Abstract

Aim

Advancements in telemonitoring (TM) for patients with heart failure (HF) are incongruous because of the effect of TM intervention and various types of TM. This study aimed to clarify patients’ experiences in using the TM tool.

Methods

This was a qualitative study. Data were evaluated using qualitative content analysis. Nine patients with heart failure → HF participated and completed the 1-month study period.

Results

The experience of this TM tool was determined using semi-structured interviews followed by qualitative content analysis. Finally, five themes emerged: habituation of self-care behaviour, no burden for use, a feeling of security, additional functions and advice rather than guidance.

Conclusion

This TM tool is easy to use and has the potential to promote self-management in patients with HF. Based on the aforementioned findings, we revised this tool and added some functions and will perform additional tests.

Keywords: heart failure, telemonitoring, patient perspective, self-management, qualitative study

Introduction

Heart disease remains the second-leading cause of death in Japan, with 36% of patients with heart disease ultimately suffering death from heart failure (HF), It is mainly a lifestyle-related disease and is the leading cause of hospitalisation worldwide (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2019; Ponikowski et al., 2016; Tsutsui et al., 2019). Toback et al., proposed that improved self-management would increase adherence, promote patient quality of life (QOL), advance clinical outcomes, reduce hospital re-admissions and decrease hospitalisation costs (Toback & Clark, 2017). Self-management interventions for chronic diseases during home care are effective in decreasing patient-borne costs, cost of health care and number of outpatient and emergency room visits, reducing hospital stays and improving health-related QOL. (Kamei, 2013) Recent studies have shown that non-invasive telemonitoring (TM) interventions reduced HF-related hospitalisation and trends in total mortality and HF-related admissions (Carbo et al., 2018; Kotooka et al., 2018). Moreover, these interventions also promoted improvements in health-related QOL, as well as and HF knowledge and self-care behaviours (Inglis et al., 2015).

Previous studies exploring patients’ perceptions on non-invasive TM had concluded that this approach promoted patients’ engagement in their own care and increased self-care activities (Fairbrother et al., 2014; Lyngå et al., 2013). However, many studies on TM observed signs of exacerbation determined from biometric information, such as blood pressure and weight. Moreover, we assumed that monitoring subjective symptoms aside from body weight and blood pressure would help detect early signs of exacerbation, promote early intervention to prevent exacerbation and readmission and improve self-management in patients with HF.

Patients with HF receive vague or insufficient instructions, display inconsistent behaviours and symptoms, are affected by socioeconomic factors, have poor adherence, and have physical and psychosocial restrictions due to HF and poor psychological response to restrictions from medical professionals, all of which lead to worsening of symptoms (Sevilla-Cazes et al., 2018). A study that surveyed the knowledge of community nurses revealed that they had basic understanding of HF but scored poorly on weight assessment, blood pressure management. (Fowler, 2012)

As such, we developed a non-invasive TM tool for patients with HF that aimed to improve self-management by providing a system that allows the sharing of patient data among a patient with HF, clinicians, nurses and physical therapists. The current study therefore clarifies users’ experiences and revise the tool based on data obtained from the viewpoints of patients with HF. This study aimed to clarify the patients’ perspectives in using the non-invasive TM tool and consider the potential applications for the nursing practise. We intend to obtain user feedback regarding the design of the tool to improve functionality and acceptability in the final product before it is tested in a larger sample. We believe that clarifying these aspects is meaningful in promoting self-management of patients with HF.

Prototype Development

In this study, non-invasive TM was defined as the remote, Internet-based monitoring of patients with HF on weight, blood pressure, heart rate and signs and symptoms that disclose the actual condition of the patient with HF.

We developed the non-invasive TM tool following the 2017 Japanese evidence-based guideline of acute and chronic HF (Tsutsui et al., 2019). The daily data entered by the patients with HF included weight, blood pressure, pulse rate, shortness of breath, dyspnoea on exertion, urine volume, lower limb swelling, nocturnal urine volume and bowel movement. Figure 1 shows screenshots of one of the input screens.

Figure 1.

Screenshots of examples of home screens and recording screen.

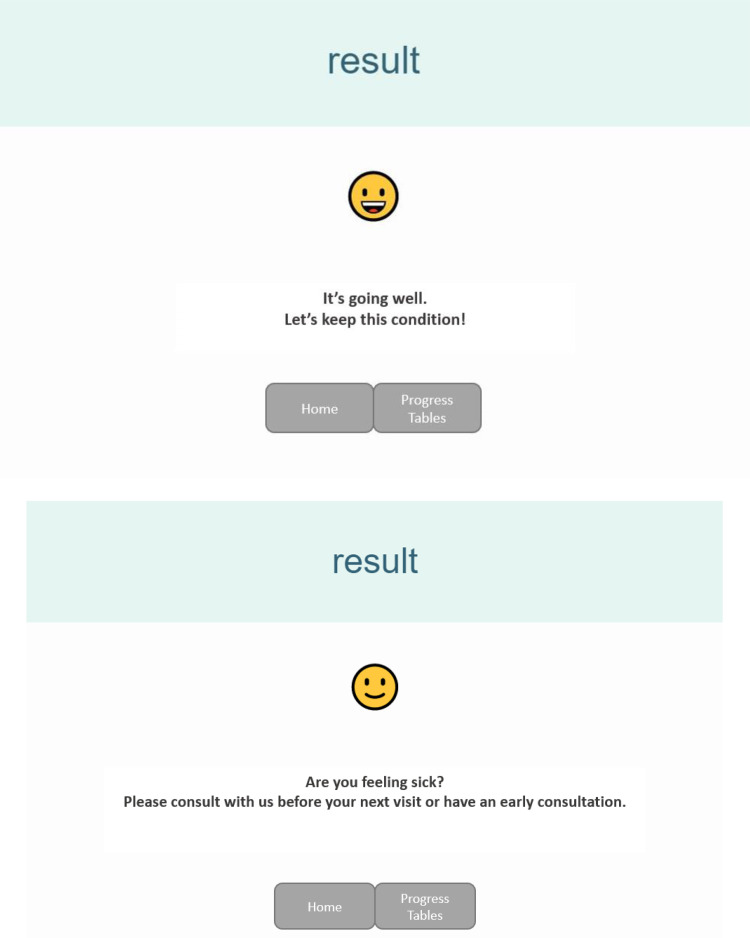

The entered data were scored and sent as a comment for consultation so that patients with HF could act promptly when signs of exacerbation occurred. The score was calculated by adding points when weight, swelling or shortness of breath increased or when urine volume decreased, with a higher score indicating increased likelihood for worsening HF and high degree of urgency. Thereafter, a comment and emoticon were displayed according to the score. Four types of comments were provided, each depending on the score, e.g. ‘Please consult with us before your next visit or have an early consultation.’ or ‘It's going well.’ Figure 2 shows screenshots of examples of feedback comments and emoticons. It stands for an ‘emotion icon’ and shows facial expression using characters to express a character's feelings, mood or reaction.

Figure 2.

Screenshots of examples of feedback comments and emoticons.

Using the Tool

This tool was cloud-based. Patients with HF access the dedicated website and enter their daily data once daily using the Internet-connected tablet device (we lent the device to the participants). Healthcare providers, such as physicians, nurses and physical therapists, could see the graph and table via the dedicated website. Thus, they can assess the patient's condition without in-person visit and contact the patient if there were signs or symptoms.

Figure 3 shows screenshots of examples of graph and table.

Figure 3.

Screenshots of examples of graph and table.

Methods

Setting and Participants

Eligible participants were recruited from one Japanese academic medical centre with cardiovascular outpatient clinic services. HF in this study corresponds to I50 in ICD-10. After obtaining consent, participants were instructed by the researcher regarding the use of the non-invasive TM tool.

A total of 10 participants were planned to be recruited for this qualitative study. Patients who had a clinical diagnosis of HF, were able to speak Japanese, were able to operate mobile devices or laptop computers, and were willing to provide informed consent were eligible to participate in this study. We used convenience sampling for recruitment, and patients were recruited by their direct care team during scheduled clinic visits.

Data Collection and Analysis

This study aimed to understand patient's perspectives and provide design considerations for a TM tool that could effectively support patients with HF. We observed participants use of the tool on a daily basis during the study period. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to elicit participants’ feedback on the tool design and behavioural changes related to self-management, which included information regarding what was and was not helpful and suggestions for improvement.

After participation for 1 month, the authors conducted individual semi-structured interviews. Face-to-face interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Participants underwent an approximately 30- to 60-min poststudy interview. The frequency of use was determined from the server where the data were stored. We performed data analysis using qualitative content analysis following the steps outlined by Graneheim to identify emerging themes directly from patients’ thoughts and experience (Graneheim et al., 2017).

This manuscript adheres to the standards for reporting qualitative studies (Dossett et al., 2021).

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Chiba University Graduate School of Nursing. The consent form provided information regarding the aim, procedures and potential risks and benefits to each eligible patient in person.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of nine patients with HF participated in this study. One additional patient with HF was invited to participate in this study but refused because of other commitments. All participants had a mean age of 62.6 years (Table 1), with three having no experience with tablet devices or computers. Table 1 summarises the participants’ characteristics. During the study, the average usage rate per month was 92.1%, which indicated that they used it daily during the one-month study period.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n = 9).

| ID | Gender | Age (years) | Size of household | NYHA | LVEF (%) | Having experiences with Tablet device |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | F | 65 | 3 | II | 29.4 | Yes |

| B | M | 72 | 2 | III | 42.0 | Yes |

| C | M | 80 | 2 | III | 40.0 | No |

| D | F | 76 | 4 | III | 45.0 | No |

| E | M | 68 | 2 | IV | 28.2 | Yes |

| F | M | 45 | 2 | II | 34.4 | Yes |

| G | M | 52 | 2 | II | 52.8 | Yes |

| H | M | 37 | 2 | II | 35.0 | Yes |

| I | M | 68 | 4 | III | 27.8 | No |

NYHA, New York Heart Association. LVEF, Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction.

Qualitative Findings

As a result of qualitative analysis, the following five themes emerged: habituation of self-care behaviour, no burden for use, a feeling of security, additional functions and advice rather than instructions.

Habituation of Self-Care Behaviour

Most participants stated that self-care behaviours, such as weight monitoring and using the tool, became part of a routine daily life. Some nurses check the data daily, while others just check before contacting. At any rate, participants felt being monitored in a positive way because nurses were able to check patient's data and told that they were referring to it.

It's good to be able to input data consciously, when done every day. (A)

The nurse said she sees this data and uses it as a reference. It seems like I’m being monitored in a good way, so I have to input my data every day. (G)

No Burden for Use

No participant experienced any difficulties in using the tool and tablet devices, suggesting that the tool was easy to use. Furthermore, even participants who had never operated a tablet device showed no difficulty in using it. Most participants took only a few minutes to enter their data.

It's not hard to type every day. (G)

It was easy to operate, so it was not particularly difficult. (H)

A Feeling of Security

Some nurses checked the data daily and told the participant about it. Participants entered their data daily with or without symptoms. Moreover, they received a message from the tool upon entering the data daily. Considering that health care providers can check the patient's data anytime, participants felt secure with the thought that nurses were managing their physical condition by looking at the data such as blood pressure, swelling and weight. Moreover, some participants were relieved to see positive feedback.

The nurse always tells me that she's observing me, so I feel safe. (B)

I feel secure knowing that people at the hospital are observing my condition through this tool. (D)

The nurses are aware of my condition and they are helpful. This is important. (I)

Additional Functions

Almost all participants suggested that additional functions for interaction can promote communication with health care providers. Moreover, they needed a bulletin board that can be freely written, such as the amount of activity during the day, dietary content, fatigue and additional oral administration of diuretics. Some participants also recorded their daily living conditions and attempted to link them with changes in weight and symptoms.

I think it would be nice to be able to leave special notes. For example, if I go shopping or to a spa, I sometimes wonder what I ate and how that relates to my weight gain or loss. (C)

In terms of sharing information, it would be nice if there was some sort of remarks section into which we could both make entries. I’d like to keep track of what I was and was not able to do with the advice I received. (E)

Advice Rather Than Guidance

This theme reflects a negative aspect with the use of the tool. This tool has a system that provides emoticons and comments to evoke a consultation behaviour when signs of HF exacerbation, such as weight gain or decreased urine volume, were observed. For example, ‘Are you feeling sick?

Please consult with us before your next visit or have an early consultation.’ However, participants did not refer to such message and, in some instances, expressed discomfort. They stated that they needed the advice about health or life rather than the consultation behaviours.

The comments suggest that I should see a doctor, but I don't care to because I don't feel strange. (B)

Rather than encouraging me to see a doctor, it would be better if you gave me advice on how to improve my specific heart condition. It would be annoying for the nurses and others if I called them every time, wouldn't it? (E)

A face that conveys pain is not very desirable because it makes one anxious. (F)

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore patients’ perspectives in using the non-invasive TM tool. Our results have indeed clarified the positive and negative aspects through which the tool will be revised.

Lyngå et al. (Lyngå et al., 2013) showed that self-care behaviours have increased and become habitual since the start of remote monitoring. Throughout this study, the average daily usage rate remained >90%, and self-management of one's weight or blood pressure and observation of HF symptoms became a habit. Moreover, almost all participants stated that the tool was easy to use. As such, this tool has the potential to be incorporated into clinical practise from the viewpoint of usability. Cajita et al., explored barriers to m-Health adoption, including lack of knowledge regarding the use of m-Health, decreased sensory perception, lack of need for technology, poorly designed interface and technological costs. Accordingly, their results showed that older adults tended to be hesitant when using mobile technology (Cajita et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2019). Our study also included elderly individuals who had never used tablets previously. Nonetheless, we were able to overcome the barriers described in previous studies by employing a very simple user interface.

A previous study has shown that more frequent monitoring increased patients’ sense of safety when they functioned independently at home, which allowed them to become less fearful of solitude, particularly if they lived alone (Walker et al., 2019). Our study showed similar results, indicating that incorporating a system that allows the medical staff to remotely monitor patient information is meaningful. We suggested that, when appropriate, nurses tell the patient that they look at the patients’ data via the internet. In addition, nurses can check the patients’ data prior to giving an instruction or seeing the patient at a visit. Therefore, nurses can focus on their assessments in advance, which may lead to efficient nursing practises.

A previous study suggested adding a bulletin board to share information related to HF experiences and discuss technical issues (Alnosayan et al., 2017). This suggestion was also described herein under additional functions, with some of our participants describing the need to include a bulletin board. In particular, taking temporary diuretics, going shopping and daily activities were not included in this tool. These are important matters for desirable self-management, in addition to changes in weight, vital signs, swelling and shortness of breath, considering that they help determine how daily activities affect weight, vital signs and HF symptoms. Moreover, nurses refer to and grasp the patients’ lifestyle; they can then give concrete advice about lifestyle modification and self-management.

This tool provided four types of comments as a guide for consultation, one positive comment and emoticon. Participants expressed positive feedback on the positive comment and smiley emoticon, but did not refer to any other comments given that they felt no change in their HF symptoms and hesitated to contact their healthcare professionals frequently according to the comments. In this study, negative emoticons only seemed to increase anxiety. Supportive environments from nurses or physicians facilitated self-care, reducing anxiety, motivation and adherence to treatment (Siabani et al., 2013). Therefore, comments and emoticons in this tool need to be modified to provide advice about symptom management or lifestyle rather than guidance for consultation.

Based on the obtained results, we have added a bulletin board and the modified comments and emoticons to encourage daily utilisation by patients with HF and nurses. The bulletin board can be used by both the patients and healthcare team. It enables an interactive non-face-to-face communication or consultation.

Conclusions/Importance to Nursing Profession

This study described patient perspectives in using the non-invasive TM tool for patients with HF, and five themes emerged. The nine participants in this study were very engaged with the tool and gave positive feedback about use including suggestions for improvement. Patients included herein articulated the need for additional functions of interaction with healthcare providers, positive feedbacks and a bulletin board to change their lifestyle and communicate with healthcare providers. Based on the aforementioned findings, we revised the tool and added some functions and will do additional testing of the non-invasive TM tool. In clinical settings, nurses need to have the supportive attitudes and give a sense of security. When contacting patients, nurses need to observe changes in the patient's symptoms and understand their lives.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the patients who participated in the study. This manuscript was derived from the primary author's doctoral thesis at the Graduate School of Nursing, Chiba University. The authors would like to thank editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language review.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Pfizer health research foundation. The study was supported by a grant from the Daiwa Securities Health Foundation.

ORCID iD: Motohiro Sano https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7608-9695

References

- Alnosayan N., Chatterjee S., Alluhaidan A., Lee E., Houston Feenstra L. (2017). Design and usability of a heart failure mHealth system: A pilot study. JMIR Human Factors, 4(1), e9. 10.2196/humanfactors.6481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajita M. I., Hodgson N. A., Lam K. W., Yoo S., Han H. R. (2018). Facilitators of and barriers to mHealth adoption in older adults With heart failure. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 36(8), 376–382. 10.1097/cin.0000000000000442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbo A., Gupta M., Tamariz L., Palacio A., Levis S., Nemeth Z., Dang S. (2018). Mobile technologies for managing heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemedicine Journal And E-Health: The Official Journal Of The American Telemedicine Association, 24(12), 958–968. 10.1089/tmj.2017.0269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossett L. A., Kaji A. H., Cochran A. (2021). SRQR And COREQ reporting guidelines for qualitative studies. JAMA Surgery, 156(9), 875–876. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother P., Ure J., Hanley J., McCloughan L., Denvir M., Sheikh A., McKinstry B. (2014). Telemonitoring for chronic heart failure: The views of patients and healthcare professionals - a qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(1–2), 132–144. 10.1111/jocn.12137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S. (2012). Improving community health nurses’ knowledge of heart failure education principles: A descriptive study. Home Healthcare Nurse, 30(2), 91–101. 10.1097/NHH.0b013e318242c5c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U. H., Lindgren B.-M., Lundman B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis S. C., Clark R. A., Dierckx R., Prieto-Merino D., Cleland J. G. (2015). Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10), 144–175. 10.1002/14651858.CD007228.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei T. (2013). Information and communication technology for home care in the future. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 10(2), 154–161. 10.1111/jjns.12039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotooka N., Kitakaze M., Nagashima K., Asaka M., Kinugasa Y., Nochioka K., Mizuno, A., Nagatomo, D., Mine, D., Yamada, Y., Kuratomi, A., Okada, N., Fujimatsu, D., Kuwahata, S., Toyoda, S., Hirotani, S., Komori, T., Eguchi, K., Kario, K., … Node, K. (2018). The first multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of home telemonitoring for Japanese patients with heart failure: Home telemonitoring study for patients with heart failure (HOMES-HF). Heart Vessels, 33(8), 866–876. 10.1007/s00380-018-1133-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyngå P., Fridlund B., Langius-Eklöf A., Bohm K. (2013). Perceptions of transmission of body weight and telemonitoring in patients with heart failure? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 8(1), 21524. 10.3402/qhw.v8i0.21524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2019, July 25). Demographic dynamics overview by cause of death . http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/geppo/nengai19/dl/kekka.pdf (in Japanese).

- Ponikowski P. Voors A. A. Anker S. D. Bueno H. Cleland J. G. Coats A. J. Falk V. González-Juanatey J. R. Harjola V. P. Jankowska E. A. Jessup M. Linde C. Nihoyannopoulos P. Parissis J. T. Pieske B. Riley J. P. Rosano G. M. Ruilope L. M. Ruschitzka F.… van der Meer P. (2016). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European Journal of Heart Failure, 37(27), 2129–2200. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla-Cazes J., Ahmad F. S., Bowles K. H., Jaskowiak A., Gallagher T., Goldberg L. R., Kangovi, S., Alexander, M., Riegel, B., Barg, F. K., & Kimmel, S. E. (2018). Heart failure home management challenges and reasons for readmission: A qualitative study to understand the patient’s perspective. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33, 1700–1707. 10.1007/s11606-018-4542-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siabani S., Leeder S. R., Davidson P. M. (2013). Barriers and facilitators to self-care in chronic heart failure: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Springerplus, 2, 320–320. 10.1186/2193-1801-2-320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toback M., Clark N. (2017). Strategies to improve self-management in heart failure patients. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession, 53(1), 105–120. 10.1080/10376178.2017.1290537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui H., Isobe M., Ito H., Okumura K., Ono M., Kitakaze M., Kinugawa, K., Kihara, Y., Goto, Y., Komuro, I., Saiki, Y., Saito, Y., Sakata, Y., Sato, N., Sawa, Y., Shiose, A., Shimizu, W., Shimokawa, H., Seino, Y., … On behalf of the Japanese Circulation Society and the Japanese Heart Failure Society Joint Working, G. (2019). JCS 2017/JHFS 2017 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure ― digest version ―. Circulation Journal, 83(10), 2084–2184. 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. C., Tong A., Howard K., Palmer S. C. (2019). Patient expectations and experiences of remote monitoring for chronic diseases: Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. International Journal Of Medical Informatics, 124, 78–85. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]