vanessa Brito de Souza Rabello, Marcos de Abreu Almeida, Andrea Reis Bernardes-Engemann, Rodrigo Almeida-Paes, Priscila Marques de Macedo, and Rosely Maria Zancopé-Oliveira. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Vanessa Brito de Souza Rabello, Marcos de Abreu Almeida, Andrea Reis Bernardes-Engemann, Rodrigo Almeida-Paes, Priscila Marques de Macedo, and Rosely Maria Zancopé-Oliveira, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

RMZ-O was supported in part by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico [CNPq 302796/2017–7] and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro [FAPERJ E-26/202.527/2019]. We also thank the support given by Fundação Oswaldo Cruz.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are presented within the manuscript and/or its supplementary data.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable. This article does not contain any studies with human participants and/or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Not applicable. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest/Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chakrabarti A, Bonifaz A, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Mochizuki T, Li S. Global epidemiology of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol. 2015;53:3–14. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myu062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marimon R, Cano J, Gene J, Sutton DA, Kawasaki M, Guarro J. Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3198–3206. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00808-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigues AM, Cruz Choappa R, Fernandes GF, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Sporothrix chilensis sp. nov. (Ascomycota: Ophiostomatales), a soil-borne agent of human sporotrichosis with mild-pathogenic potential to mammals. Fungal Biol. 2016;120:246–264. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigues AM, Terra Della PP, Gremião ID, Pereira SA, Orofino-Costa R, de Camargo ZP. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:813–842. doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valeriano CAT, de Lima-Neto RG, Inácio CP, de Souza Rabello VB, Oliveira EP, Zancopé-Oliveira RM, et al. Is Sporothrix chilensis circulating outside Chile? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon DM, Salkin IF, Duncan RA, Hurd NJ, Haines JH, Kemna ME, et al. Isolation and characterization of Sporothrix schenckii from clinical and environmental sources associated with the largest U.S. epidemic of sporotrichosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1106–1113. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.6.1106-1113.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuinness SL, Boyd R, Kidd S, McLeod C, Krause VL, Ralph AP. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of cutaneous sporotrichosis, Northern Territory. Australia BMC Infect Dis. 2015;16:16. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gremião IDF, Miranda LHM, Reis EG, Rodrigues AM, Pereira AS. Zoonotic epidemic of sporotrichosis: cat to human transmission. PLoS Pathogens. 2017;13(1):e100607. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gremião IDF, Oliveira MME, Monteiro de Miranda LH, Saraiva Freitas DF, Pereira AS. Geographic expansion of sporotrichosis, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:621–624. doi: 10.3201/eid2603.190803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodrigues AM, de Melo Teixeira M, de Hoog GS, Schubach TMP, Pereira SA, Fernandes GF, et al. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a high prevalence of Sporothrix brasiliensis in feline sporotrichosis outbreaks. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singhai M, Rawat V, Verma P, Jha PK, Shree D, Goyal R, et al. Primary pulmonary sporotrichosis in a sub-Himalayan patient. J Lab Physicians. 2012;4:048–49. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.98674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.do Monte Alves M, Pipolo Milan E, da Silva Rocha WP, de Sena da Costa AS, Araújo Maciel B, Cavalcante Vale PH, et al. Fatal pulmonary sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis in northeast Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Hagen F, Stielow B, Rodrigues AM, Samerpitak K, Zhou X, et al. Phylogeography and evolutionary patterns in Sporothrix spanning more than 14 000 human and animal case reports. Pers - Int Mycol J. 2015;35:1–20. doi: 10.3767/003158515X687416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira LC, Oliveira MME, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Nosanchuk JD. Zancopé-Oliveira RM (2015) Phenotypic characteristics associated with virulence of clinical isolates from the Sporothrix complex rodrigo. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2015/212308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freitas DF, Santos SS, Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira MM, do Valle AC, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, et al. Increase in virulence of Sporothrix brasiliensis over five years in a patient with chronic disseminated sporotrichosis. Virulence. 2015;6:112–120. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2015.1014274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Della Terra PP, Rodrigues AM, Fernandes GF, Nishikaku AS, Burger E, de Camargo ZP (2017) Exploring virulence and immunogenicity in the emerging pathogen Sporothrix brasiliensis. Xue C, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11:e0005903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cruz ILR, Freitas DFS, de Macedo PM, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, do Valle ACF, Almeida M de A, , et al. Evolution of virulence-related phenotypes of Sporothrix brasiliensis isolates from patients with chronic sporotrichosis and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Braz J Microbiol. 2021;52:5–18. doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zancope-Oliveira RM, Almeida-Paes R, Oliveira MME, Freitas DF, Gutierrez Galhardo, Maria Clara (2011) New diagnostic applications in sporotrichosis. Skin Biopsy - Perspectives. InTech. p. 336.

- 19.Zancope-Oliveira RM, Almeida-Paes R, Ruiz-Baca E, Toriello C. Diagnosis of sporotrichosis: current status and perspectives. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orofino-Costa R, de Macedo PM, Rodrigues AM, Bernardes-Engemann AR. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:606–620. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.2017279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutierrez-Galhardo M, Barros M, Schubach A, Cuzzi T, Schubach T, Lazera M, et al. Erythema multiforme associated with sporotrichosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2005;19:507–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arinelli A, do Cuoto Aleixo ALQ, Freitas DFS, do Valle ACF, Almeida-Paes R, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, et al. Ocular sporotrichosis: 26 cases with bulbar involvement in a hyperendemic area of zoonotic transmission. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28:764–771. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1624779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lima Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clinical Microbiology Review. 2011;24:633–654. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernardes-Engemann AR, Costa RCO, Miguens BR, Penha CVL, Neves E, Pereira BAS, et al. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the serodiagnosis of several clinical forms of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol. 2005;43:487–493. doi: 10.1080/13693780400019909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almeida-Paes R, Pimenta MA, Pizzini CV, Monteiro PCF, Peralta JM, Nosanchuk JD, et al. Use of mycelial-phase Sporothrix schenckii exoantigens in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of sporotrichosis by antibody detection. CVI. 2007;14:244–249. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00430-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa RO, de Macedo PM, Carvalhal A, Bernardes-Engemann AR. Use of potassium iodide in dermatology: updates on an old drug. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:396–402. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bunce PE, Yang L, Chun S, Zhang SX, Trinkaus MA, Matukas LM. Disseminated sporotrichosis in a patient with hairy cell leukemia treated with amphotericin B and posaconazole. Med Mycol. 2012;50:197–201. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.584074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paixão AG, Galhardo MCG, Almeida-Paes R, Nunes EP, Gonçalves MLC, Chequer GL, et al. The difficult management of disseminated Sporothrix brasiliensis in a patient with advanced AIDS. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12:16. doi: 10.1186/s12981-015-0051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira CP, Galhardo MCG, Valle ACF. Cryosurgery as adjuvant therapy in cutaneous sporotrichosis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15:181–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa RO, Bernardes-Engemann AR, Azulay-Abulafia L, Benvenuto F, de Lourdes PalermoNeves M, Lopes-Bezerra LM. Sporotrichosis in pregnancy: case reports of 5 patients in a zoonotic epidemic in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:995–998. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000500020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fichman V, do Valle ACF, Freitas DFS, Sampaio FMS, Lyra MR, de Macedo PM, et al. Cryosurgery for the treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis: experience with 199 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1541–1542. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García Duarte JM, Wattiez Acosta VR, Fornerón Viera PML, Aldama Caballero A, Gorostiaga Matiauda GA, Rivelli de Oddone VB, et al. Sporotrichosis transmitted by domestic cat. A family case report Rev Nac (Itauguá) 2017;9:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Córdoba S, Isla G, Szusz W, Vivot W, Hevia A, Davel G, et al. Molecular identification and susceptibility profile of Sporothrix schenckii sensu lato isolated in Argentina. Mycoses. 2018;61:441–448. doi: 10.1111/myc.12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Etchecopaz AN, Lanza N, Toscanini MA, Devoto TB, Pola SJ, Daneri GL, et al. Sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis in Argentina: case report, molecular identification and in vitro susceptibility pattern to antifungal drugs. Journal de Mycologie Médicale. 2020;30:100908. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.100908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almeida F, Sampaio SAP, Lacaz C da S, Fernanades J de C (1955) Dados estatísticos sobre a Esporotricose. Aná1ise de 344 casos. X Reunião anual dos Dermato-sifilógrafos Brasileiros, Curitiba. [PubMed]

- 37.Castro LG, Belda Júnior W, Cucé LC, Sampaio SA, Stevens DA. Successful treatment of sporotrichosis with oral fluconazole: a report of three cases. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:352–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appenzeller S, Amaral TN, Amstalden EMI, Bertolo MB, Neto JFM, Samara AM, et al. Sporothrix schenckii infection presented as monoarthritis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:926–928. doi: 10.1007/s10067-005-0095-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lutz A, Splendore A. Sobre uma micose observada em homens e ratos: contribuição para o conhecimento das assim chamadas esporotricoses. Revista Médica de São Paulo. 1907;21:443–450. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rio de Janeiro (Estado). Secretaria de Estado de Saúde Resolução SES No 674 DE 12/07/2013. Diário Oficial [do] Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2013.8p. [Portuguese]. http://www.rio.rj.gov.br/dlstatic/10112/4364979/4115670/ResolucaoSESN674DE12.07.2013.pdf. Accessed 07 september 2021.

- 41.Falcão EMM, de Lima Filho JB, Campos DP, Valle ACF, do Bastos FI, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, et al. Hospitalizações e óbitos relacionados à esporotricose no Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2019;35:e00109218. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00109218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria GM/MS nº 1.271 de 6 de junho de 2014. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, 2014. 6p. [Portuguese] https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2014/prt1271_06_06_2014.html. Accessed 07september 2021.

- 43.Bove-Sevilla P, Mayorga-Rodríguez J, Hernández-Hernández O. Sporotrichosis transmitted by a domestic cat. Case report Medicina Cutánea Ibero-Latino-Americana. 2008;36:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yegneswaran PP, Sripathi H, Bairy I, Lonikar V, Rao R, Prabhu S. Zoonotic sporotrichosis of lymphocutaneous type in a man acquired from a domesticated feline source: report of a first case in southern Karnataka, India. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1198–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.04049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rees RK, Swartzberg JE. Feline-transmitted sporotrichosis: a case study from California. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rios ME, Suarez J, Moreno J, Vallee J, Moreno JP. Zoonotic sporotrichosis related to cat contact: first case report from Panama in Central America. Cureus. 2018;10:e2906. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang MM, Tang JJ, Gill P, Chang CC, Baba R. Cutaneous sporotrichosis: a six-year review of 19 cases in a tertiary referral center in Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:702–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Etchecopaz A, Toscanini MA, Gisbert A, Mas J, Scarpa M, Iovannitti CA, et al. (2021) Sporothrix brasiliensis: a review of an emerging South American fungal pathogen, its related disease, presentation and spread in Argentina. J Fungi (Basel). 26;7(3):170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Scheufen S, Strommer S, Weisenborn J, Prenger-Berninghoff E, Thom N, Bauer N, et al. Clinical manifestation of an amelanotic Sporothrix schenckii complex isolate in a cat in Germany. JMM. 2015 doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.000039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomson J, Trott DJ, Malik R, Galgut B, McAllister MM, Nimmo J, et al. An atypical cause of sporotrichosis in a cat. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2019;23:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arrillaga-Moncrieff I, Capilla J, Mayayo E, Marimon R, Mariné M, Gené J, et al. Different virulence levels of the species of Sporothrix in a murine model. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:651–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duani H, Palmerston MF, Rosa Júnior JF, Ribeiro VT, Alcântara Neves PL. Meningeal and multiorgan disseminated sporotrichosis: a case report and autopsy study. Medical Mycology Case Reports. 2019;26:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP (2015) Molecular diagnosis of pathogenic Sporothrix species. Vinetz JM, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0004190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Zhang M, Li F, Li R, Gong J, Zhao F (2019) Fast diagnosis of sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix globosa, Sporothrix schenckii, and Sporothrix brasiliensis based on multiplex real-time PCR. Reynolds TB, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13:e0007219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Oliveira MME, Muniz M de M, Almeida-Paes R, Zancope-Oliveira RM, Freitas AD, Lima MA, et al. (2020) Cerebrospinal fluid PCR: a new approach for the diagnosis of CNS sporotrichosis. Reynolds TB, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14:e0008196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Costa RO, de Mesquita KC, Damasco PS, Bernardes-Engemann AR, Dias CMP, Silva IC, et al. Artritis infecciosa como única manifestación de la esporotricosis: serología de muestras de suero y líquido de la sinovia como recurso del diagnóstico. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2008;25:54–56. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(08)70014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lopes-Bezerra LM, Schubach A, Costa RO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2006;78:293–308. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652006000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toriello C, Brunner-Mendoza C, Ruiz-Baca E, Duarte-Escalante E, Pérez-Mejía A, del Rocío R-M. Sporotrichosis in Mexico. Braz. J Microbiol. 2021;52:49–62. doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00387-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yao L, Song Y, Zhou J, Cui Y, Li S. Epidemiological and clinical comparisons of paediatric and adult sporotrichosis in Jilin Province, China. Mycoses. 2020;63:308–313. doi: 10.1111/myc.13045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vismer HF, Hull PR. Prevalence, epidemiology and geographical distribution of Sporothrix schenckii infections in Gauteng, South Africa. Mycopathologia. 1997;137:137–143. doi: 10.1023/a:1006830131173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Song Y, Li S-S, Zhong S-X, Liu Y-Y, Yao L, Huo S-S. Report of 457 sporotrichosis cases from Jilin province, northeast China, a serious endemic region: report of 457 sporotrichosis cases from China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lima ÍMF, Ferraz CE, Gonçalves de Lima-Neto R, Takano DM. Case report: sweet syndrome in patients with sporotrichosis: a 10-case series. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:2533–2538. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Procópio-Azevedo AC, Rabello VBS, Muniz MM, Figueiredo-Carvalho MHG, Almeida-Paes R, Zancopé-Oliveira RM, Silva JCAL, Macedo PM, Valle ACF, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Freitas DFS. Hypersensitivity reactions in sporotrichosis: a retrospective cohort of 325 patients from a reference hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (2005–2018) Br J Dermatol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/bjd.20646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Freitas DFS, Valle ACF do, da Silva MBT, Campos DP, Lyra MR, de Souza RV, et al. (2014) Sporotrichosis: an emerging neglected opportunistic infection in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Vinetz JM, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Arantes Ferreira GS, Watanabe ALC, Trevizoli NC, Jorge FMF, Cajá GON, Diaz LGG, et al. Disseminated sporotrichosis in a liver transplant patient: a case report. Transpl Proc. 2019;51:1621–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fichman V, Marques de Macedo P, Francis Saraiva Freitas D, Francesconi C, do Valle A, Almeida-Silva FF, Reis Bernardes-Engemann A, et al. Zoonotic sporotrichosis in renal transplant recipients from Rio de Janeiro Brazil. Transpl Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1111/tid.13485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ramírez Soto MC (2015) Sporotrichosis: the story of an endemic region in Peru over 28 years (1985 to 2012). Ratner AJ, editor. PLoS ONE 10:e0127924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Rubio G, Sánchez G, Porras L, Alvarado Z. Esporotricosis: prevalencia, perfil clínico y epidemiológico en un centro de referencia en Colombia. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yao L, Song Y, Cui Y, Zhou J-F, Zhong S-X, Zhao D-Y, et al. Pediatric sporotrichosis in Jilin Province of China (2010–2016): a retrospective study of 704 cases. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2020;9:342–348. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piz052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Larsson CE, de Almeida GonçalvesAraujo MVC, Dagli MLZ, Correa B, Fava Neto C. Esporotricosis felina: aspectos clínicos e zoonóticos. Rev Inst Med trop S Paulo. 1989;31:351–358. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651989000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Lima Barros MB, Schubach TMP, Gutierrez Galhardo MC, de Oliveira Schubach A, Monteiro PCF, Reis RS, et al. Sporotrichosis: an emergent zoonosis in Rio de Janeiro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:777–779. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Lima Barros MB, de Oliveira Schubach A, do Valle ACF, Gutierrez Galhardo MC, Conceição-Silva F, Schubach TMP, et al. Cat-transmitted sporotrichosis epidemic in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: description of a series of cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:529–535. doi: 10.1086/381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yeh H-Y, Chen K-H, Chen K-T. Environmental determinants of infectious disease transmission: a focus on one health concept. IJERPH. 2018;15:1183. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.da Silva MBT, de Mattos Costa MM, da Silva Torres CC, Galhardo MCG, do Valle ACF, de Magalhães MAFM, et al. Esporotricose urbana: epidemia negligenciada no Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2012;28:1867–1880. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2012001000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alzuguir CLC, Pereira SA, Magalhães MAFM, Almeida-Paes R, Freitas DFS, Oliveira LFA, et al. Geo-epidemiology and socioeconomic aspects of human sporotrichosis in the municipality of Duque de Caxias, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between 2007 and 2016. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2020;114:99–106. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trz081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Montenegro H, Rodrigues AM, Dias MAG, da Silva EA, Bernardi F, de Camargo ZP. Feline sporotrichosis due to Sporothrix brasiliensis: an emerging animal infection in São Paulo. Brazil BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:269. doi: 10.1186/s12917-014-0269-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Silva GM, Howes JCF, Leal CAS, Mesquita EP, Pedrosa CM, Oliveira AAF, et al. Surto de esporotricose felina na região metropolitana do Recife. Pesq Vet Bras. 2018;38:1767–1771. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miranda LHM, Silva JN, Gremião IDF, Menezes RC, Almeida-Paes R, Dos Reis ÉG, et al. Monitoring fungal burden and viability of Sporothrix spp in skin lesions of cats for predicting antifungal treatment response. J Fungi (Basel) 2018 doi: 10.3390/jof4030092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schubach TMP, de Oliveira Schubach A, dos Reis RS, Cuzzi-Maya T, Blanco TCM, Monteiro DF, et al. Sporothrix schenckii isolated from domestic cats with and without sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mycopathologia. 2002;153:83–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1014449621732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schubach A, Schubach TMP, de Lima Barros MB, Wanke B. Cat-transmitted sporotrichosis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1952–1954. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.040891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ramírez-Soto MC, Aguilar-Ancori EG, Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Ecological determinants of sporotrichosis etiological agents. J Fungi (Basel) 2018 doi: 10.3390/jof4030095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mattei AS, Madrid IM, Santin R, Silva FV, Carapeto LP, Meireles MCA. Sporothrix schenckii in a hospital and home environment in the city of Pelotas/RS - Brazil. An Acad Bras Ciênc. 2011;83:1359–1362. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652011000400022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Zancopé-Oliveira RM, Monzón A, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M. Antifungal susceptibility profile in vitro of Sporothrix schenckii in two growth phases and by two methods: microdilution and E-test. Mycoses. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oliveira MME, Almeida-Paes R, Muniz MM, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Zancope-Oliveira RM. Phenotypic and molecular identification of Sporothrix isolates from an epidemic area of sporotrichosis in Brazil. Mycopathologia. 2011;172(4):257–267. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oliveira MME, Paula S, Almeida-Paes R, Pais C, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Zancope-Oliveira RM. Rapid identification of Sporothrix species by T3B fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(6):2159–2162. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00450-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ottonelli Stopiglia CD, Magagnin CM, Castrillón MR, Mendes SDC, Heidrich D, Valente P, Scroferneker ML. Antifungal susceptibilities and identification of species of the Sporothrix schenckii complex isolated in Brazil. Med Mycol. 2014;52(1):56–64. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2013.818726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are presented within the manuscript and/or its supplementary data.

Not applicable.