Abstract

Klebsiella variicola is generally known as endophyte as well as lignocellulose-degrading strain. However, their roles in goat omasum along with lignocellulolytic genetic repertoire are not yet explored. In this study, five different pectin-degrading bacteria were isolated from a healthy goat omasum. Among them, a new Klebsiella variicola strain HSTU-AAM51 was identified to degrade lignocellulose. The genome of the HSTU-AAM51 strain comprised 5,564,045 bp with a GC content of 57.2% and 5312 coding sequences. The comparison of housekeeping genes (16S rRNA, TonB, gyrase B, RecA) and whole-genome sequence (ANI, pangenome, synteny, DNA-DNA hybridization) revealed that the strain HSTU-AAM51 was clustered with Klebsiella variicola strains, but the HSTU-AAM51 strain was markedly deviated. It consisted of seventeen cellulases (GH1, GH3, GH4, GH5, GH13), fourteen beta-glucosidase (2GH3, 7GH4, 4GH1), two glucosidase, and one pullulanase genes. The strain secreted cellulase, pectinase, and xylanase, lignin peroxidase approximately 76–78 U/mL and 57–60 U/mL, respectively, when it was cultured on banana pseudostem for 96 h. The catalytically important residues of extracellular cellulase, xylanase, mannanase, pectinase, chitinase, and tannase proteins (validated 3D model) were bound to their specific ligands. Besides, genes involved in the benzoate and phenylacetate catabolic pathways as well as laccase and DiP-type peroxidase were annotated, which indicated the strain lignin-degrading potentiality. This study revealed a new K. variicola bacterium from goat omasum which harbored lignin and cellulolytic enzymes that could be utilized for the production of bioethanol from lignocelluloses.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-021-00660-7.

Keywords: Goat omasum strain, Genome comparison, Klebsiella variicola, Lignocellulose, Molecular docking

Introduction

Lignocellulolytic bacteria consist of a variety of hydrolase enzymes that are responsible for the biodegradation of lignocellulosic materials. These enzymes play a key role in the production of biofuel [1]. Biofuel such as bioethanol production is an alternative strategy to mitigate the global fossil fuel crisis. Like other countries, Bangladesh still depends on fossil fuel for daily transport over vehicles on the road and aviation, which contributes to a significant effect on carbon dioxide emission and global warming. Meanwhile, global warming has had a tremendous impact on agriculture and living conditions in Bangladesh. Only in 2019–2020, more than 1100 people died by electricity produced from the firing blaze of the sky during farming practice on lands. To enlighten the darkness of global warming, the utilization of clean energy or bioenergy is increasing locally. However, biofuel production from lignocellulose is under consideration and may be a promising route to mitigate global warming. The sources of lignocellulolytic enzyme such as cellulase, xylanase, and pectinase have not been declared locally yet. Therefore, aside from using pulp, paper, and textile industries, these enzymes’ production is of great importance to developing sustainable saccharification and fermentation technology [2].

The conversion of biomass to biofuel by microorganisms has gained significant momentum over the last several years [3]. Lignin-degrading strains are capable of reducing the lignin content and enhance the digestibility of cellulose [4, 5]. For efficient saccharification, cellulose hydrogen bonds are required to be disrupted to make it easily accessible for cellulase. However, multiple types of pretreatment strategies were applied to lignocellulose, together with the massive amount of commercial enzymes needed for the efficient degradation of celluloses and hemicelluloses. Therefore, the effective enzyme cocktail required to generate a more economic degradation process renders a cheaper bioethanol production [6]. Energy crops like maize and banana are massively cultivated all over the country especially in the northern part of Bangladesh. These plants are only wasted and discarded after harvesting the fruits, which can be promising lignocellulosic sources or secondary substrates of microorganisms for enzyme production. Therefore, the wasted stem and stalk of maize and banana may produce a large amount of monosaccharides.

Several bacterial strains like Bacillus sp., Brevibacillus sp., Cellulomonas sp., Streptomyces sp., and Pseudomonas sp. can decompose lignocellulose by secreting cellulase, hemicellulase, ligninase, swollenin, and pectinase enzymes [7–12]. These enzymes are extendedly categorized into glycosyl hydrolases (GH), carbohydrate esterases (CE), polysaccharide lyases (PL), and auxiliary activities (CBM) [11]. Lignocellulolytic proteins from thermophiles such as Anoxybacillus sp. and Geobacillus sp. have received considerable attention because of their enzyme stability [13, 14]. Moreover, the ligninolytic activity has been found in bacterial genera Pseudomonas, Cellulomonas, Burkholderia, Sphingomonas, Cupriavidus Aquitalea, Streptomyces, Rhodococcus, Gordonia, Clostridiales, and Bacillus isolated from forest soils [15].

The lignin-degrading enzymes such as peroxidases, laccases, monooxygenases, dioxidases, and phenol oxidases were found in bacterial strains such as Escherichia coli K-12, Thermobifida fusca YX, Rhodococcus jostii RHA1, Streptomyces viridosporus strain T7A, Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), Amycolatopsis sp. 75iv2, Pseudomonas sp. strain YS-1p, Bacillus sp. HSTU-2, Citrobacter sp. HSTU-AAJ4, Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-6, and Enterobacter sp. HSTU-AAH8 [2, 10]. Bacteria affiliated with Klebsiella variicola are ethanol-producing prokaryotes [16]. To date, limited studies reported on the lignocellulose degradation of this group of bacteria. K. variicola–affiliated strains retrieved from untreated wheat straw consortia showed endoglucanase/xylanase activities [17]. Several other members of bacteria, such as Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella Pneumonia, and Klebsiella variicola isolated from the intestine of Diatraea saccharalis larvae, were able to produce cellulolytic enzymes [6]. Moreover, K. variicola has not only lignocellulolytic activities but also has the ability to utilize diverse types of carbohydrates [18]. Klebsiella pneumonia is a common species in the omasum content, feces, and alleyways, but the Klebsiella oxytoca and Klebsiella variicola were the most frequent among isolates from soil and feed crops. It was reported in a similar story that heterogeneity of Klebsiella sp. in rumen content and feces, with a median of 80% [19].

The study was aimed to investigate the pectin-degrading strain biochemical characterization, lignocellulose-degrading enzyme production capacities, and genomic features. The genome investigation of goat intestinal K. variicola’s, CAZyme, ligninolytic enzyme activities, and molecular docking results were underexplored. Here, we described the genomic investigation of a K. variicola bacterium, isolated from fresh goat omasum, which secreted lignocellulose-degrading enzymes. The analyses of whole-genome and housekeeping genes of the K. variicola strain HSTU-AAM51 suggested that the strain has markedly deviated from homologs K. variicola strains. In addition, the presence of CAZYyme gene details in the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 genome leads us to hypothesize that the strain might secrete CAZyme and ligninolytic enzymes to degrade lignocellulose in goat omasum as well as facilitates grass or other feed crops for nitrogen fixation in the environment.

Materials and methods

Omasum contents sampling and isolation

The goat omasum from a freshly slaughtered goat was collected from the town meat market at Bahadurbazar (25.6263° N; 88.6333° E), Dinajpur. The sample was transported immediately to the laboratory of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Basherhat nearby Dinajpur, under sterile conditions. Appropriate dilutions (10−4) and (10−6) of goat omasum contents were spread on agar plates containing 1% yeast extract, 1.5% Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), 1.5% agar, and pH 7.0 and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Bacterial colonies were picked from each plate and streaked on agar plates for further purification. The purified colonies were subjected to Congo red agar media (composition: 0.1% (NH4)2SO4, 0.05%KH2PO4, 0.05%K2HPO4, 0.02%MgSO4.7H2O, 0.01% CaCl2, 0.01% NaCl, 0.1% yeast extract, 1.5% agar, and Congo red 0.5%) for the rapid and sensitive screening test of cellulase producers by observing clear zones [20, 21]. The grown colonies that showed discoloration of Congo red plate were considered cellulose-degrading bacteria and stored for further experiments. Several strains were isolated as cellulose-degrading bacteria. Among these isolates, a strain that showed potentialities was selected for the rest of this study. The strain was identified and named Klebsiella variicola HSTU-AAM51.

Biochemical characterization

The metabolic pattern of the strain was analyzed using different biochemical tests, including MR-VP, KOH string, catalase, oxidase, triple sugar iron (TSI), citrate utilization (CIU), motility indole urease (MIU), urease, and individual sugar fermentation/carbohydrates (dextrose, lactose, maltose, and sucrose) test [21]. The detection of the extracellular hydrolytic enzyme activity of the isolate was done by the agar diffusion method. The strain was grown on different enzyme activity indicator medium to detect cellulase, xylanase, amylase, lignin-degrading, and protease. The bacterial growth indicator medium was prepared in distilled water with carboxymethyl cellulose, xylan, and starch; Casein powder was supplemented as the carbon source. Then, the medium was sterilized at 121 °C with 15 psi for 15 min. The purified colonies were subjected to the specific substrate agar plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h [20–22].

DNA extraction, genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation

The genomic DNA of the HTU-AAM51 strain was extracted using the Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Promega, Madison-Wisconsin, USA) as the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and concentration of the isolated genomic DNA were measured using a DNA spectrophotometer (Promega, Madison-Wisconsin, USA). The whole-genome shotgun sequencing of strain HSTU-AAM51 was performed using pair-end sequencing in an Illumina Miniseq sequencing platform (Illumina, CA, USA). The genomic library was prepared from purified DNA fragments using Nextera XT Library Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Raw sequencing reads were processed by FASTQC v. 10.1. FASTQ ToolKit used the manipulation of FASTQ files including adapter trimming, quality trimming, and length filtering [23]. The appropriate paired reads of length ≥ 30 bp were chosen from the pool of corrected reads and the remaining singleton reads were considered single-end reads according to Li et al. [24]. Next, the paired-end and single-end corrected reads were analyzed in k-mer-based de novo assembly using the SOAPDenovo, version 2.04 [25]. The set of scaffolds with largest N50 was identified by evaluating k-mers in the range 29–99 [25]. Furthermore, the scaffolds were subjected to gap closing by utilizing the corrected paired-end reads. Finally, the resulted scaffolds of length ≥ 300 bp were chosen for assembly [24]. The quality-filtered data (248.95 Mbp data size) was de novo assembled using SPAdes version 3.9.0 into contigs and then scaffolds. The respectively assembled reads were finally merged with Progressive Mauve v.2.4.0 (http://darlinglab.org/mauve/user-guide/reordering.html). The resulting assembled genome was annotated and analyzed using NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) version 4.5, Prokka. The prediction of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and pMLST was conducted by using a bacterial analysis pipeline v 1.0.4 Illumina server (www.illumina.com). The functional prediction of protein-coding genes was accomplished by searching against Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) via the rapid annotations using subsystems technology (RAST) server (https://rast.nmpdr.org/).

Gene bank accession number

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of the strains HSTU-AAM51 has been deposited in the national center for biotechnology information (NCBI) and the obtained accession number is MW674660. The whole-genome datasets generated in this manuscript can be found on NCBI under the Klebsiella variicola HSTU-AAM51 complete genome BioProject number PRJNA594144 and BioSample number SAMN13505812 and accession number WSET00000000, respectively.

Comparative genomic analyses

Phylogenetic tree and average nucleotide identity (ANI)

The sequences of housekeeping genes were acquired from genome data, aligned separately, and concatenated in the following order: 16S rRNA, rpoB, recA, tonB, gyrB. The phylogenetic trees of the 16S rRNA gene and concatenated housekeeping genes were constructed by the neighbor-joining method using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA X). The phylogenetic tree of the HSTU-AAM51 strain along with the whole-genome sequence of the nearest strains was built using REALPHY1.12 online server (http://www.realphy.unibas.ch/realphy/). The JSpeciesWS server (http://jspecies.ribhost.com/jspeciesws) was used to determine the ANI values based on BLAST (ANIb) between strain HSTU-AAM51 and its closely related taxa.

Genome comparison

To reveal the genome features, the HSTU-AAM5 genome was compared with the nearest recently reported genome sequences of Klebsiella species. The circular and linear genomic maps of each genome were generated using Interactive Microbial Genomic Visualization with cGView (http://www.cgview.) and Ring Image Generator (BRIG, version 0.95). Each circular and linear genomic map was generated with BLAST+, with strand parameters (70% lower and 90% upper cutoff for identity and E value of 10), using Klebsiella variicola HSTU-AAM51 as the alignment reference genome. Moreover, the synteny block/genome colinearity of the strain HSTU-AAM51 was analyzed with the nearest homologous genome of Klebsiella variicola strain 13,450, Klebsiella sp. strain P1CD1, Klebsiella variicola strain ACCHC, and Klebsiella variicola strain FDA ARGOS627 using Progressive Mauve server (http://darlinglab.org/mauve/mauve.html). The in silico DNA-DNA hybridization of the Klebsiella variicola strain HSTU-AAM51 with the top fifteen nearest strains was performed in the GGDC server (http://ggdc.dsmz.de).

Carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZy) gene annotation

Essential genes for active carbohydrate enzymes (CAZymes) encoded in the genome of strain HSTU-AAM51 were classified by dbCAN (using HMMER), CAZy (using DIAMOND), and PPR (using Hotpep) databases, respectively, in the integrated dbCAN2 meta server using default settings. The gene functions were investigated by the following different databases: the carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZy) database (http://www.cazy.org/), the KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp.kegg/pathway.html), the non-redundant protein database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/), the gene database (http://www.geneontology.org/), and the clusters of orthologous groups (COG) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/).

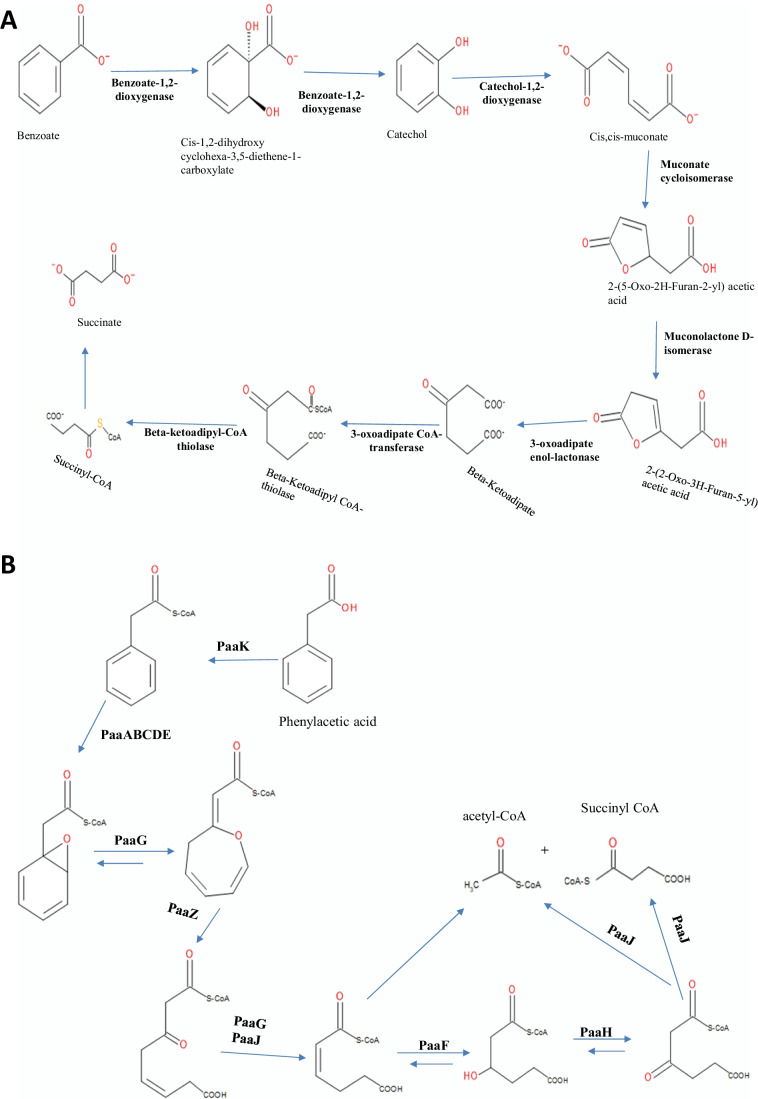

Lignin-degrading pathways

The lignin degradation pathways such as benzoate, phenylacetate, and β-ketoadipate pathway genes of the HSTU-AAM51 strain were screened from the prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline (PGAP) annotation file provided by NCBI. The genes involved in lignin degradation were screened according to previously reported Kumar et al. [26]. The plant growth–promoting genes were screened in a PGAP annotated file according to Guo et al. [27].

Enzyme production on banana fiber

The isolate HSTU-AAM51 was inoculated into the production medium contained 1% (w/v) of banana fiber with yeast extracts and mineral salts [21, 22]. The banana fiber was extracted from the culture after 6 days and dried overnight in an oven at 55 °C. The culture solution was centrifuged at 6000 g for 10 min to separate the debris and cells. The supernatant was used as an enzyme source. The secreted protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method. The crude enzyme solution’s cellulase activity was assayed by measuring the level of reducing sugars liberated from the avicel substrate using the DNS method [28]. The reaction mixture was composed of 0.4 mL of 0.05 M sodium citrate (pH 5.2) buffer with avicel (1%) and 0.1 mL of culture supernatant. The mixture was incubated at 55 °C for 10 min, and then the reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 mL DNS reagent and kept in a boiling water bath for 10 min. For control, the culture supernatant was added after mixing DNS reagents. Then, the solutions were cooled at room temperature, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. One unit of cellulase was considered the amount of enzyme required to release 1 µmol of reducing sugars per minute under the mentioned assay conditions. The xylanase activity was determined by measuring the amount of reducing sugars released from 1% (w/v) oat-spelt xylan as a substrate-like cellulase assay. The pectinase activity was determined by measuring the release of D-galacturonic acid from commercial 1% (w/v) pectin as substrates under the same conditions mentioned for cellulase and xylanase. The lignin peroxidase assay method adapted from Magalaes et al. [29]. The assay mixture contained 3.0 mL: 2.2 mL of supernatant, 0.1 mL of 1.2 mM methylene blue dye, and 0.6 mL of 0.5 M sodium tartrate buffer (pH 4.0). The reaction was started after adding 0.1 mL of 2.7 mM H2O2. The gradually declined absorbance of methylene blue was recorded at 664 nm and the unit of lignin peroxidase was calculated as per the change of absorbance per minute.

Structural analysis and molecular docking of CAZy enzymes

To sort the CAZy enzyme for molecular docking, the signal peptide of the CAZy enzyme was identified using the SignalP5.0 server (www.cbs.dtu.dk). Afterward, the 3D structure of the noncytoplasmic domain–containing enzymes of HSTU-AAM51 strain was built according to the homology modeling in I-TASSER (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/). The 3D structure of CAZy enzymes was evaluated before and after the energy minimization step to assess the quality of the constructed models using several tools provided in the UCLA-DOE server (http://servicesn.mbi.ucla.edu/). The stereochemical quality of each enzyme model was validated by PROCHECK (https://servicesn.mbi. ucla.edu/PROCHECK/) and Varify3D (https://servicesn.mbi.ucla.edu/Verify3D/) to check the atomic model and its amino acid quality. The docking interaction of the signal peptide–containing lignocellulose-degrading twelve enzymes with interested substrates was conducted to validate the binding affinity. Firstly, blind docking was performed using the EDock online server (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/EDock/). Secondly, the molecular docking of the proteins with ligand was confirmed using Auto dock vina, and PyRx. The standard docking was performed by centralizing the ligand in the 3D structure utilizing the default box dimension. The molecular visualization of the docked complex was performed by Pymol software (Schrodinger, LLC, 2010). The protein–ligand interaction was analyzed by Ligplot plus and protein–ligand interaction profiler.

Results

Isolation and characterization of goat omasum strains

The cellulose-degrading bacterial strains were isolated based on the discoloration of the Congo red agar plate. A simple and conclusive idea about a strain can be inferred from biochemical tests. The biochemical tests were conducted immediately after the strain’s isolation. A total of five different pectin-degrading strains were selected and characterized (Fig. S1). The strains Pec-22 and Pec-24 are gram-negative, while the other three strains are gram-positive. All five strains showed catalase and oxidase activities but with varying degrees (Table 1). Importantly, Pec-23 and Pec-24 have degraded methyl red but all others did not. In contrast, none of them was capable of showing positive results in the VP test. Strains Pec-17 and Pec-23 were positive in motility, indole, urease (MIU), whereas strains Pec-22 and Pec-24 were negative in MIU tests. Strain Pec-16 showed positive in the urease test. All strains showed positive activity towards carbohydrates like dextrose, maltose, sucrose, and lactose utilization tests. In addition, carboxymethyl cellulose, oat-spelt xylan, and lignin-related dye utilization were also confirmed by the strain Pec-24/HSTU-AAM51 (Table 1). Based on the biochemical tests, the pectin hydrolytic strains were varied among each other. Importantly, only the Pec-24/HSTU-AAM51 strain was grown on diazinon-enriched media, which suggested that the strain is capable of scavenging insecticides related to toxic chemicals in goat omasum.

Table 1.

Biochemical characterization of pectin-degrading bacterial isolates from goat omasum

| Test | Pec-16 | Pec-17 | Pec-22 | Pec-23 | Pec-24/HSTU-AAM51 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram stain | + Ve | + Ve | -Ve | + Ve | -Ve |

| Catalase | + + | + + + | + + + | + + | + + + |

| Oxidase | + | + | + + + | + + + | + + + |

| Methyl red | - | - | - | + | + |

| VogesProskauer | - | - | - | - | - |

| Triple sugar iron | + | + | + | + | + |

| Citrate utilization test | + | + + + | + + + | + + + | - |

| Motility, indole, urease | -,-, + | + , + , + | -,-,- | + , + , + | -,-,- |

| Maltose | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sucrose | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dextrose | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lactose | - | + | + | + | + |

| Cellulose hydrolysis | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oat-spelt xylan hydrolysis | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lignin hydrolysis | + | + | + | + | + |

| Diazinon | - | - | - | - | + + + |

The lignin hydrolysis was confirmed by the presence of the strain’s growth in lignin-related dye (Congo red, methylene blue, thymol blue, commercial brilliant blue) agar plate and in broth solution

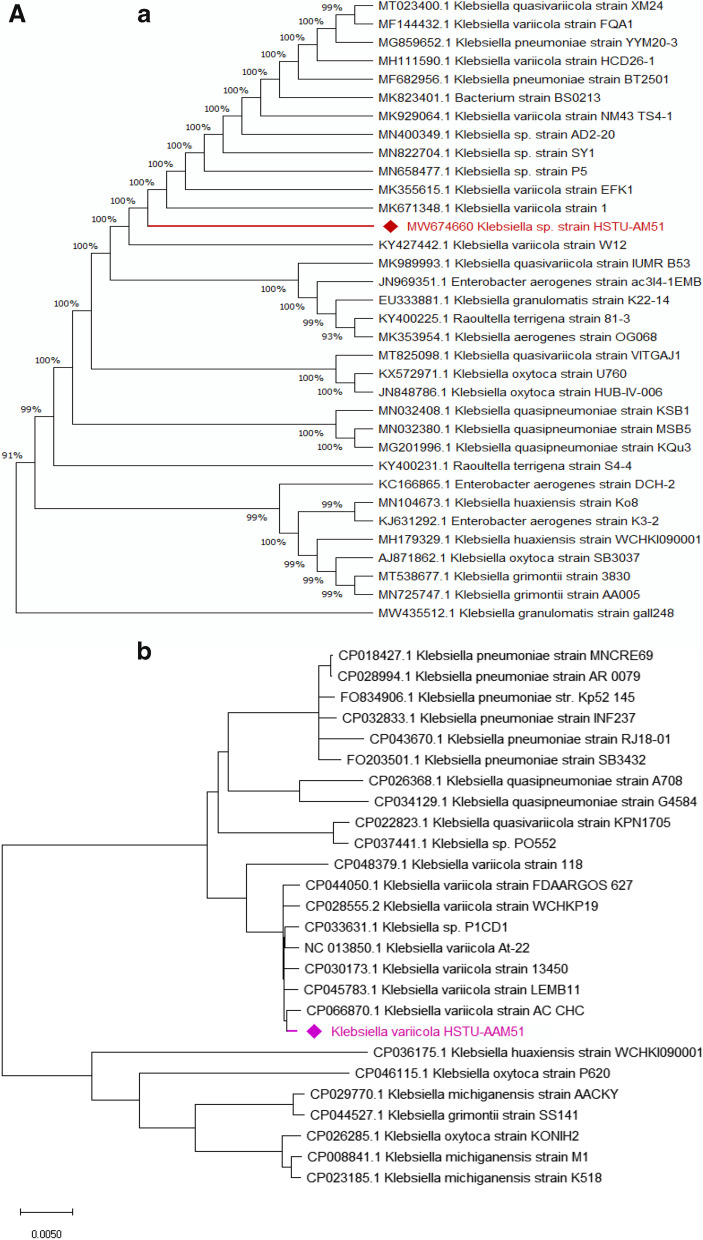

The fastQC analysis of the raw sequence file reported 57.2% that indicated sequence quality was good for further processing of sequence assembly. The MLST analysis confirmed that the strain belonged to the genus Klebsiella variicola. The alignment of housekeeping genes, namely 16S rRNA, tonB, gyrB, and rpoB sequences of the strain HSTU-AAM51, is presented in Fig. 1. Figure 1Aa shows that the gene 16S rRNA has good coverage with K. variicola strain1 (MK671348.1) and K. variicola strain W12 (KY427442.1), but was placed in a separate taxon. Figure 1Ab shows that the whole-genome sequence has also high similarities with K. variicola AC CHC (CP066870.1) and K. variicola LEMB11 (CP045783.1). The phylogenetic tree of whole-genome sequences of HSTU-AAM51 showed that the strain clustered with both K. variicola P1CD1 (CP033631.1) and K. variicola 13,450 (CP030173.1) (Fig. 1Ab). Again, the strain HSTU-AAM51 branches near to other closely related genera, namely, K. grimontii strain SS141 (CP044527.1), K. michiganensis strain AACKY (CP029770.1), K. oxytoca strain P620 (CP046115.1), K. huaxiensis strain WCHKI090001 (CP036175.1), and much far from K. pneumonia (F0203501.1).

Fig. 1.

A (a) Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequence, and (b) a midpoint rooted phylogenetic tree of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain with closely related strains based on whole-genome sequences. All sequences obtained in this study are currently available in the gene bank database. B phylogenetic tree of housekeeping genes: (a) TonB protein, (b) rpoB protein, (c) RecA, (d) DNA gyrase B protein of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain with closely related strains. All the trees were made in MegaX.0 software

The tonB gene has 95% similarities with K. variicola strain E57-7. Moreover, the strain HSTU-AAM51 demonstrated a different cluster with K. variicola At-22 at 0.001 distances. Similarly, the rpoB possessed a separate cluster with K. variicola strain LEMB11, whereas it was placed from the 2nd node of its nearest neighbor’s belongings to K. variicola, and K. variicola KP42C, respectively (Fig. 1Bb). In addition, the recA gene of strain HSTU-AAM51 showed 99% similarities with K. variicola At-22 in a separate cluster (Fig. 1Bc). Similar things were observed for DNA gyrase B since gyrase B of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 placed from the 2nd node of gyrase B of neighbor strains K. variicola At-22 and K. variicola P1CD1, respectively.

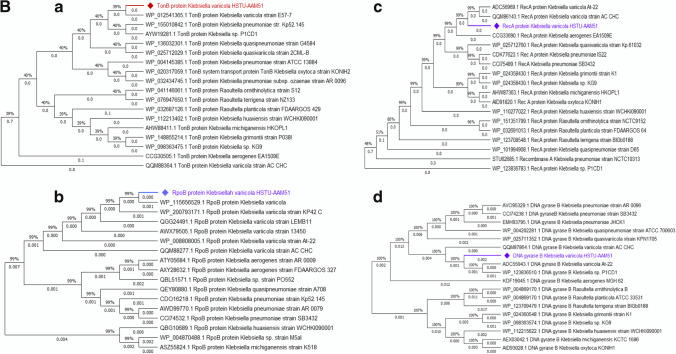

The pairwise ANI blast values between HSTU-AAM51 and K. variicola strain ACCHC were 98.91% (Table 2). K. variicola strain FDA ARGOS 327 and K. variicola strain WCHKP19 showed 98.79% and 98.70% ANIb, whereas other Klebsiella species showed below 90% ANIb, indicating that the strain HSTU-AAM51 might be a new member of K. variicola. The digital DNA-DNA hybridization of the HSTU-AAM51 strain with its nearest homologs showed that except for K. variicola strain 118 (74.5%), all other K. variicola strains showed DDH 92–94% (Table 3), while K. pneumonia related and other Klebsiella species showed 25.7–58.4% DDH.

Table 2.

Average nucleotide identity by Blast (ANIb) analyses of the Klebsiella variicola strain HSTU-AAM51

Table 3.

Digital DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) of Klebsiella variicola strain HSTU-AAM51 with its nearest homologs

| Reference strains genome compared | Formula: 1 (HSP length/total length) DDH | Formula: 2 (identities/HSP length) DDH recommended | Formula: 3 (identities/total length) DDH | Difference in % G + C (interpretation:distinct species) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella aerogenes strain AR0009 | 46.80% | 29.90% | 41.80% | 2.26 |

| Klebsiella grimontii strain SS141 | 48.70% | 27.00% | 42.00% | 1.30 |

| Klebsiella huaxiensisstrain WCHKl | 41.30% | 25.70% | 36.20% | 1.27 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca strain P620 | 46.30% | 26.30% | 39.90% | 3.11 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia str. Kp52.145 | 77.80% | 58.40% | 76.40% | 0.17 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia strain SB3432 | 71.20% | 57.30% | 70.50% | 0.02 |

| Klebsiella quasipneumoniae strain A708 | 79.70% | 52.50% | 76.20% | 0.66 |

| Klebsiella quasivariicola strain KPN1705 | 75.60% | 55.90% | 73.90% | 0.29 |

| Klebsiella variicola P1CD1 | 90.50% | 93.30% | 93.40% | 0.12 |

| Klebsiella variicola At-22 | 91.00% | 93.60% | 93.80% | 0.35 |

| Klebsiella variicola strain 15WZ-82 | 92.40% | 94.00% | 94.90% | 0.18 |

| Klebsiella variicola strain 118 | 88.20% | 74.50% | 88.70% | 0.00 |

| Klebsiella variicola strain 13,450 | 90.90% | 92.90% | 93.60% | 0.20 |

| Klebsiella variicola strain AC CHC | 84.30% | 94.10% | 88.70% | 0.11 |

| Klebsiella variicola strain FDAARGOS_627 | 91.70% | 92.50% | 94.10% | 0.40 |

| Klebsiella variicola strain LEMB11 | 92.90% | 93.40% | 95.10% | 0.30 |

| Klebsiella variicola strain WCHKP19 | 89.90% | 92.70% | 92.90% | 0.32 |

| Klebsiella variicola strain X39 | 88.80% | 93.60% | 92.10% | 0.12 |

Logistic regression is used for reporting the probabilities that DDH is > = 70% and > = 79%. Percent G + C content cannot differ by > 1 within a single species but by < = 1 between distinct species

Genome metrics of strain HSTU-AAM51

The assembly of the genome sequence generated a total of 290 contigs (with PEGs) and the largest contig size obtained 657,932 bp. The total genome size of the strain HSTU-AAM51 was determined to be 5,564,045 bp with a GC content of 57.2%, N50 value 207,699, L50 value 9, 5312 coding sequences, and 102 RNA genes according to PGAP annotation of NCBI. In particular, the strain HSTU-AAM51 has 5150 protein-coding genes. The genome size of HSTU-AAM51 was slightly greater than the strain of K. variicola 13,450 (5,511,705 bp). The GC content of strain HSTU-AAM51 was similarly related to K. variicola strain 13,450 (57.4%), K. variicola strain WCHKP19 (57.6%), K. quasivariicola strain KPN1705 (56.9%), and K. pneumonia subsp. rhinoscleromatis strain SB3432 (57.2), respectively. The RAST analysis of the strain HSTU-AAM51 genome was conducted and described in the subsections below (Fig. 2A). The genomic feature in the subsystem was about 59% genome coverage. A total of 3038 proteins are involved in the subsystem, including 858 proteins were predicted to be involved in carbohydrate metabolism and for about 594 proteins are involved in amino acid metabolism, whereas the nearest relative, K. variicola strain 13,450, has a total of 438 and 432 proteins for carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, respectively. The CGview analysis shows all the proteins of a bacterium in a proper genomic map. We hereby transcribed the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 bacterial protein into a genomic map where 5187 protein-coding sequence (CDS), and 88 tRNAs were shown in 5.5 mbp length sequences. In Fig. 2B, the GC-skew positive indicated that the CDS was present in downstream and the GC-skew negative indicated that the CDS was present in upstream.

Fig. 2.

General features of the genomic organization of Klebsiella variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain. A Features in the subsystem. B Circular map of the complete genome of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain

Comparative genomic analyses

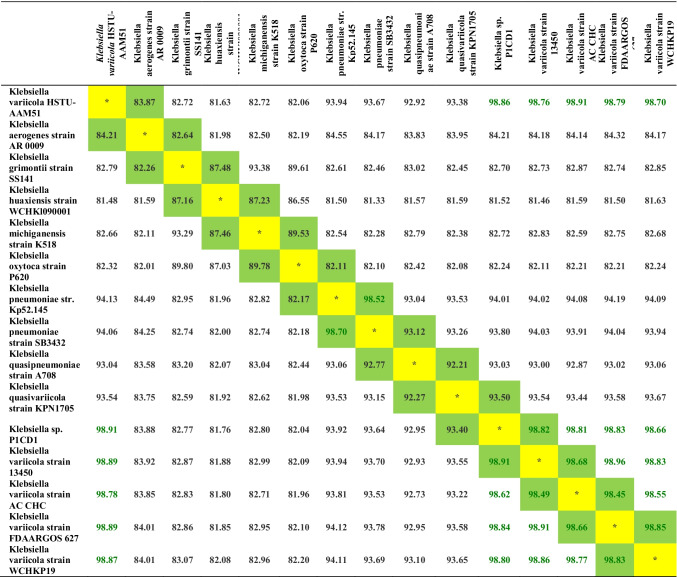

Pangenome analyses

The pangenome graph clearly showed that some parts of the genome sequence of HSTU-AAM51 were unmatched compared to six other strains studied. Specifically, it was focused on the toxin genes in the pangenome study and represented in Fig. 3Aa. The genome sequence of HSTU-AAM51 after 5500 kbp was almost abolished; however, a little irregular homology of genome sequence appeared. The human pathogenicity related genes available in K. pneumonia such as clbJ, clbL, rtlK, gt, gcl, icl, htpB, clpP, ybtA, ybtX, ybtQ, clpX, ybtP, and bet (from 6100 to 7100 kbp) were absent in the K. variicola strain HSTU-AAM51 genome. Interestingly, the top five nearest homologs strain genome comparison (Fig. 3Ab) also showed varied genome assembly.

Fig. 3.

Genomic comparison of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain. A Pangenome analysis of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain with closely related strains. B Synteny analysis of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain with other close related strains. The same color module represents the colinear region. Good colinearity of the strain HSTU-AAM51 and other Klebsiella variicola are shown

Mauve alignment

The block outlines of the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 genome encompassed a sort of sequence that was homologous to part of other genomes compared. It was assumed that the homologous LCBs are internally free from genomic rearrangement of genomes compared. The LCB in the genome of HSTU-AAM51 was connected by lines to similarly colored LCBs in the genomes of P1CD1, 13,450, and FDA ARGOS strains, respectively. The boundaries of LCBs of the HSTU-AAM51 and other strains that have taken comparison are considered break-points of genome rearrangements. As seen in Fig. 3B, the LCBs of the HSTU-AAM51 genome were not exactly matched with LCBs of genomes taken for comparison. A part of the light blue–colored LCB of the HSTU-AAM51 genome was deleted that appeared in other genomes. Moreover, the yellow-colored LCB of the HSTU-AAM51 genome was intact, whereas sorts of sequences are lost from the same colored LCBs of other genomes studied. In addition, the reshuffling or rearrangements of sorts of sequences were found in various LCBs compared to the LCBs of other nearest strain genomes. Interestingly, some LCBs of the K. variicola FDA ARGOS genome were located below the line. These results indicated that this region was inverted compared to the HSTU-AAM51 and other genome sequences studied.

Lignocellulose-degrading enzymes of HSTU-AAM51 strain

A total of 36 CAZy enzymes involved in lignocellulose degradation were observed in the genome of the HSTU-AAM51 strain (Table 4). In particular, a total of seventeen enzymes were categorized as cellulase included GH1, GH3, GH4, GH5, and GH13 families. One cellulase and endoglucanase were found that have non cytoplasmic peptides and used Sec/SPI path for their secretions. Moreover, thirteen different beta-glucosidases (2GH3, 7GH4, and 4GH1) were annotated in the HSTU-AAM51 strain genome. In addition, 6-phospho-alpha-glucosidase, maltodextrin glucosidase, pullulanase type alpha-1,6-glucosidase associated with CBM41 were observed in the genome of the HSTU-AAM51 strain. The pullulanase has shown the signal peptide predicted to use Sec/SPII path. The beta-1,4-mannanase has also contained signal peptide (Sec/SpI), fibronectin type III (FNIII), and carbohydrate-binding module (CBM35) domain. Fifteen different xylanases and mannanases were observed as shown in Table 4. Among them, the hemicellulase, galactosidase, and polysaccharide deacetylase enzymes used Sec/SpI path, whereas glycosyl hydrolase (GH10) used lipoprotein Sec/SpII path of the cell membrane for their secretion (Table 4). Moreover, GH43 family protein xylan 1,4 beta-xylosidase, rhamnogalactouronyl hydrolase, and rhamnosidase were also observed in the genome of HSTU-AAM51. In addition, some β-1,4-mannanase, α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, pectinase, and chitinase belong to the GH18 family protein that holds chitin-binding domain and glycoside hydrolase domain were also annotated in the genome of HSTU-AAM51 strain (Table 4).

Table 4.

List of potential lignocellulose-degrading CAZYzyme found in the genome of Klebsiella variicola strain HSTU-AAM51

| Category | CAZY family | Activities in the family | E.C. number | Locus tag/scaffold | Secretion pathwaysº |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulase | GH3 | Cellulase | 3.2.1.4 | GO309_06680 | Sec/SPI |

| GH5 | Endoglucanase | - | GO309_06640 | Sec/SPI | |

| GH3 | β-glucosidaseBglX | 3.2.1.21 | GO309_13125 | Sec/SPI | |

| GH4 | 6-phospho-alpha-glucosidase | - | GO309_08325 | Others | |

| GH4 | 6-phospho-Beta-glucosidase | 3.2.1.86 | GO309_09810 | Others | |

| GH1 | Beta-glucosidase | 3.2.1.23 | GO309_00745 | Others | |

| GH13 | Maltodextrin glucosidase | 3.2.1.20 | GO309_03805 | Others | |

| GH3 | β-glucosidase | - | GO309_09355 | Others | |

| GH4 | 6-phospho-Beta-glucosidase | 3.2.1.86 | GO309_13085 | Others | |

| GH4 | 6-phospho-Beta-glucosidase | 3.2.1.86 | GO309_18650 | Others | |

| GH4 | 6-phospho-Beta-glucosidase | - | GO309_19150 | Others | |

| GH4 | 6-phospho-Beta-glucosidase | - | GO309_22465 | Sec/SPI | |

| GH4 | 6-phospho-alpha-glucosidase | - | GO309_08325 | Others | |

| GH13/CBM41 | Pullulanase type alpha-1,6-glucosidase | - | GO309_16300 | Sec/SPII | |

| GH13 | Glucohydrolase | - | GO309_24225 | Others | |

| GH1 family | β-glucosidase | - | GO309_20960 | Others | |

| GH1 | Glycoside hydrolase | - | GO309_11750 | Others | |

| GH1 | β-glucosidase | - | GO309_09895 | Others | |

| Xylanase | GH31 | Alpha xylosidase | 3.2.1.177 | GO309_25310 | Others |

| GH4 family | Alpha galactosidase | GO309_14666 | Others | ||

| GH4 family | Alpha galactosidase | - | GO309_21195 | Others | |

| GH53 | Galactosidase | - | GO309_04245 | Sec/SPI | |

| GH42 family | Beta-galactosidase | 3.2.1.23 | GO309_07895 | Others | |

| GH42 family | Beta-galactosidase | - | GO309_04250 | Others | |

| CE4 | Polysaccharide deacetylase | - | GO309_16175 | Sec/SPI | |

| CE4 | Polysaccharide deacetylase | - | GO309_20045 | Others | |

| GH43 family | Beta-xylosidase | - | GO309_26190 | Others | |

| GH43 family | Glycosyl hydrolase | - | GO309_16050 | Others | |

| GH43 family | Xylan 1,4 beta-xylosidase | - | GO309_13940 | Others | |

| GH10 family | Glycosyl hydrolase | - | GO309_08230 | Lipoprotein Sec/SPII | |

| GH105 family | Rhamnogalactouronyl hydrolase | - | GO309_03125 | Others | |

| GH78 family | Rhamnosidase | - | GO309_00360 | Others | |

| Mannanase | GH26/CBM35 | Beta 1,4-Mannanase | - | GO309_09900 | Sec/SPI |

| Chitinase | GH18 | Chitinase | - | GO309_21965 | Sec/SPI |

| Pectin esterase | CE8 | Pectin esterase | Sec/SPII | ||

| Feruloyl esterase | Tannase family | Tannase/Feruloyl esterase | - | GO309_22885 | Sec/SPI |

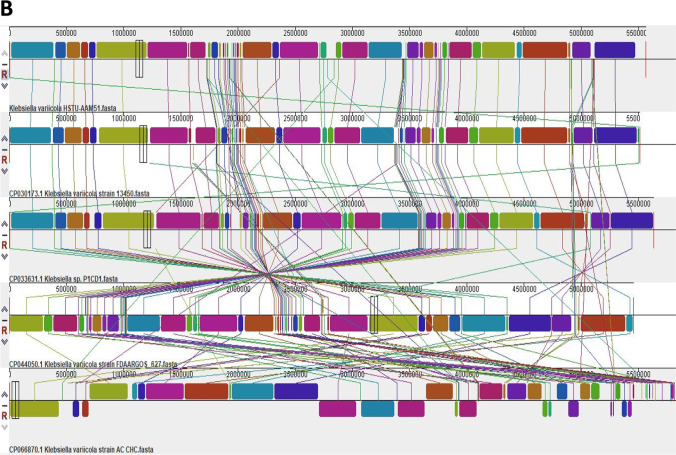

Enzyme secretion

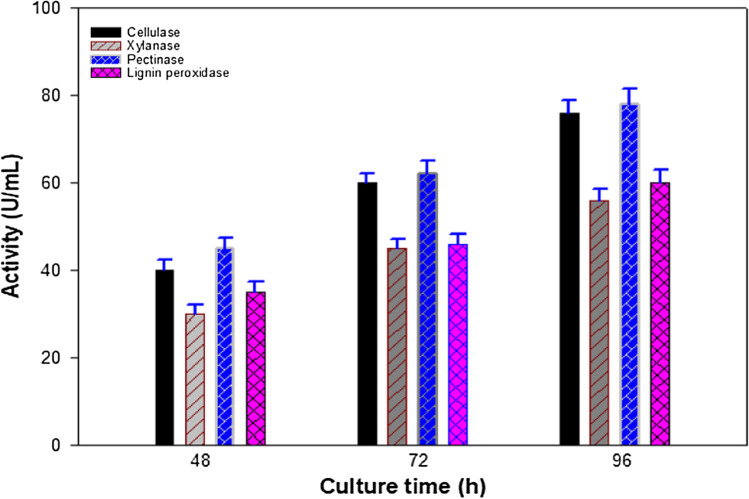

The secretion of lignocellulolytic enzymes such as cellulase, xylanase, pectinase, and lignin peroxidase of HSTU-AAM51 strain was monitored at various incubation periods (Fig. 4). The cellulase and pectinase enzymes had shown higher activities compared to the xylanase and lignin peroxidase at all incubation periods. All tested enzymes showed higher unit activities following increased incubation time as seen (Fig. 4). In particular, the activities of cellulase, xylanase, pectinase, and lignin peroxidase were increased by 1.9-, 1.86-, 1.73-, and 1.7-fold, respectively, after 96 h of incubation in banana pseudostem–enriched media.

Fig. 4.

Lignocellulose-degrading enzyme production by the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain on banana pseudostem. The enzyme production was continued in growth media where banana fiber was used as the sole carbon

source in a shaking incubator at 37° with 140 rpm

Molecular docking of CAZy enzymes with substrate

Homology modeling and assessment

The quality of the protein models obtained from K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 was assessed beforehand. Various factors were taken into consideration including template modeling score (TM), RMSD value, sequence identity, model coverage, structural orientation quality (α-helix, β-sheet, ɳ-coil, unstructured %), overall quality score, compatibility analysis (3D-1D score in %), and Ramachandran plot for amino acid positional quality score analysis (most favorable regions, additionally allowed regions, allowed regions and disallowed regions) (Table 5). Sequence identity and model coverage of the 12 proteins are within an acceptable range (Table 5). All the protein models scored TM values exceeding 0.5 proving their viability (Table 5). The average RMSD of the twelve modeled proteins is 0.87 (less than 1) while 66% of them were below 1.

Table 5.

Model quality of extracellular CAZYzyme of Klebsiella variicola strain HSTU-AAM51

| Model protein | Best PDB hit | TM score; RMSD, Iden.,Cov | α -helix, β-strand, η-coil, π, unstructured (%) | ERRAT (quality score) | VERIFY (3D-1D score)% | Ramachandran plot (core, allow, gener., disallow) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulase GH3 | 4q2b | 0.906; 0.35; 0.534; 0.908 | 42, 12.4, 0.8, 0, 44.7 | 94.98 | 95.9 | 89.4, 9, 0.3, 1.3 |

| Beta-glucosidase | 6r5i | 0.954; 0.68; 0.626; 0.658 | 26.7, 16.7, 4.2, 0.8, 51.6 | 89.17 | 94.3 | 87.6, 10.3, 1.1, 1.1 |

| Galactosidase | 2gft | 0.889; 0.96; 0.407; 0.902 | 26.5, 11.7, 4.7, 0, 57.0 | 82.9 | 92.5 | 80, 17.1, 0.3, 2.6 |

| Endoglucanase | 5czl | 0.944; 0.28; 0.832; 0.946 | 42.6, 6.9, 2.7, 0, 47.7 | 96.9 | 88.6 | 87.7, 9.9, 0.7, 1.7 |

| 6-phospho β-D-glucosidase | 1up7 | 0.913; 1.36; 0.266; 0.939 | 48.1, 15.6, 2.7, 0, 13.4 | 93.04 | 96.4 | 85.9, 12.5, 1.3, 0.3 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase GH10 | 5oq2 | 0.824; 0.52; 0.438; 0.828 | 33.0, 11.8, 5.5, 1.1, 59.5 | 86.73 | 80.0 | 79.1, 16.1, 1.3, 3.5 |

| Mannase | 5awo | 0.792; 1.15; 0.109; 0.803 | 15.2, 7.5, 1.9, 0, 75.3 | 62.5 | 80.0 | 70.3, 21.6, 3.5, 4.6 |

| Pectinase | 3grh | 0.929; 0.21; 0.761; 0.93 | 7.7, 24.8, 2.1, 0, 65.3 | 74.8 | 90.4 | 81.6, 15.2, 1.4, 1.9 |

| Polysaccharide deacetylase | 6go1 | 0.714; 1.48; 0.235; 0.736 | 20.1, 9.3, 1.4, 0, 69.1 | 93.04 | 96.4 | 85.9, 12.5, 1.3, 0.3 |

| Tannase | 6fat | 0.788; 2.36; 0.255; 0.828 | 21.5, 12.8, 4.4, 0, 61.2 | 76.99 | 76.0 | 73.1, 19.3, 3.4, 4.2 |

| Pullulanase | 2fhf | 0.953; 0.41; 0985; 0.955 | 21, 20.6, 5.2, 0, 53.1 | 88.85 | 80.0 | 88.1, 9.6, 1.3, 0.9 |

| Chitinase | 3qok | 0.924; 0.78; 0.95; 0.93 | 27.8, 17.7, 5.2, 0, 49.1 | 97.55 | 90.89 | 85.2, 11.2, 1.7, 1.4 |

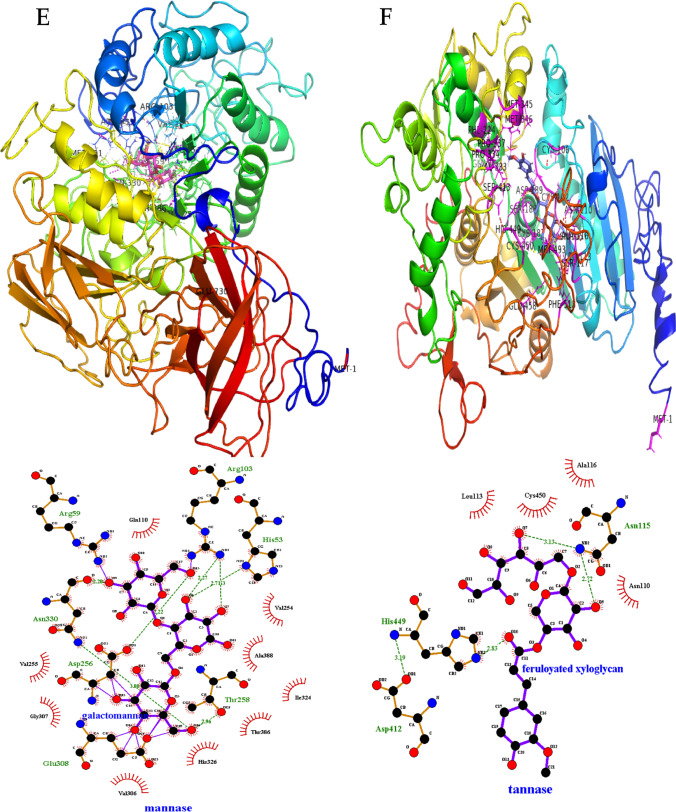

The protein models were fine-tuned using loop refining and energy minimization. The loop-refined and energy-minimized cellulase model protein showed an overall quality factor of 94.9818% and Verify 3D score of 95.93%. The model quality for the other proteins also falls at a satisfactory level. All the protein models except tannase (75.77%) showed above 80.0–96.923% verify 3D score > = 0.2 (Table 5). Protein models for mannase (62.46%), pectinase (74.87%), and tannase (76.98%) demonstrated comparatively lower ERRAT scores while the nine other modeled proteins showed an excellent level (83–97%) of quality for ERRAT in the SAVES server (Table 5).

The Ramachandran plot analysis for cellulase showed 89.4% amino acid residues to be in the most favorable regions, 9% in the additional allowed regions, 0.3% in the generously allowed region, and 1.3% in the disallowed regions. The corresponding values for the best hit cellulase protein (PDB ID: 4q2b) showed 92.2%, 7.4%, and 0.3%, respectively. In addition, beta-glucosidase, endoglucanase, 6-phospho β- D-glucosidase, polysaccharide deacetylase, pullulanase, and chitinase showed above 85% amino acids in the most favorable regions in the Ramachandran plot. Galactosidase and pectinase showed about 80.0% amino acids in the most favorable regions. Moreover, glycosyl hydrolase GH10, mannase, and tannase showed amino acids about 70–79% in the most favorable regions in the Ramachandran plot.

The structural orientation quality (percentage of α-helix, β-sheet, ɳ-coil, the unstructured portion in the protein model, respectively) has also been exhibited (Table 5) which also falls into direct resemblance with the data found in previous articles (mention viable reference). The modeled cellulase for example has a globular structure containing 42%, 12.4%, 0.8%, and 44.7% of α -helix, β-strand, η-coil, and unstructured regions. After considering all possible factors, the modeled proteins were subjected to the next phase which is molecular docking.

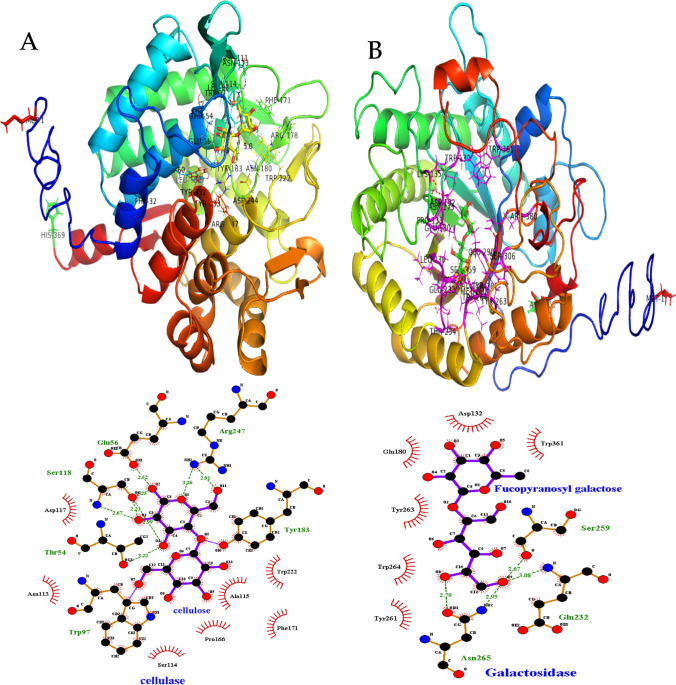

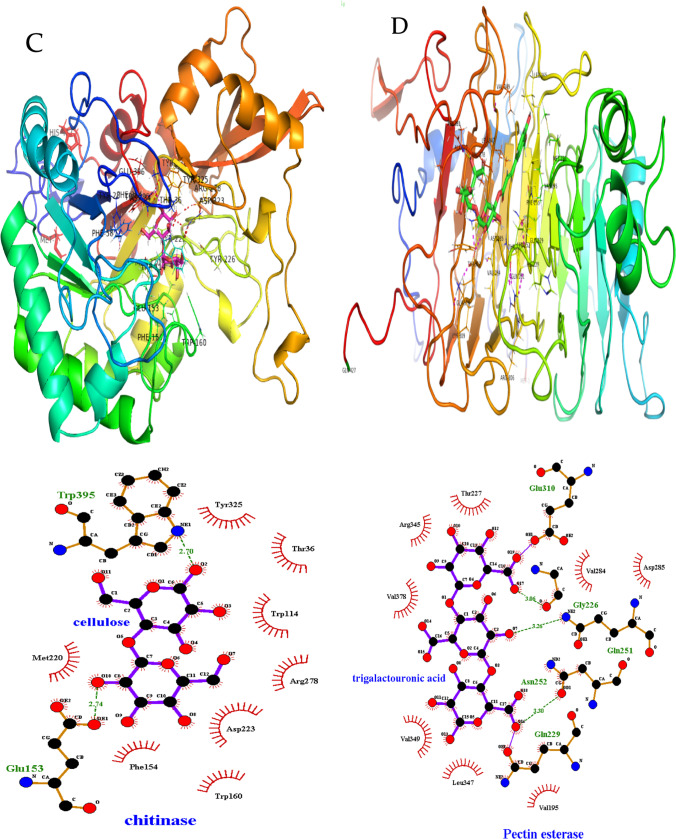

Docking analyses

The best docking complex based on docking score was used to analyze the interaction of enzyme and substrate (Table S1). As seen in Fig. 5A, the cellobiose molecule successfully interacted with the cellulase enzyme. The important catalytic residues of cellulase enzyme include Ser118, Glu56, Arg247, Tyr183, Trp97, and Thr54. These residues have formed H-bonds with cellobiose with an average bond length of 2.23–3.26A°. Moreover, hydrophobic interactions were made by the residues Asp117, Asn113, Ser114, Pro166, Ala115, Phe171, and Trp222 with a maximum bond length of 3.9A°. The β-glucosidase BglX (GH3) residues Arg169, Lys208, Asp287, and Glu518 were interacted with cellobiose through H-bonds, but its residues His288, Met319, Phe81, Met252, trp155, and Trp450 were facilitated hydrophobic interactions with cellobiose ligands (Fig. S2). The other cellulase-type enzyme endoglucanase (GH5), 6-phospho-Beta-glucosidase (GH4), and pullulanase-type alpha-1,6-glucosidase (GH13/CBM41) have shown considerable H-bonds, non-bonded hydrophobic, and salt bridge interactions (Fig. S2). In Fig. 5B, xylanase family enzyme galactosidase has formed H-bonds via residues Ser259, Glu232, and Asn265 with fucopyranosyl galactose. All these important catalytic residues were within 3A° of the ligand. Non-bonded hydrophobic interactions were also made by Asp132, Glu180, Tyr161, Tyr263, Trp264, and Trp361 residues of galactosidase.

Fig. 5.

Molecular docking and catalytic interactions of extracellular signal peptide–containing lignocellulose-degrading enzymes. A Cellulase. B Galactosidase. C Chitinase. D Pectin esterase. E Mannase. F Tannase/feruloyl esterase

The 3D model of pectinase had a folded globular structure consisting of five α-helixes, twenty-five β-strands, and three coils. In particular, cellulose showed the existence of 7.26% α-helixes, 22.7% β-strands, 2.1% coils, and 62.34% non-structured region (Fig. 5D). Structural analysis showed that all catalytically important residues were within 5 Å of the ligands. The binding affinity of feruloyated xyloglucan (FX) was slightly higher than polygalacturonic acid (PGA) as indicated by the docking score (Supplementary Table S1). As seen in Fig. 5F, the Gln229, Gln251, Asn252, Asp285, Glu310, and Gly379 contributed to H-bonds and Arg345 contributed a salt bridge interaction with TGA. In contrast, FX made hydrophobical (Val378), hydrogen bonds (Gln251, Asn381), and salt bridge (Arg345) interactions. The residues Asp285 and Glu310 were found to have bond lengths of 1.86 Å and 3.09 Å, whereas Ser288 was located about 5 Å away from the PGA.

The 3D surface models of tannase (Fig. 5F) consist of 20.82% α-helixes, 12.63% β-strands, 3.75% randon coils, and 64% unstructured regions. The corresponding substrates of the 3D model of tannases were methyl ferulate, feruloyated xyloglucan, and conferyl alcohol. Among these three substrates, the highest docking score and binding affinity were found for feruloyated xyloglucan (Supplementary Table S1).

The endoglucanase showed hydrogen bond interaction (Glu53, Asp104, Ser109, Gly111, Pro158, Tyr175, Trp233, and ASP240) with cellulose (Fig. S2C). The best binding energy was − 6.5 kcal/mole and − 7.0 kcal/mole which was found for cellulase and endoglucanase with cellulose as the substrate. The binding energy indicated superior alignment between the active site residues of cellulase and its corresponding substrates at individual sites shown in Fig. 5A, B, C, D. The docking score for the other cellulase enzymes such as beta-glucosidase, galactosidase, 6-phospho β-D-glucosidase, pullulanase was − 6.6 to − 6.8, − 6.7 to − 6.8, − 5.9 to − 6.5, and − 7.0 to − 8.0 kcal/mole with substrates, namely methyl β-D-galactopyranoside, cellulose, 4-Nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranose, cellobiose, maltose, and maltrose, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

Subsequently, hemicellulase enzyme (glycosyl hydrolase, polysaccharide deacetylase, and mannase) interacted with substrate, namely cellulose, 4-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranose, galactomannan, feruloyated arabinose, feruloyated xyloglucan, and dextrin with free-binding energies ranging from − 7.6 to − 8.3, − 6.5 to − 7.4, and − 7.0 to − 7.1 kcal/mole (Supplementary Table S1). Residues involving possible hydrogen bond interactions are represented in Supplementary Table S1. In addition, chitinase has shown chitin and cellulose-binding interaction with docking scores ranging from − 6.3 to − 6.5 kcal/mole (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Table S1).

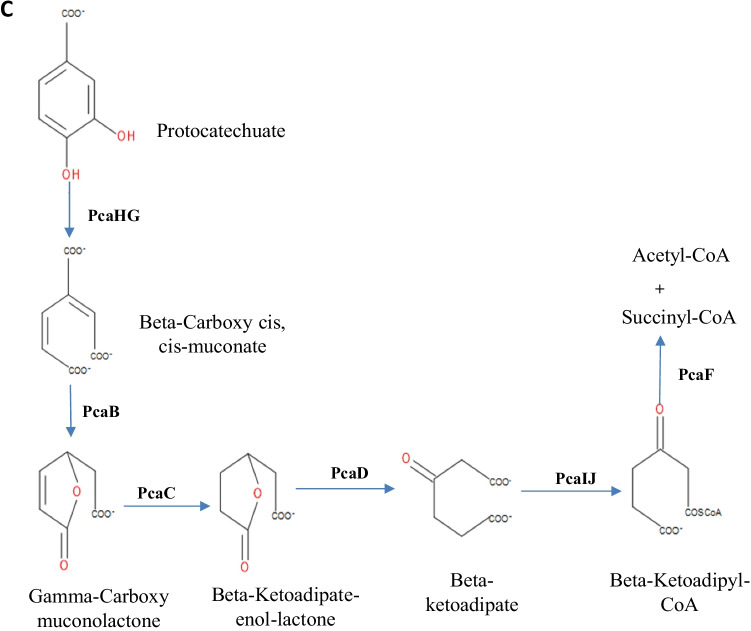

Ligninolytic genetic repertoire

The genes involved in the β-keto adipate pathway are shown in Table 6. In particular, the catechol branch, run by cat gene products, was involved in the conversion of catechol (generated from benzoate), benzene, and some lignin monomers into β-ketoadipate. The pob gene products catalyzed the conversion of 4-hydroxy benzoate to protocatechuate.

Table 6.

Genes encoding the β-ketoadipate pathway and peripheral reactions

| Branch name | Product name | Gene | Locus tag | Ref accession no: | E.C. number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Catechol (cat gene) |

Catechol 1,2-dioxygenase | catA | GO309_00275 | YP_004594166.1 | 1.13.11.1 |

| Muconolactone δ-isomerase | catC | GO309_00280 | YP_004594167.1 | 5.3.3.4 | |

| Muconatecycloisomerase | catB1 | GO309_00285 | YP_004594168.1 | - | |

| Extracellular solute binding receptor protein | catX | GO309_20910 | WP_004124644.1 | - | |

| 3-carboxyethylcatechol 2,3-dioxygenase | mphB | GO309_01715 | WP_016947516.1 | 1.13.11.16 | |

|

Benzoate (ben gene) |

Benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase small subunit | benB | GO309_00265 | YP_004594164.1 | 1.14.12.10 |

| Benzoate/H( +) symporterBenE family transporter | benE | GO309_00615 | WP_004898576.1 | - | |

| 2,3-dihydro-2,3-dihydroxy benzoate dehydrogenase | dhbA | GO309_5240 | YP_004592926.1 | 1.3.1.28 | |

|

4-hydroxy benzoate (pob) gene |

4-hydroxy benzoate 3-monooxygenase | pobA | GO309_17060 | YP_004592293.1 | 1.14.13.2 |

| 4-hydroxybenzoate octaprenyltransferase | - | GO309_22995 | YP_004591886.1 | 2.5.1.39 | |

| DNA-binding response regulator | pobR | GO309_17070 | WP_008807539.1 | - | |

|

Protocatechuate (pca) genes |

LysR family transcriptional regulator | pcaQ | GO309_00455 | WP_019705703.1 | - |

| 4-carboxy muconolactone decarboxylase | pcaC | GO309_17485 | WP_004143067.1 | 4.1.1.44 | |

| 3-oxoadipate enol-lactonase | pcaD | GO309_17490 | WP_012968330.1 | 3.1.1.24 | |

| 3-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate cycloisomerase | pcaB | GO309_17495 | YP_004593823.1 | 5.5.1.2 | |

| 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | pcaF | GO309_17500 | YP_004593822.1 | 2.3.1.174 | |

| 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase subunit B | - | GO309_17505 | YP_004593821.1 | - | |

| 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase subunit A | - | GO309_17510 | YP_004593820.1 | - | |

| Protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase β-subunit | pcaH | GO309_00675 | YP_004594243.1 | 1.13.11.3 | |

| Protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase α-subunit | pcaG | GO309_00680 | YP_004594244.1 | 1.13.11.3 | |

| 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | pcaF | GO309_17860 | YP_17900111.1 | 2.3.1.174 | |

| 2,3-dehydroadipyl-CoA hydratase | GO309_17880 | YP_004594284.1 | 4.2.1.17 | ||

| 4-carboxy-4-hydroxy-2-oxoadipate aldolase | ligK | GO309_25155 | YP_019725153.1 | - |

Benzoate pathway

The strain K. variicola sp. HSTU-AAM51 genome showed gene products of catechol, benzoate, 4-hydroxy benzoate, and protocatechuate branches (Table 7). The pcaQ gene was found in the vicinity of the genes pcaC, pcaD, pcaB, pcaF, pcaH, and pcaG in the genome sequence of the AAM51 strain, which suggested the transcriptional regulation was maintained by the pcaQ gene product in the protocatechuate branch. In this study, two proteins identified 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase subunit B and 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase subunit A, which was located in the pca genes cluster.

Table 7.

Genes encoding catabolic pathways for benzene, toluene, (methyl) phenols, 3-hydroxy phenyl-propionate, and 3-hydroxy anthranilate

| Products name | Genes | Locus tag | Ref accession no | E.C. number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replication initiation negative regulator | seqA | GO309_05745 | YP_004593003.1 | - |

| Putative membrane protein | ymiA | GO309_19345 | WP_002901776.1 | - |

| Transcriptional regulator ChbR | chbR | GO309_19145 | YP_004594490.1 | - |

| Reductase subunit | paaK | GO309_17885 | YP_004594286.1 | - |

| Hydroxylase subunit HpxD | hpxD | GO309_08190 | WP_002904779.1 | - |

| Bacterioferritin-associated ferredoxin | bfd | GO309_25925 | YP_004591201.1 | - |

| Polyphenol oxidase | pgeF | GO309_09130 | YP_004590421.1 | 1.10.3.- |

| Phenolic acid decarboxylase | kpdC | GO309_06850 | YP_004591347.1 | - |

| 3-phenyl-propionate MFS transporter | GO309_18435 | YP_004590381.1 | - | |

| Ferredoxin–NADP( +) reductase | GO309_06005 | YP_004591496.1 | 1.18.1.2 | |

| 2Fe-2S ferredoxin-like protein | GO309_12680 | YP_004595022.1 | - | |

| Pyruvate:ferredoxin (flavodoxin) oxidoreductase | nifJ | GO309_18025 | WP_009486361.1 | - |

| 2-octaprenyl-6-methoxyphenyl hydroxylase | ubiH | GO309_20470 | YP_004590795.1 | 1.14.13.- |

| FAD-dependent 2-octaprenylphenol hydroxylase | ubiI | GO309_20475 | YP_004590794.1 | - |

| 2-octaprenyl-6-hydroxy phenol methylase | GO309_12695 | WP_015959798.1 | - | |

| Catechol 1,2-dioxygenase | catA | GO309_00275 | YP_004594166.1 | 1.13.11.1 |

| 3-(3-hydroxy-phenyl)propionate/3-hydroxycinnamic acid hydroxylase" | GO309_01720 | WP_004891230.1 | 1.14.13.127 | |

| 5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase | hpaE | GO309_1689 | YP_004592265.1 | - |

| 2-hydroxyhepta-2,4-diene-1,7-dioate isomerase | GO309_16900 | YP_004592266.1 | - | |

| 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase | GO309_01255 | WP_004175772.1 | - | |

| 4-hydroxy-2-oxovalerate aldolase | dmpG | GO309_01695 | WP_019705824.1 | 4.1.3.39 |

| Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (acetylating) | dmpF | GO309_01700 | WP_014907417.1 | 1.2.1.10 |

| 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase | GO309_01255 | WP_004175772.1 | - | |

| LysR family transcriptional regulator | GO309_19585 | WP_008805220.1 | - | |

| FAD-dependent 2-octaprenylphenol hydroxylase | ubiI | GO309_20475 | YP_004590794.1 | - |

| acrEF/envCD operon transcriptional regulator | envR | GO309_25365 | WP_008806701.1 | - |

| 3-(3-hydroxy-phenyl)propionate transporter MhpT | mhpT | GO309_01690 | WP_014907419.1 | - |

| 2-keto-4-pentenoate hydratase | mhpD | GO309_01705 | WP_016947515.1 | 4.2.1.80 |

| 2-oxo-hepta-3-ene-1,7-dioic acid hydratase | hpaH | GO309_16880 | YP_004592262.1 | - |

| 3-carboxyethyl catechol 2,3-dioxygenase | mhpB | GO309_01715 | WP_016947516.1 | 1.13.11.16 |

| Transcriptional activator MhpR | mhpR | GO309_01725 | WP_004221425.1 | - |

Phenylacetate pathways

The phenylacetate-degrading (Paa) pathway is involved in the series degradation of phenylacetate. Above, eleven different Paa genes are observed after searching in the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 genome, which encodes for phenylacetic acid degradation (Table 8). Three different transcriptional units such as PaaZ, PaaABCDEFGHIJK, and PaaXY appeared in K. variicola HSTU-AAM51. All these gene clusters were aligned in a row. The existence of the three gene clusters indicates that HSTU-AAM51 can degrade phenylacetate into TCA cycle ingredients acetyl CoA and succinyl CoA.

Table 8.

Genes encoding pathways for phenylacetate, 4-hydroxy phenylacetate, 3-hydroxyl phenyl-propionate, and benzoate proceeding through aryl-CoA intermediates

| Products name | Gene | Locus tag | Ref accession no | E.C. number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylacetic acid degradation protein PaaY | paaY | GO309_17845 | WP_008805114.1 | - |

| Phenylacetic acid degradation operon negative regulatory protein | paaX | GO309_17850 | WP_016947252.1 | - |

| Phenylacetate–CoA ligase | paaF | GO309_17855 | YP_004594279.1 | 6.2.1.30 |

| 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | pcaF | GO309_17860 | YP_004594280.1 | 2.3.1.174 |

| Hydroxyphenylacetyl-CoA thioesterasePaaI | paaI | GO309_17865 | YP_004594281.1 | - |

| 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase | paaH | GO309_17870 | YP_004594282.1 | 1.1.1.35 |

| 2-(1,2-epoxy-1,2 dihydrophenyl) acetyl-CoA isomerase | paaG | GO309_17875 | YP_004594283.1 | |

| 2,3-dehydroadipyl-CoA hydratase | paaD | GO309_17880 | YP_004594284.1 | 4.2.1.17 |

| Phenylacetate-CoA oxygenase/reductase subunit | paaK | GO309_17885 | YP_004594286.1 | - |

| Phenylacetate-CoA oxygenase subunit PaaJ | paaJ | GO309_17890 | YP_004594287.1 | - |

| Phenylacetate-CoA oxygenase subunit PaaC | paaC | GO309_17895 | YP_004594288.1 | - |

| 1,2-phenylacetyl-CoA epoxidase subunit B | paaB | GO309_17900 | YP_004594289.1 | 1.14.13.149 |

| 1,2-phenylacetyl-CoA epoxidase subunit A | paaA | GO309_17905 | WP_020803990.1 | 1.14.13.149 |

| Phenylacetic acid degradation bifunctional protein | paaZ | GO309_17910 | YP_004594291.1 | - |

| 4-hydroxy phenylacetate 3-monooxygenase reductase subunit | hpaC | GO309_16855 | YP_004592257.1 | - |

| 4-hydroxy phenylacetate 3-monooxygenase | hpaB | GO309_16860 | WP_000801462.1 | 1.14.14.9 |

| 4-hydroxyphenylacetate catabolism regulatory protein HpaA | hpaA | GO309_16865 | YP_004592259.1 | - |

| 4-hydroxyphenylacetate permease | hpaX | GO309_16870 | NP_460080.1 | - |

| 4-hydroxy-2-oxoheptanedioate aldolase | hpaI | GO309_16875 | WP_016809283.1 | 4.1.2.52 |

| 2-oxo-hepta-3-ene-1,7-dioic acid hydratase | hpaH | GO309_16880 | YP_004592262.1 | - |

| 5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconate Delta-isomerase | hpaF | GO309_16885 | YP_004592263.1 | 5.3.3.10 |

| 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate 2,3-dioxygenase | hpaD | GO309_16890 | YP_004592264.1 | 1.13.11.15 |

| 5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde dehydrogenase | hpaE | GO309_16895 | YP_004592265.1 | - |

| 2-hydroxyhepta-2,4-diene-1,7-dioate isomerase | hpaG | GO309_16900 | YP_004592266.1 | - |

| 2-hydroxyhepta-2,4-diene-1,7-dioate isomerase | hpaG | GO309_16905 | YP_004592267.1 | - |

| Homoprotocatechuate degradation operon regulator HpaR | hpaR | GO309_16910 | YP_004592268.1 | - |

| O-succinyl benzoate synthase | menC | GO309_12605 | YP_004595037.1 | 4.2.1.113 |

| O-succinylbenzoate–CoA ligase | menE | GO309_12610 | WP_014599221.1 | 6.2.1.26 |

| 3-(3-hydroxy-phenyl)propionate transporter MhpT | mhpT | GO309_01690 | WP_014907419.1 | - |

| 4-hydroxy-2-oxovalerate aldolase | mhpE | GO309_01695 | WP_019705824.1 | 4.1.3.39 |

| Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (acetylating) | mhpF | GO309_01700 | WP_014907417.1 | 1.2.1.10 |

| 2-keto-4-pentenoate hydratase | mhpD | GO309_01705 | WP_016947515.1 | 4.2.1.80 |

| Alpha/beta fold hydrolase | mhpC | GO309_01710 | NP_308431.3 | - |

| 3-carboxyethylcatechol 2,3-dioxygenase | mhpB | GO309_01715 | WP_016947516.1 | 1.13.11.16 |

| (3-hydroxy-phenyl)propionate/3-hydroxycinnamic acid hydroxylase | mhpA | GO309_01720 | WP_004891230.1 | 1.14.13.127 |

| Transcriptional activator MhpR | mhpR | GO309_01725 | WP_004221425.1 | - |

In the HSTU-AAM51 genome, the operons of the 4-hydroxy phenylacetic acid degradation pathway were observed (Table 8). The pathway was composed of hpaBC transcriptional unit (4-HPA hydroxylase), hpaGEDFHI (meta-cleavage), and regulatory genes hpaR and hpaA, respectively. The operons database indicated that HSTU-AAM51 could degrade 4-hydroxy phenylacetic acid into TCA cycle precursors like pyruvate and succinate, while 3-hydroxyl phenyl-propionate–degrading operon genes have existed in the genome of the HSTU-AAM51 strain. From the above analysis, it was therefore assumed that the strain HSTU-AAM51 genome reveals putative genes that encode enzymes leading to ring oxidation and cleavage of lignin and related aromatic compounds via both ortho- and meta-cleavage pathways. Besides, proteins peroxiredoxin, cytochrome oxidase, oxidoreductase, ferredoxin, amino deoxychorismate-lyase, dehydrogenase, acetyl-CoA C-acetyl transferase, enoyl CoA hydratase, glyoxalase, glutaredoxin, alkyl hydroperoxidase, alcohol dehydrogenase, formate dehydrogenase, alkene reductase, GNAT family N-acetyl transferase, glycine betaine/L-proline ABC transporter, etc. are observed in the genome of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51. To further confirm, we have searched additional gene products that are potentially involved in lignin degradation and enlisted them in Supplementary Table S2–5.

Likewise, glycine betaine ABC transporter was also identified in the genome of HSTU-AAM51 (Supplementary Table S2). As seen in Supplementary Table S3, a laccase domain–containing protein was observed. Besides, a total of 23 different types of oxidoreductases including GMC family genes were annotated (Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, 13 different NADH-Quinone oxidoreductase subunits were observed in an operon (Supplementary Table S3), while Dyp-type peroxidases were the fungal counterpart of peroxidases (LiP or MnP) found in the genome (Supplementary Table S3) of the HSTU-AAM51 strain. In particular, glutathione-S-transferase, glutathione reductase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione hydroxylase, glutathione dehydrogenase, S-formyl glutathione hydroxylase, catalase, superoxide dismutase, thioredoxin, peroxiredoxin, glyoxalase, glutaredoxin, alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, thiol peroxidase, and deferrochelatase encoding genes are identified (Supplementary Table S4) and four separate genes that encode formate dehydrogenase were apparent in an operon (Supplementary Table S5).

Plant growth–promoting traits and abiotic stress tolerance

The nitrogen-fixing genes (nifJKEHABMSUNTKV, iscU, and ntrB) added with norR and norV were annotated in the genome of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51. Moreover, ACC deaminase producing vital genes such as dcyD and rimM were found in the genome of the HSTU-AAM51strain. Besides, IAA hormone–producing genes (trpCF, trpS, trpB, trpD) and siderophore-producing genes (fes, entDFS, fhuABCD, tonB, febBG, exbB) existed in the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 genome. Interestingly, genes involved in phosphate metabolism, e.g., pitA, pstABCS, phoABHRU, tomB, and pntAB, and biofilm formation genes such as luxS, efp, and hfq are common in the HSTU-AAM51 strain genome. Moreover, flagellar motility–related genes flgABCGHIJKLM and motAB were predicted in the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 genome (Table 9). The ranges of phosphate uptake, inorganic phosphate transporter, and phosphate starvation genes, e.g., pitA, pstABCU, ugpBE, phoABEHQR, and pntAB, were observed too. Importantly, abiotic stress tolerance genes such as cold shock, heat shock, homeostasis of heavy metals, e.g., arsenic, chromium, and drought resistance genes were annotated in the K. variicola strain HSTU-AAM51 genome (Supplementary Table S5). Interestingly, several kinds of pesticide and herbicide-degrading genes (ampD, glpABQ, pepABD, phnFDGHKLMP, phosphodiesterase), and a number of esterases were annotated in the genome of the strain (Supplementary Table S6).

Table 9.

Genes involved in plant growth–promoting activity

| PGP activities description | Gene name | Locus tag | Product | CDS | E.C. number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen fixation | iscU | GO309_18480 | Fe-S cluster assembly scaffold IscU | 49,393..49779 | - |

| fnifJ | GO309_18025 | Pyruvate:ferredoxin (flavodoxin) oxidoreductase | 122,184..125711 | - | |

| glnK | GO309_04155 | P-II family nitrogen regulator | 198,581..198919 | - | |

| ntrB | GO309_02285 | Nitrate ABC transporter permease | 472,449..473333 | - | |

| nifE | GO309_24775 | Nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein NifE | 38,288..39661 | - | |

| nifH | GO309_24750 | Nitrogenase iron protein | 32,547..33428 | 1.18.6.1 | |

| nifA | GO309_24830 | Nif-specific transcriptional activator NifA | 48,777..50351 | - | |

| nifB | GO309_24835 | Nitrogenase cofactor biosynthesis protein NifB | 50,516..51922 | - | |

| nifM | GO309_24815 | Nitrogen fixation protein NifM | 45,623..46423 | - | |

| nifS | GO309_24795 | Cysteine desulfuraseNifS | 42,563..43765 | 2.8.1.7 | |

| nifU | GO309_24790 | Fe-S cluster assembly protein NifU | 41,708..42547 | - | |

| nifN | GO309_24780 | Nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein NifN | 39,671..41056 | - | |

| nifT | GO309_24765 | Putative nitrogen fixation protein NifT | 36,551..36769 | - | |

| nifK | GO309_24760 | Nitrogenase molybdenum-iron protein subunit beta | 34,949..36511 | 1.18.6.1 | |

| nifV | GO309_24800 | Homocitrate synthase | 43,781..44923 | 2.3.3.14 | |

| Nitrosative stress | norR | GO309_09770 | Nitric oxide reductase transcriptional regulator NorR | 125,015..126571 | - |

| norV | GO309_09775 | Anaerobic nitric oxide reductaseflavorubredoxin | 126,759..128207 | - | |

| Ammonia assimilation | gltB | GO309_14435 | Glutamate synthase large subunit | 231,718..236178 | 1.4.1.13 |

| ACC deaminase | dcyD | GO309_19925 | D-cysteine desulfhydrase | 34,486..35472 | 4.4.1.15 |

| rimM | GO309_09210 | Ribosome maturation factor RimM | 16,698..17246 | - | |

| Siderophore | |||||

| Siderophoreenterobactin | fes | GO309_05185 | Enterochelin esterase | 419,528..420736 | 3.1.1.- |

| entF | GO309_05195 | Enterobactin non-ribosomal peptide synthetaseEntF | 420,978..424859 | 6.3.2.14 | |

| entS | GO309_05215 | Enterobactin transporter EntS | 427,824..429065 | - | |

| fepA | |||||

| entD | GO309_05175 | Enterobactin synthase subunit EntD | 416,344..416973 | 6.3.2.14 | |

| fhuA | GO309_16320 | FerrichromeporinFhuA | 165,154..167361 | - | |

| fhuB | GO309_16335 | Fe(3 +)-hydroxamate ABC transporter permeaseFhuB | 169,094..171076 | - | |

| fhuC | GO309_16325 | Fe3 + -hydroxamate ABC transporter ATP-bindingproteinFhuC | 167,407..168204 | - | |

| fhuD | GO309_16330 | Fe(3 +)-hydroxamate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein FhuD | 168,204..169097 | - | |

| tonB | GO309_02050 | TonB system transport protein TonB | 417,432..418169 | - | |

| fepB | GO309_05220 | Fe2 + -enterobactin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 429,422..430381 | - | |

| fepG | GO309_05205 | Iron-enterobactin ABC transporter permease | 425,715..426704 | - | |

| exbB | GO309_13485 | Tol-pal system-associated acyl-CoA thioesterase | 42,198..42929 | - | |

| Plant hormones | |||||

| IAA production | trpCF | GO309_19275 | Bifunctional indole-3-glycerol-phosphate synthase TrpC/phosphoribosylanthranilateisomeraseTrpF | 56,470..57828 | 4.1.1.48/5.3.1.24 |

| trpS | GO309_07325 | Tryptophan–tRNA ligase | 311,227..312231 | 6.1.1.2 | |

| trpB | GO309_19270 | Tryptophan synthase subunit beta | 55,267..56460 | 4.2.1.20 | |

| trpD | GO309_19280 | Bifunctionalanthranilate synthase glutamate amidotransferase component TrpG/anthranilatephosphoribosyltransferaseTrpD | 57,832..59427 | 2.4.2.18/4.1.3.27 | |

| Phosphate metabolism | pitA | GO309_06800 | Inorganic phosphate transporter PitA | 196,804..198300 | - |

| pstS | GO309_22625 | Phosphate ABC transporter permeasePstA | 54,729..55619 | - | |

| pstC | GO309_22630 | Phosphate ABC transporter permeasePstC | 55,619..56578 | - | |

| pstA | GO309_22625 | Phosphate ABC transporter permeasePstA | 54,729..55619 | - | |

| pstB | GO309_22620 | Phosphate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein PstB | 53,908..54681 | - | |

| phoU | GO309_22615 | Phosphate signaling complex protein PhoU | 53,132..53857 | 3.5.2.6 | |

| ugpB | GO309_07025 | Sn-glycerol-3-phosphate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein UgpB | 241,896..243212 | - | |

| ugpE | GO309_07035 | Sn-glycerol-3-phosphate ABC transporter permeaseUgpE | 244,203..245048 | - | |

| phoA | GO309_03715 | Alkaline phosphatase | 107,973..109388 | 3.1.3.1 | |

| phoE | GO309_03485 | PhosphoporinPhoE | 60,858..61910 | - | |

| phoB | GO309_03780 | Phosphate response regulator transcription factor PhoB | 121,081..121770 | - | |

| phoR | GO309_03785 | Phosphate regulon sensor histidine kinase PhoR | 121,792..123087 | 2.7.13.3 | |

| phoH | GO309_10720 | Phosphate starvation-inducible protein PhoH | 676..1734 | - | |

| pntA | GO309_17575 | Re/Si-specific NAD(P)( +) transhydrogenase subunit alpha | 23,311..24840 | 1.6.1.2 | |

| pntB | GO309_17570 | Re/Si-specific NAD(P)( +) transhydrogenase subunit beta | 21,912..23300 | - | |

| phoQ | GO309_25065 | Two-component system sensor histidine kinase PhoQ | 35,712..37178 | 2.7.13.3 | |

| Biofilm formation | tomB | GO309_04305 | Hha toxicity modulator TomB | 224,892..225266 | - |

| luxS | GO309_09640 | S-ribosylhomocysteinelyase | 104,383..104898 | 4.4.1.21 | |

| efp | GO309_14975 | Elongation factor P | 101,008..101574 | - | |

| hfq | GO309_15100 | RNA chaperone Hfq | 124,744..125052 | - | |

| Sulfur assimilation | cysZ | GO309_18970 | Sulfate transporter CysZ | 156,243..157004 | - |

| cysK | GO309_18965 | Cysteine synthase A | 155,095..156066 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysM | GO309_18925 | Cysteine synthase CysM | 148,124..149035 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysA | GO309_18920 | Sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein CysA | 146,911..148005 | - | |

| cysW | GO309_18915 | Sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter permeaseCysW | 146,046..146921 | - | |

| cysC | GO309_10115 | Adenylyl-sulfate kinase | 194,395..195000 | 2.7.1.25 | |

| cysN | GO309_10120 | Sulfateadenylyltransferase subunit CysN | 195,000..196427 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysD | GO309_10125 | Sulfateadenylyltransferase subunit CysD | 196,437..197345 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysH | GO309_10140 | Phosphoadenosinephosphosulfatereductase | 200,127..200861 | 1.8.4.8 | |

| cysI | GO309_10145 | Assimilatory sulfitereductase (NADPH) hemoproteinsubunit | 200,960..202672 | 1.8.1.2 | |

| cysJ | GO309_10150 | NADPH-dependent assimilatory sulfitereductaseflavoprotein subunit | 202,672..204471 | 1.8.1.2 | |

| cysT | GO309_18910 | Sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter permeaseCysT | 145,213..146046 | - | |

| Sulfur metabolism | cysC | GO309_10115 | Adenylyl-sulfate kinase | 194,395..195000 | 2.7.1.25 |

| cysN | GO309_10120 | Sulfateadenylyltransferase subunit CysN | 195,000..196427 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysD | GO309_10125 | Sulfateadenylyltransferase subunit CysD | 196,437..197345 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysH | GO309_10140 | Phosphoadenosinephosphosulfatereductase | 200,127..200861 | 1.8.4.8 | |

| cysI | GO309_10145 | Assimilatory sulfitereductase (NADPH) hemoprotein subunit | 200,960..202672 | 1.8.1.2 | |

| cysJ | GO309_10150 | NADPH-dependent assimilatory sulfitereductaseflavoprotein subunit | 202,672..204471 | 1.8.1.2 | |

| cysE | GO309_06280 | Serine O-acetyltransferase | 70,686..71507 | 2.3.1.30 | |

| cysQ | GO309_15285 | 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidaseCysQ | 158,377..159120 | 3.1.3.7 | |

| cysK | GO309_18965 | Cysteine synthase A | 155,095..156066 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysS | GO309_04505 | Cysteine–tRNA ligase | 269,952..271337 | 6.1.1.16 | |

| cysZ | GO309_18970 | Sulfate transporter CysZ | 156,243..157004 | - | |

| cysM | GO309_18925 | Cysteine synthase CysM | 148,124..149035 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysA | GO309_18920 | Sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein CysA | 146,911..148005 | - | |

| cysW | GO309_18915 | Sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter permeaseCysW | 146,046..146921 | - | |

| fdxH | GO309_21120 | Formate dehydrogenase subunit beta | 24,484..25386 | - | |

| Antimicrobial peptide | pagP | GO309_05455 | Lipid IV(A) palmitoyltransferasePagP | 482,608..483177 | 2.3.1.251 |

| sapB | GO309_19460 | Peptide ABC transporter permeaseSapB | 95,370..96335 | - | |

| Synthesis of resistance inducers | |||||

| 2,3-butanediol | ilvB | GO309_22405 | Acetolactate synthase large subunit | 9103..10791 | - |

| 2,3-butanediol | ilvA | GO309_23220 | Threonine ammonia-lyase, biosynthetic | 8479..10023 | 4.3.1.19 |

| ilvC | GO309_23230 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 11,065..12540 | 1.1.1.86 | |

| ilvY | GO309_23225 | HTH-type transcriptional activator IlvY | 10,020..10910 | - | |

| ilvD | GO309_23215 | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | 6626..8476 | - | |

| ilvM | GO309_23205 | Acetolactate synthase 2 small subunit | 5359..5616 | 2.2.1.6 | |

| Methanethiol isoprene | metH | GO309_23130 | Methionine synthase | 75,514..79197 | 2.1.1.13 |

| gcpE/ispG | GO309_18555 | Flavodoxin-dependent (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase | 68,399..69520 | 1.17.7.1 | |

| ispE | GO309_02360 | 4-(cytidine 5′-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase | 485,846..486697 | 2.7.1.148 | |

| Hydrolase | ribA | GO309_19355 | GTP cyclohydrolase II | 76,756..77358 | 3.5.4.25 |

| folE | GO309_13000 | GTP cyclohydrolase I FolE | 226,451..227119 | 3.5.4.16 | |

| bglF | GO309_13080 | PTS beta-glucoside transporter subunit IIABC | 242,386..244248 | - | |

| bglX | GO309_13125 | Beta-glucosidaseBglX | 253,401..255698 | .2.1.21 | |

| malZ | GO309_03805 | Maltodextrin glucosidase | 126,431..128248 | 3.2.1.20 | |

| amyA | GO309_19935 | Alpha-amylase | 36,569..38056 | 3.2.1.1 | |

| Symbiosis-related | gcvT | GO309_20480 | Glycine cleavage system aminomethyltransferaseGcvT | 16,096..17190 | 2.1.2.10 |

| phnC | GO309_03520 | Phosphonate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 67,851..68693 | - | |

| tatA | GO309_23525 | Sec-independent protein translocase subunit TatA | 73,386..73637 | - | |

| pyrC | GO309_23855 | Dihydroorotase | 54,965..56011 | 3.5.2.3 | |

| zur | GO309_22965 | Zinc uptake transcriptional repressor Zur | 42,733..43248 | - | |

| Root colonization | |||||

| Chemotaxis | malE | GO309_23020 | Maltose/maltodextrin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein MalE | 54,343..55533 | - |

| rbsB | GO309_22750 | Ribose ABC transporter substrate-binding protein RbsB | 82,965..83855 | - | |

| Adhesive structure | hofC | GO309_16020 | Protein transport protein HofC | 97,395..98600 | - |

| Adhesin production | pgaA | GO309_14720 | Poly-beta-1,6 N-acetyl-D-glucosamine export porinPgaA | 47,429..49897 | - |

| pgaB | GO309_14715 | Poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine N-deacetylasePgaB | 45,405..47420 | 3.5.1.- | |

| pgaC | GO309_14710 | Poly-beta-1,6 N-acetyl-D-glucosamine synthase | 44,084..45412 | - | |

| pgaD | GO309_14705 | Poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine biosynthesis protein PgaD | 43,635..44084 | - | |

| Flagellar protein | murJ | GO309_23825 | Murein biosynthesis integral membrane protein MurJ | 48,906..50441 | - |

| Superoxide dismutase | sodA | GO309_21265 | Superoxide dismutase [Mn] | 54,764..55384 | 1.15.1.1 |

| sodB | GO309_00910 | Superoxide dismutase [Fe] | 184,360..184941 | 1.15.1.1 | |

| sodC | GO309_00860 | Superoxide dismutase [Cu–Zn] SodC2 | 176,890..177411 | 1.15.1.1 | |

| Trehalose metabolism | treB | GO309_15495 | PTS trehalose transporter subunit IIBC | 203,366..204784 | 2.7.1.201 |

| treC | GO309_15490 | Alpha,alpha-phosphotrehalase | 201,659..203314 | 3.2.1.93 | |

| treR | GO309_15500 | HTH-type transcriptional regulator TreR | 204,915..205862 | - | |

| otsA | GO309_03140 | Alpha,alpha-trehalose-phosphate synthase | 646,115..647539 | 2.4.1.15 | |

| otsB | GO309_03145 | Trehalose-phosphatase | 647,514..648302 | 3.1.3.12 | |

| lamB | GO309_23010 | MaltoporinLamB | 51,489..52778 | - |

Discussion

A few Klebsiella spp. are known for the production of lignocellulose-degrading enzymes from different lignocellulose materials [6, 20, 30]. In this study, we demonstrated a new pectinolytic bacteria namely Klebsiella variicola strain HSTU-AAM51. The biochemical tests of the strain were conducted and found that the pectin hydrolytic strains were varied among each other. In fact, they are different from the strains that showed inverse results in MR and VP, respectively [2]. Importantly, Pec-24/HSTU-AAM51 strain’s diazinon mineralization capability concluded that the strain is related to insecticide or toxic chemical degradation role in goat omasum strains. The assembly of extracellular cellulase, xylanase, and pectinase is required to degrade straw and grass materials in the omasum of goats [31]. These results suggested that strain HSTU-AAM51 may be reasoned with potential lignocellulose degradation. Therefore, we selected the HSTU-AAM51 strain for genomic analysis to reveal its lignocellulolytic potentialities.

The quality of the genome sequence was predicted according to GC% of strains DNA [32]. It is accepted that the optimum GC% should be around 40–70% that is covered by the HSTU-AAM51 strain. Therefore, it was ensured that the sequence quality was good for further processing of sequence assembly. MLST analysis, housekeeping genes alignment, phylogenetic tree of whole-genome sequences, digital DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH), ANIb values confirmed that the strain has an intimate intragenus relationship with K. variicola species. Only the environmental strain K. variicola P1CD1 with ligninolytic genetic repertoire is closer (93.3%) according to DDH analysis. But all types of gene and genome alignments lead us to conclude that the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain is much far away from K. pneumonia, etc. The GC content of strain HSTU-AAM51 with three nearest K. variicola strains, namely 13,450 (NZ_CP026013.1), WCHKP19 (NZ_CP020847.1), P1CD1 (CP033631), had shown total CDS 5274, 6066, 5454 gene coding 5163, 5809, 5313, and RNA 124, 128, 118, respectively. However, the strain K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 had shown total CDS 5212, gene coding 5150, and RNA 102 which is markedly deviated from that nearest K. variicola strain sourced from sick humans [33]. The presence of CDS in downstream and upstream was meaningful according to relevant studies. The GC skew is observed in local genomic regions primarily introduced by RNA synthesis, but the analysis of GC skew was first utilized for the computational prediction of ori and ter positions by examining available genome sequences [34].

The bacterial pangenome analysis revealed a framework to answer the genomic diversity within a species. More specifically, bacterial pangenome analysis can reveal individual strain’s single-nucleotide polymorphisms, insertion/deletion variants. and structural variants, at the level of absence or presence of whole genes, annotated functions, and mobile genetic elements such as integrons or prophages [35]. The pangenome graph clearly showed that some part of the genome sequence of HSTU-AAM51 was unmatched compared to the six other strains studied (Fig. 3). Especially, the potential pathogenic genes did not appear in the pangenome analysis. Therefore, it is suggested that the HSTU-AAM51 strain genome has an evolutionary character with no potential pathogenic inducers genes. Besides, the locally collinear blocks (LCB) of the genomes of four nearest strains, namely Klebsiella sp. P1CD1 (CP033631.1), K. variicola 13,450 (CP030173.1), K. variicola FDA ARGOS (CP044050.1) with K. variicola strain HSTU-AAM51, were inspected using Progressive Mauve. The addition, deletion, reshuffling or rearrangements, and inverted of sort of K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 genome sequences were found in various LCBs compared to the LCBs of other nearest strains (CP033631.1, CP030173.1, CP044050.1) genome. Therefore, it is suggested that the K. variicola HSTU-AAM51 strain might be a new member of the K. variicola species and it is a newly evolved strain in Bangladesh.