Abstract

Objectives

Autistic people experience poor physical and mental health along with reduced life expectancy compared with non-autistic people. Our aim was to identify self-reported barriers to primary care access by autistic adults compared with non-autistic adults and to link these barriers to self-reported adverse health consequences.

Design

Following consultation with the autistic community at an autistic conference, Autscape, we developed a self-report survey, which we administered online through social media platforms.

Setting

A 52-item, international, online survey.

Participants

507 autistic adults and 157 non-autistic adults.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Self-reported barriers to accessing healthcare and associated adverse health outcomes.

Results

Eighty per cent of autistic adults and 37% of non-autistic respondents reported difficulty visiting a general practitioner (GP). The highest-rated barriers by autistic adults were deciding if symptoms warrant a GP visit (72%), difficulty making appointments by telephone (62%), not feeling understood (56%), difficulty communicating with their doctor (53%) and the waiting room environment (51%). Autistic adults reported a preference for online or text-based appointment booking, facility to email in advance the reason for consultation, the first or last clinic appointment and a quiet place to wait. Self-reported adverse health outcomes experienced by autistic adults were associated with barriers to accessing healthcare. Adverse outcomes included untreated physical and mental health conditions, not attending specialist referral or screening programmes, requiring more extensive treatment or surgery due to late presentations and untreated potentially life-threatening conditions. There were no significant differences in difficulty attending, barriers experienced or adverse outcomes between formally diagnosed and self-identified autistic respondents.

Conclusions

Reduction of healthcare inequalities for autistic people requires that healthcare providers understand autistic perspectives, communication needs and sensory sensitivities. Adjustments for autism-specific needs are as necessary as ramps for wheelchair users.

Keywords: primary care, adult psychiatry, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study arose from a community-identified need to develop autism awareness training for healthcare providers and benefited from an autistic-led research team, including autistic medical doctors, using participatory methods.

To date, this large cross-sectional study is the first to explore the associations between barriers to accessing healthcare and self-reported adverse health outcomes for autistic adults.

As we used a convenience sample and self-report survey, generalisability of the data may be limited.

As the initial pilot questionnaire was undertaken in the UK, we did not include issues specific to other healthcare systems, such as cost or insurance, in this study.

Introduction

Autism is a common neurodevelopmental condition affecting 1%–2% of the population.1 While autism is lifelong and heterogeneous in presentation, most autistic people are adult, do not have intellectual disability and are likely to be undiagnosed.2 Doctors may underestimate the number of autistic patients under their care.3 4 Autistic adults have poor physical and mental health compared with the general population.5 Most medical conditions are more prevalent in the autistic population,6 7 including diabetes, hypertension and obesity.8 Autistic people experience premature mortality.9–11 Life expectancy is potentially reduced by 16–30 years, with increased mortality across almost all diagnostic categories.9 In-hospital mortality is also increased.12 Autistic people are over two times as likely to use emergency departments13 and to die after attending emergency care and three times as likely to require inpatient admission.14

Alongside increased health needs, autistic people report a greater likelihood that these needs are unmet.13 Pervasive, multifactorial barriers to healthcare access are experienced.15 Some are shared by other disabled people, but autistic patients experience additional autism-specific barriers.16 Patient–provider communication, sensory sensitivities, executive functioning/planning difficulties and prior negative experiences with healthcare providers are important barriers.17 18

In response to primary legislation19 and statutory guidance,20 the Royal College of General Practitioners developed an Autism Patient Charter.21 This recommended: staff awareness and training; autism friendly environment; reasonable adjustments following disclosure or clinical suspicion of autism; patient-tailored communications and behaviour-sensitive accommodations.21 Despite efforts to champion autism, proposals to formalise autism training18 22 and specific awareness-raising interventions,21 almost 40% of general practitioners (GPs) report no formal training in autism.22 They also report limited confidence in managing autistic patients.22 Greater autism awareness exists where GPs have personal knowledge of autism, either through a relative or friend on the autistic spectrum, or because they themselves are autistic.22 Communication skills training for healthcare providers may be the most pressing need.4 GPs22 and hospital specialists3 report difficulties communicating with autistic patients. Only 25% of primary healthcare providers reported high confidence in communicating with autistic adult patients or identifying and making necessary accommodations.4

This study primarily aimed to identify self-reported barriers to accessing primary healthcare faced by autistic adults with a focus on autism-specific communication, sensory issues and procedural considerations. Secondary aims included capturing self-reported adverse health outcomes and the associations between these and reported healthcare access barriers, adding a narrative frame to the existing evidence base around health disparities. This is to our knowledge the largest study of primary healthcare access barriers to date and benefits from a high degree of participatory design by the autistic community.

Methods

Conception and design

Here, we present part of a larger cross-sectional study. This work was inspired by a quality improvement project designed to inform autism training for local healthcare providers as part of an ‘Autism Friendly Town’ initiative by AsIAm, Ireland’s National Autism Charity.23 24 In 2018, MD attended Autscape,25 an annual conference by and for autistic people. Participants of all ages are welcome at Autscape, including those who are non-speaking, have high support needs or require full-time care, although the majority of attendees typically have low to moderate support needs. While there, MD distributed a qualitative questionnaire entitled ‘What do you wish your GP knew about autism?’ MD reviewed the 75 responses and grouped these under broad themes. That project formed the inspiration and basis for the study reported in this paper. Using the data gathered at Autscape, MD developed an online survey to investigate barriers to primary healthcare in a larger sample of autistic adults, compared with a non-autistic adult comparison group. Nine autistic adults assisted with refining the survey. The resulting survey contained a mix of quantitative questions and free comment boxes. Quantitative questions included yes–no responses, single-item and multiple-item selections from a list and Likert scales. We asked about specific barriers encountered accessing healthcare, reasons for delaying or avoiding a visit and difficulties booking, planning or waiting for a GP visit. We explored the challenges during a consultation, including communication, sensory and organisation issues as well as available social supports. We also explored the impact of such barriers including self-reported consequences of failure to access healthcare and the reasonable adjustments to standard care which facilitate access. We used Google Forms to host the survey.

Piloting and refinement

We piloted the survey in 2018. Preliminary analysis revealed a recurring theme of total non-engagement with healthcare providers, despite expressed healthcare needs. Consequently, we altered the survey to add response options applicable to non-attenders. Our research team, comprising autistic and non-autistic GPs, experienced academics and other autistic individuals, adapted and refined the survey into its final 52-item form.

Sampling, recruitment and data collection

Autistic adults were recruited using a convenience sampling approach, through Twitter, Facebook and the AsIAm website. We recruited non-autistic controls (without autistic children) through personal and professional contacts of research team members, local area groups and parenting groups on social media. Recruitment took place in August 2019. We provided participant information, with informed consent implied through subsequent completion of the questionnaire. We asked respondents, particularly those who were parents, to respond specifically about seeking healthcare for themselves. For those identifying as autistic, we asked if they were formally diagnosed or self-identified.

Data analysis

We used the statistical package ‘R’ to assess significance of between-group associations using a test of proportions and a Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test. Participants who skipped questions were omitted from the analyses of those questions. We intend to present our qualitative results elsewhere.

Patient and public involvement

Our study was conducted by an autistic-led research team including autistic medical doctors, using participatory methods. In addition, nine autistic individuals assisted with developing and refining the survey into its final form.

Results

Participants

We are reporting 664 responses to the online survey: 507 autistic adults and 157 non-autistic adults (table 1). Unless otherwise specified, results relate to primary care.

Table 1.

Participant data

| Autistic | Non-autistic | |

| Participants (n) | 507 | 157 |

| Age | ||

| Median (range) | 38 (17–73) | 38 (18–70) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 99 (20%) | 16 (10%) |

| Female | 311 (62%) | 132 (85%) |

| Non-binary | 83 (17%) | 7 (5%) |

| Prefer not to say | 9 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| Location | ||

| UK | 330 (65%) | 67 (43%) |

| Ireland | 77 (15%) | 63 (40%) |

| North America | 44 (9%) | 20 (13%) |

| Other | 56 (11%) | 7 (4%) |

| Formal diagnosis of autism | 77% | |

| By psychiatrist | 25% | |

| By clinical psychologist | 48% | |

| By multidisciplinary team | 26% | |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| Median (range) | 33 (2–67) |

Barriers to access

The most common reason for a GP visit was a physical condition or illness in both groups (86% vs 92%, n.s.). Autistic individuals were more likely to attend for mental health difficulties (61% vs 27%, difference 34%, 95% CI (25.2% to 42.3%), p<0.001). Twenty-two per cent of the autistic respondents usually attended for issues directly related to autism. Compared with 37% of non-autistic respondents, 80% of autistic respondents reported difficulty visiting a GP when needed (difference 43%, 95% CI (34.4% to 51.9%), p<0.001). While difficulty deciding if symptoms warrant a visit was a barrier for both groups (72% vs 65%, n.s.), the most notable difference related to difficulties using the telephone to book an appointment (62% vs 16%). Not feeling understood was a reason to avoid or delay for 56% of autistic respondents compared with 13% of non-autistic respondents. Difficulty communicating with the doctor during the appointment was a barrier for 53% of the autistic group but only 6% of non-autistic respondents. See online supplemental table 1 for specific barriers in order of frequency.

bmjopen-2021-056904supp001.pdf (77KB, pdf)

Communication

Alongside difficulty using the telephone, not feeling understood and difficulty communicating with the doctor, autistic respondents reported difficulty communicating with reception staff more often than non-autistic respondents (46% vs 8%, difference 38%, 95% CI (31.5% to 44.6%), p<0.001). Fifty nine per cent of autistic respondents reported difficulty communicating during a consultation ‘all the time’ or ‘frequently’ compared with 12% of non-autistic respondents (p<0.001). Seventy eight per cent of autistic adults reported that ‘anxiety makes it harder to communicate’

Autistic respondents reported avoiding the telephone (78%), voicemail (61%) and face-to-face verbal communication (30%). Forty one per cent reported that it is ‘easier for me to communicate in writing’ (table 2).

Table 2.

Communication barriers

| Autistic n (%) | Non-autistic n (%) | Difference (95% CI) | P value | |

| Reasons to avoid or delay GP visit (communication) | ||||

| Difficulty using the telephone to book an appointment | 314 (62) | 25 (16) | 46% (38.5% to 53.5%) | <0.001 |

| Not feeling understood | 283 (56) | 21 (13) | 42% (35.2% to 49.7%) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty communicating with the doctor during the appointment | 269 (53) | 10 (6) | 47% (40.5% to 52.9%) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty communicating with the reception staff | 235 (46) | 13 (8) | 38% (31.5% to 44.6%) | <0.001 |

| Communication preferences | ||||

| Telephone generally avoided where possible | 395 (78) | 59 (38) | 40% (31.5% to 49.1%) | <0.001 |

| Voicemail generally avoided where possible | 311 (61) | 61 (39) | 23% (13.3% to 31.6%) | <0.001 |

| Verbal, face-to-face communication generally avoided where possible | 152 (30) | 12 (8) | 22% (16.2% to 28.5%) | <0.001 |

| It is easier for me to communicate in writing | 208 (41) | 13 (8) | 33% (26.3% to 39.2%) | <0.001 |

| Communication challenges | ||||

| Anxiety makes it harder to communicate | 395 (78) | 42 (23) | 51% (42.9% to 59.4%) | <0.001 |

| Sensory issues make communication more difficult | 156 (31) | 2 (1) | 30% (24.7% to 34.3%) | <0.001 |

| I need extra time to process what is being said | 286 (56) | 12 (8) | 49% (42.4% to 55.2%) | <0.001 |

| I can’t describe my pain or symptoms accurately | 272 (54) | 36 (23) | 31% (22.4% to 39.0%) | <0.001 |

| Verbal communication is difficult | 234 (46) | 11 (7) | 39% (32.8% to 45.5%) | <0.001 |

| I express emotions differently for example, I can appear angry when I am afraid or in pain | 227 (45) | 6 (4) | 41% (35.3% to 46.6%) | <0.001 |

| I have difficulty prioritising when describing medical symptoms | 333 (66) | 34 (22) | 44% (36.0% to 52.1%) | <0.001 |

| I need to give the whole story and not leave anything out | 332 (66) | 18 (12) | 54% (47.1% to 60.9%) | <0.001 |

| None of the above (communication) | 11 (2) | 58 (37) | −35% (−42.8% to −26.7%) | <0.001 |

GP, general practitioner.

Sensory processing

The waiting room environment was a barrier for 51% of autistic respondents, but only 8% of non-autistic respondents. Specific sensory barriers are detailed in table 3. Sensory issues made communication more difficult for 31% of the autistic group (see table 2). Only 10% of autistic respondents marked ‘none of the above’ to sensory questions compared with 71% of non-autistic respondents.

Table 3.

Sensory barriers

| Autistic n (%) | Non-autistic n (%) | Difference (95% CI) | P value | |

| Reasons to avoid or delay GP visit (sensory) | ||||

| The waiting room environment | 256 (51) | 12 (8) | 42.8% (36.4% to 49.3%) | <0.001 |

| Specific sensory challenges | ||||

| Noise in the waiting room from other patients | 319 (63) | 19 (12) | 51% (43.8% to 57.8%) | <0.001 |

| Crowded waiting area | 299 (59) | 22 (14) | 45% (37.6% to 52.3%) | <0.001 |

| Bright or fluorescent lights | 268 (53) | 14 (9) | 44% (37.3% to 50.6%) | <0.001 |

| Uncomfortable furniture | 195 (39) | 11 (7) | 32% (25.2% to 37.7%) | <0.001 |

| Unexpected touch | 193 (38) | 9 (6) | 32% (26.3% to 38.3%) | <0.001 |

| Music playing in the waiting room | 172 (34) | 9 (6) | 28% (22.3 to 34.1%) | <0.001 |

| Smells in the waiting room | 171 (34) | 8 (5) | 29% (22.9% to 34.4%) | <0.001 |

| Touch during examination | 160 (32) | 11 (7) | 25% (18.5% to 30.7%) | <0.001 |

| Noise from the reception desk | 140 (28) | 4 (3) | 25% (20.0% to 30.1%) | <0.001 |

| Smells in the doctor’s office | 104 (21) | 6 (4) | 17% (11.7% to 21.7%) | <0.001 |

| None of the above (sensory) | 51 (10) | 112 (71) | −61% (−69.2% to −53.3%) | <0.001 |

GP, general practitioner.

Perceived stigma

Only 3% of autistic respondents stated they did not feel anxious going to the doctor, compared with 33% of non-autistic respondents (difference 30%, 95% CI (−37.7% to −21.8%) p<0.001). Autistic respondents reported being ‘concerned I won’t be taken seriously when I describe my symptoms’ (67%); worried about ‘wasting the doctor’s time’ (66%) and ‘being considered a hypochondriac’ (65%). They also reported difficulty ‘asking for help’ (63%) and ‘discussing mental health’ (59%). Autistic respondents reported that unusual behaviour or stimming elicited negative reactions from other patients (15%), reception staff (9%) or medical staff (7%) (online supplemental table 2).

Planning and organising

Autistic respondents reported difficulties with summarising when describing medical problems, with 66% noting the ‘need to give the whole story and not leave anything out’ compared with 12% of non-autistic respondents (difference 54%, 95% CI (47.1% to 60.9%), p<0.001). Autistic respondents reported difficulties with organisation and planning for healthcare, including difficulties ‘making an appointment in advance’ (59%), ‘prioritising my health issues’ (58%) and ‘making changes to my lifestyle or habits’ (56%). Forty five per cent reported forgetting a medical appointment and 30% had attended on the wrong day (online supplemental table 3).

Predictability and control

Autistic respondents reported more difficulty with uncertainty than non-autistic respondents. Particular difficulties included not knowing the wait duration (70% vs 30%, difference 40%, 95% CI (31.5% to 48.7%), p<0.001), what would happen during the consultation (63% vs 16%, difference 47%, 95% CI (39.7% to 54.7%), p<0.001), which doctor they would see (58% vs 24%, difference 33%, 95% CI (25.0% to 41.8%), p<0.001) and the consultation length (40% vs 8%, difference 32%, 95% CI (25.6% to 38.4%) p<0.001).

Support needs

Autistic adults reported physical mobility needs (16%) and unmet support needs in primary care, for example, ‘needing a support person to come with me’ (21%). This extended to secondary care: 17% had no one to support unexpected hospital admission, collection from hospital (20%) or home care following discharge (26%) (online supplemental table 4).

Adverse consequences

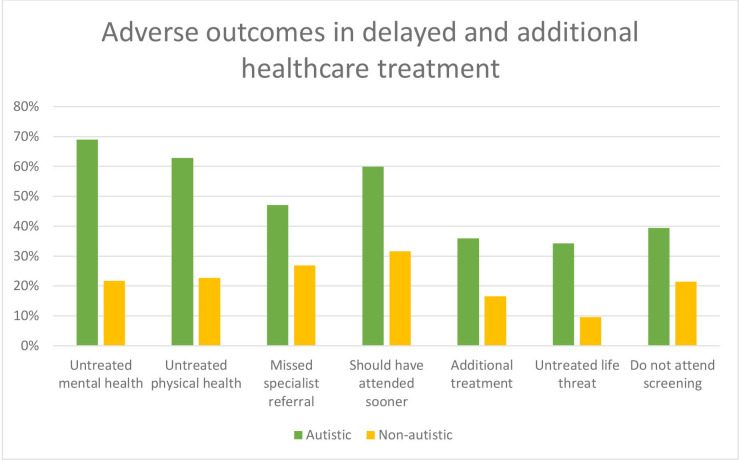

Autistic respondents reported adverse consequences more frequently than non-autistic respondents, including untreated mental (69%) and physical (63%) health conditions. Notably, 60% were told they ‘should have seen a doctor sooner’ and 47% ‘did not attend referral to a specialist’. Thirty-six per cent ‘required more extensive treatment or surgery’ and 34% did not access treatment for a ‘potentially serious or life-threatening condition’. Additionally, they were less likely to ‘attend on schedule for screening programmes’ than the non-autistic respondents (39% vs 21%, difference 18%, 95% CI (9.8% to 26.2%), p<0.001) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adverse healthcare outcomes. For all comparisons between autistic and non-autistic groups p<0.001.

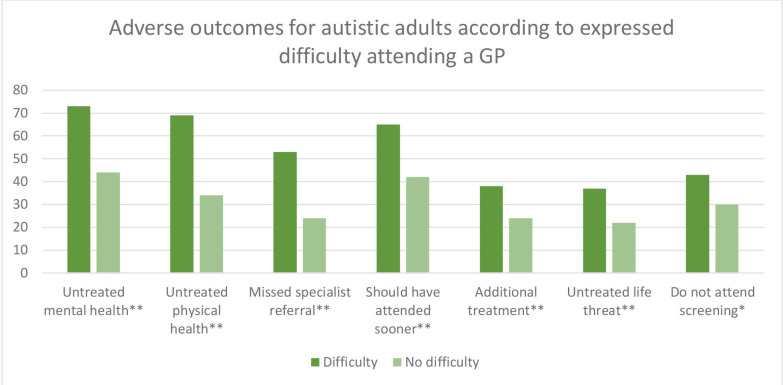

Compared with autistic respondents who had no difficulty visiting a doctor, those who experienced difficulty (80%) reported more untreated mental and physical health conditions (p<0.001). They were also more likely to not attend specialist referral (p<0.001), to need more extensive treatment (p=0.009), to experience untreated life-threatening conditions (p=0.006) and to not attend screening (p=0.028) (figure 2). Four per cent of autistic respondents reported no access to primary healthcare and did not attend any doctor at all. This group differed from the non-autistic respondents who reported no access to primary healthcare (5%) in two areas: all had difficulty visiting the doctor when needed, compared with 50% of non-attending non-autistic respondents (p=0.002); and 95% of autistic non-attenders had experienced at least one delayed treatment outcome, compared with 43% of non-attending, non-autistic respondents (p=0.01). There were no significant differences in difficulty attending a GP, the barriers experienced or adverse outcomes between formally diagnosed and self-identified autistic respondents.

Figure 2.

Adverse outcomes according to difficulty attending a GP. **p<0.001 *p<0.05. y-axis=N. GP, general practitioner.

Facilitators

While most respondents (67% vs 65%) reported booking an appointment online would facilitate access, autistic patients selected a need to ‘email my doctor in advance with a description of the issue I need to discuss’ (62%), ‘wait in a quiet place or outside until my turn’ (56%) and ‘book an appointment by text’ (41%). Some autistic individuals would benefit if they ‘could book the first or last appointment’ (41%) or had a ‘sensory box available in the waiting room’ (16%) (online supplemental table 5).

Despite the outlined difficulties of visiting their doctor, autistic individuals felt that their relationship with their GP was ‘very important’ or ‘important’ significantly more than non-autistic respondents (70% vs 56%, p=0.001), but only 33% of autistic respondents reported a good relationship with their doctor (p<0.001). Only 62% of autistic individuals reported that their doctor knew they were autistic. Twenty two per cent were unsure, whereas 16% had not disclosed their diagnosis. Autistic respondents appreciated GPs who ask direct questions, give clear explanations, are honest about not understanding autism but know that autism is not a mental illness.

Geographical variations

Some barriers to access for autistic respondents varied by geographical location (UK vs elsewhere in the world). Autistic respondents from the UK had more difficulty using the telephone to book appointments (66% vs 54%, p=0.012), more difficulty communicating with reception staff (52% vs 37%, p=0.002) and were less likely to experience no barriers to access at all (0.3% vs 2.8%, p=0.038). Autistic respondents from the UK also found it harder to see a known or preferred doctor (58% vs 29%, p<0.001), reported longer waits to get appointments (59% vs 33%, p<0.01) and found their online appointment booking systems more confusing (26% vs 10%, p<0.001). However, they were less likely to report no access to online booking systems compared with those from elsewhere in the world (26% vs 42%, p<0.001). There were no other significant differences for autistic respondents by geographical location.

There was only one significant geographical variation in self-reported adverse outcomes. For autistic respondents, those in the UK were less likely than those from elsewhere in the world to miss/not attend specialist referrals (43% vs 55%, p=0.019).

Associations between barriers and outcomes for autistic respondents

Table 4 outlines associations between reported barriers and outcomes for autistic respondents. There were no significant associations between any adverse outcomes and difficulty deciding if symptoms warrant a GP visit, not having an online booking system, having a confusing online booking system, having a long wait to get an appointment or having enough time to visit a doctor. In contrast, difficulty communicating with reception staff and difficulty communicating with the doctor during appointments were both significantly associated with all adverse outcomes.

Table 4.

Barriers and outcomes associations for autistic respondents

| Untreated mental health condition | Untreated physical health condition | Specialist referral missed | Told they should have presented sooner | More extensive treatment or surgery required | Serious or life-threatening condition | |

| Difficulty using the telephone to book an appointment | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.036 | p=0.015 | n.s. | p=0.007 |

| Difficulty with advance planning | p=0.020 | p=0.032 | p<0.001 | p=0.030 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Difficulty communicating with reception staff | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.008 | p<0.001 | p=0.041 | p=0.004 |

| Difficulty communicating with the doctor during the appointment | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.003 | p=0.003 | p=0.002 |

| The waiting room environment | p=0.007 | p<0.001 | n.s. | p=0.010 | p<0.001 | n.s |

| Inability to see a known or preferred doctor | p<0.001 | p=0.003 | n.s. | p=0.027 | n.s. | n.s |

| Waiting to see the doctor is too difficult | p=0.018 | p=0.001 | n.s. | n.s. | p=0.026 | n.s. |

| Not feeling understood | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | n.s. | n.s. | p=0.026 |

| Needing a support person to come with me | n.s. | p=0.002 | p=0.004 | n.s. | p=0.009 | p=0.002 |

n.s, not significant.

Difficulty using the telephone to book an appointment was significantly associated with all adverse outcomes apart from having to undergo more extensive treatment or surgery than if they had attended sooner. Challenges with the waiting room environment were significantly associated with all adverse outcomes apart from missing specialist referrals and having a potentially serious or life-threatening condition for which they did not access treatment. Difficulty planning an appointment in advance was significantly associated with all adverse outcomes apart from having a potentially serious or life-threatening condition for which they did not access treatment, and having to undergo more extensive treatment or surgery than if they had attended sooner. Needing a support person to attend appointments was significantly associated with all adverse outcomes apart from having had a mental health condition remain untreated due to difficulties accessing healthcare and being told they should have presented sooner. Not feeling understood was significantly associated with all adverse outcomes apart from being told they should have presented sooner and having to undergo more extensive treatment or surgery than if they had attended sooner.

The inability to see a known or preferred doctor was significantly associated with having both untreated mental and physical health conditions. It was also significantly associated with being told they should have presented sooner. Finding waiting to see a doctor too difficult was significantly associated with having both untreated mental and physical health conditions. It was also significantly associated with having to undergo more extensive treatment or surgery than if they had attended sooner.

Reporting no barriers to access healthcare had no significant associations with any of the adverse outcomes.

Discussion

Our study describes the results of a survey of autistic adults and compares their experiences with non-autistic adults. It highlights barriers faced by autistic people accessing and engaging with primary healthcare. In our study, these included greater difficulties deciding when to seek care, reluctance to bother their GP, difficulties planning appointments and greater communication difficulties—with particular emphasis on telephone use. Communication was also impaired by anxiety and sensory issues. We linked those barriers to self-reported adverse outcomes. Our data indicated that autistic people may present for healthcare later in the natural course of an illness. Autistic participants reported reduced attendance for screening, late presentations, missed opportunities for early detection and more extensive therapy being required. They also delayed or avoided healthcare because they did not feel understood by their doctors. Furthermore, a substantial minority of autistic adults did not disclose their autism diagnosis, which may impede identification of their autism-specific needs. These barriers may have real consequences, as evidenced in reduced life expectancy, and higher levels of physical and mental health conditions among autistic people.

Comparison with the existing literature

This study confirms the findings of Vohra,14 Raymaker16 and several recent reviews,15 17 26 which all identified three groups of barriers: (1) patient-level factors; (2) provider-level factors and (3) system-level factors. Our study stratifies individual barriers from the perspective of autistic individuals. We couple these barriers to self-reported adverse consequences, highlighting factors that may lead to excess morbidity and mortality in the autistic population.

Strengths and limitations

Our study arose from a community-identified need to develop autism awareness training for healthcare providers. It benefited from an autistic-led research team, including autistic doctors, using participatory methods. Our study provided a unique picture of autistic adults’ healthcare experiences, including those entirely excluded from healthcare due to access barriers. In particular, we highlighted the difficulties with using the telephone which is a distilled, concentrated essence of verbal communication.

As we used a convenience sample and self-report survey, generalisability of the data may be limited. Respondents required the ability to complete the survey, which excluded those with reduced ability to self-report. While we did not set out to create a validated tool, our survey may have benefited from some validity and reliability testing. As the initial quality improvement questionnaire was undertaken in the UK, we did not include issues specific to other healthcare systems, such as cost or insurance. Our analyses did not account for potential confounding factors, such as ethnicity or socioeconomic status. Female participants were over-represented in both groups, which is not unusual for online surveys, but it is interesting given the higher rate of autism diagnosis in men. While we noted significant gender differences in relation to non-binary participants, these participants were almost all autistic and we were, therefore, unable to attribute differences to gender identity or autism with any degree of certainty. Furthermore, as this is a cross-sectional study, while we can identify associations, we cannot confirm causality.

Implications for research

Our study suggests a need for personalised approaches to healthcare access. A prior study investigated using a previsit telephone call to identify individualised accommodations.27 Our data suggest that this could be problematic for autistic adults. The AASPIRE Healthcare Toolkit28 includes a publicly available online programme, which generates a computerised report of required healthcare accommodations. Adaptation of such a toolkit in NHS General Practice should be considered and researched. Social care interventions and healthcare facilitators in general practice have shown benefit with a vulnerable population,29 similar approaches could benefit an autistic population. The significant difficulties among the small number of autistic people not registered with any GP indicate a need for further research into this group.

Implications for clinical practice

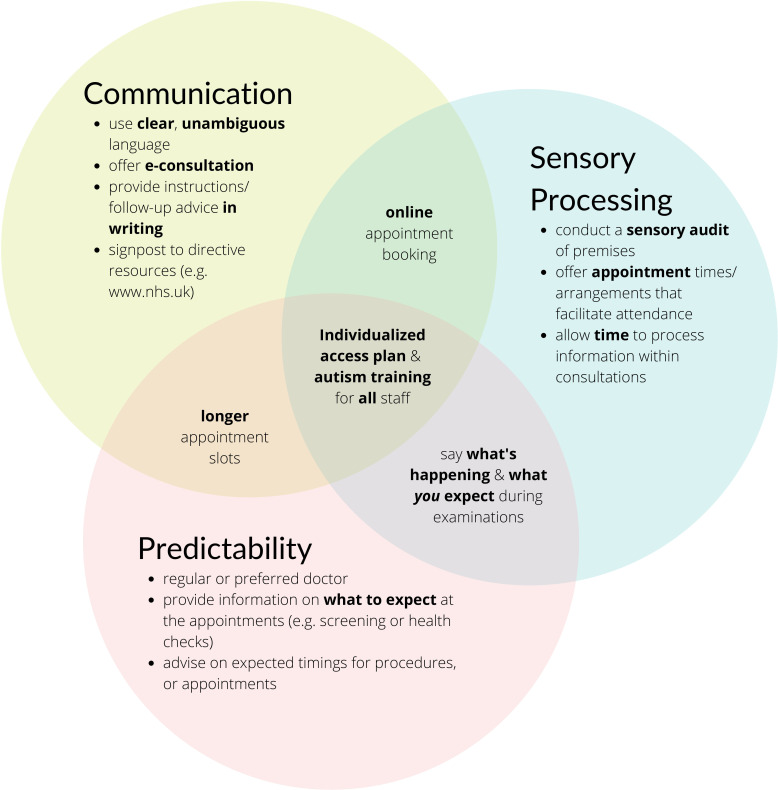

Based on online supplemental table 5 and the lived experience of the autistic members of our research team, figure 3 outlines our proposed elements of an autism friendly practice. Such adjustments may minimise anxiety, manage sensory issues and ensure mutual understanding—promoting clear, unambiguous communication. Autism friendly practices should employ a personalised approach, with a healthcare access needs assessment and, where possible, a specialist liaison nurse or facilitator.

Figure 3.

Autism friendly general practice.

Implications for policy

Given the identified barriers, the extension of annual health checks to autistic adults30 31 and the recently announced Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training in Learning Disability and Autism32 are welcome. These will likely bring important benefits provided they are informed by the autistic community and autistic healthcare providers. Autism registers in GP practice have been recommended.33 34 The success of such initiatives will likely depend on greater awareness by medical practitioners of autistic culture and communication needs. Specific training for GPs during core training and continuing professional development may be beneficial. GPs with a special interest in autism should be facilitated to develop their skills, but management of general health needs and co-occurring conditions fall within the remit of every GP. Implementing existing autism legislation or development where lacking is required in order to reduce health inequities for autistic people.

Conclusions

Autistic people face barriers accessing the healthcare system, followed by difficulties interacting with healthcare providers, which may contribute to known healthcare disparities, including increased morbidity and mortality. Our study has highlighted a variety of specific barriers to accessing primary healthcare for autistic adults, including use of the telephone to book appointments, not feeling understood, and difficulty communicating with doctors as well as sensory and organisational issues, which impede healthcare access. We identified a variety of significant associations between self-reported barriers to healthcare access and adverse outcomes for autistic respondents. One of our most impactful findings was the lack of any significant differences between formally diagnosed and self-identified autistic respondents in difficulty attending a GP, barriers experienced or self-reported adverse healthcare outcomes. Progress towards eliminating healthcare disparities for autistic people may be achieved by understanding the healthcare experiences and access barriers for this vulnerable patient group. These barriers represent not so much a failure to deliver or to avail of healthcare, but a lack of intersection between the communication patterns of autistic healthcare users and non-autistic providers. Reasonable accommodations are legally35 and morally required. Adjustments for communication needs are as necessary for autistic people as ramps for wheelchair users.

bmjopen-2021-056904supp002.pdf (92.5KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Professor Louise Gallagher for her guidance during the early stages of this project. We acknowledge the input received from the autistic adult community recruited via local groups and online contacts during the development of the online survey. Assistance with content, structure and proofreading of the surveys was received from nine autistic adults in Ireland and the UK. We received assistance from members of peer support group ‘Autistic Doctors International’. We also thank Dr David Hillebrandt, Dr Natalie Teasdale, Elaine McGoldrick and Karen Leneh Buckle for their assistance during this project.

Footnotes

Twitter: @AutisticDoctor, @Autistic_Doc

Contributors: Conception and design of study: MD, SN, JO'S, with contributions from those listed in acknowledgements. Acquisition of data: MD, SN, JO'S. Analysis of data: SN, MD, SCKS. Interpretation of data: MD, SN, JO'S, LC, MJ, WC, SCKS. Drafting and revising the manuscript: MD, SN, JO'S, LC, MJ, WC, SCKS. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published: MD, SN, JO'S, LC, MJ, WC, SCKS. MD is the Guarantor of this work.

Funding: We are grateful to AsIAm, Ireland’s National Autism Charity and Scally’s SuperValu, Clonakilty, for the funding to enable open access publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by SJH/TUH Joint Research and Ethics Committee REC: 2019-06 Chairman’s Action (17). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Data CDC . Statistics. autism spectrum disorder. Resource document. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

- 2.Royal College of Psychiatrists . The psychiatric management of autism in adults (CR228). Available: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/campaigning-for-better-mental-health-policy/college-reports/2020-college-reports/cr228 [Accessed 24 Jul 2021].

- 3.Zerbo O, Massolo ML, Qian Y, et al. A study of physician knowledge and experience with autism in adults in a large integrated healthcare system. J Autism Dev Disord 2015;45:4002–14. 10.1007/s10803-015-2579-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolaidis C, Schnider G, Lee J, et al. Development and psychometric testing of the AASPIRE adult autism healthcare provider self-efficacy scale. Autism 2021;25:767–73. 10.1177/1362361320949734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rydzewska E, Hughes-McCormack LA, Gillberg C, et al. General health of adults with autism spectrum disorders – a whole country population cross-sectional study. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2019;60:59–66. 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croen LA, Zerbo O, Qian Y, et al. The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism 2015;19:814–23. 10.1177/1362361315577517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue Ming, Brimacombe M, Chaaban J, et al. Autism spectrum disorders: concurrent clinical disorders. J Child Neurol 2008;23:6–13. 10.1177/0883073807307102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flygare Wallén E, Ljunggren G, Carlsson AC, et al. High prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and obesity among persons with a recorded diagnosis of intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder. J Intellect Disabil Res 2018;62:269–80. 10.1111/jir.12462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirvikoski T, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Boman M, et al. Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2016;208:232–8. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang YIJ, Srasuebkul P, Foley K-R, et al. Mortality and cause of death of Australians on the autism spectrum. Autism Res 2019;12:806–15. 10.1002/aur.2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilder D, Botts EL, Smith KR, et al. Excess mortality and causes of death in autism spectrum disorders: a follow up of the 1980s Utah/UCLA autism epidemiologic study. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43:1196–204. 10.1007/s10803-012-1664-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akobirshoev I, Mitra M, Dembo R, et al. In-hospital mortality among adults with autism spectrum disorder in the United States: a retrospective analysis of US hospital discharge data. Autism 2020;24:177–89. 10.1177/1362361319855795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, et al. Comparison of healthcare experiences in autistic and non-autistic adults: a cross-sectional online survey facilitated by an academic-community partnership. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:761–9. 10.1007/s11606-012-2262-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U. Emergency department use among adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord 2016;46:1441–54. 10.1007/s10803-015-2692-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh C, Lydon S, O’Dowd E, et al. Barriers to healthcare for persons with autism: a systematic review of the literature and development of a taxonomy. Dev Neurorehabil 2020;8:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raymaker DM, McDonald KE, Ashkenazy E, et al. Barriers to healthcare: instrument development and comparison between autistic adults and adults with and without other disabilities. Autism 2017;21:972–84. 10.1177/1362361316661261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason D, Ingham B, Urbanowicz A, et al. A systematic review of what barriers and facilitators prevent and enable physical healthcare services access for autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord 2019;49:3387–400. 10.1007/s10803-019-04049-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogan V, Lake JK, Tint A, et al. Tracking health care service use and the experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability: a longitudinal study of service rates, barriers and satisfaction. Disabil Health J 2017;10:264–70. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Autism Act UK . HM Government, 2009. Available: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2009/15/contents

- 20.Department of Health . Implementing fulfilling and rewarding lives. Statutory guidance for local authorities and NHS organisation to support implementation of the autism strategy. London: Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckley C. Making your practice autism friendly. InnovAiT 2017;10:327–31. 10.1177/1755738017692002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unigwe S, Buckley C, Crane L, et al. GPs’ confidence in caring for their patients on the autism spectrum: an online self-report study. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e445–52. 10.3399/bjgp17X690449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AsIAm . A first for Ireland with Clonakilty becoming Ireland’s first autism friendly town, 2016. Available: https://asiam.ie/clonakilty-autism-friendly-town/

- 24.AsIAm . Are you ready to make your Clonakilty commitment for Autism?, 2020. Available: https://asiam.ie/asiam-public-sector-training/autism-friendly-communities/

- 25.The Autscape Organisation . Autscape 2018: exploring inclusion. Tonbridge, Kent, 2018. Available: http://www.autscape.org/2018/

- 26.Bradshaw P, Pellicano E, van Driel M, et al. How can we support the healthcare needs of autistic adults without intellectual disability? Curr Dev Disord Rep 2019;6:45–56. 10.1007/s40474-019-00159-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saqr Y, Braun E, Porter K, et al. Addressing medical needs of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders in a primary care setting. Autism 2018;22:51–61. 10.1177/1362361317709970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, et al. The development and evaluation of an online healthcare toolkit for autistic adults and their primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1180–9. 10.1007/s11606-016-3763-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abel J, Kingston H, Scally A, et al. Reducing emergency hospital admissions: a population health complex intervention of an enhanced model of primary care and compassionate communities. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e803–10. 10.3399/bjgp18X699437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Chapter 3: Learning disability and Autism. In: Long term plan [London], 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/chapter-3-further-progress-on-care-quality-and-outcomes/a-strong-start-in-life-for-children-and-young-people/learning-disability-and-autism/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harper G, Smith E, Parr J. Autistica action briefing: health checks. Available: https://www.autistica.org.uk/downloads/files/Autistica-Action-Briefing-Health-Checks.pdf

- 32.Health Education England . Partners announced to deliver the Oliver McGowan mandatory learning disability and autism training for all health and social care staff, 2020. Available: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/news-blogs-events/news/partners-announced-deliver-oliver-mcgowan-mandatory-learning-disability-autism-training-all-health

- 33.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . The practice establishes and maintains a register of all patients with a diagnosis of autism [London] ([NM153]]), 2017. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/standards-and-indicators/qofindicators/the-practice-establishes-and-maintains-a-register-of-all-patients-with-a-diagnosis-of-autism

- 34.Westminster Commission on Autism . A spectrum of obstacles an inquiry into access to healthcare for autistic people. Available: https://westminsterautismcommission.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/ar1011_ncg-autism-report-july-2016.pdf

- 35.Great Britain . Equality act 2010. London: Stationary Office, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-056904supp001.pdf (77KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-056904supp002.pdf (92.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.