Abstract

Study Objectives:

The association between sleep apnea (SA) and cataract was confirmed in a comprehensive large-scale study. This study aimed to investigate whether SA was associated with increased risk of cataract.

Methods:

The 18-year nationwide retrospective population-based cohort study used data retrieved from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database. We selected adult patients with a diagnosis of SA, based on diagnostic codes (suspected SA cohort) or on presence of diagnosis after polysomnography (SA cohort), and matched each of them to 5 randomly selected, and age- and sex-matched control participants. The incidence rate of cataract was compared between patients with SA and the controls. The effect of SA on incident cataract was assessed using multivariable Poisson regression and Cox regression analyses.

Results:

A total of 6,438 patients in the suspected SA cohort were matched with 32,190 controls (control A cohort), including 3,616 patients in the SA cohort matched with 18,080 controls (control B cohort). After adjusting for age, sex, residency, income level, and comorbidities, the incidence rates of cataract were significantly higher in the SA cohorts than in the corresponding control cohorts. SA was an independent risk factor for incident cataract (adjusted hazard ratio [95% confidence interval]: 1.4 [1.2–1.6]). In patients with SA, elder age, heart disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus were independent risk factors for incident cataract.

Conclusions:

Our study revealed a significantly higher risk for developing cataract in patients with SA. Physicians caring for patients with SA should be aware of this ophthalmic complication.

Citation:

Liu P-K, Chang Y-C, Wang N-K, et al. The association between cataract and sleep apnea: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(3):769–777.

Keywords: sleep apnea, sleep-disordered breathing, cataract, risk factor

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Cataract remains one of the major global causes of visual disabilities nowadays. The association between sleep apnea (SA) and cataract has only been reported in a few previous studies. A comprehensive large-scale study is still needed to further confirm whether SA increases the risk of cataract.

Study Impact: Patients with SA have a significantly higher risk of cataract than control participants. Heart disease, pulmonary disease, and diabetes are risk factors for cataract in patients with SA. Physicians caring for patients with SA should be aware of this reversible ophthalmic complication.

INTRODUCTION

Cataract remains one of the major global causes of visual disabilities currently. It is associated with > 50% of blindness and 33% of patients with visual impairment in the world.1 Despite being a cause of reversible vision loss, many barriers to appropriate cataract surgeries, such as unawareness of the disease, lack of medical resources, surgical quality, and the expense of surgical treatment, still exist, leading to unsatisfactory cataract surgical coverage.2,3 In 2020, up to 15.2 million people worldwide experienced blindness owing to cataract, which remained the leading cause of blindness in those aged 50 years and older.4

Sleep apnea (SA), the most common nocturnal sleep-disordered breathing, can be categorized into central SA and obstructive SA (OSA), and OSA is the predominant type (> 90%).5,6 Patients with SA experience recurrent and involuntary disruption or pause in breathing during sleep. Polysomnography (PSG) is typically used for confirming the diagnosis. SA leads to repetitive episodes of apneic insults, which are commonly followed by transient night-time drop in blood oxygen saturation and accumulation of blood carbon dioxide during sleep.7,8 The repeated hypoxemia-reoxygenation cycles may evoke oxidative stress, systemic inflammatory response, autonomic dysfunction with sympathetic activation, and coagulation-fibrinolysis imbalance. These may induce many systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease and metabolic dysregulation.9,10

Several risk factors for cataract have been reported before, including steroid use, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, alcohol consumption, ultraviolet-B exposure, and lower educational level.3,11,12 SA has been associated with several ocular diseases, including retinal vein occlusion, nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, central serous chorioretinopathy, glaucoma, and floppy eyelid syndrome.13,14 A small cross-sectional case-control study reported a greater risk of cataract in patients with OSA.15 However, the association between SA and cataract has not been investigated in a large-scale study. Therefore, we conducted this population-based cohort study to analyze the association between SA and cataract.

METHODS

Data sources

We performed a nationwide retrospective population-based cohort study using the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) managed by Taiwan National Health Research Institute. Taiwan government commenced the National Health Insurance (NHI) in March 1995, as a compulsory social health insurance program to care for all residents in Taiwan. The majority of hospitals and clinics (> 97%) were under contract to NHI, and > 96% of residents were covered under this program. The Bureau of NHI conducts constant cross-checks and validation of the medical records, thus assuring the accuracy of diagnostic coding in the database. NHIRD comprises all claims from both ambulatory and inpatient care and has contributed data to many epidemiological studies. The NHIRD encrypts the identification information of the patients and hospital identifiers for the sake of privacy; hence, researchers are not able to look for the individuals or health care providers via the database. In the current study, we adopted Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010 (LHID2010) of NHIRD, comprising a cohort of 1 million persons randomly sampled from NHI beneficiaries in 2010 along with their related data through the end of 2013. Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study (KMUH-IRB-EXEMPT-20130034 and KMUHIRB-EXEMPT(II)-20150068) and exempted it from the requirement for written informed consents, because all identifiable personal information had been encrypted in the NHIRD to protect individual privacy. The study was conducted in adherence with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

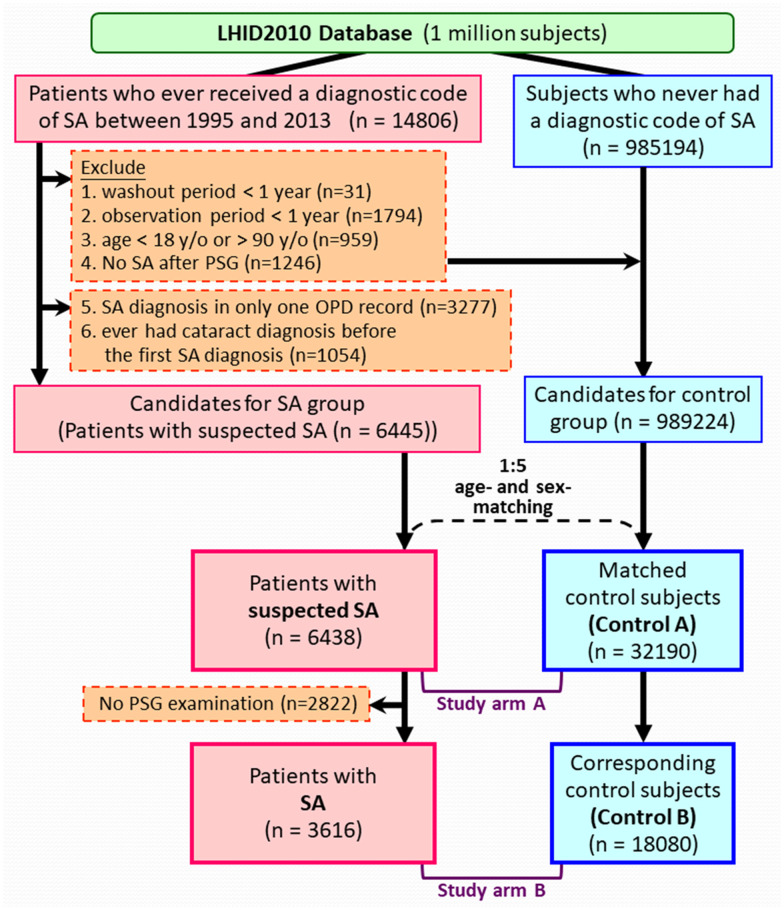

Figure 1 demonstrates the algorithm used to identify the cohorts, which was similar to our previous studies.14,16 Concisely, patients who received a diagnostic code of SA between March 1, 1995, and December 31, 2013, were first identified. The diagnosis of SA consisted of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm, accessed October 26, 2021), codes 780.51, 780.53, and 780.57.16–18 The ICD-9-CM code of 366.xx was used to identify the major events of cataract development.19 All participants were tracked from the index date (the date of participant’s first SA diagnosis) to either their first diagnosis of cataract, end of the study period, or end of the record due to withdrawal from the NHI program or death, whichever occurred first. The exclusion criteria included: follow-up periods (from the index dates to the end of their records) or washout periods (from the NHI enrollment to the index date) of less than 1 year, no SA diagnosis after PSG (in those who had tested with PSG examination), diagnosis with cataract before the index date, or age < 18 or > 90 years old.

Figure 1. Algorithm for identifying the study population.

LHID2010 = Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010, OPD = outpatient department, PSG = polysomnography, SA = sleep apnea.

Through the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified the “suspected SA cohort” primarily based on the diagnostic codes. From this cohort, the patients who still maintained SA diagnosis after a PSG were further extracted as the “SA cohort”.

Each patient with suspected SA was matched to 5 randomly selected controls according to age and sex. The index date of a patient with SA was designated as the index date of matched control participants. During selection of controls, we applied exclusion criteria similar to those for patients with SA to ensure the absence of any previous cataract diagnosis before the index date, as well as sufficient washout and follow-up periods (at least a year). The control A cohort and control B cohort were those matched to the suspected SA cohort and the SA cohort, respectively.

Definitions of variables

The endpoint of this study was the occurrence of cataract, ie, when the first cataract diagnosis was coded. To ensure the reliability of the diagnosis, only those with cataract diagnosis in at least 2 outpatient claims or 1 inpatient claim were accepted as having cataract. The presence of comorbidity was recognized by the presence of any corresponding diagnostic ICD-9-CM codes in at least 2 outpatient claims or 1 inpatient claim, with the initial record of the diagnosis before the index date. The Charlson Comorbidity Index score was then computed according to the comorbidities.14,16,20

Statistical analysis

To validate and solidify the study result, we created and investigated 2 study arms. Study arm A consisted of comparison between the suspected SA cohort and control A cohort, and study arm B compared the SA cohort with control B cohort.

Pearson χ2 test was applied for analyzing categorical variables, and Student’s t test was used for continuous variables. The incidence rate of cataract was calculated as the number of incident cataract during the follow-up period divided by the total person-years. Incidence rate ratio represented the ratio of the cataract incidence rates in SA cohort and the corresponding control cohort. A 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated for incidence rate ratio, as the observed numbers of cataract were postulated to follow a Poisson probability distribution. Stratified analyses were performed according to sex, age group, the presence of any comorbidity, income level, or residency. Adjusted incidence rate ratios were calculated with adjustment for sex, age, residency, income level, and the presence of various comorbidities (except for the variable used for stratification). Multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed to determine the effect of SA on incident cataract, and the results were presented as hazard ratios with 95% CIs. Multivariable Cox regression analyses were also applied to determine risk factors for cataract in patients with SA. In addition to the maximal model, we also built reduced models by a backward-variable selection method, eliminating variables with a P value > .05. All statistical analyses were completed with the SAS system (version 9.4 for Windows; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), including extraction, computation, linkage, processing, and sampling of data. A 2-sided P value of < .05 was adopted as the criterion for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Figure 1 illustrates the algorithm for identifying study cohorts (suspected SA, n = 6,438; SA, n = 3,616) and age- and sex-matched control cohorts (control A, n = 32,190; control B, n = 18,080). The mean (± standard deviation) ages were 44.2 (±12.3) and 44.7 (±11.5) years in study arm A (suspected SA and control A cohorts) and study arm B (SA and control B cohorts), respectively (Table 1). Compared with the corresponding control participants, patients with SA (in both suspected SA and SA cohorts) had significantly higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score and more comorbidities, including heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, major neurological disorder, chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, and cancer.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Study Arm A | Study Arm B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected SA | Control A | P | SA | Control B | P | |

| n | 6,438 | 32,190 | 3,616 | 18,080 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 2,001 (31) | 10,005 (31) | 718 (20) | 3,590 (20) | ||

| Male | 4,437 (69) | 22,185 (69) | 2,898 (80) | 14,490 (80) | ||

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 44.2 ± 12.3 | 44.2 ± 12.3 | 44.7 ± 11.5 | 44.7 ± 11.5 | ||

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| ≤ 40 y | 2,539 (39) | 12,695 (39) | 1,341 (37) | 6,705 (37) | ||

| 40 < age ≤ 50 y | 1,861 (29) | 9,305 (29) | 1,105 (31) | 5,525 (31) | ||

| > 50 y | 2,038 (32) | 10,190 (32) | 1,170 (32) | 5,850 (32) | ||

| Residency | < .0001 | < .0001 | ||||

| Northern Taiwan | 3,555 (55) | 16,425 (51) | 2,120 (59) | 9,140 (51) | ||

| Other areas | 2,883 (45) | 15,765 (49) | 1,496 (41) | 8,940 (49) | ||

| Monthly income (NT$), median (IQR) | 24,000 (1,249–43,900) | 21,900 (1,249–40,100) | < .0001 | 30,300 (17,280–48,200) | 21,900 (1,249–42,000) | < .0001 |

| Monthly income (NT$), n (%) | < .0001 | < .0001 | ||||

| ≤ 24,000 | 3,322 (52) | 18,780 (58) | 1,628 (45) | 10,139 (56) | ||

| > 24,000 | 3,116 (48) | 13,410 (42) | 1,988 (55) | 7,941 (44) | ||

| CCI score, mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | < .0001 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | < .0001 |

| CCI score, n (%) | < .0001 | < .0001 | ||||

| = 0 | 2,331 (36) | 18,666 (58) | 1,224 (34) | 10,268 (57) | ||

| = 1 | 1,728 (27) | 7,299 (23) | 976 (27) | 4,224 (23) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 2,379 (37) | 6,225 (19) | 1,416 (39) | 3,588 (20) | ||

| Underlying diseases, n (%) | ||||||

| Heart disease | 245 (4) | 502 (2) | < .0001 | 157 (4) | 294 (2) | < .0001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 59 (1) | 173 (1) | .0003 | 43 (1) | 105 (1) | < .0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 199 (3) | 362 (1) | < .0001 | 124 (3) | 208 (1) | < .0001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 93 (1) | 215 (1) | < .0001 | 58 (2) | 113 (1) | < .0001 |

| Major neurological disorder | 563 (9) | 1,265 (4) | < .0001 | 343 (9) | 688 (4) | < .0001 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 537 (8) | 1,169 (4) | < .0001 | 331 (9) | 633 (4) | < .0001 |

| Dementia | 33 (1) | 94 (0) | .0048 | 19 (1) | 49 (0) | .0125 |

| Hemiplegia | 55 (1) | 152 (0) | .0001 | 33 (1) | 96 (1) | .0064 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1,906 (30) | 5,100 (16) | < .0001 | 1,123 (31) | 2,869 (16) | < .0001 |

| Connective tissue disease | 187 (3) | 471 (1) | < .0001 | 94 (3) | 239 (1) | < .0001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 2,085 (32) | 6,082 (19) | < .0001 | 1,192 (33) | 3,534 (20) | < .0001 |

| Liver disease | 1,631 (25) | 4,694 (15) | < .0001 | 1,039 (29) | 2,872 (16) | < .0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 720 (11) | 2,268 (7) | < .0001 | 444 (12) | 1,326 (7) | < .0001 |

| Renal disease | 256 (4) | 681 (2) | < .0001 | 152 (4) | 372 (2) | < .0001 |

| Cancer | 327 (5) | 875 (3) | < .0001 | 179 (5) | 482 (3) | < .0001 |

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index, IQR = interquartile range, NT$= New Taiwan Dollar, SA = sleep apnea, SD = standard deviation.

Compared with the corresponding control participants, patients with SA had significantly higher incidence rate of cataract (adjusted incidence rate ratio [95% CI]: 1.4 [1.4–1.5] and 1.4 [1.3–1.5] in study arms A and B, respectively) (Table 2). Stratified analyses showed significantly higher incidence rates of cataract in patients with SA than in their corresponding control participants in all strata.

Table 2.

Incidence rate of cataract after the index date in each group.

| Study Arm A | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected SA | Control A | Crude IRR [95% CI] | Adjusted IRR [95% CI] | |||||||

| n | Cata | PY | IR | n | Cata | PY | IR | |||

| Whole study population | 6,438 | 626 | 37,243.8 | 16.8 | 32,190 | 2,052 | 191,226.4 | 10.7 | 1.6 [1.5–1.7]*** | 1.4 [1.4–1.5]*** |

| Stratified analyses | ||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 2,001 | 252 | 11,349.2 | 22.2 | 10,005 | 809 | 58,584.9 | 13.8 | 1.6 [1.4–1.8]*** | 1.4 [1.3–1.6]*** |

| Male | 4,437 | 374 | 25,894.6 | 14.4 | 22,185 | 1,243 | 132,641.5 | 9.4 | 1.5 [1.4–1.7]*** | 1.5 [1.4–1.6]*** |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 4,400 | 125 | 27,442.2 | 4.6 | 22,000 | 382 | 138,125.7 | 2.8 | 1.6 [1.5–1.8]*** | 1.3 [1.2–1.4]*** |

| > 50 | 2,038 | 501 | 9,801.5 | 51.1 | 10,190 | 1,670 | 53,100.7 | 31.4 | 1.6 [1.5–1.8]*** | 1.5 [1.3–1.6]*** |

| Residents in | ||||||||||

| Northern Taiwan | 3,555 | 342 | 20,697.9 | 16.5 | 16,425 | 979 | 97,571.3 | 10.0 | 1.6 [1.5–1.8]*** | 1.5 [1.4–1.6]*** |

| Other areas | 2,883 | 284 | 16,545.9 | 17.2 | 15,765 | 1,073 | 93,655.1 | 11.5 | 1.5 [1.4–1.6]*** | 1.4 [1.3–1.6]*** |

| Monthly income | ||||||||||

| ≤ NT$24,000 | 3,322 | 375 | 18,784.8 | 20.0 | 18,780 | 1,407 | 111,292.7 | 12.6 | 1.6 [1.5–1.7]*** | 1.4 [1.3–1.5]*** |

| > NT$24,000 | 3,116 | 251 | 18,459.0 | 13.6 | 13,410 | 645 | 79,933.7 | 8.1 | 1.7 [1.5–1.8]*** | 1.5 [1.4–1.7]*** |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||||

| No (CCI score = 0) | 2,331 | 139 | 15,527.2 | 9.0 | 18,666 | 752 | 120,479.8 | 6.2 | 1.4 [1.3–1.6]*** | 1.8 [1.6–1.9]*** |

| Yes (CCI score ≥ 1) | 4,107 | 487 | 21,716.6 | 22.4 | 13,524 | 1,300 | 70,746.7 | 18.4 | 1.2 [1.1–1.3]*** | 1.3 [1.2–1.5]*** |

| Study Arm B | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | Control B | Crude IRR [95% CI] | Adjusted IRR [95% CI] | |||||||

| n | Cata | PY | IR | n | Cata | PY | IR | |||

| Whole study population | 3,616 | 319 | 19,695.7 | 16.2 | 18,080 | 1,041 | 101,318.7 | 10.3 | 1.6 [1.5–1.7]*** | 1.4 [1.3–1.5]*** |

| Stratified analyses | ||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 718 | 82 | 3,638.1 | 22.5 | 3,590 | 282 | 18,838.6 | 15.0 | 1.5 [1.3–1.8]*** | 1.3 [1.1–1.5]** |

| Male | 2,898 | 237 | 16,057.6 | 14.8 | 14,490 | 759 | 82,480.1 | 9.2 | 1.6 [1.5–1.8]*** | 1.5 [1.3–1.6]*** |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 2,446 | 66 | 14,185.0 | 4.7 | 12,230 | 192 | 71,482.4 | 2.7 | 1.7 [1.6–1.9]*** | 1.4 [1.2–1.5]*** |

| > 50 | 1,170 | 253 | 5,510.7 | 45.9 | 5,850 | 849 | 29,836.3 | 28.5 | 1.6 [1.4–1.8]*** | 1.4 [1.2–1.6]*** |

| Residents in | ||||||||||

| Northern Taiwan | 2,120 | 187 | 12,123.6 | 15.4 | 9,140 | 502 | 51,608.3 | 9.7 | 1.6 [1.4–1.8]*** | 1.4 [1.3–1.6]*** |

| Other areas | 1,496 | 132 | 7,572.1 | 17.4 | 8,940 | 539 | 49,710.3 | 10.8 | 1.6 [1.4–1.8]*** | 1.4 [1.3–1.6]*** |

| Monthly income | ||||||||||

| ≤ NT$24,000 | 1,628 | 171 | 8,408.4 | 20.3 | 10,139 | 661 | 56,388.5 | 11.7 | 1.7 [1.5–1.9]*** | 1.5 [1.3–1.6]*** |

| > NT$24,000 | 1,988 | 148 | 11,287.3 | 13.1 | 7,941 | 380 | 44,930.1 | 8.5 | 1.6 [1.4–1.7]*** | 1.4 [1.2–1.5]*** |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||||

| No (CCI score = 0) | 1,224 | 67 | 7,601.6 | 8.8 | 10,268 | 367 | 62,159.4 | 5.9 | 1.5 [1.3–1.7]*** | 1.9 [1.6–2.1]*** |

| Yes (CCI score ≥ 1) | 2,392 | 252 | 12,094.1 | 20.8 | 7,812 | 674 | 39,159.3 | 17.2 | 1.2 [1.1–1.3]** | 1.3 [1.2–1.4]*** |

The adjusted incidence rate ratios were calculated by multivariable analyses adjusting for the male sex, age, residency, income, and the presence of various comorbidities (except for the variable used for stratification). **P < .01; ***P < .0001. Cata = number of patients with cataract, CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index, CI = confidence interval, IR = incident rate, as expressed as cataract incidence per 1,000 patient-years, IRR = incidence rate ratio, NT$= New Taiwan dollar, PY = total patient-years, SA = sleep apnea.

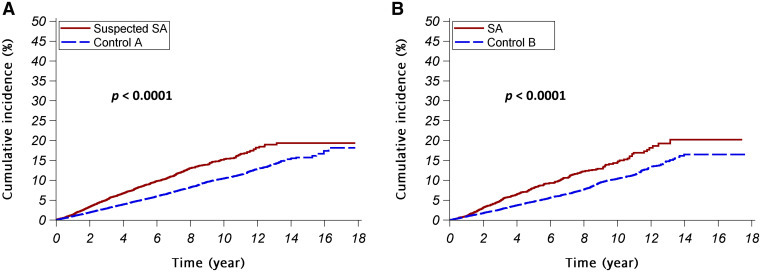

Figure 2 depicts the cumulative incidence of cataract in the patients with SA and corresponding control participants. In both study arm A and study arm B, the cumulative incidences of cataract were significantly higher in patients with SA than their matched control participants. Stratifying the participants by sex and age, the cumulative incidences of cataract were significantly higher in patients with SA than the controls in all strata (Figure S1 in the supplemental material).

Figure 2. Cumulative incidences of cataract.

The red continuous lines and blue dashed lines show the cumulative incidence of cataract for the patients with SA and the control participants, respectively. (A) Study arm A (suspected SA vs control A); (B) study arm B (SA vs control B). SA = sleep apnea.

Multivariable Cox regression analyses adjusting for sex, age, residency, income level, and comorbidities showed that SA was an independent risk factor for the occurrence of cataract (adjusted hazard ratios [95% CI]: 1.4 [1.3 – 1.6] and 1.4 [1.2 – 1.6] in study arms A and B, respectively) (Table S1 in the supplemental material and Figure S2 in the supplemental material). Stratified analyses revealed that SA remained an independent risk factor for incident cataract in nearly all strata (Figure S2 in the supplemental material).

We further investigated the contributing risk factors for cataract in patients with SA using multivariable Cox regression analyses (Table 3). Age was the strongest risk factor for cataract in patients with SA in both suspected SA and SA cohorts, while heart disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus were also risk factors for incident cataract. Male sex was noted as a protective factor for cataract in the suspected SA cohort, but its effect was insignificant in the SA cohort.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox regression analyses of the factors contributing to cataract in patients with SA.

| Patients in the Suspected SA Cohort | Patients in the SA Cohort | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal Model | Reduced Model* | Maximal Model | Reduced Model* | |||||

| HR [95% CI] | P | HR [95% CI] | P | HR [95% CI] | P | HR [95% CI] | P | |

| Sex (male vs female) | 0.8 [0.6–0.9] | .0011 | 0.7 [0.6–0.9] | .0001 | 0.9 [0.7–1.1] | .2234 | ||

| Age > 50 y (vs age ≤ 50 y) | 9.5 [7.8–11.7] | < .0001 | 9.9 [8.1–12.1] | < .0001 | 8.4 [6.3–11.1] | < .0001 | 8.8 [6.6–11.6] | < .0001 |

| Residency in northern Taiwan (vs in other areas) | 1.0 [0.8–1.1] | .5864 | 0.9 [0.7–1.2] | .5335 | ||||

| Higher income (> NT$24,000) (vs lower income) | 0.9 [0.7–1.0] | .0903 | 0.9 [0.7–1.1] | .1804 | ||||

| Presence of underlying diseases (vs absence of the diseases) | ||||||||

| Heart disease | 1.4 [1.0–1.8] | .0343 | 1.4 [1.1–1.8] | .0185 | 1.6 [1.1–2.3] | .0118 | 1.7 [1.2–2.4] | .0057 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.4 [0.8–2.2] | .2111 | 1.2 [0.6–2.4] | .6395 | ||||

| Major neurological disorder | 1.0 [0.8–1.3] | .7265 | 1.0 [0.8–1.4] | .8408 | ||||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.4 [1.2–1.7] | < .0001 | 1.4 [1.2–1.7] | < .0001 | 1.4 [1.1–1.8] | .0040 | 1.5 [1.2–1.8] | .0011 |

| Connective tissue disease | 1.2 [0.8–1.7] | .3087 | 0.9 [0.5–1.6] | .6784 | ||||

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1.0 [0.9–1.2] | .6601 | 1.1 [0.9–1.4] | .3859 | ||||

| Liver disease | 1.1 [0.9–1.3] | .2980 | 1.1 [0.9–1.4] | .4320 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.5 [1.2–1.8] | .0002 | 1.5 [1.3–1.8] | < .0001 | 1.4 [1.1–1.8] | .0209 | 1.4 [1.1–1.9] | .0091 |

| Renal disease | 1.0 [0.7–1.4] | .9747 | 0.8 [0.5–1.3] | .3900 | ||||

| Cancer | 1.3 [1.0–1.6] | .1074 | 1.2 [0.8–1.8] | .3816 | ||||

*Multivariable Cox regression model was built by a backward-variable selection method, eliminating variables with a P value > .05. CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio, NT$= New Taiwan dollar, SA = sleep apnea.

DISCUSSION

Cataract is a global issue of visual impairment in many places, especially in middle- and low-income countries.1–3,21 Finding a risk factor may delay the development of cataract for several years and decrease the need for surgical intervention.11 This large nationwide population-based cohort study revealed SA as a risk factor for cataract. We also found that age greater than 50 years, heart disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus were independent risk factors for developing cataract in patients with SA. As patients with SA have higher risk of perioperative complications while receiving ophthalmic surgeries,22 controlling these risk factors is important.

The development of cataract is a multifactorial process. The lens transparency may be disturbed by aging, hypoxic condition, oxidative stress, corticosteroid, ultraviolet-B exposure, and comorbidities.3,11,12,23 The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is important in the regulation of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol secretory dynamics. The recurrent episodes of apneas, intermittent hypoxia, and repetitive arousal from sleep may escalate serum cortisol level by disturbance of the hormone regulatory response and activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.24,25 The intermittent episodes of hypoxia and sudden arousal from sleep may also upregulate the sympathoadrenal activity, causing higher basal levels of circulating epinephrine and norepinephrine in patients with SA.26 The elevated serum catecholamines may further activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, leading to excessive secretion of corticosteroid hormones from the adrenal cortex.27 This perturbation in cortisol regulation and the over-responsiveness of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to stimulation may cause many pathological changes and sequelae in patients with SA, such as insulin resistance, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, and many ocular diseases.13,14,24 Raised endogenous basal circulatory cortisol level has been reported in patients with cataracts regardless of diabetic status and steroid use. The increased basal serum cortisol level in patients with SA may thus cause a directly detrimental effect on lens metabolism.28 As the pathological autonomic changes in patients with SA may be reversed after continuous positive airway pressure treatment,25 we believe that continuous positive airway pressure treatment might delay cataractogenesis in patients with SA.

The opacity of the lens is also strongly associated with oxidative stress, which may be aggravated by the aging process.3,29 The lens is vulnerable to the level of oxygen, and alteration of serum oxygenation may be a crucial factor in cataractogenesis. Hypoxia induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, which upregulates apoptotic unfolded protein response and reactive oxygen species, in human lens epithelial cells, resulting in their apoptosis.23 The apneic insults during sleep in patients with SA may lead to repeated oxygenic desaturation and reoxygenation sequences, and the chronic exposure to oxygen fluctuation may facilitate oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species production and induce the development of cataract.8,23

Diabetes mellitus is a well known risk factor of cataract.3,11,12,29 Hyperglycemia per se can induce excessive superoxide in the mitochondria, bringing about oxidative stress to lens.29 Together with fluctuation of oxygen saturation from SA, the oxidative stress may be further exacerbated in patients with SA plus diabetes mellitus and facilitate the development of cataract. It is therefore not surprising that diabetes mellitus was identified as an independent risk factor for developing cataract in both suspected SA and SA cohorts in this study.

Few previous studies have reported the association between chronic pulmonary disease and cataract. Several signaling pathways, especially the phosphoinositide-3-kinase–protein kinase B (PI3K-AKT) signaling pathway have been proposed to underlie the cross-talk between allergic asthma and cataract.30 Cigarette smoking is a shared risk factor for both cataract and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).3,11 Corticosteroid exposure has been associated with a higher prevalence of cataract in asthma and patients with COPD.31–33 Asthma, COPD, and smoking are all associated with increased oxidative stress in the blood, which may aggravate cataractogenesis in patients with SA.34 In the current study, chronic pulmonary disease, mainly consisting of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, was found as an independent risk factor for cataract in patients with SA.

The association between cataract and heart disease has not been extensively discussed previously. Using NHIRD, Hu et al found a higher incidence of ischemic heart disease in patients with cataract, particularly in the younger population.35 In our study, heart disease was found as an independent risk factor for cataract in patients with SA. The association between cataract and heart diseases, particularly in patients with SA, may need further investigation.

To the best our knowledge, this is the first large-scale nationwide population-based cohort study with very long follow-up period to investigate the risk of cataract in patients with SA. However, some limitations still exist in the present study. First, the diagnoses based on ICD-9-CM codes might be less accurate than those in standard clinical cohort studies. However, the coding accuracy of claims data from every medical institution is regularly and randomly checked by peer review for validation.19 To minimize the effect of coding errors, we only took into account codes presented in at least 2 outpatient claims or an inpatient claim. In addition to the analyses with the suspected SA cohort, we also performed another set of analyses with the SA cohort, whose members’ SA diagnosis remained after PSG. Both study arms revealed consistent findings. Second, it is impossible to discriminate OSA from central SA based on the ICD-9-CM codes. It was therefore difficult to differentiate whether central SA and OSA have the same influence on the risk of incident cataract. However, OSA accounts for > 90% of all patients with SA, so the association between cataract and SA may be similar to that between cataract and OSA.5,6 Third, the database lacks smoking history, a known risk factor for cataract. As the prevalence of smoking in Taiwan depends very much on age and sex,36 our stratified analyses and multivariable analyses adjusting for age and sex might have minimized the confounding effect of smoking. In addition, as a very small proportion of women in Taiwan smoke, the stratified analyses of female participants might reflect the effects of SA on incident cataract in nonsmokers. Fourth, in a retrospective study it is difficult to determine causality, because some potential confounding factors may be unknown. Although the temporal order might suggest a potential causative link between SA and cataract, further studies are still warranted to determine the cataractogenic effects of SA. Finally, the results of this study in Taiwan may not be applicable to other ethnicities or countries as socioeconomic statuses and health care systems vary.

In conclusion, the study demonstrated that SA was associated with higher risk of incident cataract, particularly in older patients and those having heart disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus. Together with many other vision-threatening ocular comorbidities in patients with SA, we suggest the necessity of regular ophthalmological examinations to save the vision of patients with SA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is based upon data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and managed by National Health Research Institutes (NHRI). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, or National Health Research Institutes. Due to legal and ethical restrictions, researchers should contact NHRI (https://nhird.nhri.org.tw/index.htm) for access to data after approval by their Institutional Review Board. The authors thank the Statistical Analysis Laboratory, the Department of Internal Medicine, and the Statistical Analysis Laboratory, Department of Medical Research, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital for their help.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CI

confidence interval

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- NHI

National Health Insurance

- NHIRD

National Health Insurance Research Database

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnography

- SA

sleep apnea

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. This research was funded by grants from Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital [KMUH108-8R13; KMUH109-9R14; KMUH109-9R50] and Kaohsiung Medical University [KMU-Q108005]. The authors have no relevant conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pascolini D , Mariotti SP . Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010 . Br J Ophthalmol. 2012. ; 96 ( 5 ): 614 – 618 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Batlle JF , Lansingh VC , Silva JC , Eckert KA , Resnikoff S . The cataract situation in Latin America: barriers to cataract surgery . Am J Ophthalmol. 2014. ; 158 ( 2 ): 242 – 250.e1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu YC , Wilkins M , Kim T , Malyugin B , Mehta JS . Cataracts . Lancet. 2017. ; 390 ( 10094 ): 600 – 612 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators ; on behalf of the Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study . Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study . Lancet Glob Health. 2021. ; 9 ( 2 ): e144 – e160 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Donovan LM , Kapur VK . Prevalence and characteristics of central compared to obstructive sleep apnea: analyses from the Sleep Heart Health Study Cohort . Sleep. 2016. ; 39 ( 7 ): 1353 – 1359 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bixler EO , Vgontzas AN , Ten Have T , Tyson K , Kales A . Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998. ; 157 ( 1 ): 144 – 148 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chin K , Hirai M , Kuriyama T , et al . Changes in the arterial PCO2 during a single night’s sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnea . Intern Med. 1997. ; 36 ( 7 ): 454 – 460 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pack AI , Pien GW . Update on sleep and its disorders . Annu Rev Med. 2011. ; 62 ( 1 ): 447 – 460 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Golbidi S , Badran M , Ayas N , Laher I . Cardiovascular consequences of sleep apnea . Lung. 2012. ; 190 ( 2 ): 113 – 132 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Svatikova A , Wolk R , Gami AS , Pohanka M , Somers VK . Interactions between obstructive sleep apnea and the metabolic syndrome . Curr Diab Rep. 2005. ; 5 ( 1 ): 53 – 58 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. West SK, Valmadrid CT. Epidemiology of risk factors for age-related cataract. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39(4):323–334. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12. Tan AG , Tham YC , Chee ML , et al . Incidence, progression and risk factors of age-related cataract in Malays: the Singapore Malay Eye Study . Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020. ; 48 ( 5 ): 580 – 592 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Santos M , Hofmann RJ . Ocular manifestations of obstructive sleep apnea . J Clin Sleep Med. 2017. ; 13 ( 11 ): 1345 – 1348 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu PK , Chang YC , Tai MH , et al . The association between central serous chorioretinopathy and sleep apnea: a nationwide population-based study . Retina. 2020. ; 40 ( 10 ): 2034 – 2044 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morsy NE , Amani BE , Magda AA , et al . Prevalence and predictors of ocular complications in obstructive sleep apnea patients: a cross-sectional case-control study . Open Respir Med J. 2019. ; 13 ( 1 ): 19 – 30 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen CM , Tsai MJ , Wei PJ , et al . Erectile dysfunction in patients with sleep apnea--a nationwide population-based study . PLoS One. 2015. ; 10 ( 7 ): e0132510 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chou PS , Chang WC , Chou WP , et al . Increased risk of benign prostate hyperplasia in sleep apnea patients: a nationwide population-based study . PLoS One. 2014. ; 9 ( 3 ): e93081 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kang JH , Keller JJ , Chen YK , Lin HC . Association between obstructive sleep apnea and urinary calculi: a population-based case-control study . Urology. 2012. ; 79 ( 2 ): 340 – 345 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheng KL , Huang JY , Su CL , Tung KC , Chiou JY . Cataract risk of neuro-interventional procedures: a nationwide population-based matched-cohort study . Clin Radiol. 2018. ; 73 ( 9 ):P 836.e17 – 836.e22 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deyo RA , Cherkin DC , Ciol MA . Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases . J Clin Epidemiol. 1992. ; 45 ( 6 ): 613 – 619 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Flaxman SR , Bourne RRA , Resnikoff S , et al. ; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study . Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990-2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Lancet Glob Health. 2017. ; 5 ( 12 ): e1221 – e1234 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cok OY , Seet E , Kumar CM , Joshi GP . Perioperative considerations and anesthesia management in patients with obstructive sleep apnea undergoing ophthalmic surgery . J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019. ; 45 ( 7 ): 1026 – 1031 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zheng XY , Xu J , Chen XI , Li W , Wang TY . Attenuation of oxygen fluctuation-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in human lens epithelial cells . Exp Ther Med. 2015. ; 10 ( 5 ): 1883 – 1887 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Henley DE , Russell GM , Douthwaite JA , et al . Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation in obstructive sleep apnea: the effect of continuous positive airway pressure therapy . J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009. ; 94 ( 11 ): 4234 – 4242 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carneiro G , Togeiro SM , Hayashi LF , et al . Effect of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and 24-h blood pressure profile in obese men with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome . Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008. ; 295 ( 2 ): E380 – E384 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elmasry A , Lindberg E , Hedner J , Janson C , Boman G . Obstructive sleep apnoea and urine catecholamines in hypertensive males: a population-based study . Eur Respir J. 2002. ; 19 ( 3 ): 511 – 517 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levy BH , Tasker JG . Synaptic regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and its modulation by glucocorticoids and stress . Front Cell Neurosci. 2012. ; 6 : 1 – 24 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Donnelly CA , Seth J , Clayton RM , Phillips CI , Cuthbert J , Prescott RJ . Some blood plasma constituents correlate with human cataract . Br J Ophthalmol. 1995. ; 79 ( 11 ): 1036 – 1041 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vinson JA . Oxidative stress in cataracts . Pathophysiology. 2006. ; 13 ( 3 ): 151 – 162 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao Y , Liu S , Li X , et al . Cross-talk of signaling pathways in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma and cataract . Protein Pept Lett. 2020. ; 27 ( 9 ): 810 – 822 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sweeney J , Patterson CC , Menzies-Gow A , et al. British Thoracic Society Difficult Asthma Network . Comorbidity in severe asthma requiring systemic corticosteroid therapy: cross-sectional data from the Optimum Patient Care Research Database and the British Thoracic Difficult Asthma Registry . Thorax. 2016. ; 71 ( 4 ): 339 – 346 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nath T , Roy SS , Kumar H , Agrawal R , Kumar S , Satsangi SK . Prevalence of steroid-induced cataract and glaucoma in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients attending a tertiary care center in India . Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2017. ; 6 ( 1 ): 28 – 32 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weatherall M , Clay J , James K , Perrin K , Shirtcliffe P , Beasley R . Dose-response relationship of inhaled corticosteroids and cataracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Respirology. 2009. ; 14 ( 7 ): 983 – 990 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rahman I , Morrison D , Donaldson K , MacNee W . Systemic oxidative stress in asthma, COPD, and smokers . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996. ; 154 ( 4 ): 1055 – 1060 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hu WS , Lin CL , Chang SS , Chen MF , Chang KC . Increased risk of ischemic heart disease among subjects with cataracts: a population-based cohort study . Medicine (Baltimore). 2016. ; 95 ( 28 ): e4119 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wen CP , Levy DT , Cheng TY , Hsu CC , Tsai SP . Smoking behaviour in Taiwan, 2001 . Tob Control. 2005. ; 14 ( Suppl 1 ): i51 – i55 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]