Abstract

Background:

Optimization of intentional weight loss in obese older adults, through preferential fat mass reduction, is challenging, as the concomitant lean mass loss may exacerbate sarcopenia. Recent studies have suggested within-day distribution of protein intake plays a role in determining body composition remodeling. Here, we assessed whether changes in within-day protein intake distribution are related to improvements in body composition in overweight/obese older adults during a hypocaloric and exercise intervention.

Methods:

Thirty-six community-dwelling, overweight-to-obese (BMI 28.0–39.9 kg/m2), sedentary older adults (aged 70.6±6.1 years) were randomized into either physical activity plus successful aging health education (PA+SA; n=15) or physical activity plus weight loss (PA+WL; n=21) programs. Body composition (by CT and DXA) and dietary intake (by three-day food records) were determined at baseline, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up visits. Within-day protein distribution was calculated as the coefficient of variation (CV) of protein ingested per defined time periods (breakfast [5:00–10:59], lunch [11:00–16:59] and dinner [17:00–1:00]). Secondary analysis was performed to determine associations between changes in protein intake distribution and body composition.

Results:

In both groups, baseline protein intake was skewed towards dinner (PA+SA: 49.1%; PA+WL: 54.1%). The pattern of protein intake changed towards a more even within-day distribution in PA+WL during the intervention period, but it remained unchanged in PA+SA. Transition towards a more even pattern of protein intake was independently associated with a greater decline in BMI (P<0.05) and abdominal subcutaneous fat (P<0.05) in PA+WL. However, changes in protein CV were not associated with changes in body weight in PA+SA.

Conclusion:

Our results show that mealtime distribution of protein intake throughout the day was associated with improved weight and fat loss under hypocaloric diet combined with physical activity. This finding provides a novel insight into the potential role of within-day protein intake on weight management in obese older people.

Keywords: Circadian timing of protein intake, weight, exercise, aging

1. INTRODUCTION

Obesity, i.e., body mass index (BMI) over ≥ 30 kg/m2, is a common health issue in older adults, affecting 35% of people aged ≥60 years (1, 2). Numerus health problems are associated with obesity in older adults including diabetes, cancer and osteoarthritis (3). Obesity related complications are a major source of health care service use and lead to an increased rate of mortality and morbidity and (4).

An ideal weight loss strategy is designed to yield optimal changes in body composition by reducing excess fat mass, while preserving muscle mass. However, weight loss interventions that preferentially decrease fat mass are challenging in older persons, as the concomitant muscle mass loss may exacerbate sarcopenia. Of note, increasing the fat-to-muscle loss ratio during weight management is more complicated in older people (5) due to their lower physical activity and coexisting chronic diseases.

Calorie restriction is a major catabolic stimulus and the mainstay of dietary interventions in weight reduction and leads to the loss of both fat and lean mass (6–8). Studies have shown that increasing total protein intake (1.2 – 1.5 g/kg body weight/d) can preserve muscle mass and reduce fat mass during weight loss (9, 10). Recent studies have suggested that within-day distribution of protein intake is another important modifier of body composition (11–13). The importance of equal distribution of protein intake throughout the day (~30g per meal) stems from a main concept that a threshold of high quality protein must be reached at each meal to maximally stimulate muscle protein synthesis (14, 15), particularly in older people who are experiencing blunted muscle protein anabolism (16). However, the majority of the studies addressing protein intake distribution and body composition were conducted during an energy-balanced diet/ usual calorie intake or under a hypocaloric diet in young obese adults over a short period of time (12). For example, we have previously shown that a more evenly distributed protein intake within-day is associated with higher lean mass (13) and muscle strength (17) in community-dwelling older men and women. Yet, the role of within-day distribution of protein intake on body composition in obese older adults undergoing intentional weight loss is unclear.

To determine the association between changes in mealtime dietary protein intake and improvements in body composition under a hypocaloric diet, we performed a secondary analysis of our previous long-term randomized controlled trial of Wellness for Elders through Lifestyle and Learning (WELL) (18, 19). In this trial, 36 overweight/obese older adults underwent 12 months of calorie restriction and exercise intervention vs. exercise alone with intensive dietary and body composition assessment. We hypothesize that changing the pattern of protein intake to a more even distribution within the day, independent of the protein quantity, is associated with greater weight loss during a one-year caloric restriction and physical activity intervention in over weight/obese older men and women.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

A total of 36 older individuals (age 70.6 ± 6.1 years) were enrolled in a one-year pilot randomized controlled trial called the Wellness for Elders through Lifestyle and Learning (WELL) study. Participant recruitment and screening have been described in detail elsewhere (18, 19). In brief, community-dwelling older (≥ 60 years) and overweight to obese (BMI between 28.0 and 39.9 kg/m2) men and women with a sedentary lifestyle (formal exercise < 3 times per week for a total time of < 90 min/week) from the greater McKeesport, PA area were invited by mail. Those who were interested (n=193) were telephone screened for the assessment of initial eligibility followed by two screening visits. Inclusion criteria were: 1) self-reported ability to walk 1/4 mile (2–3 blocks); 2) ability to walk 400 m in < 15 minutes without the use of an assistive device; 3) the ability and willingness to complete an activity log and food diary and to attend meetings and physical activity sessions in McKeesport, PA; and 4) the willingness to be randomized to either intervention program. Exclusion criteria consisted of: 1) severe medical conditions preventing participation in a diet and/or exercise intervention; 2) cognitive impairment (Modified Mini-Mental State Exam score < 80 or diagnosis of dementia); 3) inappropriate age or BMI; 4) weight loss of > 4.5 kg in the past four months; and 4) consumption of medications for obesity.

Eligible participants were randomized into either the Physical Activity plus Weight Loss (PA+WL, n=21) or Physical Activity plus Successful Aging Health Education (PA+SA, n=15) group. Randomization was performed by using a Microsoft Access-based random-number generating algorithm with stratification by age and sex. All of the participants provided written informed consent, and the research protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Interventions

Physical Activity Program

All participants, regardless of their group assignment, received the physical activity intervention (PA). The PA program was divided into three phases; adoption (weeks 1–8), transition (weeks 9–24), and maintenance (weeks 25–52). The aim of this three-phase program was to facilitate a gradual transition of the exercise training from the clinic setting into the participants’ daily routine.

During the adoption phase, participants were required to attend 3 center-based exercise sessions per week. Each session was ~60 minutes and mainly focused on treadmill walking followed by lower extremity resistance training, balance exercises and stretching. The goal was to increase treadmill walking to at least 150 min/week by week 9. During the transition phase, center-based exercise sessions were reduced to 2 sessions per week supplemented with one or more home-based sessions. During the maintenance phase, participants were expected to perform exercise at least 3 times per week at home. They also had the option to participate in one center-based exercise session per week.

Weight Loss Intervention

The goal was to achieve 7% weight loss by 6 months and to maintain it for the remainder of the trial in participants in the PA+WL arm. Participants were assigned to one of the following daily goals as recommended by the Diabetes Prevention Program: 1,200 kcal/day (33 g fat) for participants with an initial weight of 120–170 lbs, 1,500 kcal/day (42 g fat) for participants with a weight of 175–215 lbs, 1,800 kcal/day (50 g fat) for participants with a weight of 220–245 lbs, and 2,000 kcal/day (55 g fat) for participants weighing >250 lbs (20). Participants were advised to reduce dietary fat to ~25% of total energy intake, consume mono- and poly- unsaturated fat instead of saturated fat and cholesterol, and include at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables and 6 servings of grains, especially whole grains, in their daily diet. Of note, no recommendations were provided to the participants about the within-day distribution of dietary protein intake in the original RCT.

Participants received 24 weekly, 2 bi-monthly, and 5 monthly sessions led by a nutritionist. Participants were asked to keep food records for at least 6 days per week during the first 6 months and monthly thereafter. Participants were weighed at each session, their performance was evaluated and strategies to achieve the recommended calorie intake were discussed. If a participant had difficulty adhering to the WL intervention, the study nutritionist scheduled a one-on-one session with the participant. The overall adherence to this arm of the intervention was assessed by determining the percentage of the participants who met the weight loss goal.

Successful Aging (SA) Health Education Intervention

Participants randomized into PA+SA attended successful aging health education workshop series once a month (12 sessions in total each lasted 60-minutes). The workshops were based on “The Ten Keys to Healthy Aging™” (21) and the SA program developed for Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders-Pilot Study (22).

2.3. Outcome measurements

The following clinical and body composition data were recorded at baseline and two follow-up visits at 6 and 12 months after the enrollment.

I. Clinical measures

Body weight (kg) and height (cm) were measured to calculate BMI (kg/m2). Participants also completed questionnaires on sociodemographic and medical history. Physical activity (minutes/week) was quantified by the Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors (CHAMPS) physical activity questionnaire (23). The CHAMPS questionnaire was also used to assess adherence to the PA intervention.

II. Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA)

Total body lean mass (excluding bone) and fat mass were assessed by DXA (Hologic QDR 4500, software version 12.3; Bedford, MA) (24). Appendicular lean mass (aLM) was calculated as the sum of upper and lower extremity lean masses.

III. Computed Tomography (CT)

Axial CT scans (9800 Advantage, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) were used to quantify cross-sectional areas (CSA) of total, visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat as well as CSA of mid-thigh muscle, intramuscular fat and muscle density (Hounsfield Unit, HU), using established methods (18, 25, 26).

IV. Dietary assessments

Dietary intake was assessed by three-day food records at baseline, 6-month and 12-month follow-ups. At the beginning of the study, participants were instructed on how to report the intake of all foods and beverages using household measures or a scale as well as the time of intake. Food records were analyzed by Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) software developed at the Nutrition Coordinating Center of the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health.

Total protein intake was calculated by the nutrient residual energy-adjusted method (13). Absolute protein intake was regressed on total energy intake to compute residuals to remove the effect of total energy intake on protein intake. To assess mealtime distribution of protein intake, we categorized protein consumption based on the time of intake into; breakfast (5:00 – 10:59), lunch (11:00 – 16:59) and dinner (17:00 – 1:00). Additionally, the evenness of protein intake distribution across the three meals was calculated for each participant using the coefficient of variation (CV), as CV= SD of protein intake (g/meal) / mean protein intake (g/d) (13). The mean CV averaged over the 3 days was then calculated. Lower protein CV values reflect the evenness of within-day protein intake. Participants’ diet remained stable during the two follow up visits at 6 and 12 months compared to the baseline intake. Therefore, we pooled the food records obtained at 6 and 12 months, as the participants’ representative diet during the one-year follow up.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Participants’ characteristics are shown as means ± SDs for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables by intervention groups. Baseline and 1-y changes (i.e., 12months – baseline) were compared within and between PA+SA and PA+WL groups using parametric (i.e., paired-sample t-test and independent sample t-test) and nonparametric (i.e., Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney U test) tests. General linear model, Univariate ANOVA, was used to test the association between changes in protein CV and body composition by intervention group, controlled for their baseline values, total calorie and protein intake. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Version 24 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Participants characteristics

A total of 36 participants were included in this study (n=21 in the PA+WL group; n=15 in the PA+SA group). Baseline age was 71.0 ± 5.8 years. The majority of participants were women (83%) and Caucasian (83%).

Body composition

Anthropometrics and DXA

Body weight, BMI, fat mass and aLM were comparable between the intervention groups at baseline (Table 1). After one year, participants in PA+WL experienced a significant decline in weight (5.4%) and BMI (5.1%) compared to those in PA+SA (1% and 0.7%, respectively), P < 0.05 (Table 1). We also observed significant declines in the whole body fat mass (9%, P < 0.001) and aLM (4.5%, P < 0.01) within the PA+WL group; and trends towards reductions in the PA+SA group arm (3.3%, P = 0.06 and 1.6%, P= 0.08, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline and 1-y changes in body composition and nutrient intake by intervention program; WELL Study

| PA+WL |

PA+SA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N= 21 | P within | N= 15 | P within | P between | |

|

| |||||

| Age, y | 71.29 ± 5.90 | 70.53 ± 5.94 | 0.71 | ||

| Women, n (%) | 17 (81%) | 13 (86.7) | 0.65 | ||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 19 (90.5) | 11 (73.3) | 0.17 | ||

| Physical activity, min/wk | 716.43 ± 451.20 | 1025.00 ± 595.82 | 0.102 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | 217.14 ± 576.51 | 0.121 | 116.00 ± 450.87 | 0.271 | 0.58 |

| Body composition | |||||

| Weight, kg | 89.76 ± 10.04 | 85.38 ± 6.52 | 0.15 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −4.86 ± 6.11 | 0.004 | −0.83 ± 3.00 | 0.32 | 0.031 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.36 ± 3.28 | 32.15 ± 3.05 | 0.292 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −1.70 ± 2.27 | 0.0041 | −0.21 ± 1.01 | 0.681 | 0.020 |

| DXA | |||||

| Fat mass, kg | 37.95 ± 5.86 | 35.88 ± 6.47 | 0.32 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −3.43 ± 3.21 | 0.000 | −1.20 ± 2.19 | 0.061 | 0.035 |

| aLM, kg | 20.59 ± 3.72 | 19.70 ± 2.84 | 0.472 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −0.92 ± 1.28 | 0.004 | −0.31 ± 0.64 | 0.081 | 0.13 |

| CT Abdomen | |||||

| Total Fat, cm2 | 661.46 ± 134.14 | 569.57 ± 97.58 | 0.036 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −81.53 ± 104.81 | 0.005 | −26.47 ± 77.79 | 0.24 | 0.12 |

| Subcutaneous Fat, cm2 | 443.72 ± 124.46 | 389.07 ± 93.40 | 0.0972 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −46.71 ± 73.54 | 0.019 | −24.77 ± 63.77 | 0.311 | 0.40 |

| Visceral Fat | 217.75 ± 61.26 | 179.80 ± 47.89 | 0.062 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −34.82 ± 42.84 | 0.004 | −0.95 ± 29.28 | 0.91 | 0.021 |

| CT mid-thigh | 0.001 | ||||

| Intramuscular fat, cm2 | 12.52 ± 3.57 | 13.42 ± 5.52 | 0.60 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −3.20 ± 2.22 | 0.000 | −1.83 ± 2.64 | 0.028 | 0.14 |

| Muscle density, HU | 39.56 ± 3.13 | 40.12 ± 3.29 | 0.272 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | 0.66 ± 1.54 | 0.11 | 0.24 ± 1.41 | 0.55 | 0.46 |

| Quadriceps Muscle, cm2 | 49.15 ± 10.76 | 50.07 ± 10.64 | 0.962 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −2.71 ± 3.50 | 0.007 | −1.32 ± 5.62 | 0.251 | 0.222 |

| Dietary intake | |||||

| Energy, kcal | 1711.22 ± 330.92 | 1729.99 ± 339.11 | 0.87 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −245.36 ± 393.35 | 0.012 | −87.14 ± 438.05 | 0.49 | 0.29 |

| Fat, %kcal | 31.12 ± 8.15 | 34.22 ± 6.50 | 0.25 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −3.32 ± 6.82 | 0.042 | 0.68 ± 7.79 | 0.76 | 0.13 |

| Carbohydrate, %kcal | 51.19 ± 8.75 | 49.54 ± 7.27 | 0.57 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | 2.15 ± 8.11 | 0.25 | −2.24 ± 7.16 | 0.28 | 0.12 |

| Protein, %kcal | 17.40 ± 3.46 | 15.93 ± 2.87 | 0.20 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | 1.27 ± 2.96 | 0.07 | 1.28 ± 3.84 | 0.25 | 1.00 |

| Protein, g/kg BW/d | 0.88 ± 0.19 | 0.80 ± 0.18 | 0.25 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −0.07 ± 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.02 ± 0.28 | 0.76 | 0.27 |

| Protein, energy adjusted g/d | 72.68 ± 12.61 | 67.29 ± 12.08 | 0.22 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −2.31 ± 12.03 | 0.40 | −1.10 ± 16.34 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| Protein distribution, CV | 0.81 ± 0.22 | 0.70 ± 0.20 | 0.142 | ||

| Δ BL - 12m | −0.13 ± 0.23 | 0.018 | −0.02 ± 0.29 | 0.81 | 0.212 |

Values are means ± SDs, unless otherwise indicated.

Pwithin values were derived by paired-sample t-test, unless otherwise indicated.

Pbetween values were derived by independent sample t-test unless otherwise indicated.

derived by using Wilcoxon

derived by using independent sample Mann-Whitney U test

y, year; PA, Physical activity; WL, weight loss; SA, successful aging health education; BL, baseline; 12m, 12-month; HU, Hounsfield Unit; CSA, cross-sectional area; CV, coefficient of variation; BMI, Body Mass Index; DXA, dual x-ray absorptiometry; aLM, appendicular lean mass; CT, computed tomography.

Abdominal CT

Total abdominal fat was higher in the PA+WL group compared to PA+SA at baseline, P= 0.04 (Table 1). There was a significant reduction in total (12.3%, P < 0.01), visceral (16%, P < 0.01) and subcutaneous (10.5%, P < 0.05) abdominal fat within the PA+WL arm of the study after one year; but not in the PA+SA group, Table 1.

Mid-thigh CT

Intramuscular fat, muscle density and muscle area were comparable between the programs at baseline (Table 1). Intramuscular fat significantly declined in both PA+WL (25.6%, P < 0.001) and PA+SA (13.6%, P < 0.05) groups. However, the 12-month decrease in the quadriceps muscle area was only significant in the PA+WL group (5.5%, P < 0.01).

Dietary intake

Total energy and macronutrients (fat, carbohydrates and protein) intakes were similar at baseline between the intervention groups. Participants in the PA+WL group reduced their total calorie intake by 4.3% (P= 0.012) and fat intake by 3.3% (P= 0.042) during the 1-year follow-up. However, nutrient intakes remained unchanged in the PA+SA group, Table 1.

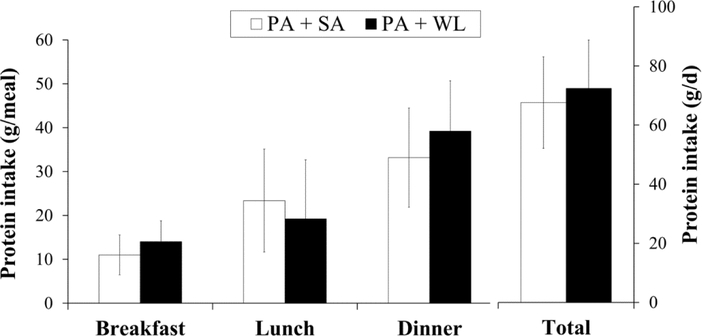

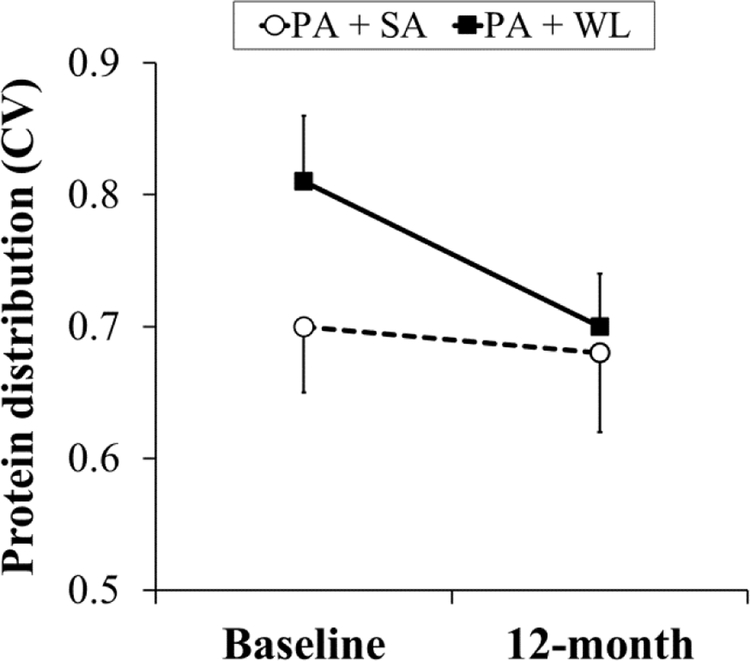

In both groups, baseline protein intake was comparably skewed towards dinner (49.1% for PA+SA and 54.1% for PA+WL) (Figure 1). Breakfast (16.3% in PA+SA and 19.3% in PA+WL group) and lunch (34.6% in PA+SA and 26.5% in PA+WL) had smaller contribution to the total protein intake. However, the pattern of protein intake changed towards a more even within-day distribution in participants in the PA+WL arm during the intervention (protein intake CV of 0.81 ± 0.22 at baseline vs. 0.70 ± 0.19 during the follow ups, P<0.05) (Figure 2). Within-day distribution of protein intake remained unchanged in the PA+SA group during the follow ups.

Fig 1.

Mean ± SD of baseline protein intake per meal and per day by intervention program. PA, physical activity; SA, successful aging health education; WL, weight loss

Fig 2.

Mean ± SE of baseline and 1-y change of protein intake distribution.

CV, coefficient of variation, PA, physical activity; SA, successful aging; WL, weight loss P obtained by paired sample t-test

Protein intake distribution and body composition

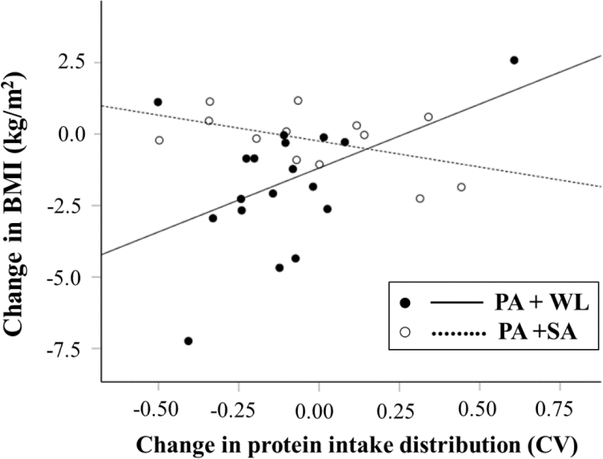

Table 2 shows the associations between changes in protein intake distribution and changes in BMI, weight, subcutaneous abdominal fat and quadriceps muscle cross-sectional area, after controlling for their baseline values, total calorie and protein intake. For participants in the PA+WL group, the transition towards a more even distribution of protein intake throughout the day (i.e., decrease in protein intake CV) was independently associated with a greater decline in BMI (P <0.05) and abdominal subcutaneous fat (P <0.05) (Figure 3 and Table 2). Similarly, the decline in protein CV was associated with a trend toward higher weight loss after one year in the PA+WL group (P= 0.06). However, changes in protein CV were not associated with changes in BMI, abdominal subcutaneous fat or weight in participants in the PA+SA group. Moreover, changes in within-day distribution of protein was not related to changes in mid-thigh quadriceps muscle cross-sectional area (Table 2), whole body fat mass, lean mass, abdominal visceral fat and mid-thigh intramuscular fat (data not shown) in either group. Of note, neither total calorie intake nor total protein intake was significantly related to body composition changes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between 1-y change (Δ) in within-day protein intake distribution and body composition by intervention program.

| PA+WL |

PA+SA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE | P | β ± SE | P | |

|

| ||||

| 1-y Δ BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| 1-y Δ protein CV | 5.284 ± 2.407 | 0.047 | −1.602 ± 1.102 | 0.18 |

| 12m Protein intake, g/d | 0.029 ± 0.041 | 0.49 | 0.013 ± 0.026 | 0.64 |

| 12m Total energy intake, kcal | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.29 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.26 |

| BL BMI, kg/cm2 | 0.079 ± 0.163 | 0.64 | 0.012 ± 0.098 | 0.91 |

| 1-y Δ Weight, kg | ||||

| 1-y Δ protein CV | 13.768 ± 6.645 | 0.059 | −4.309 ± 3.656 | 0.27 |

| 12m Protein intake, g/d | −0.060 ± 0.112 | 0.60 | 0.033 ± 0.098 | 0.74 |

| 12m Total energy intake, kcal | 0.005 ± 0.005 | 0.37 | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.49 |

| BL weight, kg | −0.030 ± 0.142 | 0.84 | 0.052 ± 0.165 | 0.76 |

| 1-y Δ Subcutaneous abdominal fat, cm2 | ||||

| 1-y Δ protein CV | 161.38 ± 72.562 | 0.046 | 30.984 ± 82.927 | 0.72 |

| 12m Protein intake, g/d | −0.999 ± 1.258 | 0.44 | −1.330 ± 2.828 | 0.65 |

| 12m Total energy intake, kcal | 0.104 ± 0.055 | 0.08 | 0.004 ± 0.049 | 0.93 |

| BL Subcutaneous abdominal fat, cm2 | −0.213 ± 0.168 | 0.23 | 0.416 ± 0.228 | 0.11 |

| 1-y Δ Quadriceps Muscle CSA, cm2 | ||||

| 1-y Δ protein CV | 7.757 ± 3.884 | 0.071 | −7.822 ± 8.073 | 0.37 |

| 12m Protein intake, g/d | 0.007 ± 0.072 | 0.92 | 0.040 ± 0.180 | 0.83 |

| 12m Total energy intake, kcal | 0.004 ± 0.003 | 0.23 | 0.000 ± 0.005 | 0.99 |

| BL Quadriceps Muscle CSA, cm2 | −0.031 ± 0.083 | 0.72 | 0.047 ± 0.196 | 0.82 |

General linear model (Univariate ANOVA)

BL, baseline; CSA, cross-sectional area; CV, coefficient of variation; PA, physical activity; SA, successful aging; WL, weight loss; BMI, Body Mass Index.

Fig 3.

Relationship between 1-y changes in protein intake distribution and BMI by intervention program.

PA, physical activity; SA, successful aging education program; WL, weight loss; BMI, Body Mass Index.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that a transition towards a more even distribution of protein intake throughout the day (i.e., decrease in protein intake CV value) under a hypocaloric dietary and physical activity intervention was independently associated with a greater decline in weight, BMI and abdominal subcutaneous fat.

In a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults from the 1999–2002 NHANES data (n=1,081 people; age 50–85 years), it has been shown that the majority of daily protein intake is consumed during the evening meal (44%) (27). In agreement with this observation, within-day pattern of protein intake among our study participants was skewed towards dinner, while breakfast minimally contributed to total daily protein intake.

Over the past several years, there has been a growing attention to the role of distribution of daily protein intake, in addition to its quantity, as a strategy to maximally stimulate muscle protein synthesis (14, 15). A meal-driven approach of protein intake throughout the day may be particularly important in senior adults who are experiencing a blunted muscle protein anabolism, i.e., anabolic resistance of aging (16). It has been shown that higher doses of essential amino acids (10–15 g/meal) compared to low doses (~7.5 g/meal) are required to stimulate muscle protein anabolism in older individuals to a similar extent as in younger adults (11, 28). However, one potential limitation is that the acute changes in muscle protein synthesis may not translate into enduring changes in body composition over long periods of time (29). A few longitudinal studies have also suggested potentially beneficial effects of equal distribution of protein intake on body composition in older adults (13). However, the majority of these studies were performed on subjects who consumed a balanced-calorie diet with only a few studies addressing the associations between distribution of protein intake and body composition parameters during a hypocaloric weight-loss regimen (12).

In the present study, we extended the scope of the previous investigations by exploring the potential association between within-day distribution of protein intake and adipose tissue loss. We noted a shift in within-day distribution of protein intake in the intervention group (PA+WL); where protein intake was re-distributed from dinner to other meals, particularly lunch (has not been shown in results). Moreover, shifting to a more even pattern of protein intake was independently associated with greater weight and subcutaneous abdominal fat mass losses in participants in the PA+WL group. One possible mechanism linking more even protein intake to weight loss is the satiation effect of protein ingestion, leading to reduction in food intake. Also, increased thermogenesis associated with protein consumption may contribute to weight loss by increasing the energy expenditure (30). However, our finding is in contrast to a recent short-term (16 week) clinical trial in which within-day distribution of protein intake had no significant effect on fat mass reduction in young overweight adults on an energy-restricted and resistance training program (12). The differences in the study population (older vs. younger adults) and the study period (12 month vs. 16 week) may contribute to the inconsistencies in our results.

To address the relationship between the intake of other nutrients and weight loss, in our study, the association between protein intake distribution and weight loss was assessed after adjustment for total calorie and protein intake. Of note, neither total daily energy intake nor protein intake were related to the observed weight changes in our study. One possibility for the lack of association between other dietary factors and body composition is that the magnitude of changes in calorie and macro-nutrient intake was not sufficiently different from baseline to detect measurable effects on body composition. Additionally, the observed independent association between even protein intake within-day and weight loss may be related to the circadian timing of protein intake. It has been shown that skewed consumption of foods towards dinner (i.e., during the circadian evening or night) is associated with increased body fat independent of total calorie or nutrient contents (31).

A strength of the current study was the collection of dietary data through food records that reduces the potential recall bias that is observed with 24h food recalls or food frequency questionnaires. Dietary data collection through food recall also allowed us to accurately determine the within-day distribution of protein intake. Additionally, the quantification of within-day protein intake distribution by calculating protein CV as a continuous variable, as opposed to categories with arbitrary cut offs, makes our statistical approach more robust and generalizable to populations with various patterns of protein intake.

This study has a few limitations to consider. First, there was a small number of participants, as this was a pilot clinical trial. Also, study participants were mostly Caucasians and female, which limits the generalizability of our data to other races or men. Additionally, the absence of a WL and SA intervention group limits us to discriminate the effect of protein intake distribution on weight loss under hypocaloric diet alone from the physical activity.

In summary, our results show that mealtime distribution of protein intake throughout the day was associated with improved weight and fat mass loss under hypocaloric diet combined with exercise. This finding may have implications in the optimization of weight management interventions in overweight/obese older people by allowing for a preferential loss of fat mass.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors’ contributions were as follows—SF and JAC: designed the research; ABN, NWG, and AJS: designed and conducted the WELL study; SF: analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; RMB: provided statistical advice; SF and ABN had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Sources of support

This work was supported by a Center for Disease Control cooperative agreement (1 U48 DP000025). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00714506

Abbreviation list:

- BMI

Body mass index

- PA

Physical activity

- SA

Successful aging health education

- WL

Weight loss

- CV

Coefficient of variation

- WELL

Wellness for Elders through Lifestyle and Learning

- CHAMPS

Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors

- DXA

Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry

- aLM

Appendicular lean mass

- CT

Computed Tomography

- CSA

Cross-sectional areas

- NDSR

Nutrition Data System for Research

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: SF, JAC, AJS, NWG, RMB, ABN have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT:

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board. All participants signed informed consent after demonstrating a basic understanding of the role and responsibilities of a study participant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fakhouri TH, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among older adults in the United States, 2007–2010. NCHS data brief. 2012. Sep(106):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. Jama. 2014. Feb 26;311(8):806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman AB. Obesity in Older Adults. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2009;14(1). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decaria JE, Sharp C, Petrella RJ. Scoping review report: obesity in older adults. International journal of obesity (2005). 2012. Sep;36(9):1141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cava E, Yeat NC, Mittendorfer B. Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md). 2017. May;8(3):511–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss EP, Racette SB, Villareal DT, Fontana L, Steger-May K, Schechtman KB, et al. Lower extremity muscle size and strength and aerobic capacity decrease with caloric restriction but not with exercise-induced weight loss. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 2007. Feb;102(2):634–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones PJ, Smith H, Paddags A, Hudson R, et al. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men. A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2000. Jul 18;133(2):92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen I, Fortier A, Hudson R, Ross R. Effects of an energy-restrictive diet with or without exercise on abdominal fat, intermuscular fat, and metabolic risk factors in obese women. Diabetes care. 2002. Mar;25(3):431–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leidy HJ, Carnell NS, Mattes RD, Campbell WW. Higher protein intake preserves lean mass and satiety with weight loss in pre-obese and obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2007. Feb;15(2):421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans EM, Mojtahedi MC, Thorpe MP, Valentine RJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Layman DK. Effects of protein intake and gender on body composition changes: a randomized clinical weight loss trial. Nutrition & metabolism. 2012. Jun 12;9(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mamerow MM, Mettler JA, English KL, Casperson SL, Arentson-Lantz E, Sheffield-Moore M, et al. Dietary protein distribution positively influences 24-h muscle protein synthesis in healthy adults. The Journal of nutrition. 2014. Jun;144(6):876–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson JL, Kim JE, Paddon-Jones D, Campbell WW. Within-day protein distribution does not influence body composition responses during weight loss in resistance-training adults who are overweight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017. Nov;106(5):1190–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farsijani S, Morais JA, Payette H, Gaudreau P, Shatenstein B, Gray-Donald K, et al. Relation between mealtime distribution of protein intake and lean mass loss in free-living older adults of the NuAge study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016. Sep;104(3):694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paddon-Jones D, Sheffield-Moore M, Zhang XJ, Volpi E, Wolf SE, Aarsland A, et al. Amino acid ingestion improves muscle protein synthesis in the young and elderly. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2004. Mar;286(3):E321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsanos CS, Kobayashi H, Sheffield-Moore M, Aarsland A, Wolfe RR. Aging is associated with diminished accretion of muscle proteins after the ingestion of a small bolus of essential amino acids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005. Nov;82(5):1065–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dardevet D, Remond D, Peyron MA, Papet I, Savary-Auzeloux I, Mosoni L. Muscle wasting and resistance of muscle anabolism: the “anabolic threshold concept” for adapted nutritional strategies during sarcopenia. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:269531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farsijani S, Payette H, Morais JA, Shatenstein B, Gaudreau P, Chevalier S. Even mealtime distribution of protein intake is associated with greater muscle strength, but not with 3-y physical function decline, in free-living older adults: the Quebec longitudinal study on Nutrition as a Determinant of Successful Aging (NuAge study). Am J Clin Nutr. 2017. Jul;106(1):113–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santanasto AJ, Glynn NW, Newman MA, Taylor CA, Brooks MM, Goodpaster BH, et al. Impact of weight loss on physical function with changes in strength, muscle mass, and muscle fat infiltration in overweight to moderately obese older adults: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of obesity. 2011;2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santanasto AJ, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Miljkovic I, Satterfield S, Schwartz AV, et al. Body Composition Remodeling and Mortality: The Health Aging and Body Composition Study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2017;72(4):513–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diabetes Prevention Program Research G. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes care. 2002;25(12):2165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sipila S, Multanen J, Kallinen M, Era P, Suominen H. Effects of strength and endurance training on isometric muscle strength and walking speed in elderly women. Acta physiologica Scandinavica. 1996. Apr;156(4):457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fielding RA, Katula J, Miller ME, Abbott-Pillola K, Jordan A, Glynn NW, et al. Activity adherence and physical function in older adults with functional limitations. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2007. Nov;39(11):1997–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2001. Jul;33(7):1126–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visser M, Fuerst T, Lang T, Salamone L, Harris TB. Validity of fan-beam dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for measuring fat-free mass and leg muscle mass. Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study--Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry and Body Composition Working Group. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 1999. Oct;87(4):1513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodpaster BH, Krishnaswami S, Resnick H, Kelley DE, Haggerty C, Harris TB, et al. Association between regional adipose tissue distribution and both type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in elderly men and women. Diabetes care. 2003. Feb;26(2):372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodpaster BH, Chomentowski P, Ward BK, Rossi A, Glynn NW, Delmonico MJ, et al. Effects of physical activity on strength and skeletal muscle fat infiltration in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 2008. Nov;105(5):1498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loenneke JP, Loprinzi PD, Murphy CH, Phillips SM. Per meal dose and frequency of protein consumption is associated with lean mass and muscle performance. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2016. Dec;35(6):1506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, Cesari M, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Morley JE, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013. Aug;14(8):542–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell CJ, Churchward-Venne TA, Cameron-Smith D, Phillips SM. What is the relationship between the acute muscle protein synthesis response and changes in muscle mass? Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 2015. Feb 15;118(4):495–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paddon-Jones D, Westman E, Mattes RD, Wolfe RR, Astrup A, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Protein, weight management, and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008. May;87(5):1558s–61s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHill AW, Phillips AJ, Czeisler CA, Keating L, Yee K, Barger LK, et al. Later circadian timing of food intake is associated with increased body fat. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2017;106(5):1213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]