Abstract

Objective

To investigate the efficacy and safety of the antithrombotic therapy using the oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban and clopidogrel in Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome complicated with atrial fibrillation after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Methods

A total of 100 patients were selected. Patients were randomly divided into two groups: the treatment group (rivaroxaban group) received a therapy of rivaroxaban and clopidogrel. The control group (warfarin group) receivied a combined treatment of warfarin, clopidogrel, and aspirin. The primary outcome endpoint was evaluated based on the adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events within 12 months.

Results

A total of 8 (8.00%) main adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events occurred during the 12 months of follow-up, including 5 (9.80%) in the warfarin group and 3 (6.10%) in the rivaroxaban group. The risk of having main adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in the two groups was comparable (P = 0.479). A total of 9 patients (9.00%) were found to have bleeding events, among which 8 patients (15.7%) were in the warfarin group, whereas only 1 patient (2.00%) was in the rivaroxaban group. Therefore, the risk of bleeding in the warfarin group was significantly higher than that in the rivaroxaban group (P = 0.047).

Conclusions

In Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome complicated with atrial fibrillation, the efficacy of the dual therapy of oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban plus clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention was similar to that of the traditional triple therapy combined with warfarin, aspirin and clopidogrel, but it has a better safety property, which has potential to widely apply to antithrombotic therapy after PCI

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, percutaneous coronary intervention, oral anticoagulant, rivaroxaban, warfarin, Chinese patient

Impact on Practice Statements

This study provides a better alternative for the drug therapy of patients with atrial fibrillation combined with acute coronary syndrome after PCI.

Combination therapy with rivaroxaban and clopidogrel can be used to achieve good antithrombotic therapy while reducing the risk of complications.

It may be possible to improve the prognosis of these patients at high bleeding risk, thereby reducing the medical burden on society.

Background

Coronary heart disease (CHD) and atrial fibrillation (AF) are the two major cardiovascular diseases with the highest disability and mortality rate in both Chinese and western countries. AF is a risk factor as well as a consequence of acute coronary syndromes (ACS), with one in five patients developing AF within 5 years post ACS. 1 Coronary artery disease affects about 30% of AF patients, and about 10% of all AF patients who have percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). 1 PCI is one of the main methods for ACS. Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) combined with aspirin and clopidogrel is the key to prevent stent thrombosis after PCI. Atrial fibrillation relies on oral anticoagulant drugs (OACs) to reduce thromboembolism events such as stroke. The difficulty of anticoagulant therapy for CHD complicated with AF is that these two kinds of drugs can not be completely replaced, and the combination of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs also faces the risk of increased bleeding. 2 How to achieve the maximum benefit and minimize the risk of bleeding is the pivotal to develop anticoagulant therapy for CHD patients complicated with atrial fibrillation.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend that patients with AF could receive short-term OAC plus DAPT triple therapy after PCI, followed by OAC plus clopidogrel, which can be maintained only with OAC for life after 1 year. 3 The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines for antithrombotic therapy 4 and the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for the management of patients with AF 5 recommend risk stratification according to CHADS2 or CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Patients with scores ≥ 2 are recommended by ESC guidelines, and patients with scores between 0 to 1 are recommended to receive DAPT for 1 year after operation. At present, although the guidelines make recommendations for the treatment of ACS patients complicated with AF, most of the evidence-based guidelines were from Caucasians. However, the proportion of prescribing anticoagulants for AF patients in China has been low. The GLORIA-AF study 6 suggested that compared with the 63.9% usage rate of warfarin in Europe, the usage rate of warfarin in China is only 20.3%, and the proportion of using anticoagulants may be even lower in patients with ACS and AF. Warfarin, as a traditional anticoagulant, should only be prescribed when the coagulation related indexes are monitored, and its dosage needs to be adjusted routinely. It interacts with a variety of drugs and even foods, which limits its wide clinical application. At present, the novel oral anticoagulants (NOAC) have the advantages of rapid effect, predictable efficacy, no need for routine blood coagulation monitoring, and routine dose adjustment. Among the NOACs, rivaroxaban, a direct inhibitor of the Xa factor, has been approved to prevent stroke and systemic embolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients in China. The PIONEER-AF PCI study 7 is an open-label, randomized, controlled, multicenter study to characterize two strategies for the treatment of PCI patients prescribed with rivaroxaban and warfarin. The results (TIMI, composite endpoints for major and minor bleeding requiring treatment) showed that the two rivaroxaban groups were significantly better than those in the warfarin group. All-cause mortality and hospitalization were reduced in the rivaroxaban group. The PIONEER-AF PCI study suggested that rivaroxaban could replace warfarin, and be used together with clopidogrel as an anticoagulation therapy after PCI in patients with AF.

However, at present, there is no large-scale study focusing on the efficacy and safety of the NOAC, rivaroxaban, combined with clopidogrel in PCI patients with ACS complicated with AF. Therefore, the current study explored the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban combined with clopidogrel as an anticoagulation therapy after PCI in Chinese ACS patients complicated with AF.

Methods

Study Population

A total of 100 patients with ACS with NVAF who underwent PCI in our hospital from January 2018 to September 2018 were selected. This study was conducted at The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University, and was approved by the Ethical Committee of our institution (2018R098). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Selection criteria:

NVAF was diagnosed by echocardiography and electrocardiogram;

Anticoagulant therapy was needed according to CHADS2-VASC score;

Drug-eluting stent (DES) was implanted.

Exclusion criteria:

-

d.

Severe hepatic and renal dysfunction (CrCl < 30ml /min);

-

e.

Clinically significant active bleeding or diseases with an evident risk of massive hemorrhage;

-

f.

Combined use of cyclosporine, systemic ketoconazole, itraconazole, tacrolimus and dronedarone;

-

g.

With contraindications of antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants;

-

h.

Allergic to drugs;

-

i.

Poor compliance, and the observation indexes such as INR cannot be followed up regularly according to the doctor's order.

Study Treatment

The patients were randomly divided into two groups. The trial group (rivaroxaban group) was treated with rivaroxaban and clopidogrel, following the daily treatment regimen with 15 mg rivaroxaban and 75 mg clopidogrel (orally) for one year after PCI. The control group (warfarin group) received triple therapy of warfarin, clopidogrel and aspirin. The regimen was to take warfarin orally primarily with an initial dose of around 1 to 3 mg, which was later adjusted according to the results of monitoring the international standardized ratio (INR), and the target range of INR should be 2.0 to 3.0 in 2 to 4 weeks. It was monitored afterward according to the guidelines. At the same time, 100 mg aspirin (discontinued after 6 months) and 75 mg clopidogrel were prescribed orally once a day; warfarin and clopidogrel were discontinued after one year.

Follow-up

All patients were followed up for 12 months, and the follow-up was carried out by telephone or outpatient reexamination. All patients underwent routine reexamination of liver and kidney function, blood routine, electrocardiogram and cardiac ultrasound. Close observation and attention were made on any suggested signs of systemic, brain or pulmonary embolism, or any adverse bleeding events and signs. The risk of bleeding was evaluated according to the HAS-BLED score, and whether to strengthen the follow-up and observation was decided according to the score.

Primary Efficacy Endpoint

The primary efficacy endpoint events were the main adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) within 12 months, including all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), stent thrombus (ST), unplanned revascularization (PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting) and stroke. Stroke was defined as a focal neurological defect that lasted for more than 24 h and may result in a vascular event that required hospitalization or death.

Secondary Safety Endpoint

The secondary safety endpoint events were TIMI major and minor bleeding in 12 months, and the diagnostic criteria of TIMI were severe hemorrhage, including hemorrhagic stroke (confirmed by computed tomography or head magnetic resonance imaging) or clinically evident hemorrhagic signs with decreased hemoglobin level ≥ 5g/ dL. If there was no apparent bleeding site, and the hemoglobin level was reduced by 5g / dL or ≥ 4g / dL, then it was considered to be TIMI minor bleeding. 8

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis software SPSS 19.0 was used, the measurement data were expressed by mean ± standard deviation (SD), the normality and homogeneity of variance of each group of data were tested respectively. If the data were in accordance with normal distribution, the independent sample t-test would be used to compare the two groups of data; otherwise, the non-parametric test would be used for data analysis. The percentage of counting data was used to indicate that the overall rates of MACEE events and bleeding events in different groups were compared by chi-square test. COX survival analysis was used to compare the risk of MACEE events and bleeding events in different groups, and Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to complete the cumulative risk rate curve. When P < 0.05, it was considered that the difference is statistically significant.

Results

General Characteristics

In this study, a total of 100 cases were enrolled, including 63 men and 37 women. The age ranged from 37 to 77 years old, with the median age of 58 years old. There were 51 cases in the warfarin group and 49 cases in the rivaroxaban group (Figure 1). There was no difference in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, heart failure stroke between the two groups. Most of the clinical baseline in two groups showed no significant difference, including CHADS2-VASC score and HAS-BLED score (Table 1)

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

The Demographic and Clinical Indicators in Different Groups.

| Parameter | Total (n = 100) | Group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin Group (n = 51) | Rivaroxaban Group (n = 49) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 63 (63.00) | 31 (60.80) | 32 (65.30) | 0.640 |

| Female | 37 (37.00) | 20 (39.20) | 17 (34.70) | |

| Age | 58.00 (50.00-65.00) | 60.00 (50.00-66.00) | 57.00 (50.00-63.00) | 0.207 |

| BMI | 24.93 ± 3.16 | 24.84 ± 3.26 | 25.03 ± 3.09 | 0.767 |

| BMI | ||||

| <18.5 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.977 |

| [18.5 to 24) | 46.00 (46.00) | 24 (47.10) | 22 (44.90) | |

| [24 to 28) | 36 (36.00) | 18 (35.30) | 18 (36.70) | |

| ≥28 | 18 (18.00) | 9 (17.60) | 9 (18.40) | |

| Smoking | 38 (38.00) | 24 (47.1) | 14 (28.60) | 0.057 |

| Drinking | 50 (50.00) | 23 (45.10) | 27 (55.10) | 0.317 |

| Hypertension | 71 (71.00) | 40 (78.40) | 31 (63.30) | 0.095 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 30 (30.00) | 11 (21.60) | 19 (38.80) | 0.061 |

| Heart Failure | 20 (20.00) | 12 (23.50) | 8 (16.30) | 0.368 |

| Stroke | 6 (6.00) | 3 (5.90) | 3 (6.10) | 1.00 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 82.65 (78.60-89.25) | 85.00 (78.75-89.00) | 81.20 (78.40-89.40) | 0.418 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 61.52 (58.95-63.04) | 61.57 (58.57-62.99) | 61.47 (60.00-63.00) | 0.825 |

| Left Atrial Size (mm) | 36.00 (32.00-43.00) | 36.00 (32.00-43.00) | 33.00 (32.00-43.00) | 0.430 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 140.70 ± 12.22 | 140.49 ± 14.15 | 140.92 ± 9.97 | 0.861 |

| History of Bleeding Disorders | 5 (5.00) | 3 (5.90) | 2 (4.10) | 1.00 |

| CHADS2-VASC Score | 3.00 (2.00-4.00) | 3.00 (2.00-4.00) | 3.00 (2.00-3.00) | 0.243 |

| HAS-BLED Score | 2.00 (2.00-3.00) | 3.00 (2.00-3.00) | 2.00 (2.00-3.00) | 0.087 |

Primary Outcome Endpoint Event

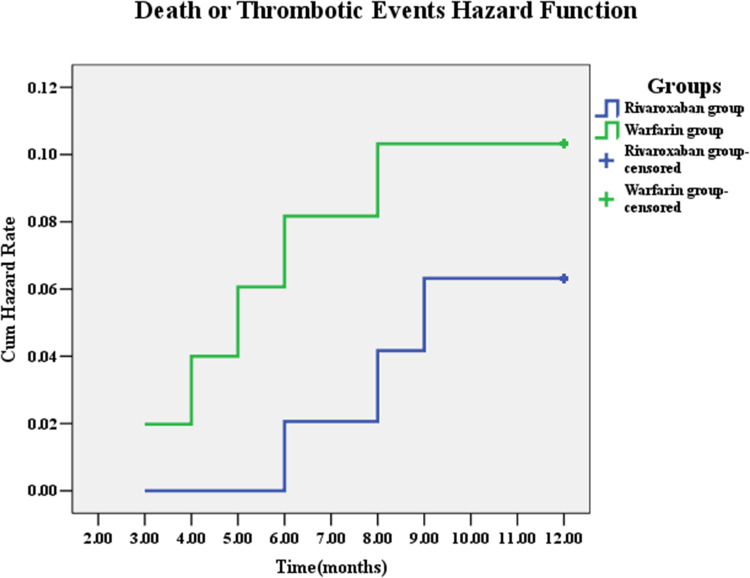

All patients were followed up for 12 months, and a total of 8 (8.00%) patients were found having MACEE events, including 3 (3.00%) of non-fatal myocardial infarction, 1 (1.00%) of unplanned revascularization, and 4 (4.00%) of stroke. No event of all-cause death or in-stent thrombosis occurred. The number of MACEE events in the warfarin group was 5 (9.80%), including 1 non-fatal myocardial infarction (2.00%), 1 unplanned revascularization (2.00%), 3 stroke (5.90%). The number of MACEE events in the rivaroxaban group was 3 (6.10%), including 2 non-fatal myocardial infarction (4.10%) and 1 stroke (2.00%). Although MACEE events in the rivaroxaban group was less than that in the warfarin group, the risk of MACEE events in the two groups was not statistically significant. (Table 2, Figure 2)

Table 2.

The Thrombotic Events and Bleeding Events in Different Groups.

| Events | Warfarin | Rivaroxaban | Rivaroxaban VS Warfarin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | N(%) | Relative Risk (95% CI) | P | |

| Primary Outcome Endpoint Event | 5 (9.80) | 3 (6.10) | 0.60 (0.14-2.50) | 0.479 |

| Non-lethal MI | 1 (2.00) | 2 (4.10) | 1.97 (0.18-21.75) | 0.579 |

| All-cause Mortality | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | - | - |

| Unplanned Revascularization | 1 (2.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.00-144513.6) | 0.609 |

| Stroke | 3 (5.90) | 1 (2.00) | 0.34 (0.03-3.22) | 0.343 |

| Stent Thrombosis | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | - | - |

| Secondary Safety terminal events | 8 (15.70) | 1 (2.00) | 0.12 (0.02-0.97) | 0.047 |

| Severe Bleeding | 1 (2.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.00-150525.4) | 0.612 |

| Slight Bleeding | 7 (13.70) | 1 (2.00) | 0.14 (0.02-1.12) | 0.064 |

Figure 2.

Cumulative Hazard Rates for the primary outcome of death or thrombotic events according to different treatment group.

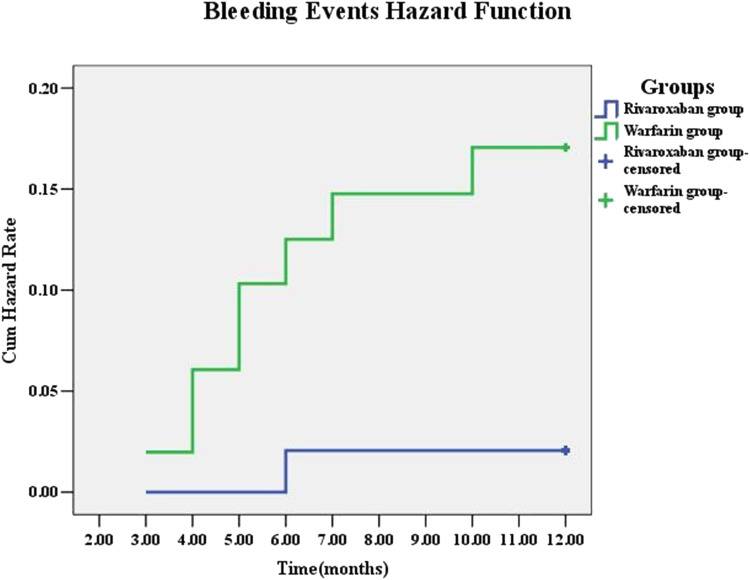

Secondary Safety Endpoint Events

All patients were followed up for 12 months, and 9 (9.00%) cases of them were found having bleeding events, including 1 with major bleeding and 8 patients with minor bleeding (Table 2). The number of bleeding events in warfarin group was 8 (15.7%), including one case (1.00%) with major bleeding, mainly manifested as cerebral hemorrhage. The number of bleeding events in the rivaroxaban group was 1 (2.00%), presented as minor bleeding. No major bleeding cases were found in the rivaroxaban group. In conclusion, the risk of bleeding in the warfarin group was significantly higher than that in the rivaroxaban group (P = 0.047, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cumulative Hazard Rates for the secondary outcome of bleeding events according to different treatment group.

We further analyzed the risk factors for bleeding events using COX regression analysis, and the results displayed that using warfarin was an independent risk factor for bleeding events (HR 8.22, 95% CI: 1.03-65.74, Table 3), no other risk factors were found.

Table 3.

COX Regression Analysis of the Predictors of Bleeding.

| Factors | Total | Femle | Male | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | |

| Warfarin VS Rivaroxaban | 8.22 | 1.03 to 65.74 | 0.047 | - | - | - | 6.71 | 0.81 to 55.76 | 0.078 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

AF is the most common arrhythmia and is the foremost independent risk factor for stroke and systemic embolism. The comorbidity of CAD and AF requires different anticoagulant combination treatment. The guidelines and the recent expert consensus report9,10 recommend the “triple therapy” (TT), which is a combination of OACs and DAPT to prevent thromboembolic events in patients with AF receiving PCI. The treatment option for these patients is particularly challenging due to a significantly increased risk of thromboembolic events, and a further increased risk of bleeding during active antithrombotic therapy.11,12

There are few studies on the efficacy and safety of oral anticoagulants combined with antiplatelet drugs after PCI. In this study, patients with ACS complicated with AF were followed up for 1 year after PCI. The results showed that the efficacy of the dual antithrombotic therapy, which comprises rivaroxaban and clopidogrel, was similar to the triple antithrombotic therapy, which consists of warfarin, aspirin and clopidogrel; however, the dual antithrombotic therapy using rivaroxaban and clopidogrel showed a better outcome in respect of the safety property. The safety was mainly evaluated by bleeding events, including TIMI major and minor bleeding. The results demonstrated that the total risk of major bleeding in the rivaroxaban group was 88% lower than that in the warfarin group. Since 2009, NOACs, including direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) dabigatran and direct factor Xa inhibitor apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban, have become an alternative of VKA because of their predictable and safe pharmacological characteristics. As an adjuvant to dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with ACS, NOAC may be associated with increased bleeding risk and moderate benefits. Daily intake of rivaroxaban (2.5 mg; twice a day) significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke. 13 For the treatment of VTE, NOACs have safer features and similar effects than vitamin K antagonist (VKA). 14 In thrombus prevention of AF, NOACs are associated with the most significant benefit by reducing ischemic events and hemorrhagic complications, and may reduce mortality compared with VKA. 15

Studies have shown that triple antithrombotic therapy increases the risk of bleeding events in patients undergoing PCI, and is an independent predictor of massive bleeding complications.16–18 Bencivenga, L et al. analyzed recent literature, 19 proposing that triple therapy was the short-term treatment for AF patients who underwent PCI. In contrast, dual therapy (antiplatelet plus OAC) may be the first choice for patients with a high risk of bleeding. Gibson, CM et al. 20 studied the safety and efficacy of drug therapy in NVAF patients after PCI. The results revealed that the three groups had similar efficacy rates: low-dose rivaroxaban (15 mg once daily) plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months (group 1), very-low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months (group 2), and standard therapy with a dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonist (once daily) plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months (group 3). The safety of this study was mainly evaluated by bleeding events, including TIMI major and minor bleeding. The results showed that the total risk of major bleeding events in rivaroxaban group was 88% lower than that in the warfarin group. This was similar to the results from the above study. At the same time, studies also showed that among patients with AF who received intracoronary stent implantation, they had a lower risk of all-cause mortality or adverse events hospitalization when taking daily rivaroxaban 15 mg plus P2Y12 inhibitor, or daily 2.5 mg rivaroxaban plus DAPT, than taking VKA plus DAPT. Of note, all-cause mortality was mainly caused by bleeding events. The primary outcome of adverse events mainly includes death or rehospitalization due to cardiovascular causes. 21 The results of WOEST trial 22 indicated that for ACS patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, on the basis of oral anticoagulants and antiplatelet therapy, clopidogrel alone without aspirin could significantly reduce bleeding complications, and did not increase the incidence of thrombotic events. This study established the efficacy and safety feasibility of clinical grouping of oral anticoagulants and P2Y12 inhibitors. Moreover, Kerneis, M et al. 23 analyzed the PIONEER AF-PCI and found that rivaroxaban therapy was superior to warfarin plus antiplatelet therapy in patients with AF who received PCI.

Studies have also shown that rivaroxaban based antithrombotic regimens can reduce total bleeding events, including events other than the first event in patients with AF who receive antiplatelet therapy after PCI.24,25 Brunetti, ND et al. performed a meta-analysis that included patients with NVAF treated with PCI and assessed all bleeding risks 26 : compared with patients receiving the three groups of standard treatment, patients who received rivaroxaban or dabigatran had a significantly lower risk of bleeding. The above results are consistent with the results of our study. It is noteworthy that a study showed that bleeding time was significantly prolonged by the combination of rivaroxaban and clopidogrel in approximately one-third of subjects, however, they found enhanced efficacy of rivaroxaban and clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome. 27 On the other hand, studies have confirmed that dual antithrombotic therapy is superior to triple antithrombotic therapy in terms of efficacy and safety. Chi, G et al. analyzed the safety and efficacy of non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants in patients with AF after PCI through bivariate analysis. 28 The results showed that a treatment regimen based on rivaroxaban or dabigatran was superior to VKA plus dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with AF who received PCI. To sum up, for patients with NVAF receiving antithrombotic therapy after PCI, our practice should be adjusted and shifted to the dual treatment of OACs and clopidogrel in most patients. 29

At present, there are very few studies focusing on antithrombotic therapy after PCI for AF patients with ACS in the Chinese population. In order to remedy this limitation, antithrombotic therapy for AF patients with ACS after PCI was studied. Our study provides a better choice for ACS patients with atrial fibrillation after PCI. Rivaroxaban plus clopidogrel dual therapy may replace warfarin combined DAPT, which can achieve better therapeutic effect and reduce the occurrence of bleeding and other adverse events, so as to better improve the prognosis and quality of life after PCI. However, there are still some limitations and deficiencies in this study. First of all, this study is a single-center, small-sample study; there may be a certain regional population bias. In the future, we will further carry out multicenter, large-sample randomized controlled trials. Secondly, the follow-up time of this study was relatively short. The latent complications of the two treatments may be omitted, and we will conduct a long-term follow-up of this population to determine the long-range effects. In addition, the duration of triple therapy in this study was 6 months which was not carried out according to the risk of thromboembolism and bleeding, we will improve the study design in further research. Finally, due to the wide confidence interval for the results of the dual treatment in thrombotic events and bleeding events, we will investigate this further in the future.

Conclusion

For Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome complicated with atrial fibrillation after PCI, the dual antiplatelet therapy using the oral anticoagulants rivaroxaban and clopidogrel has an equivalent effect as traditional triple therapy using warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel, with potentially lower bleeding events. This may provide evidence for the application of rivaroxaban and clopidogrel for post-PCI patients with atrial fibrillation combined with coronary heart disease in China.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the patients who participated in this study, as well as to the physicians and nurses in the for their assistance in this study.

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- DAPT

dual antiplatelet therapy

- DAT

double antithrombotic therapy

- DOAC

direct oral anticoagulant

- OAC

oral anticoagulation

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- SAPT

single antiplatelet therapy

- TAT

triple antithrombotic therapy

- VKA

vitamin K antagonist.

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Material: The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' Contributions: BL and YXH have made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study. ZYQ was involved in acquisition of data, data entry and data cleaning. CXR and FLZ were involved in analysis and interpretation of data. BL and YXH have been involved in drafting the manuscript. ZJD was involved in revising manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed substantially to its revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: This study was conducted at The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University, and was approved by the Ethical Committee of our institution (2018R098). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the China Youth Clinical Research Fund-VG Fund (grant number No. 303-09-02-62).

ORCID iD: Ji-dong Zhang https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1957-8526

References

- 1.Kralev S, Schneider K, Lang S, Süselbeck T, Borggrefe M. Incidence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing first-time coronary angiography. Plos one. 2011;6(9):e24964. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schömig A, Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, et al. A randomized comparison of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy after the placement of coronary-artery stents. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(17):1084–1089. Doi: 10.1056/nejm199604253341702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lip GY. Recommendations for thromboprophylaxis in the 2012 focused update of the esc guidelines on atrial fibrillation: a commentary. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : jth. 2013;11(4):615–626. Doi: 10.1111/jth.12140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pruthi RK. Review of the American college of chest physicians 2012 guidelines for anticoagulation therapy and prevention of thrombosis. Semin Hematol. 2013;50(3):251–258. Doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 Aha/acc/hrs guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071–2104. Doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huisman MV, Lip GY, Diener HC, et al. Design and rationale of global registry on long-term oral antithrombotic treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation: a global registry program on long-term oral antithrombotic treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2014;167(3):329–334. Doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, et al. An open-label, randomized, controlled, multicenter study exploring two treatment strategies of rivaroxaban and a dose-adjusted oral vitamin k antagonist treatment strategy in subjects with atrial fibrillation who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (pioneer af-pci). Am Heart J. 2015;169(4):472–478.e475. Doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R, et al. Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (timi) trial, phase i: a comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation. 1987;76(1):142–154. Doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 Aha/acc/hrs guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):e1–76. Doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.gy l, s w, k h, et al. Management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary or valve interventions: a joint consensus document of the european society of cardiology working group on thrombosis, european heart rhythm association (ehra), european association of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions (eapci) and european association of acute cardiac care (acca) endorsed by the heart rhythm society (hrs) and Asia-pacific heart rhythm society (aphrs). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(45):3155–3179. Doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Walraven C, Hart RG, Connolly S, et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: the atrial fibrillation investigators. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1410–1416. Doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.108.526988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Secemsky EA, Butala NM, Kartoun U, et al. Use of chronic oral anticoagulation and associated outcomes among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(10):10. Doi: 10.1161/jaha.116.004310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weitz JI. Insights into the role of thrombin in the pathogenesis of recurrent ischaemia after acute coronary syndrome. Thromb Haemostasis. 2014;112(5):924–931. Doi: 10.1160/th14-03-0265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baber U, Mastoris I, Mehran R. Balancing ischaemia and bleeding risks with novel oral anticoagulants. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(12):693–703. Doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grajek S, Olasińska-Wiśniewska A, Michalak M, Ritter SS. Triple versus double antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and stent implantation: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Kardiol Pol. 2019;77(9):837–845. Doi: 10.33963/kp.14899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon CP, Gropper S, Bhatt DL, et al. Design and rationale of the re-dual pci trial: a prospective, randomized, phase 3b study comparing the safety and efficacy of dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran etexilate versus warfarin triple therapy in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(10):555–564. Doi: 10.1002/clc.22572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopes RD, Rao M, Simon DN, et al. Triple versus dual antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2016;129(6):592–599.e591. Doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naruse Y, Sato A, Hoshi T, et al. Triple antithrombotic therapy is the independent predictor for the occurrence of major bleeding complications: analysis of percent time in therapeutic range. Circulation. Cardiovascular interventions. 2013;6(4):444–451. Doi: 10.1161/circinterventions.113.000179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bencivenga L, Komici K, Corbi G, et al. The management of combined antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a particularly complex challenge, especially in the elderly. Front Physiol. 2018;9:876. Doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, et al. Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing pci. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(25):2423–2434. Doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1611594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson CM, Pinto DS, Chi G, et al. Recurrent hospitalization among patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing intracoronary stenting treated with 2 treatment strategies of rivaroxaban or a dose-adjusted oral vitamin k antagonist treatment strategy. Circulation. 2017;135(4):323–333. Doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.116.025783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9872):1107–1115. Doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62177-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerneis M, Yee MK, Mehran R, et al. Association of international normalized ratio stability and bleeding outcomes among atrial fibrillation patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. Cardiovascular interventions. 2019;12(2):e007124. Doi: 10.1161/circinterventions.118.007124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chi G, Yee MK, Kalayci A, et al. Total bleeding with rivaroxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;46(3):346–350. Doi: 10.1007/s11239-018-1703-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastiany A, Matteau A, El-Turaby F, et al. Comparison of systematic ticagrelor-based dual antiplatelet therapy to selective triple antithrombotic therapy for left ventricle dysfunction following anterior stemi. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10326. Doi: 10.1007/s11239-018-1703-5x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunetti ND, Tarantino N, De Gennaro L, Correale M, Santoro F, Di Biase M. Direct oral anticoagulants versus standard triple therapy in atrial fibrillation and pci: meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2018;5(2):e000785. Doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubitza D, Becka M, Mück W, Schwers S. Effect of co-administration of rivaroxaban and clopidogrel on bleeding time, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics: a phase i study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2012;5(3):279–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chi G, Kerneis M, Kalayci A, et al. Safety and efficacy of non-vitamin k oral anticoagulant for atrial fibrillation patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a bivariate analysis of the pioneer af-pci and re-dual pci trial. Am Heart J. 2018;203:17–24. Doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duerschmied D, Brachmann J, Darius H, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: should we change our practice after the pioneer af-pci and re-dual pci trials? Clinical research in cardiology : official journal of the german cardiac society. 2018;107(7):533–538. Doi: 10.1007/s00392-018-1242-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]