Abstract

Background: A variety of empirical studies have shown the negative effects of unemployment on health. A research gap exists regarding salutogenic factors and successful coping strategies to master involuntary job loss and unemployment with the least damage to health. Hence, this study aims at generating a deeper understanding of coping with unemployment and maintaining health.

Design and methods: We conducted problem-centered guideline interviews with 21 unemployed people. For the analysis of the interviews, we followed the qualitative content analysis.

Results: The study identified that five themes were particularly relevant in coping with unemployment: i) the financial situation, ii) social support and psychosocial strains due family obligations, iii) health problems, iv) time structure, and v) coping strategies. The respondents expressed their financial situation as a major strain in unemployment. They emphasized the importance of social support by their families, but reported also stressful psychosocial demands due to their family members. Further, our respondents mentioned their health problems as a barrier to reintegration into the labour market. In connection with social role demands, a rudimentary time structure was reported by the participants. The common reported coping strategy in unemployment is seeking social support.

Conclusions: In summary, our results show – besides health problems and a deteriorated financial situation in unemployment – the great importance of social support and time structure for maintaining mental health in unemployment. Consequently, health promotion approaches for the unemployed should especially target social support and time structure.

Significance for public health.

The evidence and theories on the interactions between health and unemployment show that unemployment is a major challenge for public health, especially for prevention and health promotion. In order to be able to design appropriate health interventions for the unemployed, empirical results are needed regarding how people can cope as healthily as possible with this critical phase of life. The significance of the article is that it identifies salutogenic factors and successful coping strategies during unemployment. The results of the study can be used to provide guidance for prevention and health promotion interventions for the unemployed and to inform the unemployed population how to maintain health.

Key words: Unemployment, health, health promotion, coping strategies, coping resources

Introduction

In many countries, the prevailing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic led to a second lockdown of society. Due to the necessary interventions to fight the pandemic, in 2021, a global economic crisis with a growing number of unemployed can be expected.1

In addition to material and economic losses, unemployment has negative effects on health. Meta-analyses have shown that both morbidity2,3 and mortality4,5 is significantly higher among the unemployed than among the employed. Empirical evidence shows that health problems are a relevant barrier for re-employment. 6,7 Particularly long-term unemployment is associated with increased health risks.3 Conversely, health distress decreases upon re-integration into the labour market.3

According to Antonovsky8 a central question in the salutogenic perspective is what keeps people healthy and how can they cope with a critical phase of life like unemployment as healthily as possible? Empirical studies regarding salutogenic factors and successful coping strategies during unemployment are rare.9,10 Research on how to best master the stressful biographical phase of unemployment and prevent damage to health can provide helpful information for work and health promotion, maintaining mental health, and improving the chances of re-integration into the labour market.11-13 In this context, the study by Fryer and Payne14 found that particularly proactive unemployed individuals experienced material but no psychological deprivation. Hence, the present study aims at generating a deeper understanding of the experiences of unemployment; especially of resources and strains, which are important for the coping process in unemployment and about coping strategies that help the unemployed to stay healthy.

Coping with job loss: theoretical and empirical background

There is a consensus that moderating factors influence the individual coping with unemployment, leading to differential health consequences among the unemployed.2,9,13

A frequently discussed moderating factor is the individual financial situation, which is explicitly integrated into theories such as the agency restriction theory15 or the vitamin model by Warr.16 The meta-analysis by McKee-Ryan et al.2 showed a statistically significant association between the deteriorated financial situation due to unemployment and mental health and life satisfaction. Also, the qualitative studies by Giuntooli et al.17 and Hiswåls et al.18 showed that a lack of economic resources has a negative impact on the health of the unemployed.

Besides the financial situation, social support is important for the mental health of the unemployed. Several studies revealed that social support can help mastering unemployment with less damage on mental health.2,11,19,20 The family is often the primary source of social support, but can be a source of psychosocial pressure for the unemployed individual. A variety of studies have shown the ambivalent role families can play concerning the mental health of the unemployed.21

Another often discussed factor influencing the unemployed health is a latent function of employment: time structure. In her deprivation theory, Jahoda22 assumed that the loss of time structure contributes to the psychological impairments in unemployment. Some studies have reported that, compared to the employed, the unemployed have a less structured and expedient time organization. 23 However, the study by Fryer and Payne15 observed that unemployed individuals are also able to structure their time and keep routines. The meta-analysis by McKee-Ryan et al.2 and the study by van Hoye and Lootens24 showed that time structure has a positive coping effect and is associated with better mental health despite unemployment.

The consideration of unemployment as a stressful biographical phase is the basis for stress- theoretical approaches, such as the transactional stress theory of Lazarus.25 The theory emphasizes the importance of coping strategies for mental health. The meta-analysis by McKee-Ryan et al.2 showed that coping strategies in unemployment are correlated with mental health. Job loss coping strategies have most often been conceptualized as either problemfocused or emotion-focused coping strategies.26 Problem-focused coping strategies involve all own actions, which are ideally addressing the cause of the stressor, whereby the person primarily tries to achieve a change of the situation.27 Examples of problemfocused coping in unemployment are actively searching for new job opportunities, participation in training or retraining programs, relocating to another region or improving the financial situation. 2,11,26,28 In contrast, emotion-focused coping aims at improving cognitive and emotional mastery by decreasing the threatening character of the situation.27 Emotion-focused coping strategies include seeking social support, internal distancing, avoidance and repression strategies, distraction, optimism, positive reframing or community activism.2,11,26,28

The present study had two research objectives. One aim of our study is to provide a deeper understanding of resources and strains that influence the coping process in unemployment. The second aim is to identify individual coping strategies which contribute to deal with this stressful biographical phase.

Design and Methods

Sample

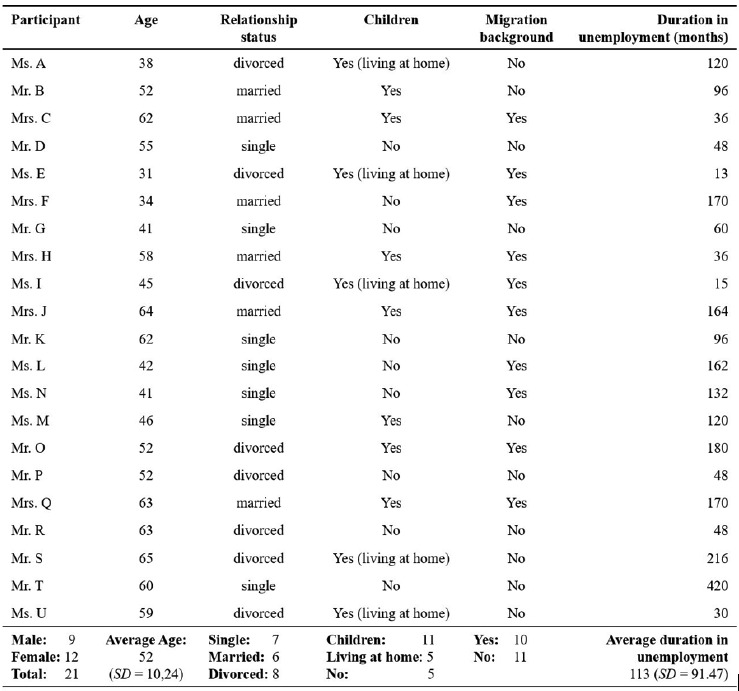

Participants have been recruited in June 2020. The participation criteria were unemployment, defined, according to the German Federal Employment Agency and the Social Code Book II – Basic Social Security for Jobseekers (SGB II), as the absence of gainful employment or being employed for less than fifteen hours per week, and registered unemployed for longer than twelve months. Participation recruitment was initiated by contacting the so-called unemployment centres “Zukunftswerkstatt Düsseldorf” (ZWD) and “Arbeit und Bildung Essen GmbH” (ABEG). We approached the two centres and asked for collaboration in order to reach local unemployed people. Additionally, we directly contacted people, who were taking part in counselling at the ZWD and the ABEG. A total of 21 participants could be recruited for the qualitative interviews. Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of our sample. Pseudonyms are used for the participants.

Informed consent and data collection

Before each of the interviews, all potential participants received all necessary information about the study, the background, the objectives, and how the data would be used in the future. The respondents were informed of their right to withdraw, were assured confidentiality, and were asked to provide written consent. Participation was voluntary following written consent including permission to digitally record the interviews. All interviews were performed face-to-face at the facilities of the unemployment centres ZWD and ABEG and conducted by one interviewer. The duration of the interviews ranged between 20 to 70 min. Data collection took place during June 2020.

To collect the data, individual problem-centred guideline interviews according to Witzel29 were performed. The interviews were based on a structured interview guide, which was developed based on the current literature. The interview guide contained thematic open-ended questions in the domains strains, resources, and coping- strategies.

Data analysis

The audio recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and each transcription was reviewed by the researchers. Data analysis followed the Qualitative Content Analysis according to Mayring.30 In our first step, we defined a potential category system, derived from the current literature. Based on the material, we formulated inductive codes for the categories. Second step was a first run through the whole material with our category system. Combined with this, the current category system was checked for consistency with coded extracts across the dataset and was refined. After this we made a second run through the whole data material with the optimized category system. In this step we collected all sites, from the different analysed transcripts, to the matching categories. Afterwards, the sites from the data were paraphrased and then summarized per category. The last step was the presentation and interpretation in the results. We used MAXQDA Plus 12 (Release 12.3.9) for data analysis. Interview citations were translated from German into English after the analysis.

Results

Financial situation

The participants reported a perceived loss of financial resources after they lost their job and during their current unemployment. In the context of their changed financial situation the respondents described that their basic needs mostly can be covered by the German social security system, but that additional activities, which enable social participation, such as going to restaurants, cafés, cinemas or traveling, must be restricted:

“With three hundred Euros what I am supposed to do? (…) We have to pay rent, we have to pay food and stuff. (…) It feels very bad (...) I want to go to the old town, eat pizza or go shopping, but I can’t.“ (Ms. C)

“Well, of course, I don’t have as much money at my disposal as I did when I was a trainee or in the other jobs. (...) Of course, you have restrictions. I don’t go on holiday or anything like that.” (Mr. G)

“I have the money from the social insurance for unemployment. I live with it, you can actually handle it. (...) Sure, you get upset when you want to go to the cinema. (...) When you see the prices, you think three times about going to the cinema and getting the expensive ticket.” (Mr. R)

From Mr. O’s perspective, his financial situation in unemployment lead to a withdrawal from social relationships, because it is not possible for him to go out with friends:

“You don’t have friends because you can´t go out like the others. (...) If you go out, you are over budget. (...) You should be able to pay for a drink, a coffee, but you can`t.” (Mr. O)

The participants also reported that the lack of financial resources resulted in restrictions in mobility. For example, Mr. B described that he could no longer afford his car, which made it more difficult to visit his sister:

“Visiting my sister or something has become a bit difficult now. (...) I don’t have a car anymore, I just can’t afford it, it’s too expensive for me and she lives a little bit outside the city.” (Mr. B)

In addition, Mr. K, who is diabetic, reported that his existing financial means are not sufficient to buy products for diabetics, which directly can influence his health:

“So the money is a big handicap as a diabetic. With the money I haveI can’t buy products for diabetics.” (Mr. K)

Overall, it became evident in the interviews that the lack of economic resources in unemployment considerably limits the respondents’ scope for action. The financial situation due to unemployment has been described as burdensome and appears as a barrier to social participation.

Social support and psychosocial strains due family obligations

The participants described their family as the main source of social support. Additionally, the respondents also reported social support from their friends and neighbours. Emotional social support was experienced in form of face-to-face conversations or phone calls with family members or friends and helped reducing distress and dealing with application rejections:

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample.

“The job rejections are sometimes hurtful. (...) You then meet with others and then you talk about it. And you talk about this comment and that comment. Sure, no one can do anything about it, but it was said and thereby it helps you.” (Mr. R)

Besides, the interviewees reported also economic and material support, as well as everyday practical help. These helped to reduce financial strains and were seen as a great support in everyday life:

“I live with my parents and have the luxury of being able to eat there. (...) That is support enough for me or, for example, doing laundry. (...) That is actually great support.” (Mr. G)

“We have friends here. They helped us with money and we got along.” (Mrs. H)

Further, the respondents stated that they had received information about vacancies from their friends:

“Actually, always through word of mouth from friends or social welfare office, followed by job center. However, most often, I got jobs through my friends, my network.” (Ms. U)

In addition, the participants reported a helpful exchange of information on health and dealing with authorities by family and friends:

“My wife’s brother, his partner, he is already a physician. Sometimes he tells you what you can somehow still do in terms of health or which offices you can turn to, for example, (…) if you get such rejections from the pension insurance every time.” (Mr. B)

The similarity in the depictions of the interviewees was, that social support was perceived as a special resource in coping with everyday life in unemployment and helped to reduce stress.

However, the interviewees reported that the support they provided for family members, in the form of care, work in the family business, and raising children, were perceived as a burden in unemployment:

“I have been involved in our business all my life. As the son, it´s natural that I work there, (...) but it is also a hugh burden for me. (...) I am more or less the only one who is there for my mother, my grandmother and also for my father and there is also the love too great, I can’t just say “I’m leaving”. I can’t.” (Mr. G)

“After the death of my mother, my father collapsed and I cared for him. (…) Somehow, you don’t have a sense of time anymore. Then it was suddenly 16 years until he died. Shortly afterwards my brother had a stroke. (...) So I do what I can do for him. (...) To be honest, I get tired of it sometimes. I finally want to have some peace and not have to go somewhere every day. (…) I wouldn’t say that I am unemployed, I have more or less a full-time job with the care. (…) That is a mental strain, not only a physical strain.” (Mr. T)

In short, the ambivalent effect of the family on the mental health of the unemployed became apparent. On the one hand, the family was named as an important source of social support, on the other hand, the existing responsibilities and obligations towards family members were perceived as strains by the interviewees.

Health problems as barrier for re-integration into the labour market

The majority of our study participants reported that they suffered from physical and mental health problems. The respondents perceived their existing health problems as a barrier to re-integration into the labour market:

“Why do I think my chances to find a new job are bad? (...) Because I can’t sit for so long. When I sit for a long time, my legs swell up, which can be very unpleasant, and when I walk for a long time, my foot makes problems. That’s why I’m limited by my illnesses.” (Mr. B)

“It’s been clear for a long time that there’s nothing left for me with work. As I said if you’re no longer allowed to do anything with slipped discs. Then I have the prosthesis in my left knee.” (Mr. S)

From the perspective of Ms M., health is a prerequisite for work:

“I keep repeating myself, but at the moment, the most important thing for me is my health. Because without health you can’t get a job.”

Time structure

We observed that most of the interviewees had problems with structuring their day in unemployment. They expressed stressful experiences such as boredom and doing nothing:

“Actually, I get up, drink my coffee, turn on my television (...) and wait until it´s evening and I go to bed.” (Mr. O)

In the case of some respondents, a rudimentary day and time structure became apparent. The leisure time resulting from unemployment was largely filled with personal activities such as household tasks, cooking, gardening and physical activities:

“So my day is clocked. (…) Always the same! Get up, have breakfast, housework. I keep myself fit by running. (…) I cook. It also takes time if you really cook everything fresh. Yes, I am already busy for two hours (...) and I have a small balcony garden that I take care of every day. (…) I am pondering, but in fact, I have no idle time. (…) For my psyche, the things I do are very imminent because they give me something.” (Ms. N)

In addition, a rudimentary day structure was reported when children were raised or family members were supported and cared for:

“I always get up early in the morning. Rhythm always has to be there ... (...) I have to do at home all the time some work. (...) So I am now twice on call. As I said, I am on call for our company and I share the care of my grandmother’s with my mother. (…) These activities mean a lot to me, of course, because this is my family.” (Mr. G)

In fact, of an existing time structure, the interviewees assigned their daily activities have a high sense of purpose for themselves.

Coping-Strategies in unemployment

The respondents stated seeking social support as primarily coping strategy to deal with the stressful biographical phase of unemployment:

“I asked my parents and they helped me a bit, not with money, but with food or clothes or something. (...). Now I’m coping well with my finances.” (Ms. L)

“A friend of mine is a lawyer, and if I have something, I call him and he tells me what I should do. Free of charge! As a best man“ (Mr. P)

As further coping-strategy, the interviewees reported that they searched for professional services and sought them out or were using the services at the time of the interviews, which reduced psychosocial stress:

“For a while there was a lot of pressure, also from home, that was a bit to much. Then I went to a social counselling centre. (…) I could talk with the consultant there about all kinds of things. Just talk a bit off the top of my head. That was actually pretty good for myself.” (Mr. G)

“Well, now I’ve had so much stress that I couldn’t handle it on my own. Then I went to a psychologist for treatment. (...) That´s a great help for me.” (Ms. M)

Some respondents were characterized by a high level of proactivity, which enables time structure and social relationships:

“My day starts at 5:30 am, when there is a small breakfast and I have to take medication. (…) Around nine o’clock, I am leaving the apartment, going for a walk, shopping, doing everything in the morning until noon. You have to organize the whole afternoon for yourself, you always have something to do. (…) For example, today at noon I will record a church service from a local community, where I’m also in, where the flag team is also in.” (Mr. D)

As mentioned in the previous chapter, the interviewees also reported doing household tasks, physical activities and gardening as strategies to structure their day and to fill the available leisure time in unemployment. In addition, the respondents described that physical activities and gardening as well serve to distract from stress and problems:

“The best way to clear your mind is to go for a walk. (…) Sometimes you think „Wow, this all sucks“ and (...) when you do something in the garden (...) or go swimming, it’s like „You’ve done something“. That feels pretty good.” (Mr. R).

The interviewees also reported cultural activities, like “listening to music” and “reading”, and creative activities, like “crocheting”, “embroidery” and “knitting”, as distancing and relaxing strategies:

“I have these wireless headphones. Then I sit down, and listen to music (...) even if it’s only the ‘Magic Flute’. That is already relaxing for me and helps me to switch off a bit. (…) My relaxation is crocheting and knitting, it helps me a lot to relax. Or I read a book, (...) this is pure relaxation for me because it is even more exciting than anything else.” (Ms. U)

For a better emotional coping with unemployment the participants also mentioned optimism, accepting the situation and external attributions:

“So if I sit here and think all the time „I’m in a shitty situation“, then the first stomach ulcer comes, then the next one and so on. That doesn’t work. You have to deal with the situation in a positive way.” (Mr. G)

“My personal solution is: „Accept it! Live with it!“ and that’s what I do. All kind of under cover. Just live. I don’t know what tomorrow is, but I have to live today. That’s my solution.” (Mr. O)

“I’m not the only unemployed person in Germany. That’s what I think. (…) I can’t do something if companies go bankrupt, if companies no longer hire people. That’s the system.” (Mr. R)

In summary, the different reported strategies helped the participants to cope with the stressful biographical period of unemployment. In connection with these strategies, it was often reported that psychosocial strains and distress were reduced.

Discussion

The present study focuses on the resources and strains our participant’s experiences in unemployment and the coping strategies the participants use to master the stressful biographical phase of unemployment.

Resources and strains

For coping with unemployment our interviews stated that social relationships are of great importance for them. Through family and friends, social support in form of emotional, instrumental and informational support was experienced. The received social support helped to manage distress, to cope with experiences of failure, to reduce financial hardships, as well as to deal with authorities and find a job. That social support is a health-promoting resource in unemployment has been empirically shown.2,11,19,20 Beyond previous research findings, the results of our study show that all forms of social support are used and can contribute to cope with psychosocial strains in unemployment.

On the other side, our results also indicate that the obligations towards family members can be a strain for the unemployed person. Especially the care of family members was described as a physical and as a psychological strain. The ambivalent character of the family for the mental health of the unemployed is also demonstrated by the current state of research.21 Previous research has constantly shown that the financial situation in unemployment is a strain for the individuals. For instance, former qualitative studies observed that the lack of economic resources in unemployment limit the possibility of social participation, whereby the financial situation was perceived as a source of major stress and so had a negative impact on health.17,18 These results are in line with our analysis. We also identified that participation in social activities, such as traveling, going to the cinema as well as to restaurants or cafés with friends, have to be restricted due to the loss of financial resources. Hence, these activities can only be pursued to a limited extent our respondents experienced their financial situation as a strain. In the present study it was observed that several participants had problems with structuring their day, which led to stressful experiences such as boredom and idleness. This has also been reported in previous studies.23 In contrast, other interviewees described a rudimentary day and time structure in unemployment. In relation to an existing time structure, participants indicated that the activities they perform have a high sense of meaning for themselves. Studies have shown that unemployed individuals who are doing meaningful leisure activities have better mental health.31,32 In accordance with previous studies we found that there is a connection between social role demands and time structure.24,33 Based on our results and the studies mentioned above, daily routines and time structure in unemployment seem to be related to social role demands. A new result in this context is, that the role as caregiver contributed to feelings of not being unemployed.

Our participants mentioned, that they suffer from different health problems; which are always a strain for individuals. In line with the current state of research, our respondents experienced their health problems as a barrier to re-integration into the labour market.7, 6 Hence, health problems can be the reason for a prolonged phase of unemployment and can lead to long-term unemployment. Particularly, long-term unemployment is a psychosocial strain and has a negative effect on health.3

Coping-strategies

Our participants described a number of different coping strategies to manage unemployment. The majority of the interviewees expressed that they were seeking support from their family and friends. As described above, social support is of particular importance in coping with unemployment and has a positive effect on mental health. Hence, seeking for social support can be seen as a helpful coping strategy in unemployment.

Beyond the findings in previous qualitative studies, our participants also mentioned seeking for formal support. The professional services helped them to reduce psychosocial strains and to maintain mental health. Therefore, the strategy seeking professional help and use these services can be considered as a successful coping activity in unemployment. In our study, the participants described gardening and physical activities as strategies to prevent boredom and to distract from problems and stress. Hence, both activities can be seen as helpful strategies to maintain mental health in unemployment. The positive health effects of gardening and physical activities have been empirically demonstrated in studies outside of unemployment research.34,35 In the context of the requirement for independent structuring the day, our respondents reported doing household tasks. Although this helped to structure daily life, previous research has shown that that there is no effect on mental health by physical activity in the context of household tasks.35 A small proportion of our participants reported a proactive behaviour to cope with unemployment, by filling their day with activities that were highly meaningful to them. The interviewees who were proactive not only experienced the significant latent function of employment – time structure – they also experienced social contact. These results are in line with the study by Fryer and Payne.14 Based on their results and our own results proactively coping with unemployment seems to be particularly purposeful, as it contributes to time structure and social relations. Some of our participants reported cultural and creative activities, as distraction and relaxation strategies. In former qualitative studies in unemployment research, these activities have not been reported as coping strategies. However, previous studies that did not specifically focus on unemployment have shown health-promoting effects for cultural36,37 and creative activities.38 In addition, our results show that the participants use optimism for a better emotional coping with unemployment. Meta-analytically, it has shown that optimism is a successful coping strategy in unemployment and has positive effects on health.2

Limitations

The study only included two municipalities and a small number of participants; thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. Participation in the survey was voluntary. Regarding our sample, it must be mentioned that the group of up to 30 years could not be reached and interviewed by us. By researching this group other individual resources and strains, as well as coping strategies in unemployment, might have been identified. Future studies should especially focus on this group. Additionally, women are over-represented in our sample, which does not correspond to the distribution in the unemployed population in Germany.

Conclusions and implications

Our participants perceived their social relationships, especially their families, as an important coping resource. Moreover, according to the interviews, the primary coping strategy is searching for social support. The social support our participants received was helpful for the job search and to reduce mental health problems. The survey also showed the relevance of time structure for mental health. Social role demands and proactive behaviour contributed to maintaining daily structure in unemployment. According to the study results, another helpful coping strategy is seeking professional services. Future studies should investigate in the interaction effects. Our results have implications for health promotion for the unemployed. Social support and time structure are special resources in unemployment and contribute to the promotion of mental health. Hence, unemployed people should be informed by the respective unemployment services and during interventions about the importance of time structure and social support for coping with unemployment. Concerning time structure, this study’s findings revealed that it seems important to identify together with the unemployed person individual activities with sense of purpose which contribute to structuring their day because our participants reported different activities to use their leisure time in unemployment. In addition, the unemployed should be supported in independently accessing professional support services. This coping strategy proved to be particularly helpful in reducing psychosocial stress for some of our interviewees. This is a great challenge, especially in times of the Corona pandemic with rising unemployment figures and declining social contacts due to lockdowns.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the unemployment centers in Düsseldorf and Essen for helping with the recruitment of the study participants. In addition, the authors thank all respondents for their participation in the study.

Funding Statement

Funding: Funding for this trial is provided by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant number: BMBF/DLR FKZ: 01EL2001).

References

- 1.International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: A long and difficult ascent. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund; 2020. Accessed: 2021 Jan 15. Available from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/09/30/world-economic-outlook-october-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKee-Ryan FM, Song Z, Wanberg CR, Kinicki AJ. Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: a meta-analytic study. J Appl Psychol 2005;90:53–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul KI, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J Vocat Behav 2009;74:264–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milner A, Page A, LaMontagne AD. Cause and effect in studies on unemployment, mental health and suicide: a meta-analytic and conceptual review. Psychol Med 2014;44:909–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roelfs DJ, Shor E, Davidson KW, Schwartz JE. Losing life and livelihood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:840–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virtanen P, Janlert U, Hammarström A. Health status and health behaviour as predictors of the occurrence of unemployment and prolonged unemployment. Public Health 2013;127:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollederer A, Voigtländer S. [Die Gesundheit von Arbeitslosen und die Effekte auf die Arbeitsmarktintegration].[Article in German]. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2016;59:652–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonovsky A. A somewhat personal odyssey in studying the stress process. Stress Med 1990;6:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollederer A. Unemployment, health and moderating factors: the need for targeted health promotion. J Public Health 2015;23:319–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janlert U, Hammarström A. Which theory is best? Explanatory models of the relationship between unemployment and health. BMC Public Health 2009;9:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blustein DL, Kozan S, Connors-Kellgren A. Unemployment and underemployment: A narrative analysis about loss. Vocat Behav 2013;82:256–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollederer A. Health promotion and prevention among the unemployed: a systematic review. Health Promot Intl 2019;34:1078–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul KI, Hassel A, Moser K. Individual consequences of job loss and unemployment. In: Klehe U-C, van Hooft EAJ, editors. The Oxford handbook of job loss and job search. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fryer D, Payne R. Proactive behaviour in unemployment: findings and implications. Leisure Studies 1984;3:273–95. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fryer D. Employment deprivation and personal agency during unemployment: A critical discussion of Jahoda's explanation of the psychological effects of unemployment. Soc Behav 1986;1:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warr PB. Work, unemployment and mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giuntoli G, Hughes S, Karban K, South J. Towards a middlerange theory of mental health and well-being effects of employment transitions: Findings from a qualitative study on unemployment during the 2009-2010 economic recession. Health (London) 2015;19:389–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiswåls A-S, Marttila A, Mälstam E, Macassa G. Experiences of unemployment and well-being after job loss during economic recession: Results of a qualitative study in east central Sweden. J Public Health Res 2017;6:995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milner A, Krnjacki L, Butterworth P, LaMontagne AD. The role of social support in protecting mental health when employed and unemployed: A longitudinal fixed-effects analysis using 12 annual waves of the HILDA cohort. Soc Sci Med 2016;153:20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huffman AH, Culbertson SS, Wayment HA, Irving LH. Resource replacement and psychological well-being during unemployment: The role of family support. J Vocat Behav 2015;89:74–82 [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKee-Ryan FM, Maitoza R. Job Loss, unemployment, and families. In: Klehe U-C, van Hooft EAJ, editors. The Oxford handbook of job loss and job search. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. p. 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jahoda M. Work, employment, and unemployment: Values, theories, and approaches in social research. Am Psychol 1981;36:184–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creed PA, Bartrum D. Explanations for deteriorating wellbeing in unemployed people: Specific unemployment theories and beyond. In: Kieselbach T, Winefield AH, Boyd C, Anderson S, editors. Unemployment and Health: International and Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Bowen Hills: Australian Academic Press; 2006. p. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Hoye G, Lootens H. Coping with unemployment: Personality, role demands, and time structure. J Vocat Behav 2013;82:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazarus RS. Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGrawHill; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanisch KA. Job loss and unemployment research from 1994 to 1998: A review and recommendations for research and intervention. J Vocat Behav 1999;55:188–220. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solove E, Fisher GG, Kraiger K. Coping with job loss and reemployment: A two-wave study. J Bus Psychol 2015;30:529–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witzel A, Reiter H. The problem-centred interview. London: SAGE Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedure and software solution; 2014. Available from: URL: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ball M, Orford J. Meaningful patterns of activity amongst the long-term inner city unemployed: a qualitative study. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 2002;12:377–96. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waters LE, Moore KA. Reducing latent deprivation during unemployment: The role of meaningful leisure activity. J Occup Organ Psych 2002;75:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jahoda M, Lazarsfeld PF, Zeisel H. Marienthal: The sociography of an unemployed community. New York: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soga M, Gaston KJ, Yamaura Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Prev Med Rep 2017;5:92–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White RL, Babic MJ, Parker PD, et al. Domain-specific physical activity and mental health: A meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:653–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linnemann A, Strahler J, Nater UM. The stress-reducing effect of music listening varies depending on the social context. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016;72:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bavishi A, Slade MD, Levy BR. A chapter a day: Association of book reading with longevity. Soc Sci Med 2016;164:44–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaimal G, Ray K, Muniz J. Reduction of cortisol levels and participants' responses following art making. Art Ther (Alex) 2016;33:74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]