Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is associated with substantial symptom burden, variability in clinical outcomes, and high direct costs. We sought to determine if a care coordination-based strategy was effective at improving patient symptom burden and reducing healthcare costs for patients with IBD in the top quintile of predicted healthcare utilization and costs.

METHODS:

We performed a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a patient-tailored multicomponent care coordination intervention composed of proactive symptom monitoring and care coordinator-triggered algorithms. Enrolled patients with IBD were randomized to usual care or to our care coordination intervention over a 9-month period (04/2019 – 1/2020). Primary outcomes included change in patient symptom scores throughout the intervention and IBD-related charges at 12 months.

RESULTS:

Eligible IBD patients in the top quintile for predicted healthcare utilization and expenditures were identified. 205 patients were enrolled and randomized to our intervention (n=100) or usual care (n=105). Patients in the care coordinator arm demonstrated an improvement in symptoms scores compared to usual care (coefficient −0.68, 95% CI, −1.18 to −0.18; p=.008) without a significant difference in median annual IBD-related healthcare charges ($10,094 vs $9,080, P=.322).

CONCLUSION:

In this first randomized controlled trial of a patient-tailored care coordination intervention, composed of proactive symptom monitoring and care coordinator-triggered algorithms, we observed an improvement in patient symptom scores but not healthcare charges. Care coordination programs may represent an effective value-based approach to improving symptoms scores without added direct costs in a subgroup of high-risk patients with IBD.

Trial Registration Number:

Keywords: IBD, Quality of Life, Care Coordination, Costs

SHORT SUMMARY:

BACKGROUND

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is associated with substantial symptom burden and high direct costs. Interestingly, less than 10% of patients with IBD patients account for over 50% of healthcare expenditures

FINDINGS

A multicomponent intervention incorporating proactive symptom monitoring and care coordinator-triggered algorithms is feasible for patients with IBD at high risk for health utilization. Our intervention was effective at reducing patient symptoms scores but not healthcare charges.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE

IBD centers can utilize integrated patient portal resources or low-cost web-platforms to support care coordination through symptom monitoring and care coordinator triggered algorithms to reduce symptom burden without increasing costs for high-risk patients with IBD

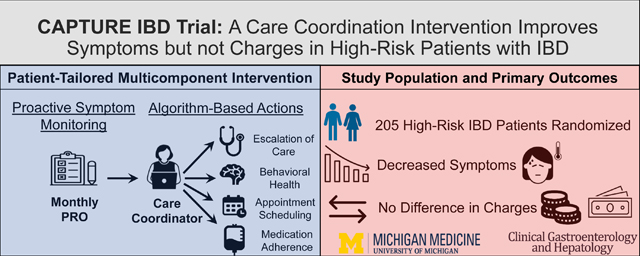

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder characterized by disabling bowel symptoms and progressive bowel damage that has been associated with significant symptom burden, morbidity, and direct healthcare costs.1 It is estimated that less than 10% of the IBD population is responsible for half of all IBD expenditures.2 Several promising interventions, including the texted-based remote monitoring (TELE-IBD) and IBD specialty medical home model, have demonstrated reductions in symptom scores and unplanned emergency service utilization.3–5 However, few of these interventions have been evaluated in a randomized control trial, and overall clinical impact of these prior interventions has been limited.

One major limitation to widespread implementation of existing interventions designed to improve IBD care and healthcare utilization is that it many require substantial organizational resources, or system-wide re-engineering. We aimed to leverage existing patient portal and established treatment algorithms to better coordinate care for these high-risk patients. Our objective was to examine the efficacy of a low-cost patient-tailored care coordination intervention incorporating elements of proactive symptom monitoring and care coordinator-triggered algorithms in improving IBD symptom burden, and reducing health utilization and costs, using a randomized controlled trial design.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The CAPTURE IBD (Clinical coordination And Intense Proactive symptom monitoring To improve Utilization of Resources and reduce Expenditures in high risk IBD patients) study is an investigator-initiated, single-center, randomized controlled trial that took place at a large academic medical center from April 2019 to January 2020 (NCT04796571). An established and previously validated predictive model was applied to all patients with IBD seen in the preceding year (January 2018 to January 2019) to identify patients at high risk for resource utilization and expenditures. This established predictive model utilizes readily available variables in the electronic medical record (EMR) including presence of a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, use of corticosteroids, use of narcotics, anemia, and the frequency of prior IBD-related hospitalizations in the year prior to study initiation. Medication usage was recorded as “used” or “not used” during this period. This model has been shown to identify IBD patients at high risk for hospitalization, emergency department visits, and high treatment charges with high receiver operating characteristic curves.6

Study Population:

Patients 18 to 90 years of age, who had an established diagnosis of IBD, were seen in GI clinic within 1 year of enrollment and were “high-risk” were eligible for enrollment. For purposes of this study, “high-risk” patients were defined as those in the top quintile of predicted risk for subsequent healthcare utilization and costs according to the prediction model described above. Patients with a non-IBD driver for high utilization were excluded from participation (Supplemental Material). No patient was excluded based on their indication for a medication. Eligible patients, who were willing to participate, provided written informed consent using an approved IRB form.

Study Design:

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to a care coordination intervention or usual care. Patients underwent stratified permutated block randomization according to the average predicted risk of IBD-related hospitalization. IBD-related ED visits, and high-treatment costs according to the previously described predicted model.6 A permuted block technique randomizes patients between groups within blocks. Treatment assignments within blocks are determined so that they are random in order but that the desired allocation proportions are achieved exactly within each block. Randomization is then performed separately within each stratum. This approach is an efficient allocation of patients that maximizing statistical power and minimizes type I error.7 Patient assignments were completed in advance and kept in individual, sealed, opaque, sequentially labeled envelopes that were opened at the time of the randomization by the study manager. The study was initiated in January 2019 and enrollment was completed March 2019. Investigators were blinded to the randomization order, but patients, staff, and providers were not blinded to arm assignment. The investigators who validated the data and performed the data analysis remained blinded to patient group assignment.

Care Coordination Intervention:

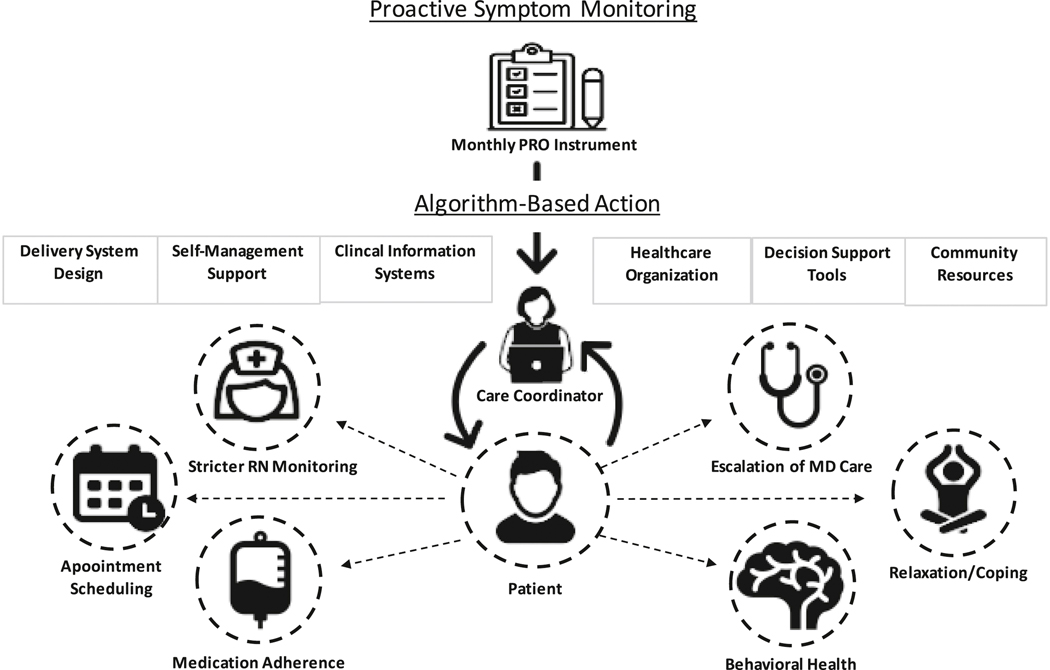

The patient-tailored care coordination intervention included two components, proactive symptom monitoring and care coordinator-enabled triggered algorithms. Patients randomized to the intervention arm were assigned an IBD-focused care coordinator who facilitated use of a symptom-based monitoring algorithm, and supported patient navigation to complement usual care. Our intervention was informed by the Chronic Care Model which identifies six essential elements of a health care system that encourage a productive relationship between care teams and informed, activated patients to improve the quality of chronic illness care.8 Symptom monitoring was facilitated by validated patient report outcome (PRO) measures developed for patients with IBD that address bowel symptoms, functional symptoms, systemic symptoms, daily coping, weekly life impact, and weekly emotional impact.9, 10 PROs highlight patients’ experience with a disease and its treatment, including thoughts, impressions, perceptions, and attitudes. Symptom scores were reviewed by the care coordinator with threshold scores and out of range scores triggering tailored algorithms according to the specific symptom domain of concern (see Outcomes Section and Supplemental Table 1–2). The specific patient-tailored algorithms are detailed in Supplemental Figure 1–3 and were composed of making tailored recommendations according to the specific needs of each individual patient. These patient-tailored actions included making recommendations to the IBD nursing team and physician for stricter monitoring of disease activity (with specific recommendations to obtain a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, C-reactive protein, gastrointestinal panel, and fecal calprotectin), behavioral and medication adherence counseling, facilitation of expedited follow-up with treating providers, and referrals to social work, mental health, and gastroenterology-specific behavioral health services (Figure 1). Threshold scores were determined in a collaborative process and agreed upon by members in our IBD group. Out-of-range scores were determined by comparing a patient’s baseline symptom scores to current scores, and in some cases discussing the results with a patient’s IBD provider, to determine if the observed deviation from baseline represented a meaningful clinical change. The care coordinator was also available at any time throughout the work week for unscheduled patient-initiated contact.

Figure 1:

Overview of Study Protocol

The care coordinator was a certified health educator with a master’s degree in health education and had prior experience as a patient navigator. The care coordinator underwent practical training by the investigators consisting of 80 hours of disease-specific and work-flow education. Work process training included review of existing institutional care pathways including protocols for management of IBD flares, dehydration, changes to mental health, and coping. Proficiency and comfort with materials were evaluated through simulated patient encounters and through direct observation with enrolled patients with feedback and adjustments provided accordingly. Fidelity was assessed periodically by direct observation of the care coordinator with refresher training provided accordingly. The care coordinator also received focused training from a gastrointestinal behavioral health expert.

Control arm:

Patients assigned to the control arm received usual care at the discretion of their gastroenterologist. The control arm completed monthly PRO measures to facilitate symptom score comparisons between the intervention and control arms. While symptom scores were available to the primary gastroenterologist through the medical record, they were not actively reviewed, and patients were not included in PRO triggered treatment algorithms.

Outcomes:

The two primary outcomes were change in total symptom scores, as measured by validated PRO measures, and IBD-related healthcare charges at 12 months of follow-up. Secondary outcomes included emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and medication (corticosteroid, narcotic, biologic, and immunomodulator) utilization at 12 months. A post-hoc assessment of actions taken by the care coordinator and adherence of the patient and the IBD care team to these actions were extracted to assess the degree to which our intervention was implemented as intended. PRO questionnaires were completed monthly by patients in both the usual care and intervention arms. The validated Crohn’s disease (CD)-PRO and ulcerative colitis (UC)-PRO measures are derived from the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index and Mayo Score (Supplemental Table 1–2).9, 10 The PRO measures are scored on a 0 to 135 scale, with lower values representing a lower symptom burden. Patients were reminded to complete PRO measures through portal messaging push notifications followed by a phone call to reduce non-response. IBD-related charges included all provider and facility charges, which were collected through the health system’s billing department.

Statistical Analysis:

Demographic and baseline characteristics were reported as means and standard deviations for normally and as medians and interquartile ranges for non-normally distributed continuous variables, or as counts and percentages for categorical variable and were compared using analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis rank sum, and X2 test, respectively. The relationship between the intervention and outcomes of interest were assessed using regression models. Change in PRO scores over time were evaluated with a generalized time-varying linear mixed-effects model. In this two-level model, repeat PRO measures over time were nested within subjects. Assignment to the intervention or control arm was the categorical independent variable. PRO measurements were the time-varying continuous dependent variable. Unique patient identification number was the random effects variable, allowing us to account for correlations in repeated measures by the same participant over time. This time-varying effects model allows us to use each participant’s PRO score at all time points throughout the intervention. Using a linear regression model, we examined the association between IBD-related charges as a continuous dependent variable, and the intervention, as the dichotomous independent variable. The salary of our care coordinator ($40,000 base salary + 30% fringe benefits = $52,000 per year) was factored into the IBD-related charges for our intervention group. In secondary analyses, logistic regression models were used to examine the association between the intervention and ED visits, hospitalization, and medication (corticosteroid, narcotic, biologic, and immunomodulator) utilization. All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Sensitivity Analysis:

To evaluate for the influence of monthly PRO collection on our study outcomes, we compared IBD charges, ED visits, hospitalizations, and medication utilization at 12 months in the usual care arm to a passive control arm consisting of patients who met eligibility criteria but were not enrolled in the intervention or usual care arms.

Sample Size and Power:

Sample size calculations were based on an anticipated 10% attrition over 12 months and on estimates of standard deviation for primary outcome measures from prior quality improvement trials in IBD.5 We anticipated a 20% improvement in primary outcomes due to our intervention. Given these parameters, to achieve a power of 0.80 with a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, a sample size of n=100 in each group was considered sufficient.

RESULTS:

Study Population:

Six hundred and seventy-five high-risk patients with IBD were screened, and 425 of these patients met inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 205 patients were enrolled and randomized to the intervention (n=100) or usual care (n=105). A 12-month intervention period was planned, however the trial ended at 9 months of follow-up due to the departure of the care coordinator as a result of concerns regarding job stability in context of research funding. An acceptable attrition rate of 11 (10%) participants in the usual care and 8 (8%) participants in the care coordinator arm was noted (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Consort Diagram

The mean age of participants was 48.35 years in the usual care arm compared to 46.69 years in the care coordinator arm (p=.496). The number of female participants was 61.0% in the usual care arm compared to 71.0% in the care coordinator arm (p=.129). The distribution of CD was 75.2% in the usual care arm compared to 77.0% in the care coordinator arm (p=.767). Participants in the care coordinator arm had a statistically insignificant difference in baseline PRO score (39.5 vs 28.0, p=.079) and baseline IBD-related charges ($31,583 vs $23,042, p=.371) compared to usual care, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics

| Usual Care (N=105) | Care Coordinator (N=100) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.35 (17.76) | 46.69 (17.07) | 0.496 |

| Sex, n () | 0.129 | ||

| Female | 64 (61.0) | 71 (71.0) | |

| Male | 41 (39.0) | 29 (29.0) | |

| IBD Type, n (%) | 0.767 | ||

| CD | 79 (75.2) | 77 (77.0) | |

| UC | 26 (24.8) | 23 (23.0) | |

| Primary Payer (%) | 0.391 | ||

| Commercial | 77 (73.3) | 79 (79.0) | |

| Medicare | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Medicaid | 21 (20.0) | 19 (19.0) | |

| Self-pay | 6 (5.7) | 2 (2.0) | |

| Patient Portal, n (%) | 0.845 | ||

| Active | 98 (93.3) | 94 (94.0) | |

| Inactive | 7 (6.7) | 6 (6.0) | |

| Median Baseline PRO Score (IQR) | 28.0 (17.0 – 48.0) | 39.5 (22.2–59.8) | 0.079 |

| Number of ED visits, (SD) | 0.84 (1.81) | 1.08 (1.87) | 0.348 |

| Number of Hospitalizations (SD) | 0.53 (1.20) | 0.47 (1.14) | 0.699 |

| IBD Charges ($), Median (IQR) | 31,583 (0– 118,130) | 23,042 (0–83,230) | 0.371 |

| Number of Endoscopies, mean (SD) | 0.97 (1.07) | 0.91 (1.06) | 0.681 |

| Number of cross-sectional imaging studies, mean (SD) | 1.20 (1.52) | 1.37 (1.67) | 0.446 |

| Steroids, n (%) | 63 (60.0) | 62 (62.0) | 0.769 |

| Narcotics, n (%) | 84 (80.0) | 82 (82.0) | 0.715 |

| Biologic, n (%) | 33 (31.4) | 28 (28.0) | 0.591 |

| Immunomodulator, n (%) | 39 (37.1) | 42 (42.0) | 0.477 |

| Psychiatric Disorder, n (%) | 46 (43.8) | 47 (47.0) | 0.646 |

| Risk Model: predicted IBD-related* Hospitalization, (SD) | 29.59 (10.72) | 28.43 (10.87) | 0.442 |

| Risk Model: predicted IBD-related ED Visit * , (SD) | 43.82 (14.33) | 43.46 (14.40) | 0.859 |

| Risk Model: predicted High Treatment Costs * , (SD) | 38.70 (10.78) | 38.07 (9.58) | 0.656 |

N/n (number), SD (Standard Deviation); IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease); PRO (Patient Reported Outcome) ED(Emergency Department); IQR(Interquartile range)

Calculated according to the Michigan IBD Risk Model which is a predictive model that utilizes readily available variables in the electronic medical record (EMR) including presence of a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, use of corticosteroids, use of narcotics, anemia, and frequency of prior IBD-related hospitalizations in the year prior to study initiation, and has been shown to identify IBD patients at risk for IBD-related hospitalization, IBD-related emergency department visits, and high treatment charges.6 Medication use indicated use during in the year prior to study initiation and did necessarily indicate dependence or persistent use

Primary Outcomes:

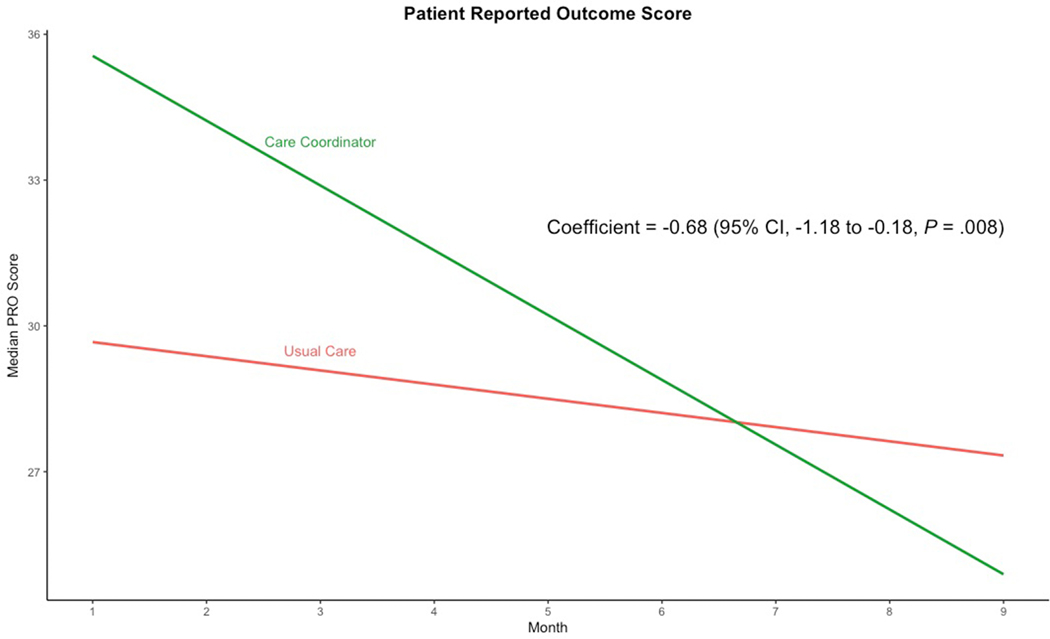

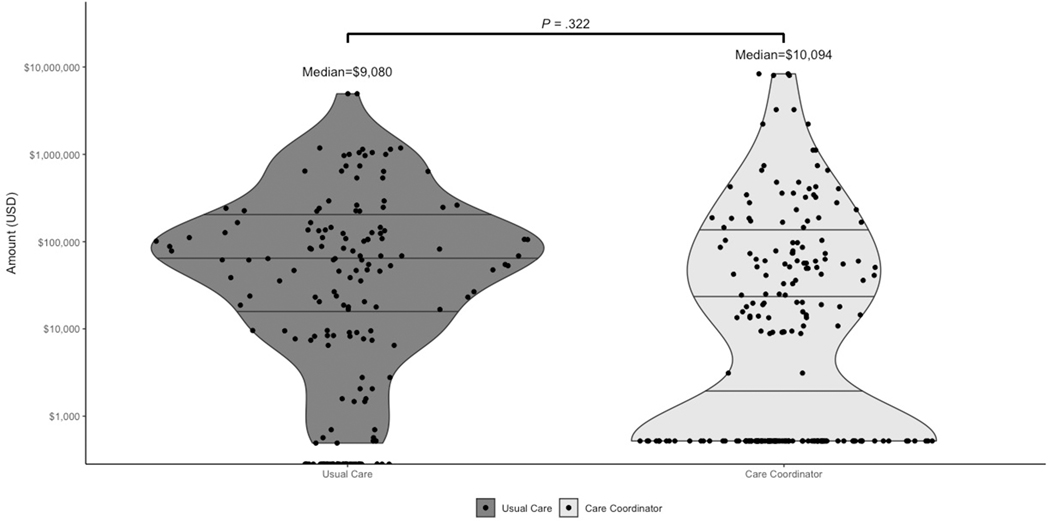

Monthly PRO measures completion rates for each arm can be seen in Supplemental Table 3. Patients in the intervention arm experienced a significant reduction in total PRO scores compared to usual care (regression coefficient −0.68; 95% CI, −1.18 to −0.18; p=.008), after controlling for baseline PRO measures (Figure 3 and Table 2). This implies that patients receiving the care coordinator intervention experienced a 0.68-point improvement in total PRO scores for each month of enrollment compared to patients enrolled in the usual care arm. Therefore, in a 9-month intervention, a patients’ scores on average declined 6.12 points, which represents a 15% improvement from a median baseline PRO score. Supplemental Table 4 provides the change in monthly PRO scores by instrument domain and IBD-type. There was no significant difference in IBD-related charges (regression coefficient 64123.28; 95% CI, −64365.88 to 192612.4; p= .326) in the intervention arm compared to usual care after controlling for baseline IBD-related charges and when factoring the added costs of employing a full-time care coordinator (Figure 4 and Table 2).

Figure 3:

Care Coordination Intervention and Change in Patient Reported Outcome Scores Over Study Period

Table 2:

Regression Output for the Care Coordinator Arm Compared to Usual Care

| Variables | Beta Coefficients | Odds Ratios | Confidence Interval (LCI, UCI)) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in PRO Scores overtime | −0.68 | − | −1.18, −0.18 | 0.008 |

| IBD-Related Charges | 64643.28 | − | −63845.88, 193132.44 | 0.322 |

| Emergency Department | −0.4785 | 0.62 | 0.27, 1.39 | 0.253 |

| Hospitalization | −0.4682 | 0.63 | 0.29, 1.33 | 0.225 |

| Steroids | 0.6004 | 1.82 | 0.87, 3.91 | 0.115 |

| Narcotics | 0.3605 | 1.43 | 0.76, 2.73 | 0.268 |

| Biologics | 0.2974 | 0.74 | 0.38, 1.43 | 0.376 |

| Immunomodulators | −0.07525 | 0.93 | 0.44, 1.96 | 0.843 |

PRO (Patient Reported Outcome); IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease); LCI (lower confidence interval); UCI (upper confidence interval)

Figure 4:

Care Coordination Intervention and IBD-related Charges at 12-months

Secondary Outcomes:

There was no significant difference in the proportion of ED visits [odds ratio (OR) 0.62; 95% CI, 0.27 to 1.39; p= 0.253], hospitalizations (OR 0.63; 95% CI, 0.29 to 1.33, p= .225), corticosteroid (OR 1.82; 95% CI 0.87 to 3.91; p= .115), narcotic (OR 1.43; 95% CI 0.76 to 2.73, p= .268), biologic (OR 0.74; 95% 0.38 to 1.43, p= .376), or immunomodulator (OR 0.93; 95% CI 0.44 to 1.96, p= .843) utilization in the care coordinator arm as compared to the usual care arm (Supplemental Figure 4 and Table 2).

Care Coordination Action and Adherence:

Assessment of actions taken by the care coordinator aspatient and care team adherence to these actions are reported in Supplement Table 5. One hundred and fifty-four care coordinator triggered actions took place in 58 (58%) patients. The remaining 42 (42%) of patients did not receive a care coordinator action either due to not completing their surveys or having stable or in range scores which did not meet criteria to trigger an action.

Sensitivity Analysis:

Baseline characteristics of the passive control arm were similar to the usual care arm, with similar baseline IBD-related charges, ED visits, hospitalizations, and medication utilization. The exception that patients in the passive control arm were younger (44.03 vs 48.45 years, p=.041), and had a lower number of hospitalizations (0.32 vs 0.53, p=.049). Patients in the passive control arm had an insignificantly lower proportions of CD (64.5% vs 75.2%, p =0.053), lower proportions of active patient portal usage (13.2% vs 6.7%, p=.08), and lower baseline IBD-related charges ($14,924 vs $31,583, p=.064) (Supplemental Table 6). Similar trends were observed when comparing the usual care and passive control arms with the exception that patients in the usual care arm were more likely to use biologics, compared to the passive control arm (OR 1.78; 95% CI 1.01 to 3.12; p=.045) (Supplemental Table 7).

DISCUSSION:

Our study demonstrates that a multicomponent patient-tailored care coordination intervention is effective at improving patient symptoms but not IBD-related healthcare charges. To our knowledge, the CAPTURE IBD study represents the first randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a multicomponent care coordination intervention incorporating proactive symptom monitoring and care coordinator-triggered algorithms for patients with IBD at high predicted risk for healthcare utilization and costs. In our secondary analysis, a numeric reduction in healthcare utilization was evident in both the intervention and usual care arms, without a significant difference between groups.

Our results vary from findings noted in a randomized controlled trial of a text-based intervention (TELE-IBD) incorporating symptom monitoring, tailored alerts and action plans. TELE-IBD was not effective in reducing disease activity or improving quality of life, but was found to reduce hospitalization rates compared to usual care.5 In addition, while resource intensive and requiring widespread re-engineering, IBD-based medical home programs such as the University of Pittsburgh model and Illinois Gastroenterology Group’s Project Sonar both incorporate care coordination efforts as a component of their program. These initiatives have led to lower frequencies of ED visits and hospitalizations, and a reduction in symptoms. It is important to note that these programs were not examined in context of a randomized control trial, making it challenging to interpret the specific factors responsible for improvements.3, 4

Improvement in symptom scores suggest that proactive symptom monitoring and care coordination-triggered algorithms may represent an effective patient-tailored intervention without added costs for high-risk patients with IBD. Indeed, it is important to consider that efforts to improve quality of care may come at an increased cost. For example, proactive symptom monitoring have the potential to increase initial healthcare utilization in an effort to improve health outcomes, as was observed in the tight control arm of the CALM trial.11 This could potentially explain the higher proportion of biologic use in the usual care arm compared to the passive control arm in our study. It is important to note that while symptoms scores decreased by 0.68 points per month (6.12 points over the intervention period for a 15% improvement from baseline) in the intervention arm compared to usual care, it is unknown if this represents a meaningful clinical difference as further research is needed to calculate a minimal clinically important difference and to transform the PRO scores into quality-adjusted life years.

IBD-related charges decreased in both the intervention and usual care arms, without a significant intervention effect. This suggests that observed reductions may be secondary to external factors unrelated to participation in a clinical trial, such as improved access to IBD care, improved symptom monitoring after a period of poorly controlled IBD, or simply regression to the mean.12, 13 Of note, factoring in the costs of employing a full-time care coordinator did not result in a significant difference in charges between the two groups.

By assessing for differences in baseline characteristics between passive control and usual care arm, we can assess for potential selection bias among enrolled and non-enrolled subjects. Healthcare charges and utilization in our usual care arm was not statistically different than in our passive control arm. Therefore, this reduction in healthcare charges and utilization is less likely related to intervention contamination related to symptom monitoring by the PRO instrument alone.

The strengths of this study include its randomized design, use of a validated PRO questionnaire to measure our primary outcome, and the development of an intervention grounded in existing structures, such as the patient portal and existing treatment algorithms. Further, we were able to employ validated risk models, and engage patients with IBD to complete routine symptom monitoring questionnaires, with sufficient (59.4% - 63.7%) monthly PRO completion rates.14 CAPTURE IBD, which utilizes a patient navigator in a care coordinator role with patient portal-supported symptom monitoring, is more easily scalable than models of care that require widespread re-engineering. The relatively high adherence to the care coordinator’s actions supports a high implementation fidelity, suggests that our study intervention was delivered as intended, further strengthening our findings. It is important to recognize that imperfect action adherence could be due to patient/provider non-adherence to actions, care coordinator overcalls, physician review deeming an action unnecessary or already having a plan to make changes to a care plan prior to PRO score review.

The study findings need to be interpreted in context of study limitations. It important to recognize that our study was completed at a tertiary care center with reliable and readily available patient portal, and behavioral and psychological support, limiting the generalizability of our approach to smaller practices. Our study period was shortened by the departure of our care coordinator. While this demonstrates the real-world challenges of implementing a care coordinator driven intervention, it has no effect on our power to detect differences between the two arms, however it could have potentially limited the intervention effect, as clinical outcome may require sustained intervention to effect meaningful change. This unanticipated event highlights a drawback to investing efforts in individuals rather than functional roles and will inform future iterations of this intervention. While differences in baseline PRO measures were evident after randomization, we adjusted for these baseline characteristics in our analysis. Outcome data was collected from the study site and cannot account for care received at an outside facility. In addition, this study was not designed to assess for objective responses (e.g., biomarker or endoscopic remission), though these endpoints will be considered in future work. Finally, our intervention is composed of several components, but the study was not designed to examine the efficacy of each individual component. Future studies should examine potential mediators, such as self-efficacy and patient activation, to better understand the mechanistic pathway and unmeasured confounders.

In conclusion, a patient-tailored care coordination intervention composed of proactive symptom monitoring and care coordinator-triggered algorithms is feasible and effective in improving patient symptoms but not charges among a cohort of high-risk patients with IBD at a single tertiary referral center. We are optimistic that a care-coordinator enabled strategy may complement existing models of care to provide care coordination at scale. Larger, multi-center studies are needed to better evaluate the efficacy of this care coordination intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of the Funding Source:

Funding support for this was study was provided by Twine Clinical Consulting LLC. Trial was design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript generation were conducted by the principal academic investigators and completely independent of the funding source.

Grant Support: This study was funded with the support from the Twine Clinical Consulting LLC. (Dr. Higgins). Dr. Berinstein is supported by T32 DK062708. Dr Cohen-Mekelburg is supported by KL2TR002241 through the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Adams is supported by a 2018 American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Grant.

Abbreviations:

- CAPTURE

Clinical coordination And Proactive symptom monitoring To improve Utilization of resources and Reduce Expenditures in high risk IBD patients

- CD

Crohn’s Disease

- IBD

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- UC

Ulcerative Colitis

- U-M

University of Michigan

- EMR

Electronic Medical Records

- SDOH

Social Determinants of Health

- PRO

Patient Reported Outcomes

Footnotes

This trial is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04796571).

Disclosures:

PDRH received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Genentech, JBR Pharma and Lycera. All other authors report no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Mehta F. Report: economic implications of inflammatory bowel disease and its management. Am J Manag Care. Mar 2016;22(3 Suppl):s51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prenzler A, Bokemeyer B, von der Schulenburg JM, Mittendorf T. Health care costs and their predictors of inflammatory bowel diseases in Germany. Eur J Health Econ. Jun 2011;12(3):273–83. doi: 10.1007/s10198-010-0281-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh S, Brill JV, Proudfoot JA, et al. Project Sonar: A Community Practice-based Intensive Medical Home for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 12 2018;16(12):1847–1850.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regueiro M, Click B, Anderson A, et al. Reduced Unplanned Care and Disease Activity and Increased Quality of Life After Patient Enrollment in an Inflammatory Bowel Disease Medical Home. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 11 2018;16(11):1777–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross RK, Langenberg P, Regueiro M, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of TELEmedicine for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (TELE-IBD). Am J Gastroenterol. 03 2019;114(3):472–482. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0272-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limsrivilai J, Stidham RW, Govani SM, Waljee AK, Huang W, Higgins PD. Factors That Predict High Health Care Utilization and Costs for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 03 2017;15(3):385–392.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broglio K. Randomization in Clinical Trials: Permuted Blocks and Stratification. JAMA. Jun 05 2018;319(21):2223–2224. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. Oct 2002;288(14):1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins PDR, Harding G, Leidy NK, et al. Development and validation of the Crohn’s disease patient-reported outcomes signs and symptoms (CD-PRO/SS) diary. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;2(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0044-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins PDR, Harding G, Revicki DA, et al. Development and validation of the Ulcerative Colitis patient-reported outcomes signs and symptoms (UC-pro/SS) diary. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;2(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0049-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panaccione R, Colombel JF, Travis SPL, et al. Tight control for Crohn’s disease with adalimumab-based treatment is cost-effective: an economic assessment of the CALM trial. Gut. 04 2020;69(4):658–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smelt AF, van der Weele GM, Blom JW, Gussekloo J, Assendelft WJ. How usual is usual care in pragmatic intervention studies in primary care? An overview of recent trials. Br J Gen Pract. Jul 2010;60(576):e305–18. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X514819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brixner D, Mittal M, Rubin DT, et al. Participation in an innovative patient support program reduces prescription abandonment for adalimumab-treated patients in a commercial population. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1545–1556. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S215037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louissaint J, Lok AS, Fortune BE, Tapper EB. Acceptance and Use of a Smartphone Application in Cirrhosis. Liver Int. Apr 2020;doi: 10.1111/liv.14494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.