Abstract

Background

Injuries are a significant public health burden and alcohol intoxication is recognised as a risk factor for injuries. Increasing attention is being paid to supply‐side interventions that aim to modify the environment and context within which alcohol is supplied and consumed.

Objectives

To quantify the effectiveness of interventions implemented in the server setting for reducing injuries.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases to November 2008; Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PsycEXTRA, ISI Web of Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science, TRANSPORT and ETOH. We also searched reference lists of articles and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised controlled trials (NRTs) and controlled before and after studies (CBAs) of the effects of interventions administered in the server setting that attempted to modify the conditions under which alcohol is served and consumed, to facilitate sensible alcohol consumption and reduce the occurrence of alcohol‐related harm.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened search results and assessed the full texts of potentially relevant studies for inclusion. Data were extracted and methodological quality was examined. Due to variability in the types of interventions investigated, a pooled analysis was not appropriate.

Main results

Twenty‐three studies met the inclusion criteria. Overall methodological quality was poor. Five studies used an injury outcome measure; one of these studies was randomised, the remaining four where CBA studies.

The RCT targeting the alcohol server setting environment with an injury outcome compared the introduction of toughened glassware (experimental) to annealed glassware (control) on the number of bar staff injuries; a greater number of injuries were detected in the experimental group (relative risk 1.72, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.59).

One CBA study investigated server training and estimated a reduction of 23% in single‐vehicle, night‐time crashes in the experimental area (controlled for crashes in the control area). Another CBA study examined the impact of a drink driving service, and reported a reduction in injury road crashes of 15% in the experimental area, with no change in the control; no difference was found for fatal crashes. In a CBA study investigating the impact of an intervention aiming to reduce crime in drinking premises, the study authors found a lower rate of all crime in the experimental premises (rate ratio 4.6, 95% CI 1.7 to 12, P = 0.01); no difference was found for injury (rate ratio 1.1 95% CI 0.1 to 10, P = 0.093). A CBA study investigating the impact of a policy intervention reported that pre‐intervention the serious assault rate in the experimental area was 52% higher than the rate in the control area. After intervention, the serious assault rate in the experimental area was 37% lower than in the control area.

The effects of such interventions on patron alcohol consumption is inconclusive. One randomised trial found a statistically significant reduction in observed severe aggression exhibited by patrons. There is some indication of improved server behaviour but it is difficult to predict what effect this might have on injury risk.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence from randomised controlled trials and well conducted controlled before and after studies to determine the effect of interventions administered in the alcohol server setting on injuries. Compliance with interventions appears to be a problem; hence mandated interventions may be more likely to show an effect. Randomised controlled trials, with adequate allocation concealment and blinding are required to improve the evidence base. Further well‐conducted, non‐randomised trials are also needed when random allocation is not feasible.

Plain language summary

Are interventions that are implemented in alcohol server settings (e.g. bars and pubs) effective for preventing injuries?

Injuries are a significant public health burden and alcohol intoxication (i.e. drunkenness) is recognised as a risk factor for injuries; indeed the effects of alcohol lead to a considerable proportion of all injuries. Alcohol‐associated injuries are a problem in both high‐ and low‐income countries.

Many interventions to reduce alcohol‐related injuries have a demand‐side focus and aim to reduce individuals' demand and consequently consumption of alcohol. However, there is increasing attention on supply‐side interventions, which attempt to alter the environment and context within which alcohol is supplied and consumed; the aim being to modify the drinking and/or the drinking environment so that potential harm is minimised.

This systematic review was conducted to examine the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions implemented in the alcohol server setting for reducing injuries. The authors of this systematic review examined all studies that compared server settings which received an intervention aimed at facilitating sensible alcohol consumption and/or preventing injuries, to server settings which did not receive such an intervention.

The authors found 23 studies; only five of these measured the effect on injury, the remaining 18 measured the effect on behaviour (by the patrons and/or the servers of the alcohol within the premises). The studies investigated a range of interventions involving server training, health promotion initiatives, a drink driving service, a policy intervention and interventions that targeted the server setting environment.

The authors concluded that there is insufficient high quality evidence that interventions in the alcohol server setting are effective in preventing injuries. The evidence for the effectiveness of the interventions on patron alcohol consumption was found to be inconclusive. There is conflicting evidence as to whether server behaviour is improved and it is difficult to predict what effect this might have on actual injury risk.

Lack of compliance with interventions seems to be a particular problem; hence mandated interventions or those with associated incentives for compliance, may be more likely to show an effect. The methodology of future evaluations needs to be improved. The focus of research should be broadened to investigate the effectiveness of interventions other than server training, where previous research dominates. When the collection of injury outcome data is not feasible, research is needed to identify the most useful proxy indicators.

Background

Description of the condition

Injuries are a significant global public health burden. During the year 2000, it is estimated that five million people worldwide died from injuries. Globally they account for 9% of deaths and 12% of the burden of disease (Peden 2002a). This burden is predicted to worsen; by 2020 it is estimated that deaths from injuries will increase to 8.4 million per year (Murray 1997a). Injuries rank among the leading causes of mortality and burden of disease in all regions, affecting people of all ages and income groups (Peden 2002b).

Injuries can be caused by a number of factors, alcohol being just one. Hence, when considering the public health burden, it is useful to refer to the proportion of all injuries that can be attributed to alcohol. The 'attributable fraction' represents the extent to which injury rates would fall if alcohol use was eliminated. By conducting a meta‐analysis of epidemiological research (primarily case‐control and case‐series studies) English et al (English 1996) estimated the alcohol‐attributable fractions for a range of disorders. Britton 2001 used the figures from English 1996 and estimated that for England & Wales in 1996, alcohol was responsible for: approximately 75,000 of premature life years lost, 99 of 210 (47%) deaths from assaults, 66 of 174 (38%) deaths from accidental drowning, 1176 of 3616 (33%) deaths from accidental falls, 178 of 405 (44%) deaths from fire‐related injuries, 758 of 2948 (26%) deaths from motor vehicle crashes, and 997 of 3442 (29%) suicides. However, it should be noted that all estimates of attributable fractions assume causality and can only be as accurate as the studies upon which they are based. The influence of bias, such as confounding, may lead to less accurate estimates and should be considered. Nevertheless, alcohol can be considered to cause a considerable proportion of all injuries.

Evidence that alcohol consumption has some beneficial health effects complicates public health policy in this area. Research has indicated that alcohol, consumed in moderation, is protective against coronary heart disease (CHD) and ischaemic stroke, particularly in the middle‐aged and elderly population (Britton 2001). Injuries resulting from alcohol tend to affect drinkers at younger ages, especially in the 15 to 29 years age group, which results in greater years of potential life lost and disability over the proposed life span (WHO 1999). CHD is rare in those younger than 50 years; hence most of the averted deaths are amongst the older ages. Thus, in terms of years of life lost, the adverse effects of drinking may outweigh any protection alcohol offers against CHD (Jernigan 2000).

The problems of alcohol and injury are not confined to developed countries. Indeed, the situation is particularly alarming in lower and middle‐income countries, where alcohol consumption is increasing, injury rates are high, and appropriate public health policies have not been implemented (Poznyak 2001). Most of the increase in global alcohol consumption has occurred in developing countries (WHO 2002). In sub‐Saharan Africa, where ischaemic heart disease is rare, the protective effects of alcohol are only of marginal public health importance while alcohol is a major cause of death and disability from injury (Murray 1997b).

How the intervention might work

Traditionally, injuries were perceived as random, unavoidable 'accidents', but in recent decades perceptions have altered and injuries are increasingly considered as preventable, non‐random events (Peden 2002b).

In the past, many interventions and much of the intervention research focused on individuals, targeting those considered at highest risk of alcohol‐related problems. However, it has been suggested that such a focus on 'problem drinkers' is unlikely to result in a sustained decrease in problems at the population level, because the majority of alcohol‐related problems are attributable to the substantial number of moderate drinkers who occasionally drink to intoxication (Babor 2003). It is alcohol intoxication (i.e. drunkenness) that is recognised as a strong risk factor for injury, as opposed to long‐term exposure to alcohol; thus preventing alcohol intoxication is a potentially effective approach for reducing the harm arising from alcohol (Babor 2003). Interventions that target all drinkers often have a demand‐side focus, aiming to reduce individuals' demands and consequently consumption of alcohol, mainly through educational interventions. An alternative is to take a 'supply‐side' approach. The principle of a supply‐side approach is to implement interventions that modify the environment within which alcohol is supplied, and the drinking context. Observational research has suggested that the environment of alcohol serving premises can impact on the risk of injury. Specifically relating to violence, factors such as a lack of seating, loud music, overcrowding, lack of available food are considered risk factors (Graham 1997; Homel 1992; Homel 2001; Rehm 2003).

Implementation of interventions in the server setting (e.g. bars, pubs, retailers) has the potential to maximise exposure; every alcohol consumer has contact with the industry in one form or another, while only a small proportion of these consumers come into contact with government services because of their alcohol consumption (Strategy Unit 2004). O'Donnell 1985 estimated that approximately 50% of alcohol‐related traffic crashes involve the prior consumption of alcohol on licensed premises, and a strong association between public violence and drinking on licensed premises is documented (Stockwell 2001). Hence, when such risky consumption occurs in server settings, it makes them a logical focus for prevention efforts.

Efforts applied to the server setting imply a level of acceptance that alcohol consumption will occur but aim to modify the drinking and/or the drinking environment so that potential harm is prevented. Interventions within server settings can range from the way alcohol is packaged, promoted and sold, to the overall management and policy of the establishment within which it is consumed. Such interventions include server training, use of alternatives to standard drinking glassware (for example, toughened glass, plastic containers), discontinuation of alcoholic drink promotions (for example, 'happy hours'), using server settings as sites for health promotion initiatives amongst others, which may be implemented individually or in combination.

Why it is important to do this review

Reviews of research are essential tools for health care workers, researchers, consumers and policy‐makers who want to keep up to date with evidence in their field. Systematic reviews enable a more objective appraisal of the evidence than traditional narrative reviews, and are important in demonstrating areas where the available evidence is insufficient and where further good quality trials are required (Egger 2001).

It is important that the effectiveness of interventions in the server setting is evaluated to aid policy decision‐making and priority setting. Graham 2000 published a comprehensive narrative literature review of preventive approaches for on‐premise drinking, and Shults 2001 conducted a systematic review to examine the effectiveness of server education specifically for preventing drink driving. However, no other systematic review attempting to quantify the effectiveness of all interventions delivered in the server setting on reducing all forms of injury has been identified. The purpose of this systematic review is to critically review the current evidence for the use of interventions delivered in the server setting for preventing injury.

Objectives

To quantify the effectiveness of interventions in the alcohol server setting for reducing injuries.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

The following randomised and non‐randomised study designs were eligible.

Randomised controlled trials

Participants are randomly allocated to intervention or control groups and followed up over time to assess any differences in outcomes.

Cluster randomised controlled trials

Groups of participants are randomly allocated to intervention or control groups and followed up over time to assess any differences in outcomes.

Non‐randomised controlled trials

The investigator has control over the allocation of participants to groups but does not use randomisation.

Controlled before and after studies

A follow‐up study of participants who have received an intervention and those who have not, measuring the outcome variable at both baseline and after the intervention period, comparing either final values if the groups are comparable at baseline, or change scores.

(Definitions adapted from those cited in Deeks 2003.)

Despite being more prone to bias than studies using random allocation, we decided to include non‐randomised controlled designs, in light of the practical constraints of conducting RCTs in this area.

Types of participants

Workers in licensed alcohol serving premises (e.g. bar staff, shop workers)

Owners and managers of alcohol serving premises

Patrons in licensed alcohol serving premises

Licensed alcohol serving outlets (e.g. retailers, pubs, bars, clubs, restaurants) including 'off‐licences' (i.e. premises which do not have a licence for on‐premise consumption, but sell alcohol for off‐premise consumption)

Areas of multiple licensed alcohol serving outlets (e.g. towns)

Types of interventions

Eligible interventions were those administered in the server setting that attempted to modify the conditions under which alcohol was served and consumed, to facilitate sensible alcohol consumption and reduce the occurrence of alcohol‐related harm. Studies of server interventions that were administered in a programme involving other ineligible (that is, not in the server setting) interventions were considered if outcomes attributed to the eligible server‐intervention component could be distinguished.

Legislative interventions such as server liability, licensing/opening hours, and advertising restrictions were not eligible.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Fatal injuries

Non‐fatal injuries

(Data on all alcohol‐related injuries was considered, irrespective of whether the injured individual had consumed alcohol or not.)

Secondary outcomes

Behaviour change (e.g. change in amount of alcohol consumed)

Knowledge change

Search methods for identification of studies

Searches were not restricted by date, language or publication status.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases;

Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register (searched November 2008),

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 4),

MEDLINE (January 1966 to November 2008),

EMBASE (1980 to November 2008),

PsycINFO (1806 to November 2008),

PsycEXTRA (1908 to November 2008),

ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) (1970 to November 2008),

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) (1970 to November 2008), Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S) (1990 to November 2008),

TRANSPORT (1988 to 2007/06),

ETOH (The Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Science Database; produced by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA); historic alcohol‐related research information covering the period from (1972 to 2003),

SIGLE (1980 to 2004/06),

SPECTR (September 2004),

Zetoc (1993 to September 2004),

National Research Register (issue 3/2004).

The original search strategy is presented in Appendix 1. The search strategy for the latest update is presented in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We searched the Internet, checked the reference lists of relevant studies and, where possible, contacted the first author of each included study to identify further potentially eligible articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We independently examined titles, abstracts, and keywords of citations from electronic databases for eligibility. We obtained the full text of all relevant records and independently assessed whether each met the pre‐defined inclusion criteria. We resolved disagreement by discussion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from each eligible study using a standard form that we had developed specifically for this review. We extracted data on the following:

study date and setting;

sample size;

study design;

method of allocation;

blinding of outcome assessment;

characteristics of intervention and control groups;

characteristics of intervention;

the outcomes evaluated;

results;

duration of follow up;

loss to follow up;

intention to treat.

Where necessary and possible, we sought additional information from researchers involved in the original studies.

We were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions, journal of publication, or results of the trials, because evidence for the value of this is inconclusive (Berlin 1997).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The Health Technology Assessment report, 'Evaluating non‐randomised intervention studies' (Deeks 2003), contains a systematic review of quality assessment tools used for non‐randomised studies and identifies six judged to be potentially useful for use in systematic reviews. For the present review, from these six, we selected a tool developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (Thomas 2003) to assess methodological quality of all the study designs. A modified framework of the Thomas 2003 quality tool was used to describe each of the included studies against the following criteria as available from the report;

Allocation bias (for example, was allocation to the experimental and control groups random and adequately concealed?)

Confounders (for example, did the groups under study differ in terms of distribution of potential confounders?)

Blinding (for example, were the outcome assessors blind to the allocation status of the participants?)

Data collection methods (for example, were outcome data collected through self‐report methods or more objective methods such as researcher observation or extracted from official records?)

Withdrawals and dropouts (for example, how many participants failed to complete the study and/or were lost to follow‐up?)

Intervention compliance (for example, what proportion of participants received the allocation intervention?)

Duration of follow‐up (for example, how long was/were the data collection period(s)?)

For the June 2010 update the above quality domains were incorporated into an assessment of the included studies risk of bias in accordance with the recommended approach presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We completed a risk of bias table for each study, incorporating a description of the study's performance against each of the above domains and our overall judgment of the risk of bias for each entry, as follows: 'Yes' indicates low risk of bias, 'Unclear' indicates unclear or unknown risk of bias, 'No' indicates high risk of bias.

Data synthesis

On inspection of the eligible studies, it was clear that there was a high degree of heterogeneity in terms of participants, interventions and outcomes (that is, clinical heterogeneity) which meant that a pooled analysis would not be appropriate. Therefore data were reviewed qualitatively for each study, presenting effect estimates, precision and statistical significance as reported. We calculated odds ratios (OR) and the mean difference (MD) for the RCTs where possible.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The combined search strategy identified approximately 3,550 studies, of which 71 were deemed to be potentially relevant based on title or abstract. After a full text review, 23 studies were judged to meet the inclusion criteria.

Included studies

The studies had been conducted in six countries; five in Australia, twelve in the USA, two in Canada, two in Sweden, one in South Africa and one in the UK, published over a 21‐year period (1987 to 2008).

Eight were randomised controlled trials, ten were non‐randomised controlled trials and five used a controlled before and after design. Fourteen studies used individual premises as the unit of allocation; one trial used individual servers and the remaining seven used areas containing multiple serving establishments (e.g. towns).

Sixteen studies compared a responsible server training intervention with no training (or a reduced training programme). Two studies investigated the effectiveness of delivering health promotion information in serving establishments. Two studies examined interventions that targeted the server setting environment. One study focused on the management policies of serving premises, one investigated the effectiveness of a driving service for intoxicated patrons, and one looked at promotion of the use of public breathalysers.

Five studies used an injury outcome. Seventeen studies collected data on behaviour (of servers and/or of patrons) and six studies collected data on changes in knowledge.

A more detailed description of the individual studies is presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

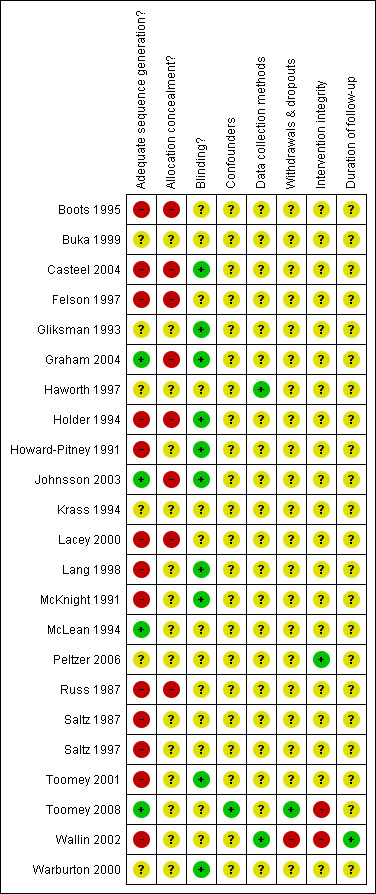

A visual summary of the review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

A summary of the quality of the trials against the quality criteria is presented below. Full details and the risk of bias judgements against each criterion are presented in the risk of bias sections of the Characteristics of included studies.

Allocation bias

In intervention studies, allocation should ideally be random and concealed. Allocation that is not random is likely to lead to unbalanced prognostic factors between the experimental and control groups, which will result in a biased estimate of the intervention effect. Nine studies reported using random allocation but the method used was only described in three of them; drawing lots was used in two (Graham 2004; Johnsson 2003), and a table of random numbers was used in two (McLean 1994; Toomey 2008). In none of the studies was concealment adequate.

One study (Casteel 2004) allocated the bars that agreed to participate in the study to the experimental group and those that refused to the control group. Two studies (Boots 1995; Felson 1997) allocated the intervention to an area previously identified as having a particularly high rate of alcohol‐related problems; regression‐to‐the‐mean should be considered in such instances and is described further in the 'Discussion' section.

Comparability of experimental and control groups at baseline

Baseline differences in alcohol‐related problems and/or average alcohol consumption between the experimental and control groups were reported in three studies (Boots 1995; Casteel 2004; Felson 1997). Ten studies attempted to match participants prior to allocation (Gliksman 1993; Graham 2004; Howard‐Pitney 1991; Krass 1994; Lang 1998; McKnight 1991; Peltzer 2006; Saltz 1987; Saltz 1997; Toomey 2001), although the number and type of factors matched for varied with each study. Two studies reported that the experimental and control groups had similar characteristics (Buka 1999; Lang 1998). One noted the presence of some differences (Wallin 2002). The remaining five studies did not report the presence (or absence) of baseline differences between the groups (Haworth 1997; Holder 1994; Johnsson 2003; McLean 1994; Russ 1987; Toomey 2008; Warburton 2000).

Blinding

To minimise observer bias, outcome assessors should ideally be blinded to the allocation status of participants, as they may be biased towards one group (consciously or not). Blinding of outcome assessment was used in 12 studies that used observers/interviewers to gather outcome data. The randomised controlled trial of toughened glassware (Warburton 2000) also blinded the participants to their own allocation status. Such a double‐blind design is not feasible in the other studies, due to the nature of the interventions under investigation; for example, participants cannot be blind to whether they received training or not.

Injury data (traffic crashes and violence) was collected from official records in four trials.

Data collection method

Methods by which outcome data are collected may be associated with their own biases. For example, self‐reported measures of behaviour are likely to be more prone to bias than observed behaviour.

In the seven studies with a knowledge outcome, six of these measured this in the trained servers only. All trials used a self‐completed test or questionnaire method. Response rates were high in the studies measuring knowledge immediately after the training and were lower in those with a longer follow‐up.

Behaviour was measured in two studies (Boots 1995; Buka 1999) using self‐reported data as the source of outcome data. Response rate to questionnaires tended to be low. Data on behaviour was gathered through observations by investigators in ten studies. Three (Johnsson 2003; Krass 1994; McLean 1994) out of the four studies undertaking patron interviews used a breath test to assess intoxication whilst one (Saltz 1987) collected self‐reported data on alcohol consumption. With the exception of Johnsson 2003, which achieved an extremely high response rate for patron interview (>95%), the remaining studies response rates were lower (range of 40 to 65%). One study (Haworth 1997), in which the intervention was the promotion of the use of publicly available breathalysers, used data from these devices to determine the level of usage.

All but one of the studies gathering injury outcome data used official records as the source, the exception being Warburton 2000 which used a self‐completed questionnaire.

Withdrawals and dropouts

Withdrawals and dropouts need to be minimised in any intervention study. Participants choosing to withdraw from the study are likely to be those with the worst prognosis. It is also important that participants who do not receive or complete their assigned intervention, remain in the analysis (that is, analysis is on an intention‐to‐treat basis).

Seven studies (Boots 1995; Buka 1999; Felson 1997; Holder 1994; Lacey 2000; Saltz 1997; Wallin 2002) allocated the intervention to areas of alcohol serving premises, and received a 'n/a' rating for this criterion. As the design was directed as a geographical area the percentage of participants completing, withdrawing or dropping out is not applicable.

Eight studies (Casteel 2004; Gliksman 1993; Howard‐Pitney 1991; Johnsson 2003; McKnight 1991; Russ 1987; Saltz 1987; Toomey 2008) using individual bar/premises as the unit of allocation, did not report any withdrawals, drop‐outs or loss to follow‐up.

Three studies (Krass 1994; Lang 1998; McLean 1994) reported bars refusing to participate in the patron surveys.

Four studies (Graham 2004; Peltzer 2006; Toomey 2001; Warburton 2000) reported bars withdrawing and/or lost to follow‐up; none of these studies presented outcome data for the affected bars. The information available on one study (Haworth 1997) is unclear as regards withdrawals or drop‐outs.

Intervention integrity and compliance

Eight studies examining server training reported the number of participants trained as a proportion of total servers; three reported training all staff, one trained 84% while the remaining five trained 50 to 60% of staff. In one study (Toomey 2008) 85% of intervention establishments completed their comprehensive training course but only 28% of controls completed the reduced version of the training course that had been planned for them. One of the trials (Holder 1994) was of a mandated training policy, so it is assumed that compliance was high.

Two studies examining health promotion interventions both reported that the extent of compliance with the intervention varied between premises for example, varying from displaying the information to actively distributing it, no further details are reported. The report of the study promoting breathalyser (Haworth 1997) use does not make clear whether promotion activities were completed in all premises.

The Warburton 2000 study involved replacing the bars' whole glassware supply; hence it is assumed compliance was high. The Casteel 2004 study involved making recommendations to managers to implement environmental changes to the bar, again it was reported that compliance was variable.

Follow‐up duration

In the studies assessing the change in knowledge (Boots 1995; Gliksman 1993; Howard‐Pitney 1991; Krass 1994; Lang 1998; McKnight 1991), measurements were made immediately before and after training in two studies, three months after in two, with the remaining three not specifying length of data collection periods in the report.

The timing of post observations of server behaviour to pseudo‐drunk patrons occurred within six months of administration of the intervention, with the exception of one (Wallin 2002), in which observations were made three years after. In the same study (Wallin 2002), post observations of server behaviour to patrons who appeared to be under‐age were made two and five years after. In the study in which use of breathalysers was promoted (Haworth 1997), the duration of follow‐up is unclear.

The timings of the patron interviews/surveys ranged from less than one week to three months after intervention implementation.

The length of data collection periods of injury data in the controlled before‐and‐after studies ranged from nine months to 11 years before and from three months to 15 years after. The Warburton 2000 randomised trial collected injury data for six months after.

Effects of interventions

Due to variability in the intervention types investigated by the included studies, the results have been reviewed qualitatively. The interventions have been grouped into five broad categories; server training, health promotion initiatives, drink driving service, interventions targeting the server setting environment, and policy interventions. With the exception of Graham 2004, studies in the server training category were investigating a sufficiently similar intervention to enable the studies to be presented together, with the results grouped by outcome. The focus of the training in Graham 2004 differed from the others thus has been reported separately. The results of the remaining studies in the other categories have been presented by study due to the variability of the interventions under investigation.

Server training

Fifteen studies investigated the effectiveness of server training; duration of the training interventions ranged from one to two hours to two days. All but one study involved training focusing on the responsible service of alcohol. Common training themes included raising awareness of alcohol service laws, recognition of early signs of alcohol intoxication, and tactics for dealing with intoxicated customers. Five of these reported a specific focus and/or specific training for the managers/owners in responsible alcohol service policies. In Graham 2004, the training was not targeted at responsible service, but on the prevention and management of aggression in bars.

Injury

Full results for the injury outcome are presented in Table 1.

1. Results ‐ server training (injuries).

| Buka 1999 | Not measured. |

| Gliksman 1993 | Not measured. |

| Graham 2004 | Not measured. |

| Holder 1994 | SINGLE VEHICLE NIGHT TIME (SVN) CRASHES Effect estimate = ‐0.524 (95% CI ‐0.956 to ‐0.091), t‐ratio = ‐2.40. The estimate is adjusted for seasonal fluctuations in crashes; alcohol related policy changes (changes to DUI legislation and reduction in legal driving BAL to 0.08) and for pattern of crashes in control states. Authors report the net estimated decline in SVN crashes following the implementation of the policy as: 4% after six months; 11% after 12 months; 18% after 24 months; 23% after 36 months. |

| Howard‐Pitney 1991 | Not measured. |

| Johnsson 2003 | Not measured. |

| Krass 1994 | Not measured. |

| Lang 1998 | Not measured. |

| McKnight 1991 | Not measured. |

| Russ 1987 | Not measured. |

| Saltz 1987 | Not measured. |

| Saltz 1997 | Not measured. |

| Toomey 2001 | Not measured. |

| Toomey 2008 | Not measured |

| Wallin 2003 | POLICE REPORTED VIOLENCE When adjusting for the development in the control area, the intervention parameter = ‐0.344 (se = 0.046), P < 0.001. The authors estimated this to represent a 29% reduction in police‐reported violence in the experimental area. |

Randomised controlled trials

None identified.

Non‐randomised controlled trials

None identified.

Controlled before and after studies

Holder 1994 investigated the impact of a state‐wide mandated server training policy and estimated a continued reduction in the number of single vehicle night time (SVN) crashes; after controlling for drink driving related policy changes and the trend of crashes in the control area, it was estimated that the intervention led to a reduction of 4% after six months, 11% after 12 months, 18% after 24 months, reaching 23% after 36 months.

Patron behaviour

Table 2 Patron behaviour was measured in terms of alcohol consumption in four studies (Johnsson 2003; Krass 1994; Lang 1998; Saltz 1987); three used breath tests to measure BAC, while one (Saltz 1987) used self‐reported alcohol consumption.

2. Results ‐ server training (behaviour).

| Buka 1999 | SELF‐REPORTED SERVER BEHAVIOUR Alcohol serving practices ‐ this was measured in each community using a Desired Server Behaviour Index (DSBI) (score ranged from 1 to 5). The higher the score the more desirable the behaviour. Mean DSBI (+/‐ SD) for overall server behaviour; Experimental community = 3.59 (+/‐ 0.74) Control community A = 3.59 (+/‐ 0.61) Control community B = 3.24 (+/‐ 0.65) Significance test; F=2.96, P=0.06. |

| Gliksman 1993 | OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR TO PSEUDO DRUNKS Measured using a behaviour score based on observations of six scenarios (the higher the score the more desirable the behaviour). (Exact figures are not reported in the report text, but the following estimates were read from a graph). Experimental sites behaviour score increased from ˜15 to 21.5 pre to post intervention. Control sites behaviour score changed from ˜16.5 to 16.4 pre to post intervention. Significance test; F=8.73, P<0.01. |

| Graham 2004 | OBSERVED AGGRESSION EXHIBITIED BY PATRONS (average number of incidents per observation) 1) Consistent rating of severe physical aggression by all raters, definite intent Experimental bars; decreased from 0.053 to 0.035 Control bars; increased from 0.007 to 0.060. Significance test; t= 5.23, df=28, P<0.001. 2) All severe aggression plus consistent rating of moderate physical (with or without verbal aggression), definite intent (average number of incidents per observation) Experimental bars; decreased from 0.134 to 0.101 Control bars; increased from 0.075 to 0.126. Significance test; t= 1.87, df=28, P=0.071. OBSERVED AGGRESSION EXHIBITIED BY STAFF (average number of incidents per observation) 1) Consistent rating of severe physical aggression by all raters, definite intent 'Frequencies too low for analyses. 2) All severe aggression plus consistent rating of moderate physical (with or without verbal aggression), definite intent Experimental bars; increased from 0.029 to 0.056. Control bars; increased from 0.014 to 0.053. Significance test; t= 1.19, df=28, P=0.243. |

| Holder 1994 | Not measured. |

| Howard‐Pitney 1991 | OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR Mean number of interventions made by servers were calculated for eight different responsible interventions, the overall mean for all eight interventions (the higher the mean value the more desirable the server behaviour); Experimental bars = 0.95 Control bars =1.26 Confidence intervals and results of significance test are not presented however, the authors report that 'no differences were observed between treatment and control servers on any intervention or on a sum average of eight possible interventions'. |

| Johnsson 2003 | BEHAVIOUR OF PATRONS Change in BAC(mg%) (and 95% CIs) between baseline and follow‐up; Experimental bars= ‐0.004% (‐0.012 to 0.004) Control bars = +0.007% (‐0.001 to 0.015). Mean difference in BAC between experimental and control bars = ‐0.011% (95% CI 0.022 to 0.000). In the experimental group 40% of tested patrons had a BAC greater than 0.1% before the training and 39% after. In the control group the corresponding figures were 34% before and 41% after. The difference between these changes was not significant (P = 0.12, one‐tailed, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 1.10). |

| Krass 1994 | BEHAVIOUR OF PATRONS 1) Mean BAC (mg%) of patrons This increased from 0.055 (95% CI 0.049 to 0.065) to 0.069 (95% CI 0.058 to 0.078) over the study period in the experimental sites, and increased from 0.057 (95% CI 0.050 to 0.078) to 0.058 (95% CI 0.050 to 0.066). 2) Total consumption of alcohol (gm) On experimental premises this increased from 62.4 (95% CI 50.5 to 74.4) to 69.3 (95% CI 56.9 to 81.6), and decreased from 79.0 (95% CI 82.9 to 95.1) to 67.9 (95% CI 56.7 to 79.1) in control premises. The authors report that 'no significant differences were found in mean BAC and total consumption of alcohol between experimental and control sites at pre and post level'. 3) Proportion of patrons with a BAC over 0.10mg% This increased from ˜0.17% to ˜0.27% in intervention sites and reduced from ˜0.23% to 0.2% in the control sites (exact figures are not presented in the report text, but the following estimates were read from a graph). No confidence intervals or significance test results presented for this outcome. |

| Lang 1998 | BEHAVIOUR OF PATRONS 1) Drink driving offences No quantitative data presented. The authors report that 'the downward trend in drink driving offences from intervention premises leading up to the project was continued during the evaluation period, while the figure for the control sites remained relatively unchanged. However, the number of drink driving cases from both intervention and control premises were too few to permit any meaningful evaluation'. 2) Percentage of tested patrons with a BAL(mg%)> 0.15 This reduced over the study period, with the decline greater for experimental sites (17.4% to 5.3%) than control (10.1 to 3.7%), this is not significant (P=0.389). 3) Percentage of tested patrons with a BAL>0.08 This decreased from 52% to 26.9% in experimental sites and decreased from 34.8% to 24%, this rate of decline is significantly greater (P<0.029) for the experimental than for the control group. SELF‐REPORTED SERVER BEHAVIOUR Changes in the average ratings in mean score of the adoption of responsible service policies over the pre and post periods were reported as not statistically significant (full results of significance test is not presented). Total score increased from ‐0.7 to 0.9 in intervention sites and remained unchanged at ‐1.8 in control sites (maximum possible score=+2, minimum possible score= ‐2). OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR Reported that there was no difference between experimental and control in terms of refusal of service to intoxicated pseudos. In the experimental group, 1 out of 11 visits and 3 out of 14 visits were refused service in the pre and post period respectively. In the control group, 1 out of 14 visits were refused service in both the pre and post period. Authors report that 'no further analyses were undertaken'. |

| McKnight 1991 | SELF‐REPORTED SERVER BEHAVIOUR (trained servers only) 1) Serving practices, mean score (+/‐sd); Pre = 3.13 (+/‐ 0.67) Post = 3.50 (+/‐ 0.68) Significance test; diff=0.57, t=11.90, P<0.01 2) Serving policies mean score (+/‐sd); Pre =0.58 (+/‐ 0.12) Post = 0.65 (+/‐ 0.11) Significance test; diff=0.61, t=6.65, P<0.01 OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR 1) Percentage change between pre and post server 'intervention level': a) Intervention level = 'None' (servers make no attempt to intervene); Experimental = ‐12.5% Control = ‐0.8% b) Intervention level = 'Partial' (servers provide drink requested but make some attempt at intervention); Experimental = +10.5% Control = +1.7% c) Intervention level = 'Full' (servers refuse to serve any alcoholic beverage); Experimental = +1.9% Control = ‐0.7% 2) Mean score of server intervention (the higher the score the more desirable); Mean score in experimental sites increased from 0.19 to 0.34 (diff = 0.15, F=10.42, P<0.01) between the pre and post periods. Mean score in control sites remained at 0.22 (diff = 0.00, F=0.01, P=0.97) between the pre and post periods. Significance test of the difference between the intervention effects in the experimental and control sites; F=6.70, df=1/207, P=0.01). OBSERVED 'REAL' PATRON INTOXICATION Amongst the experimental sites the mean intervention level increased from 0.03 before, to 0.22 after (F=4.27, df=1/127, P=0.04), for the comparison sites remained unchanged at 0.07 (F= 0.87, df=1/167, P=0.35) across the periods. |

| Russ 1987 | OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR Trained servers on average were reported as attempting a greater frequency of intervention than servers without training (P<0.05). BEHAVIOUR OF PATRONS The average exit BAC(%mg) for pseudo patrons served by servers who remained untrained was 0.103 (+/‐ 0.033), while those served by trained personnel had an average BAC of 0.059 (+/‐0.019). The mean difference in exit BACs between pseudopatrons served by trained versus untrained servers = 0.044 (95% CI 0.022 to 0.066). Authors report that the 'BAC levels of pseudopatrons served by trained staff were significantly lower (P<0.01) than those obtained among pseudopatrons prior to training or served by untrained servers in the post period'. |

| Saltz 1987 | BEHAVIOUR OF PATRONS 1) Per capita consumption (number of drinks) Reduced from ˜5.6 to ˜5 in experimental site and ˜6 to ˜5.5 in the comparison site. 2) Rate of consumption (drinks per hour) Reduced from ˜3.5 to ˜2.3 in the experimental site and ˜3.25 to ˜3.75 in the comparison (exact figures are not reported in the report text, but the following estimates were read from a graph). Confidence intervals or results from significance test were not reported. Authors report that 'multivariate linear and logistic regression analyses 'reveal that although absolute consumption and rate of consumption were unaffected by the program, the likelihood of a customers being intoxicated was cut in half'. |

| Saltz 1997 | SELF‐REPORTED SERVER BEHAVIOUR Self‐reported server policy of refusing service to intoxicated patrons (Mean % yes) N. Californian communities Experimental; pre = 3%, post = 19% Control; pre =8%, post = 10% S. Californian communities Experimental; pre 6%, post = 15% Control; pre =6%, post =7% S. Carolina communities Experimental; pre= 7%, post= 8% Control = pre 19%, post 17%. Authors report that 'no statistical difference was found', no further information presented. OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR Pseudo‐patron survey; responsible service assessed using an intervention score (ranging of low [=bad] of ‐2 to +2 [=good]). N. Californian communities Experimental; pre = 0.17, post = 0.21 Control = pre ‐0.15, post = ‐0.19 S. Californian communities Experimental; pre= ‐0.18, post = ‐0.17 Control = pre 0.15, post 0.16 S. Carolina communities Experimental; pre= 0.17, post= 0.07 Control; pre= ‐0.23, post= ‐0.09. Authors report that 'no statistical difference was found', no further information presented. |

| Toomey 2001 | OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR Pseudo‐intoxicated purchase attempts Pre‐intervention, the purchase rates were 68.4% and 70.1%, in the experimental and control sites respectively. Post‐intervention, the purchase rate reduced in the intervention site to 40.0% and increased to 72.9% in the control. The relative decline was reported as not statistically significant (t=‐1.17, P=0.27). Refusal of service to pseudo‐intoxicated patrons changed from 83.1% to 80.3% in experimental and from 63.0% to 54.8% in control (t=0.24, P=0.81). |

| Toomey 2008 | OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR

Pseudo‐intoxicated purchase attempts Total of purchase attempts in all participating establishments that were successful before the intervention and during two post‐intervention follow‐ups. One purchase attempt made in each establishment. Intervention Control Baseline 81/122 (66.4%) 68/109 (62.3%) 1st follow‐up 62 /111(55.9%) 67/105 (63.8%) 2nd follow‐up 73/111 (65.8%) 78/106 (73.58) Authors "observed no significant differences at follow‐up in reported policies/practices across establishments". |

| Wallin 2002 | OBSERVED SERVER BEHAVIOUR 1. Refusal rates to intoxicated patrons (Data in paper published 2003.) 55% in the experimental sites which had received training, 48% in intervention sites yet to be receive training, and 38% in the control area. The authors reported that this was not significant. No further details presented. 2. Successful attempts to buy a drink by patrons who were over 18 but appeared to be under 18. (Data in paper published 2004.) Intervention Control Baseline (1996) 129/307 (42%) 57/146 (39%) 1st follow‐up (1998) 57/146 (39%) 46/106 (43%) 2nd follow‐up (2001) 37/118 (31%) 41/120 (34%) The authors reported that differences between intervention and control groups were not significant. No further details presented |

Randomised controlled trials

In the randomised study by Johnsson 2003 the post‐intervention mean BAC levels were lower in the experimental bars (0.082%) than the control bars (0.087) (MD = ‐0.01 (95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.00). The study authors compared the change in BAC from pre to post intervention for both groups; the mean BAC in the experimental bars reduced to a greater extent than in the control bars, mean difference = ‐0.011% (95% CI 0.022 to 0.000). The odds ratio indicates a modest effect on the percentage of patrons with a BAC > 0.1 (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.26), although this is compatible with the play of chance.

The randomised trial by Krass 1994 reported that a statistically significant difference was not found between experimental and control bars in mean patron BAC or total consumption, with values increasing for both outcomes in both groups. The mean BAC in the post intervention period was 0.069gm% (95% CI 0.058 to 0.078) in the experimental and 0.058gm% (95% CI 0.050 to 0.066) in the control. The percentage of patrons with a BAC > 0.10 in the after period was 27% in the experimental group and 20% the control; no confidence intervals or significance test were reported.

In Peltzer 2006, BAC of patrons was measured but the published data contains errors and omissions and is not usable.

Non‐randomised controlled trials

In the non‐randomised controlled trial by Lang 1998, the change in percentage of patrons with a BAC > 0.15 over the study period declined for both groups (by 12.1% in the experimental, by 6.4% in the control); the reductions were not found to be significantly different (P = 0.389). A positive intervention effect was found for the change in the percentage of patrons with a BAC > 0.08, with the percentage decline significantly greater in experimental bars (‐25.1%) than the control (‐10.8%), P < 0.029. Lang 1998 also measured subsequent drink driving offences, but detected too few offences to evaluate and no data were presented.

Controlled before and after studies

Saltz 1987 compared two Navy clubs, one of which received server training. Self‐reported data indicated no effect on overall alcohol consumption or rate of consumption of alcohol, P > 0.05. However, a positive intervention effect on the risk of having a BAC > 0.10% (as estimated from the number of drinks consumed) was found, P < 0.05.

Server behaviour

Full results for the server behaviour outcome are presented in Table 2.

Randomised controlled trials

Gliksman 1993 used a behaviour score based on observations of six scenarios (the higher the score the more desirable the behaviour). Estimates (read from a graph) showed an increase of score in the experimental sites (+6.5) and a slight decrease (‐0.1) in the control. The difference in score change was found to be statistically significant, P < 0.01.

Peltzer 2006 used a scoring system to assess the behaviour of servers in specific situations. Full details of the system are not included in the published report and only mean values of the total scores for the intervention and control groups are provided.

Toomey 2008 compared rates of successful attempts to be served by pseudo‐drunk patrons in experimental and control sites one and three months after server training had been completed. The study authors report that they found no significant differences at follow‐up in reported policies/practices across establishments.

Non‐randomised controlled trials

McKnight 1991 calculated mean scores of server intervention for each group (the higher the score the more desirable). The score in the experimental sites increased by 0.15 and remained unchanged in the control sites, between the pre and post periods. Significance testing indicated a significant difference, P = 0.01. McKnight 1991 also applied an intervention score to observed server behaviour to 'real' intoxicated patrons; the level increased significantly in the experimental bars (P = 0.04) but not in the control bars (P = 0.35) pre to post intervention.

Howard‐Pitney 1991 calculated the mean number of interventions made by servers for eight different responsible interventions. The overall mean for all eight interventions (the higher the mean value the more desirable the behaviour) was 0.95 for experimental and 1.26 for the control bars. Neither confidence intervals or P values were presented for these estimates; however, the authors reported that 'no differences were observed between treatment and control servers on any intervention or on a sum average of eight possible interventions'.

Saltz 1997 calculated a behaviour score (ranging of low [=bad] of ‐2 to +2 [=good]). In the North Californian communities the score increased by 0.04 in the experimental, and by 0.34 in the control. In the South Californian communities the score increased by 0.01 in the experimental community and by 0.01 in the control. In the South Carolina communities the score reduced by 0.1 in the experimental and increased by 0.14 in the control. The authors report that 'no statistical difference was found', no further information was presented.

The study by Russ 1987 recorded the number of observed responsible interventions made by the servers, and found that the trained servers had a higher frequency of responsible interventions than the untrained servers (P < 0.05). The exit BAC of the pseudo‐patrons was also measured, post‐test only; for the experimental group, average exit BAC = 0.103 (+/‐0.033) and for control = 0.059 (+/‐0.019), this was reported as significant, P < 0.01. Mean difference in the exit BAC of pseudo‐patrons served by experimental versus control servers = 0.044 (95% CI 0.022 to 0.066).

Three studies (Lang 1998; Toomey 2001; Wallin 2002) compared the change in the number of service refusals to pseudo‐intoxicated patrons; neither study found a significant difference between the experimental and control groups.

In Lang 1998 pseudo‐patrons were refused service, in 1/11 and 3/14 visits in the experimental group in the pre and post period, respectively. In the control group, 1/14 visits were refused in both the pre and post intervention period. The authors report that no further analyses were undertaken of this data, due to the small numbers. In the study by Toomey 2001, refusal of service to pseudo‐intoxicated patrons decreased from 83.1 to 80.3% in the experimental and from 63.0 to 54.8% in the control, the difference between the changes was not found to be significant, P = 0.81. Wallin 2002 found that, three years post intervention the refusal rates to pseudo‐intoxicated patrons was 55% in the experimental premises that had received training, 48% in the experimental sites yet to have received training and 38% in the control area. The authors reported that the differences were not significant, but exact results of the significance test were not reported.

The study by Toomey 2001 also measured server behaviour in terms of the number of successful purchase attempts by pseudo‐intoxicated patrons (that is, the lower the number of successful purchases, the more desirable the behaviour). Purchase attempts reduced from 68.4% to 40.0% and increased from 70.1% to 72.9% over the study period in the experimental and control sites, respectively. The relative decline was reported as not being statistically significant, P = 0.81.

Three studies (Buka 1999; Lang 1998; Saltz 1997) measured self‐reported server behaviour, none of which found a statistically significant difference between experimental and control.

Buka 1999 measured self‐reported server behaviour according to a Desired Server Behaviour Index (scale from 1 to 5, the higher the score the more desirable the behaviour) in the experimental and two control communities. Mean DSBI (+/‐SD) was 3.59 (+/‐0.74) in the experimental community, 3.59 (+/‐0.61) and 3.24 (+/‐0.65) in control A and B communities respectively, P = 0.06.

Lang 1998 measured server behaviour by calculation of a score, based on reported adoption of responsible service policies over the pre to post period, each bar was rated against 11 dimensions of responsible service. Average ratings of experimental sites increased in a positive direction for 4/11 dimensions, with the rest unchanged. In the control sites there was one positive, two negative and eight unchanged dimensions in the control sites. The authors report the difference not to be statistically significant but the exact results of significance test were not presented.

Saltz 1997 measured the percentage of premises reporting as having a policy of refusing service to intoxicated patrons. In the North Californian communities the percentage reporting 'yes' increased by 16% in the experimental, and by 2% in the control. In the South Californian communities the score increased by 9% in the experimental community and by 2% in the control. In the South Carolinian communities the score reduced by 1% in the experimental and decreased by 2% in the control. The authors report that 'no statistical difference was found', but no further information was presented.

Controlled before and after studies

None identified.

Knowledge

Full results for the knowledge outcome are presented in Table 3.

3. Results ‐ server training (knowledge).

| Buka 1999 | Not measured. |

| Gliksman 1993 | KNOWLEDGE OF SERVERS This was measured in the trained servers only. Results for the true/false section increased significantly pre to post test, t=‐12.5, P<0.001. Results for the open‐ended question section increased significantly pre to post test, mean score increased from 1.3 to 5.29, t=‐10.89, P<0.001. |

| Graham 2004 | Not measured. |

| Holder 1994 | Not measured. |

| Howard‐Pitney 1991 | KNOWLEDGE OF SERVERS This was measured in trained group only. Formal measures of effect and confidence intervals are not presented however, the authors report that servers and managers increased their knowledge and showed improvement in their beliefs that customers would respond favourably to responsible alcohol service and policies P<0.001, all measures'. |

| Johnsson 2003 | Not measured. |

| Krass 1994 | KNOWLEDGE OF SERVERS This was measured in trained group only. Mean total knowledge score increased from 23.98 to 30.8; t= ‐12.03, df=66, P<0.001. |

| Lang 1998 | KNOWLEDGE OF SERVERS This was measured in trained group only. The authors report a 'statistically significant (>0.05) increase in knowledge of laws regarding serving obviously drunk customers, maintained at follow‐up. Overall, however, there were only minor increases in knowledge, most of which was not retained at follow‐up'. No other quantitative data is reported. |

| McKnight 1991 | Not measured. |

| Russ 1987 | Not measured. |

| Saltz 1987 | Not measured. |

| Saltz 1997 | Not measured. |

| Toomey 2001 | Not measured. |

| Toomey 2008 | Not measured. |

| Wallin 2002 | Not measured. |

Randomised controlled trials

Gliksman 1993 and Krass 1994 reported a statistically significant improvement in knowledge after training (P < 0.05). This outcome was measured in the trained servers only. In Peltzer 2006, while a questionnaire was administered to servers to assess their knowledge and attitude, no data is available in the published report.

Non‐randomised controlled trials

Two studies (Howard‐Pitney 1991; Lang 1998) measured change in knowledge in the trained servers. Both reported a statistically significant improvement in knowledge after training (P < 0.05). This outcome was measured in the trained servers only.

Controlled before and after studies

None identified.

Server training to reduce aggression

The randomised controlled trial by Graham 2004 measured the effect of a 'safer bars' training programme on reducing observed aggression exhibited by patrons and staff, the primary outcome being the average number of incidents of severe or moderate aggression per observation.

A significant positive intervention effect (P < 0.001) was found for severe physical aggression exhibited by patrons (consistent rating by all raters; definite intent); with average number of incidents falling by 0.018 in the experimental and increasing by 0.053 in the control. A positive intervention effect was also observed when examining all severe aggression plus consistent rating of moderate physical (with or without verbal aggression; definite intent), with the average number of incidents decreasing by 0.033 in experimental and increasing by 0.051 in the control over the trial period, however this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.071).

The number of incidents of severe physical aggression exhibited by staff (consistent rating by all raters; definite intent); was too low to enable analysis. Analysis of all severe plus consistent rating of moderate physical (with or without verbal aggression; definite intent), indicated an increase in average number of incidents by 0.027 in the experimental and an increase of 0.039 in the control bars (P = 0.243), over the trial period.

Health promotion initiatives

Full results for the health promotion interventions are presented in Table 4.

4. Results ‐ Health promotion interventions.

| Boots 1993 | |

| Injuries | Not measured. |

| Behaviour | BEHAVIOUR OF PATRONS 1) Self‐reported behaviour of drinkers For the experimental area the authors report that there was 'no significant change in attendance at 'safer' parties (i.e. those that adhered to the tips) between those who had heard of the intervention and others who had not'. a) Provision of food; chi‐squared=2.543, df=3, P=0.4675. b) Provision of alternative drinks; chi‐squared=0.823, df=3, P=0.844. c) Reduction in service to intoxication; chi‐squared=5.844, df=3, P=0.1194. d) Provision of transport; chi‐squared = 4.811, df=3, P=0.1862. In the control area is it reported that there was no significant pre‐post difference, however no quantitative data were reported. |

| Knowledge | DRINKERS' KNOWLEDGE In the experimental area there was no significant community‐wide change in safe partying knowledge resulting from the campaign; chi2=2.254, df=5, P=0.813. No significant pre‐post difference found in the control area, no other quantitative data reported. |

| McLean 1994 | |

| Injuries | Not measured. |

| Behaviour | BEHAVIOUR OF PATRONS 1) Median BAC(mg%) This was 0.030 in both the experimental and control groups (P=0.415). 2) Percentage of patrons with a BAC>0.10 This was 17.5% and 20.0% in the experimental and control groups respectively (P=0.509). 3) Percentage of patrons with a BAC>0.15 This was 7.5% and 7.8% in the experimental and control groups respectively (P=1.000). SELF‐REPORTED ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION 1) This was significantly less in the experimental group (38g) than the control (47g) with P=0.01. 2) Percentage of patrons with a measured BAC>0.05% who intended to drive This was 6.8% in experimental and 7.8% in the control group (P=0.635). |

| Knowledge | Not measured. |

Injury

No studies identified.

Patron behaviour

Randomised controlled trials

One trial was found. McLean 1994 investigated the effectiveness of the distribution and display of sensible drinking information in bars on the alcohol consumption of patrons. No statistically significant difference was found between the control and experimental bars in any of the measures of alcohol consumption used with the exception of the self‐reported data. After the intervention the median BAC(mg%) was 0.030 in both the experimental and control groups (P = 0.415); the percentage of patrons with a BAC > 0.10 was 17.5% and 20.0% in the experimental and control groups, respectively (P = 0.509). The odds ratio for the percentage of patrons with a BAC > 0.1, indicated a modest intervention effect (OR = 0.85, 95% 0.56 to 1.29; n = 18 bars), although this is compatible with the play of chance. The percentage of patrons with a BAC > 0.15 was 7.5% and 7.8% in the experimental and control groups, respectively (P = 1.000); OR = 0.96 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.77). Self‐reported alcohol consumption was significantly less in the experimental group (38g) than the control (47g) with P = 0.01; the percentage of patrons with a BAC > 0.05% who intended to drive was 6.8% in experimental and 7.8% in control group (P = 0.635).

Non‐randomised controlled trials

Boots 1995 investigated the effectiveness of the distribution cards containing 'safe‐partying' tips through liquor stores. Self‐reported data on the behaviour of drinkers were collected. Comparing pre and post intervention responses, no difference was found in the number of drinkers adhering to the tips (providing food, P = 0.4675; providing alternative drinks, P = 0.844; reducing service to intoxication, P = 0.1194; providing alternative transport, P = 0.1862). For the control town, no data is reported, however the authors state that there was no significant pre to post difference. Drinkers' knowledge of the tips promoted by the intervention was only measured in the experimental area; it was reported that there was no significant community‐wide change in safe‐partying knowledge resulting from the campaign, P = 0.813. In Haworth 1997 rates of use of public breathalysers were recorded before and after promotion activities but the published data is not usable.

Controlled before and after studies

None identified.

Drink driving service

Full results for the drink driving service are presented in Table 5.

5. Results ‐ Drink driving prevention services.

| Lacey 2000 | |

| Injuries | ROAD TRAFFIC CRASHES 1) Injury crashes These reduced by 15% in the experimental area after implementation of the programme (t=‐2.61, reported as 'highly significant'), and there was no reduction in the control areas. 2) Fatal road traffic crashes A before‐and‐after analysis of the ratio of the experimental area's fatal crashes to the comparison's fatal crashes, indicated that the ratio reduced from 0.78 to 0.60, this was reported as not being statistically significant (P=0.29). |

| Behaviour | Not measured. |

| Knowledge | Not measured. |

Injury

Randomised controlled trials

None identified.

Non‐randomised controlled trials

None identified.

Controlled before and after studies

Lacey 2000 investigated the effectiveness of a free driving home service for intoxicated drinkers. Injury crashes reduced by 15% in the experimental area after implementation of the programme (t = ‐2.61, reported as 'highly significant'), the authors report that there was no reduction in the control areas. A before‐and‐after analysis of the ratio of the experimental area's fatal crashes to the control's fatal crashes, indicated that the ratio reduced from 0.78 to 0.60, this was reported as not being statistically significant (P = 0.29).

Behaviour

None identified.

Knowledge

None identified.

Interventions targeting the server setting environment

Full results for interventions targeting the server setting environment are presented in Table 6.

6. Results ‐ Interventions targeting the server setting environment.

| Casteel 2004 | |

| Injuries | Post intervention period control versus experimental stores Rate Ratios [adjusted for reported district crime] with 95% CI and P values; 1) Robbery 5.4 (95%CI 0.7‐43) P=0.11 2) Assault 3.4 (95%CI 0.7‐18) P=0.13 3) Shoplifting 5.6 (95%CI 0.9‐36) P=0.07 4) All crime 4.6 (95%CI 1.7‐12) P=0.01 5) Injury 1.1 (95%CI 0.1‐10) P=0.93 6) Police reports 2.7 (95%CI 1.3‐5.4) P=0.01. |

| Behaviour | Not measured. |

| Knowledge | Not measured. |

| Warburton 2000 | |

| Injuries | GLASSWARE RELATED INJURIES INFLICTED TO SERVING STAFF 98 staff experienced 115 injuries; 43 in control and 72 in intervention group. The ratio of number of staff injured in the experimental group to number in the control was 1.72 (95%CI 1.15, 2.59) (˜70% greater risk of injury in experimental group). Relative risk adjusted for people at risk was 1.48 (95%CI 1.02, 2.15). (˜50% greater risk of injury in experimental group). Relative risk adjusted for hours worked was 1.57 (95%CI 1.08, 2.29). (˜60% greater risk of injury in experimental group) P<0.05 (all CIs exclude the null hypothesis). Most injury, 86% and 89% in control and experimental bars respectively, was inflicted to the hands. |

| Behaviour | Not measured. |

| Knowledge | Not measured. |

Injury

Randomised controlled trials

Warburton 2000 was the only included study to be randomised and use an injury outcome. The study compared the effectiveness of two types of drinking glassware; toughened glassware (experimental) and annealed glassware (control) in reducing bar‐staff injuries. The results indicated that the experimental glass caused more injury than the control. Seventy‐two and 43 staff experienced glass injuries in the experimental and control bars, respectively. The ratio of number of staff injured in the experimental group to the number in the control = 1.72 (95% CI 1.15 to 2.59) (˜70% greater risk of injury in experimental group). The relative risk adjusted for people at risk = 1.48 (95% CI 1.02 to 2.15) (˜50% greater risk of injury in experimental group). The relative risk adjusted for hours worked = 1.57 (95% CI 1.08 to 2.29) (˜60% greater risk of injury in experimental group). All P values were < 0.05.

Non‐randomised controlled trials

None identified.

Controlled before and after studies

Casteel 2004 investigated an intervention aimed at reducing crime experienced by the drinking establishment and used a number of injury measures as outcomes, with a statistically significant intervention effect detected for two; all crime and number of police reports. Comparing the control versus experimental stores, the study authors reported rate ratios (RR) (adjusted for reported district crime) and 95% CI and P values; for robbery RR 5.4 (95% CI 0.7 to 43) P = 0.11; for assault RR 3.4 (95% CI 0.7 to 18) P = 0.13; for shoplifting RR 5.6 (95% CI 0.9 to 36) P = 0.07; for all crime RR 4.6 (95% CI 1.7 to 12) P = 0.01; for injury RR 1.1 (95% CI 0.1 to 10) P = 0.93; and for police reports RR 2.7 (95% CI 1.3 to 5.4) P = 0.01.

Behaviour

None identified.

Knowledge

None identified.

Server setting policy intervention

Full results for the policy intervention are presented in Table 7.

7. Results ‐ Server setting management/policy interventions.

| Felson 1997 | |

| Injuries | SERIOUS ASSAULT RATES The study reports that before intervention, the experimental area's serious assault rate was 52% higher than the comparison rate. |

| Knowledge | Not measured. |

| Behaviour | Not measured. |

Injury

Randomised controlled trials

None identified.

Non‐randomised controlled trials

None identified.

Controlled before and after studies

Felson 1997 investigated the impact on serious assault rate, after the introduction of a policy aimed at minimising the movement of drinkers between different bars and their alcohol consumption. The authors reported that before the policy intervention, the serious assault rate in the experimental area was 52% higher than the rate in the control area. After the intervention, the serious assault rate in the experimental area was 37% lower than in the control.

Behaviour

None identified.

Knowledge

None identified.

Discussion

Summary of main results

There is insufficient evidence from high quality intervention studies that interventions in the alcohol server setting are effective in preventing injuries. Only one randomised trial with an injury outcome was identified and this did not detect a beneficial intervention effect. Three randomised controlled trials measured patron alcohol consumption, none of which found a confident estimate of effect. One randomised trial found a statistically significant reduction in observed severe aggression exhibited by patrons. There is conflicting evidence as to whether there is an improvement in server behaviour and the extent to which this might translate into a reduction in injury risk is unknown. Interpretation of this outcome is, therefore, of limited value.

Quality of the evidence

The validity of the inferences based on a systematic review is dependent on the quality of the included studies. Overall, the methodological quality of the studies included in this review was judged to be weak.

Only eight studies used random allocation, and none of these were found to have adequate allocation concealment. Three of these studies used a cluster design and randomly allocated a very small number of clusters (Buka 1999; Gliksman 1993; Krass 1994). The benefits of randomisation are unlikely to be achieved with very small numbers. These studies have been classified as randomised trials in this systematic review however, they are likely to be as susceptible to allocation bias as the non‐randomised trials.

Attempts were made in nine of the non‐randomised designs to minimise confounding through matching of the experimental and control groups, but residual confounding remains a problem.

Ineffective and poorly concealed randomisation in the included studies, means confounding and bias are likely to have influenced the results.

Two studies allocated the intervention to an area previously identified as having a particularly high rate of alcohol‐related problems. With such an approach, regression‐to‐the‐mean should be considered. Regression‐to‐the‐mean describes the tendency for an abnormally high (or low) number of events (e.g. injuries) to return to values closer to the long term mean. Any observed abnormally high (or low) number of events is thus a result of random fluctuation. It is a particular threat to controlled‐before‐and‐after studies and has important implications when the study interest is a change in outcome. In such cases an apparent intervention effect may actually be a result of the number of events returning to the average rate after a random fluctuation. Consequently, these studies should be interpreted with caution.

Blind outcome assessment was widely used in the included studies. It was reported as being used in 11 studies during the collection of behaviour data (important when collecting data on such a subjective outcome). Additionally, the studies measuring injury outcome extracted data from official records (e.g. crash data from government statistics, crime data from police records). When using data from such external, objective sources it is reasonable to assume that outcome assessment is blind.

Questionnaires and interviews were often used to examine behaviour; the response rates were low in a number of studies. This is a source of potential bias as the non‐responders are likely to have the worst prognosis or be at most risk. Such a bias leads to an overestimation of an intervention effect. A number of studies attempted to minimise this bias in the patron interviews, by judging the intoxication level of non‐responders. Similarly, participants who withdraw from the study or are lost to follow‐up are likely to have a poorer prognosis. However, details of such withdrawals and drop‐outs were often not reported; of the few studies that did, it seemed that analysis was not on an intention‐to‐treat basis, nor was outcome data for such non‐participants presented. Cautious interpretation of such studies is needed, as it is likely that their findings over‐estimate any intervention effect.

Intervention compliance was also a problem for many of the studies. In the server training studies, the number of servers actually receiving training in the experimental groups was relatively low, often 50 to 60%. Hence, follow‐up observations of server behaviour had a good chance of being based on a number of untrained servers. In the health promotion studies, compliance was reported as 'variable'. Such a low or variable compliance is a problem for the assessment of intervention efficacy, but does indicate the effectiveness of such interventions, which is arguably of greater interest to public health intervention research.

It is difficult to quantify a sufficient length for a data collection period, but it should be long enough to account for short‐term fluctuations to provide a reliable estimate of outcome. Due to the relatively short length of follow‐up in most studies it is difficult to be confident that a change in outcome is a result of random fluctuation or if any real intervention effect lessens (or increases) over time.

A number of the included studies used a cluster design. A problem posed by cluster data arises from the fact that individuals within a cluster tend to be more similar to each other than to other members of other clusters. Failure to account for this can cause a type of 'unit of analysis error', which results in the P‐values being too small and the confidence intervals too narrow (Wears 2002), and can spuriously overestimate the significance of difference (Alderson 2002). Eight studies reported using appropriate statistical techniques to adjust for this cluster error in their analyses.

Of the variety of interventions that have the potential to be implemented in the server setting, much of the existing literature and intervention research focuses on just one: server training. Such an approach places the emphasis on the supply‐side of alcohol consumption and aims to enable servers to facilitate responsible drinking in their patrons. The approach assumes that an improvement in knowledge leads to an improvement in behaviour, which in turn will reduce the occurrence of injury. However, the appropriateness of this assumption might be questioned; behaviour is a complex concept and subject to multiple influences, knowledge being just one. For example, it is recognised that educational interventions are not effective in reducing alcohol consumption (Hope 2004), hence to assume that such an approach can change the behaviour of servers may be inappropriate.